Consolidation of defined benefit pension schemes

Updated 17 July 2023

ISBN: 978-1-78659-116-6

Introduction

1. This consultation seeks views on a number of measures to support the consolidation of defined benefit (DB) pension schemes. In particular, we are seeking views on a new legislative framework for authorising and regulating DB ‘superfund’ consolidation vehicles of the type envisaged by the white paper Protecting defined benefit pension schemes, published in March 2018.

2. Many in the pensions industry believe that superfund consolidation represents a potentially more efficient way of managing legacy DB pensions for some closed schemes. While we welcome innovation, we recognise that these vehicles have a different risk profile to that seen in traditional DB pension schemes and therefore pose their own set of challenges. There is broad consensus around the need for a new legislative and regulatory regime to ensure superfunds operate as intended, including a requirement for all superfunds to be authorised. The aims of the superfund authorisation and regulatory regime will be that:

- members of superfunds benefit from equally effective protections to members of other DB pension schemes

- the risks specific to superfunds are proactively regulated – risks include the replacement of the employer covenant by external capital, potential commercial interests within the superfund, and other factors that influence their financial resilience and viability

- The Pensions Regulator (TPR) has the right tools and powers to intervene when necessary

3. These proposals have been developed in close consultation with TPR, the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) and other stakeholders.

4. This document also includes an update on work to introduce an accreditation regime for new and existing DB master trusts and changes to guaranteed minimum pensions (GMPs) conversion legislation.

About this consultation

Who this consultation is aimed at

We expect this consultation to be primarily of interest to:

- employers who sponsor a DB pension scheme(s)

- trustees

- those seeking to establish a superfund

- members of a DB pension scheme(s)

- pension professionals

- life insurers

Purpose of the consultation

This consultation sets out our proposals for how a future legislative framework for authorising and regulating superfunds might work. The consultation document contains a number of questions about specific aspects of the policy. In developing our proposals we have looked to other authorisation and regulatory regimes such as those for defined contribution (DC) master trusts and Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) authorised firms.

We would particularly welcome views on whether our proposals offer sufficient protections for members, including views on our proposals around the financial sustainability and governance arrangements of superfunds discussed in Chapter 3, and the introduction of a regulatory gateway for schemes looking to enter a superfund, discussed in Chapter 5.

Scope of consultation

This consultation applies to England, Wales and Scotland. It is envisaged that Northern Ireland will make corresponding regulations.

Duration of the consultation

The consultation period begins on 7 December 2018 and runs until 1 February 2019.

How to respond to this consultation

Send your consultation responses to:

Defined Benefit team

Private Pensions and Arm’s Length Bodies

1st Floor, Caxton House

Tothill Street

London

SW1H 9NA

Email: [email protected]

Government response

We will aim to publish the government response to the consultation on GOV.UK. Where consultation is linked to a statutory instrument responses should be published before or at the same time as the instrument is laid.

The report will summarise the responses and outline our next steps.

How we consult

Consultation principles

This consultation is being conducted in line with the revised Cabinet Office consultation principles published in March 2018. These principles give clear guidance to government departments on conducting consultations.

Feedback on the consultation process

We value your feedback on how well we consult. If you have any comments about the consultation process (as opposed to the issues which are the subject of the consultation), or if you feel that the consultation does not adhere to the values expressed in the consultation principles or that the process could be improved, write to:

DWP Consultation Coordinator

Legislative Strategy team

4th Floor, Caxton House

Tothill Street

London

SW1H 9NA

Email: [email protected]

Freedom of Information (FoI)

The information you send us may need to be passed to colleagues within the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), published in a summary of responses received and referred to in the published consultation report.

All information contained in your response, including personal information, may be subject to publication or disclosure if requested under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. By providing personal information for the purposes of the public consultation exercise, it is understood that you consent to its disclosure and publication. If this is not the case, you should limit or remove any personal information. If you want the information in your response to the consultation to be kept confidential, you should explain why as part of your response, although we cannot guarantee to do this.

To find out more about the general principles of FoI and how it is applied within DWP, contact the Central FoI team: [email protected].

The Central FoI team cannot advise on specific consultation exercises, only on FoI issues.

Read more about the Freedom of Information Act.

1. Background

1. As we set out in the white paper Protecting defined benefit pension schemes, the available evidence shows that the DB sector is working well and that the vast majority of members are likely to get their benefits paid in full. However, we also identified areas where the system could be improved and made more efficient, including through the consolidation of individual pension schemes.

2. Consolidation already happens across the pensions market to varying degrees, from sharing and outsourcing administrative services, to pooling assets and liabilities through common vehicles such as DB master trusts, to insurance buy-ins and buy-outs. Whether and how schemes choose existing consolidation options will depend on their own specific circumstances.

3. A significant proportion of schemes remain in deficit, and have done over the last decade, despite £120 billion being paid in special contributions, the majority of which were deficit reduction contributions. While the outlook for the vast majority of schemes is positive, in that members can expect to receive the pensions they have been promised, there are some schemes where the outlook is much more uncertain. In some cases, a closed DB pension scheme can be a significant burden for the sponsoring employer, limiting their ability to focus on their core business, including investment for the future and the pay and pensions of current employees. In these circumstances pension scheme members can be exposed to a significant insolvency risk of the sponsoring employer.

4. Encouraging a well regulated superfund sector may offer a more effective way of managing liabilities for some schemes. It would provide an incentive for employers to inject significant sums into their schemes to bring them up to being sufficiently well funded on a prudent basis, so that they can enter a superfund. This potentially significant up-front investment would allow the employer to discharge their legacy liabilities, and concentrate on their core business, while being reassured that the members of their pension scheme are likely to be better protected in the long term.

5. For suitable DB schemes, factors which should improve the probability of benefits being paid in full in a superfund include:

- the injection of additional funds from the employer or its parent group

- the capital buffer provided by a superfund’s investors

- the efficiencies of scale offered by a consolidation vehicle

- the absence of potential future sponsoring employer insolvency

6. Superfunds will have the benefits of scale. They are likely to be able to access a wider and potentially more innovative mix of investment opportunities. Provided the right regulatory regime is in place to deter excessive risk taking, the interests of members and investors are likely to be more evenly balanced. Both stand to benefit from a well regulated regime. In addition, the ability of superfunds to deploy significant capital in the investment markets is also likely to be of benefit to the wider economy as trustees will look to have a well-diversified portfolio which might include investment in later-stage venture capital, or growth-capital for small-medium enterprises. This is also discussed in more detail in the recent HM Treasury policy paper Financing growth in innovative firms: one year on.

7. Trustees will decide whether to transfer a scheme into a superfund, subject to the eligibility conditions which may be imposed by regulation. Before agreeing to the transfer they will need to see evidence that members’ benefits are better protected in the superfund than they would be remaining in the sponsoring employer’s scheme. Trustees will also be required to notify TPR at the earliest opportunity of the intention to transfer to a superfund. The extent of the role of TPR in the transfer of a scheme to a superfund is an issue raised in this consultation. This subject is discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

8. We envisage that superfunds will be classed as a type of DB occupational pension scheme, with the employer covenant replaced by a capital buffer provided by investors. However, we accept that the risk profile of superfunds differs from that of traditional DB occupational pension schemes with a sponsoring employer. As such, as well as the existing DB occupational pensions legislative and regulatory framework, additional safeguards will be needed. These should ensure that members’ benefits and the PPF are properly protected and a sensible and sustainable balance is struck between the interests of members, the sponsoring employer, and the superfund investors.

9. This consultation seeks views on an appropriate legislative framework for the authorisation and regulation of superfunds looking to enter the market.

10. Many of our proposals would require primary legislation and we will seek to legislate in due course when parliamentary time allows. In the meantime, we would expect any superfund considering entering the market to engage with TPR and the PPF before doing so. We would also expect employers considering a transfer of their DB scheme into a superfund to seek voluntary clearance from TPR before any transfer takes place.

2. Regulating superfunds

11. In the UK, the idea of superfunds started to enter wider public discourse in 2017. Since publication of the white paper, we have seen a number of different superfund models preparing to enter the DB market. The Pensions and Lifetime Saving Association (PLSA) has supported enabling superfund consolidation, and the PLSA DB Taskforce published a number of reports between March 2016 and September 2017 which included their view of the required regulatory regime and the potential benefits that could be gained from superfund consolidation.

12. We consider that the current legislative framework does not prevent a superfund setting up and attempting to attract other funds to consolidate. However, there are clear risks in doing so without a suitable regulatory framework to ensure member protection. Government therefore has 3 options:

- do nothing and rely on TPR to manage the emerging superfunds with their current powers

- legislate to prevent superfund consolidation

- legislate for an effective regulatory regime so that members, employers, regulators and the wider economy benefit from the potential offered by superfund consolidation

13. This government has chosen the third option to embrace innovation, and to proceed with what is a difficult but potentially worthwhile program to enable a properly regulated superfund consolidation sector.

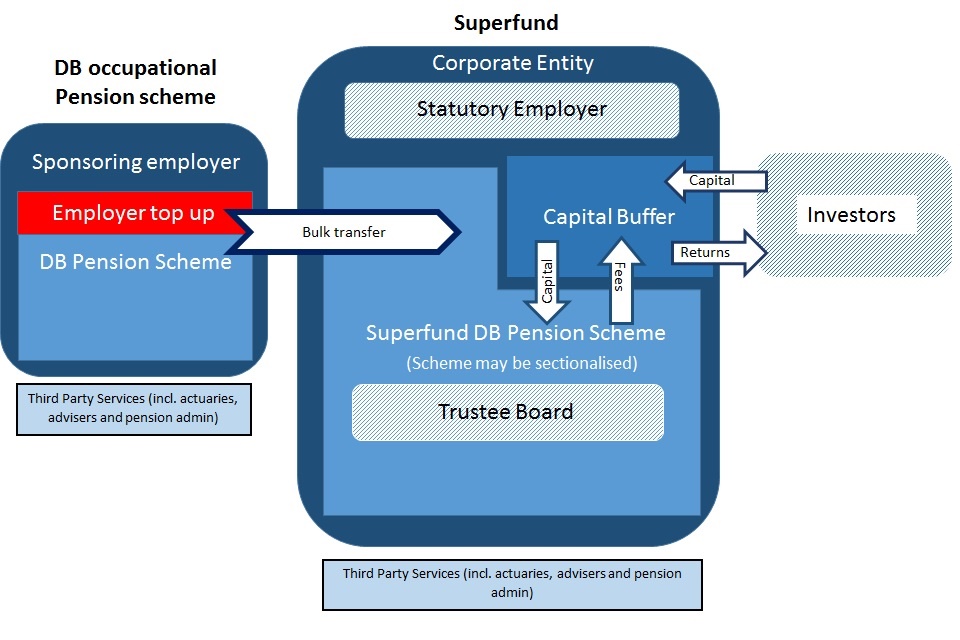

14. Diagram 1 sets out a very simplified structure of a potential superfund and should be viewed in this context. There will of course be variations between the complexities of superfund structures depending on their business models.

15. A basic superfund structure includes:

- a corporate entity

- a statutory employer

- a DB pension scheme

- a capital buffer

- potentially, in-house service providers (for example pension administrators)

16. The capital buffer is furnished by capital provided by external investors (who expect a return) and/or the fee paid by ceding employers for entry to the superfund. The capital buffer may be managed entirely separately to the superfund pension scheme’s assets. The structure for the buffer will be subject to approval as part of the authorisation process. The corporate entity is responsible for the overall management of the superfund, with trustees responsible for the management of the superfund’s pension scheme. The corporate entity would also be the statutory employer in respect of the DB occupational pension scheme. The pension liabilities from the ceding scheme will be transferred to the superfund through the existing bulk transfer process.

Diagram 1

17. We envisage that a scheme within a superfund will continue to be classed as an occupational pension scheme, with the employer covenant replaced by a capital buffer provided by investors as well as potentially the ceding employers, and will be subject to the legislation and regulation appropriate to occupational pension schemes.

18. Superfunds have some similarities to insurance, given that the traditional employer link is broken, and the protection for members’ benefits in the long term is provided by a capital buffer. The corporate entity will become the statutory employer in the superfund; however, the ‘employer covenant’ will only extend to the limit of the capital buffer. Superfunds will not be required to provide the same level of confidence that benefits will be paid in full as an insurer following a buy-out of the scheme liabilities. We envisage that schemes within the superfund will be trust based occupational pension schemes, with trustees expected to act in the best interests of all the members to minimise the risk that members will not receive their pensions in full. The superfunds’ governance arrangements should ensure trustees’ freedom to act in this manner is not impinged upon.

19. A strong regulatory framework for superfunds will be needed to ensure that there are appropriate protections for members and that the risk of regulatory arbitrage with the insurance buy-out market is minimised. Without an effective gateway (discussed in Chapter 5) superfunds would enjoy a considerable competitive advantage in the price of acquiring DB schemes compared to insurers given the lower capital requirements in the occupational pension space.

20. In addition, it is important that the regulatory framework for superfunds operates in such a way as to preserve the integrity of the current regulatory framework for insurers. Insurers are regulated under Solvency II which is a comparatively stringent regulatory regime compared to the regime for DB pension schemes. There may be a need to guard against incentives for insurance companies to establish a vehicle outside the current regulatory structures to acquire, or conduct, business that would otherwise have been acquired by the insurance company itself which could weaken the current regulatory framework for insurers.

21. A consequence of regulating superfunds in respect of DB occupational pension schemes rather than as an insurance arrangement is the minimum compensation that would be available to members on the failure of the superfund. As a DB occupational pension scheme, members would be eligible for PPF protection and not compensation under the Financial Services Compensation Scheme. The latter provides different benefits from the PPF.

22. We entirely accept that superfunds are not exactly the same as traditional DB occupational pension schemes with sponsoring employers and that they pose different risks. These include:

- the fact there is no enforceable recourse to the former employer, corporate entity, or investors for the trustees to get further financial support once the capital buffer has been exhausted

- the commercial element of the emerging superfund propositions and the expectation of investors to make reasonable profits from the capital which they put at risk alongside the assets of the scheme

- the concentration risk which arises from consolidating the variety of employer covenant and investment strategy risks from multiple schemes into the risk of a single investment strategy failing – given the potential size of superfunds, the consequences of their investment strategy failing could have significant impacts for scheme members and the PPF levy payers

23. We are therefore consulting on a more robust bespoke regulatory framework for these consolidation vehicles.

Defining superfunds

24. Superfunds differ from more traditional ways of managing DB liabilities in some respects. We think that these differences would be an appropriate place to start in defining superfunds for the purposes of any future regulatory regime. Based on extensive and ongoing consultation with the industry and those designing the emerging models we have seen, our initial view is that the main characteristics of a superfund are that:

- a superfund is, or contains, an occupational pension scheme set up for the purposes of effecting consolidation of DB pension schemes’ liabilities

- a transferring scheme’s link to a ceding employer is severed on transfer to the superfund

- the ‘covenant’ is a capital buffer provided through external investment that sits within the superfund structure

- there is a mechanism to enable returns to be payable to persons other than members or service providers

25. We want to ensure that the definition captures current and future vehicles that are appropriate to the new targeted regime, and excludes any arrangements that are not intended to be superfunds or are already effectively regulated within the existing regime. In addition, we want to avoid unintended consequences, such as inappropriately constraining the scope of the industry to innovate in designing new consolidation vehicles. We would welcome views on whether these characteristics are the right ones to define the types of arrangement to which the new regime will apply and whether there are any other characteristics which could help in defining superfunds.

Question 1

Are these characteristics wide enough to define a superfund? If not, how could superfunds be defined for the purposes of a future regulatory regime?

Question 2

Given the differences of superfunds and traditional DB occupational pension schemes, what are the additional risks and challenges associated with TPR regulating superfunds?

3. Authorisation

26. Given both the range of emerging business models and the potential scale of superfunds, there is broad consensus for the need for an authorisation regime. The authorisation regime we are proposing, will assess whether a superfund:

- has a viable business model

- is financially sustainable

- is well governed

- has a high probability of being able to pay members’ benefits as they fall due

27. We propose that a superfund will be required to seek authorisation from TPR in order to operate and will be prohibited from operating as a superfund unless it is authorised. To cover TPR authorisation costs, we propose introducing an application fee. We consider ongoing levies in Chapter 4. From the outset, the onus will firmly be on the corporate entity and trustees of the pension scheme of a superfund to demonstrate and evidence how the superfund meets and continues to meet the authorisation criteria.

28. Under the proposal, TPR would be required to either grant or refuse authorisation within a set period of time. Should authorisation be refused, TPR will be required to set out the reasons for its decision and the corporate entity of the superfund will have the right to appeal to the Upper Tribunal.

Authorisation criteria

29. In order to be authorised, TPR will have to be satisfied that the superfund meets certain criteria. The criteria we propose are that the superfund:

- can be effectively supervised

- is run by fit and proper persons

- has effective administration, governance and investment arrangements

- is financially sustainable

- has contingency plans in place to protect members

30. We believe that these criteria meet the aims of the authorisation regime set out at the beginning of this chapter and are consistent with other authorisation regimes, in pensions and broader financial services such as that for DC master trusts and PRA regulated firms.

Question 3

Are the proposed authorisation criteria the right ones for the superfund regulatory regime?

31. The authorisation regime will cover the entire superfund structure, that is both the corporate entity and the scheme. We are aware that some superfunds may wish to establish their scheme on a sectionalised basis. Where this is the case, we do not propose that each section be treated as a separate scheme for the purposes of authorisation. While the funding for these schemes may be sectionalised, the authorisation criteria go wider than this and require a view across the entity as a whole. Sectionalised schemes are discussed further at paragraphs 143 and 144.

Question 4

Are there any circumstances in which it would be advantageous, or necessary, that the authorisation criteria are not applied to the whole superfund but instead to individual segregated sections when the superfund scheme is sectionalised?

Supervisability

32. The structure of superfunds has the potential to be extremely complex. It will be important that TPR can effectively supervise superfunds to protect members and the PPF. To ensure that superfunds can be effectively supervised, we think it will be necessary to set some clear limits on the types of corporate structures that are appropriate.

33. We propose that the corporate entity of a superfund should be established as a body corporate incorporated in the United Kingdom (UK) with their head office and their registered office maintained in the UK. Any companies controlled by the superfund would also be required to be incorporated in the UK. We note that it has been suggested that some superfunds intend to use the Scottish Limited Partnership structure. UK insurance companies are not allowed to be partnerships and we would welcome views on whether there should be a similar restriction placed on superfunds.

34. In order to grant authorisation, TPR would also need to be satisfied that it can effectively supervise a superfund. In particular we would expect TPR to take into account the way the superfund is organised, consider close links with other persons and assess whether membership of a corporate group could hinder supervision.

35. Taken together, we believe that these requirements will promote transparency and ensure that superfunds are established with corporate structures which are compatible with close regulatory supervision, while still maintaining the market’s ability to innovate.

Question 5

Are these restrictions the right ones to ensure that superfund corporate structures are transparent and compatible with regulatory supervision? Are there any other measures that would aid TPR’s ability to supervise superfunds?

Question 6

Should the corporate entities of superfunds be permitted to be established as partnerships or should they be required to be set up as a UK limited company?

Fit and proper persons

36. A number of authorisation regimes include a fit and proper persons requirement to assess whether individuals are suitable to conduct regulated activities. In general, this test seeks to ensure that individuals act with honesty, integrity and propriety and that they are competent (either on an individual or collective basis) to carry out their responsibilities. We propose that a similar requirement be applied to superfunds.

37. The fit and proper persons requirement for superfunds will need to capture those whose actions have the potential to impact member outcomes. This includes not only those within the superfund (both the corporate entity and the scheme), but also those who are in a position to exert influence over entities within the superfund.

38. Identifying individuals who are subject to the fit and proper persons requirement will be based on the nature of their responsibilities within and in relation to the superfund. This is consistent with other authorisation regimes and provides more flexibility than basing the requirement on job titles or roles.

39. We have set out some suggested responsibilities that could be subject to a mandatory fit and proper persons requirement. In addition, we propose that TPR should have discretion to request evidence that other specified individuals meet this requirement where they could exert influence and/or can impact member outcomes. This would not necessarily be restricted to individuals within the superfund structure. For example, TPR might reasonably want to assess whether individuals within a superfund’s parent group or those providing a significant amount of external investment are fit and proper persons.

Question 7

Should TPR have a discretionary power to require evidence that individuals outside the superfund structure meet the fit and proper persons requirement?

40. It will be important for TPR to be able to properly identify those individuals who should be subject to the fit and proper persons requirement. We therefore propose that both the corporate entity and the pension scheme be required to clearly set out their governance arrangements on application, including the role of any committees and sub-committees. We propose that this would be supported by a statement of responsibilities, completed by those subject to the fit and proper persons requirement, which would outline their responsibilities and how their role fits within the wider superfund structure. The intention behind this statement would be to provide TPR with a clear picture of how the superfund is governed and enable them to identify gaps within the governance structure.

Question 8

Would these requirements be sufficient to allow TPR to identify those subject to a mandatory fit and proper persons requirement?

41. We would also welcome views on whether it would be appropriate for TPR to have the ability to interview individuals as part of the fit and proper process. Both the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and PRA have a similar power as part of Senior Managers/Insurance Managers Regime. The purpose of the interview would be to gather additional information to complete the assessment of an applicant’s fitness and propriety to perform their role. The interview could cover any aspect of the fit and proper requirements but we would expect most to focus on whether individuals understand and are able to explain their roles and regulatory responsibilities within the superfund. Interviews could also explore how an individual’s knowledge or experience equips them to carry out the role. The decision to interview would be at TPR’s discretion; however we would expect them to adopt a risk based approach based on, for example, the size, complexity and risk profile of the superfund.

Question 9

Should TPR have the power to interview individuals for the purposes of the fit and proper test?

42. The fit and proper persons test will be an ongoing requirement supported by the significant events framework discussed in Chapter 4. Under this framework, superfunds would be required to inform TPR prior to changing personnel subject to the mandatory fit and proper persons requirement.

Roles within the superfund subject to a mandatory fit and proper persons requirement

43. We list below the areas which in our view should be subject to a mandatory fit and proper persons requirement. We believe that these areas are key to the effective operation of the superfund, in particular that:

- it is adequately funded and financially sustainable

- it is well governed

- compliance, investment and operational risks are well managed

- it is well resourced

- members’ interests are protected

44. We would expect superfunds to have arrangements in place to cover the responsibilities listed below. Note that a ‘person’ could mean an individual or a corporate entity. Where a person is a corporate entity, the same standards would apply and we propose that all relevant directors and senior managers would be subject to the fit and proper persons requirement. We propose that the mandatory fit and proper persons requirements are applied to a person:

- who establishes a superfund

- responsible for the overall management and conduct of the superfund (for example, CEO)

- responsible for the overall management and conduct of the superfund’s non-executive board

- responsible for the overall management of financial resources (for example, CFO)

- responsible for the overall management of risk (for example, CRO)

- responsible for investment decisions and/or implementation for the pension fund or capital buffer (for example, CIO)

- responsible for overall management of internal audit and compliance

- who can appoint trustees

- who can alter trust deeds

- who is a trustee

Question 10

Are there other areas that should be included as part of the mandatory fit and proper persons requirement?

The fit and proper persons test

45. The authorisation regime for DC master trusts introduced a fit and proper persons requirement as a criteria for authorisation, which will be monitored through ongoing supervision and the significant events detailed in Chapter 4, which consists of 3 tests. These are:

- the integrity test

- the conduct requirement

- the competency test

46. These tests are consistent with other fit and proper persons regimes, including FCA rules for financial institutions and financial advisers. We do not propose introducing any additional tests for superfunds as we believe these tests would meet the aim of the fit and proper persons requirement in assessing whether a person acts with honesty, integrity and propriety and that they are competent to carry out their responsibilities. In addition, we believe using similar tests to DC master trusts would provide consistency and reaffirm our expectations to industry. We therefore propose to introduce these tests for the purposes of superfund regulation.

The integrity test

47. An integrity test is generally used to assess a person’s tendency to be honest, trustworthy, and dependable. We propose to set out a number of matters which TPR must take into account when assessing honesty and integrity. These could include, but are not limited to, bankruptcy, unspent criminal records and any previous contravention of TPR rules or rules of any other regulatory authority.

The conduct requirement

48. We propose that the conduct requirement would allow TPR to take into account the actions and behaviour of those subject to the fit and proper persons requirement when assessing whether they act with honesty, integrity and propriety. It could cover past behaviour as well as being an ongoing requirement as part of supervision. The conduct requirement could take into account, for example, whether a person is under investigation or disciplinary action by a regulator, government agency or professional body, whether they have been dismissed or forced to resign in a related area and how open and honest they have been in providing TPR with information.

Extending standards to the corporate board

49. Trustees have a fiduciary duty to act prudently, responsibly, honestly, and impartially in the best interests of members. Given that superfunds will not have a historic link to members transferring into the fund, we would welcome views on whether similar requirements should be placed on individuals on the board of superfund’s corporate entity. In particular, we would welcome views on whether we should introduce standards of conduct, with which such individuals would have to comply. The purpose of such standards would be to ensure high standards of corporate behaviour and to increase the accountability of the corporate board. In particular, we would envisage the standards covering:

- the culture of the corporate board

- interaction with TPR and other regulators

- treatment of members

50. Any future standards could be included as part of a Code of Practice for superfunds discussed in Chapter 4.

Question 11

Would introducing a set of standards of conduct for the superfund’s corporate board be proportionate?

Question 12

What in your view should form the basis of any standards of conduct?

The competency test

51. We propose that the competency test would aim to assess whether a person identified as being subject to the mandatory fit and proper persons requirement has the right skills, knowledge and experience to carry out their role. In assessing competence, TPR could take into account for example relevant professional experience, membership of professional bodies as well as professional qualifications.

52. In addition, the test would also aim to assess the collective competence of both the superfund’s corporate and trustee boards to ensure that they each have the appropriate range of skills, knowledge and experience to run the superfund and its pension scheme, based on the complexity of the business model. For the trustee board, this could also involve an assessment of the board’s ability to provide effective challenge to the corporate board. For both boards we would expect to see an appropriate balance of pensions, financial and investment experience.

Question 13

In your view, are there any other elements that should form part of a potential integrity test, conduct requirement or competency test?

Governance

53. Good governance will be important to the successful operation of superfunds. This includes not only the governance of the superfund structure as a whole, but also the governance of the superfund’s corporate and trustee boards. The key to promoting good governance will be to ensure that the appropriate checks and balances are in place and that potential conflicts of interests are well managed.

The corporate board

54. Decisions made by the corporate board will have a direct impact on member outcomes.

55. We therefore propose that the corporate board would need to demonstrate that it has an appropriate number of independent non-executive directors (NEDs) to effectively hold management to account. In assessing independence, TPR could, for example, take into account provisions within the UK Corporate Governance Code, such as a NED’s relationship with the corporate body or wider corporate group and whether they have been appointed in an open and transparent manner.

56. We also propose that the corporate board would need to demonstrate that it has plans to monitor and manage any conflicts of interest and that these are regularly reviewed. The ‘appropriate’ number of independent NEDs could be prescribed or left to the discretion of TPR.

Question 14

Should there be a minimum requirement on the proportion of independent NEDs on the superfund’s corporate board or should this be left to TPR discretion? If so, what would be a suitable proportion?

The trustee board

57. The superfund’s trustee board will play a crucial role in representing the best interests of all members transferring into the superfund’s pension scheme. It will also act as an important counterweight to the corporate board through providing effective challenge where necessary. As a result, it will be important that the trustee board:

- is made up of persons independent of other entities within the superfund

- can make objective decisions

- has the right level of skills, knowledge and experience to manage a complex scheme with potentially multiple benefit structures

58. To meet these aims, it has been suggested that the trustee board should consist entirely of independent trustees. Independent trustees still have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of members and they would likely have a level of knowledge and experience to effectively and objectively run a superfund pension scheme. While independent trustees are often professional trustees, they can also be lay trustees.

59. To guard against potential conflicts of interest and further protect the independence of the trustee board, it has also been suggested that we apply a non-affiliation requirement, similar to that used for multi-employer DC pension plans. This could require trustees to be independent of anyone who provides services to the superfund (such as advisory, administration or investment services) as well as requiring trustees to be recruited through an open and transparent appointment process.

Member representation

60. There is a current requirement that at least one third of the membership of the trustee board of a pension scheme are member nominated, subject to certain exemptions (the member nominated trustee (MNT) and member nominated director (MND) requirement).

61. There are compelling arguments that this requirement is inappropriate for superfunds. They could comprise very different constituencies of members with varied benefit structures as well as distinct historical, social and demographic backgrounds. In addition, if the trustee board were required to consist entirely of independent trustees, they would be exempt from an MNT/MND requirement. We do not therefore propose to apply the MNT/MND requirement to superfunds.

62. However, we recognise that there must be other channels through which members’ views are represented should there be no requirement for member nominated trustees (or directors).

63. One option could be to add the provision of ‘adequate systems and processes to ensure members’ views are represented’ as a condition of authorisation. Although this would allow for a degree of flexibility, we believe that it could risk members of different superfunds experiencing different levels of service. It might also be difficult to define what ‘adequate’ looks like in this context.

64. A more prescriptive option would be to require superfunds to establish member panels. The purpose of such panels would be to ensure that members’ views are brought to the attention of trustees and to facilitate members’ engagement with the scheme.

65. The panels could be established on a purely consultative basis, where the trustee board would be required to consult the member panel on certain decisions. Alternatively, the panels could have a stronger role provided it does not impede the board’s ability to carry out its legal duties.

66. The panels could also be required to publish annual reports on their activities and on member issues, which could be made publically available. We believe that doing so would enhance transparency and comparability for employers and pension scheme trustees considering transfers to a superfund.

67. On balance we think that members’ interests are best served by a requirement for superfunds to establish member panels, and propose to proceed on this basis. We would welcome views on whether this would be effective and proportionate.

Question 15

Should superfund trustee boards consist entirely of independent trustees?

Question 16

Should there be a non-affiliation requirement for the appointment of trustees to a superfund’s trustee board?

Question 17

Should superfund trustee boards be subject to the MNT/MND requirement?

Question 18

Should superfunds be required to establish member panels? Would such panels be an effective and proportionate way of ensuring that members’ views are represented?

Agreements between the corporate and trustee boards

68. Some superfund models suggest that the rights and responsibilities of the corporate and trustee boards are set out in legal agreements. We want to be clear that such agreements should not impede trustees in carrying out their legal duties. We do however see how they could be useful in providing clarity. We therefore propose that any such agreements should be submitted to TPR on application for authorisation and that the superfund would need to explain these arrangements if TPR felt that trustees’ discretion was being fettered.

Systems and processes

69. In order for a superfund to be run effectively, it will need robust administrative systems and governance processes. Therefore, as part of authorisation, the corporate entity of the superfund will need to satisfy TPR that it has the right systems and processes in place to support the business model being proposed. In this chapter, we discuss how a potential ‘systems and processes’ requirement, drawn extensively from the DC master trust authorisation regime, could work. We envisage that the requirement will be underpinned by a future TPR Code of Practice.

Risk management

70. Both the corporate and trustee board of a superfund would need to demonstrate that they have processes in place to assess and control risk. These processes should enable each board to identify, document and manage operational, financial, and compliance risks; both internal and external. Both frameworks would need to enable their respective board to maintain effective oversight of their respective entities. TPR could, for example, ask to see evidence of how each board reviews and updates their risk registers, how this is supported by accurate and timely management information, as well as plans to review the overall effectiveness of the framework on an ongoing basis.

Investments

71. Both the corporate and trustee boards would need to demonstrate that their investment governance is appropriate for the complexity of their investment arrangements, so that risks are properly managed. This could, for example, include documented evidence on how they set their investment objectives, risk appetite and investment strategy and how risks are identified, monitored and, where appropriate, mitigated on an ongoing basis.

Continuity strategy

72. We define certain funding level triggers and the responses that would be required to protect the best interests of members in Chapter 3. We therefore propose that superfunds would need a continuity strategy in place to assess and address the potential issues that might arise as a result of a trigger being breached. We also propose that the continuity strategy should set out the response required should certain other events occur. Events would for example include:

- TPR withdrawing authorisation

- an insolvency of the corporate entity

- the corporate entity being unlikely to continue as a going concern

- the investors wishing to end the relationship with the superfund

IT requirements

73. Both the corporate and trustee boards would need to demonstrate that their IT systems are capable of supporting the business model being proposed. This could cover areas such as data security, functionality, ongoing maintenance and disaster recovery.

Member records

74. The trustee board would need to demonstrate that they have processes in place to ensure member records are kept accurate and regularly reviewed.

Security

75. Both the corporate and trustee boards would need to demonstrate that they have processes in place to protect personal data and sensitive information as well as protocols for managing data breaches. It will be the responsibility of the pension scheme to ensure that the member data is appropriately protected. As part of authorisation it should be evidenced that there are procedures and protocols in respect of member data, identifying the risks and any breaches, including outsourcing to third parties, and the plans in place to respond to incidents.

Member complaints

76. Superfunds would need to demonstrate that they have an adequate complaints procedure in place. This could include evidence that they have processes in place to enable the resolution of complaints and that members are informed of their rights.

Third party providers

77. We recognise that the corporate board and/or the trustee board may want to engage third party providers. Although both boards will be able to delegate certain tasks and decisions, they will ultimately remain accountable. We therefore propose that they should be required to submit any Service Level Agreements and demonstrate how they will monitor delivery against these on an ongoing basis as part of authorisation, or before engaging the third party provider. A change in person(s) responsible for delivering key services would form part of the significant events framework discussed in Chapter 4.

Conditional authorisation

78. There may be cases where a superfund does not have all systems and processes in place prior to becoming operational. In such instances we propose that TPR could grant conditional authorisation subject to certain conditions being met, for example, the scheme appointing a minimum number of trustees within a certain timeframe.

Question 19

In your view, would the areas outlined in this section enable TPR to assess the effectiveness of a superfund’s systems and processes? If not, what alternatives would you propose?

Question 20

Are there other areas that should be included as part of the systems and processes requirement for superfunds?

Financial sustainability

79. The financial sustainability and adequacy of a superfund is arguably the most critical and difficult area for the new legislative framework. It needs to deliver improved protection to members moving into superfunds, while balancing the need to maintain reasonable affordability for employers, and sufficient potential profitability to attract investment capital.

80. Superfunds can potentially already operate within the existing occupational pension framework. However, the current framework is not optimised to deal with the new risk profile posed by superfunds (as outlined in Chapter 2). It is important that a bespoke framework is designed to manage these risks and maximise the benefit superfunds can bring to the delivery of DB pensions, and to the wider economy.

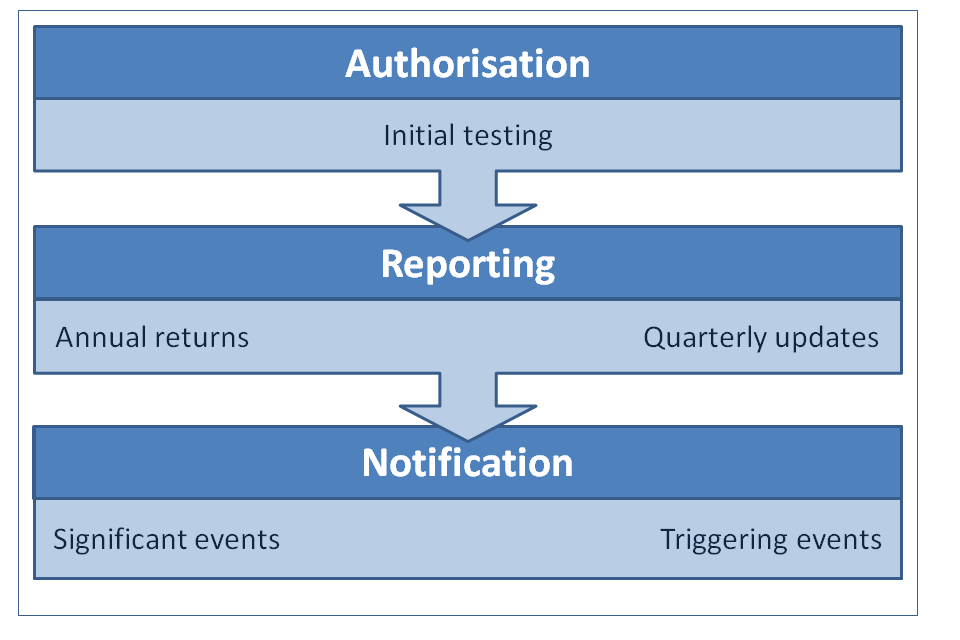

81. We set out in Diagram 2 the process for assessing and monitoring financial sustainability. Financial sustainability will be assessed at commencement and superfunds will need to demonstrate they meet the criteria for authorisation. Thereafter, they will need to continue to demonstrate that they meet the requirements and to notify TPR if certain events happen in relation to the funding of the superfund and take any required or relevant action as a result.

Diagram 2

82. Our priority is to ensure that member benefits are adequately protected and that the risk of regulatory arbitrage of the insurance buy-out market is minimised. However, we welcome innovation in the pension industry and therefore aim to provide a framework which enables new models to develop and flourish, with as many schemes as possible able to afford entry into a superfund if it gives them a greater chance of paying or securing member benefits in full.

83. Our intention is not to duplicate a less costly version of the insurance buy-out model; doing so would be a form of regulatory arbitrage that would hurt the growing insurance buy-out market that provides a high level of security to DB pension scheme members. Nor do we wish for superfunds to be a way for employers to offload underfunded schemes, when it would be in members’ best interests to remain in the employer’s scheme, and benefit from deficit repair contributions.

84. Our ‘gateway’ proposals discussed in Chapter 5 will help guard against schemes which are able to buy-out, or have a realistic prospect with sponsor support of achieving buy-out in the foreseeable future, from entering a superfund. And our minimum standards proposals, which would require schemes to be well funded on a prudent basis at outset, would guard against the inappropriate consolidation of under-funded schemes.

Options for ensuring financial adequacy

85. There are a number of approaches to ensuring financial adequacy and sustainability. There are important questions both about the structure of the regulatory approach, and whether it is appropriate to the nature and profile of risks presented by superfunds. There are also questions about where the various funding and other metrics should be pitched to deliver an appropriate level of member protection, while balancing the competing calls of employer affordability and investor profitability.

86. The fit of the financial adequacy regime to the emerging superfund models will partially depend on whether they are seen (and therefore regulated) as predominantly insurance-like vehicles, or as occupational pension schemes. Superfund proposals have some similarities to insurance, given that the employer link is broken, and the security of members’ benefits in the long term is provided by a capital buffer. We have therefore set out options for defining the financial adequacy required both within a DB pension framework and also in an insurance like framework. We have set out four options in total – 3 options based on progressively greater transparency of funding and capital requirements to increase the levels of confidence within the occupational pensions framework (options (i) – (iii)) and a further option based on an insurance-like regime (option (iv)).

DB pensions framework

87. Current DB occupational pension legislation provides a framework within which risk can be effectively managed in order to balance the competing priorities of member protection, and employer affordability. In the main, as evinced in our green and white papers, the system has been largely successful in delivering this balance.

88. The existing DB occupational pension framework was not set up to deal with the particular risks posed by superfunds. We therefore propose to add a further stochastic modelling requirement for authorisation and ongoing supervision which will more robustly assess the purpose, objectives, and risks of superfunds: we are seeking views on the possible approaches and parameters for those requirements.

89. We propose to set up a framework based on a high probability of success. In our consultations with the industry, we have been told that a 99% probability of paying benefits in full is achievable. This seems like a reasonable starting point for the debate – we might therefore require superfunds to demonstrate at least a 99% probability of paying or securing all members’ benefits in full.

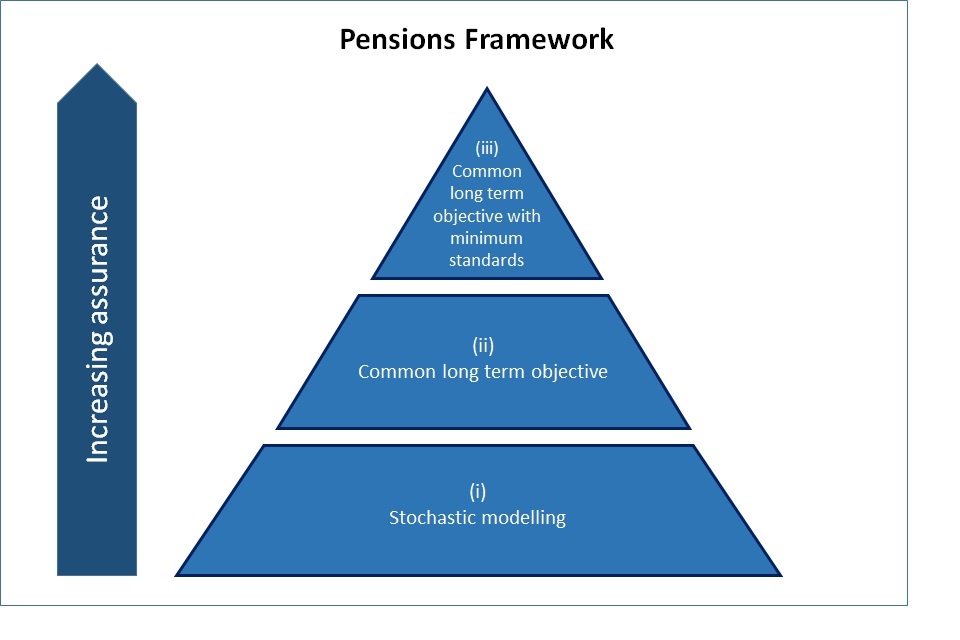

90. We have considered 3 options for demonstrating this level of confidence within the DB occupational pensions framework as demonstrated in Diagram 3. The parameters in the 3 options below are all intended to be consistent with the principle of the superfund demonstrating at least a 99% probability of paying or securing all members’ benefits in full. Supporting each of these approaches, we would expect TPR to issue guidance setting out how a superfund would be expected to evidence this high probability of success. With all approaches, TPR would continue to regulate the superfund as an occupational pension scheme, with, for example, powers in relation to technical provisions and recovery plans.

Diagram 3

(i) Stochastic modelling approach

91. In this approach we would add a stochastic modelling requirement to the existing DB framework. We would require the superfund to undertake their own stochastic modelling. This would need to demonstrate that there was at least a 99% probability of members benefits being paid or secured over the lifetime of the superfund, both at authorisation and then annually with the annual valuation.

92. While this approach gives flexibility to superfunds to develop new models of provision, the requirement to demonstrate a continued high probability of paying benefits in full should in itself constrain the amount of investment risk and profit taking, and help to determine the level of the capital buffer required.

93. If this option were taken forward, it could be argued that we would be creating an internal model regime where the capital buffer is set by the regulated entity in a manner approved by TPR. The aggregate level of funding and capital would have to meet the overall probability of success and TPR would retain its role in relation to scheme funding etc. History suggests that this approach requires a strong regulator with the power to reject a model it considers to be inappropriate, otherwise this may result in a weak regulatory regime. We would therefore aim to ensure that TPR had the necessary powers.

94. Stochastic modelling is likely to be a feature of most potential options for determining financial adequacy, and there is further discussion of parameters and supervision in the section on modelling at paragraph 161 below.

95. It is important to note that the pension scheme within the superfund will also be subjected to the same requirements as any other occupational DB pension scheme with respect to scheme funding and investments.

(ii) Common long term objective approach

96. We are concerned that simply adding a scheme based stochastic modelling requirement onto the existing framework may not provide adequate safeguards. Therefore, in line with the white paper proposal for all DB pension schemes to set their statutory funding objective in the context of a long term objective, we will require all superfunds to be authorised using a standard long term objective. This approach therefore adds a more specific objective with a clear time by which the objective should be achieved, against which the superfund proposal will be assessed. It is again underpinned by the principle of demonstrating a high probability of success, but here, all superfunds would be authorised based on their probability – to be demonstrated by stochastic modelling – of meeting the standard long term objective, within a clear time-frame.

97. It is worth noting that option (i) will include a similar sort of framework, but in that case set by TPR as part of its regular supervisory role as a result of proposed changes in the new DB Scheme Funding Code of Practice.

98. The timeframe to achieve the long term objective is intended to coincide with a point in time when the majority of members have retired and the superfund scheme has reached or even passed peak cash-flow. The timeframe also needs to reflect the fact that transferring schemes will be closed and maturing even as superfunds are growing in size and consolidating new schemes. This could be a fixed target date, such as 2040, but on balance we think this needs to be scheme specific, as more mature schemes should need less time to reach their peak cash-flow or even be in run-off.

99. We might expect the superfund, both pension scheme and capital buffer, to be funded on a basis such that over the timeframe it will be able to maintain or achieve a level of funding that would allow trustees to either secure the benefits through a buy-out or to continue paying benefits as they fall due on a very low risk basis.

100. Another option might be to set a specific long term objective of securing benefits with an insurance company. But as there is no requirement on traditional DB occupational pension schemes to have a long term objective to buy-out, an objective based on ongoing funding against an ‘authorisation basis’ may be more appropriate rather than require any specific action to be taken.

101. Regardless of the above, we think that the authorisation basis should reflect a prudent estimate of the cost of winding up a scheme and buying out all the benefits. This would be for a scheme that has matured to the point most of its members have retired and at a level which should otherwise allow it to continue to run on with very low investment and funding risk.

102. We propose that the authorisation basis is set valuing the liabilities on a basis equivalent to the cost of buying out the liabilities with an insurer by using assumptions broadly consistent with a typical pension scheme’s technical provisions, which includes a prudent allowance for scheme specific mortality assumptions, but based on the following:

- a gilts flat discount rate, that is no allowance for any expected out-performance above gilts in the discount rate or illiquidity premiums

- a further margin of 7.5% of liabilities in respect of a reserve for expenses, adverse longevity and other demographic experience as well as other margins for prudence

- an allowance for other factors specific to superfunds which could be set out in a TPR Code of Practice or legislation for this purpose, for example, the treatment of options which we would expect to be calculated on broadly ‘cost-neutral’ terms regardless of how factors were determined in the ceding scheme

103. An alternative would be to set the authorisation basis considering scheme specific circumstances, for example adjusting the 7.5% margin to allow for scheme specific factors. For example, if the superfund has hedged all mortality risk then an additional margin of 7.5% may not be appropriate although we would expect the cost of hedging to be included the superfund scheme’s technical provisions.

104. We propose that the superfund, both pension scheme and capital buffer, is then required to demonstrate that it will be able to be fully funded on an authorisation basis to a very high probability of, for example, 97.5% by the earlier of 2040 and the date the scheme reaches peak cash-flow. On and after that date the objective would be to retain sufficient capital to ensure there is at least a 97.5% probability of being 100% funded on the authorisation basis in one year’s time which would be broadly consistent with the approach as set out below under option (iv) from this date onwards if a risk-based approach is to be used for that option.

(iii) Common long term-objective and minimum standards approach

105. It could be argued that an approach that relies on assessing the probability of success using stochastic modelling still gives insufficient assurance that members’ benefits will be adequately protected, even in the context of a clearly defined objective and broadly consistent approach and assumptions.

106. Clearly the outputs of the modelling supporting any of the options will be highly dependent on the internal working of the model, and on the underlying assumptions used. These will have to be carefully assessed when superfunds are authorised as well as monitored when superfunds are supervised on an ongoing basis. But this may not be enough. The uncertainty inherent in modelling approaches suggests that some additional safeguards relating to some key parameters may still be needed to guard against excessive risk taking, profit taking, or under-funding.

107. This approach therefore builds on the common long term objective approach, but adds on a number of specific minimum standards. These might include requirements for taking on new business and ongoing authorisation such as:

- the superfund scheme on its own without any capital buffer should be at least 87.5% funded on the ‘authorisation basis’ or something broadly equivalent, an alternative might be to set the scheme a separate long term objective – perhaps a two-thirds probability of reaching 100% funding on an authorisation basis within the standard timeframe

- the capital buffer should be sufficient for the scheme assets plus the capital buffer to equal at least 100% of the ‘authorisation basis’ or something broadly equivalent

- any remaining capital buffer should be paid into the superfund scheme if the scheme assets plus capital buffer is less than 90% of the ‘authorisation basis’ or something broadly equivalent

- the risk taken in the investment strategy should be constrained, perhaps to limit annual funding volatility to less than 5% pa, for example, by employing a test based on the PPF’s methodology for assessing stressed values of assets for PPF levy calculations

Insurance type framework

(iv) Annual balance-sheet approach

108. This approach would require a superfund to annually demonstrate its probability of success by meeting a required level of solvency based on a prudent estimate of buying out benefits with an insurance company, comparing liabilities and assets, including any capital buffer.

109. The superfund, in terms of its pension scheme and capital buffer could simply be required to be fully funded for buy-out at all times. However, a superfund will be exposed to adverse experience over time. This could be a longevity extension, increasing buy-out costs, or adverse investment experience. There is therefore a case for a superfund to have excess funds above 100% of buy-out as a buffer against adverse experience.

110. A capital buffer against adverse experience could be fixed or dependent on the risks that the individual superfund faces. For example, the superfund could always be required to be at least 105% funded compared to buy-out.

111. Alternatively, there could be a variable funding level above 100% that is reflective of the risk being run and the specific likelihood that the superfund will remain 100% funded over the next year. This would allow for all the factors that might impact on the assessment over the next year (for example a 97.5% probability of still being 100% funded on a buy-out basis in one year’s time).

112. This approach seeks to protect member benefits by carefully defining a level of funding a superfund is required to maintain and demonstrate at all times in terms of its pension scheme and capital buffer. Some may argue that it leaves less room for innovation within the sector and may ultimately be more suited to an insurance type proposal that seeks to reduce risk to very low levels, despite the fact that the various parameters can be flexed to reflect the risk appetite of a long term occupational pension scheme. In addition, the associated costs could significantly undermine the ability of superfund vehicles to attract adequate investment.

113. However, others may argue that this approach provides for a more objective way of assessing solvency because it directly tests the cost of securing benefits in the buy-out market. Others would also argue that a balance sheet approach can provide for a wide range of risk appetite. For example, a nil capital requirement would only require assets to be equal to buy-out liabilities with no buffer against adverse experience, whereas a one in 200 capital requirement would provide protection approaching that of a life insurance company. It could be argued that since a superfund is economically very similar to an insurer (even if the legal structure is different) because there is no recourse to a corporate sponsor the balance sheet approach to solvency is a more suitable approach.

114. Although this treats the superfund more like an insurance vehicle, it will still have at its heart an occupational pension scheme. This option could therefore be combined with some elements of the minimum requirements discussed in paragraph 104 particularly relating to the authorisation level of funding for the superfund scheme, payment of any remaining capital into the superfund scheme, as well as the conditions, if any, we might wish to place on the investment strategy.

115. The options presented above are not an exhaustive list of the potential mechanisms to assess and control the financial sustainability of a superfund. There may be elements of each option that could be combined with overall preferred options. For example, calculating a risk based capital buffer could be included in any of the above options. In addition to the requirements of any of the options above, a balance sheet valued at market values could be prepared, and published.

Question 21

Should superfund financial adequacy be regulated through a pensions based funding requirement approach with an added test of probability of success or an insurance based approach using a Solvency II type balance sheet?

Question 22

Which of the suggested models would best ensure appropriate financial adequacy, and balance the interests of the various parties? Are there elements of other options that you think should be combined with your preferred option?

Question 23

Does a 99% probability of paying or securing members’ benefits over the lifetime of the scheme adequately protect members’ benefits, and effectively balance the competing priorities of employer affordability and member security? If not, what would an appropriate probability be, and why?

Question 24

Should a superfund have a long term objective to secure benefits with an insurance company?

Question 25

Is the proposed authorisation basis suitable for this purpose? If not, what basis, if any, would you propose for this purpose?

Question 26

Is a 97.5% probability of being 100% funded on an authorisation basis by the earlier of 2040 and the date the scheme reaches its estimated peak cash outflows consistent with the principle of a superfund having a 99% probability of paying or securing members’ benefits at all times?

Question 27

Is the earlier of 2040 and the independently assessed point at which the superfund’s membership reaches peak maturity a reasonable target date?

Question 28

Are the additional minimum standards in (iii) needed, in order to ensure a high level of protection for member benefits? In particular, are the additional minimum standards (that the superfund scheme itself is funded to 87.5% on the authorisation basis) required for every scheme entering a superfund?

Question 29

Should superfunds be required to publish an annual balance sheet using market valuations and including liabilities valued on a buy-out basis together with a buffer fund based on the Solvency II approach?

Schemes reaching buy-out funding

116. There is a question about whether schemes in a superfund should be required to secure benefits with an insurance company at the earliest possible opportunity when funding levels allow, or whether it is acceptable for them to continue to run-off benefits when funding levels would allow buy-out to be considered.

117. Allowing a superfund to continue to operate once the scheme is fully funded to buy-out level could be seen as regulatory arbitrage between the superfund sector and the life insurance sector. The justification for allowing superfunds to operate without the employer link but with a lower level of protection than an insurer is to provide a better way of managing some DB schemes where there is no realistic prospect of buy-out. This serves the interests of both employers and members. Consequently, it can be argued that once funding has risen to a level where it could be bought out, the rationale for remaining in a regime without a sponsoring employer, but with lower protection than an insurer could provide, falls away and the scheme should be obliged to leave the superfund regime by buying out benefits with an insurer. We envision TPR would be involved in this process and additional powers required. We would welcome views.

Question 30

Should superfunds be required to secure benefits with an insurance company as soon as practicable, once the scheme assets reach the buy-out level of liabilities?

118. Superfunds could intentionally be set up to maintain a level of funding within the superfund scheme so that the scheme will never have a realistic chance of buying out benefits at some future date. Even if there is no specific requirement for superfunds or their scheme to buy-out at the earliest opportunity, we might seek to mitigate any underfunding risk within the superfund scheme through the minimum requirements on scheme funding levels as set out in paragraph 104 above. This could also include a separate long term objective for the superfund scheme to reach a buy-out level of funding at some future date regardless of approach to financial adequacy or requirements to buy-out.

Question 31

Should superfunds be required to maintain a minimum level of scheme funding regardless of approach to financial adequacy? This could include a separate long term objective for the superfund scheme itself to reach a buy-out level of funding but to a lower level of probability than the superfund as a whole?

Proposed test for failure

119. As well as being authorised based on a suitably high probability of paying or securing members’ benefits, we propose that superfunds should also be authorised based on demonstrating a very low probability of failure. We suggest that an appropriate metric would be a less than 1% chance of them triggering a wind up in extremis (described in the winding-up triggering event below) over the duration of the superfund. We should not underestimate the difficulty and potential subjectivity of this assessment, in particular the assumptions that will need to be made about the type of scheme entering the superfund and the extent to which benefits provided by the PPF will converge with superfund scheme benefits over the lifetime of the superfund.

Question 32

Is the failure test in relation to the PPF funding level proportionate and what probability of failure is acceptable?

Funding level triggers and responses (superfund triggering events)

120. In addition to the main financial adequacy regime, we think that for members and PPF levy payers to be adequately protected, there will need to be a series of underpinning trigger points that describe what must happen if funding levels fall below certain prescribed limits.

121. We therefore propose to define a series of superfund triggering events together with the proposed consequences of these events should funding levels reach the specified levels. For authorisation, the superfund governing documentation should set out the superfund triggering funding levels and the required responses. We also propose to require the trustees to notify TPR and to take the relevant actions should the funding level fall to below these trigger levels. TPR will have the power to intervene if the triggering level is not acted upon. We welcome views on what additional powers, if any, TPR would need to intervene should a trigger be breached.

Question 33

What powers should TPR have to intervene should a funding level trigger be breached?

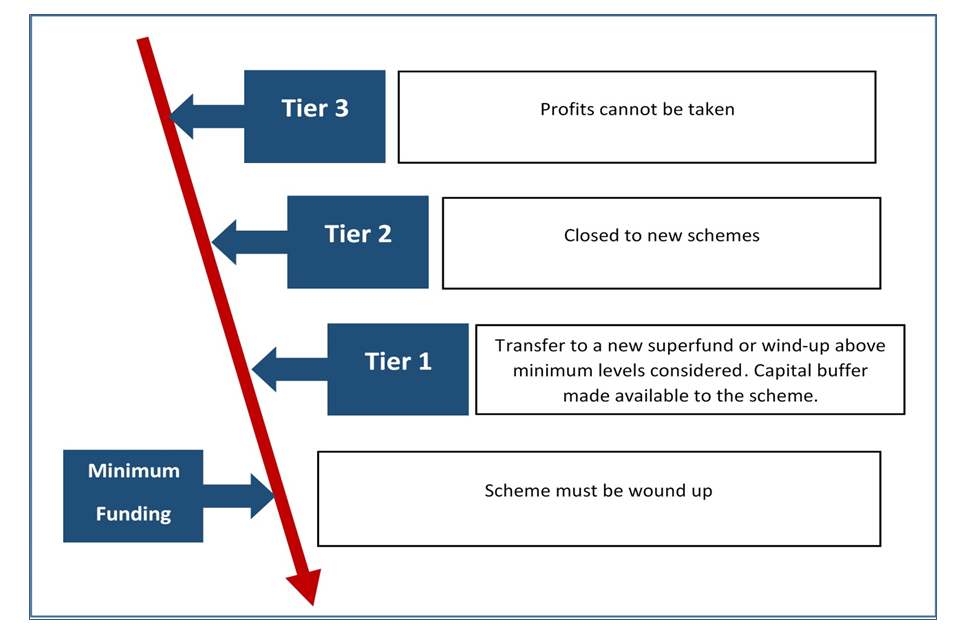

122. As Diagram 4 illustrates, we propose that there should be a hierarchy of superfund triggering events at different funding levels. The 4 required responses to superfund triggering events being proposed are:

- minimum funding – to force wind up of the superfund scheme in extremis and to pay any remaining capital buffer into the scheme in respect of the wind up

- Tier 1 – to pay any remaining capital buffer into the superfund scheme and to enable either a transfer of the superfund business to another superfund or to wind up above PPF levels but potentially less than 100% of full benefits

- Tier 2 – to prevent new business being written

- Tier 3 – to restrict when profit can be extracted

123. We discuss these triggers and responses in further detail below.

Diagram 4

Minimum funding: winding up the superfund in extremis

124. As the schemes within a superfund may be classed as DB occupational pension schemes, we believe that they should be protected by the PPF, so that members continue to be protected from significant losses. But the PPF and its levy payers also need to be protected from the risk posed by a superfund failure. A minimum funding level trigger could therefore be defined as the superfund’s scheme assets and capital buffer falling below that required to buy-out PPF level benefits.

125. However, there could be a significant period of time between the decision that a superfund should be wound up and the liabilities being transferred out of the scheme. We therefore propose that a margin above that required to buy-out PPF level benefits should be allowed for in order to provide some protection against further deterioration in the funding level during the time taken to wind up the scheme.

126. We propose that the trigger for automatically winding up a superfund should be on a consistent basis for all superfunds, depending on the definition of failure (for example, 105% of that required to buy-out PPF level benefits on a prescribed basis). Reaching the minimum trigger point should require the superfund to automatically start a wind-up process and allow trustees of the superfund scheme to have full access to the assets in the capital buffer. This trigger will protect the PPF and PPF levy payers, ensuring that members of a superfund will still be eligible for PPF compensation if that proved necessary.

127. The winding up process should be triggered automatically as the difficulty of exercising discretionary powers in such scenarios could lead to long delays in wind up. There may be an incentive in such cases for the superfund to delay the wind up in the hope the scheme may recover on its own. By this point the capital buffer will have been injected into the scheme, investors will be unable to lose more money but may have a chance of taking future profit if the scheme’s position improves. However, this will come at an unacceptable level of risk of member benefits deteriorating further and therefore become a greater cost for the PPF.

128. We propose a statutory wind up trigger as soon as the risk of a claim on the PPF is too high. The PPF recently published The 2019/20 Pension Protection Fund Levy Consultation. In this consultation the PPF state a preference for the new regulatory framework for superfunds to include a statutory wind up trigger in order to protect the PPF. In the period before the legislative framework for superfunds is in place (or if a statutory wind up trigger is not implemented) the PPF propose that the levy calculation for superfunds reflects the risk that the funding level in a scheme within a superfund may deteriorate to a level significantly below that required to fund PPF level benefits. This should provide a strong incentive for the superfund to put its own wind up trigger in place at a funding level above that required to buy-out PPF benefits.

129. This minimum funding level trigger would force the start of a wind up. Rather than a single one-off assessment, however, we propose that the assessment of whether the minimum funding level has been reached should be judged over a timescale, (for example over 3 months) over which the triggers described above are breached before the wind up process needs to begin. This is to allow for the volatility in funding due to market movements. A single assessment that the minimum funding level has been breached should still result in an agreed recovery period being put in place to allow the scheme the chance to recover or investors to put more money into the superfund.

Question 34

At what level above fully funded on the S179 basis should the winding up trigger be set?

Question 35

Is 3 months an appropriate period of grace to allow for any volatility in investments to recover before triggering a wind up?

Question 36

Is this minimum funding level trigger sufficient to provide adequate protection for the PPF while mitigating the risk that short term volatility might force a superfund into the PPF when it still might have a very good chance of meeting the long term objective?

Tier 1: a trigger to pay any remaining capital buffer into the superfund scheme and to enable a transfer of superfund business to another superfund or to wind up the superfund scheme above minimum PPF levels

130. A minimum funding level trigger to wind-up in extremis serves to protect the PPF and to ensure that members of a superfund will still be eligible for PPF compensation if that proved necessary. However, having been transferred to a superfund, members still might reasonably expect to get full benefits even in the case of a superfund which is deemed to be failing but is not an immediate risk to the PPF.

131. We therefore propose a higher funding level (Tier 1) trigger that would be breached should the scheme plus the capital buffer funding level fall to less than 90% on the authorisation basis (or something broadly equivalent). If this trigger is breached there should be a requirement for the trustees of a superfund to transfer the members to a new superfund, while the trustees of the superfund scheme would require full access to the remaining capital buffer in order to facilitate the transfer to a new superfund. We propose that the assessment of whether the triggering funding level has been reached should not be made on the basis of a single assessment but that there should be a timescale (for example, 3 months) over which the trigger is repeatedly breached. A single assessment that the triggering funding level has been reached should however result in a recovery period being agreed.

132. Although the Tier 1 trigger is intended to require a transfer to another superfund there may not be another superfund willing to take on the business, particularly if no additional employer capital or sufficient funding is available, or if all superfunds are struggling in challenging economic conditions. In this circumstance, trustees might consider it still to be in the best interests of members to allow the scheme to continue rather than to wind up the superfund. However, we would not expect the superfund to be allowed to continue indefinitely without adequate capital backing or without a firm expectation of being able to secure full benefits within a relatively short period of time.