COVID-19 PCR: home-testing experience of blind and partially sighted people

A user experience evaluation conducted by the PCR Home Test Service in collaboration with the Royal National Institute of Blind People, the Macular Society, Visionary and the Thomas Pocklington Trust.

The PCR Home Test Service (HTS) was first rolled out for key workers in April 2020 and expanded to the wider population by May 2020. As part of the UK NHS Test and Trace programme, HTS was launched as a means of improving accessibility by capturing those who were unable to get to a test site, were shielding or self-isolating, had mobility issues, lived in rural areas or had physical or mental impairments.

Home PCR test process

The process for carrying out a home PCR test was as follows:

- Order a PCR test kit online or call 119 (0300 303 2713 in Scotland).

- Read instructions before opening the test kit.

- Locate a priority post box or use courier collection (assistance via 119, NHS Scotland helpline).

- Register PCR test kit to obtain results (you will need a 10 digit order ID plus 11 character test kit barcode plus 13 character barcode on the prepaid label).

- Ensure kit components are present and undamaged.

- Wash hands then perform swab of throat and nostril, insert swab into the plastic tube.

- Insert sample tube into zip-lock bag then insert this bag into biohazard bag.

- Assemble the returns box, insert biohazard bag and apply security seal.

- Return the test sample via the returns route identified previously.

- Receive result via email and text or call 119 (NHS Scotland helpline).

NHS Test and Trace strives to deliver services that are accessible to all users. A one-size-fits-all approach cannot be adopted as different groups within the population may require responses more tailored to their specific needs. HTS was quickly recognised as being a suitable alternative to in person testing for people who are blind and partially sighted (BPS).

According to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), figures from 2017 show there are approximately 350,000 people registered as blind and partially sighted in the UK. However, even this cannot be considered a homogeneous group of individuals as they display a wide variation in visual abilities and circumstances which can be influenced by the severity of sight loss and age of onset, to name but a few. Furthermore, these numbers only reflect those who have been in some contact with health and social care services and as such, there may be more than 2 million people currently experiencing some form of sight loss.

Home self-testing is not straightforward for BPS people, particularly if they live alone. In order to continually monitor and improve the service offered by NHS Test and Trace, 2 user experience evaluations were undertaken in collaboration with voluntary sector partners in May 2020 and in February 2021 respectively. The first aimed to understand the end-to-end experience for BPS participants, from ordering a test kit to receiving a result, and to identify the range and depth of challenges to home testing. The second sought feedback from BPS participants on some bespoke assistance incorporated in response to the first evaluation. This report describes the 2 evaluations, summarises their findings and describes how services have been adapted to support service BPS users.

User experience evaluation I

In the first evaluation, the RNIB helped to recruit 29 BPS people using their established communication routes. The ease with which these individuals were able to access and complete home PCR testing through the live service was then monitored. Participants agreed to researchers observing them by video throughout the process. Researchers did not intervene or offer advice to participants at any stage of the process so as not to undermine the holistic experience of the service. Individuals could use whatever visual aids were normally available to them, including help from a sighted individual, assistive technology or devices. Additional feedback was garnered by interviews conducted by the research team. Participants partaking in the evaluation all stated that they were asymptomatic for coronavirus (COVID-19) so that anyone unable to complete and return the test would not be at a disadvantage clinically.

The group comprised:

- 23 individuals who were severely sight impaired since birth or for more than 20 years

- 4 who had developed a severe impairment within the last 20 years

- 2 individuals who had experienced partial sight loss from birth or for more than 20 years

Evaluation I feedback

BPS people want to complete the test independently without having to rely on friends and family. People expect the call centre to be able to assist with a broad range of issues across the user journey. Feedback provided at different stages of the process are highlighted below.

Before the test

The GOV.UK platform is in general well suited to serve most BPS people.

However, finding and reading barcode numbers for registration and courier pickup was almost impossible for participants to complete without assistance.

Preparing for the test

Digital text only instructions would be preferred by most BPS participants.

The flow of the instruction document should support people in preparing for the test.

Instructions should describe the objects by their tactile qualities as well as provide enough information to understand the purpose of each object.

Taking the test

Accidental contamination of the test kit was the main concern for participants.

Identification of some kit components was challenging without assistance.

The swab test was considered unpleasant but intuitive for participants to carry out

Packaging the test

Complex manual activities like sealing the biohazard bag and especially folding the box were very hard to complete for most of the participants.

For returning the test, participants liked having the option to choose between the post box and courier pick up.

After the test

Arranging courier collection was difficult or impossible for most participants to do unaided because it required them to be able to read the number on the Royal Mail label, therefore returning the sample through a postbox was the only viable option.

Participants didn’t have a strong preference between receiving the results by text or by email.

Additional feedback from participants

Concerns were raised regarding possible accessibility issues for BPS people who are less confident with using, or do not use technology.

Difficulties reading barcode numbers generated the highest risk for BPS people not to engage with the test

Going back and forth between different platforms, browsers or devices, and navigating between apps such as SeeingAI and the registration portal, proved very difficult.

User experience evaluation II

User engagement identified a series of issues which impacted accessibility and from this work, improvements were identified. HTS sought to redress accessibility issues and proposed modifications underwent a second round of evaluations. The introduction of a new support service for this BPS user group would also be examined.

The scope for evaluation was as follows:

- A trial of a live video assistance service with trained support specialists from the 119-call agent population, using the Be My Eyes smartphone app. This supported participants to carry out the end-to-end home testing process via a free, live one-way video call.

- A trial of improvements to the packaging design of the returns box. Participants either received an easier to assemble flatpack design or a preassembled box.

- An online portal on GOV.UK providing alternative formats of home testing instructions including HTML text only, Easy Read and accessible PDF formats.

- Improved instructions with enhanced descriptions for a sample of participants who were testing the redesigned flatpack returns box.

- Improvements to general accessibility and usability of online services.

NHS Test and Trace continued its association with RNIB but the partnership was now expanded to include the Macular Society, Visionary and the Thomas Pocklington Trust. The role of the voluntary sector partners again proved invaluable in a number of areas. They were part of the delivery team and contributed to decision-making in determining the research approach and delivery of the study. In addition, they led a training session for 119 call agents ahead of the trial of the live video assistance service regarding best practice for communicating with people with sight loss. The voluntary sector partners appraised the guidance document and the script used by these 119 agents, as well as contributing to the trial Be My Eyes app content.

As before, communications raising awareness of this evaluation were distributed by the voluntary sector partners through various channels. Ninety-eight BPS participants were enrolled by dedicated NHS Test and Trace team members:

- 72% of participants classed themselves as being severely sight impaired or blind

- 43% stated their eye condition had been present from birth

- a further 24% had been affected for most of their lives

Overview of participants

The following gives background information on the makeup of the participants (for a graphic representation of this data see Figure 1, below).

Registered as blind and partially sighted

Yes, severely sight impaired or blind – 72%

Yes, sight impaired or partially sighted – 18%

Yes (unspecified) – 9%

No – 1%

Proportion of life with an eye condition

From birth – 43%

Most of my life – 24%

Recently or within last few years – 14%

Around half my life – 10%

Less than half my life – 9%

Cause of eye condition

Retinitis pigmentosa – 75%

Diabetic retinopathy – 8%

Glaucoma – 7%

Cataracts – 5%

Age-related macular degeneration – 3%

Other – 2%

Gender

Female – 56%

Male – 44%

Ethnic group

White – 93%

Asian or Asian British – 4%

Black, African, British or Caribbean – 2%

Another ethnic group – 1%

Devices and internet use

“I’m comfortable using the internet completely independently” – 43%

“I can use the internet to do most things independently” – 42%

“I can use the internet with support from someone else” – 11%

“I don’t use the internet or someone else always uses the internet for me” – 3%

Figure 1. Overview of participants

There was a generational divide in the use of technology, with younger BPS people much more likely to be using the internet, a computer or a smartphone, compared to older people. It has been reported that less than one in 3 BPS people feel able to make the most of new technology. Although some non-digital means were used, most of the recruitment for this study was organised via social media and other digital channels, indicating some degree of digital literacy was prevalent amongst the participants. As such, 85% of the study group described themselves as being comfortable using the internet completely independently or were able to use the internet to do most things independently. All participants were made aware of the specialist support available through live video assistance as part of the enrolment process. Once again, participants were able to use whatever visual aids were normally available to them.

Evaluation II outline

Participants were placed into 2 groups to examine different aspects of the service.

The first group was asked to confirm and expand on the original insights. There were 10 participants, each was interviewed for one to 1.5 hours for their feedback on a range of topics including digital exclusion.

The second group was asked to provide feedback on their experience of the improvements. This group was further split by the different approaches used to gather feedback:

In Group 2A, there were 10 participants who were interviewed about their experience of ordering a home test kit. They were then observed whilst they used the test kit and were interviewed afterwards to describe their experience. This group was provided access to the trial Be My Eyes service so that their organic, unprompted use of this support could be understood. Observation and interview sessions lasted from one to 2 hours.

In Group 2B, 9 participants were observed as they ordered and subsequently used the home test kit; they were interviewed after each observation to describe their experience of each step of the process; this group was provided with access to the trial Be My Eyes service, and they were actively encouraged to try and critique it at each stage of the process. Each observation and interview session lasted one to 2 hours.

In Group 2C, 69 participants were asked to complete the end-to-end home testing process without being observed and were then asked to complete a survey to provide feedback about their experience of the process as a whole. This group was provided with access to the trial Be My Eyes service so that their organic, unprompted use of this support could be understood.

Feedback was also provided from the specialist team of 119 call centre agents, who provided the trial live video assistance service via the Be My Eyes app.

Half of the participants from each group (2A, 2B and 2C) were sent a pre-assembled returns box to use. The other half from each group received a redesigned, easier-to-assemble flatpack design. The participants from group 2C who received the flatpack box were also emailed an additional set of instructions which had been produced by the RNIB. These included more haptic, tactile descriptors throughout, and feedback was sought to assess if they were suitable for wider use.

Evaluation II feedback

The sections below highlight the experience of participants as well as identify areas where the service could be improved.

Live video assistance via Be My Eyes

Half of the participants made use of the trial Be My Eyes service, and their experience regarding the quality of assistance provided was overwhelmingly positive. Many felt they wouldn’t have been able to complete the home test without assistance via Be My Eyes. Having someone patiently provide step-by-step verbal guidance throughout the process helped provide participants with reassurance and reduce their anxiety. Using Be My Eyes allowed the 119-call agents to address any challenges experienced by individual users, offering a more tailored support service which wouldn’t otherwise have been possible.

Participants reported that live video assistance was especially helpful for kit registration, with the agents being able to locate and read the test kit barcodes on their behalf, as well as discussing their local postal options and talking them through how to assemble the returns packaging. Participants in the second evaluation also provided feedback on how a live video assistance service should be more widely communicated among people with sight loss. For example, emphasis should be given to the fact that the 119 call agents providing assistance are actually specially trained NHS Test and Trace staff, and not the volunteers who are generally associated with Be My Eyes.

Participants advised that potential users should be informed that the support offered can be flexible depending on their requirements, for example, support can be provided throughout the whole home testing process, or just to assist at specific, smaller key stages such as barcode reading. Live video assistance call agents can arrange courier bookings and also provide clear guidance on postage timings and wider context for test results.

Be My eyes was routinely available as part of the Home PCR Test Service to all who required it.

Improved flatpack returns box

Although some participants were able to assemble the flatpack box with support via live video assistance, it often took longer than participants and advisers thought it should take, required repeated instructions to achieve assembly and was sometimes the cause of frustration. There was also uncertainty from participants as to whether their attempts to self-assemble boxes were robust enough to protect the sample during shipping. Attaching the security seal often proved problematic due to difficulties removing it from its backing. Furthermore, the security seal sometimes got lost when opening the kit package, or it was misidentified as a small piece of paper or part of the test kit delivery packaging because of its texture.

There was general agreement from participants that a pre-assembled returns box or another simpler packaging design would be more usable for shipping samples.

Home PCR tests now contain an easier-to-assemble flatpack box.

GOV.UK portals and guidance pages

Following feedback from Evaluation I, alternative formats of PCR home test instructions were available on GOV.UK. Having a wide choice of formats was important to satisfy individual preferences and needs. Formats that were highlighted by participants as being most useful included:

- audio only and video instructions with audio description

- PDF and text only (HTML)

- hard copy large or giant print booklet

- digital and hard copy braille

- Easy Read

This feedback supports the continued provision of a variety of formats, both digital and hard copy. Participants provided general feedback regarding the navigation and ease of use of the GOV.UK portals, including the compatibility and usability of the ordering and registration portals when using assistive technology, such as screen readers. Participants also provided feedback regarding where they would expect to find support services, including alternative formats of instructions, signposted across the digital journey.

Those with sight loss without digital access

Throughout the duration of these trial periods, further modifications were added to the service, which proved beneficial to this community and the public at large. Those who are unable or have no access to digital platforms including email, internet or mobile phones can access PCR testing via the 119 service.

Pain point mapping – taking the test

The following describes the response rates from the 69 participants in group 2C to each step of the testing process. The percentage of users who found a step challenging is shown in brackets. Under each step are given some personal responses expressed by group members. This data is conveyed in graphic form in Figure 2.

Before the test

Opening the home test kit (17% of users found this step challenging)

“No obvious tear point. I was concerned opening the kit through brute force might damage something.”

Identifying the parts of the kit (20% of users found this step challenging)

“I was concerned about making sure I got everything right and did not want to feel items and contaminate them despite washing my hands as instructed.”

“After having read the enhanced instructions carefully a number of times, I was able to identify each piece of the kit without help.”

Prepare for the test

Using the instructions (45% of users found this step challenging)

“I found it rather confusing as I did not have instructions in a format I could read.”

“The instruction booklet was not accessible. The font size was too small, the contrast of colours was very poor.”

Registering the kit (55% of users found this step challenging)

“Several long codes which are not easily accessible for someone with little or no vision.”

“Spent more time doing the kit than actually doing the test.”

“I was put off by how complicated the initial opening and registration processes seemed.”

Choosing how to send the sample back (23% of users found this step challenging)

“Maybe a pro tip which is concentrated on reassuring you that it is perfectly OK to utilise the [courier] collection service if it would be in any way difficult for you to get a specialised post box.”

Take the test

Collecting the swab with the sample (42% of users found this step challenging)

“Something is needed to make the swab easier to feel through the wrapper – the difference between the 2 ends is very slight and the risk of getting hold of the wrong end is very high.”

“Making it more obvious where to snap off the stick.”

Putting the swab into the tube (32% of users found this step challenging)

“The tube is quite narrow and it would be easy to miss the opening and accidentally touch your hand or the side of the tube hence contaminating the sample.”

Sealing the plastic bag (17% of users found this step challenging)

“I wouldn’t have realised the absorbent pad was part of the kit, I thought it was just a bit of packaging.”

“For those with little or no sight at all, this yellow strip coud be made to feel more tactile.” (The yellow strip to seal the plastic bag.)

Package the test

Packaging the sample (41% of users found this step challenging)

“It was like doing a jigsaw with no instructions and no picture – that’s what it’s like for blind or partially sighted people doing the test.”

Attaching the label (22% of users found this step challenging)

“Replace the origami box with a different kind of return packaging that does not need to be built.”

“Label needs a ‘peel easy’ section that can be felt (that’s to say, is obvious) as I struggled to take it off the backing (which I could barely distinguish as the edging was so small).”

After the test

Sending back the sample (14% of users found this step challenging)

“If I’m not ill it would be easy.”

Pain point mapping: taking a test

Figure 2. Responses from group 2C highlighting challenging steps

User feedback and engagement

Although these evaluations of user experience were small in scale, they were important in identifying possible barriers to home PCR testing within the BPS community. Feedback gained from these studies, as well as from other sources, has been used to implement service improvement.

The customer feedback survey and the Be My Eyes management dashboard are regularly reviewed to identify further opportunities for continuous improvement, both to the home PCR testing route but also to other services within home testing and across all of NHS Test and Trace where relevant.

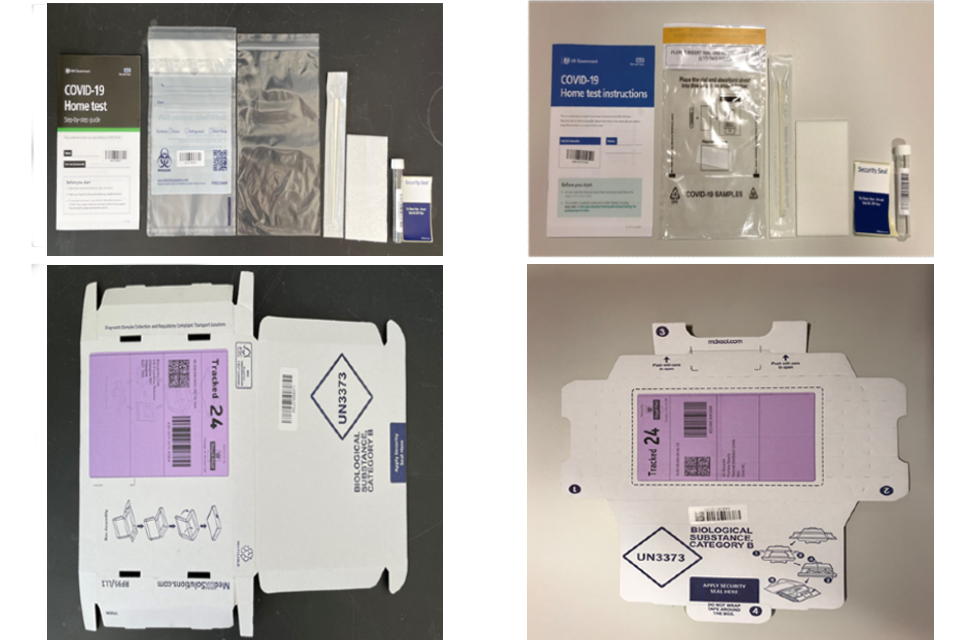

Figure 3 shows images of the contents for kits issued as part of the first evaluation and kits available for BPS individuals as of summer 2021. Table 1 lists the components for these kits.

Figure 3. Image of Home PCR test kits, summer 2020 (left) and July 2021 (right)

Table 1. Table listing components of PCR test kits, then and now

| Home PCR test kit summer 2020 | Home PCR test kit July 2021 |

|---|---|

| 24-page printed instruction booklet | 12-page printed instruction booklet. Also available in alternative formats (both digital and hard copy). Formats include: easy read, large and giant print, Braille, audio, and 12 different translations of the easy read instructions for non-English speakers |

| Flatpack box requiring customer assembly | Easier-to-assemble flatpack box |

| Biohazard bag | Single leakproof bag |

| Zip-lock bag | |

| Swab | Swab |

| Plastic tube containing liquid | Plastic tube containing liquid |

| Security seal to close the box | Security seal to close the box |

| Absorbent pad | Absorbent pad |

Overall, the voluntary sector partners have welcomed the service modifications as likely to improve accessibility and the experience for the community they represent. The Home Test Service, as well as the programme more broadly, continues to work in close collaboration with these and other voluntary sector partners, seeking out their expert opinion to help us identify and drive service improvements.

Authors

Gary Paterson PhD, Public Health and Clinical Oversight, UKHSA

Amy Freer, Service Improvement Lead for Home Testing Channel, UKHSA

Heather Simpson, Accessibility Policy Lead, UKHSA

Jamie McCain, Inclusive Design Lead, UKHSA

Sarah Tunkel MBBS MRCOG, Public Health and Clinical Oversight, UKHSA

Tom Fowler PhD FFPH, Public Health and Clinical Oversight, UKHSA

Main contact

Heather Simpson: [email protected]