Information pack for the consultation relating to a bilateral Free Trade Agreement between the United Kingdom and Australia (web/online version)

Updated 17 June 2020

Introduction

The Department for International Trade (DIT) is an international economic department responsible for securing UK and global prosperity by promoting and financing international trade and investment, and championing free trade. It is working to establish deeper trade and investment relationships with countries beyond the European Union.

As set out in the government’s White Paper ‘The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union’, the UK’s proposal for its future economic partnership with the EU would enable the UK to pursue an ambitious bilateral trade agenda. Negotiating and implementing free trade agreements (FTAs) with countries beyond the European Union is a key part of this.

Free trade agreements enable trade and investment, secure access for UK exporters to the markets of today and the future, give consumers access to a greater range of products at lower prices, and make the UK more innovative, competitive and prosperous.

Trade agreements aim to reduce trade barriers between countries. Barriers can be taxes charged on goods as they cross borders (tariffs), or different rules and regulations that can add to trade costs (non-tariff measures). Trade and investment barriers make it more difficult and costly to trade or invest overseas. Reducing these barriers can help the flow of goods, services and money for investment between countries, and help businesses to access markets they previously weren’t able to. Consumers can benefit from access to a greater variety of products at lower prices.

Trade agreements also have wider benefits. These can include:

- boosting economic growth in the UK by encouraging more competition, investment and innovation

- contributing to global prosperity, by boosting economic growth in countries that the UK does business with through international supply chains

- increased global prosperity supporting social cohesion within and between countries, and in turn political stability, which is one of the building blocks of our collective security

- benefits for developing countries – trade can be a vital tool in boosting developing countries’ economic growth and reducing poverty, while also providing UK consumers and businesses with goods at competitive prices

- an instrument of foreign policy – some countries use trade policy (including trade agreements) to advance standards and values

DIT is committed to using high-quality evidence to inform its trade policy. It is conducting a consultation to seek views from stakeholders on the economic, social and environmental impacts of an FTA with Australia.

The aims of this pack are to:

- provide stakeholders with background evidence to support the consultation

- clarify some of the terminology relating to FTAs

- provide information to respondents wishing to submit evidence setting out their views on the priority areas and expected impacts of an FTA with Australia

The pack provides a brief overview of the economic impacts of FTAs and the primary mechanisms through which they can affect businesses, consumers and workers.

Definition of a free trade agreement

A free trade agreement (FTA) is an international agreement which removes or reduces tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade and investment between partner countries.

Trade and investment barriers can make it more difficult and costly to trade or invest overseas. By removing or reducing them, FTAs can make it easier for businesses to export, import and invest. They can also benefit consumers by providing a more diverse and affordable range of imported products.

FTAs may be multilateral, plurilateral, regional or bilateral:

- multilateral agreements are agreed by all members of the World Trade Organization (WTO)

- plurilateral or regional agreements are agreed by subsets of WTO members

- bilateral agreements primarily relate to the liberalisation and regulation of trade and investment between the 2 signatories to the agreement

FTAs differ from customs unions. Parties to an FTA maintain independence to set their own tariffs on imports from nonparties. By contrast, all signatories of a customs union commit to apply the same external tariff to non-signatories.

FTAs do not prevent governments from regulating in the public interest – for example, to protect consumers, the environment, animal welfare and health and safety. Equally, trade agreements do not require governments to privatise any service or prevent governments from expanding the range of services they supply to the public. For example, the UK government has been clear about its commitment to protecting public services, particularly including the NHS. No future free trade agreement would affect the fact that it would remain up to the UK and devolved governments to decide how to run our publicly funded health services.

Scope of a free trade agreement

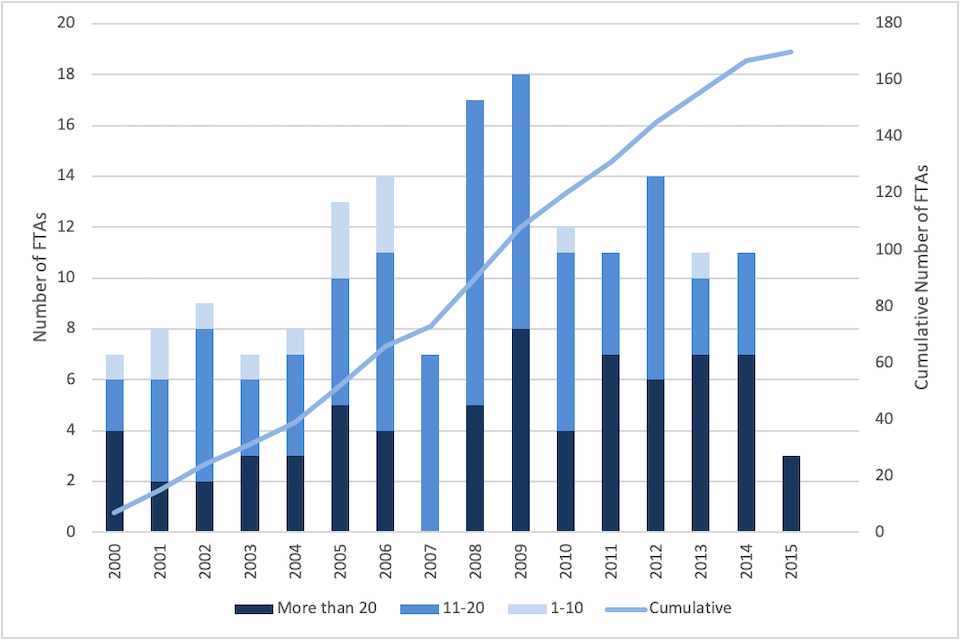

The number of free trade agreements (FTAs) around the world has grown substantially in recent decades (chart 1).

FTAs can vary in their scope and level of ambition. Less complex agreements focus more on trade in goods and the elimination of tariffs. Over time the scope and depth of FTAs has generally grown, including provisions addressing trade in services and investment. FTAs increasingly address domestic policies inhibiting trade and investment, known as “behind the border” barriers.

Chart 1: Number of bilateral trade agreements, by the number of provisions covered (2000-2015)

Source: DIT Analysis of the World Bank’s Content of Deep Trade Agreements Database. Coloured bars refer to the number of provisions in the FTA. The maximum number of provisions is 52.

Types of provisions included in Free Trade Agreements

The provisions included in free trade agreements (FTAs) vary across agreements. The World Bank has created a database that summarises the content of all FTAs that were in force and notified to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) as of 2015.[footnote 1] It covers 279 FTAs. For each agreement, the commitments are classified in 1 of 52 categories (outlined below) and distinguished according to whether or not they are legally enforceable.

Some areas of policy cooperation are more commonly included in FTAs than others. The World Bank classifies 18 of the 52 areas of policy cooperation as ‘core’ provisions. These are provisions which the World Bank identify as most meaningful from an economic point of view and have appeared most frequently in FTAs. ‘Non-core’ provisions – which sometimes go beyond areas directly associated with trade and investment – have appeared less frequently in FTAs. As with all provisions, their inclusion typically depends upon the specific objectives of an agreement and the preferences of the partners involved.

Areas of policy cooperation in past free trade agreements and economic partnership agreements

‘Core’ provisions (as defined by World Bank):

- tariffs on industrial goods

- tariffs on agricultural goods

- customs administration

- general Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

- export taxes

- sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS)

- state trading enterprises

- technical barriers to trade (TBT)

- trade related aspects of intellectual property rights (TRIPS)

- countervailing measures

- anti-dumping

- state aid/subsidies

- public procurement

- trade related investment measures (TRIMS)

- intellectual property rights (IPR)

- competition policy

- investment

- movement of capita

‘Non-core’ provisions:

- anti-corruption

- environmental laws

- labour market regulation

- consumer protection

- data protection

- agriculture

- political dialogue

- SMEs

- social matters

- visa and asylum

- approximation of legislation

- audiovisual

- civil protection

- innovation policies

- cultural cooperation

- economic policy dialogue

- public administration

- Statistics

- education and training

- energy

- financial assistance

- health

- human rights

- illegal immigration

- regional cooperation

- taxation

- illicit drugs

- industrial cooperation

- information society

- mining

- money laundering

- nuclear safety

- research and technology

- terrorism

Source: World Bank “Content of Deep Trade Agreements Database”[footnote 2]

A further description of these provisions is provided at the end of this document.

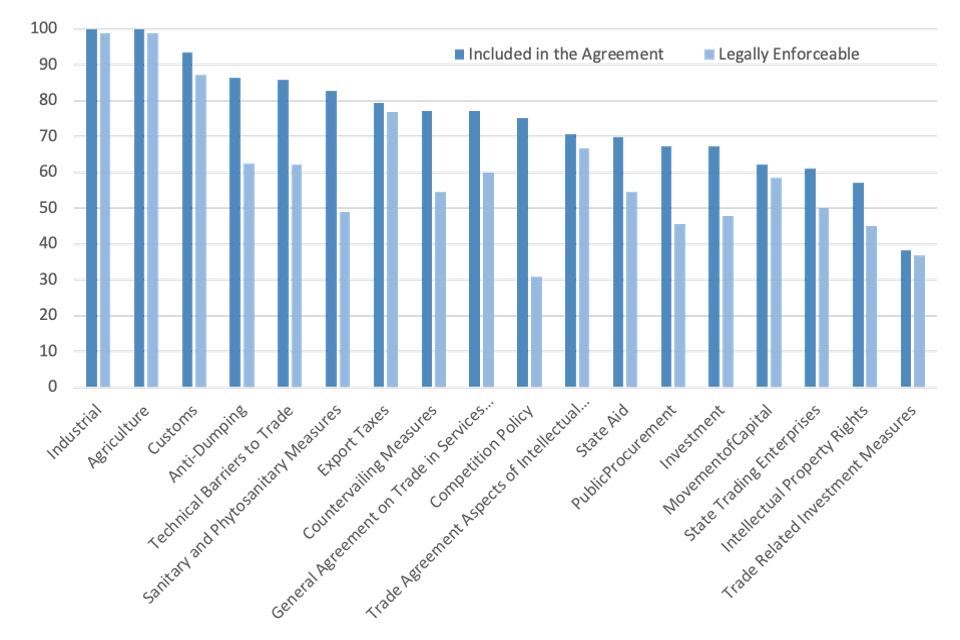

Chart 2 shows the proportion of FTAs which include each of the ‘core’ provisions.

Chart 2 – Percentage of bilateral FTAs that included specific ‘core provisions’ (agreements that entered into force between 2000 – 2015)

Source: DIT analysis of the World Bank’s “Content of Deep Agreements Database”. Analysis covered 198 agreements since 2000

Economic objectives of free trade agreements

Free trade agreements (FTAs) are expected to enhance economic growth and prosperity by:

- increasing import and export flows

- increasing investment flows (both outward and inward)

- enhancing productivity through a more efficient allocation of resources and greater openness to international competition

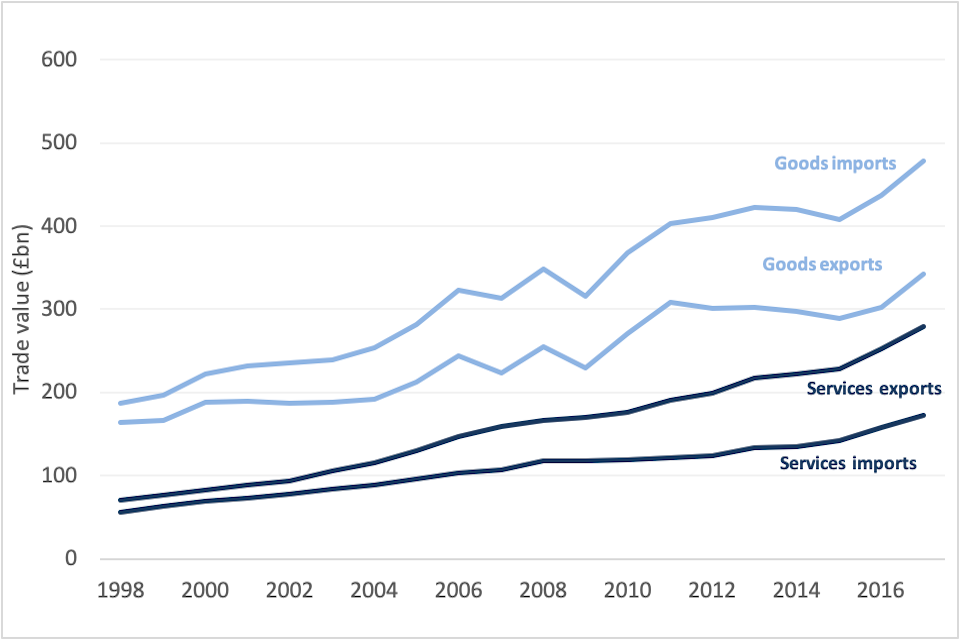

Free trade agreements and bilateral trade in goods and services. The UK is a highly open economy with trade (imports and exports together) equal in value to 62% of GDP.[footnote 3]

Chart 3 – UK trade in goods and services with the world (1998-2017)

Source: ONS UK Trade (March 2018), current prices.

Free trade agreements and trade in goods

Trade in goods represented 64% of all UK trade and 55% of UK exports in 2017.[footnote 4]

International trade in goods is subject to a wide range of tariff and non-tariff measures. These can significantly increase the costs and difficulties associated with international trade. Higher costs reduce the profitability of international trade, raise prices and reduce consumer choice globally.

Tariffs can be implemented in a range of ways, including ad valorem tariffs, non-ad valorem tariffs, tariff rate quotas and countervailing measures.[footnote 5] These can be levied with the objective of protecting domestic producers, raising revenues, or both.

Non-tariff measures (NTMs) are policy measures that may have an effect on trade by changing what can be traded, and at what price. For example, goods may need to comply with technical regulations. There can also be a need to meet requirements intended to protect humans, animals, and plants from diseases, pests, or contaminants. NTMs may occur at the border or ‘behind the border’. Behind the border refers to any NTMs that are applied inside an individual country but do not get checked at the border and therefore do not stop a product entering - for example labelling requirements.

NTMs can serve legitimate public policy objectives, and they do not all reduce trade. For example, the enforcement of high product standards may increase consumer demand for some goods. However, in other cases, non-tariff measures can act as barriers, raising trade costs and reducing trade.

FTAs can liberalise trade in goods by:

Addressing border barriers

Lowering costs:

Reducing tariffs between countries can increase opportunities for businesses that export and import, and improve choice for consumers. Tariff liberalisation may be immediate or phased over several years.

Providing greater certainty:

Countries sometimes apply lower tariffs than those they have committed to in their WTO schedules. FTAs can remove or reduce the gap between the maximum tariffs countries have committed to and the tariffs they apply in practice. This means that exporters and importers do not face the risk of tariffs suddenly being raised.

Providing greater ease:

FTAs can streamline customs procedures within partner countries to facilitate the entry of goods, reduce administrative costs and reduce delays. These measures reduce the costs of trade and allow production to take place across borders.

Addressing ‘behind-the-border’ barriers to goods trade

Removing or reducing non-tariff barriers to trade, and improving policy cooperation on non-tariff measures, can reduce the cost of trading products internationally. This can both increase the number of exporters and also increase the value of trade undertaken by existing exporters and importers.

Evidence suggests that FTAs can lead to large, sustained increases in trade in goods between partner countries. A review of many studies of the impacts of FTAs found that that they can boost total bilateral trade between partners by around 32%, although estimates from the literature vary widely.[footnote 6] A recent study by HM Treasury, based on different data sources and methodology, estimated that FTA membership is associated with a 17% increase in total trade, on average.[footnote 7] These studies indicate that deeper agreements tend to generate larger increases in trade. Evidence also suggests that trade flows continue to increase for up to 10 years after an agreement enters into force, meaning that the impacts of FTAs take time to be fully felt.[footnote 8]

Not all of the increases in bilateral trade between partners of an FTA represent additional trade at a global level. Some of the increases will have been diverted from trade with other countries that are not in the agreement.

From an economic perspective, free trade agreements provisions can reduce the fixed and variable costs associated with trading internationally, leading to an increase in both the number of exporting businesses and the value of exports from existing exporters.

Preferential tariffs and rules of origin (RoO)

Free trade agreements (FTAs) liberalise tariffs on a preferential basis between parties. Unlike in a customs union, members of an FTA can decide the tariffs which they apply to imports from any other country, and the FTA provides an opportunity for members to agree to offer each other preferential rates of tariffs below these generally applied levels. In order to ensure that only members of an FTA can benefit from these preferential tariff arrangements, the parties to the FTA need to agree a set of rules of origin to determine which goods imported from a partner country can qualify for preferential tariff treatment under the agreement. Rules of origin are necessary to prevent goods from other countries taking advantage of preferential tariff rates. However, implementing, administering and complying with rules of origin can generate costs.

There are 2 broad categories to determine whether goods have been substantially produced or transformed within the FTA countries and hence qualify as originating under an FTA:

- Wholly originating: the good must have been entirely created or produced in the partner country.

- Sufficient working or processing - this can take either one, or a combination of 1 or 2 or more of the following 3 forms:

a. Regional value content requirement: the final cost of a good must contain a certain percentage of value originating in a partner country;

b. Change in tariff classification: the production process must be sufficient to alter the HS Code classification of imported materials used in the production of the good, either by changing the HS2, HS4 or HS6 code;

c. Specific process rule: a good must undergo a set production process, for example a defined chemical reaction as set out in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The FTA sets out which of these rules each product must meet.

Free trade agreements and trade in services

Services are increasingly important for the UK economy, accounting for 79% of UK GDP in 2016.[footnote 9] Service sectors are also very important for UK trade. The UK consistently exports more services than it imports and ran a surplus in services trade of £112 billion in 2017.[footnote 10] In gross terms, services exports accounted for around 45% of total UK exports in 2017. However, when measured on a value-added basis, around two-thirds of the value of UK exports originate from services sectors.[footnote 11] This means that services provide an important source of inputs which are used to make UK exports.

As defined under the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), trade in services is categorised in 4 ways (modes):

- a company in one country can sell services across a border to consumers in another (mode 1)

- a consumer can buy services while abroad (mode 2)

- a company can establish a commercial presence abroad to provide services (mode 3)

- services suppliers can travel abroad to provide a service (mode 4).

Services trade is not subject to tariffs. However, each mode of service supply can be subject to a range of ‘behind-the-border’ measures. These may restrict the access of foreign service suppliers to the market or discriminate against foreign suppliers in favour of domestic suppliers.

As with non-tariff measures affecting trade in goods, regulatory barriers affecting services can achieve legitimate public policy objectives. However, in some cases, they have an unwanted effect of impeding trade in services and it is desirable to remove them.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) produces a Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, which measures the restrictions faced by foreign service suppliers in various sectors in over 40 countries.[footnote 12] The policies include:

- restrictions on foreign companies entering the market

- restrictions to the movement of people

- barriers to competition

- lack of regulatory transparency

- other discriminatory measures

It has become increasingly common to include services provisions within bilateral FTAs. According to the Design of Trade Agreements (DESTA) database, the number of bilateral agreements in force which included meaningful provisions relating to services trade rose from just 12 in 2000 to around 88 agreements by 2016.[footnote 13]

Members of the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) provide lists of commitments relating to maintaining the openness of their services sectors. In general, FTAs can provide opportunities to agree ‘GATS-plus’ provisions, such as:

- guaranteeing existing levels of market access;

- negotiating new market access in sectors of particular interest

- promising that the current FTA partner will be offered at least as good access as any future FTA partner (an extension of the ‘most favoured nation’ principle)

- improving transparency of domestic regulation such as standards, licensing and recognition of qualifications

Economic evidence suggests that deep trade agreements increase services trade if they include provisions on specific sectors and tackle pervasive behind-the-border barriers, such as regulatory alignment and national treatment rights.[footnote 14] Services and goods trade are interlinked, so that an open services sector is an important contributor to maintaining internationally competitive goods sectors.

From an economic perspective, FTAs liberalise trade in services via 3 channels:

1) Lowering barriers and levelling the playing field.

Liberalising services trade by lowering barriers allows for greater market access for foreign services suppliers.

2) Providing greater certainty.

‘Locking-in’ currently applied levels of market access ensures greater certainty for businesses and encourages new exporters to incur the fixed, sunk costs required to export their services.

3) Reducing costs.

Regulatory alignment and transparency can reduce the ‘compliance costs’ associated with meeting regulatory requirements of a trading partner’s regime to enable trade in services.

Free trade agreements and investment

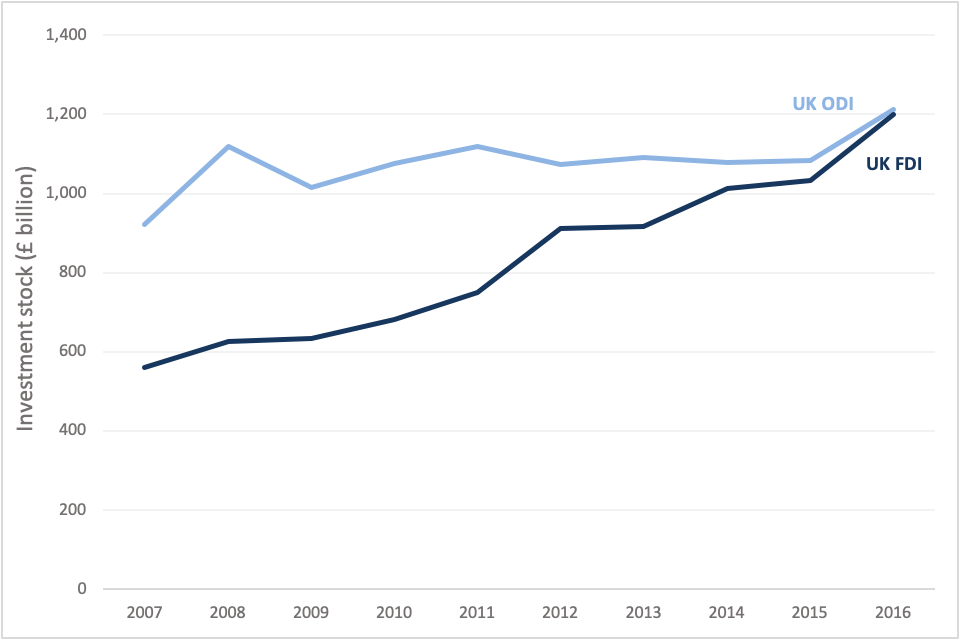

The UK is both a major destination and source of overseas direct investment. The value of the total stock of (inward) foreign direct investment (FDI) in the UK has been rising noticeably over recent years, from under £600 billion in 2007 to around £1.2 trillion in 2016. The value of the UK’s stock of outward direct investment (ODI) has been more stable over the last decade, and was also around £1.2 trillion in 2016.

Chart 4: Stock of Foreign Direct Investment to and from the UK (2007 – 2016)

Source: ONS ‘Foreign Direct Investment involving UK companies’, inward and outward tables

Investment between countries generates many economic benefits. It leads to a more competitive business environment, which in turn creates jobs, increases innovation and generates economic spill-overs to the rest of the economy.[footnote 15] There is also evidence of links between trade and investment.

Despite the benefits, global investment can be unnecessarily restricted by host government measures. Modern free trade agreements (FTAs) therefore increasingly include provisions relating to investment, including investment by establishing a commercial presence abroad. FTAs can seek to create a level playing field between domestic and foreign investors by prohibiting discrimination, market access barriers, and measures that could unduly distort investment flows. FTAs can also seek to increase certainty for investors by providing them with protections against arbitrary or manifestly unfair treatment. Addressing risk and uncertainty is particularly important for companies that may incur significant ‘sunk’ costs[footnote 16] when they invest. The right of governments to regulate in the public interest is recognised in investment chapters in FTAs.

There is evidence that FTAs can increase certain forms of investment.[footnote 17] This depends on the specific provisions within the agreement and the economies involved.[footnote 18]

Free trade agreements and productivity

‘Productivity’ is defined as the amount of output that an individual, firm, sector or economy can produce from a given level of inputs. Productivity growth is the single largest determinant of living standards and one of the principal determinants of long-run economic growth.

Theory suggests that openness to trade and investment may be an important driver of productivity growth. Trade liberalisation can result in a more efficient allocation of resources in the economy. It can shift the pattern of production in each country towards products and services in which the country has a comparative advantage. In doing so the price of goods and services across the economy can fall, benefiting consumers.

Greater opportunities to sell overseas should reward the most productive firms, allowing them to expand and attract investment, while competition encourages less productive firms to innovate and adapt. Competition can also provide companies with the incentive to invest in the skills of their workers, adopt better management practice and innovate in their use of capital, raising the productivity of firms and the workforce.

Empirical evidence seems to support this. The OECD estimates that a 10% increase in openness to trade is associated with a 4 per cent increase in income per head.[footnote 19]

Impacts: How different groups might be affected by a free trade agreement

Free trade agreements (FTAs) are expected to boost overall trade, investment and productivity. They can have different impacts on groups within society, such as businesses, consumers or workers.

Potential impacts of an FTA for businesses

FTAs can help businesses by expanding the size of the market into which they export. As well as increasing turnover, this can allow businesses to benefit from economies of scale, lowering their operating costs and raising profitability. This can help them attract investment and expand further.

By reducing barriers on imports, FTAs can reduce costs and expand the choice of imported inputs for businesses. This can help to raise the competitiveness of businesses.

Where they include investment provisions, FTAs can help to foster a favourable investment environment and provide a level playing field. This can help businesses to invest overseas more easily and attract investment from partners abroad.

Where FTAs reduce the fixed costs of exporting, they are likely to provide particular benefits for small and medium-sized enterprises. This can raise the number of smaller firms which find it profitable to export, helping to spur innovation and increase productivity.

The evidence shows that increased competition from trade promotes business innovation and growth. Some sectors may expand, creating more jobs and prosperity but some sectors or companies, which fail to adjust to such competition, can be adversely affected.

Administrative benefits and costs for businesses

According to the World Bank database on the content of FTAs, over 90% of the 279 agreements in the database include customs provisions.[footnote 20] Where these provisions address bottlenecks and streamline customs procedures, they can reduce the administrative or procedural costs faced by businesses when exporting and importing.

As with any economic policy, it can take time and effort for businesses to familiarise themselves with the changes. Businesses will incur some costs as they learn how to take advantage of the new commercial opportunities. FTAs can also generate additional administrative or compliance costs associated with meeting the requirements of rules of origin. Agreements can be designed in a simple and transparent manner to minimise the familiarisation costs and administrative burden caused by rules of origin.

Potential impacts of an FTA for consumers

At the heart of trade liberalisation is the expected benefit for consumers. Free trade agreements (FTAs) can directly benefit consumers in 2 ways:

1) Increases in product quality, variety and consumer choice.

Lowering trade costs between countries raises the probability that businesses will find it profitable to trade. This increases the number of firms that trade, and the variety of products traded.

2) Welfare gains from lower prices for existing products.

Reducing barriers on consumer goods and the regulatory barriers affecting cross-border trade in services can generate lower prices for consumers.

In addition, FTAs often benefit consumers indirectly through an impact on domestically produced goods. They can stimulate competition, resulting in lower prices for consumers. Domestic firms also benefit from improved choice, quality and lower prices of their intermediate inputs, which may be passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices.

Consumers can also be affected by specific provisions within FTAs. Applying the World Bank’s classification, the most relevant provisions are likely to relate to competition policy, consumer protections, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, technical barriers to trade and e-commerce. Consumers may regard the impact of specific provisions to be positive or negative depending on their individual perspectives and priorities.

As set out in the White Paper ‘Preparing for our future UK trade policy’, the UK government is committed to maintaining high standards of consumer protection for its citizens.

Economic evidence suggests that FTAs signed by developed nations such as the EU and US have indeed reduced consumer prices for their consumers and have increased the average quality of imported products.[footnote 21]

Potential impacts of an FTA for workers

Just as free trade agreements (FTAs) present opportunities and challenges for businesses, they also generate opportunities and challenges for the workers of those businesses. They can also affect the dynamism of the labour market more widely.

Workers can benefit from FTAs through a variety of channels:

-

where FTAs boost productivity within firms and sectors, and across the economy more widely, this is likely to generate increases in the employment opportunities and real wages of workers

-

where FTAs lower consumer prices, this is likely to benefit workers in the form of higher real wages, meaning that they can purchase more even at the same wage

Economic evidence shows that, on average, trade has benefited workers through increasing employment levels over the longer-term [footnote 22] and FTAs have had a positive impact on average real wages.[footnote 23]

Trade liberalisation can affect the structure of the economy over time. Workers may move between jobs and sectors, as changes in the pattern of trade lead to some sectors expanding and some sectors declining. Evidence shows that the UK has one of the most dynamic and flexible labour markets in the world, which helps to facilitate adjustment and reduce transitional costs for workers.[footnote 24]

Modern, dynamic economies are continually reshaping in line with global developments which drive a continual process of worker and job transition in the labour market. It is possible that lower barriers and greater import competition resulting from an FTA could accelerate this ongoing process.

Potential wider social impacts of a free trade agreement

As described above, free trade agreements (FTAs) can affect employment prospects, wages and wider working conditions in specific sectors or for specific professions or skill levels.

The characteristics of workers can sometimes differ across sectors, professions and skill levels. It is therefore possible that these changes could affect various social groups differently and influence the distribution of income.

The regional location of workers in different sectors and professions may also vary. This means that different areas or regions within a country may be affected differently by an FTA.

The impacts on different groups and regions will depend upon the details of each agreement. The government will assess the potential impacts on different groups in more detailed studies before and after negotiations take place with partner countries.

Potential impacts of a free trade agreement on the environment

The economic changes resulting from FTAs have the potential to affect some aspects of the environment including, for example, greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, water quality and land use.

The indirect impacts on the environment may occur as enhanced trade induces the economy to grow (a ‘scale’ effect affecting pollution for example) and as economic activity shifts between sectors with different levels of emissions (a ‘composition’ effect). FTAs can also positively impact the environment as increased trade leads to the transfer of new, potentially more environmentally friendly, technologies and production methods (a ‘technique’ effect).

The impact of FTAs on the environment will depend upon the design of an agreement and the economies of the countries involved. As set out in the 2017 White Paper ‘Preparing for our future UK trade policy’, the UK government is committed to maintaining high standards of environmental protection in trade agreements. The government will assess the potential environmental impacts in more detailed studies before and after negotiations take place with partner countries.

Trade and investment relationship between the United Kingdom and Australia

A free trade agreement (FTA) between Australia and the UK represents an important opportunity to deepen the bilateral trade and investment relationship. This information note provides an overview of the existing bilateral trade and investment relationship between the 2 countries.

The UK and Australia have a long history of cooperation in international trade and investment forums. Both countries are leading voices on the liberalisation of trade in services and have been vocal champions of important agendas such as the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) and the e-commerce and domestic regulation work in the World Trade Organization (WTO).

On investment, the UK and Australia have made common commitments through Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) instruments. These commitments include the OECD Code of Liberalisation of Capital Movements - which provides a framework for countries to remove unnecessary barriers to the movement of capital. It also includes the Code of Liberalisation of Invisible Operations - which provides a framework for countries to remove services barriers. Australia and the UK work alongside other OECD members through the OECD Investment Committee to further their objectives on investment.

Facts and figures for bilateral trade and investment flows

Economies of the United Kingdom and Australia

The UK and Australian economies are similar in structure, although UK gross domestic product (GDP) is twice that of Australia. The services sector accounts for 79% of economic output in the UK and 73% in Australia. Both economies are highly engaged in global trade. Trade (imports plus exports) is equivalent to a higher proportion of UK GDP, at 59% compared to 41% for Australia.

Figure 1 – Headline economic indicators for Australia and the United Kingdom

| Economic indicator (2016 unless specified) | Australia | UK |

|---|---|---|

| GDP (Purchasing power parity (PPP[footnote 25]), 2011 prices) | $1.08 trillion | $2.58 trillion |

| GDP per capita (PPP, 2011 prices) | $44,494 | $39,309 |

| Trade (% GDP) | 41% | 59%[footnote 26] |

| Population | 24.2 million | 65.6 million |

| Agriculture, value added (% GDP) | 2.6% | 0.6% |

| Industry, value added (% GDP) | 24.3% | 20.2% |

| Services, value added (% GDP) | 73.1% | 79.2% |

Source: World Bank Development Indicators, sector value added data retrieved as of May 2018

Bilateral trade flows

The following statistics highlight the trade flows between the UK and Australia:[footnote 27]

- total trade in goods and services (exports plus imports) between the UK and Australia was £13.1 billion in 2016, a 0.8% decrease from 2015

- of all UK exports to Australia in 2016, 48% were goods and 52% in services. This compares to UK exports to the EU in which 61% were goods and 39% services

- of all UK imports from Australia in 2016, 46% were goods and 54% were services

Trade in goods

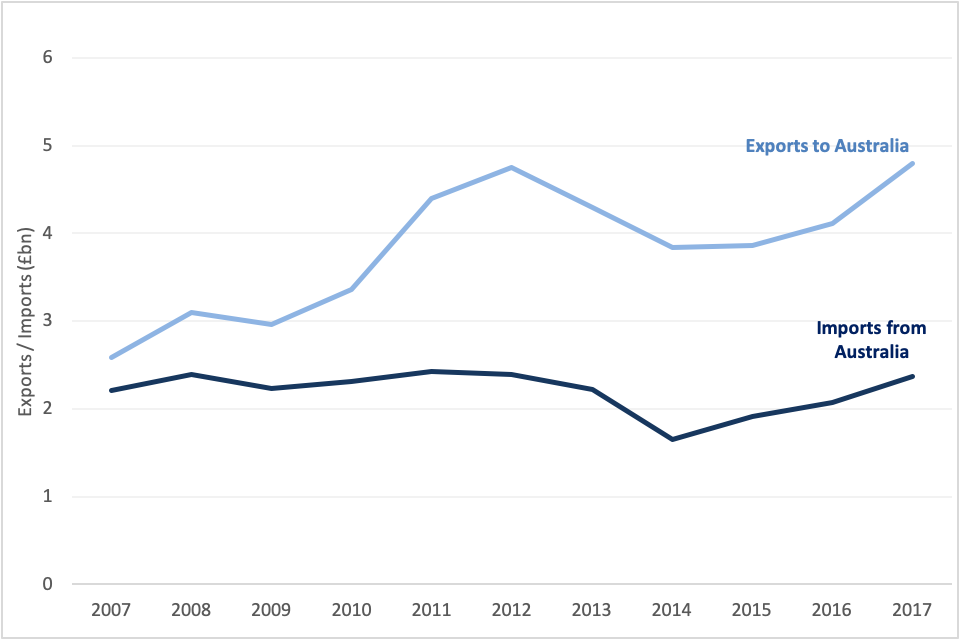

As shown in Figure 2, the UK exports a higher quantity of goods than it imports from Australia, leading to a trade surplus on goods. This trade surplus has been gradually increasing over the past 10 years as growth in the UK’s goods exports to Australia has exceeded growth in goods imports from Australia.

Figure 2 – UK goods exports and imports to and from Australia (2007-2017)

Source: Office for National Statistics, UK Trade (March 2018), values in current prices

Trade in goods by sector

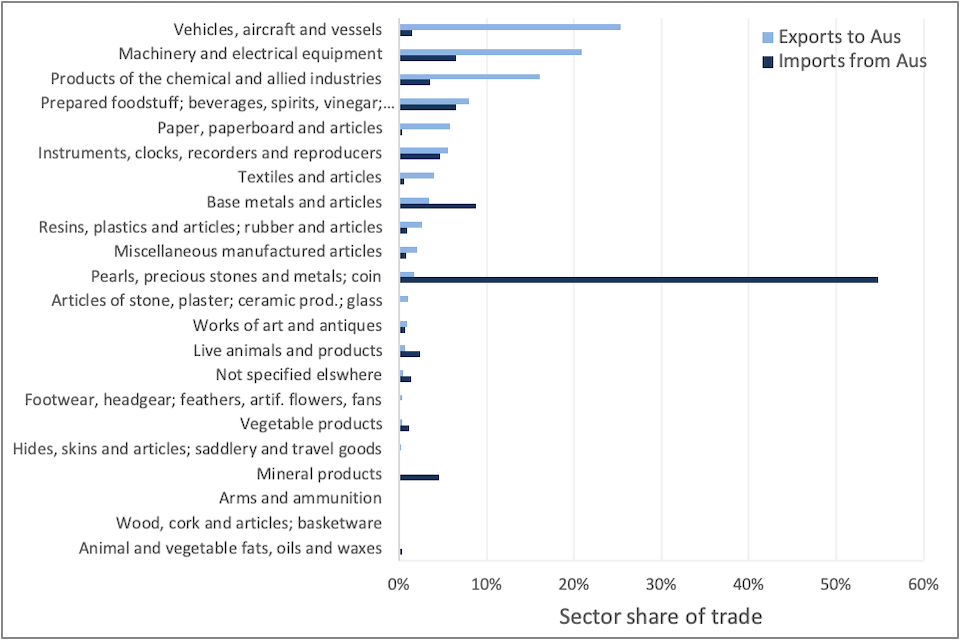

As shown in Figure 3, the pattern of goods the UK exports to Australia differs from the pattern of goods imported from Australia, showing complementarity in the trade relationship. The 3 goods sectors in which the UK exports the most to Australia are:

- vehicles and aircraft

- machinery and electrical equipment

- chemicals

The 3 goods sectors in which Australia exports the most to the UK are:

- pearls and precious metals

- base metals

- prepared foodstuffs

Figure 3 – Bilateral goods trade between the UK and Australia, broken down by sector (average 2015-2017)

Source: HMRC trade statistics by commodity code. Sectors classified according to Harmonised System Sections. Data uses an average from 2015 to 2017.

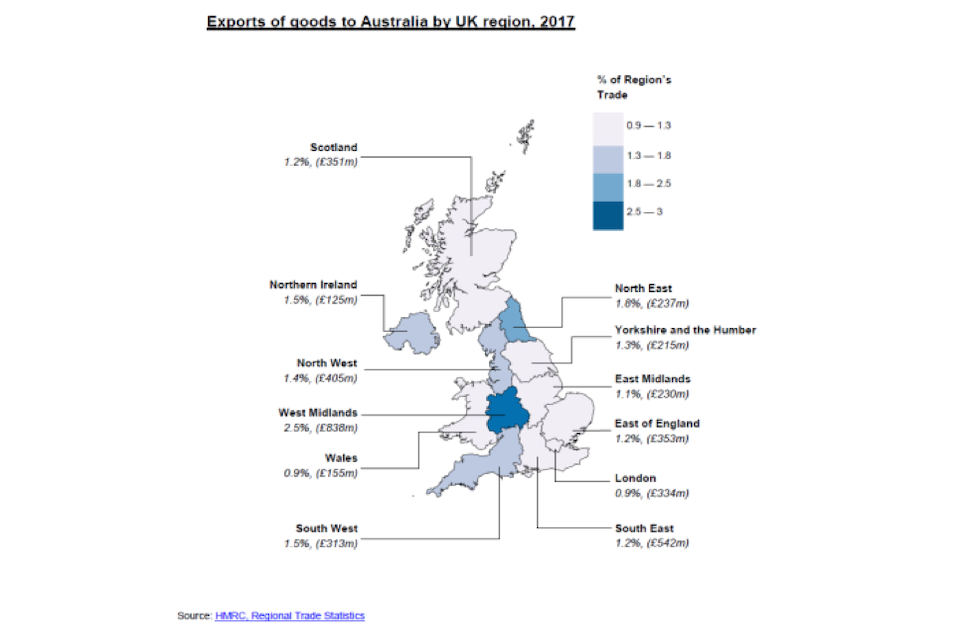

Trade in goods by region

The UK’s exports of goods to Australia are most highly concentrated in the West Midlands, where exports to Australia make up 2.5% of the region’s trade.

Figure 4 – Exports of goods to Australia by UK region, 2017

Source: HMRC regional trade statistics

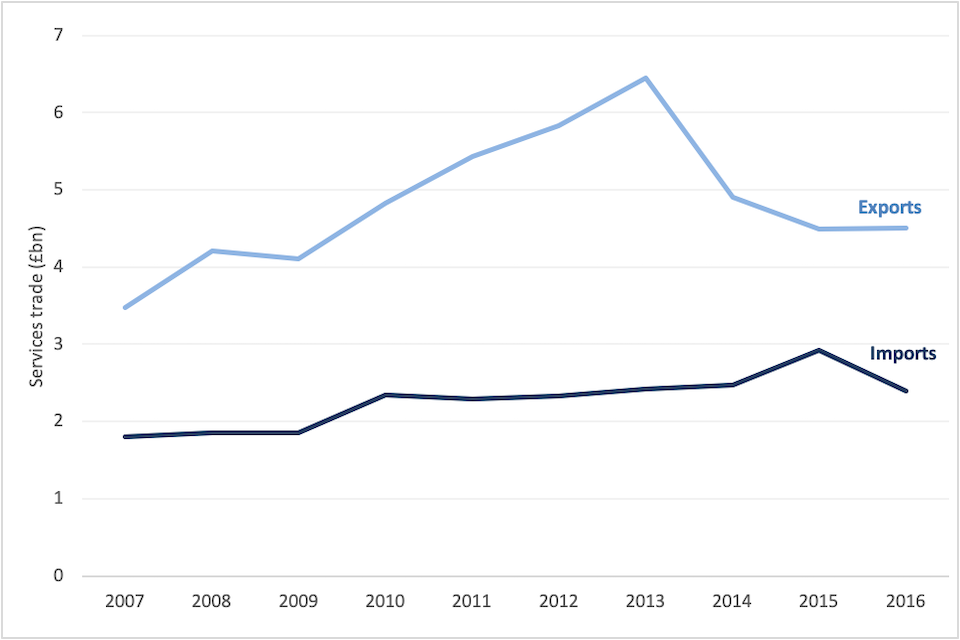

Trade in services

As shown in Figure 5, the UK exports a larger volume of services than it imports from Australia, leading to a trade surplus in services. This trade surplus has remained relatively stable over the past 10 years as growth in the UK’s exports to Australia has kept pace with growth in the UK’s imports from Australia.

Figure 5 – UK services exports to and imports from Australia (2007-2016)

Source: Office for National Statistics, Economic Accounts, March 2018

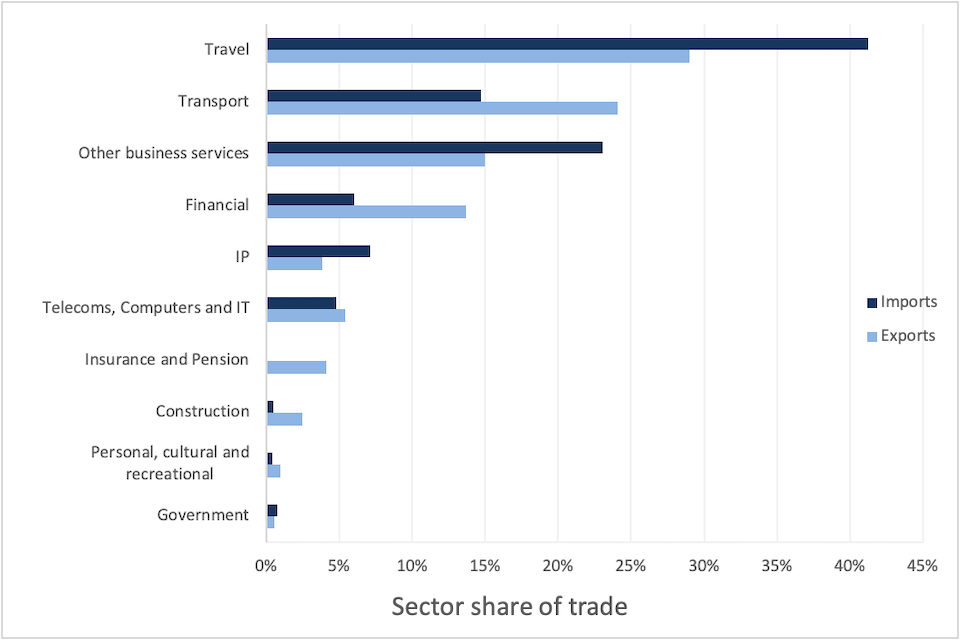

The UK’s main services exports to Australia are categorised by the Office of National Statistics as:

- travel

- transport

- other business services

- financial services

‘Other business services’ includes auditing, accounting and legal services. The UK has the largest services trade surplus with Australia in financial services and insurance and pension services.

Figure 6 – Bilateral services trade between the UK and Australia, broken down by sector (average 2014-16)

Source: Office for National Statistics: User Requested Data, 2017 – Trade in Services data.

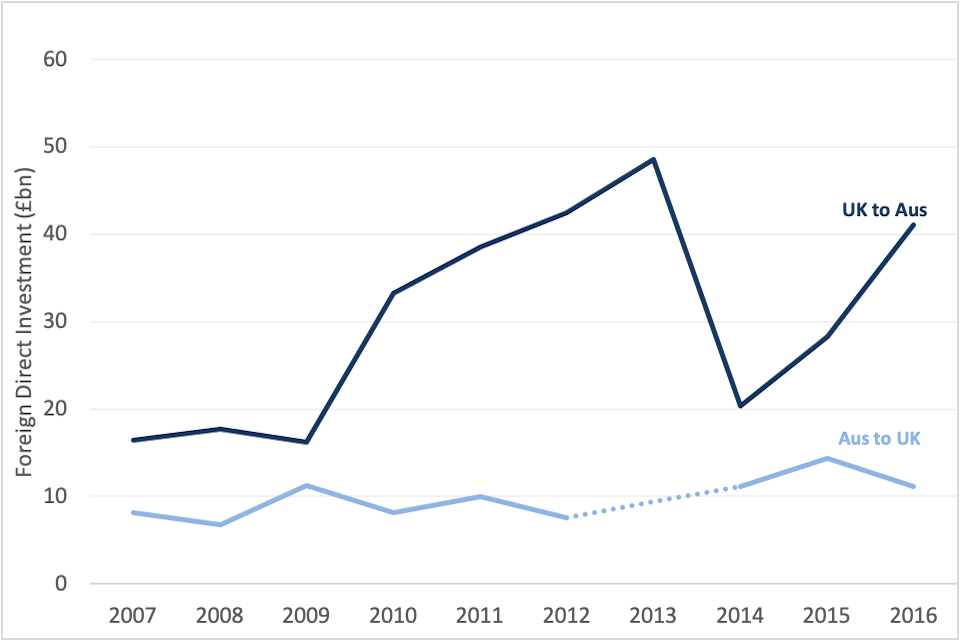

Investment stock

The total amount of UK Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) invested in Australia (outward investment stock) was £41 billion in 2016. This accounted for 3.4% of total UK outward FDI stock.[footnote 28]

The stock of Australian FDI invested in the UK (inward investment) was £11.1 billion in 2016. This accounted for approximately 0.9% of total UK inward FDI stock.[footnote 29] Over the last decade there has been an upward trend in UK FDI invested in Australia, whilst Australian FDI stock in the UK has remained relatively stable.

Figure 7 – Australian FDI in the UK and UK FDI into Australia (2007-2016)

Source: Office for National Statistics, Foreign Direct Investment Involving UK Companies, 2016. FDI data refers to stocks. Data for 2013 not available

Evidence relating to trade and investment barriers

A free trade agreement (FTA) can help remove trade barriers between countries, supporting increased trade and investment between those partners. The main barriers to trade are tariffs (which only apply to goods), non-tariff barriers (which affect both goods and services) and investment barriers.

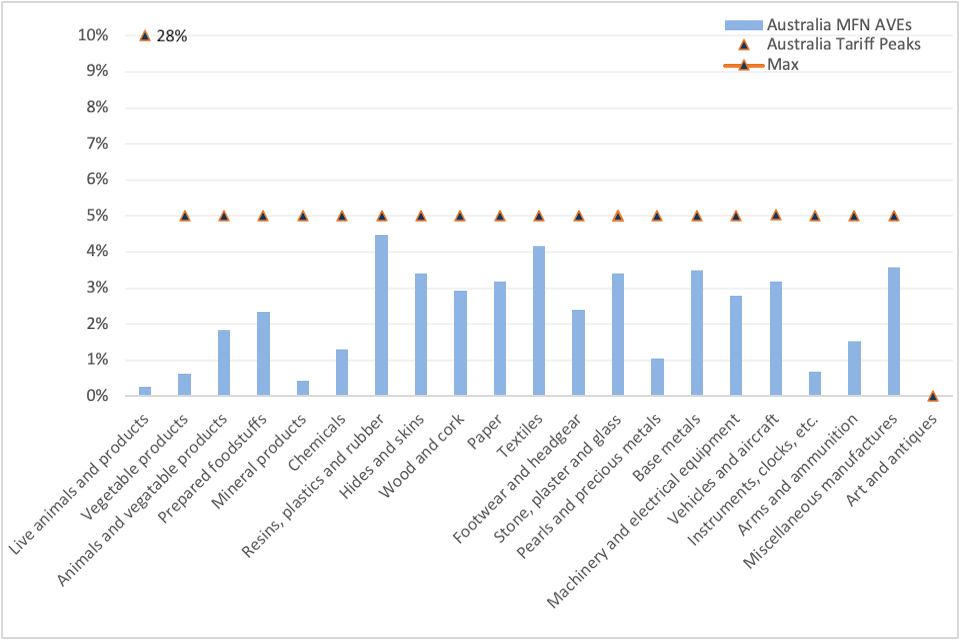

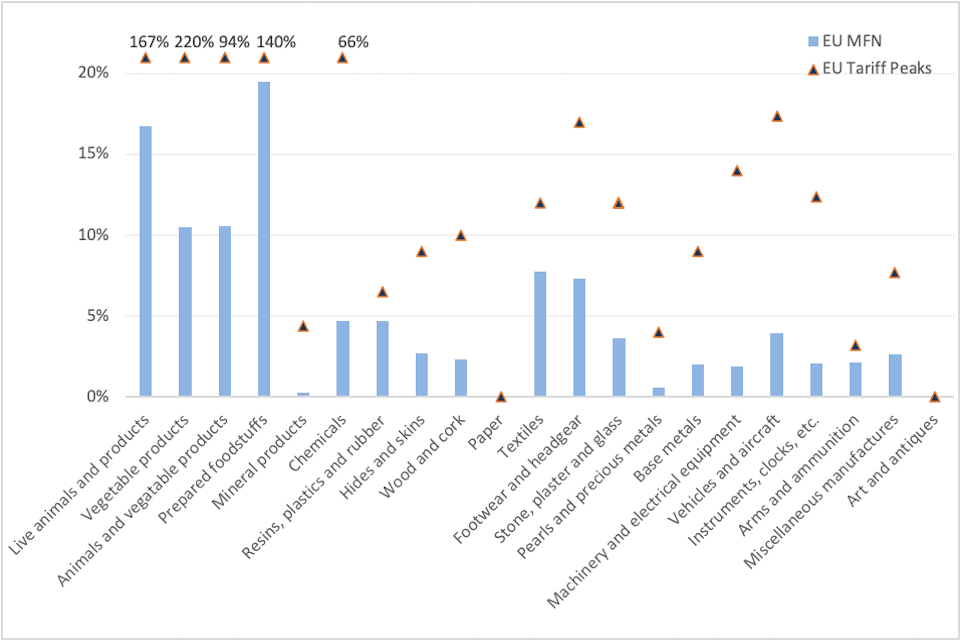

International evidence relating to barriers affecting trade in goods

Tariffs are customs duties on goods imported into a country. The simple average tariff on goods imported into the UK is 5.7% and for Australia it is 2.5%. On a trade-weighted basis - adjusting for the specific value of bilateral UK-Australia trade in different sectors - the average tariff on Australian imports into the UK is 3.2% and for UK goods imported into Australia it is 3.0%.

Figure 8 – Tariffs applied by Australia and the UK[footnote 30]

| Australia | UK | |

|---|---|---|

| Simple average tariff | 2.5% | 5.7% |

| Trade weighted average (based on UK-US bilateral trade) | 3.0% | 3.2% |

| % of goods with no duty (HS 6-digit goods categories) | 47.4% | 26.0% |

| % of goods with tariffs above 15% (HS 6-digit good categories) | 0.01% | 5.7% |

Source: World Bank Integrated Trade Solution, DIT calculations. Data for 2016.

Applied tariffs vary across different types of goods. Across the 21 goods categories,[footnote 31] the UK’s average tariffs[footnote 32] vary from 0% on paper goods to around 20% on prepared foods. Australia’s tariffs vary from 0.3% on animals and animal products to 5% on rubber and plastic goods. Peak UK tariffs - the highest level of tariff on specific goods within each product category - are 220% on vegetable products, compared to 28% on live animals and products in Australia.

Figure 9 – Australian Tariff Composition (% ad-valorem equivalent[footnote 33])

Source: World Bank Integrated Trade Solution, DIT calculations. Data for 2016.

Figure 10 - EU Tariff Composition (% ad-valorem equivalent)

Source: World Bank Integrated Trade Solution, DIT calculations. Data for 2016.

Non-tariff measures affecting trade in goods

A non-tariff measure is defined as being any policy measure other than customs tariffs that can potentially affect the quantity or price of international trade.

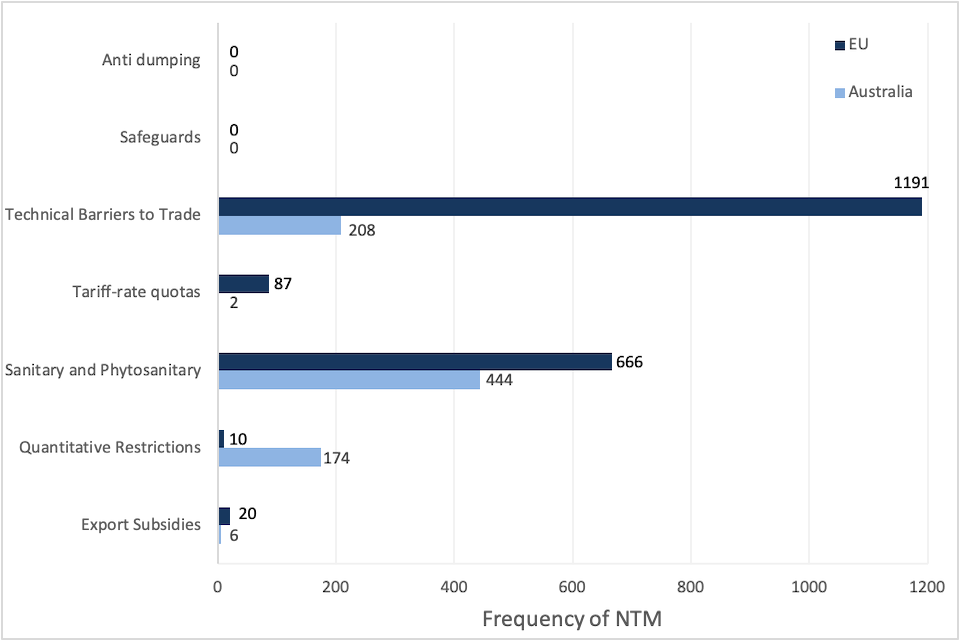

Data from the World Trade Organisation’s Integrated Trade Intelligence Portal (I-TIP) shows that the greatest number of non-tariff measures in Australia fall under the category of sanitary and phytosanitary measures. This is a category which covers any standards which a country applies to ensure food safety, animal health or plant health standards.

In comparison to the EU, Australia has a greater number of quantitative restrictions (limits on the quantity or value of goods that can be imported or exported during a specific period), but fewer sanitary and phytosanitary measures and technical barriers to trade (which include regulations, standards and procedures required to ensure that domestic legislative requirements are met).

Figure 11 – Non-tariff measures in Australia, by frequency

Source: WTO, Integrated Trade Intelligence Portal (I-TIP). NTMs either initiated or in force at 30/06/2018.

International evidence relating to barriers affecting trade in services

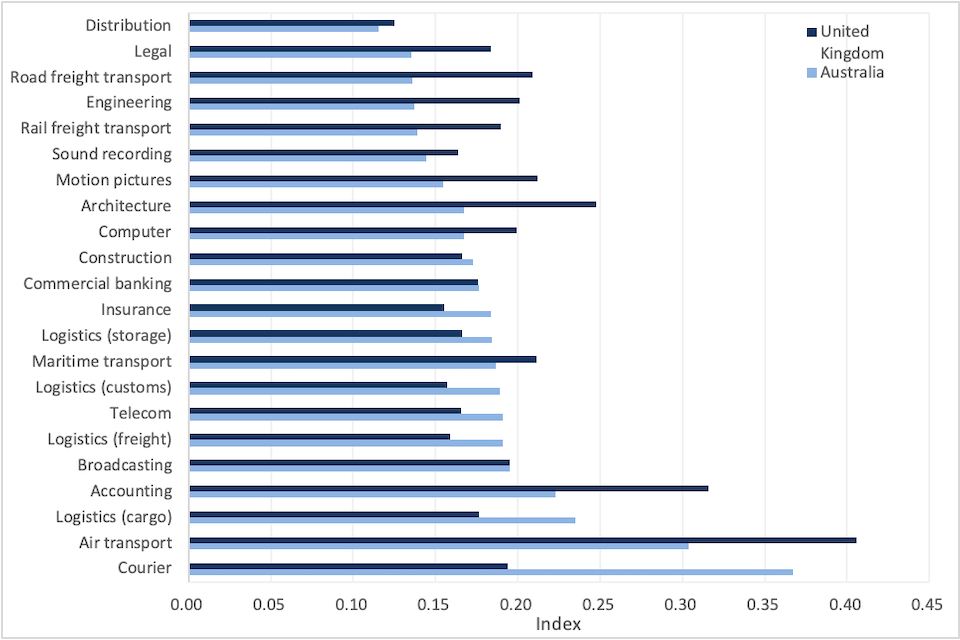

The OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) provides an assessment of trade in services barriers across 22 sectors. A higher STRI value indicates higher regulatory requirements that are needed for exporters to provide services in that country. The sectors with the highest STRI values in Australia are in courier services, air transport and logistics/cargo-handling services. For the UK, these are in air transport, accounting and architecture.

Figure 12 – Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) in the UK and Australia

Source: OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI). 2017 data.

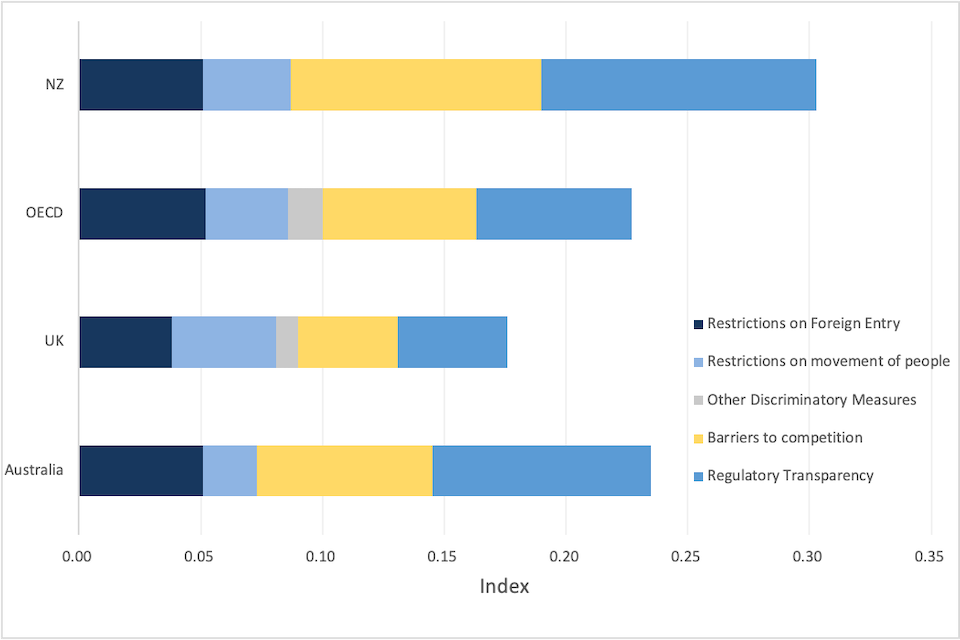

Australia has a lower level of services trade restrictiveness than the UK and New Zealand. All 3 countries have lower levels of services trade restrictiveness than the OECD average.

Figure 13 – Australia Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, by type of restriction

Source: OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), 2017 data.

Restrictions on foreign direct investment

Investment provisions within a trade agreement can help create a level playing field for domestic and foreign investors by limiting discriminatory rules and increasing market access. It also seeks to increase certainty, and in turn lower costs associated with foreign investment projects, thus reducing risks for business.

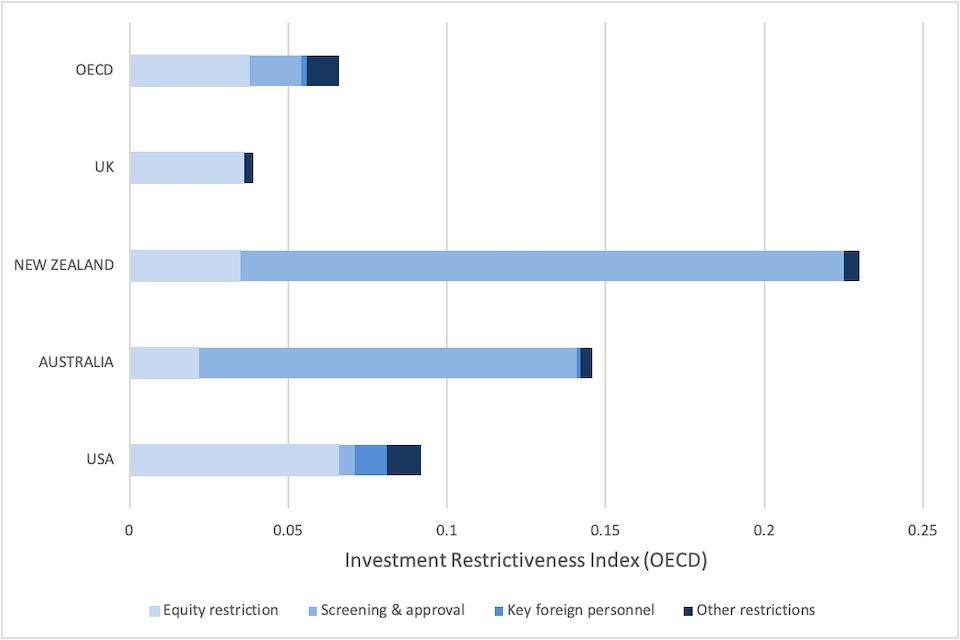

The OECD’s FDI Restrictiveness Index assesses the restrictiveness of a country’s foreign direct investment (FDI) rules by looking at 4 main types of barrier to foreign investment:

- foreign equity restrictions

- discriminatory screening or approval mechanisms

- restrictions on key foreign personnel

- operational restrictions

The OECD FDI Restrictiveness Index shows Australia to be relatively restrictive to foreign investment. The majority of Australia’s barriers to FDI fall under the category of ‘screening and approval’ restrictions. This category includes any obligatory procedures investors must undergo before obtaining approval for their planned investment.

Figure 14 – Australian investment restrictiveness, by type of restriction

Source: OECD Investment Restrictiveness Index. Data taken for year 2017

Conclusion from analysis

The international evidence shows that free trade agreements (FTAs) have the potential to deliver substantial economic benefits to an economy, including increased trade, investment and productivity. Transparent, well designed FTAs have the potential to benefit businesses, consumers and workers alike.

The evidence suggests that Australia is an important trade and investment partner and that deepening the trade and investment relationship through an FTA could generate benefits to the UK and Australian economies.

The international evidence also suggests that FTAs generate a range of opportunities and challenges. This consultation will inform an evidence based approach to decision-making and inform future assessments of the impacts of an FTA with Australia.

The UK government has committed to publishing scoping assessments before entering into negotiations with partner countries, and to publishing an impact assessment later in the process, at an appropriate time.

Description of provisions in the Content of Deep Trade Agreements Database

| WTO-plus areas | Description |

|---|---|

| FTA industrial | Tariff liberalization on industrial goods; elimination of non-tariff measures |

| FTA agriculture | Tariff liberalization on agriculture goods; elimination of non-tariff measures |

| Customs | Provision of information; publication on the Internet of new laws and regulations; training |

| Export taxes | Elimination of export taxes |

| SPS | Affirmation of rights and obligations under the WTO Agreement on SPS; harmonization of SPS measures |

| TBT | Affirmation of rights and obligations under WTO Agreement on TBT; provision of information; harmonization of regulations; mutual recognition agreements |

| STE | Establishment or maintenance of an independent competition authority; non-discrimination regarding production and marketing condition; provision of information; affirmation of article XVII GATT provision |

| AD | Retention of Antidumping rights and obligations under the WTO Agreement (article VI GATT) |

| CVM | Retention of Countervailing measures rights and obligations under the WTO Agreement (article VI GATT) |

| State aid | Assessment of anticompetitive behaviour; annual reporting on the value and distribution of state aid given; provision of information |

| Public procurement | Progressive liberalisation; national treatment and/or non-discrimination principle; publication of laws and regulations on the Internet; specification of public procurement regime |

| TRIMs | Provisions concerning requirements for local content and export performance of FDI GATS Liberalisation of trade in services |

| TRIPs | Harmonisation of standards; enforcement; national treatment, most-favoured nation treatment |

| Anti-corruption | Regulations concerning criminal offence measures in matters affecting international trade and investment |

| Competition policy | Maintenance of measures to proscribe anticompetitive business conduct; harmonisation of competition laws; establishment or maintenance of an independent competition authority |

| Environmental laws | Development of environmental standards; enforcement of national environmental laws; establishment of sanctions for violation of environmental laws; publications of laws and regulation |

| IPR | Accession to international treaties not referenced in the TRIPs Agreement |

| Investment | Information exchange; Development of legal frameworks; harmonisation and simplification of procedures; national treatment; establishment of mechanism for the settlement of disputes |

| Labour market regulation | Regulation of the national labour market; affirmation of International Labour Organization (ILO) commitments; enforcement |

| Movement of capital | Liberalisation of capital movement; prohibition of new restrictions |

| Consumer protection | Harmonisation of consumer protection laws; exchange of information and experts; training |

| Data protection | Exchange of information and experts; joint projects |

| Agriculture | Technical assistance to conduct modernisation projects; exchange of information |

| Approximation of legislation | Application of EC legislation in national legislation |

| Audio visual | Promotion of the industry; encouragement of co-production |

| Civil protection | Implementation of harmonised rules |

| Innovation policies | Participation in framework programmes; promotion of technology transfers |

| Cultural cooperation | Promotion of joint initiatives and local culture |

| Economic policy dialogue | Exchange of ideas and opinions; joint studies |

| Education and training | Measures to improve the general level of education |

| Energy | Exchange of information; technology transfer; joint studies |

| Financial assistance | Set of rules guiding the granting and administration of financial assistance |

| Health | Monitoring of diseases; development of health information systems; exchange of information |

| Human rights | Respect for human rights |

| Illegal immigration | Conclusion of re-admission agreements; prevention and control of illegal immigration |

| Illicit drugs | Treatment and rehabilitation of drug addicts; joint projects on prevention of consumption; reduction of drug supply; information exchange |

| Industrial cooperation | Assistance in conducting modernisation projects; facilitation and access to credit to finance |

| Information society | Exchange of information; dissemination of new technologies; training |

| Mining | Exchange of information and experience; development of joint initiatives |

| Money laundering | Harmonisation of standards; technical and administrative assistance |

| Nuclear safety | Development of laws and regulations; supervision of the transportation of radioactive materials |

| Political dialogue | Convergence of the parties’ positions on international issues |

| Public administration | Technical assistance; exchange of information; joint projects; training |

| Regional cooperation | Promotion of regional cooperation; technical assistance programmes |

| Research and Technology | Joint research projects; exchange of researchers; development of public-private partnership |

| SME | Technical assistance; facilitation of the access to finance |

| Social matters | Coordination of social security systems; non-discrimination regarding working conditions |

| Statistics | Harmonisation and/or development of statistical methods; training |

| Taxation | Assistance in conducting fiscal system reforms |

| Terrorism | Exchange of information and experience; joint research and studies |

| Visa and asylum | Exchange of information; drafting legislation; training |

References

Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2007). Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics, 71(1), 72-95.

Berger, A., Busse, M., Nunnenkamp, P., & Roy, M. (2012). Do trade and investment agreements lead to more FDI? Accounting for key provisions inside the black box. International Economics and Economic Policy, 10(2).

Breinlich, H., Dhingra, S., & Ottaviano, G. (2016). How Have EU’s Trade Agreements Impacted Consumers? London: Centre for Economic Performance.

Büthe, & Milner. (2014). Foreign Direct Investment and Institutional Diversity in Trade Agreements: Credibility, Commitment, and Economic Flows in the Developing World, 1971-2007. World Politics, 66(1), 88-122.

Caliendo, L., & Parro, F. (2015). Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA. The Review of Economic Studies, 82(1), 1-44.

Cernat, L., Gerard, D., Guinea, O., & Lorenzo, I. (2018). Consumer benefits from EU trade liberalisation: How much did we save since the Uruguay Round? Chief Economist Unit, DG TRADE.

Dür, A., Baccini, L., & Elsig, M. (2014). The design of international trade agreements: Introducing a new dataset. The Review of International Organizations, 9(3), 353-375.

Ebell, M. (2016). Assessing the impact of trade agreements on trade. National Institute Economic Review, 238(1), R31-R42.

Egger, P., Francois, J., Machin, M., & Nelson, D. (2015). Non-tariff barriers, integration and the transatlantic economy. Economic Policy, 30(83), 539-584.

Guillin, A. (2013). Trade in services and Regional Trade Agreements: do negotiations on services have to be specific? The World Economy, 26(11), 1393-1405.

Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2013). Gravity Equations: Workhorse, Toolkit, and Cookbook. CEPII.

HMG. (January 2014). Outward Investment: Selected Economic Issues. HMG.

HMT. (2016). HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives. HM government.

Hoffman, C., Osnago, A., & Ruta, M. (2017). Horizontal Depth A New Database on the Content of Preferential Trade Agreements. Policy Research Working Paper, 7891.

Horn, H., Mavroidis, P. C., & Sapir, A. (2010). Beyond the WTO? An anatomy of EU and US preferential trade agreements. The World Economy, 33(11), 1565-1588.

Kim, Lee, & Tay. (2017). Setting up Shop in Foreign Lands: Do Investment Commitments in PTAs Promote Production Networks? The Political Economy of international Organizations 10th Annual Conference. University of Bern, Switzerland.

Kohl, T., Brakman, S., & Garretsen, H. (2016). Do Trade Agreements Stimulate International Trade Differently? Evidence from 296 Trade Agreements. World Econ, 39, 97-131.

Lejarraga, & Bruhn. (2017). Mapping investment-related provisions in regional trade agreements from a global value chain perspective. https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/INV/WD(2017)17/en/pdf: OECD Investment Committee .

Lin, H., & Yeh, R.-S. (2006). The interdependence between FDI and R&D: an application of an endogenous switching model to Taiwan’s electronics industry. Applied Economics, 37(15), 1789-1799.

McLaren, J. (2017). Globalization and Labor Market Dynamics. Annual Review of Economics, 177-200.

OECD. Sources of Economic Growth in OECD Countries. (25th February 2003). Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Paris, France. p88

Osnago, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (2015). Deep Trade Agreements and Vertical FDI: The Devil is in the Details. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7464.

Szkorupová, Z. (2015). Relationship between Foreign direct investment and domestic investment in selected countries of central and Eastern Europe. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 1017-1022.

Trefler, D. (2006). The Long and Short of the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement. London, UK: Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Political Science, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Van der Marel, E., & Shepher, B. (2012). Services Trade, Regulation, and Regional Integration: Evidence from Sectoral Data. The World Economy, 26(11), 1393-1405.

Van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & Lichtenberg, F. (2001). Does Foreign Direct Investment Transfer Technology Across Borders? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(3), 490-497.

Velde, & Bezemer. (2006). Regional integration and foreign direct investment in developing countries. Transnational Corporations, 15(2).

Williamson, I. A., Pinkert, D. A., Johanson, D. S., Broadbent, M. M., Kieff, F. S., & Schmidtlein, R. K. (2016). Economic Impact of Trade Agreements Implemented Under Trade Authorities Procedures, 2016 Report. USITC.

Legal disclaimer

Whereas every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this document is accurate, the Department for International Trade does not accept liability for any errors, omissions or misleading statements, and no warranty is given or responsibility accepted as to the standing of any individual, firm, company or other organisation mentioned.

Copyright

© Crown Copyright 2018

You may re-use this publication (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Email [email protected] for further information on the licence.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information in the material that you wish to use, you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holder(s) concerned.

-

Hoffman et al. (2017) ↩

-

Hoffman et al. (2017) ↩

-

ONS UK Trade (March 2018), ONS GDP releases ↩

-

ONS UK Trade (March 2018), current prices ↩

-

Ad valorem tariffs are based upon a percentage of the value of a good, while non-ad valorem tariffs are based on the weight or the ingredients within a good. Tariff rate quotas allow a specific quantity of goods to enter at a reduced or tariff-free rate before higher duties are charged. Countervailing measures are duties levied on goods from countries which may have unfair state subsidies ↩

-

Head & Mayer (2013) ↩

-

HMT (2016) (PDF, 6,343KB) ↩

-

See for example: Egger et al. (2015); Baier & Bergstrand (2007) ↩

-

ONS UK gross domestic product (output approach) low-level aggregates ↩

-

ONS UK trade: goods and services publication tables ↩

-

OECD Trade in Value Added dataset ↩

-

The Design of Trade Agreements database (DESTA) assesses the content of over 600 trade agreements from 1948 to 2016. (Dür et al., 2014) ↩

-

See for example: Guillin (2013); Lamprecht and Miroudot (2018) ↩

-

See for example: technology transfers from investment in R&D-intensive countries (Van Pottelsberghe and Luchtenberg, 2001), positive impact on economic growth (Szkorupova, 2014), increase on employment, productivity and competitiveness (HMG, 2014), R&D (Lin and Yeh, 2005) ↩

-

A sunk cost is a cost that once a business pays can no longer be recovered by any means. ↩

-

See for example: Lejarraga and Bruhn, 2017, Velde and Bezemer, 2006, Büthe and Milner, 2014, Kim, Lee and Tay, 2017, Kohl, Brakman and Garretsen, 2016, and Berger et al., 2013. ↩

-

For example vertical foreign direct investment: Osnago et al., 2015 ↩

-

OECD. Sources of Economic Growth in OECD Countries (Feb 2003) ↩

-

Hoffman et al. (2017) ↩

-

See for example: USITC (2016), Cernat et al. (2018) and Breinlich et al. (2016) ↩

-

See for example: ILO (2016). ↩

-

See for example: Caliendo and Parro (2015) and Trefler (2006). ↩

-

For example, the UK is rated as having the 5th most efficient labour market in the world in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, 2016-17, behind only Switzerland, Singapore, Hong Kong and the United States. ↩

-

A purchasing power parity (PPP) adjustment has been applied to GDP figures. This adjustment accounts for differences in prices between 2 countries, such that the same GDP (on a PPP basis) would allow consumers to buy the same basket of goods in both countries ↩

-

Note that this figure is taken from the World Bank Development Indicators dataset and therefore does not exactly match the ONS figure of 62% quoted above ↩

-

Office for National Statistics, UK Trade (March 2018). ↩

-

Office for National Statistics, Foreign Direct Investment Involving UK Companies, 2016. Outward investment. ↩

-

Office for National Statistics, Foreign Direct Investment Involving UK Companies, 2016. Inward investment. ↩

-

Tariff average calculated using simple average of applied tariffs in 2016. Ad-valorem equivalents calculated for specific taxes. Note: Specific taxes are taxes applied per unit of good sold rather than as a proportion of overall value. ‘Ad valorem equivalents’ convert these specific taxes (e.g. £5 per kilo) into the tariff rate that would be payable if items taxed according to its value. Source: WITS database; EU tariff schedule used for the UK ↩

-

Defined here as Harmonised System (HS) sections ↩

-

Currently determined by the EU tariff schedule ↩

-

‘Ad valorem equivalents’ convert these specific taxes (e.g. £5 per kilo) into the tariff rate that would be payable if items taxed according to its value. Source: WITS database; EU tariff schedule used for the UK ↩