Ending the proliferation of deferred small pots

Updated 22 November 2023

Ministerial Foreword

The growth of deferred small pots has been a longstanding issue that presents huge challenges to the Automatic Enrolment pensions market. Without intervention it is anticipated that deferred small pots will result in wasted administration costs of a third of a billion pounds per year by 2030 for pension schemes, severely reducing the value for money they can provide to their members.

In January, I launched a Call for Evidence seeking input from the pensions industry on the way to address the growth of these deferred small pots, following the significant work undertaken by the PLSA and ABI led, Small Pots Co-ordination Group. I would like to thank all members of the Group, including the Chair, Andy Cheseldine, as well as all of those who responded to this Call for Evidence, providing your valuable insight and knowledge on this challenging and complex issue.

As set out within our Call for Evidence, deferred small pots are a drag on the pension system, acting as a disincentive for members to engage in pensions, reduced buying power at retirement or in some cases results in them being lost altogether. These pots cause challenges for pension providers who have to administer these unprofitable pots, reducing the value for money they can provide to their members.

I previously set out my determination to tackle this issue and drive the agenda forward to help ensure that a better functioning and more efficient pension market that meets the needs of more engaged members. Today, I am setting out a decisive way forward built around the multiple default consolidator model – ensuring that a member’s deferred small pots are brought together into one pot.

This consultation sets out our proposed framework for this model which will enable a small number of authorised schemes to act as consolidators for deferred small pots. We will look to take forward primary legislation to implement a statutory framework as parliamentary time allows, with further detail underpinning this to be covered in secondary legislation – which will be subject to formal consultation. In the meantime, I will look to form a delivery group with the pensions industry and other interested parties, building on the successful model of the existing Working Group, to ensure that the outstanding design questions are tackled and ultimately an automated default consolidator system is implemented that is cost effective and successfully delivers our objective of ensuring members achieve greater value for money from their pensions.

In the longer-term, a simpler system of workplace pension saving could emerge to deal with the fundamental issue that new pension pots are created each time someone starts a new job, for example, a lifetime provider model with each saver stapled to a ‘pot for life’, which may go further to solving this for existing and future pots. However, it is right we focus now on delivering this solution to the small pots issue we face as no matter what the future of workplace pension saving holds it is essential deferred small pots are consolidated to the benefit of schemes and most importantly members.

The DWP has published a number of documents today, all designed to drive better outcomes for pension savers. These are all part of a wider government agenda to improve opportunity for investment in alternative assets including in high growth businesses and improve saver outcomes. We believe that a higher-allocation to high-growth businesses, as part of a balanced portfolio, can increase overall returns for pensions savers leading to better outcomes in retirement. In addition, we want to ensure that our high-growth businesses of tomorrow can access the capital they need to start up, scale up and list in the UK. DWP have been working closely with HMT on this wider package which was set out by the Chancellor in his Mansion House speech.

Laura Trott MBE MP

Minister for Pensions

Introduction

The first part of this document sets out the feedback the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) received to the call for evidence which ran between 30 January 2023 and 27 March 2023.

The call for evidence concentrated on widening the evidence base on the scale and characteristics of the growth in the number of deferred small pots and on the potential solutions to tackle their continued growth. It focussed on two large-scale automated consolidation solutions – a ‘default consolidator’ model and a ‘pot follows member’ model – whilst recognising the potential positive impact of other actions, including member exchange and enabling greater member engagement.

The second part of this document sets out the Government response and a consultation with further policy questions to gather additional views and evidence on the proposed automated consolidation solution to address the growth of deferred small pots.

Part 1: Government Response to the call for evidence – ‘Addressing the challenge of deferred small pots’

Chapter 1: Summary of Responses to Call for Evidence

About the Government Response

1. This document forms the Government’s response to the public call for evidence[footnote 1] that was launched on 30 January 2023 and ran for 8 weeks, closing on 27 March 2023. This sought views on, and evidence to support, the development of two large-scale automated consolidation solutions – a default consolidator model and pot follows member – whilst also recognising the potential impact of other measures, including member exchange, and encouraging more member engagement to help mitigate the growth in the number of small pots.

Responses to the call for evidence

2. We received 52 responses to the call for evidence, this included responses from the following sectors:

- 19 pensions schemes providers both trust-based and contract-based

- 18 pensions industry professionals

- 3 employer/employee representative groups

- 1 consumer group

- 8 financial services providers

- 3 pension law firms

3. Part 1 of this document highlights the main feedback raised in response to call for evidence questions but is not an exhaustive commentary on every response received.

Our key assessment criteria

Question 1: Do you agree that these are the appropriate key criteria to inform development of a market-wide small pots consolidation solution? Are there additional/different criteria to apply?

i. Delivery of overall net benefits for members through improved value for money outcomes, achieving a meaningful impact on the number of existing, and flow of new, deferred pots

ii. Complements member engagement on their savings journey/retirement planning

iii. Supports a competitive, sustainable and more efficient workplace pensions market (trust and contract-based schemes)

iv. Minimising complexity and administrative burdens for employers

v. Commands confidence in the system for savers and taxpayers

Summary of Responses

4. The call for evidence set out a series of criteria against which solutions should be assessed. We asked whether these were the right criteria to guide our analysis. There was broad support from respondents that the key criteria were appropriate, with respondents agreeing that the delivery of overall net benefits for members was right to be prioritised as the lead criterion.

5. Respondents stressed that it would be important to design a streamlined solution minimising burdens for pension providers, ensuring that consolidation was not assessed at an individual level. These respondents acknowledged that automatic consolidation would have overarching benefits for all members by reducing overall costs but may not always be beneficial for all individual members. However, respondents would be concerned if there were a requirement to assess at an individual level as this would reduce the automation of any solution and thus increase costs. However, it would be important that members best interests are at the heart of the overall solution, which includes the need to deliver better outcomes for members.

6. Separately, respondents stressed that it would also be important that the solution captured as many of the smallest deferred small pots as possible and that the risk of matching errors should be minimised.

7. Other respondents suggested consideration should be given to the solution being straightforward and cost effective for providers to implement whilst maintaining a competitive landscape for the workplace pension market. Some respondents felt members should be safeguarded from making poor decisions. Others also pointed out that the solution should work cohesively with other changes to the pensions system, for example the introduction of pensions dashboards.

We agree that the criteria are the right ones and are useful in framing the trade-offs. We think the key criteria is the first one in that any action needs to deliver a meaningful impact on the stock and flow of small pots, which is why we firmly believe that a form of mandated automatic solution will be necessary over and above any member-initiated activity to seriously move the dial.

National Pensions Trust

Member engagement

Question 2: How do you think we can increase member-initiated consolidation and what are the opportunities, risks, and limitations of member-initiated consolidation?

Summary of responses

8. The majority of respondents agreed with the call for evidence and the conclusion of the 2020 DWP-chaired Small Pots Working Group[footnote 2], that member-initiated consolidation should be encouraged and has an important role in helping to tackle the growth of deferred small pots. However, respondents acknowledged that the impact and scope for members to initiate the consolidation of their pensions was limited.

9. A number of respondents raised the impact of the introduction of pensions dashboards may have on member engagement, with most agreeing that dashboards will simplify the process for members interacting with their pensions and may prompt members to consolidate their deferred small pots and therefore help to reduce the number of small pots within the system.

Although for launch, Pension Dashboards will not be able to trigger transactions, it has the potential to trigger engagement which may then prompt off-dashboard consolidation to take place.

The Investing and Saving Alliance (TISA)

10. Additionally, some respondents argued that pensions dashboards should be fully operational before a small pot solution is implemented in order to gauge its impact on member interaction with their pensions.

Pensions dashboards should be fully implemented before any small pots automatic transfer solution is developed. An understanding of how they impact consumers’ behaviours should then be sought. As it stands, pensions dashboards will not directly allow someone to consolidate their pension pot.

Association of British Insurers (ABI)

Market innovation

Question 3: We would be keen to understand from respondents, how far do you believe market innovations can go in reducing the growth of deferred small pots?

Summary of Responses

11. The majority of respondents thought that innovation within the market could reduce some of the growth of deferred small pots over time. Their view is that technology in recent years has driven innovation within providers, for example, mobile savings applications and smoother transfer of pots and some respondents have suggested that these innovations could help reduce administration costs and make transactions simpler and cheaper. This would reduce the overall cost of transfers of deferred small pots for consolidation.

12. However, there was strong feeling within the responses that relying on market innovation to reduce the number of deferred small pots is limited by regulation, with respondents pointing to scams regulations and existing pension protection regimes as areas that prevent schemes from innovating further.

13. Throughout the responses there was support for pensions dashboards as a step in the correct direction to improve innovation and simplify engagement. Engagement needs to be driven by technological advancements led in partnership by pension schemes and government backed schemes like Value for Money and pensions dashboards. Despite respondents stating that market innovation is important and has a part to play, many believe this alone would not solve the issue of deferred small pots.

We welcome, and are actively engaged with, tech developments and innovation to support our members to transfer in their deferred pots. We are deploying tech solutions with specialized tech service providers to support our membership with transfers, including searching for their pots and submitting the information they need to action the transfer. But we think this approach will have limited impact compared to automatic consolidation solutions.

NOW: Pensions

Which pots should be in scope for automatic consolidation?

Question 4: Do you consider one of the values below to be the most appropriate starting limit for eligibility for automatic consolidation, and why – or is there an alternative value?

a) £1,000

b) £2,500

c) £5,000

d) £10,000

Summary of Responses

14. Overall, there was no clear agreement from respondents on what the appropriate maximum pot size for consolidation should be, with some respondents noting that the maximum pot limit suitable for automated consolidation may vary depending on the overall consolidation solution chosen.

15. Respondents agreed with the call for evidence that setting the maximum pot size at the right value was a fundamental decision. Of the four options set out option (a) £1,000, received the most support from respondents. Respondents suggested that the benefits of starting at this level included the fact that it would capture the majority of small pots without overly affecting the market.

We recommend you start at £1,000 as this will sweep up a significant proportion of the small pots, without destabilising the market. Start low and then turn up the dial.

The Lang Cat

16. However, some respondents felt that £1,000 – the lowest limit within the call for evidence – was still too high. A maximum limit of £500 was proposed by some respondents who referred to the Small Pot’s Working Group study[footnote 3], which showed 74% of small, deferred pots fall under £1000, with a large proportion being between £50-£250. It was felt that this would still sweep up a large number of the existing stock of small pots but would have less impact on the market (compared to a higher pot limit). It could be regularly reviewed and increased gradually over time as the market adapts to a reduced number of deferred small pots. On the other hand, some respondents felt that a higher limit should be set, but gradually phased in over time.

We think that starting at £1,000 is the right approach, from the options given in the paper. We would, though, prefer a lower limit, potentially as low as £500. Following the data cited in the consultation paper, a threshold at £1,000 would address roughly 75% of the issue. We do not think the evidence supports a higher figure.

People’s Partnership

The optimal starting limit for eligibility for automatic consolidation will need to be informed by cost-benefit analyses, but we currently believe that the starting limit should be no more than £1,000, and that an even lower starting limit may be appropriate. Our rationale for this focuses on establishing the optimal level given the need to balance the systemic gains for removing cost inefficiencies with potential risk of detriment to individual savers.

Which?

We believe a figure of £2500 would be appropriate as it will remove the smaller pots from the system – those which have the most potential to lead to the issues identified by the call for evidence. Further we feel that a staged approach should be considered, starting with the smaller pots of up to £500, followed by pots of up to £1000, then pots of £2500. This will allow any issues and concerns to be dealt with and learning applied before the next stage is implemented.

M&G

17. Setting the maximum too high increases the risk of member detriment if their pots are consolidated to a poorer value scheme, while also increasing the potential risk of market distortion. However, a balance needs to be achieved: some respondents suggested that the limit needs to be set at a high enough value to ensure that enough unprofitable pots are eligible for consolidation to ensure that automated solutions are cost effective and able to deliver overall net benefits to members.

Questions for providers

Question 5: How many deferred pots does your scheme have within each of the above breakdowns, how many of these are within AE charge capped default funds, and what is the total AUM of deferred pots for each of these breakdowns?

Summary of Responses

18. The data responses to the call for evidence cover roughly 20 million deferred pots worth less than £10,000, most of which were within AE charge-capped default funds and represent an estimated £30bn in assets. The majority of these pots are below £1,000 in value, though this only represents an estimated 14% of total assets in this sample. The average value of a pot smaller than £1,000 is approximately £350.

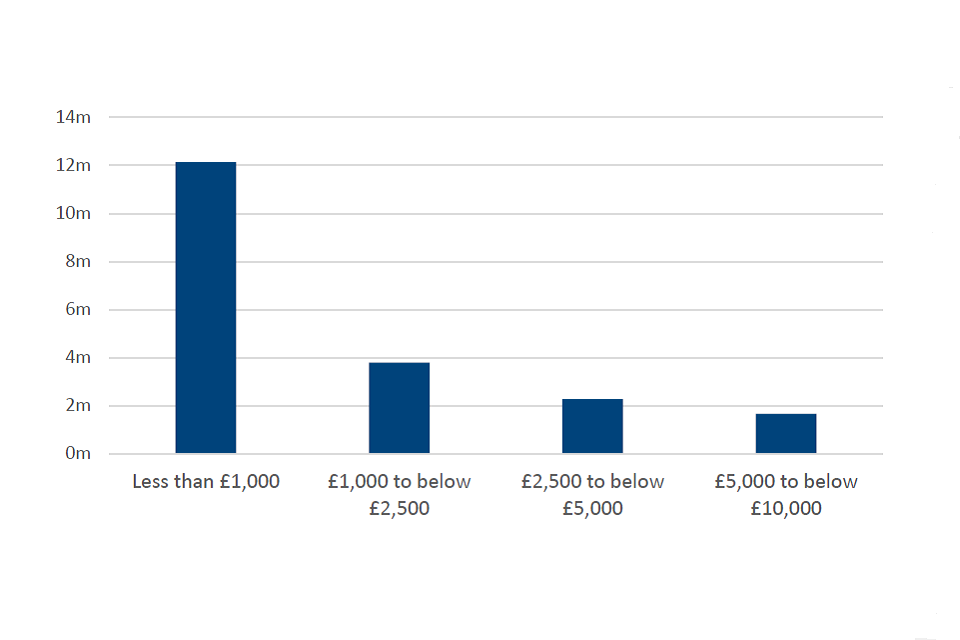

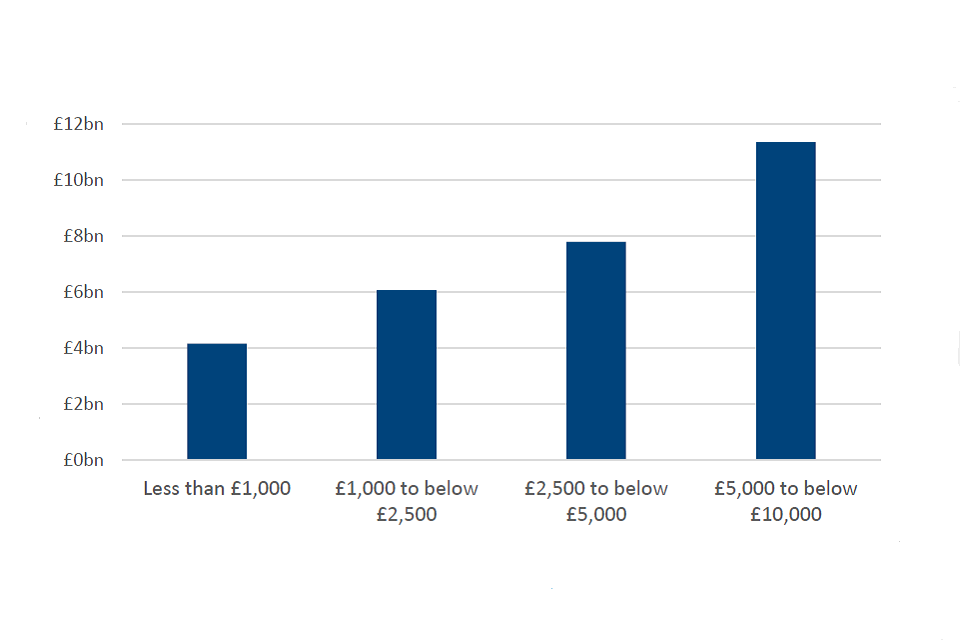

Table 1: Breakdown of number of pots and assets by the size of deferred pot.

| Pot size | Number of pots | Estimated value of assets |

|---|---|---|

| Below £1,000 | 12.1 million | £4.2 billion |

| Between £1,000 and £2,500 | 3.8 million | £6.1 billion |

| Between £2,500 and £5,000 | 2.3 million | £7.8 billion |

| Between £5,000 and £10,000 | 1.7 million | £11.3 billion |

Question 6: What is the average cost of a pot transfer (ceding and receiving) for your scheme, within AE charge capped default funds?

Summary of Responses

19. The cost of transferring a pot varied by respondent, and by how many associated costs were included in the calculation. Most cost estimates were between £15 and £40 for both receiving and ceding a pot (meaning total costs of a transfer of between £30 and £80), with no consensus on whether it cost more to transfer a pot in or out. Several respondents commented that they expect transfer costs to be less than £10 if the process became more automated.

Question 7: Would the increase in pot transfers associated with an automated small pots solution affect your investment strategy? If so, how, and why?

Summary of Responses

20. Responses to this question were mixed. Some responses indicated that the impact of an increase in transfers on investment strategy would largely depend on which small pots solution was chosen, and at what size the pot limit was set. However, multiple providers said that an automated solution will mean an increase in the number of transfers out of any schemes with a lot of small pots. Respondents said this increase in transfers is likely to reduce their willingness to invest in illiquid assets as they would need more liquidity to be able to manage this change.

Question 8: What is the average cost of administering a pot for your scheme, does this differ by active/deferred, or by size? If so, what is the difference in costs and why?

Summary of Responses

21. From the responses received, the cost of administering a pot averages out at roughly £20 per year, typically ranging between £5 and £25. There was no consensus from respondents on whether active or deferred pots cost more to administer. The responses that said active pots cost more, pointed to the extra costs associated with collecting and investing monthly contributions. Those that said deferred pots cost more, referenced the increased likelihood of deferred members engaging with services asking for transfers and drawdowns.

Question 9: What is the breakeven point for administering pots for your scheme, does this differ for active/deferred pots?

Summary of Responses

22. Responses to this question varied depending on charging structures and how the breakeven was calculated and typically ranged between £1,000 and £6,000, with no significant difference between active and deferred pots. Most responses said that pots worth less than £1,000 would be below their breakeven point.

Question 10: Do you think there should be a minimum pot size limit for pots to be eligible for automatic consolidation? If so, what do you think this limit should be, and what should happen to pots below that limit?

Summary of Responses

23. Respondents noted that if a minimum pot size is to be introduced, further thought needs to be given to the message it sends to members when it comes to pension saving, given that it may diminish the value of small pension pots to members and act as a disincentive for saving. Setting a minimum pot size limit would most likely affect low earners, part-time workers, younger workers, and members who change jobs more frequently.

Those in low paid temporary employment, who are the category most likely to have multiple micro pots, already face material difficulties in building up adequate pension savings, and excluding them from the potential benefits of consolidation would further disadvantage this group.

Eversheds Sutherland

24. Included in the responses to this question we received a significant amount of feedback in relation to refunds of ‘micro pots’. There were strong levels of agreement across the responses that the introduction of refunds of the smallest pots was not a wise policy, with respondents arguing that it would undermine the core principles of automatic enrolment.

25. In addition, refunding pension pots could reduce future retirement incomes for members whilst also being logistically difficult and expensive to implement. However, some respondents felt that refunds were worth exploring further, especially for the smallest value pots, where the cost of transfer is likely to outweigh the value of pot.

Question 11: Do you agree that setting a prescribed period for a pot to be classified as deferred is the most appropriate solution – and what period of time would be appropriate, and why? If not, what would be a more suitable approach?

Summary of Responses

26. A significant number of respondents agreed that the most appropriate option for classing a pot as deferred would be to set a prescribed period of time where no contribution is made. Respondents considering this to be more effective with a default consolidator approach than with a pot follows member approach, given that a pot follows member approach may be more suitably linked to when an individual starts a new role. Almost all respondents suggested that a minimum of 6 months should be used as the time period.

In terms of a time period, we would suggest 6 months. Our reason being that this timeframe marks a long enough notice period for a proposed change of job, and therefore justifies the inactivity time.

My Pension Expert

27. However, some respondents felt a longer period of time would be more appropriate. Some made the case for a period between 12 and 24 months after the last employment-related contribution was received as this would allow for the majority of outstanding employment matters to be dealt with. It would also indicate that the deferred members’ account is unlikely to receive further employment-related contributions. Overall, there was broad levels of support for setting a specific time period for a pot to be classified as deferred but some issues were raised which would require further consideration. This included the question of what happens to members who have a sustained period of absence from work, for example, those on maternity leave, sick leave, or seasonal workers. There is a risk that an individual’s pension could be consolidated through inactivity when their intention is to resume making contributions.

It seems to us that a period of 12 months might be appropriate for these purposes.

Mercer

28. The final option proposed in our call for evidence, where the point of deferral is triggered by a member leaving employment, was supported by some respondents, primarily those who favoured the pot follows member approach. There was a consensus that a minimum time would not be relevant, because the trigger to initiate the automatic transfer will be when a member starts a new job with another employer. This method was favoured by pension providers as it would require a pull mechanism by the new provider. In a push system, a pension provider is unlikely to have information on where the saver has moved, therefore making the transaction difficult. Respondents also acknowledge this approach would be difficult for those members who had multiple jobs.

Market wide automatic consolidation solutions

Question 12: Do you agree with the summary of potential benefits and implications of the default consolidator/s approach, and if not why?

Question 13: What are the key benefits / risks of a multiple default consolidator and single default consolidator approach, including impacts on the wider pension market, and employers?

Summary of Responses

29. There was broad agreement, across a range of sectors, including pension providers and consumer/employee representative bodies, in their responses, on the potential benefits and implications of the default consolidator(s) approach described in the call for evidence. Respondents suggested a range of additional benefits:

- there is a greater degree of quality control over where a pot can be consolidated to, compared to pot follows member, given the likelihood that a consolidator scheme would be expected to demonstrate the highest standards of value for money for their members.

- some responses outlined how the consolidator solution could increase member engagement, as a result of a relationship being created between the member and their consolidator.

- both solutions reduce the number of transfers compared to pot follows member, therefore the administration cost of the entire model would be reduced.

- the consolidator solution is more flexible for a member than the pot follows member solution, given that they could exercise choice over their consolidator schemes, whereas in pot follows member they would be consolidated into the scheme used by their new employer. Additionally, some respondents felt a default consolidator approach could work hand in hand with a lifetime provider model.

- the multiple consolidator approach has less of an impact on the market than the single consolidator solution. In addition, a multiple consolidator approach enables competition within the pension market, which will incentivise innovation from consolidators leading to an improved value and experience for the member.

30. However, some respondents presented concerns of the default consolidator(s) approach that were not included in the call for evidence, including:

- there is an increased risk that members may be concerned about scams if they are contacted by a scheme they do not recognise.

- both models place a large number of pots with one or a small number of consolidators, this could result in a concentrated risk for member detriment if the scheme(s) experienced difficulties.

- there could be a risk that if schemes were unable to effectively match an individual’s deferred pot to a consolidator scheme, a member could end up with multiple consolidated pots.

- if a carousel approach were to be selected, where members are allocated a consolidator when they have made no active choice, this may cause problems in cases where one consolidator performed worse than others; resulting members questioning the rationale behind the allocation of the consolidator scheme.

- a single consolidator could result in the creation of a monopoly over deferred small pension pots. Respondents had concerns around the impact that this could have on the workplace pension market.

- some respondents felt that a single consolidator approach could result in a lack of competition reducing the incentive for the consolidator to innovate and potentially result in a no better than average product for the member.

Question 14: Who should be able to be a consolidator; should there be a limited number, and, if so, how many, and why?

Summary of Responses

31. Respondents considered that if a multiple consolidator approach was taken forward, the number of consolidators should be limited. Some respondents suggested that there would be a number of Master Trusts which would be most suitable to act as consolidators.

32. Some respondents suggested that the number of consolidators should be capped, and that around half a dozen consolidators may be optimal. However, other respondents argued that limiting the number could discourage competition within the market, though respondents acknowledge this should be balanced with ensuring the approach is as simple as possible to deliver.

If a multiple consolidator option was pursued, the aim should be to have a limited number of highly regulated, low cost schemes. Restricting the number of consolidator providers would simplify the market for members, and for employers and ceding pension schemes, and make effective regulation easier.

Trades Union Congress (TUC)

33. Additionally, some respondents made the argument that the current regulatory framework would need to be enhanced for those schemes applying to be a consolidator and appropriate standards would be required for consolidators to adhere to. Respondents suggested that consideration be given to setting a minimum level of assets a provider must hold before they can operate as a consolidator. Other respondents noted that consideration would need to be given to how the role of a consolidator would align to the Value for Money framework.

Question 15: What would be the appropriate approach to giving members choice in terms of choosing their consolidator, and what approach should be taken if the member did not make an active choice?

Summary of Responses

34. There was strong support for members to be encouraged to interact with their pensions and that members should be given every opportunity to choose which provider their pots are consolidated into.

35. However, some respondents noted that the growth of deferred small pots has in part resulted from a lack of member engagement. As such, respondents believed that it is not possible to simply rely upon members to engage and choose their consolidator. One of the proposals which received support from respondents was a carousel model, recognising that this would be reliant on there being enough providers to participate. It was suggested that there would need to be some parameters set for allocation through a carousel approach as this should not be randomised for each member.

36. Other suggestions on how a consolidator could be allocated to a member included the following:

- a member’s older pots should be consolidated with their last/current active pot provider.

- if a member has multiple pots with different providers, their pots should be consolidated to the provider with the greatest pot value.

- pots could be consolidated into the member’s oldest deferred pot.

Question 16: Do you agree with the above summary of potential benefits and implications of the pot follows member approach, and if not why?

Question 17: What are the key benefits / risks of a pot follows member, including impacts on the wider pension market, and employers?

Summary of Responses

37. Most respondents, from a broad range of sectors, including pension providers and consumer / employee representative bodies, agreed that the call for evidence covered the key benefits and limitations of the pot follows member approach. However, some respondents suggested that there were further benefits of pot follows member, which were not outlined in the call for evidence. These include:

- giving the employee the option to choose if their pot should follow them at the time of enrolment into their new employer workplace pension scheme in order to minimise further burden on business.

- this approach may result in less duplication of administration due to fewer pots in the system, in addition to this there was a suggestion that approach could be underpinned by the pensions dashboards system, reducing the need for schemes to manually search for a new active pot.

- savers would feel more in control of their pot as the principle of a pot following from employment to employment could be easier to understand.

- this approach does not break the principle of inertia for members who do not wish to make an active decision, but will still achieve a significant level of pot consolidation for deferred members.

38. The following concerns were raised in addition to those outlined within the call for evidence:

- some respondents queried how a pot follows member system would interact with the value for money framework and what would determine ‘value for money’ for a pot transfer.

- some respondents cautioned what would happen when the consolidated pot reaches the maximum value and then does not follow the member to the next employer.

- other respondents questioned if there would be pots stuck in a ‘transitory’ state as employees move jobs so frequently so that their pot is not transferred to the new employer pension scheme before they leave that employer for a different newer employer.

- many respondents questioned what would happen to multiple job holders and especially those who have multiple small pots. Linked to this, questions were raised about how much member choice would be baked into a pot follows member system, especially if those multiple job holders wished to consolidate their pots into a single pot.

- Respondents noted that due to the frequency of transfers likely required as part of a pot follows member approach this would generate great deal of liquidity and flow in the pension system.

- there were also questions around member consent as part of the pot follows member solution. For example, how and when in the process, a member should provide consent to transferring their pot to another employer pension scheme.

Question 18: Of the two solutions set out above what is your preferred approach, and why?

Summary of Responses

39. As expected, there was not a clear preferred solution across the responses received. The pot follows member approach received more support from pension providers, across both contract-based and trust-based schemes. However, less than half of the responses suggested that this was the optimal approach. Respondents who favoured the pot follows member approach suggested that it would better support member engagement.

It is our view that pot follows member is the most member-centric solution as it provides the easiest means by which members can retain their pension savings in a single pot. We also believe that this concept would be easier understood by members than a potentially random consolidator scheme that they have had no prior relationship or engagement with.

Legal and General

40. The default consolidator approach also received a significant amount of support from respondents, again from both contract-based and trust-based pension providers, with the multiple consolidator solution achieving marginally more support than the single consolidator approach. For those who favoured a single consolidator approach one of the key benefits respondents gave was the simplicity this solution would offer. For those respondents who believed a multiple consolidator approach would be the most effective, there was recognition of the potential benefits in terms of its ability to build scale and benefit from the economies that these bring – including being able to pass on reduced costs to members.

We favour the multiple consolidators approach. As we outline elsewhere in this response, we see the development of large, well governed, pension schemes as most likely to lead to good value for money for savers. We also think that building scale will assist with other government policy objectives, specifically investment in less liquid assets.

People’s Partnership

Question 19: Are there any further / fresh or hybrid solutions that are worthy of consideration?

Summary of Responses

41. Throughout the responses there was broad agreement that the appropriate approach to addressing the growth of deferred small pots was either through a pot follows member or a default consolidator approach. However, a number of respondents suggested that further exploration of a lifetime provider model should be undertaken – given the benefits this would bring for member choice. Those respondents who supported this approach believed this would encourage active decision making and help members take ownership of their retirement planning by creating a relationship between member and pension provider.

By moving to a ‘member decides’ model, we believe there can be a greater resolution to the small pots issue, which is more likely to lead to higher engagement from members, better and more informed consumer choices, and larger pots during accumulation.

Link Group

42. Some respondents felt a lifetime provider approach would be challenging to administer especially given the possibility that payroll services would need to make contributions to multiple different schemes dependent on individual employees’ choice of scheme. Respondents also felt that this approach could be damaging to the employer/employee relationship resulting in employers becoming less engaged with their employees’ pension scheme. In addition, some felt that this approach could result in a loss of business to schemes that offer a competitive, low-cost service, if schemes are able to invest significantly in marketing campaigns to attract members away from the schemes which their employer might have chosen.

It would be logistically very demanding, if not impossible, for employer payroll services to set up and accurately reconcile contribution payments to multiple different schemes on an individualised basis in this way (in theory, every employee in the workforce could be in a different scheme under this proposal).

Eversheds Sutherland

Question 20: Should there be an initial focus on managing the flow of new pots or removal of the existing stock, and where does the balance of impact lie for each of the solutions presented?

Summary of Responses

43. There was no overwhelming support either way on whether stock or flow should be prioritised. Respondents were clear that to successfully tackle the challenge of deferred small pots, both the stock and flow of small pots would need to be addressed. Some outlined that the question of prioritisation is dependent on a few different factors such as the model selected, pot size and transaction costs.

We do not have strong views on whether the stock or the flow should be prioritised first.

We believe it is clearly necessary in this case to deal with both the stock and the flow. In terms of the solutions, it might be tempting to deal with the stock by using the default consolidator and the flow by using pot follows member, but this wouldn’t fully solve the problem for many people who will still find their workplace pensions savings are in at least two different places.

Federation of Small Businesses (FSB)

Question 21: What could be done to incentivise, build momentum, and help build market and member confidence in member exchanges, either now or in future? Would this be best taken forward by industry or government?

Question 22: Could a member exchange form part of a hybrid model alongside one of the large-scale consolidation solutions discussed in Section 5, or with a large-scale consolidation solution acting as a backstop?

Summary of Responses

44. A number of respondents, from various sectors, felt that a member exchange solution has some merits. However, others felt that it could potentially complicate the overall solution to the small pots problem and believed that the ‘Member Exchange Pilot’ alone would not achieve the levels of consolidation required to address the small pot problem. Instead, respondents favoured a statutory solution to the problem that would cover the whole of the workplace pensions market. However, some respondents considered that member exchange could help with the reduction of the stock of small pots and could deliver some improvements in advance of the roll-out of a market-wide solution, or opportunity to provide insight / learning for the delivery of a market-wide solution.

45. Those who responded to this question felt that in order for a member exchange pilot to form part of the solution, there would need to be significant regulatory safeguards to reassure trustees that their actions are deemed to be in the best interests of the member. This would need to be coupled with clear communication from pension schemes to members who would need to be notified of any potential transfer and the rationale behind the transfer.

46. Respondents felt that if a large-scale consolidation solution was progressed, then coupling with a member exchange system would be unnecessary as the member exchange would only address the trust-based portion of the market, and would no doubt cause further complication as the contract-based market would be excluded from participating in a pilot, potentially creating a dual system within the workplace pensions market.

Question 23: Do you agree that same scheme consolidation has a key role to play in the wider consolidation of deferred small pots, and can act as a foundational measure to larger market-wide solutions? If not, why?

Question 24: If your scheme currently does not undertake same scheme consolidation, what are the reasons behind this and what would be required to overcome this?

Summary of Responses:

47. Throughout the responses there were mixed views on the effectiveness of same scheme consolidation in terms of dealing with the problem of small pots. Some respondents believed that if government mandated same scheme consolidation this could distract from solving the overall issue of deferred small pots and that it should be left to providers to consolidate pots themselves. It was suggested that this solution could create a greater problem for providers who offer a range of products to their members – which may result in members having different arrangements in the same scheme dependent on the decisions made by their previous employers, which could act as barriers for consolidation. Some respondents noted that same scheme consolidation could be useful alongside either pot follows member or a default consolidator approach, but would not be completely effective on its own.

48. Those respondents who argued that same scheme consolidation would not be an appropriate approach, were consistent in the opinion that providers may face barriers when it comes to consolidating pots. It was felt that this would be particularly true for contract-based providers, with some respondents suggesting that while they may be able to display a member’s multiple pensions within a single view they would not be able to merge them without the members’ consent due to the nature of their contracts.

We link all pots related to one member. So, members with more than one pot pay only one administration fee, can see all their savings in one place and only get one set of member communications. The resulting efficiencies for the member’s outcome are the same as if the pots were combined.

We don’t combine the pots by moving all the money into a one-pot account. Reasons for this include potential complications where different employer charges apply, so we need records to distinguish between the member’s accounts with different employers. Linking rather than combining the pots supports ongoing verification and reconciliation activities. It also enables members to exercise their right to access each pot separately for tax purposes, if they want to.

NOW: Pensions

Equality Act

Question 25: As part of this call for evidence we would welcome views on how protected groups are currently impacted by the deferred small pots issue:

A. whether the impact differs between groups and in comparison, with non-protected groups

B. what mitigations providers are putting in place and the impact of each of the options on protected groups

C. and how any negative effects arising from them may be mitigated.

Summary of Responses

49. Multiple respondents recognised that deferred small pots are often held by low earners and multiple job holders, women, ethnic minorities and other under pensioned groups who are making minimal pension contributions and who move jobs more frequently due to insecurity of part-time work.

50. Respondents felt that consideration should be given to other protected groups including older members and those with disabilities, with particular attention to be paid to how industry would communicate changes to their pots to these groups. Respondents were also keen to ensure that any solution does not exacerbate the Gender Pensions Gap.

51. Concerns were also raised in relation to societal views or religious beliefs being considered when a pot is consolidated, including ensuring that members such as those within Sharia funds were not disadvantaged or excluded from any automated consolidation solution.

52. Some respondents raised the point in relation to the interaction of maternity and/or paternity leave and considering how to protect members pots from being transferred out for consolidation during a period of leave. This point was also raised in response to Question 11 regarding what period of time would be appropriate to define a pot as deferred.

Part 2: Public consultation on proposal to resolve the small pots issue

About this consultation

Who this consultation is aimed at

The Department for Work and Pensions welcomes input from: pension scheme providers; trustees; scheme managers; members of workplace pension schemes; employee representatives; trades unions; consumer groups; employers and employee representative groups; pension industry professionals; and members of the advisory community and any other interested stakeholders.

Purpose of the consultation

This document includes:

- a summary of responses received to the call for evidence, and

- the Government’s response with a set of policy consultation questions exploring next steps.

Scope of consultation

This consultation applies to Great Britain. Occupational pensions are a devolved matter for Northern Ireland. We will be working closely with counterparts in Northern Ireland at the Department for Communities in relation to the matters set out in this consultation.

Duration of the consultation

Part 2 – the Consultation, will run for 8 weeks, starting on 11 July 2023, and close on 5 September 2023. Please ensure your response reaches us by that date as any responses received after that date may not be taken into account.

How to respond to this consultation

Please send your consultation responses to:

Email : [email protected]

Government response

We will publish the government response to the consultation on the GOV.UK website.

How we consult

Consultation principles

This consultation is being conducted in line with the revised Cabinet Office consultation principles published in March 2018. These principles give clear guidance to government departments on conducting consultations.

Feedback on the consultation process

We value your feedback on how well we consult. If you have any comments about the consultation process (as opposed to comments about the issues which are the subject of the consultation), please email them to the DWP Consultation Coordinator. These could include if you feel that the consultation does not adhere to the values expressed in the consultation principles or that the process could be improved.

Email: [email protected]

Freedom of information

The information you send us may need to be passed to colleagues within the Department for Work and Pensions, published in a summary of responses received and referred to in the published consultation report.

All information contained in your response, including personal information, may be subject to publication or disclosure if requested under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. By providing personal information for the purposes of the public consultation exercise, it is understood that you consent to its disclosure and publication. If this is not the case, you should limit any personal information provided, or remove it completely. If you want the information in your response to the consultation to be kept confidential, you should explain why as part of your response, although we cannot guarantee to do this.

To find out more about the general principles of Freedom of Information and how it is applied within DWP, please contact the Central Freedom of Information Team:

Email:[email protected]

The Central Freedom of Information team cannot advise on specific consultation exercises, only on Freedom of Information issues. Read more information about the Freedom of Information Act.

Data Protection and Confidentiality

For this consultation, we will publish all responses except for those where the respondent indicates that they are an individual acting in a private capacity (e.g. a member of the public). All responses from organisations and individuals responding in a professional capacity will be published. We will remove email addresses and telephone numbers from these responses; but apart from this, we will publish them in full.

For more information about what we do with personal data, you can read DWP’s Personal Information Charter.

Chapter 1: Next steps and Policy proposal

Automated Consolidation Solution

53. Our call for evidence explored two large scale consolidation solutions designed to address the growth of deferred small pots – a default consolidator model and pot follows member and asked for respondents’ views on the potential benefits and implications of both solutions. From the responses we received, it is clear that both solutions have their merits and would support the first key criteria we set out: the delivery of net benefits to members through the reduction of deferred small pots. However, there was no collective agreement across the responses on the optimal approach.

54. Pension schemes, enabled by private pensions policy, have a role to play in enabling greater security in retirement for their members and in supporting economic growth across the country. As part of our plans to drive further consolidation and ensure scale provision in the DC market, we will review the Master Trust authorisation regime, introducing higher Value for Money standards and reassessing duties on schemes laying the foundation for a market formed of a small number of larger pension schemes providing better outcomes for their members. This more consolidated pensions market, will ensure that schemes have the scale and capability to invest a greater proportion of their much more substantial asset pool into productive assets in the UK economy, boosting economic growth.

55. Given this realignment of the pensions landscape, it is important that we consider the solution to the growth of deferred small pots with this context in mind. At the same time the overall aim of delivering net benefits to members must remain the priority. We have carefully considered the potential benefits of both pot follows member and a default consolidator model. Respondents have been clear that both approaches, if designed correctly, would enable the consolidation of deferred small pots and therefore further enable consolidation of the market, whilst reducing the financial burden on providers of the most unprofitable deferred pots.

56. In relation to the pot follows member approach, there was a strong view from respondents that this approach may be simpler for members to understand given their deferred pension would follow them from employment to employment. However, many responses highlighted the risk that a member could move from a well performing scheme to a poor performing scheme which would risk putting the member in detriment, although this risk will reduce over time as a result of our proposed Value for Money framework. Further to this, some schemes suggested that due to the frequency of transfers likely required as part of a pot follows member approach this would require their scheme to become more liquid and reduce their capacity to invest in illiquid assets, working counter to our productive finance focus.

57. Alongside these challenges, our call for evidence outlined the risk that with a pot follows member approach members’ pots may quickly reach the maximum limit for consolidation (even if the maximum pot limit was increased over time) and therefore get stuck with potentially multiple unconsolidated small pots. This would limit the overall level of consolidation unless a significantly higher pot value is set, – however, this would run counter to the feedback received in the call for evidence that suggested that we should start with a lower maximum limit. Additionally, respondents raised other risks including the possibility that a member’s pot will not catch up with them due to frequent job changes and that multiple job holders, who have more than one active pot, present a further complication.

58. On the other hand, when considering the default consolidator approach, it is clear that this approach could align more effectively with our desire for a more consolidated workplace pensions market, with a small number of authorised default consolidators, acting as a consolidator for deferred small pots providing greater value for their members through the economies their scale brings them. Further to this, the proposals for an enhanced authorisation criteria for schemes to act as a default consolidator, discussed further in Chapter 3, could ensure that there is less risk of detriment to members’ deferred pots that are transferred to a consolidator as the consolidator scheme will be required to demonstrate the highest levels of value for money. These small number of consolidators, will be able to generate scale at a greater rate opening opportunities to invest in productive finance benefitting the wider economy.

59. On this basis, we have concluded that the multiple default consolidator model is the optimum approach to addressing the deferred small pots challenge and has the potential to provide greater net benefits to members, ensuring that members eligible deferred pots are consolidated into one scheme.

60. We recognise that this approach will not eliminate the future flow of deferred small pots. However, this approach will result in a significant reduction in the current stock of deferred small pots, whilst also enabling the consolidation of future deferred small pots created. Our call for evidence explored whether priority should be given to addressing the stock or flow of deferred small pots first. There was no clear consensus about whether either should be prioritised. However, respondents noted that neither a default consolidator nor pot follows member approach would truly eliminate the flow of deferred pots as the pots would have to sit deferred for a period of time before becoming eligible for consolidation.

61. In order to stop the creation of new deferred small pots, a more fundamental change to the automatic enrolment framework may be needed. In the future, a simpler system of ‘stapling’, as seen in Australia, (where the members active pension pot is assigned as their pot for life, unless they actively choose an alternative provider) may emerge. This would create an environment which is easier for a member to engage with but is clearly some way off in the UK.

62. In this consultation, we have set out the core framework for a multiple consolidator approach and seek views from respondents on whether they agree with the proposals.

Chapter 2: Analysis of the consolidation solutions

Scale of the Problem

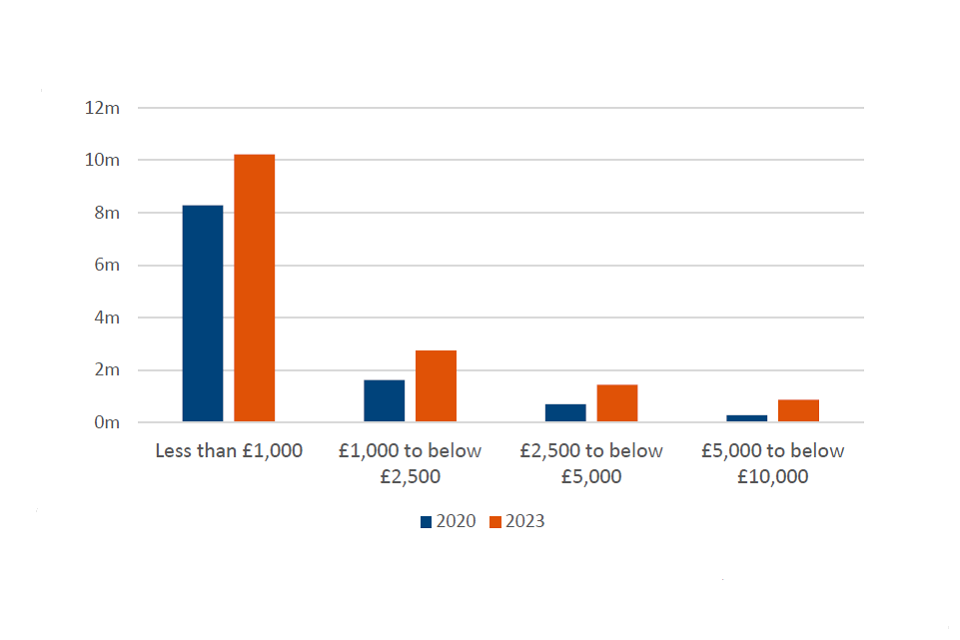

63. In 2020 the Pensions Policy Institute (PPI) said that there was a total of 8m deferred pension pots in the UK Defined Contribution (DC) master trust market, and that this number was estimated to increase to 27m by 2035[footnote 4].

64. The data responses to the call for evidence, however, suggests that the proliferation of deferred pots is likely to be larger than the PPI’s estimate and that there are already roughly 20 million deferred pots worth less than £10,000 across the whole DC market; representing an estimated £30bn in assets.

65. Although we did not receive data responses from every provider, we believe our sample represents most of the market due to the size of the respondents in terms of both members and assets. Not all respondents provided asset value data, so where necessary we have used estimates based on their number of pots.

Figure 1: Number of deferred pots by pot size

Source: Provider data from Call for Evidence

Figure 2: Estimated assets under management in deferred pots by pot size

Source: Provider data from Call for Evidence

66. The majority, 12m, of these deferred pots are worth less than £1,000 (the average value is around £350), however, due to their low value they only account for about £4bn in assets. This represents less than 3% of the assets in the occupational DC market, which has reported asset values of £143bn; of which £105bn is in master trusts (excluding hybrids)[footnote 5]. Extending the scope of deferred pots to include those worth less than £2,500 increases the number of pots by about 30% and more than doubles the amount of assets from £4bn to £10bn; a proportion of which are currently profitable for some providers.

Table 2: Cumulative number of deferred pots and assets below proposed limits

| Pot size | Number of pots | as a % of Deferred pots less than £10,000 | Value of assets | as a % of Assets in Deferred Pots less than £10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below £1,000 | 12.1m | 61% | £4.2bn | 14% |

| Below £2,500 | 15.9m | 80% | £10.2bn | 35% |

| Below £5,000 | 18.2m | 91% | £18.0bn | 61% |

| Below £10,000 | 19.9m | 100% | £29.4bn | 100% |

Source: Provider data from Call for Evidence

67. Since 2020, the number of deferred pots worth less than £10,000 in 5 large providers has grown by roughly 4.5m, from 11m in 2020[footnote 6] to 15.3m now. Of this growth, nearly 2m was in pots worth less than £1,000, from 8.3m to 10.2m.

68. As the majority of those automatically enrolled join a master trust scheme, which represent 89% of all active memberships in DC schemes (with 12+ members, including hybrids)[footnote 7], and the automatic enrolment policy targets low earners and those more likely to change job frequently, these smaller pots are concentrated in master trusts. They also therefore represent a larger share of master trusts’ deferred pots than for other DC pension providers.

Figure 3: Comparison of the number and size of deferred pots in five large schemes between 2020 and 2023

69. In 2020, the PPI estimated that it would take 14 months working full-time on the National Living Wage to create a pot larger than £1,000 while making the minimum contributions[footnote 8]. The NLW has increased since then, but we estimate it would still take just under a year (45 weeks) to create a pot this size.

70. According to DWP analysis of HMRC data[footnote 9], just under half (48%) of the 4.3m instances of people stopping contributing to their pension in 21/22 had been after contribution spells of less than a year. Of which, 68% were after contribution spells of less than six months. The most common reason for stopping contributions (74% of cases) in 21/22 was ending employment, followed by active cessations and becoming ineligible respectively.

71. Since automatic enrolment was introduced, on average more than 1m pots smaller than £1,000 have been created per year, worth more than £400m annually. Without intervention, this rate might increase with the planned expansion of automatic enrolment to 18-21 year-olds.

Benefits of small pot consolidation

72. There are a number of benefits to small pot consolidation for both members and providers. In particular, small pot consolidation should deliver overall net benefits for members through improved value for money outcomes, and complement engagement on their savings journey. For providers, small pot consolidation should support a competitive, sustainable and more efficient workplace pensions market.

Improving financial sustainability

73. The PPI estimated that pots below £4,000 can be unsustainable for providers to manage if they charge through an Annual Management Charge (AMC) only[footnote 10]. The breakeven figures – representing the point below which pots are unprofitable to the provider – that we received from providers as part of our call for evidence varied around this estimate but were consistent that a pot below £1,000 would be loss-making if only charged through an AMC.

74. From our call for evidence, the average size of a pot less than £1,000 is roughly £350. Responses to our call for evidence suggested that on average it cost £20 annually to administer a deferred pension pot, though some estimates were as high as £75, and this did not vary by the size of the pot. The costs associated with administering a pot broadly decreased with the size of the provider, with some estimates as low as the £5-10 range.

75. Alongside administrative costs, workplace pension schemes must pay a levy to cover the cost of running The Pensions Regulator, the Pensions Ombudsman Service and the Money and Pensions Service. Large master trusts are currently required to pay a general levy and a fraud compensation levy totalling £1.36 per member (£0.71 and £0.65 respectively)[footnote 11], and smaller master trusts are required to pay more. The proliferation of small pots means that pots belonging to the same member, distributed across a number of schemes, are generating additional levy charges which will ultimately be met by charges on members’ pots.

76. According to the Pensions Charges Survey large master trusts charge an average of 0.4% AMC[footnote 12], although some charge flat fees to help cover the costs of administration. This means that on average, a pot of £350 being charged 0.4% AMC is only recouping £1.40 per year to the provider, and most cost between £5 and £20 to administer, resulting in an average annual loss of between £3.60 and £18.60 per pot smaller than £1,000. Across the 12m pots below £1,000, this implies current industry losses of up to £225m per year. Our estimates compare well to those produced by the Small Pots Cross Industry Co-Ordination Group that “the proliferation of small, deferred pension pots by 2030 will likely result in wasted administration costs of around a third of a billion pounds per annum”[footnote 13].

Improving member outcomes and engagement

77. As these pots are not covering their administrative costs, members with larger pension pots are effectively being charged more to cross-subsidise them and to cover the £225m annual loss. Higher charges lead to poorer retirement outcomes and we might expect that the problem will only be exacerbated over time as the number of small pots increases. An automated solution will reduce the stock and flow of loss-making small pots leading to industry savings which we expect to be passed on to the member in the form of lower charges, improving retirement outcomes and value for money.

78. DWP research with pension scheme members with multiple deferred pots showed members saw the benefit of having their pots consolidated for them, particularly through reducing the administration burden of having multiple pension pots. Participants liked both the default consolidator and pot follows member solutions for their simplicity, and for bringing their pots together automatically for them[footnote 14].

79. The PPI suggested there could be a link between the increasing number of small pots and the growth in lost pots from £19.4bn in 2018 to £26.6bn in 2022[footnote 15]. The consolidation of these small pots will reduce the likelihood of individuals losing track of their pension savings. Lost pots may threaten an individuals’ ability to achieve adequacy goals in retirement, increase their dependency on the State Pension and means-tested benefits, and reduce their living standards in working life with no benefit during retirement. Multiple responses to our call for evidence said that the increase in transfers associated with any solution is likely to reduce their willingness to invest in illiquid assets. However, if the solution is a consolidator(s) model, the aggregation of these small pots into a few schemes would allow them to generate more scale quickly, opening up investment opportunities into productive assets to support the UK economy. Illiquid investments (such as unlisted infrastructure, private equity and property) can deliver strong returns and help offer diversification to an investment portfolio, which leads to more resilient pension pot values through time for members.

Costs of small pot consolidation

80. Any small pot consolidation solution should: lead to a meaningful impact on the number of existing, and flow of new, deferred pots; be cost-efficient; and minimise any distortion of the workplace pensions market. We anticipate that most of the costs associated with any solution will be in the form of additional transfer costs, though there will also be some initial adjustment costs.

81. Responses to our call for evidence suggested that current transfer costs were not consistent across industry, with estimates of between £15 and £40 for both receiving and ceding a pot (meaning total costs of a transfer of between £30 and £80). The costs of any transfer are made up of: the cost of fund transfers; the cost of moving data; and the administrative costs. The bulk of the costs are currently made up from administration as existing transfer processes are substantially based around member-initiated transfers, on an individual basis. In contrast, small pot consolidation will be automated and not require individual consent, though members would have the option of opting-out.

82. However, there is an expectation that the combination of increased volumes of money and data being transferred and the removal or automation of multiple current steps in the process has the potential to generate large cost savings. Responses to our call for evidence identified that transfer costs would fall below £10 once there was an automated solution.

83. The number of initial transfers will vary by solution and pot size limit, as well as the extent to which people have existing small pots across multiple large providers, which is currently unknown.

84. Given the high concentration of existing small pots amongst a handful of providers, the number and cost of transfers related to the stock could be significantly reduced if some of these providers became consolidators, as they would not have to incur the costs of transferring out the large number of small pots they already have. If all these providers were instead required to transfer out their pots below £1,000, there would be 12m initial transfers which would represent significant costs and administrative burden.

85. However, there exists a trade-off between the number of consolidators and the impact on the stock of small pots, as although fewer initial transfers would be required with more consolidators, there will be less stock outside the chosen consolidators that can be consolidated.

86. A greater number of consolidators may also increase the cost and administrative burden on non-consolidators ceding schemes, as they will have to perform multiple bulk transfers without receiving pots in return. However, in the long-term, we believe the costs associated with these transfers will be outweighed by the benefit of moving unprofitable pots off their books entirely.

87. Under pot follows member, the stock would be dealt with more slowly as not all members will have an active pot in an eligible scheme to be moved to. It would also likely require more bulk transfers, as the number of schemes eligible to receive pots under pot follows member could be larger than the number of potential consolidators, increasing the cost.

88. Once the initial stock is consolidated, the number of annual transfers would also vary by solution. If the limit was set at £1,000 then the maximum number of transfers would be more than 1m pots a year if the current growth rate is maintained, but this maximum would only happen under a solution where a new single consolidator is established. The number of transfers would be less under pot follows member, as not all the people who create a deferred pot will start saving into a new pot, and some of the accumulated pots will become too large to be in scope. The number of annual bulk transfers under multiple default consolidators is likely to be less again, depending on whether the providers who hold most of the new small pots each year are also consolidators, but this seems likely given the high concentration of small pots.

Market impact

89. One of the main criticisms of the consolidator model that respondents have raised is the potential impact it could have on the market compared to pot follows member. Our assessment is that given the existing concentration of small pots in large providers this is unlikely to be significant if the pot limit is relatively low at this stage, consistent with our aim of tackling a deferred small pots problem. If the limit was £1,000 and all £4bn in assets below this was consolidated into a single provider, this is only 4% of the master trust market, and the likelihood is that the chosen provider would already have a large share of these existing assets. Similarly, the master trust market grew by £26.5bn between 2022 and 2023, but estimated growth in deferred pots under £1,000 represents less than 2% of this. The impact on market share becomes even less significant where these assets are divided between multiple consolidators, especially where they already have a large share of the new pots.

Pot follows member

90. Under pot follows member, the stock would be dealt with more slowly as not all members will have an active pot in an eligible scheme to be moved to. It would also likely require more bulk transfers, as the number of schemes eligible to receive pots under pot follows member could be larger the number of potential consolidators, increasing the cost. Further to this, some schemes suggested that the frequency of transfers likely required as part of a pot follows member approach would require their scheme to hold more liquidity and reduce their willingness to invest in illiquid assets, working counter to our productive finance focus. More transfers could also increase the risk of pots not being matched correctly.

91. Additionally, respondents raised other risks including the possibility that members’ pots will not catch up with them due to frequent job changes and that multiple job holders, who have more than one active pot, present further complication.

Single default consolidator

92. Depending on the policy design, a single default consolidator could require all of the existing stock to be transferred to a new entity, at a substantial cost. Alternatively, the stock could be transferred to an existing provider who becomes the single consolidator, which would reduce the number of transfers if they already had a large stock of small pots.

93. The possible benefits of only having one consolidator are the potential for economies of scale, including lower transfer costs and the potential for investing in productive finance. A single consolidator would also be simpler administratively for ceding schemes, and potentially easier for members to engage with. However, as mentioned one of the main criticisms of the consolidator model is the possible downside of lots of pots all being transferred to one provider, with the potential for a distortive impact on the market. This is likely to be most true under the single default consolidator model.

Multiple default consolidator

94. Given the high concentration of existing small pots amongst a handful of providers, the number and cost of initial transfers related to the stock would be lower than under a single consolidator model, if some of these providers became consolidators, as they would not have to incur the costs of transferring out the large number of small pots they already have.

95. However, a greater number of consolidators may increase the administrative burden on non-consolidators ceding schemes, as they will have to perform multiple bulk transfers.

96. The impact on the market becomes less distortive where these assets are divided between multiple consolidators, especially where they already have a large share of the new pots.

Chapter 3: Default Consolidator Framework

The Consolidation Process

97. Our key aim when designing the framework to support the default consolidator approach is to maximise the number of members who can benefit from the consolidation of their deferred small pots whilst minimising the administrative burden on pension schemes. We want to ensure that members have confidence in this system and that the consolidation of these deferred pots will support them in achieving the retirement they want.

98. We have developed the framework for this approach taking into account the substantial work undertaken by the pensions industry over the last few years and further informed by the responses to the call for evidence.

99. We intend to continue this collaboration with industry as we further develop this framework, looking to work with interested parties to develop a viable and cost-effective automatic consolidation transfer process for sending and receiving schemes. We acknowledge the significant amount of work still to be undertaken to successfully implement this approach.

100. The government is keen to build member choice into this approach where possible, to support engaged members to make active decisions about their retirement savings. Therefore, as part of the multiple consolidator approach, we propose that members will be given the option to choose their designated consolidator, alongside the option to opt-out of consolidation if they believe that it is not in their best interest.

A Clearing House or a Central Registry?

101. At present, a scheme seeking to transfer out a pot is not able to see where that member has other deferred or active pots. This lack of transparency in the system, poses a hurdle to the delivery of a multiple consolidator approach. To support the delivery of our chosen approach, there will need to be a central point or system to store and manage the data – allowing sending schemes to identify where a member’s deferred pot should be transferred.

102. We believe there are two options available to support this approach. The first option is the creation of a clearing house that can act as a central body to communicate between the sending and receiving pension scheme, but also contact the member in cases where no active decision has been made regarding the chosen consolidator. Alternatively, we could look to create a central register which providers would have access to in order to match their deferred pots to the consolidator. Below we set out the potential design for both approaches. The need for a central system is supported by the Pensions Policy Institutes paper – ‘What needs to be considered when delivering a data-based research project involving multiple UK pension providers’, which highlights the importance of having a trusted 3rd party data aggregator.[footnote 16] We strongly welcome views on both approaches and we will look to explore this further with industry as we develop our policy further.

103. A central clearing house would be able to act as an independent organisation and a central point of contact for both sending and receiving schemes. This clearing house would be responsible for matching deferred pots, with a member’s chosen consolidator. It would also undertake communication with members where they have not previously chosen a consolidator. In cases where no active decision is made by the member, the clearing house would be responsible for allocating the member to one of the authorised consolidators.

104. This would be beneficial during the initial roll out, as without a central body communicating with members, there would be an increased risk of members being contacted by multiple schemes simultaneously and potentially choosing multiple consolidators. This approach could be vital in avoiding risks of confusing members with multiple communications, or a member ending up with multiple consolidators – a point some respondents to our call for evidence raised.

105. By introducing a clearing house, the aim would be to streamline the process and remove the administrative burden for pension schemes of matching pots, allowing the process to be more automated. The Pension Policy Institute’s report on how other countries have dealt with deferred small pots, noted that systems of transfer and consolidation are easier for employers to comply with when there is a large central platform, or a number of several connected platforms, with several countries are already using a clearing house or central data platform.[footnote 17] The clearing house would not be responsible for transferring funds, nor would it hold funds at any point – as the pot would remain invested with the ceding scheme until the point where the consolidator scheme was identified.

106. The government recognises that there are complications with creating a clearing house. These complications are chiefly twofold: additional investment that this would require and the potential for further complexity as a result of introducing a 3rd party into the transfer process.