Managing incidents of ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in England

Published 21 November 2022

Applies to England

Foreword

This guidance for managing incidents of ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in England has been developed by the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP) team at the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). UKHSA is an executive agency sponsored by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC).

The purpose is to provide public health guidance to clinicians, microbiologists, epidemiologists and public health authorities concerning the management of ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. This includes a summary of the epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in N. gonorrhoeae in England in the period following the publication of the 2013 GRASP Action Plan and provides guidance for responding to an incident of ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Background

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), the causative agent of gonorrhoea, has developed resistance to all classes of antibiotics recommended for treatment including third-generation cephalosporins, the last-line option for monotherapy (1). If untreated, gonorrhoea can lead to complications including pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Intramuscular (IM) ceftriaxone is recommended as the first-line therapeutic for managing gonorrhoea in England (2).

Since the publication of the GRASP Action Plan in 2013 (3), there have been marked increases in gonorrhoea diagnoses in England. Between 2013 to 2021 reported diagnoses of gonorrhoea have risen by 64% in England, from 31,114 to 51,074 (4). Consequently, gonorrhoea is now the second most-commonly diagnosed sexually transmitted infection (STI) in England. Additionally:

- following an outbreak of high-level azithromycin resistant (HL-AziR) NG in young heterosexuals in Leeds in 2014 and 2015, there is now sustained transmission of HL-AziR NG in both heterosexual and gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) networks in England (5)

- the first global treatment failure for gonorrhoea with a dual-therapy regimen, due to an extensively drug-resistant (XDR) NG strain, acquired in Japan, was verified in the UK in 2016 (6)

- the World Health Organization (WHO) designated antibiotic resistant NG as a high-priority pathogen in 2017 (7)

- the world’s first XDR-NG strain with ceftriaxone resistance and HL-AziR, acquired in Thailand, was reported in the UK in 2018 (8, 9)

- in 2019, 1 g ceftriaxone monotherapy became the first-line national recommended treatment for gonorrhoea (2)

- further isolates with ceftriaxone resistance were also reported in England; 2 in 2018 (10), 3 in 2019 (11), 2 in 2021 and 9 in 2022 (1)

The emergence and, in some instances, persistence of highly resistant NG strains in recent years is of worldwide concern. The FC428 clone associated with ceftriaxone resistance detected in the UK in 2018 (9, 10) was first identified in Japan in 2015 (12) and later isolated in Australia (13), Canada (14), Denmark (15), France (16) in 2017, and Ireland (17) in 2018.

While sustained local transmission of the FC428 clone in the UK has not been reported to date, the ease with which this highly resistant strain spread internationally attests to how rapidly gonorrhoea might become untreatable. Guidance is therefore warranted which describes the process of managing and responding to the emergence of NG strains with resistance to first-line therapeutics in England.

Multi-drug resistant (MDR) gonorrhoea definition (18 )

Resistant to one of the category I antibiotics (which includes injectable extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESC), oral ESCs extended-spectrum cephalosporins and azithromycin) and at least 2 of the antibiotic classes listed in category II (which includes penicillins, fluoroquinolones, spectinomycin, aminoglycosides and carbapenems).

Extremely-drug resistant (XDR) gonorrhoea definition (18 )

Resistant to 2 or more of the antibiotic classes in category I and 3 or more in category II.

Objectives of 2013 Action Plan

In 2013, the Health Protection Agency (HPA, which became Public Health England in 2013 and UKHSA in 2021) established 6 objectives as part of the GRASP Action Plan to advise on a national response to gonococcal antimicrobial resistance (AMR) (3). These were to:

- provide robust and timely surveillance data on AMR gonorrhoea in England and Wales

- advise on appropriate changes to the national guidelines for the management of gonorrhoea

- give technical advice to clinical microbiologists on appropriate methods for detection of decreased susceptibility or resistant gonococcal isolates in the laboratory

- provide support to allow rapid detection of treatment failures

- communicate to relevant healthcare professionals and at-risk groups to raise awareness of the threat of untreatable gonorrhoea

- promote prevention messages to enhance public health control of gonorrhoea

Improvements to surveillance since 2013

A paper describing trends in gonococcal AMR, improvements to surveillance and the experience of implementing the Action Plan’s recommendations to respond to incidents of resistant N. gonorrhoeae in England has recently been published (19).

Sentinel surveillance data

Since 2000, UKHSA has monitored trends in gonococcal AMR in England and Wales and has provided robust data through GRASP to inform the revision of national clinical management guidelines, most recently in 2019 (1, 2). A detailed description of the GRASP methodology has been published previously (20). The protocol describes the objectives of the programme, the roles of participating sentinel sexual health services (SHSs) and their corresponding laboratories, and the antimicrobial susceptibility testing carried out by the UKHSA antimicrobial resistant STIs (AMRSTI) national reference laboratory.

Consecutive annual GRASP reports have presented clear evidence of increasing azithromycin resistance (minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) >0.5 mg/L, EUCAST breakpoint 2018) from 4.7% in 2016 to 15.2% in 2021 (1). Cefixime resistance has been shown to remain low, at 0.3% in 2021. However, ciprofloxacin (46.9% in 2021) and, most notably, tetracycline (75.2% in 2021) resistance have continued to increase despite infrequent use for treatment of gonorrhoea. In recent years, ceftriaxone susceptibility has improved, with a declining proportion of isolates demonstrating reduced ceftriaxone susceptibility (MIC >0.03 mg/L), from 2018 (7.1%) to 2021 (0.07%).

Penicillin resistance has remained at elevated levels above the 5% WHO threshold since 2002 (14.1% in 2021), with consistently increasing prevalence of plasmid-mediated high-level resistance. Conversely, patterns in spectinomycin resistance have remained consistent since the establishment of the surveillance programme in 2000, with no spectinomycin resistant cases identified in recent years. In 2019, gentamicin susceptibility testing was added to assess the suitability of this antibiotic as an alternative treatment for gonorrhoea (1). With a low modal MIC (4 mg/L), GRASP data has provided in vitro evidence to support the use of gentamicin for treating gonorrhoea.

Responding to incidents and treatment failures

As well as publishing data on gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibility (20) and informing revisions to national management guidelines (2), UKHSA has co-ordinated responses to an outbreak of high-level azithromycin (HL-AziR) NG in Leeds in 2015 (5, 21) and cases of ceftriaxone resistant NG in England in 2016 (6), 2018 (9, 10), 2019 (10) and 2022 (1). Information and lessons learned from these incidents were disseminated as peer-reviewed publications, presented at local, national and international conferences and shared in collaborations with universities and research consortiums to contribute to the global effort to stop the spread of resistant gonorrhoea.

Close collaboration between SHSs, local laboratories and UKHSA colleagues have been essential in identifying the common factor across all cases of ceftriaxone resistance reported in the UK since 2013: travel abroad, mostly to the Asia-Pacific region. This intelligence was fed into the updated 2019 national guideline for managing infection with NG to recommend multi-site testing for those who may have acquired gonorrhoea in the Asia-Pacific region and to stress the importance of test-of-cure for returning travellers with gonorrhoea (2).

Introducing real-time surveillance

In 2011, UKHSA launched an online tool for clinicians to report suspected cases of gonorrhoea treatment failure to first-line treatment. Since 2014, sentinel surveillance data in GRASP has been supplemented by UKHSA’s Second-Generation Surveillance System (SGSS), which captures real-time data on infectious diseases and AMR from primary diagnostic laboratories (22). National guidelines recommend that all NG isolates are tested for ceftriaxone susceptibility and referred to the national reference laboratory if suspected to be resistant (MIC >0.125 mg/L, EUCAST breakpoint). Following the detection of the first XDR NG case in 2018 (8), UKHSA sought to improve real-time detection of ceftriaxone resistant NG. UKHSA reviews SGSS data from primary diagnostic laboratories on a weekly basis and contacts laboratories that have reported a ceftriaxone-resistant NG isolate to verify that it has been sent to the national reference laboratory for confirmation. Any isolates that are confirmed as ceftriaxone resistant initiate a rapid risk assessment.

Between January 2021 and June 2022, 520 isolates (1.9% of all NG isolates) were recorded in SGSS that were not tested for ceftriaxone susceptibility. A further 53 were reported as ceftriaxone resistant but had not been received by the national reference laboratory. Follow-up of these isolates found that 34 out of 53 (64%) isolates were either misclassified as resistant by the testing laboratory (mainly due to transcription errors), were quality control isolates, or were confirmed sensitive by the national reference laboratory once the testing laboratory was prompted to send in isolates for confirmation. Only 2 out of 53 (3.8%) were confirmed resistant. The remaining 17 isolates were not available for confirmatory antimicrobial susceptibility testing. However as reporting of STIs by laboratories to SGSS operates on a voluntary basis, not all isolates with suspected resistance are reported. Indeed, 9 other isolates were received by the national reference laboratory and confirmed to be resistant during this period, although the isolates were not recorded in SGSS. This has demonstrated that awareness of the national guidelines requires strengthening among primary diagnostic laboratories.

Managing Incidents

The purpose of this document is to provide public health guidance to clinicians, microbiologists, epidemiologists and public health authorities in responding to cases of ceftriaxone-resistant NG in England.

Defining the risk

The emergence of NG strains with ceftriaxone resistance would significantly compromise our ability to successfully treat gonorrhoea given the paucity of alternative treatments. Hence, the detection of one or more cases of ceftriaxone-resistant NG, as confirmed by the national reference laboratory, is an event of concern. Similarly, confirmed gonorrhoea treatment failures with ceftriaxone may be indicative of an outbreak of a resistant strain or strains and, like reports of ceftriaxone-resistant NG, should be risk assessed.

The case definitions for gonorrhoea treatment failures described below are adapted from the working definitions recommended by the 2019 ECDC Response Plan to control drug resistant gonorrhoea in Europe (23).

Probable case: Points 1 to 3.

Confirmed case: Points 1 to 4.

1. A patient who returns for test of cure or who has persistent symptoms after having received treatment for laboratory-confirmed gonorrhoea with the recommended therapeutic regimen (ceftriaxone 1 g monotherapy).

and

2. Remains positive for one of the following tests for N. gonorrhoeae:

• isolation of N. gonorrhoeae by culture taken at least 72 hours after completion of treatment*

or

• positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) taken 2 to 3 weeks after completion of treatment**

and

3. Reinfection is excluded as far as feasible.

4. Resistance to ceftriaxone (MIC >0.125 mg/L) as confirmed by the national reference laboratory.

*In case of possible treatment failure, no gonococcal isolate is available pre- and/or post-treatment (only diagnosed using NAATs) or the cultured isolate does not show phenotypic resistance to the antimicrobials used for treatment (failures to treat particularly pharyngeal gonorrhoea have been recorded with isolates that are phenotypically susceptible to the antimicrobials used for treatment).

**Culture-negative and NAAT-positive specimens 2 weeks after treatment can be due to persistent nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) and in these cases, a repeated NAAT one week later should be considered.

Reporting an incident

The identification of a possible incident of ceftriaxone-resistant gonorrhoea in the UK may be raised by any number of public health stakeholders, including sexual health clinicians or health advisors, general practitioners (GPs), microbiologists, health protection teams (HPTs), Field Services (FS), sexual health facilitators (SHFs), Directors of Public Health (DsPH) or the national teams for Blood Safety, Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and HIV (BSHSH) and Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (AMRHAI) in UKHSA.

Suspected cases of ceftriaxone-resistant NG should be reported to UKHSA via email notification to [email protected]. The national guidelines for managing infection with NG recommend that all NG isolates are tested for ceftriaxone susceptibility by primary diagnostic laboratories (2). NG isolates with suspected ceftriaxone resistance (MIC >0.125 mg/L, EUCAST breakpoint), as determined using a gradient strip method, should be immediately referred to the national reference laboratory at UKHSA Colindale for confirmation (24).

Cases of probable or confirmed treatment failure with ceftriaxone monotherapy should be reported to UKHSA via the online treatment failure reporting tool. If an NG isolate(s) is available for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, the primary diagnostic laboratory should send it immediately to the national reference laboratory (if not done so already), even if found to be ceftriaxone susceptible at the primary lab. Only authorised users at SHSs have access to the secure online treatment failure reporting tool. If access is required, this can be requested by emailing [email protected]. Reports of ceftriaxone treatment failures will be followed up by a consultant microbiologist at UKHSA, who will contact the reporter to ascertain further information for a risk assessment.

Risk assessment

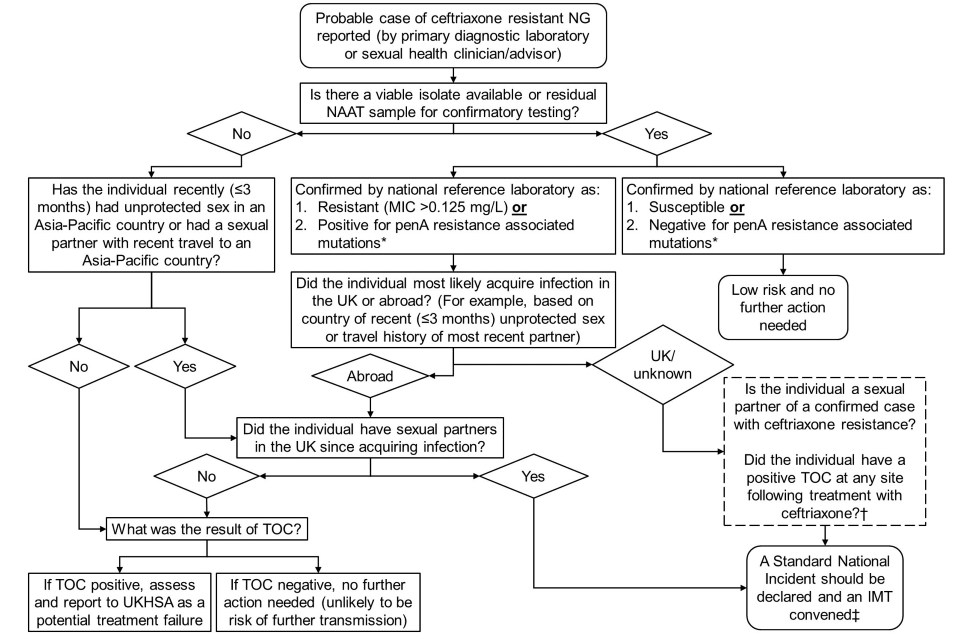

The UKHSA STI national team is responsible for co-ordinating a risk assessment of the threat to public health. Figure 1 below can be used to guide the risk assessment.

A Standard National Incident is convened for incidents that require coordination and resources beyond normal operation capacity and brings together expertise including national, regional and local sexual health teams, microbiologists, public health commissioners, and other external bodies as required. However, the declaration of a Standard National Incident is not required where there is no reasonable evidence of potential or actual further spread within the UK. For example, cases among individuals who acquired their infection abroad, have no sexual partners in the UK and who respond to treatment are unlikely to be a risk for further transmission. However, as AMR in NG is an international public health threat, the National Focal Point (NFP) and local authorities for countries associated with cases should be alerted as soon as the location of sexual contact is disclosed.

Under International Health Regulations Article 4 (25), NFPs are responsible for notifying the WHO of relevant health events on behalf of the State Party. Other international stakeholders may be informally notified via the ECDC’s EpiPulse platform for STIs. If the incident constitutes a public health risk to a EU Member State country, the European Commission can be informed (with DHSC approval) who will post on the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) on behalf of UKHSA. The UK IHR NFP can be contacted for advice on both IHR and EWRS notifications at [email protected]

An unconfirmed case of ceftriaxone-resistant NG that is reported by a primary diagnostic laboratory but cannot be verified due to the unavailability of an isolate for confirmatory antimicrobial susceptibility testing, should also be considered for a risk assessment while bearing in mind that most isolates with suspected resistance are misclassified or found to be susceptible. However, if a residual NAAT specimen is available then this should be sent to the national reference laboratory for molecular detection of ceftriaxone resistance. A real-time PCR assay is available at UKHSA’s national reference laboratory which detects the most commonly occurring mutations within the NG penA gene, responsible for causing ceftriaxone resistance (that is those associated within international clones FC428, A8806 and GU140106 specifically). For further details regarding the assay please contact the reference laboratory directly.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for risk assessment of ceftriaxone resistant NG cases

An accessible text version of this flow diagram is also available.

*Detected by PCR targeting 2 out of 5 mutations associated with resistance within penA which are both found in alleles 60 (found in FC428 clone), 64 (found in A8806 clone) and 59 (found in GU140106 clone).

†These questions should ideally be asked prior to the first IMT; however the IMT should be convened regardless of the outcome to these questions.

‡The IMT will be convened by the UKHSA STI team.

Incident response co-ordination

The aim of an IMT has previously been described in guidance published by UKHSA on managing outbreaks of STIs (although instead referred to as an Outbreak Control Team (OCT)) (26). Briefly, they aim to:

- determine whether an outbreak or incident has occurred or is occurring

- establish and confirm the correct diagnosis and nature of the challenge

- determine the immediate steps needed to identify further cases and contacts

- plan and implement control measures to bring the outbreak under control

In the context of ceftriaxone-resistant gonorrhoea, an IMT should be convened at the earliest opportunity by the national UKHSA STI team and chaired by a consultant microbiologist or epidemiologist. Clinical, microbiological and health protection experts at local, regional and national levels are invited to support the investigation and management of cases. The UKHSA communications team and, if appropriate, third sector organisations may also be involved in the incident response.

Investigation

Refining the case definition

The working case definitions described above should be used by the IMT in the preliminary investigation. However, as the investigation progresses, these should be refined based on the demographic characteristics of cases and their geographical distribution. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) information may also be used to inform case definitions.

Microbiological investigation

The national guidelines for managing infection with NG recommend pharyngeal testing in those with suspected or confirmed ceftriaxone resistance or those with recent travel from the Asia-Pacific region (2). Pharyngeal infection is more difficult to treat and treatment failures have occurred most often at this anatomical site (6, 9). The national reference laboratory may therefore request additional samples to be taken by the SHS. WGS of NG isolates and the penA PCR of isolates and clinical specimens will be performed by the national reference laboratory.

Epidemiological investigation

The national guidance for consultations requires the taking of an individual’s sexual history and lists specific questions which should be asked, the setting in which consultations should take place and instructions for maintaining patient confidentiality (27). In addition to those asked in the initial risk assessment, it is particularly important to include a travel history.

Locally-focused questionnaires may draw upon supplementary outbreak investigation questions provided by UKHSA, available through the Field Service (FS) Portal for FS teams and Health Protection Teams (HPTs). Information obtained from sexual history consultations or local questionnaires should be used by the IMT to create a brief Situation Report (SitRep) which summarises the demographics (age, sex, ethnicity) of cases and their spatiotemporal distribution. SitReps should be regularly updated through the outbreak. Data from national surveillance systems, such as the GUMCAD STI surveillance system and SGSS, may also be used to assess local, regional and national trends. If available, WGS data may be used to construct a phylogenetic tree to establish the likely resistance mechanisms and the genetic relatedness of new and previously reported cases.

Communication

The Chief Medical Advisor (CMA) and Chief Scientific Officer (CSO) at UKHSA should be informed prior to the formation of an IMT. Following the establishment of an IMT, a briefing note should be promptly cascaded internally, to regional teams and microbiology networks to inform them of the ongoing investigation. A CMO briefing should also be prepared and sent out via the CMA of UKHSA’s office to be shared with the Chief Executive and DHSC.

International partners (the WHO and ECDC) should be notified separately, as well as, where the strain was likely to have been acquired outside the UK, the NFP for countries linked to a case(s), or their sexual partner(s). An email notification should be disseminated to members of the BASHH clinical network to inform them of the detection of ceftriaxone-resistant NG in England and, if appropriate, to advise on further action. A publicly available resistance alert or high-level case summary with non-confidential contents may also be published on GOV.UK, with previous examples such as, ‘Antibiotic-resistant strain of gonorrhoea detected in London’ and ‘More cases of antibiotic resistant gonorrhoea identified in England’. Rapid communications to academic journals should also be considered. As the outbreak progresses, further briefings, alerts or case details should be communicated where major developments, such as the detection of a new case(s), arise.

Previous incidents of resistant NG strains have drawn widespread media attention. As such, the IMT should work alongside the UKHSA communications team to prepare a reactive statement for potential press enquiries and frequently asked questions (FAQs) to support national and local teams.

Control measures

The control measures described below should be introduced immediately after the identification of the first case to minimise sequelae and prevent onward transmission of resistant strains.

Clinical management

Effective management of resistant gonorrhoea can limit spread by decreasing the time an individual is infectious for, thereby minimising the exposure time to a sexual partner(s). Clinicians should follow the national guidance for managing infection with NG (2). The majority of patients with ceftriaxone-resistant NG infection of the genital tract will still clear infection with ceftriaxone 1g IM, but treatment failures occur more frequently for pharyngeal infection.

The Consultant Microbiologist at UKHSA will provide treatment advice for these cases. Alternative treatment options are limited, and where possible should be guided by the results of antibiotic susceptibility testing. Isolates with ceftriaxone resistance are usually also resistant to most other antimicrobials. Often these multi-drug isolates remain susceptible to spectinomycin and have low gentamicin MICs, however both of these antimicrobials have a high failure rate in treating pharyngeal infections, and spectinomycin is also no longer available in the UK. If the isolate is susceptible to azithromycin, treatment with azithromycin 2g orally plus gentamicin 240 mg IM may be given. Generally, ertapenem has similar MICs to ceftriaxone, but for some isolates with raised ceftriaxone MICs, the ertapenem MIC is lower. This has allowed some infections with XDR N. gonorrhoeae to be successfully treated with ertapenem when ceftriaxone has failed (9,10). Three days of IV ertapenem 1 g was used for these cases, although this was a pragmatic choice and not guided by clinical trial data.

All cases should be advised to return for a test-of-cure to ensure the infection has cleared. Particular attention should be paid to checking for microbiological cure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea owing to the difficulty in clearing infection at this site. Repeat reminders should be issued to cases who fail to return for a test-of-cure.

Partner notification (PN)

PN is essential for containing spread of ceftriaxone-resistant NG. The sexual partner(s) of cases should be notified as soon as possible. The national guidance states that (2):

- for those presenting after 14 days of exposure, treatment is only recommended following a positive test for gonorrhoea

- for those presenting within 14 days of exposure, epidemiological treatment should be considered based on a clinical risk assessment and following a discussion with the patient. In asymptomatic individuals, it may be appropriate to not give epidemiological treatment, and to repeat testing 2 weeks after exposure

Extensive efforts should be made by health advisors at SHSs to follow-up contactable and unresponsive partners, including through repeated call or text reminders to attend a SHS, liaison with other local service providers to ascertain whether a partner has attended their service for STI testing and/or treatment following PN, and even home or frequently-attended venue visits if possible. Partners outside of the UK may be contacted by the relevant local authorities through liaison with NFPs.

Health promotion

Attendances to SHSs present opportunities for reminding individuals of safer sex practices, such as the use of condoms and STI testing upon partner change, to promote sexual health and wellbeing. Given that previous treatment failures have been associated with travel abroad, mostly to the Asia-Pacific region (6, 9), the provision of sexual health advice should also be considered for individuals attending travel health services, more information on STI prevention for travellers and travel health professionals is provided on the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC) website. Health promotion activities to non-travellers should include the provision of sexual health information and STI prevention advice, as well as signposting to SHSs, including online STI self-sampling services, and condom distribution schemes – this information and these messages can be disseminated through a combination of mainstream media (press or radio) or social media.

Declaring the end of the incident

Review the risk assessment

The IMT should regularly review the questions posed by the initial risk assessment to determine whether a continued incident response is warranted. The IMT can be stood down if:

- all known cases and, if applicable, sexual partner or partners have been treated successfully

- there is no further evidence of onwards transmission within the UK

The second point may be difficult to ascertain if there are uncontactable sexual partners in the UK. This includes partners for whom the index case cannot or chooses not to identify, those who do not or cannot respond to contact by health advisors, or for whom contact details are unknown or erroneous. While there are no agreed criteria about an acceptable level of risk, the public health threat posed by uncontactable sexual partners should be reviewed in light of any available sexual history information, including their prolificity and partnership type; type of sexual contact and sites of exposure; and condom or barrier use with a known case or cases. If there is evidence that uncontactable sexual partners might be harbouring a reservoir of resistant infection in the UK, the incident response should continue and health promotion activities, such as signposting to clinical services in venues known to be frequented by the case or cases and sexual partners, should be increased.

Report writing

A report should be prepared by the IMT at the conclusion of the incident response and circulated with relevant stakeholders. The report should be structured as described in Appendix 11 of the UKHSA communicable disease outbreak management guidelines and must include lessons learned to inform future incident responses (28). It should be stored centrally on the Field Services Portal. Ideally, key findings should be published in peer-reviewed articles for wider readership and learning opportunities.

Figure 1 flow diagram text description

A risk assessment should be carried out when there is a probable case of ceftriaxone resistant NG reported (by primary diagnostic laboratory, sexual health clinician or advisor).

Question 1: Is there a viable isolate available or residual NAAT sample for confirmatory testing?

If no, then go to Question 5.

If yes, the isolate or NAAT sample should be referred to the UKHSA AMRSTI national reference laboratory for confirmatory testing. Proceed to either Outcome 1 or Outcome 2.

Outcome 1: Confirmed by national reference laboratory as 1) resistant (MIC >0.125 mg/L) or 2) PCR positive (for penA resistance associated mutations)*

If Outcome 1, then go to Question 2.

Outcome 2: Confirmed by national reference laboratory as 1) susceptible or 2) PCR negative (for penA resistance associated mutations)*

If Outcome 2, then there is low risk and no further action is needed.

Question 2: Did the individual most likely acquire infection in the UK or abroad? (for example, country of recent (≤ 3 months) unprotected sex or travel history of most recent partner)?

If ‘Abroad’, then go to Question 3.

If ‘UK’ or ‘unknown’, then a Standard National Incident should be declared and an IMT convened‡. The following questions should be asked ideally before the IMT:

- is the individual a sexual partner of a confirmed case with ceftriaxone resistance?

- did the individual have a positive TOC at any site following treatment with ceftriaxone?†

Question 3: Did the individual have sexual partners in the UK since acquiring infection?

If no, then go to Question 4.

If yes, then a Standard National Incident should be declared and an IMT convened‡.

Question 4: What was the result of TOC?

If TOC positive, assess and report to UKHSA as a potential treatment failure.

If TOC negative, no further action needed (unlikely to be risk of further transmission).

Question 5: Has the individual recently (≤3 months) had unprotected sex in an Asia-Pacific country or had a sexual partner with recent travel to an Asia-Pacific country?

If no, then go to Question 4.

If yes, then go to Question 3.

*Detected by PCR targeting 2 out of 5 mutations associated with resistance within penA which are both found in alleles 60 (found in FC428 clone), 64 (found in A8806 clone) and 59 (found in GU140106 clone).

†These questions should ideally be asked prior to the first IMT; however the IMT should be convened regardless of the outcome to these questions.

‡The IMT will be convened by the UKHSA STI team.

References

2. Fifer H, Saunders J, Suneeta S, Sadiq T, Fitzgerald M. ‘2018 UK national guideline for the management of infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae’. 2019 (accessed 23 August 2021)

3. Health Protection Agency (HPA). ‘Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP) Action Plan for England and Wales: Informing the Public Health Response’. 2013 (accessed 1 September 2021)

4. Public Health England (PHE). ‘Sexually transmitted infections and chlamydia screening in England: 2020’. 2021 (accessed 15 September 2021)

5. PHE. ‘Resistance Alert: High-level azithromycin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae’. 2015 (accessed 13 August 2021)

6. Fifer H, Natarajan U, Jones L, Alexander S, Hughes G, Golparian D and others. ‘Failure of Dual Antimicrobial Therapy in Treatment of Gonorrhea’. The New England Journal Medicine. 2016; volume 374: pages 2504 to 2506

7. World Health Organization (WHO). ‘WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed’. 2017 (accessed 1 September 2021)

8. PHE. ‘UK case of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with high-level resistance to azithromycin and resistance to ceftriaxone acquired abroad’. 2018 (accessed 5 August 2021)

9. Eyre D, Sanderson N, Lord E, Regisford-Reimmer N, Chau K, Barker L and others. ‘Gonorrhoea treatment failure caused by a Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with combined ceftriaxone and high-level azithromycin resistance, England, February 2018’. Eurosurveillance. 2018; volume 23 issue 27: article 1800323

10. Eyre D, Town K, Street T, Barker L, Sanderson N, Cole M and others. ‘Detection in the United Kingdom of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae FC428 clone, with ceftriaxone resistance and intermediate resistance to azithromycin, October to December 2018’. Eurosurveillance. 2019; volume 24 issue 10: article 1900147

11. PHE. ‘Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in England and Wales: Key findings from the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP 2019)’. 2020 (accessed 31 October 2022)

12. Nakayama S, Shimuta K, Furubayashi K, Kawahata T, Unemo M, Ohnishi M. ‘New ceftriaxone- and multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with a novel mosaic penA gene isolated in Japan’. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016; volume 60 issue 7: pages 4339 to 4341

13. Lahra MM, Martin I, Demczuk W, Jennison AV, Lee KI, Nakayama SI and others. ‘Cooperative Recognition of Internationally Disseminated Ceftriaxone-Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae Strain’. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2018; volume 24 issue 4

14. Lefebvre B, Martin I, Demczuk W, Deshaies L, Michaud S, Labbé AC and others. ‘Ceftriaxone-Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Canada, 2017’. Emerging Infectious Diseases . 2018; volume 24 issue 2: pages 381 to 383

15. Terkelsen D, Tolstrup J, Johnsen CH, Lund O, Larsen HK, Worning P and others. ‘Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection with ceftriaxone resistance and intermediate resistance to azithromycin, Denmark, 2017’. Eurosurveillance. 2017; volume 22 issue 42: article 1273

16. Poncin T, Fouere S, Braille A, Camelena F, Agsous M, Bebear C and others. ‘Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae failing treatment with ceftriaxone and doxycycline in France, November 2017’. Eurosurveillance. 2018; volume 23 issue 21: article e1002344

17. Golparian D, Rose L, Lynam A, Mohamed A, Bercot B, Ohnishi M and others. ‘Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolate, belonging to the internationally spreading Japanese FC428 clone, with ceftriaxone resistance and intermediate resistance to azithromycin, Ireland, August 2018’. Eurosurveillance. 2018; volume 23 issue 47: article 4339

18. Tapsall JW, Ndowa F, Lewis DA, Unemo M. ‘Meeting the public health challenge of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae’. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2009 September; volume 7 issue 7: pages 821 to 834

19. Merrick R, Cole M, Pitt R, Enayat Q, Ivanov Z, Day M and others. ‘Antimicrobial-resistant gonorrhoea: the national public health response, England, 2013 to 2020’. Eurosurveillance. 2022; volume 27 issue 40: article 2200057

20. PHE. ‘GRASP protocol’. 2020 (accessed 1 September 2021)

21. Smolarchuk C, Wensley A, Padfield S, Fifer H, Lee A, Hughes G. ‘Persistence of an outbreak of gonorrhoea with high-level resistance to azithromycin in England, November 2014-May 2018’. Eurosurveillance. 2018; volume 23 issue 23: article 1800287

22. PHE. ‘Laboratory reporting to Public Health England: A guide for diagnostic laboratories. 2020’ (accessed: 23 August 2021)

23. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. ‘Response plan to control and manage the threat of multi- and extensively drug-resistant gonorrhoea in Europe’. 2019 (accessed 1 September 2021)

24. UKHSA. ‘Bacteriology Reference Department user manual’. 2022 (accessed 19 October 2022)

25. WHO. ‘International Health Regulations (2005) Third Edition’. 2016 (accessed 1 September 2021)

26. PHE. ‘Managing outbreaks of Sexually Transmitted Infections: Operational guidance’. 2017 (accessed 24 August 2021)

27. Brook G, Church H, Evans C, Jenkison N, McClean H, Mohammed H, Munro H and others. ‘2019 UK National guideline for consultations requiring sexual history taking: Clinical Effectiveness Group British Association for Sexual Health and HIV’. 2020 (accessed 27 August 2021)

28. PHE. ‘Communicable Disease Outbreak Management: Operational guidance’. 2014 (accessed 1 September 2021)