Technical report on the impacts of the trial

Updated 17 May 2022

Applies to England

DWP Research Report No. 988

A research report carried out by research consortium led by ICF on behalf of Department for Work and Pensions /Department of Health and Social Care (Employers, Health and Inclusive Employment directorate).

© Crown copyright 2021.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit The National Archives or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected].

If you would like to know more about DWP research, please email: [email protected]

First published July 2021.

ISBN: 978-1-78659-263-7

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Acknowledgements

This study was commissioned by the joint Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health and Social Care Work and Health Unit. We are particularly grateful to Pontus Ljungberg, Sian Moley, Lyndon Clews, Sarah Honeywell, Caroline Floyd, Rachel Shanahan, David Johnson, Mark Langdon, Anna Bee, Craig Lindsay and members of the DWP Policy Psychology Division for their guidance and support throughout the study.

Dr Adam P. Coutts would like to thank the Health Foundation for the 3-year fellowship (Grant ID – 1273834) which enabled him to conduct the research. Many thanks to Liz Cairncross at the Health Foundation who provided support and advice throughout the fellowship.

We would also like to thank the Jobcentre Plus staff, Group Leaders, provider representatives and individual benefit claimants who gave their time to participate in the fieldwork.

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions, Department of Health and Social Care, or any other government department.

Author’s credits

This report was prepared by Caroline Bryson and Dr Susan Purdon of Bryson Purdon Social Research.

Glossary of terms

| Active Labour Market Policy | Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) aim to increase the employment opportunities for job seekers and improve matching between jobs (vacancies) and workers (i.e. the unemployed). In so doing ALMPs may contribute to reducing unemployment and benefit receipt via increased rates of employment and economic growth. |

|---|---|

| Active learning techniques | Active learning techniques are based on actively involving participants in a learning activity rather than just requiring them to passively listen. |

| Carer’s Allowance | Carer’s Allowance (CA) is the main welfare benefit for carers and was formerly known as the Invalid Care Allowance. |

| Caseness | A person is described as having suggested case level anxiety or depression if their scores on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scales suggests they would exceed the ‘caseness thresholds’ used by Improved Access to Psychological Therapies. Diagnosis of anxiety and depression respectively would be based on a clinical interview and would take account of additional evidence, to which the GAD and PHQ scores may contribute. |

| Cost Benefit Analysis | A cost benefit analysis (CBA) examines all the costs and benefits of the intervention and quantifies them in monetary terms as far as possible, in order to examine the balance of costs and benefits. |

| Disability Employment Advisor | Disability Employment Advisors (DEAs) are people employed by Jobcentre Plus to support and upskill Work Coaches and other members of jobcentre staff to deliver tailored advisory services to disabled people. |

| Effect size | An effect size is the difference between the mean for the 2 groups (for example, the intervention and control groups in a randomised control trial) divided by the overall standard deviation. |

| Employment and Support Allowance | Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) is a benefit for people who have an illness, health condition or disability that affects how much they can work. ESA offers financial support if people are unable to work, and personalised help so that people can work if they are able to. |

| Financial strain | Financial strain refers to when an individual’s financial outgoings start to exceed their income to a degree that psychologically threatens their sense of self, identity, relationships and/or self-esteem. |

| General self-efficacy | General self-efficacy is the strength of an individual’s belief that they are effective in handling life situations. |

| Group Leader | Group Leaders are the individuals who delivered the Group Work course, using active learning techniques, to participants. |

| Group Work | Group Work is a course designed to enhance self-efficacy, self-esteem and social assertiveness among those looking for paid work. It aims to prevent the potential negative mental health effects of unemployment and help unemployed people back into work. The course is the application of JOBS II model, originally developed by the University of Michigan, in the UK labour market. |

| Impact on Participants | Impact on Participants (IoP) refers to the analysis of the impact of an intervention based on comparing outcomes for individuals who participated in the intervention with a matched comparison group of individuals who did not. |

| Income Support | Income Support (IS) is an income-related benefit for people who have no income or are on a low income, and who cannot actively seek work. It is mainly for people who cannot seek work due to childcare responsibilities. |

| Initial Reception Meeting | All Group Work participants were invited to an Initial Reception Meeting (IRM) which preceded the course itself. The IRM was designed as an opportunity for participants to meet the Group Leaders who would deliver their course and learn more about what it would involve. |

| Intention to Treat | Intention to Treat (ITT) refers to the analysis of the impact of an intervention based on comparing outcomes for all individuals who were offered the opportunity to participate in the intervention with a control group of individuals who were not offered this opportunity. |

| Jobcentre Plus | Jobcentre Plus (JCP) is a brand under which the DWP offers working-age support services, such as employment advisory services. In the context of this report, ‘jobcentre’ refers to the physical premises in which Jobcentre Plus services are offered. |

| JOBS II | JOBS II is the course originally designed by the University of Michigan, and the Group Work course is the application of JOBS II in the UK. |

| Job-search self-efficacy | Job-search self-efficacy is the strength of an individual’s belief that they have the skills to undertake a range of job-search tasks. |

| Jobseeker’s Allowance | Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) is an unemployment benefit for people who are actively looking for work. |

| Latent and Manifest Benefits | Latent and Manifest Benefits (LAMB) are material and psychosocial benefits associated with being in work such as social interaction, social support, activity, identity, collective purpose, self-worth (Latent benefits) and income (Manifest). |

| Mastery | The mastery outcome was a composite measure taking into account scores on job search self-efficacy, self-esteem and locus of control indexes. It was designed to be a measure of someone’s emotional and practical ability to cope and take on particular situations. |

| Mental Health Issues | Mental Health Issue is a broad term that includes those who have: deteriorating mental health (for example, related to the experience of unemployment); elevated but not clinical levels of a symptom; mental health conditions; or are post-treatment; have symptoms but may not recognise they have a condition; or are aware of their condition/ situation but choose not to disclose. Many individuals with Mental Health Issues are found to struggle with their job search. |

| Psychosocial | Psychosocial indicators concern psychological and social factors that can influence health and wellbeing outcomes. Typical examples of such indicators include social support, employment status, job quality, poverty and marital status. |

| Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy is the strength of an individual’s belief that they have the skills to undertake a task and achieve an outcome. |

| Standard deviation | Standard deviation is a statistical measure of how much or how little all values for a group vary from the overall mean for the group. A low standard deviation indicates that the values tend to be close to the mean, while a high standard deviation indicates that the values are spread out over a wider range. |

| Statistical significance | A statistic derived from a study, such as the difference between 2 groups, is said to be statistically significant if the size of that statistic has only a low probability of arising by chance alone. The probability of a statistic of that size occurring by chance alone is termed the ‘p-value’. By convention, if the p-value is less than 0.05 then it is stated that the statistic is ‘significant’. |

| Universal Credit | Universal Credit (UC) is an in and out of work benefit designed to support people with their living costs. Most new claims by people with a health condition or disability are now made to UC. |

| Well-being | Wellbeing is an individual’s self-report as to whether they feel they have meaning and purpose in their life, and includes their emotions (happiness and anxiety) during a particular period. |

| Work Coach | Work Coaches are frontline Jobcentre Plus staff based in jobcentres. Their role is to support benefit claimants into work through work-focused interviews. |

| Work and Health Unit | The Work and Health Unit (WHU) is a joint unit between the Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health and Social Care. It leads on the Government’s strategy to support working-age disabled people or those with long-term conditions, to access and retain good quality employment. |

| Zelen design | The Zelen design is randomised control trial methodology in which randomisation is applied before any potential beneficiaries are informed of the possibility of participating in the intervention being trialed. Only those randomised into the experiment group are informed of the opportunity of participating. |

Abbreviations

| ALMP | Active Labour Market Policy |

| CA | Carer’s Allowance |

| CBA | Cost Benefit Analysis |

| CV | Curriculum Vitae |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| DLA | Disability Living Allowance |

| DWP | Department for Work and Pensions |

| ESA | Employment and Support Allowance |

| FIOH | Finnish Institute of Occupational Health |

| GAD | Generalised Anxiety Disorder |

| GSE | General Self-Efficacy |

| GW | Group Work/JOBS II |

| IoP | Impact on Participants |

| IRM | Initial Reception Meeting |

| IS | Income Support |

| ITT | Intention to Treat |

| JCP | Jobcentre Plus |

| JSA | Jobseeker’s Allowance |

| JSSE | Job Search Self-Efficacy |

| LAMB | Latent and Manifest Benefits |

| ONS | Office for National Statistics |

| pp | Percentage Point |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PIP | Personal Independence Payment |

| RCT | Randomised Control Trial |

| UC | Universal Credit |

| UCLA | University of California, Los Angeles |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| WHU | Work and Health Unit |

Executive Summary

Aims of the Group Work trial

Group Work is a 20-hour job search skills workshop comprising 5 four-hour sessions delivered over the course of a working week designed to enhance self-efficacy, self-esteem and social assertiveness among those looking for paid work. Delivered by third party contractors, and using training on job search to help participants feel competent and confident in their abilities to look for and find paid work, Group Work aims to prevent the potential negative mental health effects of unemployment and help unemployed people back into work, as well as strengthening their resilience to setbacks that they may face in the process of applying for jobs.

Group Work is a trial of the JOBS II programme, which was originally developed in the United States by the Michigan Prevention Research Centre (MPRC) at University of Michigan. It has since been adapted and trialled in a number of countries. Between January 2017 and March 2018, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Joint Work and Health Unit undertook a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT), to test the potential effectiveness of the JOBS II intervention in a UK labour market context, targeting benefit claimants[footnote 1] who were struggling with their job search and/or were feeling low or anxious and lacking in confidence about their job search. Work Coaches were trained to recognise benefit claimants who were likely to benefit from the course based on these criteria. Over the course of the trial, 2,596 benefit claimants attended the Group Work course. Compared to the international trials, the UK trial was considerably larger in terms of the number of people included, and it covered a broader range of people, with no restrictions being set in terms of unemployment duration. The recruitment process in the UK was also very different, with all those deemed eligible being included, whereas in the international trials only those stating an interest in taking part were included.

The primary research question for the UK impact evaluation is whether Group Work improves employment, health and wellbeing outcomes for job seeking benefit claimants struggling with their job search. The impact evaluation addressed whether Group Work has a statistically significant positive impact on:

- entry into paid employment: The evaluation measures the impact of Group Work after 6 and 12 months on the percentage of people being in any paid work, as well as the percentage of those working 30 or more hours per week and receipt of unemployment-related benefits. It also looks at the type of work that people enter, measuring the impact of Group Work on people being in a job earning £10,000 or more per year, and on people being in a job with which they are satisfied

- people’s job search activity: Does Group Work have an impact on the type and level of job search activity that people are doing, including the number of CVs and applications they submit and their experience of doing work placements, voluntary work and/or training?

- people’s belief they have the skills to look for and find work: Does Group Work have an impact on people’s levels of self-efficacy and job search self-efficacy? Does it impact on their confidence in finding work and/or in the relevance of their own qualities and experience?

- wellbeing: Does Group Work have an impact on people’s levels of wellbeing, measured in terms of life satisfaction, happiness, self-worth, anxiety and loneliness, and their perceptions of the psychological and financial benefits of being in work?

- mental health: Does Group Work have an impact on people’s levels of anxiety, depression and wellbeing according to clinical measures?

- overall health: Does Group Work have an impact on the prevalence of self-reported health issues or on people’s use of health services?

In addition to measuring the impact of Group Work across the target population, a further aim of the impact evaluation has been to look for differential impacts across different population groups in line with the aims of the course and evidence from other JOBS II trials (where, notably, those with lower levels of self-efficacy and those with, or at higher risk of having, anxiety, depression or poor mental well-being). In other words, the analysis addresses the question of who benefits most from the course and whether the course is more effective in improving the outcomes of some population groups over others.

The impact evaluation

The impact evaluation was conducted as part of a wider programme of research for the Group Work project conducted by a consortium led by ICF, involving Bryson Purdon Social Research LLP (BPSR), IFF Research, Professor Steve McKay of the University of Lincoln, Dr Clara Mukuria of the University of Sheffield and Dr Adam Coutts of the University of Cambridge. This technical report details the methodology of, and findings from, the impact evaluation. It forms part of a suite of 3 technical reports from the evaluation, one per strand – impact evaluation, process evaluation and cost benefit analysis. A synthesis report integrates the findings from the 3 strands and provides commentary on their policy and practice implications.

Within the Zelen-designed RCT[footnote 2], eligible benefit recipients were randomly allocated either into a group offered the Group Work course or into a control group. The outcomes of trial participants were tracked from ‘baseline’[footnote 3] for 12 months, with data on their outcomes collected to measure the impact of the Programme 6 and 12 months after baseline using both administrative data and survey data collected on a sub-sample.

Those offered the course could opt to attend or decline to do so. In the event, only 22% of those offered the course went on to attend, with those most likely to do so being those reporting lower general or job-search self-efficacy, lower life satisfaction, lower levels of depression[footnote 4], the longer-term unemployed, and those who were older and male.

In line with the design of the trial, the original intention had been to measure the impact of Group Work among all those offered the course (an Intention-to-Treat (ITT) analysis) – that is, comparing the combined outcomes of those who attended the course (course participants) and those who declined (course decliners) against those not offered the course (the control group). With the achieved 6-month sample sizes, the size of impact needed for statistical significance on a binary (percentage) outcome is around 5 percentage points. That is, the difference between the offered Group Work group and the control group needs to be at least 5 percentage points.[footnote 5] With the sample sizes achieved at the 12 month survey the size of impact needed for statistical significance is around 7 percentage points.[footnote 6] However as, only 22% of those offered it participated on the course, the ability to detect impacts of this size is enormously reduced. Therefore, this report focuses mainly on the impacts of Group Work on course participants (an Impact on Participants (IoP) analysis). See Section 2 for more discussion on the methodology.

Headline findings

Overall, when looking at the impacts on all those offered the course (the ITT analysis), statistically significant positive impacts are detected on a small number of mental health, wellbeing and self-efficacy measures after 6 months. However, these statistically significant impacts are no longer in evidence after 12 months. When focusing on course participants (IoP), there are a wider range of significant positive impacts at 6 months across a range of mental health, well-being and self-efficacy measures, as well as on measures of confidence in finding paid work. Moreover, there is a pattern of positive but not statistically significant differences between the outcomes of participants and the matched comparison group. As with the ITT analysis, in the main, there are no longer statistically significant impacts at 12 months, although the non-significant differences between participants and the matched comparison group are still positive. The impacts which remain statistically significant at 12 months are that course participants were more likely than the matched comparison group to have higher levels of job search efficacy and higher self-reported levels of happiness. Group Work appeared to be most effective for those with lower levels of self-efficacy and higher levels of anxiety and depression before they start the course. There are a wide range of statistically significant positive impacts for these groups, sustained 12 months after baseline. Importantly, although there is no statistically significant evidence that Group Work impacts entry into paid work either across the whole trial population (the ITT analysis) or among all course participants (the IoP analysis), Group Work does appear to have a statistically significant impact on employment levels among those with greater mental health and self-efficacy issues prior to the course, broadly in line with the international evidence from other JOBS II trials. Importantly, there is no evidence of any negative impacts of attending a Group Work course.

Impacts across the trial population (ITT)

Overall, when looking at the impacts on all those offered the course (the ITT analysis), statistically significant positive impacts are found on a small number of mental health, wellbeing and self-efficacy measures after 6 months. However, these statistically significant impacts are no longer in evidence after 12 months.

In summary:

- there is no statistically significant evidence from the ITT analysis that Group Work impacts on entry into work[footnote 7] or on job search activity

- however, there is some significant evidence 6 months after baseline of Group Work positively impacting on levels of job search capability. Those offered Group Work were significantly more likely than those in the control group to have higher levels of general self-efficacy (59% compared to 54%) and to agree with a statement that ‘my experience is in demand’ (59% compared to 53%). However, this impact is not sustained 12 months after baseline. The difference between the job search self-efficacy scores of those offered and not offered Group Work were close to statistical significance 6 months after baseline (56% compared to 50%). However, no statistically significant impacts were found across a range of other job search confidence questions including a measure of confidence in finding work within the next 13 weeks

- using the World Health Organisation-Five Well-being Index (WHO-5) to identify those with likely depression or poor wellbeing, 6 months after baseline those offered Group Work had significantly better scores than those in the control group (a mean score of 12.2 out of 25 compared to 11.4). However, this statistically significant impact is not sustained 12 months after baseline. However, there is no consistent evidence from the ITT analysis that the offer of Group Work impacts on levels of anxiety or depression (measured using clinical standardised scales PHQ-9 and GAD-7)[footnote 8], or on overall self-perceived health or use of health services[footnote 9]

- looking across a range of wellbeing measures (including levels of life satisfaction, feeling worthwhile, happiness and loneliness), little statistically significant evidence is found of impacts on those offered Group Work

Impacts on Group Work course participants (IoP)

When comparing the 6-month outcomes of Group Work course participants with those of a matched comparison group drawn from the control group (i.e. an ‘Impact on Participant’, or IoP, analysis), there are a wider range of statistically significant positive impacts at 6 months than the ITT analysis across a range of wellbeing and self-efficacy measures, as well as on measures of confidence in finding paid work. However, as with the ITT analysis, in the main, these differences narrow after 12 months and, whilst remaining positive, are no longer statistically significant.

In summary:

- there are positive percentage point differences between course participants and the matched comparison group in terms of being in paid work, including measures of any work, full-time work, earnings levels and job satisfaction[footnote 10] although they are not large enough to reach statistical significance

- there is positive, but largely non-statistically significant, evidence of Group Work participants doing more job search (including looking for work, responding to vacancies and doing voluntary work, placements or training) than the matched comparison group. However, the only outcome for which there is a significant impact of attending Group Work is on the number of CVs that a participant had submitted in the previous fortnight. At 6 months, 28% of course participants had submitted ten or more CVs in the previous 2 weeks compared to 16% of the matched comparison group. The pattern is similar, and still statistically significant, at 12 months, with 26% of course participants submitting ten or more CVs compared to 18% of the matched comparison group

- Group Work appears to be effective in moving people towards work, increasing people’s belief in their ability to enter work. Six months after baseline, course participants reported a level of belief in their ability to find work not apparent among the matched comparison group across a range of measures. Six months after baseline:

- course participants were statistically significantly more likely than the matched comparison group to rate as having higher levels of general self-efficacy (60% compared to 47%). In other words, 6 months after the course, participants were more likely to perceive themselves as being able to effectively handle situations than their matched comparison group

- the proportion of course participants who reported higher levels of job search self-efficacy is also significantly different to the proportion among the matched comparison group (58% compared to 36%), with this significant impact still evident 12 months after baseline

- the percentage of course participants agreeing strongly or agreeing about the value of their personal qualities was significantly higher 6 months after baseline than the percentage in the matched comparison group. 70% of course participants and 59% of the matched comparison group agreed or agreed strongly that “my personal qualities make it easy to get a new job”

- likewise, 61% of course participants compared to 46% of the matched comparison group agreed or agreed strongly that “my experience is in demand in the labour market”

- course participants were also significantly more likely to be confident that they would find work within the next 13 weeks (40% compared to 27% of the matched comparison group)

Although positive differences between the 2 groups are sustained after 12 months, the only findings which remain statistically significant are levels of job search self-efficacy and the number of CVs being submitted by the 2 groups.

- there is statistically significant evidence of Group Work positively impacting on levels of mental health. Using the WHO-5 index, course participants were significantly less likely than the matched comparison group to score as having likely depression or poor wellbeing (49% compared to 59%) 6 months after baseline, although this is not sustained after 12 months. The PHQ-9 depression scale identified the same pattern of positive results, but not at a level that reached statistical significance. The differences in the proportions of participants and the matched comparison group whose scores suggest them having suggested case-level anxiety[footnote 11] using the standardised GAD-7 anxiety scale, were very close to statistical significance[footnote 12]

- moreover, across a range of wellbeing measures capturing life satisfaction, feeling life is worthwhile, happiness, loneliness, and perceptions of the value of employment, there are statistically significant positive impacts of Group Work on participants’ levels of wellbeing at 6 months. However, with the exception of levels of happiness, none of these impacts remain significant 12 months after baseline. 6 months after baseline:

- on the ONS life satisfaction measure, just under half (48%) of the course participants reported that they were satisfied with their lives compared to 34% of the matched comparison group

- using the ONS measure of the extent to which someone feels their life is worthwhile, just over half (54%) of the participants perceived life as being worthwhile compared to 38% of the matched comparison

- on the ONS measure of happiness, just over half (55%) of the course participants rated themselves as happy compared to 37% of the matched comparison group

- course participants were less likely than the matched comparison group to rate as lonely on the UCLA Loneliness Scale (46% compared to 55%)

- the LAMB scale measures someone’s self-perception of their psychosocial environment such as social support, activity, time structure and routine.[footnote 13] Course participants were more likely than the matched comparison group to have a positive perception of their psychosocial environment. On the standard 4-category measure which captures an individuals perceived psychological and social benefits to being employed (where a lower score denotes a better LAMB score), 15% of course participants scored in the lowest (best) category compared to 7% of the matched comparison group

Differential impacts across sub-groups of course participants (IoP)

Strong evidence was found, broadly in line with the international literature, that Group Work is most effective for those with lower levels of self-efficacy and those whose depression and anxiety levels at baseline suggest that they might receive a clinical diagnosis.

Course participants and the matched comparison group were divided into those with lower and higher levels of general self-efficacy at baseline (see Chapter 3 for more detail on how these groups are defined). Six months after baseline, course participants with lower baseline general self-efficacy had statistically significantly better outcomes than their matched comparison group in relation to being in paid work, in full-time paid work, their levels of general and job search self-efficacy, their wellbeing and their anxiety levels. With the exception of being in paid work, all of these statistically significant impacts are sustained 12 months after baseline. However, among those with higher levels of general self-efficacy, Group Work appeared to have very little impact. Nonetheless, there was a statistically significant positive impact (at 6 months, but not at 12 months) on levels of job search self-efficacy, and no evidence of the course having any negative impacts.

The pattern is very similar when course participants and the matched comparison group are divided into those with suggested case level[footnote 14] anxiety at baseline and those who did not. Again, Group Work is found to be effective in improving the 6 month outcomes of those with suggested case level anxiety at baseline across the same range of outcomes, whilst the only significant impact for those with lower baseline anxiety scores was on their levels of job search self-efficacy. Twelve months after baseline, among those with suggested case level baseline anxiety, course participants were significantly more likely to be in paid work of 30 hours or more and to have higher levels of general and job search self-efficacy.

Lastly, course participants and the matched comparison group are split into those whose PHQ-9 score suggested case level depression[footnote 15] at baseline and those whose score did not, there is similar evidence, but statistically significant on fewer outcomes, that Group Work is more effective for those with higher levels of depression. There is considerable overlap between anxiety and depression, so this consistency of evidence is to be expected. Among those with suggested case level depression at baseline, there are significant impacts - 6 and 12 months after baseline - on their levels of general and job search self-efficacy, and depression/wellbeing (as measured by the WHO-5 scale). Group Work appears to have very little impact on those who do not exhibit case level baseline depression. The only 6-month outcome on which there is a significant impact of Group Work among those with lower levels of baseline depression is job search self-efficacy.

Concluding comments

Low take-up of the Group Work course made it highly unlikely that statistically significant impacts could be identified across all those offered the course (as per the original ITT design). However, under the IoP analysis, where the 6 and 12-month outcomes of course participants are compared to a matched comparison group, there is some evidence of Group Work having an impact at 6 months. Although it did not appear to impact on employment rates, its ability to impact on mental health, levels of job search self-efficacy, participant confidence and a wider range of wellbeing outcomes suggests that the course is effective in these respects. Moreover, no negative impacts of Group Work on course participants were detected. However, as these positive impacts tend to remain but not be statistically significant 12 months after baseline, it suggests that some further intervention might be required to capitalise on these early impacts.

A key finding from this evaluation is the differential impact that Group Work appeared to have on sub-groups of participants with different starting points, and is supported by evidence from previous JOBS II trials. It was most effective for those with lower starting levels of general self-efficacy and poorer mental health, where there are statistically significant impacts - importantly, often sustained after 12 months - on employment and mental health outcomes, self-efficacy and wellbeing. Although this will no doubt give pause for thought about whether the course should be more targeted, it is important to consider whether the same impacts would have been found if the dynamics of the course were changed by having a greater proportion of attendees with these potential challenges to entry into work. This is further discussed in the process evaluation (Knight et al., 2020a) and synthesis reports (Knight et al., 2020b).

1. Overview

1.1. Overview

Group Work is a 20-hour job search skills workshop designed to enhance self-efficacy, self-esteem and social assertiveness among those looking for paid work. Using training on job search to help participants feel competent and confident in their abilities to look for and find paid work, it aims to prevent the potential negative mental health effects of unemployment and help unemployed people back into work. It is a UK version of the JOBS II programme that was originally developed in in the United States by the University of Michigan and since been trialled in a number of countries.

Group Work is one of several interventions being trialled by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Joint Work and Health Unit (WHU) to build a strong evidence base of what interventions work best to help those with health issues move into or retain work (see van Stolk et al., 2014, for the report which recommended the testing of JOBS II in the UK). The WHU undertook a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT), to test the potential effectiveness of the JOBS II intervention in a live UK labour market context, targeting benefit claimants struggling with their job search and/or feeling low, anxious and lacking in confidence about aspects of their job search. The evaluation of the Group Work Trial was conducted by a consortium led by ICF, involving Bryson Purdon Social Research LLP (BPSR), IFF Research, Professor Stephen McKay of the University of Lincoln, Dr Clara Mukuria of the University of Sheffield and Dr Adam Coutts of the University of Cambridge. The evaluation comprised 3 main strands:

- an impact evaluation, drawing on survey data collected for random sub-samples of the trial participants and DWP administrative data, measuring the impact of Group Work after 6 and 12 months

- a process evaluation focusing on the set up and running of the trial as well as the perceptions of course participants, and those declining to participate, in Group Work

- a cost benefit analysis, comparing the costs of running the course against the monetary gains of any improvements in participants’ outcomes

ICF conducted the process and cost benefit analysis strands. BPSR conducted the impact analysis based on DWP administrative data and a longitudinal survey of trial participants which was conducted by IFF Research (which also included participant perception questions which formed part of the process evaluation). Dr Adam Coutts, whilst on a research placement with DWP, was directly involved in the design and commissioning of the trial and the evaluation and conducted a programme of observation and ethnographic research with programme providers and participants.

This technical report details the methodology of and findings from the impact evaluation. It forms part of a suite of 3 technical reports from the evaluation, one per strand (Knight et al., 2020a; Rayment et al., 2020)). A synthesis report integrates the findings from all 3 strands, along with commentary on their policy and practice implications (Knight et al., 2020b).

In the Zelen-based RCT (see Section 2.3 for more detail), eligible benefit recipients were randomly allocated either into a group offered the Group Work course or into a control group. Those offered the course could opt to attend the course or decline to do so. The outcomes of trial participants were tracked from ‘baseline’[footnote 16] for 12 months, with data on their outcomes collected to measure the impact of the Programme 6 and 12 months after baseline using both administrative and survey data.

In line with the design of the trial, the original intention had been to carry out an Intention-to-Treat (ITT) analysis to measure the impact of Group Work among all those offered the course – that is, comparing the combined outcomes of those who attended the course (course participants) and those who declined (course decliners) against those not offered the course (the control group). The rationale for this was that the RCT was designed to test the effect of a voluntary course and, therefore, its overall impact should necessarily include those who did not choose to take it up. However, only 22% of those offered the course went on it. As a result, the ability to detect an impact of the Programme based on an ITT analysis is enormously reduced (see Section 6.1). Therefore, while the ITT analysis is reported in Chapter 5, the main focus is on the impacts of Group Work on course participants (Impacts on Participants (IoP), reported in Chapters 6 and 7). Although this moves away from the original trial design, it was deemed a fairer test of the effectiveness of the course. A range of steps have been taken to ensure that, as far as the data will allow, the outcomes of course participants are compared against a matched comparison group who, at baseline, very closely resembled course participants (see Section 6.2).

1.2. Aims of the impact evaluation

The WHU’s trial of Group Work targeted claimants of Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA), Employment Support Allowance (ESA), Universal Credit Full Services (UC) and Income Support (IS) (Lone Parents with child(ren) aged 3 and over) who were struggling with their job search and/or feeling low or anxious and lacking in confidence about their job search. The overall aim of the impact evaluation has been to measure the effectiveness of Group Work within a live UK policy context among this target group. The target population for the Group Work trial was broader than for several other international evaluations of JOBS II (for instance, including those with both short and longer-term periods of unemployment). Compared to other trials, Group Work also included a much larger proportion of people who had no experience of paid employment (see Section 2.2 for more detail).

The primary research question for the impact evaluation is whether Group Work improves employment, health and wellbeing outcomes for job seeking benefit claimants struggling with their job search. The full range of outcome measures is described in Chapter 3, but in summary, the research questions for the impact evaluation are:

Does Group Work have a statistically significant positive impact on:

- entry into paid employment: The evaluation measures the impact of Group Work after 6 and 12 months on the percentage of people being in any paid work, as well as the percentage of those working 30 or more hours per week. It also looks at the type of work that people enter, measuring the impact of Group Work on people being in a job earning £10,000 or more per year, and on people being in a job with which they are satisfied

- people’s job search activity: Does Group Work have an impact on the type and level of job search activity that people are doing, including the number of CVs and applications they submit and their experience of doing work placements, voluntary work and/or training?

- people’s belief they have the skills to look for and find work: Does Group Work have an impact on people’s levels of self-efficacy and job search self-efficacy? Does it impact on their confidence in finding work and/or in the relevance of their own qualities and experience?

- wellbeing: Does Group Work have an impact on people’s levels of wellbeing, measured in terms of life satisfaction, happiness, self-worth, anxiety and loneliness, and their perceptions of the psychological and financial benefits of being in work?

- mental health: Does Group Work have an impact on people’s levels of anxiety, depression and wellbeing according to clinical measures?

- overall health: Does Group Work have an impact on the prevalence of self-reported health issues or on people’s use of health services?

In addition to measuring the impact of Group Work across the target population, a further aim of the impact evaluation has been to look for differential impacts across different population groups in line with the aims of the course and evidence from other JOBS II trials (where, notably, those with lower levels of self-efficacy and those at higher risk of mental health problems). In other words, the analysis addresses the question of who benefits most from the course and whether the course is more effective in improving the outcomes of some population groups over others.

1.3. Report outline

This technical report is structured as follows:

- Chapter 2 outlines the Group Work course, detailing the RCT design used to test the impact and including a summary of international trials of JOBS II

- Chapter 3 describes the outcomes used to measure the impact of Group Work

- Chapter 4 provides a profile of the trial population, and examines the factors that are correlated with take-up of the course

- Chapter 5 details the methodology and findings from the ITT analysis, that is, the impact of Group Work at 6 and 12 months among all those offered the course

- Chapter 6 details the methodology and findings from the IoP analysis, that is, the impact of Group Work at 6 and 12 months among those who attended the course

- Chapter 7 reports on the impact of Group Work at 6 and 12 months among different population sub-groups of course participants (an IoP analysis)

- Chapter 8 provides concluding comments on the report findings

There is an amount of repetition within each chapter, so that each can, as far as is possible, be read as a stand-alone chapter. Those interested in the key findings should focus on Chapters 2, 6, 7 and 8.

The following appendices are included at the end of the report:

- non-response weighting (Appendix A)

- demonstration of balance between the 2 arms of the trial at randomisation and for those responding to the surveys at 6 and 12 months (Appendix B)

- propensity score matching (Appendix C)

- correlations between the outcome measures (Appendix D)

2. The Group Work trial design

2.1. The Group Work course

Group Work is a 20-hour group-based course delivered in 5 half-day sessions, averaging 4 hours a day, over the period of a working week. The course content focuses on job search skills. However, the underlying processes by which it is delivered are also designed to enhance the self-efficacy, self-esteem and social assertiveness of the participants to help unemployed job seekers with (or at risk of) mental health issues look for and find paid work:

The job-search skill content is used as a vehicle for helping participants feel competent and confident. It is this confidence that will be the true source of their success.

UK edition of JOBS II Manual

The course is led by trained facilitators using active learning techniques and aims to prevent the potential negative mental health effects of unemployment and help unemployed people back into work. During the trial, benefit claimants who agreed to attend the course were first invited to attend an Initial Reception Meeting (IRM) at which they met the facilitators and other participants and found out more about what the course would involve. Both the IRM and the full course were delivered at non-Jobcentre Plus venues by a third-party provider.

Group Work is the application of the JOBS II model, which was first developed in the United States by the University of Michigan and since trialled in a number of countries (see Section 2.2). It is one of a number of interventions being trialled by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Joint Work Health Unit (WHU) to build a strong evidence base of what interventions work best to help those with health issues move into or retain work.

For more information on how the course was set up and delivered, and course content see Knight et al. (2020a).

2.2. International trials of the JOBS II programme

The process report for this evaluation (Knight et al., 2020a) includes a summary of the international evidence from previous evaluations of JOBS II. Differences in trial populations and outcome measures make it hard to make direct comparisons with the Group Work trial. However, the summary here draws on the 2 trials which provide the most relevant for and comparable data to the UK trial, with Table 2.1 summarising trial designs in each case. Further detail on the UK trial is included in Section 2.3, with the findings for the US and Finnish trials being discussed here.

Table 2.1: Summary of the trial designs in the UK, United States of America and Finland

| Group Work (UK) Trial | USA Trial | Finnish Trial | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | Benefit claimants struggling with job search. No criteria set in terms of unemployment duration | Unemployed for less than 13 weeks | Unemployed or had received termination notice. No criteria set in terms of unemployment duration |

| Recruitment and random allocation | Zelen design. All those identified as eligible were included in the trial and randomly allocated. Those allocated to the intervention arm were then invited to take up the course. | Trial participants initially recruited by interviewers. Those interested were asked to complete a screening questionnaire. Only those screened in were randomly allocated. | Potential participants were contacted about the trial. Only those expressing interest were randomly allocated. |

| Numbers randomized | 16,193 | 1,801 | 1,261 |

| Take-up of the programme in the intervention arm | 22% | 54% | 70% |

| Range of outcomes collected | Employment; job-search activity; general self-efficacy; job-search self-efficacy; latent and manifest benefits; well-being; depression; anxiety; overall health. | Employment, financial strain; assertiveness; role and emotional functioning; job search self-efficacy; self-esteem; internal control orientation; mastery, depression; distress symptoms. | Employment, wage rate, job stability, job satisfaction; job-search intensity; psychological distress; and depressive symptoms. |

The initial JOBS II model developed in the United States by the University of Michigan was first tested in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Vinokur et al., 1995). That trial focussed on those unemployed for less than 13 weeks so in that respect alone is very different to the Group Work trial in the UK which included jobseekers with a range of lengths of unemployment (including half who report never having been in paid work) as well as those already in some form of paid work. Trial participants were recruited to the US trial by trained interviewers (again, a difference to the UK trial where Work Coaches were responsible for recognising benefit claimants who might benefit from the offer of Group Work) approaching potential participants while they waited in unemployment offices. Those meeting basic eligibility criteria were told about the programme and asked to complete a screening questionnaire. Those judged eligible based on their questionnaire responses were then randomly allocated to JOBS II or control group. The trial was designed to allow for a test of whether JOBS II was more, or less, effective for those at high risk of depression (relative to mild risk), and the trial actively over-represented those at high risk.

Of those allocated to JOBS II, 54% took up the programme. This is much higher than the take-up percentage for the Group Work trial, where the take-up rate was 22%. The exact reasons for this large difference between the 2 trials are unclear. It may reflect the fact that the JOBS II trial in the US recruited only those recently unemployed, or it may be a cultural difference. Another plausible explanation is that the recruitment by interviewers in Michigan prior to randomisation led to the exclusion of many of those who were simply not interested in participation.

The outcomes studied in the Michigan trial covered a similar range to those of the Group Work trial (depression, financial strain, assertiveness, distress symptoms, role and emotional functioning, job search self-efficacy, self-esteem, internal control orientation, mastery[footnote 17], and reemployment). However, the outcome scales used are generally not the same as those used in the Group Work trial, so direct comparison is not possible. The main findings from the United States JOBS II trial at 6-months were:

- the experimental group had significantly higher mastery scores than the control group

- those at high risk of depression were significantly more likely to be in work if they were in the experimental group rather than the control group, the impact being around 10 percentage points. There was no significant impact on employment for those at mild risk of depression

- the programme had a positive impact on measures of depression for those at high risk of depression, but no impact on those at mild risk of depression

The JOBS II programme has also been tested using a RCT design in Finland (Vuori et al., 2002). The Finnish trial recruited people from a longer-term unemployed population than the Michigan trial and is in that respect closer to the UK Group Work trial. However, the recruitment process was very different to the UK model. In Finland, potential participants were contacted, informed about the trial, and only those interested in taking part, agreeing to randomisation, and completing a baseline assessment questionnaire were included. This approach generated a much higher take-up rate of the programme for those allocated to the experiment group, at 70%. This recruitment approach provides a trial of JOBS II for a group of people who believe that the programme will benefit them and so are willing to engage. The impacts from such a trial are unlikely to be replicated in a trial with a broader population.

The outcomes collected in the Finnish trial are, again, similar to the Group Work outcomes in terms of their range, but the actual scales used are different. So, as with the Michigan trial, direct comparisons with the UK trial are generally not possible. The Finnish outcomes include: reemployment, wage rate, job stability, job satisfaction, job-search intensity, psychological distress (measured using the General Health Questionnaire), and depressive symptoms (measured using the Depression (DEPS) scale).

The Finnish trial found that at 6-months:

- there was no statistically significant impact on reemployment, but there was a positive significant impact on stable employment[footnote 18]; this impact was greatest for those unemployed for a ‘moderate’ amount of time (3 to 12 months). There was no statistically significant impact on the longer-term unemployed

- no statistically significant impacts on wage rates or job satisfaction were found

- there was a statistically significant positive impact on reduced psychological distress, with the impact being greatest for those at the greatest risk of depression at baseline. No statistically significant impact was detected on depressive symptoms

2.3. The Group Work trial design

The Group Work trial started in January 2017 and finished in March 2018, with 2,596 benefit claimants attending the Group Work course (with attending defined as starting but not necessarily completing). The trial operated in 5 Jobcentre Plus districts – Durham and Tees, Merseyside, Midland Shires, Mercia, and Avon, Severn and Thames, with one or 2 centrally located provider hubs (where the Group Work course was delivered) and a number of participating jobcentres in each district.

To be eligible for the trial, participants had to be struggling with their job search and/or feeling low or anxious and lacking in confidence about their job search, and in receipt of Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA), Employment Support Allowance (ESA), Universal Credit Full Services (UC) or Income Support (IS) (Lone Parents with child(ren) aged 3 and over). Benefit claimants who were doing some forms of paid work were still eligible for the trial if they were seeking further or different employment.

Work Coaches in the participating jobcentres were responsible for recognising benefit claimants who might benefit from Group Work, and were provided with training and a desk-based aid using these eligibility criteria (see Knight et al., 2020a for more detail). They administered an onscreen survey with these claimants. On completion of the survey (and regardless of the responses given), the benefit claimants were randomised into 2 unequally sized groups, the first of which was offered the opportunity to go on the course (the ‘intervention’ or ‘offered Group Work group’) and the second was not (the ‘control group’). 73% (n=11,900) of the trial participants were randomly assigned to the offered Group Work arm of the trial and 27% to the control group (n=4,293).[footnote 19] The control group were offered standard services, as appropriate, with no mention made of Group Work.

The Work Coaches introduced and explained the course to benefit claimants allocated to the offered Group Work arm and then carried out handovers to the provider in their district. Participation in Group Work was entirely voluntary.

At the point of randomisation, 45% of those offered the course agreed to attend the initial reception meeting (IRM) that preceded the course, with the proportion interested reducing over time. A third (34%) attended an IRM, whilst only 22% started the course (with attendance defined as starting the course). While the process report (Knight et al., 2020a) provides commentary on a range of reasons for this, from an impact perspective it is important to note that some of those initially interested may have later declined because they entered paid work before the course start.

The Group Work course was delivered by 2 third-party providers: one covering the Durham and Tees and Merseyside districts; and the other the Midland Shires, Mercia and Avon, Severn and Thames districts. Both providers had a Service Level Agreement with the DWP that benefit claimants would attend an IRM within 5 days of a referral and that they would start the full Group Work course within 15 days.

The trial adopted a single consent Zelen design (Torgerson and Roland, 1998). In accordance with this design, eligible benefit claimants were randomised into either the ‘offered Group Work’ arm or the control arm without obtaining prior informed consent. The single consent design means that only those offered Group Work were later informed that they were part of a trial and given the option of accepting or declining the intervention. Those in the control group were not offered Group Work but rather were offered the standard range of interventions or support through Jobcentre Plus.

The Zelen design made the trial operationally easier to administer for Jobcentre Plus Work Coaches. It allowed the Work Coach to have a fuller discussion if they knew the benefit claimant has been allocated to the intervention arm, as opposed to a Work Coach trying to recruit a benefit claimant into a trial in which they may be allocated to the control group. Where benefit claimants were indeed allocated to the control group, this had the potential to harm the working relationship between the claimant and the Work Coach.

The motivation for running the trial as a formal RCT, whether following a Zelen design or otherwise, was that it would give unbiased estimates of impact based on an Intention to Treat (ITT) analysis. Under this analysis, outcomes for all those assigned to the offered Group Work arm (irrespective of whether or not they take up the course) are compared to outcomes for those assigned to the control group. The randomisation should ensure that the 2 arms of the trial are ‘balanced’, in the sense that they will both have the same profile of people, apart from any randomly occurring differences. Any difference in outcomes that is statistically significant can then be confidently attributed to the Group Work offer. Table B.1 of Appendix B demonstrates the balance at the point of randomisation.

In part this ‘guarantee’ of balance is somewhat undermined because data on most outcomes have necessarily been collected by survey rather than via administrative systems (see Section 2.4 for more detail). The surveys are voluntary and there is potential for non-response bias. If there are differences in the response profile for the 2 arms of the trial this may introduce bias into the estimates of impact. Furthermore, the baseline data were not collected at the same time for participants relative to decliners and controls, with baseline data for participants being collected on Day 1 of the course and baseline data for decliners and the control group being collected a few months later (see Section 2.4). Steps have been taken to test for and minimise any bias attributable to these features. The survey data have been tested for non-response bias by comparing the profile of those responding to the 6 and 12 month surveys to the profile of all those randomised. Observed differences in the profile have been addressed by applying non-response weights. After applying these weights, there is no observable evidence of imbalance. The details are included in Appendices A and B.

2.4. Data used in the impact analysis

The impact of Group Work has been estimated using DWP administrative data on benefit receipt and a longitudinal survey of random samples of those from each arm of the trial.

The administrative data cover the full trial population, including receipt, and its monetary value, of JSA, ESA, IS, UC, Disability Living Allowance (DLA), Carer’s Allowance, State Retirement Pension, Pension Credit, Widow’s Benefit and Bereavement Benefit. The analysis focuses on receipt and monetary value of the benefits related to unemployment or low pay, namely JSA, ESA, IS and UC, at 3 points in time: at randomisation as well as 6 and 12 months after randomisation.

The survey data[footnote 20] used for the impact evaluation were collected at 4 points in time[footnote 21]:

- At the point of randomisation, using an online survey administered by the Work Coaches. Key demographics and scores from a sub-set of outcomes were collected at this point on the 16,193 people entering the trial.

- A baseline survey collected a richer set of outcome measures. For the 2,596 course participants, this survey of pre-course outcomes measures was administered by the Group Leaders on the first day of the course. A random sample of those who declined the course (the ‘decliners’, who form part of the ITT analysis) and a random sample of the control group were contacted by IFF to take part in a telephone survey - 2,559 decliners and 1,484 members of the control group took part in this baseline survey. It is important to note 2 key differences between the baseline survey for course participants and the other 2 groups. The first is the data collection mode (telephone compared to paper self-completion). Second, although the baseline survey for decliners and the control group is designed to provide comparable data to the pre-course outcomes for participants, the participant baselines were conducted around 3 weeks after randomisation (median=20 days, mean=38 days), while, for decliners and the control group, the average gap between randomisation and the baseline survey collection was almost 5 months (median=145 days, mean=143 days). The reasons for the delay for the decliners and control group were mainly down to sample management issues. Firstly, an interval of several weeks was needed after randomisation so that the decliners could be distinguished from participants, after which a period was needed for sample cleaning. Secondly, those sampled were written to in advance of being approached by IFF, giving them an opportunity to opt out of the surveys. As a result, these processes took several months.

- Six months after baseline: All those taking part in the baseline survey were invited to take part in a telephone survey 6 months later, repeating the outcome measures collected at randomisation and baseline. 744 of the course participants, 1,066 decliners and 648 control group members did so.

- Twelve months after baseline: All those taking part in the baseline survey were again invited to take part in a telephone survey 12 months later (regardless of whether or not they took part at 6 months), using the same set of outcome measures as at the 6-month survey. 593 of the course participants, 580 decliners and 427 control group members did so.

The survey data have been assessed for non-response bias and non-response weights applied. This stage involved a comparison between the survey respondents and all those randomised on a range of characteristics recorded either at the randomisation stage survey or in DWP administrative datasets. To allow for this comparison, the data used in this report had to be restricted to those consenting for their survey data to be linked to DWP administrative data. This reduces the 6-month sample sizes to 609 for participants, 887 for decliners and 533 for the control group. The sample sizes at 12 months reduces to 510 for participants, 580 for decliners and 362 for the control group. The details of the non-response weighting are included in Appendix A. With these 6-month sample sizes, and allowing for the fact that the 609 participants have to be weighted down so that they represent 22% of the offered Group Work arm, the size of impact needed for statistical significance on a binary (percentage) outcome is around 5 percentage points.[footnote 22] That is, the difference between the offered Group Work group and the control group needs to be at least 5 percentage points. With the sample sizes achieved at the 12 month survey the size of impact needed for statistical significance is around 7 percentage points.[footnote 23]

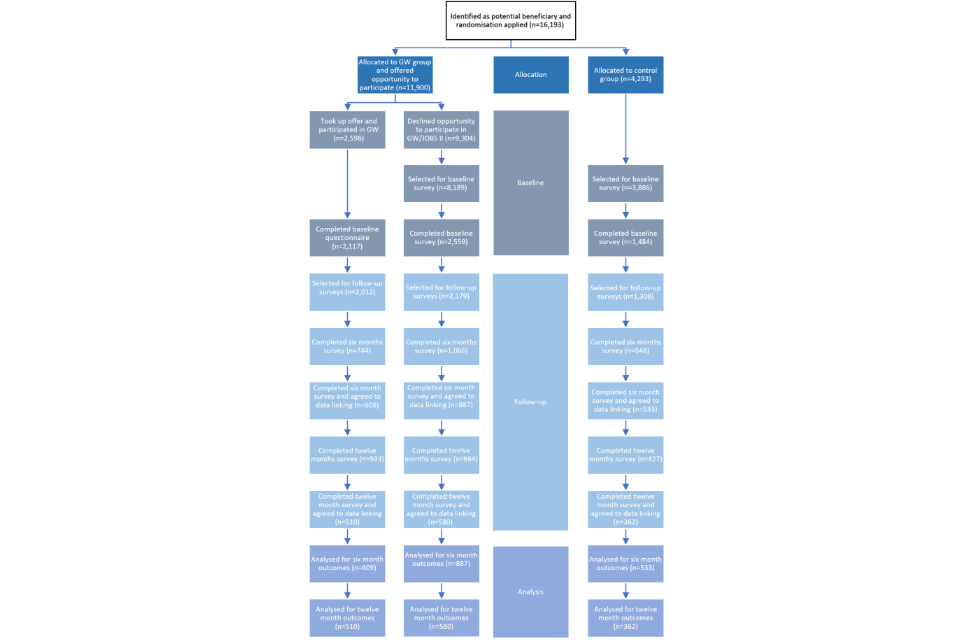

The trial design is summarised in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Flow diagram for the Group Work RCT

2.5. Table format, statistical tests and p-values

Most of the tables in this report use the same format. The tables present the results for each outcome at baseline or randomisation (see Section 2.4), 6 months after baseline and 12 months after baseline. Where available, randomisation data are reported, as this provides the most accurate measure of outcomes prior to being offered the course, collected at precisely the same time point for both arms of the trial. Where the outcome measure was not collected at the point of randomisation (the case for the majority of outcomes) the baseline outcome is reported, with each table making clear which data wave are reported. The tables present the randomisation and baseline outcomes for all those completing the 6-month survey, but the results are very similar for those completing the 12-month survey. For each survey wave, the percentage or mean score is shown for those in the offered Group Work group and for those in the control or comparison group. Where data are not available, this is shown in the table as 2 dots (..).

The tables show for each outcome the p-value significance level of the difference between the offered Group Work and control/comparison groups. The p-value is the probability of an observed difference being due to chance alone, rather than being a real underlying difference for the population. A p-value of less than 5% is conventionally taken to indicate a statistically significant difference (p<0.05). The p-values have been calculated in the complex samples module of SPSS and take into account the weighting of the data applied to address survey non-response biases– see Appendix A. Where the differences between the 2 groups are statistically significant (that is the p-value is less than 0.05), these are highlighted in red and with an asterisk. The term ‘statistically significant’ is often abbreviated in the text to ‘significant’. The text also includes discussion of impacts which are close to statistical significance using, as a rule of thumb, a p-value of less than 0.10.

A large number of statistical tests have been carried out and included in this report. No attempt has been made to allow for multiple comparisons, partly because the number of tests is so large, but also because the tests are not independent of one another (the same sample is used each time and the outcomes are correlated), so standard multiple comparison adjustments are not valid. It should be noted that there is a risk that some of the apparent significant differences may arise just by chance.

P-values are dependent on sample size. For any given observed difference, the smaller the sample size the larger the p-value. Because the survey sample size is larger at 6 months than at 12 months, the impacts have to be slightly larger at 12 months to reach significance.

The unweighted sample sizes are cited at the end of each table.

3. The outcome measures

3.1. Overview

Drawing on the aims of Group Work, the evaluation measures the impact of Group Work on a range of employment, job search, mental health and well-being outcomes collected in the four-wave longitudinal survey of the trial population. In addition, the impact of Group Work is measured using Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) administrative data on being on job search related benefits and on the monetary value of those benefits (see Section 2.3).

As described in Section 2.3, baseline survey measures were collected at 2 points in time among course participants, those who declined the course and the control group. Data on a subset of outcomes were collected at the point of randomisation but as the amount of data that could be collected at that point was necessarily limited by the time available in the Work Coach interview, a fuller set of outcomes was asked in the baseline survey. These same outcomes were repeated at 6 months and 12 months after the baseline. The impact on benefit receipt using administrative data draws on 3 time points: randomisation and 6 and 12 months after randomisation.

The tables in Sections 3.2. to 3.8 show which outcomes were asked at each data collection point, from randomisation to 12-month follow-up.

This chapter provides more detail on each of the outcome measures, including the points at which the data were collected, divided into:

- work-related outcomes (section 3.2)

- job search related outcomes (section 3.3)

- well-being outcomes (section 3.4)

- mental health outcomes (section 3.5)

- wider health outcomes (section 3.6)

The interconnectedness of a number of the mental health, health and wellbeing outcomes means that there is a relatively high level of correlation between the outcomes, demonstrated in Appendix D. This means that, to some extent, there is overlap in what different measures (for example, anxiety and depression; wellbeing and loneliness) are capturing.

3.2. Work-related outcomes

A core aim of Group Work is to help people enter paid employment if they are ready to do so. A secondary aim is to ensure the quality of any work that people take up.

The survey data is used to measure the impact of Group Work against the following work-related outcomes:

- currently being in paid work (currently working for an employer or self-employed or having done paid work within the previous 7 days)

- currently being in paid work of 30 or more hours a week (i.e. in full-time work)

- currently being in paid work that someone is satisfied with (‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ on a 5-point scale)

- currently earning above or below £10,000 per annum

The impact on receipt of Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA), Employment Support Allowance (ESA), Universal Credit (UC) or Income Support (IS) is also measured using administrative data, including the amount of these benefits received. Whilst not a measure of entry into work, with several of these benefits payable to those on low incomes, benefit receipt – and the value of those benefits – provide a rough proxy measure of the impact of Group Work in helping people into paid work, or paid work of higher hours or higher levels of pay.

Each of these outcomes were asked at the following time points. Unfortunately, course participants were not asked at the baseline survey whether they were in paid work and, thus, any details about any work they might have been doing at that point. However, eligibility for the course did not exclude benefit claimants in paid work.

Administrative data

| Randomisation | Baseline | 6-months after randomisation | 12-months after randomisation | 6-months after baseline | 12-months after baseline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receipt of JSA/UC/ESA/IS | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Value of JSA/UC/ESA/IS payments | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Survey data

| Randomisation | Baseline | 6-months after randomisation | 12-months after randomisation | 6-months after baseline | 12-months after baseline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In paid work | No | Decliners and control group only | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| In paid work 30+ hours a week | No | Decliners and control group only | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| In paid work that satisfies | No | Decliners and control group only | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| In paid work earning more or less than £10k pa | No | Decliners and control group only | No | No | Yes | Yes |

3.3. Job search-related outcomes

If someone has not entered employment as a result of attending a Group Work course, a positive outcome would still be evidence that someone is closer to entering work. The evaluation included a range of measures about people’s job search activity and propensity to look for work:

- levels of job search activity are measured using the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health Job Seeking Activity Scale (Revised). This 7-item job search activity scale measures the frequency with which individuals undertake key job search activities, for example contacting employers or searching for job vacancies on the internet. The original version of this measure was developed at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health (FIOH) (Vuori and Tervahartiala, 1994; Vuori and Vesalainen, 1999) and subsequently modified for use in the UK labour market. Modifications were made by Birkin and Meehan in 2004 and 2016, to include 2 additional items on internet-based job search and followed the format of the existing items. These changes were made following discussion with Professor Jukka Vuori. Survey respondents are given a list of job search activities - including looking for advertised job vacancies both online and at jobcentres or in newspapers and making speculative contacts to employers - and asked to say how often they had done this activity within the past 2 weeks (with response codes ranging from ‘not to all’ (1) to ‘every day’ (4)). Using the mean from the responses from the 7 items, a job search activity scale was created (a continuous variable running from 1 (no job search) to 4 (scoring ‘every day’ on all 7 items). Those scoring 1.01 to 2.29 are coded as ‘lower levels of job search activity’ job search and those scoring 2.3 or more are coded as ‘higher levels of job search activity’ job search. The higher and lower activity categories are derived from the baseline scores of the control group (with high and low split into 2 equally-sized groups), as the control group provides a representative picture of the eligible population. Those working 30 or more hours were not asked these questions, and therefore form a separate category in the outcome measure

- the Job Seeking Activity Scale also asks about number of vacancies applied for and CVs submitted. Respondents are categorised into those who applied for fewer or more than ten vacancies in the past 2 weeks. Likewise, they are categorised into those who submitted fewer or more than ten CVs in the past 2 weeks

- gaining relevant skills or experience is measured by 3 measures: whether someone has (a) attended training or courses; (b) done voluntary work and/or (c) attended work placements in the previous 6 months

Although the Job Seeking Activity Scale was asked at baseline, a large proportion of participants did not provide a response to a number of items on the scale. Therefore, it is not possible to use the baseline data for this variable. As a result, as none of the other variables were asked at the point of randomisation or at baseline, there is no ‘pre-programme’ job search measures.

Each of these outcomes were asked at the following time points:

| Randomisation | Baseline | 6-months | 12-months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of job search activity | No | No[footnote 24] | Yes | Yes |

| Vacancies applied for | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| CVs submitted | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Training or courses | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Voluntary work | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Work placements | No | No | Yes | Yes |

In addition, Group Work aspires to increase people’s confidence that they can enter work, and the evaluation therefore includes a number of measures aimed at capturing whether Group Work does have an impact on people’s perceptions that they could enter work:

- general self-efficacy is a broad measure of the strength of an individual’s beliefs that they are effective in handling life situations. The evaluation measured this using the 3 item General Self Efficacy Scale, originally developed for a study exploring whether self-efficacy predicts return to work following sickness absence (Labriola et al., 2007). Survey respondents are asked to score themselves using a 5-point scale from ‘always’ to ‘never’ on 3 statements about their confidence in dealing with situations and solving problems. A mean score is calculated across the 3 items, where 1 denotes high self-efficacy and 5 denotes low self-efficacy. The scores are also grouped into ‘higher self-efficacy (less than 2.34) or lower self-efficacy (2.34 or more). As with the job search activity scale, the high and low self-efficacy categories are derived from the baseline scores of the control group (with ‘high’ and ‘low’ split into 2 equally-sized groups)

- the Job Search Self Efficacy (JSSE) Index (Modified) is a 9-item measure of the strength of an individual’s belief that they have the skills to undertake a range of job search tasks. The JSSE gathers information about a key predictor of job search behaviours (Eden and Aviram, 1993; Kanfer and Hulin, 1985; Saks and Ashforth, 1999). It has been argued that job search self-efficacy is an important motivational factor which facilitates appropriate job search behaviour as well as providing a buffer against the deleterious effects of unemployment. The original 6-item JSSE Index was developed at the University of Michigan (Vinokur et al., 1995). This was subsequently modified for use in the UK labour market by Birkin and Meehan in 2014, following discussion with Professor Richard H Price. Three new items were added to address using IT for job search and work. For each of the nine items – including writing a good application/CV and making a good impression - survey respondents were asked to rate their confidence using a 5-point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘a great deal’

For each of the sub-scales, responses are coded from 1 (low self-efficacy) to 5 (high self-efficacy). Using the mean from the responses from the nine items, a continuous job search self-efficacy scale was created from 1 to 5. Those scoring between 1 and 3.78 are coded as ‘lower job search self-efficacy’ (around 50% of the control group at baseline, as the control group provides a representative picture of the eligible population), with a higher score coded as ‘higher job search self-efficacy’. The impact of Group Work was measured by comparing both the mean scores and the proportions scoring as having ‘higher job search self-efficacy’ of the Group Work and control groups.

- confidence in finding a job was measured with the question:

Which of the following statements best describes your confidence in getting a job within 13 weeks?

- certain that I will find a job

- likely that I will find a job

- likely that I won’t find a job

- certain that I won’t find a job

Confidence is measured as proportion who described their confidence as ‘certain’ or ‘likely that I will find a job’.

- someone’s perceived ability to influence their propensity to find work was measured with the question:

In your opinion, which of the following plays the greatest role in securing a job placement?

- luck

- who you know

- your educational background

- your previous work experience

- the number of jobs you apply for

- effort put into each application