Government response: Health is everyone’s business

Updated 4 October 2021

Government response to the consultation on proposals to reduce ill-health related job loss

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health and Social Care by Command of Her Majesty.

© Crown copyright 2021

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit The National Archives.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]

ISBN 978-1-5286-2363-6

CCS1120523008

CP 509

July 2021

Correction slip

Title

Health is everyone’s business

Government response to the consultation on proposals to reduce ill health related job loss

Session: 2021/2022

CP 509

ISBN: 978 -1-5286-2363-6

Correction

Text currently reads:

P.30 “Research conducted by the Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) during the early stages of the crisis showed over three quarters of NHS OH providers and more than half of in-house OH providers said their workloads had increased.47”

P.32 – “A survey by the Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) conducted in April 2020 showed three quarters of practitioners were spending an increased amount of time providing remote consultations”

Text should read:

P.30 “Research conducted by The At Work Partnership during the early stages of the crisis showed over three quarters of NHS OH providers and more than half of in-house OH providers said their workloads had increased.”

P.32 – “A survey by The At Work Partnership conducted in April 2020 showed three quarters of practitioners were spending an increased amount of time providing remote consultations”

Date of correction: 23 September 2021

Ministerial foreword

We are living and working longer than ever before. Being in work can help raise living standards, move people out of poverty and help reduce health inequalities. This not only benefits individuals and employers, through workforce retention, but also wider society, supporting our commitment to level up the country and enabling us to build back better.

The measures outlined in this response are designed to minimise the risk of ill-health related job loss through providing employers with access to good quality information and advice, supporting employers and employees during sickness absence, enabling Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to reap the benefits of Occupational Health (OH), and proposals to enable better use of the fit note. This is just one part of our approach to supporting disabled people and those with long-term health conditions. The ‘Health and Disability Support Green Paper’[footnote 1] led by DWP considers improvements to health and disability benefits in the short to medium term whilst also starting a discussion about more fundamental changes. Together these build on the commitments we made in ‘Improving Lives: the future of work, health and disability’,[footnote 2] including our ambition to see one million more disabled people in work by 2027. In addition, they complement the National Disability Strategy which sets out practical changes to improve disabled people’s everyday lives, helping to achieve equity of opportunities so that everyone can fully participate in the life of this country.

Disabled people and those with long-term health conditions remain under-represented in the labour market and there is significant variation in how employers manage work and health.[footnote 3] Before COVID-19, an estimated 300,000 disabled people fell out of work every year.[footnote 4] Society is missing out on their valuable contribution to the workforce, whilst individuals themselves are missing out on the health and financial benefits associated with good quality work.

While COVID-19 has brought significant economic challenges, with necessary economic restrictions leading to higher rates of redundancy and unemployment, we have also seen many employers harness the power of technology and introduce greater flexibility in the way work is done. Many employers have gone above and beyond in helping their employees juggle caring responsibilities, work flexibly and work from home throughout the pandemic.[footnote 5][footnote 6][footnote 7]

As the UK continues to recover and comes to better understand the longer-term impacts of COVID-19, it is more important than ever that disabled people and those with long-term health conditions are supported to remain in work so that no group is left behind. This government is committed to building back better, and providing the right support to disabled people and people with long-term health conditions will help create a healthier population with a higher level of employment that benefits productivity and drives the economy.

By working together to look after the health and prosperity of our people and our businesses, we champion not only the wellbeing of every individual in this country but also the nation as a whole.

Justin Tomlinson MP

Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work

Jo Churchill MP

Minister for Prevention, Public Health and Primary Care

Executive summary

In November 2017, we published ‘Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability’[footnote 8] which set out our plans to transform the employment prospects for disabled people and those with long-term health conditions over the next 10 years. In it, government set a goal to see a million more disabled people in work by 2027 and to realise an ambitious vision for society where ‘people understand and act positively upon the important relationship between health, work and disability’. Government continues to focus efforts across three key settings in order to achieve this: the welfare system, the workplace and the healthcare system.

‘Health is everyone’s business’ put forward a number of proposals to minimise the risk of ill-health related job loss through better workplace support for disabled people and those with long-term health conditions. It explored changes to Statutory Sick Pay, Occupational Health, information and advice, and employer guidance. The Health and Disability Support Green Paper[footnote 9] explores how to improve support for disabled people through the welfare system. Together, with the forthcoming National Disability Strategy, they are part of this government’s holistic approach to support disabled people and those with long-term health conditions to live full and independent lives.

Whilst this response focuses on the measures outlined in ‘Health is everyone’s business’, work beyond the scope of this response has continued at pace. For example, we have taken steps, along with local partners, to advance the work and health agenda, in particular in the area of prevention. We also want to ensure there is better integration between health and employment support services which will help people with long-term health conditions to enter and stay in work.

The majority of employers agree that there is a link between work and the health of their employees.[footnote 10] Employers who invest in the health and wellbeing of their workforce benefit from reduced sickness absence, increased productivity and improved workplace retention. Employees benefit from a supportive environment in which they can thrive and perform at their best. Being in work can help someone to be independent in the widest sense: by having purpose and self-esteem, by building relationships and by being financially independent.

As ‘Improving Lives’ set out, we want to see individuals, where appropriate, benefit from a preventative approach to ill-health and an environment which supports health promotion. We want to see employers creating healthier workplaces and offering the right support to their staff. We also want both employers and their staff to be supported by a health system which promotes good health and helps them to better manage their conditions. Much of the focus of this document is on the role employers themselves play, but we also recognise that when individual employees are struggling with health issues and engaging with the health system, there are opportunities to provide them with advice to help them manage the employment impact of their condition. To that end, we have:

- integrated Employment Advice provision in the NHS’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT) services in England[footnote 11]

- invested in Individual Placement and Support (IPS) with local partners, to test new ways of supporting people to enter, re-enter and stay in work

We have also worked with NHS England/Improvement and Public Health England to explore barriers and enablers to partnership working on work and health in local systems. We are currently undertaking further exploratory work on the development of partnerships, strategies and greater integration of services at a local level.

Impact of COVID-19

The consultation was published at a time when employment was at a near historic high and disabled people’s employment had also improved significantly; between October to December 2013 and October to December 2019, the number of working age disabled people in employment increased by 1.4m, from 3.0m to 4.4m.[footnote 12] It set out to build on that progress by introducing a comprehensive and balanced package of measures to support more disabled people and people with long-term health conditions to remain in work.[footnote 13] Since then, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been widely felt across the economy and society.

In response to the pandemic, government acted swiftly to protect the incomes of millions of people including through the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) and Self-Employed Income Support Scheme (SEISS).[footnote 14] This was followed by the Chancellor’s Plan for Jobs which set out to protect, support and create jobs. At Budget 2021, government announced the extension of the CJRS and SEISS alongside an additional £5bn for new Restart Grants and a new UK-wide Recovery Loan Scheme which will make available loans to help businesses of all sizes through the next stage of recovery. This combined economic response is one of the most comprehensive and generous in the world.

The pandemic also highlighted the important role that health professionals play in the work and health agenda. OH professionals, who provide expert advice and support on work and health issues, have played a critical role in supporting the response to COVID-19. For example, they have supported employers to provide advice on workplace adjustments, and supported individuals recovering from COVID-19 to return to work. Finally, we have taken a cross-government approach to considering and responding to the challenges to mental health and wellbeing presented by the pandemic, contributing to the COVID-19 Mental Health and Wellbeing Recovery Action Plan which was published 27 March 2021.[footnote 15] This is the government’s plan to prevent, mitigate and respond to the mental health impacts of the pandemic during 2021 and 2022.

The impact of the pandemic, including on the labour market and health of the nation, increases the need to progress the important shared agenda of work and health. The package of measures announced here reflects feedback from the consultation, while acknowledging the impact of COVID-19.

This balanced package of measures will enable and encourage employers to take greater responsibility for the health and wellbeing of their employees, by offering increased government support including through improved information and advice and access to OH provision.

Chapter 1 sets out how government will provide employers with access to good quality information and advice. Employers, and small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in particular, may lack the time, capacity or expertise to manage health events in the workplace, or to search for the most relevant guidance. Employers have told us that while they trust government advice in this area, the current information on offer is fragmented and not always easy to apply to real-world problems.

Respondents asked for better integrated advice and information that is easier to find and act upon. Government has improved guidance for employers and employees in response to the pandemic – including, on returning to workplaces safely. Government now intends to build on this by refining the information and advice given to employers on health, work and disability. This will be easy to navigate and readily usable, especially for SMEs.

Chapter 2 outlines government plans to support employers and employees during sickness absence. The majority of respondents agreed that statutory guidance should be strengthened, stating that clear guidelines would give employers more confidence to act and provide consistency in their approach. Government has therefore asked the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) to work with other arm’s length bodies (ALBs) to develop non-statutory guidance to support disabled people and people with long-term health conditions to remain in work, and on managing any related sickness absence. HSE will also explore introducing statutory guidance in this area.

Although respondents supported the intent of the proposal, there was concern that introducing a new right would risk undermining existing workplace protections, most notably the duty to make reasonable adjustments. In particular In light of feedback government has decided not to proceed with the consultation proposal to introduce a new ‘right to request work(place) modifications’ on health grounds but will instead take steps to increase awareness and understanding of existing workplace rights and responsibilities, in particular the duty to make reasonable adjustments under the Equality Act 2010, we heard concerns that a right to request workplace modifications may legitimise refusing requests for adjustments and detract from the positive duty on employers to make reasonable adjustments.

Chapter three covers Statutory Sick Pay (SSP). The consultation sought views on a range of measures related to Statutory Sick Pay. These measures sought to make the system more flexible, simple, and responsive. The pandemic has shone a light on the importance of SSP and over the last year government has made several changes to the system to support those who were self-isolating and unable to work as a result of COVID-19.

Government maintains that the pandemic was not the right time to introduce changes to the rate of SSP or its eligibility criteria. This would have placed an immediate and direct cost on employers at a time where most were struggling and could have put more jobs at risk. Government instead prioritised changes which could provide immediate financial support to individuals, including changes to the wider welfare system, the introduction of the Test and Trace Support Payment and wider economic support such as the Coronavirus Jobs Retention Scheme.

As we emerge from the pandemic, there is space to take a broader look at the role of SSP. Chapter three covers the feedback from respondents to the proposals in the consultation that covered SSP.

Chapter 4 outlines the steps that government is taking to enable SMEs and self-employed people to reap the benefits of expert health and work support including OH. This will be informed by learning from the innovations that have underpinned the health system’s response to the pandemic, with some evidence of increased demand for OH as more individuals adapt to new working environments and require support to return to work. The uptake of other measures outlined in this package is also likely to increase demand for OH. Small employers are five times less likely to invest in OH services than large employers.[footnote 16] Government will seek to address this by testing and evaluating the impact of a subsidy for SMEs and the self-employed, designed to reduce the cost of accessing suitable OH. The evidence and affordability of a subsidy, alongside developments in OH reform policies, will inform the case for a potential fixed term roll-out in the future.

More accessible OH services may lead to a rise in demand, and potential new customers of OH will require support to ensure they are not purchasing inappropriate or low-value services. Government will take action to improve information and guidance on purchasing OH and explore the potential of outcome-linked measures to support providers to improve and innovate, helping employers to choose the most appropriate services for their needs. This includes piloting outcome-linked metrics with OH providers and employers which could be used to support continual provider improvement and improve employer choice.

Government will work with the market to explore how it can support faster innovation in OH particularly in relation to innovative ideas that prioritise new OH service models and make greater use of technology, with the aim of increasing SME/self-employed purchasing of OH. Government is also committed to working with key delivery partners to explore the potential merits of a new Centre for Work and Health Research that could strengthen the research infrastructure that supports long-term innovation in OH.

The chapter concludes by addressing concerns over shortages in the OH workforce and details government plans to respond by considering methods to promote the expansion of clinical roles, improving OH multidisciplinary workforce models which capture both clinical and non-clinical roles, developing new training approaches and establishing an OH leadership function to help drive the OH workforce strategy.

Chapter 5 sets out other issues raised during the consultation which include insurance, tax, Access to Work and proposals to enable better use of the fit note, a key tool which can be used to support workplace conversations and returns to work. Although not in the consultation, many respondents took the opportunity to share views about how the fit note process could be improved. There was a general consensus that the fit note remains an important tool but should be reformed so that it better supports people to stay in and return to work. The launch of the Isolation Note in response to COVID-19 has demonstrated the flexibility and responsiveness of employers and the healthcare system through their acceptance and use of an alternative form of evidence. Government intends to build on this learning and continue to explore opportunities for digital transformation of medical evidence provision. Government is also exploring extending fit note certification to a wider group of healthcare professionals and introducing digital certifying of fit notes as well as looking towards further opportunities to make the fit note interactive. These changes will make the fit note a more effective tool in supporting healthcare professionals to deliver holistic health and work conversations that the government believes are essential in supporting their patients to remain in, or return to, work.

Some respondents highlighted the importance of insurance products as another way of supporting workers’ health and wellbeing. Government welcomes recent proposals from the industry body Group Risk Development (GRiD) to develop a ‘consensus statement’ which aims to enhance employer guidance, improve employers’ awareness of the link between good work and good health, and promote the use of expert-led support services. Government will continue to work with the industry to improve awareness among employers and self-employed people of the benefits that protection policies can provide.

Several larger organisations called for tax incentives. In response to early consultation feedback and to recognise the variable availability of welfare counselling, changes were made in the March 2020 Budget to enable employers to provide non-taxable counselling services. This includes related medical treatment, such as cognitive behavioural therapy. The changes took effect from April 2020.

A number of respondents commented on the valuable contribution Access to Work makes in supporting disabled people and those with long-term health conditions to receive adjustments to enter into and remain in employment, and told us they thought more could be done to promote the service among employers and individuals. Government continues to promote Access to Work as part of Disability Confident and is undertaking further marketing and promotion of the Access to Work programme.

An overview of the potential costs and benefits of the full policy package set out in this response is given in the Annex, along with the methodology of measuring these impacts.[footnote 17] It supports a balanced package of measures in which both government and employers go further to support health and wellbeing at – and through – work. It describes the costs and benefits to business, and the wider societal benefits the measures will bring.

Introduction

‘Health is everyone’s business’ set out a number of proposals to minimise the risk of ill-health related job loss. Prior to COVID-19, there were around 12.7m working-age people with a long-term health condition, including 7.6m disabled people whose condition reduces their ability to carry out day to day activities.[footnote 18] Over the course of a year, around 1.4m working-age people had at least one sickness absence lasting four weeks or longer.[footnote 19] The likelihood of a return to work reduces the longer the individual experiences sickness absence.[footnote 20] Disabled people were 10 times more likely to have a spell of long-term sickness absence (LTSA) and leave work following it than non-disabled people.[footnote 21] The research is clear. Early and sustained support by employers, including workplace adjustments, is an effective way to minimise the risk of ill-health related job loss. Employers agree there is a strong link between work and health; however, there is significant variation in the level of support offered by employers.[footnote 22][footnote 23] Those who have experienced incidences of disability or long-term sickness absence in their workforce are more likely to have support mechanisms in place; larger employers are more likely to have dedicated HR support as well as access to formal health and wellbeing services such as OH.

The Chancellor announced the Plan for Jobs 2020 as the second phase of the UK’s recovery from the pandemic. The plan builds on the £160 billion support package provided in the first phase by supporting, creating and protecting jobs across the UK. As well as supporting those who have lost their jobs, we need to continue to improve retention. COVID-19 has made the consultation’s aim of minimising the risk of ill-health related job loss even more important, as the UK continues to recover. Before the start of the pandemic, the general trend in disability employment had been positive since 2014, when comparable records began. The pandemic initially reversed these trends with the disability employment rate falling and the disability employment gap widening during the middle of 2020. The employment rates, for both disabled and non-disabled people are still below their pre-pandemic levels but the disability employment gap narrowed in late 2020/early 2021. For example, in the 12 months to March 2021 the disability employment rate decreased by 1.2 percentage points but the disability employment gap decreased by 0.2 percentage points. This suggests that the disability employment rate is not currently being disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.[footnote 24] Emerging evidence suggests that there has been a deterioration in people’s mental health, particularly disabled people’s mental health.[footnote 25] In addition, over half of those facing redundancy due to COVID-19 are either disabled or have a long-term health condition.[footnote 26] More widely, increased productivity through a healthier workforce supports the economic recovery whilst a healthier population also reduces pressure on both the health and welfare systems.

The measures government is taking forward provide greater clarity around employer/employee rights and responsibilities; recognise the important role of OH; and reinforce the need for employers to have access to clear and compelling information and advice that is easy to understand, authoritative and accessible.

These measures support the government’s ambition to see one million more disabled people in work by 2027 and build on commitments made in ‘Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability’.[footnote 27] This work will also complement the Health and Disability Support Green Paper, which focuses on improving employment support and enabling independent living, and the National Disability Strategy which will address broader issues which can unfairly limit opportunities for disabled people, alongside recent action announced by government to tackle obesity and help people live healthier lives.

The challenge cannot be solved easily or quickly, but by working with employers and healthcare professionals together we can start building a system that better supports disabled people and those with long-term health conditions to remain in work.

This document forms the government’s response to the ‘Health is everyone’s business’ consultation. It provides an overview of the responses received and provides details of what government intends to do next to take forward the package of measures.

How we consulted

The government launched the consultation ‘Health is everyone’s business’ on 15 July 2019. The consultation closed on 7 October 2019. The consultation was hosted online, accessible via GOV.UK. In total, 485 responses were submitted electronically. Table 1 shows a breakdown by respondent type. The majority of responses came from individuals and employers (or their representatives), followed by charities, healthcare professionals and trade unions.

Table 1: Responses to ‘Health is everyone’s business’ by respondent type

| Respondent Type | Responses | % |

|---|---|---|

| Employer | 88 | 18% |

| Employer Representative | 46 | 9% |

| Charity | 47 | 10% |

| Trade Union | 17 | 4% |

| Occupational Health Provider | 35 | 7% |

| Health Service Provider | 23 | 5% |

| Self-Employed | 16 | 3% |

| Individual | 111 | 23% |

| Other | 102 | 21% |

| Total | 485 | 100% |

As Figure 1 demonstrates, of those employers who responded, the majority were large employers (43%), followed by small (23%) and medium sized employers (23%) and finally micro-employers (12%). Broken down by industry, the majority of respondents said they provided ‘other services’ (37%), followed by ‘public admin, education and health’ (29%) and construction (9%). Respondents classifying themselves as ‘other services’ included a wide range of organisations and individuals, including membership associations, insurance providers, professional bodies, patients, employees and unemployed people.

Figure 1: Charts illustrating employer responses by size and type

| Size | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Micro (0-9 employees) | 12% |

| Small (10-49 employees) | 23% |

| Medium (50-249 employees) | 23% |

| Large (250+ employees) | 43% |

| Sector | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Private | 63% |

| Public | 23% |

| Voluntary | 14% |

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| North East | 7% |

| North West | 11% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 7% |

| East Midlands | 8% |

| West Midlands | 9% |

| East of England | 8% |

| London | 11% |

| South East | 13% |

| South West | 8% |

| Wales | 7% |

| Scotland | 7% |

| Northern Ireland | 3% |

| Industry | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 1% |

| Energy and water | 1% |

| Manufacturing | 7% |

| Construction | 9% |

| Distribution, hotels and restaurants | 4% |

| Transport and communication | 7% |

| Banking and finance | 4% |

| Public admin, education and health | 29% |

| Other services | 37% |

In addition to the responses received via the online portal, some responses were submitted separately by stakeholder organisations. These responses provided comment on the package of measures as a whole or individual policy areas relevant to the stakeholder organisation, rather than responses that followed the ordering of questions included in the consultation document.

Government also hosted 12 roundtable events across the UK to promote engagement with the consultation, as well as 6 insight groups focusing on specific policy areas. These insight groups considered the right to request workplace modifications, SSP and OH.

Finally, government received 772 responses from Mind, the mental health charity, which distributed specific consultation questions to its membership base and invited members to respond.

Across these different sources, the responses received were comprehensive and rich in detail. The consideration respondents exhibited has enabled government to understand both the broad trends and nuanced comments underpinning consultation feedback.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic government took additional time to consider responses to ensure the package of measures being proposed remained relevant in a post-COVID-19 landscape. Government is confident that this package of measures is more relevant than ever.

Chapter 1 outlines our plans to support employers to navigate the work and health landscape. Chapter 2 outlines our plans to support employers and employees during sickness absence. Chapter 3 outlines responses to the consultation on SSP reforms. Chapter 4 outlines our plans to help employers deal with cases where they need additional high-quality OH support. Finally, Chapter 5 concerns other issues raised during the consultation, including enabling better use of the fit note, the role of insurance, tax and Access to Work (AtW).

Chapter 1: Helping employers navigate the work and health landscape and make better use of existing tools

This government wants employers and employees to have better interactions about work and health to support employee retention. We want to mitigate any adverse effects of the pandemic (whether direct or indirect) on disabled people or people with long-term health conditions.

Both employers and employees told us that navigating the variety of sources of publicly-funded advice and information on work and health is confusing. Government heard that providing easily-accessible information and advice is important, as some employers report lacking confidence and being afraid of ‘doing the wrong thing’. This is particularly true for SMEs, many of whom do not have access to dedicated HR support and/or in-house OH (see Chapter 4). [footnote 28]

Government also heard that there is a lack of awareness and understanding of rights and responsibilities under the Equality Act among both employers and employees, in particular around providing reasonable adjustments.[footnote 29]

It is vital that employers (including the self-employed) have access to the right tools and information to enable them to effectively support their employees and reduce the risk of people falling out of work in the long term.

Recognising what employers need

Employers have an important role to play in creating healthy and inclusive workplaces, but often lack the time, resources or expertise to take the right steps (especially among SMEs).[footnote 30][footnote 31] This exposes employers to legal and reputational risks, productivity losses and increased costs. Some recruitment practices mean that disabled candidates or applicants with long-term health conditions don’t always get fair consideration. Existing employees do not always get the support they need to stay in work. This contributes to the lower rates of employment for disabled people and the wider problem of health-related job loss, some of which could be prevented.

COVID-19 has shone a light on a range of health-related issues that preceded the pandemic. Navigating the challenges raised by COVID-19, and the changes this brings to the management of health in every workplace, has increased employers’ information needs. These include how to support flexible/home working, how to support people with long-term health conditions (including mental health conditions) in the workforce, how to manage returns to work and how to ensure that workplaces are safe. Government has already issued clear guidance documents to help employers adapt, including the suite of ‘Working safely during Coronavirus’ guides aimed at different types of work.

While employers see central government as the most reliable information source, they report that the current information offer is fragmented, hard to navigate and difficult to apply in practice. They want support that helps them to solve real-world problems. Research shows that providing better information and advice can improve take-up of health and wellbeing initiatives amongst SMEs.[footnote 32]

A stronger information offer for employers will underpin and support the other elements of the consultation package, as well as existing government support and advice (including Disability Confident, SSP and other related content ‘owned’ by ALBs and other Departments). Without this, take-up of other consultation measures is likely to be limited and it will be difficult to realise their potential benefits in full.

Improving the offer

The government proposed to improve the provision of advice and information to support management of health in the workplace and encourage better-informed purchasing of expert-led OH advice (see Chapter 4 for more details on the latter).

Government heard that although employers access the internet, they experience navigation issues when searching for information on health in the workplace, and also aren’t sure what information they can trust. They want information that is good quality, easily accessible and in one place.

Government’s online information is the preferred starting point for many employers, in particular SMEs. Employers said they trusted government advice and guidance more than other information sources. They were supportive of a one-stop government information service where resources were better integrated.

Many employers stated they require more information, advice or guidance on dealing with disability and long-term health conditions. There was a strong consensus for better quality and more accessible information.

Consultation responses also underlined the importance of providing locally focused information and using local networks to support employers. A number of projects and trials have been running across DWP and other Departments, as well as external to government, to research and identify how we can most effectively meet these needs.

What government intends to do next

Government will ensure that better integrated health and disability-related information for employers is made accessible. We will:

- continue collaboration between teams producing content in different parts of government and across ALBs to enhance resources to support COVID-19 returns to work/workplaces

- develop a national information and advice service for employers on health, work and disability, with material designed to help manage common health and disability events in the workplace. This will be developed with the needs of SMEs in mind

On the proposal for a national information and advice service, government has been working with employers to understand their needs. This is informing design work during 2021.

Chapter 2: Helping employers improve support for employees during sickness absence and return to work

Government plans to help employers navigate the work and health landscape, make better use of existing tools and equip them with the right information and advice to support employees’ needs which should inform better interactions around work and health. In many cases these good conversations between employers and employees will facilitate an employee remaining in (and returning to) work.

However, it is not always the case that employees receive the support they need from employers. That is why government considered proposals aimed at helping all employers understand what they should do to support employees when sickness absence happens. This chapter covers the importance of workplace adjustments and proposals to strengthen statutory guidance to encourage early and supportive action from employers.

Concerns have been raised that COVID-19 has exacerbated some of the existing issues around work(place) adjustments that were highlighted by consultation respondents, specifically around awareness, understanding and compliance. There are reports that the large number of people working differently has led to some employees not receiving adjustments in new work settings, for example when working from home, and that some employers lack the knowledge needed to provide them in this new context. With emerging evidence from early on in lockdown suggesting a marked increase in the number of employees with worse symptoms of musculoskeletal pain, higher levels of fatigue, poor sleep, and higher levels of eye strain, the number of people who are entitled to – or would benefit from – work(place) adjustments could be increasing.[footnote 33]

The importance of adjustments

As the consultation set out, effective work(place) modifications and adjustments (for example, changes to the working environment, hours and tasks, as well as phased returns to work) can reduce the length of sickness absence and help employees remain in work. The consultation sought views on whether to introduce a right to request work(place) modifications on health grounds in order to increase the number of people able to benefit from such modifications and adjustments. It also sought views on how this might be implemented. The consultation also made clear that the introduction of this new right was not intended to have any adverse impact on the existing duty to make reasonable adjustments for disabled people under the Equality Act 2010.

Overall, consultation responses agreed that a new right could be an effective way to help employees; however, respondents also raised significant concerns which broadly broke down into the following main themes:

Lack of awareness and understanding

Government heard that there is a lack of awareness and understanding among employers and employees around their existing rights and responsibilities. Specifically, there were particular issues around the definition of ‘disability’ and concerns that individuals may not be aware of what they are entitled to under the act. Disagreement between employers and employees over whether or not an individual is covered by the act was raised.

Government also heard that employers may struggle to identify appropriate adjustments and what constitutes ‘reasonable’ under the duty to make reasonable adjustments. This was highlighted as an area of particular concern for SMEs.

A number of responses therefore urged government to do more to increase awareness and understanding of existing rights and responsibilities in this area, either in addition to or instead of introducing additional legislation. For example, one respondent suggested implementing awareness campaigns to educate employers and employees.

Mental health was raised by a number of respondents as an area requiring greater awareness and understanding. Some respondents proposed changing the definition of disability in the Equality Act to better support those with mental health and fluctuating conditions.

Risk of greater confusion

A number of responses expressed concern that introducing a new right to request work(place) modifications on health grounds risked causing greater confusion among employers and employees in what is deemed an already complex area. There was general concern that introducing new legislation in this area would risk ‘muddying the waters’.

Risk of undermining existing workplace protections

A lot of responses raised concerns that introducing a new right to request work(place) modifications on health grounds could risk undermining existing workplace protections, in particular the duty to make reasonable adjustments for disabled people. Respondents were concerned that in practice, introducing the new right may lead to employers shifting focus from their positive duty (to make reasonable adjustments) to the worker’s right to request work(place) modifications.

Others highlighted the risk of employees who are unaware of their statutory rights under the act being less likely to receive reasonable adjustments as a result of lack of knowledge or being influenced by employers. There was particular concern amongst some respondents that a new right could legitimise refusing a request under the act and might limit the ability of disabled employees to seek the reasonable adjustments to which they are legally entitled.

Compliance

Government heard there are issues with the way in which some employers approach the legislation, with some respondents citing examples of employers creating organisational barriers for disabled employees to access their rights. They also indicated employers are more likely to make reasonable adjustments for those employees that are more ‘valued’ to the business. A number of respondents stated that the intent of our proposal would be better achieved through strengthening existing protections under the act.

What government intends to do next

Given the risks identified of introducing new legislation in this space and feedback on the issues with the existing framework, on balance, government has decided not to proceed with the introduction of the proposed right to request work(place) modifications at this stage. However, there is a strong case to consider what more could be done to raise awareness and understanding among employers and employees of their existing rights and responsibilities, in relation to both the duty to make reasonable adjustments and work(place) adjustments more broadly.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) is the enforcer of the Equality Act, which includes the reasonable adjustments duty. It undertakes strategic litigation and enforcement to challenge flagrant, systemic and egregious breaches, or to clarify the law. The Commission is resourced to undertake strategic enforcement of EA10 (so individuals will usually need to make an Employment Tribunal claim to challenge a failure to make reasonable adjustments).

The EHRC produces guidance and resources for employers, service providers and other duty bearers to encourage compliance. It has introduced additional guidance for employers on how reasonable adjustments should be made during the COVID-19 pandemic, including several examples of specific adjustments to encourage good practice. The government will continue to support and fund the Equality Advisory and Support Service (EASS), the helpline which provides free bespoke advice and in-depth support to individuals with discrimination concerns. The EASS has the ability to intervene on an individual’s behalf to help resolve an issue, including in relation to reasonable adjustments at work, and can provide advice on whether a person is likely to meet the Equality Act’s definition of disability. The EASS can also advise people who wish to take their complaint further on their options.

Access to Work (AtW) may also provide funding to meet additional employment costs resulting from an individual’s disability (or long-term health condition) that are over and above those that may be considered reasonable under an employer’s duty to make reasonable adjustments.

Moving forward, Chapter 1 outlines our plans for better-integrated health and disability-related information and advice for employers, which will include material designed to help employers manage common health and disability events in the workplace. This will in particular be useful for SMEs, who often do not have dedicated HR functions.

Chapter 5 discusses Access to Work (AtW). AtW recognises the need to raise the visibility of the support it offers and is working to expand its reach by proactively raising awareness of AtW with disabled people, those with long-term health conditions and employers. This has included a communication campaign and social media activity.

DWP is working to transform AtW to deliver a modern, streamlined service that provides an improved customer experience. This includes introducing a new digital customer journey that will deliver a quicker and more efficient service. To enable disabled people to have greater flexibility to work from more than one location, AtW has introduced a new flexible offer to respond to the challenges of Covid-19, and to support disabled people to take up opportunities. Building on this flexibility and to support transitions into employment, AtW is piloting a new Adjustments Passport for young people who are transitioning from education to work, veterans leaving the armed forces, and freelancers and contractors moving between job roles.

Alongside our contribution to the COVID-19 Mental Health and Wellbeing Recovery Action Plan, we will continue to support the business-led work with the Thriving at Work Leadership Council, to promote best practice and guidance offered via the Mental Health at Work online gateway. This hosts over 400 resources to inform and advise employers on managing mental health in the workplace.

In addition, flexible working has the potential to help improve retention of staff who may otherwise fall out of work due to a (temporary or permanent) change in their health. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is taking forward the 2019 Conservative Party manifesto commitment to encourage flexible working and to consult on making it the default unless employers have good reasons not to. The consultation will be published in due course.

These steps, as well as wider measures outlined in this response, including our plans to improve access to OH outlined in Chapter 4, will help encourage more adjustments to be made for disabled people and those with long-term health conditions and help improve compliance with the reasonable adjustments duty. This will help people to either stay in work or return to work following sickness absence. Government will continue to work across departments and with external stakeholders, including the EHRC, to consider other ways to raise awareness and understanding among employers and employees.

Strengthening guidance to encourage early and supportive action from employers

In 2018 around 1.4 million people experienced LTSA, defined as a leave of absence for four or more weeks, resulting in over 100,000 people falling out of work. Of these, 25,000 fell out within the first six weeks.[footnote 34] We know that early intervention and support during sickness absence is important and that a lack of support from an employer can be a key factor in prolonging sickness absence.[footnote 35][footnote 36]

Although research suggests that the majority of employers reported putting measures in place to manage their employees’ return to work following a LTSA, this is not universal (e.g. 79% had used regular meetings and 69% had developed return to work plans).[footnote 37] There were also differences between large and small employers, with large employers being more likely to report adopting a wider variety of measures. Evidence also suggests that some individuals may be dismissed instead of effort being made to support them back into the workplace.[footnote 38]

COVID-19 has further highlighted the importance of maintaining best practice, with lockdown measures having a potentially significant impact on health and wellbeing.[footnote 39] Early research suggests that the sudden changes to homeworking due to the pandemic has contributed to an increase in musculoskeletal conditions and poor mental health for some employees, especially among those in less frequent contact with their employer and also younger workers.[footnote 40]

The consultation asked whether statutory guidance should be strengthened to encourage employers to take appropriate steps to support a person on sickness absence to return to work, and sought to establish whether this guidance should be principle-based or set out specific actions for employers to take.

The majority of respondents agreed that statutory guidance should be strengthened, stating that clear guidelines would give employers more confidence to act and provide consistency in their approach. Of those who did not agree, government heard concerns over increased business burdens and reduced flexibility, should the statutory guidance be too prescriptive. Respondents who said ‘maybe’ agreed to strengthened statutory guidance providing the guidance acknowledged individual circumstances and recognised that employees should be given an appropriate amount of time to recover before actively engaging in a return to work.

A prescriptive vs. principle-based approach

The majority called for a combined approach: broad statutory principles supported by non-statutory detailed information and case studies for those who may need additional support.

Responses suggested the majority of large employers have processes in place for sickness absence management. However smaller employers are less likely to have these processes and therefore struggle when sickness absence occurs. To overcome this, smaller businesses were more likely to prefer prescriptive guidance on what actions to take to support an employee returning to work following sickness absence, to help avoid mistakes and potential grievances against them. However, concerns were raised that a heavily prescriptive approach could inadvertently create a ‘tick list’ to dismissal.

Government also heard that strengthened guidance combined with clear principles will offer transparency on what should be expected during sickness absence, both from the employer and the employee. However, this should not be unduly prescriptive and should not cut across the collaboration needed between employers and employees to respond to the individual set of circumstances.

Consistency in engagement

A common theme emerged from employees around a lack of consistency with the support they received and the documentation of key meetings and actions. Similarly, employers noted the same issues with consistency and called for better quality and more accessible advice to help them provide a consistent approach and meet legal requirements.

Responses also highlighted the importance of employee engagement. Equal weight was given to identifying barriers, agreeing return to work plans and engaging with OH services, suggesting that the more collaborative the approach between the employee and employer, the greater the likelihood of agreeing appropriate next steps to aid a more sustainable return to work.

What government intends to do next

Government recognises that employers need more clarity on their existing responsibilities and clearer information to enable them to support disabled people and those with long-term health conditions to remain in work or return to work following sickness absence.

Therefore, Government has asked the HSE to explore ways to strengthen guidance on how employers can best support disabled people and those with long-term health conditions to remain in work, and on managing related sickness absence. HSE already provide a range of expert advice to support employers in the area of health and work, including preventing and managing work-related stress and musculoskeletal disorders: two of the leading causes of sickness absence.[footnote 41]

Supporting disabled people and those with long-term health conditions to remain in work and managing any related sickness absence requires a collaborative approach across government. As a first step, working with other ALBs, HSE will strengthen existing non-statutory guidance before exploring the introduction of statutory guidance.

Government recognises that employers report barriers to supporting employees to return to work following sickness absence. Small employers in particular report a lack of time or staff resources and capital to invest in support. Existing government schemes such as Disability Confident and Access to Work can help employers to support disabled employees and those with long-term health conditions. In addition, employers can draw on the expertise of the existing OH market which can help individuals’ return to work and reduce unnecessary sickness absence. The measures outlined in this consultation response build on this support.

In particular, our plans for a national information and advice service for employers on health, work and disability; OH market reform, including increasing access for SMEs; and changes to the fit note to encourage better work and health conversations will help employers adhere to the key principles of the guidance.

Chapter 3: Statutory Sick Pay

The consultation sought views on reforming SSP so that it is available to all employees that need it, more flexible in supporting returns to work, and underpinned by a suitable enforcement framework. In response to COVID-19, government has introduced a series of unprecedented measures to ensure that individuals and businesses have access to the support they needed. Access to SSP has been a key part of this response. Government extended eligibility of SSP to employees who were self-isolating in line with public health advice, ensuring that eligible employees were not without this financial protection. We also introduced the Coronavirus Statutory Sick Pay Rebate Scheme, which supports small and medium sized businesses throughout the country to manage the increased costs of covid-related absences, and we temporarily suspended waiting days which made SSP payable from the first day of a coronavirus-related sickness absence.[footnote 42]

Phased returns to work: enabling flexibility

The consultation outlined the benefits of phased returns to work which have been shown to reduce the likelihood of an individual falling out of work and increase the time spent at work in the long-term. They have been shown to be particularly effective in supporting individuals with musculoskeletal and mental health conditions, which are the most common health conditions of disabled people both in and out of work.[footnote 43][footnote 44]

Under the current rules, SSP does not allow for phased returns. Payment of SSP stops when an employee returns to work, even if they return on reduced hours. This can deter employers from offering phased returns and employees accepting them. Respondents were broadly supportive of phased returns to work. There was unequivocal support for clear information and guidance on phased returns, including in relation to implementation across settings and examples of scenarios in which a phased return could be beneficial.

Respondents were supportive of more guidance from healthcare professionals, for example via the fit note. The “maybe fit” section on the fit note, which includes the option of a phased return, is currently underutilised by GPs, with only 7% of fit notes referencing this option.

The Lower Earnings Limit

Employees who earn less than the Lower Earnings Limit (LEL), which is currently £120 per week, do not qualify for SSP. This includes those who have multiple jobs which are each paid below the LEL. Government did not extend SSP to employees below the LEL as part of its response to the pandemic. Extending SSP in this way would not have been the most efficient way to support these employees and would have placed an immediate cost on employers at a time where most required government support. The most effective way of getting financial support to these individuals was through the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme and the existing benefits system. As part of the response to the pandemic, government took steps to strengthen the safety net including through increases to Universal Credit.

The consultation asked whether respondents agreed that SSP should be extended to employees earning below the LEL and views on the rate that should be extended to this group. A majority of respondents (75%) agreed that SSP should be extended to employees earning below the LEL. This measure was supported by small and large employer respondents alike. Respondents felt that by extending SSP to those earning below the LEL, employers would be better incentivised to reduce sickness absence for all of their employees.

Supporting SMEs with the cost of sickness

It is important that sick pay is paid by the employer in order to ensure there remains a strong link to the workplace and to incentivise the employer to support a return to work. The consultation acknowledged that SMEs may be less likely to have the financial and human resources to invest in health and wellbeing initiatives such as occupational health provision. Despite this, many SMEs already adopt good practice measures such as phased returns to work following absence.[footnote 45]

In response to COVID-19, government introduced a temporary rebate to support SMEs with the increasing cost of absence as significantly more employees were required to take sickness leave in line with public health guidance. This rebate was focussed on supporting SMEs with the costs of increased absence caused by periods of self-isolation, rather than driving better management of absence. Take up of the scheme has been lower than initially forecast.

The consultation sought views on how a permanent rebate could support employers to manage the cost of sickness absence and encourage best practice. Responses to this were mixed. Most who favoured a rebate supported ease of access over any attachment of conditions, whereas others suggested that a rebate should be linked to outcomes such as a return to work. A key concern from respondents was that this sort of conditionality could lead to perverse incentives for employers to bring employees back to work before they were ready. Respondents felt that linking a rebate to a code of practice or other guidelines would result in a ‘tick box’ exercise and lead employers to adopt the minimum standards required to qualify for a rebate rather than innovating to reduce sickness absence.

Enforcement

An effective enforcement system is vital to creating a level playing field for business and employees alike. There are indications that some employees are not receiving SSP when they are entitled to it, but instead relying on welfare benefits. Respondents felt that government should be taking a more robust approach to enforcement and cracking down on employers who fail to meet their obligations. The majority (72%) agreed that there was a need to introduce better enforcement of SSP.

Government remains committed to the development of a Single Enforcement Body which will bring together existing enforcement bodies into a single and recognisable organisation. The Body will protect workers across the country and help to provide a level playing field for the majority of employers who respect the law. As part of the consultation response on the Single Enforcement Body, government confirmed its intention to include enforcement of SSP within the Body.

A consistent theme throughout the consultation response was a need to not penalise employers who had made genuine mistakes. In practice, it can be difficult to establish whether a genuine mistake has been made and so enforcement should take a proportionate approach with a focus on rectifying the problem and supporting future compliance.

Next steps

The consultation posed several important questions on the future of SSP which require further consideration.

Government maintains that SSP provides an important link between the employee and employer but that now is not the right time to introduce changes to the sick pay system.

Chapter 4: Helping employers access quality Occupational Health (OH) support

Expert support such as OH services can be a critical component in helping individuals remain in and return to work, reducing unnecessary sickness absence, increasing productivity and enabling individuals to live better for longer. In this document where we refer to OH services we include services that can help to achieve these (and other relevant) outcomes and reduce ill-health related job loss. These can include fitness for work assessments, health surveillance, advice on return to work and reasonable adjustments, vocational rehabilitation, case management, biopsychosocial approaches[footnote 46], health and wellbeing services and signposting to services that treat specific conditions. While in many cases action such as better work-focused conversations between the employer and employee is enough to support job retention (see Chapter 1), in others, additional high-quality support is required to prevent people falling out of work.

Government believes OH has an important role to play in supporting job retention, and enabling staff to thrive in work. This has been underlined by the role that OH services have played in the COVID-19 recovery, supporting returns to work. Research conducted by the Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) during the early stages of the crisis showed over three quarters of NHS OH providers and more than half of in-house OH providers said their workloads had increased.[footnote 47]

However, there is a wide variation in access to OH services. Large employers are five times more likely to offer OH than small employers.[footnote 48] While employees for small employers are less likely to have long-term sickness absences than employees of large employers, disabled people working for small employers are more likely to lose their job, as the gap in job retention rates between disabled and non-disabled people is bigger in small employers than large employers.[footnote 49] Over a third of employers who do not access OH services cite cost as the main barrier, but knowledge of actual costs amongst small employers is limited[footnote 50] and some employers without access have a lack of understanding, or have not fully considered the benefits, of OH services.[footnote 51] Some see OH services as relevant only to those who have to deal with long-term sickness absences or disabled employees or those with health conditions, and sometimes as a means for managing people out of organisations.[footnote 52] Government research indicates that both providing financial incentives and/or providing advice in the form of a needs assessment and signposting could increase SME take-up of health and wellbeing services such as OH.[footnote 53]

One of the aims of the new information and advice service in Chapter 1 is to ensure all employers are better aware of the broader benefits of OH for all employees and their productivity, as opposed to just those experiencing sickness absence or with a long-term health condition or disability. However, increasing employer awareness and understanding of OH alone is not enough.

‘Health is everyone’s business’ identified several issues in the commercial OH market, which currently delivers the majority of OH services. These included: cost as a key barrier to procuring OH; shortages in the OH workforce, particularly clinical staff, which risk the future capacity of the OH providers to deliver services; potential for more rapid innovation particularly targeted at SMEs and self-employed people; and a lack of awareness/understanding of the full range of OH services.

The measures outlined in this chapter form a strategy for reforming the OH landscape of provision, both to increase demand for OH and address these issues. This strategy, combined with the measures outlined earlier in this response – including improvements to information and advice (Chapter 1) and encouraging and supporting employers to take early action to support employees (Chapter 2) – will support development of a market that has the capacity and capability to respond to increased demand, particularly in light of COVID-19.

The impact of COVID-19 on the OH market

Alongside analysing responses, government has carefully considered how COVID-19 has affected the OH market.

An independent market forecast predicts the ‘new normal’ will present opportunities for the OH sector from 2021 onwards. These could result from the need for employers to be more proactive in managing health in the workplace and employees exhibiting greater concern over their health and safety at work. Technological OH developments are forecast to be crucial for penetrating the SME market and ensuring OH services can reach employees working remotely.[footnote 54]

A survey by the Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) conducted in April 2020 showed three quarters of practitioners were spending an increased amount of time providing remote consultations – via both telephone and video software such as Zoom/Skype – with almost all respondents reporting a decrease in face-to-face work, reflecting behavioural changes evident across workplaces during the pandemic.[footnote 55]

Recent research commissioned by DWP also showed up to an additional 8% of businesses newly purchased OH during the pandemic specifically to help them deal with COVID-19-related OH issues.[footnote 56]

Evidence has shown the challenges businesses continue to face in achieving pre-COVID-19 growth and revenue levels. A survey conducted by the Bank of England shows that in Q4 2020, businesses’ sales, employment and investment levels were lower than expected in the absence of COVID-19, and that businesses do not anticipate investment to recover until at least 2022. The survey also found that implementing measures to control the spread of COVID-19 were expected to increase costs of running the business.[footnote 57]

The pandemic has made the proposed strategy for reforming the commercial OH market more important than ever. The strategy outlined in this chapter will help improve employer access to relevant OH services, by: testing a potential new OH subsidy to help tackle financial barriers to purchasing OH; supporting the development of innovative OH services which may improve access for those currently less likely to purchase OH (meaning SMEs and self-employed people); developing the infrastructure to support continuous research and development in OH; driving continuous quality improvement in the market; providing access to procuring support that can help employers purchase relevant quality services that meet their needs; and addressing capacity issues in the OH workforce to ensure a range of specialities are available in the long term to serve the anticipated increase in health conditions post-COVID-19.

A potential new OH subsidy

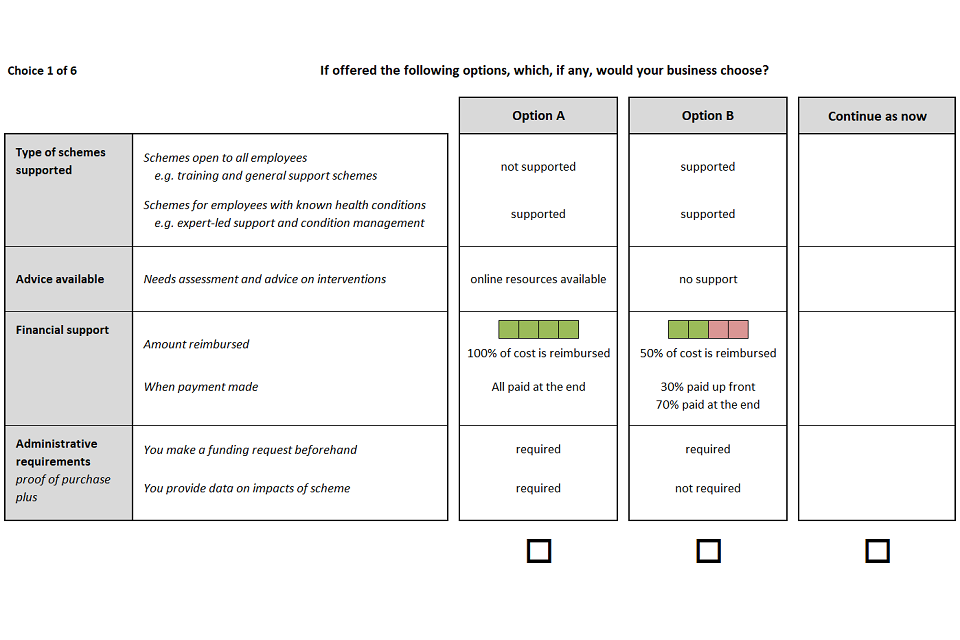

The consultation sought views on whether a targeted financial incentive would help SMEs and self-employed people to overcome barriers to accessing OH. Views were also sought on how this might be administered and what services should be prioritised under a subsidy. A subsidy would aim to:

- increase access to OH services by reducing purchasing cost for SMEs and self-employed people, targeting those least likely to have access

- encourage more employers to take a proactive approach in supporting health in work and to purchase OH through the commercial market

- support the growth of a dynamic independent sector to stimulate more affordable offers for SMEs and the self-employed

Overall, a majority of respondents were in favour of a subsidy for SMEs and the self-employed to increase access to OH. Employers being asked to contribute part of the cost was thought necessary to ensure their commitment and to protect against exploitation of the scheme. Only a few respondents were directly opposed to the proposal and expressed opinions that OH should be free, or should form part of NHS care. Some respondents highlighted the importance of a subsidy being easy to access and drew attention to the impact on business of administrative processes as well as the availability of OH services.

The consultation sought views on giving the smallest SMEs and self-employed people the largest subsidy. Most respondents favoured this approach, with others undecided and a small number opposed. Respondents expressed views that eligibility should be means tested or based on turnover, a uniform entitlement would be simpler, and tax incentives would be more inclusive of all employers.

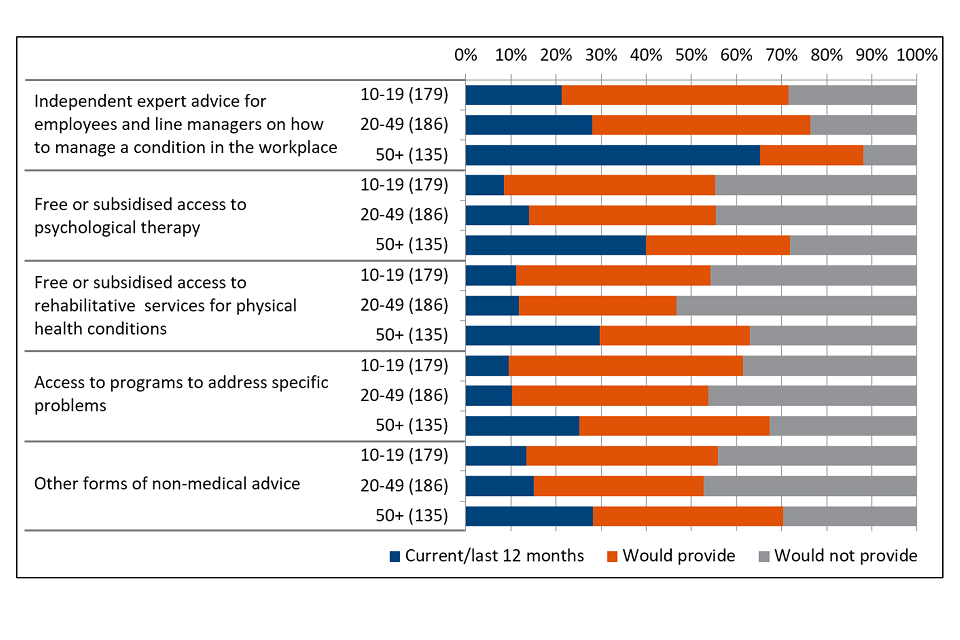

The consultation asked what type of OH services should be prioritised by any subsidy. Advice and assessments were most often the first priority, well ahead of training and capability of managers and businesses provided by OH professionals, and OH recommended treatments. However, treatments were often the second highest priority, showing they are still highly valued.

Consultation views and feedback from the Occupational Health Expert Group (OHEG) suggested government should look beyond traditional OH medicine to include other tools that would also help employers retain employees with disabilities and long-term health conditions, such as vocational rehabilitation and case management.

The consultation sought views on measures to ensure subsidised services were of sufficient quality. The most common proposals were to ensure that providers are registered or accredited, such as signed up to a regulatory body, and to have an approval identifier such as a licence or membership of an independent accreditation scheme such as Safe, Effective, Quality Occupational Health Service (SEQOHS). Respondents also mentioned that there should be a feedback mechanism and emphasised the importance of having access to a wide range of providers.

Government believes linking quality requirements to a provider’s eligibility to deliver subsidised services could incentivise providers to continue to offer a good standard of service, and support quality improvement in the market. Responses from OH providers expressed mixed views about how demanding these requirements should be.

Some providers suggested that a subsidy should be underpinned by registration or accreditation schemes, whilst others favoured ‘lighter touch’ options such as an audit process, a benchmark or standards indicator, a national register of minimum requirements, or a government approved list of providers.

There is evidence of self-regulation amongst providers, with almost all OH providers agreeing that the training, development and/or accreditation systems they had in place were effective in ensuring quality of service.[footnote 58] Further detail on proposals specifically related to quality and buying support are included below.

What government intends to do next

Government will test a subsidy which would aim to gather evidence on whether targeted financial incentives improve access to OH and employment outcomes. This test will be robustly evaluated and findings, alongside developments in OH reform policies, and affordability, will inform the case for potential fixed term roll-out in the future. Government will work with experts to ensure minimum qualification criteria are in place that OH providers should meet in order to be able to deliver subsidised services, and will assess provider suitability criteria as part of the subsidy test.

These criteria should balance the need for employers to have confidence in the services they are procuring, with the importance of ensuring sufficient choice is available in the market and that innovative practice is encouraged.

The aim would be to coordinate testing to align with developments in employer information and advice as well as wider OH market initiatives to develop buying support and innovation.

Government has met with OH experts and reviewed evidence from the Fit for Work programme to consider how best to design and deliver a subsidy test that is effective and does not impose unnecessary administrative burden on employers.

Government is continuing discussions with representatives of the insurance sector, which will help in understanding the different routes through which employers may prefer to access OH services.

Quality and buying support

The consultation package aims to encourage many more of the smallest employers and the self-employed to use OH. Many such employers will have no awareness or experience of procuring or using OH. There is limited guidance targeted at SMEs and self-employed people that either makes the case for OH or provides advice about when and how to procure it effectively. This increases the risk that they will purchase inappropriate or poor value services, or decide against procuring OH at all.

There is also a need to improve the knowledge of purchasers in ways that will encourage the market to compete (on both price and effectiveness of service), while ensuring continual development and provision of good quality, cost-effective services, especially for the SME sector.[footnote 59]

The consultation set out proposals to improve the advice and information support, both at national and local level, for employers (especially SMEs and self-employed people) on workplace health and wellbeing. This included improving access to information, such as on how and where to access OH services, which could improve employers’ confidence in purchasing expert-led work and health services.[footnote 60][footnote 61] This guidance should be relevant and user-friendly, especially for SMEs, in order to improve employers’ confidence in dealing with health-related work issues.

The consultation also discussed proposals to encourage standards and indicators of quality, including ones which focus on the quality and cost effectiveness of the services that employers receive.

Improving buying support

The consultation asked what additional information employers would find useful when purchasing, or considering purchasing, OH. Respondents were generally supportive of the need to improve the buying support available. Employers (of all sizes) supported a range of measures. From most popular option to least popular, these measures were:

- a toolkit that could include information on OH referral and assessment processes

- a provider database

- an online questionnaire to help employers identify what type of services they could benefit from

- a comparison website

- information on the value of OH services

- basic online information on the process of procuring OH services

Government heard smaller employers would find basic online information about the process of procuring OH services more helpful than large employers, while micro employers and OH providers prioritised an online questionnaire that would help employers identify the types of services they could benefit from.

Improving quality

The consultation asked what indicators of quality and compliance arrangements would help employers to choose providers and improve the standard of services.

A range of quality indicators were supported by respondents. There was particular support from employers and OH providers for developing indicators with a closer or direct link to outcomes. Suggestions for outcome indicators included sickness absence, staff retention, satisfaction levels, return to work rates, and work modification implementation among others.

Several responses noted the need to ensure outcomes are measured in a robust and consistent way, and suggested that caution should be taken when using absence data as a metric on its own because changes in sickness absence rates may be influenced by a number of factors. A clear theme also emerged that outcome-linked indicators should start with better collation of data.

The majority of SEQOHS (Safe Effective Quality Occupational Health Service) members considered a SEQOHS accreditation as the best overall indicator of quality in the OH market and some respondents highlighted a potential opportunity to link into a review of SEQOHS.[footnote 62]

What government intends to do next

Building on the feedback from respondents, and linked to the national advice and information service (outlined in Chapter 1), Government is undertaking further design work with SME employers and self-employed people on how best to improve the process of choosing quality and cost-effective OH that meets their needs.

Government is interested in the potential for outcome-linked metrics to support continual provider improvement and employer choice. Given the considerations highlighted above, developing outcome-linked metrics is a longer-term challenge, but there may be short-term opportunities to make progress, and government is working with stakeholders and providers to explore these issues further.

Government has undertaken feasibility work with the NHS Getting It Right First Time programme (GIRFT) which is delivered in partnership with the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital and NHS England and NHS Improvement. GIRFT has experience using data and outcomes metrics to support sharing of best practice in the NHS. As a first step, government is working with GIRFT to pilot a best-practice methodology for collection of outcome metrics and to consider solutions to implement, build on and scale this methodology, as well as explore how employers might use data and outcomes to understand the value of occupational health.

Government is working with the Faculty of Occupational Medicine (FOM) as part of the FOM’s ongoing review of the SEQOHS standards and accreditation of services. Government has expressed its interest in the review exploring opportunities for SEQOHS to introduce stronger links with outcomes, and to increase engagement with employers and smaller providers.

Innovation in Occupational Health (OH)