Contingency planning for marine pollution preparedness and response: guidelines for ports

Updated 16 August 2024

1. List of abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|

| BPA | British Ports Association |

| CPSO | Counter Pollution and Salvage Officer |

| DARD | Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (NI) |

| DEFRA | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| EA | Environment Agency |

| EG | Environment Group |

| GT | Gross Tonnage |

| ISAA | The International Spill Accreditation Association |

| JRCC | Joint Rescue Coordination Centre |

| MCA | Maritime and Coastguard Agency |

| MMO | Marine Management Organisation |

| MRC | Marine Response Centre |

| MRCC | Maritime Rescue Coordination Centres |

| MS-ML | Marine Scotland – Marine Laboratory |

| NCP | National Contingency Plan for Marine Pollution from Shipping & Offshore Installations |

| NE | Natural England |

| NIEA | Northern Ireland Environment Agency |

| NRW | Natural Resources Wales |

| OMT | Oil Spill Management Team |

| OPRC Convention | Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation Convention |

| OSRO | Oil Spill Response Organisation |

| POLREP | Pollution Report |

| SAC | Special Area of Conservation |

| SCU | Salvage Control Unit |

| SEPA | Scottish Environment Protection Agency |

| SI | Statutory Instrument |

| SITREP | Situation Report |

| SOSREP | Secretary of State’s Representative for Maritime Salvage and Intervention |

| SSSI | Site of Special Scientific Interest |

| STOp | Scientific, Technical and Operational Guidance Notes |

| UKHMA | UK Harbour Masters Association |

| UKMPG | UK Major Ports Group |

| UNCLOS | United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 |

2. Scope and purpose

2.1 Introduction

2.1.1 Harbour authority responsibility

Harbour authorities have overall responsibility for the safety of marine operations on waters within their jurisdiction. Their underlying obligation is to manage the harbour so that it can be used in a safe and efficient manner. They must also ensure that the environment is safeguarded. These duties are also a commercial imperative. A serious accident is likely not only to cause serious disruption to the port at the time, but may well have longer term impacts. Cleaning up pollution is an inherently difficult and time consuming process. It may be longer still before the port returns to full running order, and recovers from the cost and possible lost business caused by a large spill. It is therefore much better to work for accident prevention rather than having to deal with the consequences.

2.1.2 Purpose of the plan

The purpose of a port’s contingency plan for marine pollution is to ensure that there is a timely, measured and effective response to incidents. A port that is prepared will be able to deal with an incident more quickly, so that normal port operations can be resumed sooner – with obvious benefits to port users and the harbour authority.

The marine pollution contingency plan is likely to be just one part of a port’s overall emergency planning – which will also cover commercial and other aspects beyond the scope of either the Guide to Good Practice or these Guidelines.

These Guidelines relate in the first instance to implementation of the OPRC Convention under which obligations are placed on harbour authorities and oil handling facilities in relation to the pollution from oil. Most of the material contained in these guidelines is therefore specific to oil pollution. Oil is the most significant pollutant associated with port marine operations and strategies for dealing with it have been well-advanced through experience. As discussed later, harbour authorities have a statutory duty to plan a response to such incidents. It is expected that this statutory duty will be extended to other pollutants in due course. A contingency plan that is effective for oil pollution will have much in common with plans required to combat other pollutants. The hazards, and techniques for cleaning-up, will vary, but command and control procedures will be very similar.

These Guidelines recommend a quantified and risk based approach to contingency planning. This is a transparent process which lends itself to rational decision making. Benefits accrue both to those who draw-up the plans and to those who approve them. It is a sophisticated method but all harbour authorities have to ask themselves the question: ‘What is it worth planning for?’ and a quantified analysis will help provide the answer.

2.1.3 Legal basis for marine pollution contingency planning

As a party to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the UK has an obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment.

Section 293 of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995, as amended by the Merchant Shipping and Maritime Security Act 1997, gives the Secretary of State for Transport the function of taking, or co-ordinating, measures to reduce and minimise the effects of marine pollution. The Environment Act 1995 places similar duties on the Environment Agency for England and Wales with respect to pollution from land-based sources.

The UK Government also has obligations under the International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation 1990 (the OPRC Convention). The Merchant Shipping (Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation Convention) Regulations 1998 (SI 1998 No 1056) implement the obligations of the Convention. In particular, they require harbour authorities to have a duty to prepare plans to clear oil spills from their harbour and for those plans to be compatible with the National Contingency Plan (NCP) a strategic overview for responses to marine pollution from shipping and offshore installations.

The purpose of the NCP is to ensure that there is a timely, measured and effective response to incidents of, and impact from, marine pollution from shipping and offshore installations. It sets out the circumstances in which the Maritime and Coastguard Agency deploys the UK’s national assets to respond to a marine pollution incident to protect the overriding public interest. It is essential reading for anyone preparing a marine pollution contingency plan for a port. These Guidelines assume that the reader is familiar with the NCP. The plans prepared by harbour authorities, oil handling facilities, coastal local authorities and offshore installations underlie this national plan and provide detailed information on the local response to marine incidents. They should also describe arrangements for mutual support and need to be fully compatible with plans that operate at national levels.

2.2. Other legislation relevant to these Guidelines

2.2.1 The Port Marine Safety Code

The Port Marine Safety Code which harbour authorities have adopted and agreed to implement, proposes that all the functions of a harbour authority in relation to marine operations should be regulated through a safety management system, based on a formal risk assessment of the hazards facing their port and appropriate measures to prevent them. The Code aims to improve safety for those who use or work in ports, their ships, passengers and cargoes, and the environment.

2.2.2 Guide to Good Practice on Port Marine Operations

A Guide to Good Practice on Port Marine Operations has been issued by the Department for Transport to assist authorities to develop such systems and to manage their marine operations thereby. The Guide to Good Practice does not deal in detail with planning a response to marine pollution – that is the function of these Guidelines. These Guidelines also support a National Contingency Plan, prepared and managed by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA).

2.2.3 Dangerous Substances in Harbour Areas Regulations SI 1987 No 37

Instructions for those who must comply with the Regulations which control the carriage, handling and storage of dangerous substances in harbours and harbour areas. See ‘A guide to Dangerous Substances in Harbour Areas Regulations 1987’

2.2.4 The Dangerous Vessels Act 1985

The Port Marine Safety Code recognises the potential need to give directions in relation to a dangerous vessel and states that this should be addressed in the port’s safety management system. Dangerous vessels are those which, because of their condition, or the nature or the condition of anything they contain, might involve a grave and imminent danger to the safety of persons or property. A harbour authority should hold contingency plans to deal with the threat posed by dangerous vessels when admitted to, or ordered to leave the port. These should also cover the threat of marine pollution from such vessels which may sink or founder in the harbour thereby preventing or seriously prejudicing the use of the harbour by other vessels.

2.2.5 The Civil Contingencies Act 2004

Local authorities, as Category 1 responders, in the United Kingdom have a responsibility under The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 to assess the risk of, plan, and exercise for emergencies. Local authorities have prepared, and implemented, local response plans based on these powers.

In Northern Ireland, the Water (Northern Ireland) Order 1999 gives the Department of the Environment powers to undertake pollution clean-up work through the Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) as it considers appropriate. NIEA prepares local response plans in the same way as local authorities do elsewhere in the United Kingdom.

“Marine pollution” in the National Contingency Plan refers to pollution by oil or other hazardous substances.

“Oil” means oil of any description and includes spirit produced from oil of any description, and also includes coal tar.

“Other hazardous substances” are those substances prescribed under section 138A of the The Merchant Shipping Act 1995. They also include any substance that, although not so prescribed, is liable to create hazards to human health, to harm living resources and marine life, to damage amenities or to interfere with other legitimate uses of the sea. Such pollution can result from spills of ships’ cargoes carried in bulk or in packages, ships’ bunkers and/or stores’, and leaks from oil and gas installations and pipelines.

2.3. Area covered

The Port Marine Safety Code calls for every harbour authority to have a safety management system for marine operations in its waters, developed after formal risk assessment. That safety management system should include plans to deal with emergencies arising in those waters. To ensure that the contingency plan for marine pollution dovetails with other plans developed by the harbour authority, they should cover the same area. The integrity of a harbour authority plan depends upon removing any doubt over who is responsible for what. The National Contingency Plan gives some guidance on the responsibilities that have been imposed or accepted for the clean up of pollution within the jurisdiction of a harbour authority as follows:

2.4. Responsibility for clean-up operations

| Location of pollution | Responsibility for ensuring clean up |

|---|---|

| On the water: jetties, wharves, structures, beach or shoreline owned by the harbour authority within the port/harbour area |

Harbour authority |

| Shoreline (including land exposed by falling tide) |

Local authority/Northern Ireland Environment Agency |

| Jetties, wharves, structures, beach or shoreline which is privately owned | Owner of the property / land |

| All other areas at sea (inside the EEZ/UK Pollution Control Zone and the UK Continental Shelf) |

MCA |

An agreement may need to be reached with the local authority on working together and to determine whether or not the harbour authority will deal only with the vertical faces of harbour structures. Agreement will also be required with the Agencies responsible for the regulation of waste in order to ensure that satisfactory arrangements are in place for the collection, storage, treatment and disposal of contaminated materials by the responsible party.

2.5 Consultation and approval

The MCA undertakes the approval of harbour authority and oil handling facility plans on behalf of the Secretary of State for the Department for Transport. Plans should be compiled in consultation with adjacent ports, local authorities, oil handling facilities, the Marine Management Organisation (MMO)), the Environment Agency, Natural England and their equivalents under the devolved administrations (see Section 5.2). Some of the agencies required to be consulted have to prepare response plans of their own. For consultation to be most effective they need to be given the harbour authority’s potential pollution assessment. These organisations should be able to assist greatly with the assessment of consequences of potential pollutants. It is therefore good practice to involve them from the outset in the port plan: it is not good practice to make a first approach with a completed draft.

Following consultation, the plan must then be submitted to the MCA for formal approval.

Harbour authorities must routinely review their plans every five years. They should also carry out a review following a significant incident, if there is a material change to the operations or infrastructure of the port or if a substantial amendment is required. If there is a material change to the plan, it is to be re-submitted to the statutory consultees and MCA for approval. Minor changes may be made through the normal amendment process. The consultation and approval process is described in Section 5.

3. Pre-cursors to contingency planning

3.1 Pollution - potential assessment

As a starting point, harbour authorities should draw upon the data collected as part of its formal risk assessment to assess the pollution potential of port marine operations in the port. In doing so they should have regard to the vessels which visit the port, the cargoes they carry, as well as any vessels which may respond to it in an emergency.

The following are some of the key points that should be considered when compiling a contingency plan.

3.1.1 Vessels

- Type, size and traffic density

- Collision/allision – potential and mitigation

- Availability of VTS

- Tug availability

- Pilotage

- Limiting environmental factors – winds, tides etc.

3.1.2 Cargoes

- Types and quantities – bulk, break bulk, containerised, specialised, project etc.

- Gas, liquid, solid – inherent dangers with each

- Cargo handling facilities – condition, appropriate for the vessel, trained operators etc.

- Likelihood of damaged cargo leading to hazardous situations – especially cross-contamination.

- Incorrect labelling, documentation

- Access to cargo manifests

- Any special measures required for occasional or project cargoes

3.1.3 Bunkering

- Bunkering facilities – fixed or mobile

- Shore tank storage facilities

- Types and quantities of bunker operations

- Management of bunkering procedures – notification, operation, checklists etc.

- Clear instructions in the event of a bunkering failure available to all.

- Availability of Tier 1 equipment at the bunkering position

3.2 The assessment of potential consequences

- The impact on port and associated operations and the ability to maintain normal business

- Potential health impacts on port workers and nearby residents

- Possible need to evacuate persons from the nearby area with the associated economic and logistical implications

- The impact on sensitive areas including agriculture, mariculture, fishing, wildlife and the environment in general.

- Risks to local economy and industry – water abstraction, tourism etc.

- The wider impact to be expected on the UK economy if trade is disrupted in the short and long term.

- The ability to comply with the requirement of the environmental regulator and statutory consultees.

- The ability to mount an extended clean-up campaign and the effect on staff welfare and capability

- The port or harbour’s reputation.

It must be remembered that repeated low impact events can have as great an impact as a large incident that occurs, say, only every five years.

3.3 Ability to respond

- Availability of own resources – equipment, personnel, numbers and capability

- Availability of nearby resources – other harbour, local authority or other.

- Availability of accredited marine pollution response contractor

- Ability to comply with the requirement of the environmental regulator and statutory consultees

3.4 Risk assessment

It is not possible for the OPRC regulations to cater for every eventuality that may be encountered in every port but a full and proper risk assessment will enable an effective response to be mounted in most cases in a controlled and efficient manner.

To ensure the best possible risk assessment a list of potential risks should be drawn up together with the potential consequence and likelihood of each. A risk matrix – similar to that shown below – may prove useful in determining the overall risk.

| Likelihood | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consequence | 1 rare | 2 unikely | 3 possible | 4 likely | 5 almost certain |

| 5 catastrophic | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

| 4 major | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 |

| 3 moderate | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| 2 minor | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| 1 negligible | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

3.5 Consultation with other bodies

For effective analysis, the results of the assessment need to be shared with others to realise the mutual benefits. This will normally be undertaken as part of the review process during the five yearly revalidation process. If there is a significant change to a port’s operation or infrastructure such to appreciably change the original risk assessment, the port must consider sharing this information with others so that they are aware and may amend their own plans as necessary.

The information is unlikely to be proprietary and should be made available to the following organisations and bodies:

-

MCA – who will be able to advise the extent to which the UK’s national assets will be deployed in mitigating the consequences of identified hazards. The MCA will also be keen to assess the port’s ability – and willingness – to contribute to regional and national assets for counter pollution operations. The Counter Pollution and Salvage Officers (CPSOs) of the MCA will be key points of contact.

-

Local authorities – who will be able to advise the extent to which its assets will be deployed as part of its own emergency plans. The local authority is likely to be keen to establish the limit of the port authority’s jurisdiction in its emergency plans.

-

Neighbouring ports – who will also share their own assessments with a view to establishing mutual support arrangements. By sharing the results of the uncertainty and sensitivity analyses, ports may be able to collaborate in the common ground of future data collection efforts and agree priorities.

-

The relevant Environmental Regulator - to ensure that all regulatory issues have been adequately assessed.

-

Other statutory consultees – who can advise on whether the consequences have been adequately assessed.

In analysing the results, it would be sensible to establish, in agreement with these bodies, levels of contamination and probability of events arising resulting in insignificant. These factors should then be combined to establish a threshold beyond which contingency planning for those groups of events has no utility for the port nor its immediate environs. These levels will also be useful as a basis for pollution incident reduction, forming part of the pollution prevention culture to be driven by the port management.

3.6 Catering for intolerable risks

Similarly, consideration should be given to identifying intolerable risks, should there be any, that are characterised by incidents usually having both a high frequency of occurrence and a high consequence. It is much better to manage such risks through preventative measures taken to ensure safe operations in a port rather than having to deploy a contingency plan to deal with an event that should not have been allowed to happen. The port’s safety management system and counter-pollution plan are therefore mutually dependent.

Contingency planning for events that have a very low probability of occurrence may be unjustified. The consequences would need to be extremely high to justify contingency planning for events that have a probability of occurring, say, only once every three hundred years or more. So, a port may choose to set transparent criteria and plan for contingencies that are only likely to happen more often than the pre-determined frequency criteria. Furthermore, a response is likely to be effective only when it has been exercised frequently in real or realistically simulated conditions. Further, equipment that is used infrequently is likely to be defective or out of date and the personnel ill-trained in its use. Ultimately, those paying dues to the port authority might successfully argue that it is unreasonable to charge for the exercise and up-keep of assets and skills which are not expected to be used.

In reaching such decisions a harbour authority will need to give careful consideration of the validity of any assessment that demonstrates the need or otherwise for the port to develop contingency plans. Within reasonable bounds, as the consequences become greater, the more important it is for the port to maintain a contingency plan to deal with that event, even though the probability of occurrence may be small.

Adjacent ports are encouraged to join forces and share contingency plans in circumstances where actions taken unilaterally cannot be justified. Thus, the costs of maintaining an effective response would be shared between those paying port dues.

3.7 Escalation of incidents

Harbour authorities must consider the need to address events which may escalate. The initiating events in a sequence may not have a probability of occurrence which is sufficiently frequent for a port acting reasonably to maintain contingency plans. However, such plans may escalate resulting in deployment of regional and/or national contingency plans. It is vital that contingency plans deal effectively with incidents that escalate, sometimes rapidly, in a planned and foreseeable way. Owing to the importance of this aspect of contingency planning, a considerable amount of advice on this point is offered to port authorities in these Guidelines.

3.8 Pollution risk assessment and the OPRC obligation

The obligation placed upon ports to make contingency plans under the OPRC Regulations is limited to incidents up to a certain size (See section 6) This may not reflect the findings of the pollution risk assessment. It may appear that the OPRC regulations require contingency plans for events that are predicted to occur only very rarely or fail to require contingency plans for events that are quite common.

The reason for the discrepancy arises because the OPRC Regulations were drawn-up as a broad brush measure that would find international acceptance. They represent the best that could be achieved using a pragmatic approach to suit all signatory States and all ports within those States.

A tiered approach may nevertheless be an appropriate method of determining the level of response. An example of this can be found in the OPRC Regulations for responding to oil pollution and is described in Section 6.2

4. Development of the port’s pollution plan

4.1 Introduction

Armed with the information from the risk assessment, including feedback from those with whom the risk assessment was shared and a framework for decision making on contingency planning, the harbour authority or oil handling facility should be able to develop its marine pollution contingency plan.

Any questions on the preparation or implementation of a plan should be referred to the MCA via the regional CPSO.

4.2 Document structure

A contingency plan should comprise four parts:

4.2.1 Preamble - An introduction to and record of the plan as well as providing aids to navigation and understanding of the plan.

4.2.2 Strategy section: this should describe the scope of the plan, including the geographical coverage, overview of the perceived risks, division of responsibilities, roles of authorities and the proposed response strategy. This section should be used for reference and for planning.

4.2.3 Action section: information detailing emergency procedures which allow for rapid mobilisation of resources such as notification flow charts and individual action cards.

4.2.4 Data section: this section should contain all relevant maps, lists and data sheets and support information required to assess an incident and conduct the response accordingly. Importantly, this section should contain the plan’s contact directory which must be clearly identified for immediate use.

For practical use, it may be beneficial to modify the order of these sections within the overall document. In any event, the plan list of contents must clearly show the plan structure.

4.3 Command and control

The purpose of this section is to elaborate Chapter 15 of the National Contingency Plan: Harbour Response.

4.3.1 Powers of harbour authorities

For ship casualty incidents occurring inside the jurisdiction of a harbour authority, the harbour master directs the initial incident response in accordance with the port’s emergency response plans. All harbour masters have powers to direct the time and manner of a ship’s entry into, departure from, or movement within a harbour. These powers include vessels in need of assistance.

4.3.2 Secretary of State’s Representative.

Most incidents will be handled entirely adequately by implementing the local contingency plan and through the combined efforts of the Harbour Master, salvors, ship owners and MCA staff. That said, the Government has appointed the Secretary of State’s Representative (SOSREP) to provide overall direction for all actual and potential marine salvage incidents which may involve marine pollution from ships or offshore installations that require a national response. The National Contingency Plan explains SOSREP’s powers of intervention and if they consider it necessary, they will assume control of a salvage operation, or containment in the case of an offshore installation. (NCP Section 5.5)

The plan must detail clearly the local command and control structure showing how incidents will be managed. Specifically, it must state who will be in overall command and control of the response.

The contingency plan for a harbour authority or oil handling facility must presume that at the outset of an incident occurring in its jurisdiction it will control the incident in accordance with the approved local plan. The harbour authority should keep SOSREP, usually through the CPSO, informed about how the harbour authority’s powers will be exercised to deal with the incident.

In most cases SOSREP may not need to become actively involved. However they will be tacitly approving the decisions and actions being taken and ensuring that they are being taken with a full knowledge of the relevant environmental sensitivities and an understanding of the effects that might ensue. (See NCP sect 15.3 Harbour Master and the SOSREP co-operation)

Notwithstanding, SOSREP, once advised of an incident, cannot ignore a situation. Government policy is that ultimate control of any salvage operation where there is actual pollution or a significant risk of pollution to the UK environment must be exercised by SOSREP. In this situation, an Environment Group (EG) will normally be established as described in the NCP (Sect 9.13). Appointed Environment Liaison Officers (ELOs) will provide environmental and public health advice to the response centres and the relevant harbour authority.

The statutory powers of the Secretary of State empower SOSREP to take over command of salvage operations in certain circumstances. That apart, the exercise of their powers will almost always be confined to exercising “control” of the salvage operation. Furthermore, that control need not be total. It will normally be limited to requiring certain general courses of action to be adopted or avoided. This control need not take the active form by the giving of directions. It may often, take the passive, but nevertheless positive form of monitoring the proposals for, and progress of operations.

It may take the form of being satisfied that the wider public interest in the welfare of the environment is being safeguarded to the greatest possible extent and of lending all possible assistance and encouragement. It is only if there is a difference of opinion as to the best way of serving the overriding public interest that SOSREP will assert responsibility for controlling operations in a more active manner by giving Directions.

A harbour authority should be aware that SOSREP might use the powers of intervention to support them by – for example – directing the ship owner or salvor to assist the local plan. Harbour authorities and oil handling facilities should note that such use of the intervention powers in support of the local plan could still leave the harbour authority or oil handling facility in control.

If (exceptionally) SOSREP felt that the harbour authority was unable to execute its local plan effectively, perhaps because the incident lies outside the scope or scale of the local plan, or the plan is failing to function effectively, SOSREP will use the powers of intervention to take control of the salvage operation. In that event, all those involved will act on their directions rather than those of the harbour authority. SOSREP’s directions overrule any directions issued by the harbour master in respect of the casualty or its cargo. It is crucial that contingency plans deal adequately with this transition. It is likely that resources commanded and controlled up to that point by the harbour master will be required by SOSREP. The contingency plan also needs to provide for the continued function of the harbour so far as possible. This will remain the responsibility of the harbour master, who may also be controlling pollution mitigation measures during the salvage operation. There must be a mechanism to ensure that SOSREP and the harbour master are able to work effectively alongside one another.

Those in command and control of the local plan must be fully aware of any plans for the port held under the National Contingency Plan. It is important that a harbour authority knows what national resources are available, at what notice they can be deployed on-site and how they will be managed. This should be seen as a two-way street as it is equally important for those in command and control of the national plan to be fully aware of the port’s readiness to contribute towards national plans. For example, a port may be able to offer specialist equipment or expertise. Neither the National Contingency Plan nor local plans in their published form can substitute for effective liaison between harbour authorities and the regional CPSO in developing these aspects.

4.4 Escalating incidents

A local plan should be able to function in its initial stages to any incident. The processes of notification, establishing and manning the command and control centre, placing salvage and counter pollution measures on standby or initiating them, and matters like reserving hotel rooms etc., are likely to be similar for most foreseeable incidents.

Sometimes an incident, which at the outset lies within the scope of the local plan, will escalate to the extent where, in spite of assisting efforts, the incident may outstrip the experience and expertise of those in command and control at the local level. It is therefore important that the local plan allows for command and control of a salvage operation to pass to SOSREP in a controlled and predictable way. Similarly the plan should address the mechanisms by which a pollution incident may be escalated to a tier three level of response. Consideration should also be given to the mechanism for passing back control to the harbour authority, within the plan.

4.5 Long-running incidents

The local plan should also make provision for long-running incidents. Not only for incidents which will lie with the harbour authority, but also for incidents in which SOSREP takes command and control of the salvage operation. The local plan can play a vital role in ensuring that emergency duty rosters allow for adequate periods of rest for all involved in the response; locally based and visiting personnel alike. Availability of accommodation and catering facilities should be considered in the plan.

4.6 Exercising

For full details of exercise requirements see Section 8.

The interval between exercises should be determined on the basis of the risk assessment, but as a norm, plans should be exercised to a level that includes the deployment of Tier 2 equipment at least once every three years (Category A and B ports). Where a port, harbour or oil handling facility considers this requirement to be unduly onerous on the basis of the risk assessment, they may submit an alternative exercise programme to the Regional CPSO for consideration and approval, on an individual basis.

It is possible that, due to the geographical area covered or the scope of activities within the port or facility, a single exercise will not sufficiently test the response plan. Careful consideration should be given to ensuring that all those with a role in equipment deployment are embraced by the exercise and that a representative range of the equipment cited in the plan is deployed. It will be for the plan holder to justify to the satisfaction of the Regional CPSO that the programme of exercises does adequately test the full scope of the plan.

4.7 Training

For full details of training requirements see Section 8.

All personnel likely to be involved in a marine pollution incident have to meet specific training requirements and standards. Training requirements will be dependent on size of operation and number of staff. There must be a sufficient number of trained persons to be able to mount a rapid Tier 1 response at any time. Training must be conducted by a Nautical Institute accredited training provider.

5. Consultation approval and control procedures

5.1 The consultation process

Statutory consultees do not approve contingency plans. Their input to plan development is advice, guidance and in some circumstances, provision of regulatory clearances. Any comments provided by these consultees should be confined to matters for which they have formal responsibility. Some of the agencies required to be consulted have to prepare response plans of their own. In order to comment effectively they need the port, harbour authority or oil handing facility’s pollution potential assessment. In particular, they may be able to assist greatly with the assessment of consequences. It is therefore good practice to involve them from the outset in the port plan: it is not good practice to make a first approach with a completed draft.

5.2 Statutory consultees to the plan:

5.2.1 The government fisheries departments:

*Marine Management Organisation (MMO) * Welsh Government Marine and Fisheries * Marine Scotland – Marine Laboratory (MS-ML) * Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD), Fisheries & Environment Division (NI)

5.2.2 The environmental regulator

- Environment Agency (EA)

- Natural Resources Wales (NRW)

- Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA)

- Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA)

5.2.3 The statutory nature conservation body

- Natural England (NE)

- Natural Resources Wales (NRW)

- NatureScot

- Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA)

5.2.4 Local authorities

Borough, district and unitary councils in whose area the facility is situated, or may have impact upon, should be consulted.

Guidance on the consultation process has been issued by the government fisheries departments, summarised in Section 11, by the nature conservation organisations, summarised in Section 9, and by the Environmental Regulators summarised in Section 10.

Statutory consultees should issue their comments on plan content to the plan author with a letter stating that they ‘formally agree with plan content (subject to the following amendments being carried out)’. It is then the responsibility of the plan author to amend the plan if required in accordance with consultee’s requests. If there are any disputed issues, the plan author should contact the consultees and try to resolve the issue(s) or speak directly to the MCA for their advice and guidance. It is the MCA’s intention that wherever possible, disagreements should be resolved through correspondence or personal discussions.

5.3 The approval process

When the plan has been finalised by author, having addressed comments from the statutory consultees, the plan should be sent to the Regional CPSO for approval on behalf of the Secretary of State for the Department of Transport.

The MCA will not accept any plan for the approval process unless the following points have been addressed:

- The plan has been prepared following consultation with the statutory consultees.

- A statement of agreement from each statutory consultee is included in the plan.

- Where the plan covers more than one port, harbour and/or oil handling facility, each party to the plan agrees with its contents and will co-operate in exercising the plan and implementing it following an incident.

A&B Ports – A contract is in place with an Oil Spill Response Organisation (OSRO), providing Tier 2 response services, accredited under a scheme of accreditation that is compliant with the UK National Standard for Marine Oil Spill Response Organisations. This scheme of accreditation must be delivered by a body approved to do so by the MCA and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the currently approved accrediting bodies are the International Spill Accreditation Scheme (ISAS) and the Nautical Institute (N.I.). The Category of Response to which the OSRO is accredited must be appropriate to the Strategies and Actions detailed in the contingency plan in terms of geographic area and type of response. Alternatively, the port can propose an arrangement for an in-house Tier 2 capability or a local area cooperative. Either of these proposals would require MCA approval and any arrangement would need to be accredited in accordance with the relevant Categories of Response in the UK National Standard for Oil Spill Response Organisations.

C&D Ports – The plan details how a Tier 2 spill is to be dealt with and includes details Tier 2 responders who may be contacted for help as required. (See Sect 6.3)

5.4 Issuing approval and validity

The MCA aims to provide comment or issue a certificate of approval within eight weeks of receipt of a fully prepared contingency plan, subject to the need for discussion with the issuing authority and others as required.

A plan is valid for 5 years and has to be revalidated before the fifth anniversary of its previous approval. As in the initial approval process, the plan is to be re-issued to statutory consultees prior to submitting to the MCA for revalidation. In order to secure approval for the revised plan before it lapses, the process of review should commence a year before it is due to expire.

If during this 5-year period changes occur within the operational area of the plan, revisions must be made to the document within three months of these changes occurring.

Any change that has a significant impact upon the effectiveness of the plan, i.e. a change in response strategy, the plan is to be amended accordingly, to be agreed with the consultees and further presented to the regional CPSO. The plan should also be reviewed and amended as necessary following any incident and/or exercise.

5.5 The appeal process

If a submitting authority objects to a direction/notice made by the MCA, on the grounds that any requirement of the direction is unnecessary or excessively onerous or inconvenient, they should endeavour to reach an agreement with the CPSO in the first instance. If they are unable to resolve the situation, an appeal may be made t the Secretary of State within 30 days of the original notice, who will consider the appeal and confirm or cancel it.

5.6 Document production and vontrol

One of the aims of these Guidelines is to promote a consistent approach to plan development. A contingency plan can be written in-house or externally and should follow the format described within these Guidelines. Whilst much of the plan will be textual information; flow diagrams, photographs and charts are an efficient and useful representation of data and their use is encouraged.

A comprehensive Table of Contents will enable any part of the plan to be quickly found.

A supply of report forms (See Section 15) should be kept with the plan and clearly marked for easy location.

5.7 Distribution

Following approval from the MCA, copies should be issued to the full distribution list of the Plan. As a minimum this should include; statutory consultees (for Natural England distribution, in England, an electronic copy of the approved plan should be sent to the Natural England’s Marine Pollution Senior Specialist Kevan Cook [email protected] who will distribute to local teams via Natural England’s internal document filing system. The Tier 2 responder (Category A and B ports), any neighbouring ports / harbours / oil handling facilities, all relevant internal departments and any other appropriate bodies.

The plan is best created and distributed in electronic format (ideally as a single .pdf document). The port/harbour, should maintain the plan in hard copy so that it may be readily referred to during an incident.

Contingency plans are to be controlled documents and adhere to a recognised standard for quality control.

As a controlled document there should be:

- A front cover giving clear details of the plan title, the facility address and contact details, date and plan version number

- The page number, date of issue and version number to be in the footer of each page

- Within the plan, the nominated plan custodian

- A list of plan holders or locations where plans are held.

- A document revision record – updated at each amendment.

5.8 Plan amendments

If issued electronically, the amended plan is to be updated to reflect the change (including the version number) and reissued in full to each plan holder. If in paper format, issue the amendment with full instructions as to how the amendment is to be applied and recorded.

The MCA requires two controlled copies of the Plan – and of any amendment made to it for distribution to:

- The associated Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC)

- The Counter Pollution and Salvage Branch at MCA Headquarters

MCA copies to be distributed by email or on CD/DVD

In accordance with the Freedom of Information Act, copies of the plan should be made available to the public on request. This should not include personal details which may be held within the plan.

6. The OPRC regulations

6.1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1998 No.1056

The Merchant Shipping (Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation Convention) Regulations 1998, As amended by SI 2001 No.1639 and SI 2015 No.386.

The 1998 OPRC Regulations are the principal legislation on counter pollution from a harbour authority and oil handling facility perspective.

The OPRC obligation arises for:

Category A port

Any harbour for which there is a statutory harbour authority having an annual turnover of more than £1 million.

Category B port

Any harbour and any oil handling facility offering berths alongside, on buoys or at anchor, to ships of over 400gt or oil tankers of over 150gt

Category C port

Any harbour and any oil handling facility which the Secretary of State has served the harbour authority or operator with a notice stating that they are of the opinion that maritime activities are undertaken at the harbour or facility which involve a significant risk of discharge of over 10 tonnes of oil.

Category D port

Any harbour or oil handling facility in respect of which the Secretary of State has served the harbour authority, operator (as the case maybe) a notice stating that they are of the opinion that it is located in an area of significant environmental sensitivity, or in an area where discharge of oil or other substances could cause significant economic damage.

The obligation in the Regulations relates to pollution by oil spilt in harbour waters from vessels. The requirement is to hold a plan to remove oil pollution from the harbour waters and, from structures and shoreline owned by the harbour authority. Cleaning other shoreline areas is assigned to local authorities and landowners.

Each harbour, port or oil handling facility, to which the legislation applies, shall within its capabilities either individually or through bilateral or multi-lateral cooperation as appropriate with the oil and shipping industries, neighbouring port authorities and other relevant bodies establish:

- Detailed plans and communication infrastructure for responding to an oil pollution incident.

- A minimum level of pre-positioned oil spill combating equipment, commensurate with the risk involved. Such equipment and expertise to be available at all times. This resource must also be available to those responsible for the execution of the National Contingency Plan

- A sufficient number of people trained to the appropriate level to both co-ordinate the response and mobilise the equipment.

- A programme of exercises to maintain proficiency in the execution of the plan. Such exercises to be recorded and evidence to be available to the Secretary of State if required.

6.2 Non-compliance process

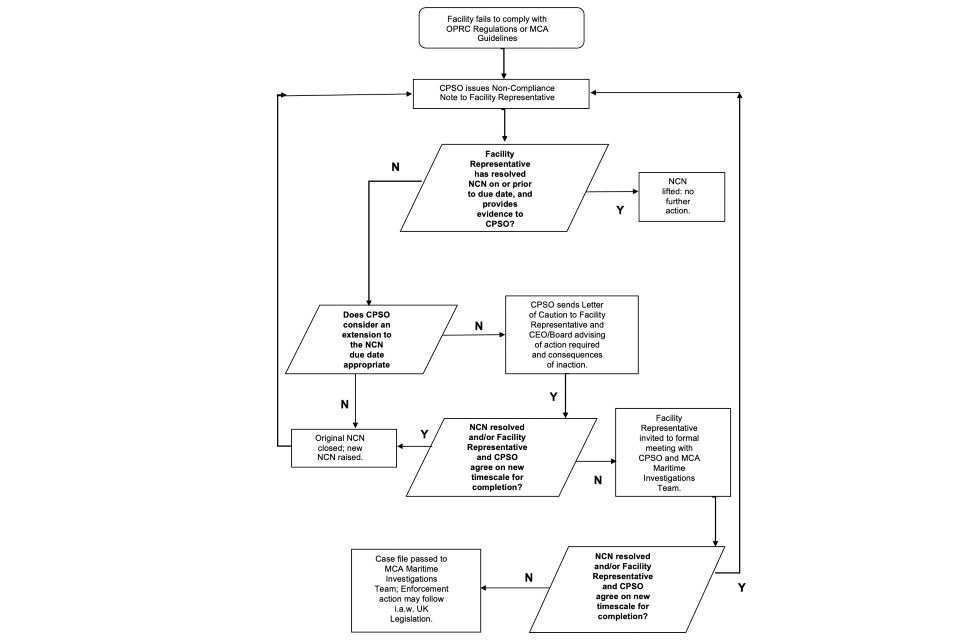

If a port, harbour or oil handling facility is found to be deficient in its obligations under the 1998 OPRC Regulations, or these Guidelines, the regional CPSO may issue a Non-Compliance Note. Failure to resolve a non-compliance may result in enforcement action. The process is outlined in Appendix 14.9.

6.3 Tiers of response

For the purpose of planning, tiers are used to categorise oil spill incidents. The tiered approach to oil spill contingency planning identifies resources for responding to spills of increasing magnitude by extending the geographical area over which the response is co-ordinated:

Tier 1 - Local (District)

Tier 2 - Regional (County)

Tier 3 - National

The tier classification system can also be defined as follows:

| Tier | Definition |

|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Small operational type spills that may occur within a location as a result of daily activities. The level at which a response operation could be carried out successfully using individual resources and without assistance from others. |

| Tier 2 | A medium sized spill within the vicinity of a company’s location where immediate resources are insufficient to cope with the incident and further resources may be called in on a mutual aid basis. A Tier 2 incident may involve Local Government. |

| Tier 3 | A large spill where substantial further resources are required and support from a national (Tier 3) or international co-operative stockpile may be necessary. A Tier 3 incident is beyond the capability of both local and regional resources. This is an incident that requires national assistance through the implementation of the National Contingency Plan and will be subject to Government controls. |

The level of response will be broadly dependent upon this Tier classification. However, the specific response to a pollution incident may require additional support and resources. In general it is unrealistic to expect every port / harbour or oil handling facility, to maintain an adequate capability to mitigate the effects and consequences known to occur during an oil spill incident at Tier 2 level and above. Accredited Tier 2 Responders have prepared for, and are capable of, providing this service on a contractual basis.

Harbour authorities and oil handling facilities should have in place sufficient equipment of their own to adequately deal with what the regulations term a Tier 1 response.

6.4 Tier 2 response – A&B and C&D ports

There must also be a plan to deal with up to Tier 2 spills as follows:

Category A and B ports - the MCA requires that an agreement is in place with an accredited responder to provide a declared response to a set standard or set criteria. Alternatively, a port may elect to provide their own Tier 2 response, in which case they will be subject to the same accreditation process. (See ‘Consideration for a Tier 2 Response’ below)

Category C and D ports - there is no requirement to have a contract with a provider but the plan must detail how a Tier 2 spill will be managed. This will involve having identified accredited responders and maintaining their emergency contact details.

The effect of these provisions is to limit the quantity of spilled oil for which a harbour authority must plan removal. Harbour authorities’ plans may provide for a larger response capability, subject to approval of such plans.

The level of response and response equipment required to comply with OPRC legislation should be detailed alongside any existing agreements with a contractor to respond on behalf of the plan owner.

6.5 Consideration for a tier 2 response

6.5.1 The plan

Every OPRC compliant port, harbour or oil handling facility has the choice of preparing their contingency plan either in-house or by employing a contractor to prepare the plan for them.

6.5.2 Tier 2 response arrangements

Whether a port has contracted an Oil Spill Response Organisation (OSRO) to provide Tier 2 response services, has developed an in-house Tier 2 response capability or has entered into a local cooperative arrangement, Tier 2 response arrangements must be accredited under a scheme of accreditation which is compliant with the UK National Standard for Marine Oil Spill Response Organisations. This scheme of accreditation must be delivered by a body approved to do so by the MCA and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the approved accrediting bodies are the International Spill Accreditation Scheme (ISAS) and the Nautical Institute (N.I.). The Category of Response to which the OSRO, in-house capability or local cooperative arrangement is accredited must be appropriate to the Strategies and Actions detailed in the Contingency Plan in terms of area of response and type of response.

If the port does opt to develop an in-house Tier 2 Response Capability or enter into a local cooperative arrangement, the Regional CPSO should be notified to discuss these arrangements prior to them being implemented.

6.5.3 Exercise and training

A tier 2 response requires a programme of on-going exercises and training for maintained proficiency and continual improvement. The programme should include hands-on equipment deployments, site familiarisation and communications exercises. The possibility of integrating exercises with nearby/local facilities sharing a Tier 2 response contractor (if applicable) should be considered. (See Section 8 for full details for training and exercise requirements)

6.5.4 Availability requirements

The plan should take account of the following requirements regarding availability:

- A clear method of authorising a response

- The response system must cover 24 hrs / 365 days a year

- Immediate expert advice and guidance on equipment deployment

- Response time: within 6 hours (or as agreed by the MCA)

- Call out procedures for response personnel

- Mobilisation of appropriate equipment and travel time to the spill location should be realistically achievable

- Where Tier 2 response is provided from a specific response centre, the ability to back up the resource in the event of a second response call on the centre is essential.

- Back-up resources for long running incidents - throughout the response phase and during recovery, cleaning and repair of used equipment.

6.5.5 Additional requirements

Additional resources needed to cope with a Tier 2 spillage can include mutual help agreements with other ports, oil companies and local authorities, and resources may also be available from oil spill contracting companies. The harbour authority has to demonstrate in the plan and through the arrangements they have made that they can deal with a Tier 2 response. It is prudent to share with other local interests’ information about the external resources being relied upon – if only to ensure that they are not double-counted. All Tier 2 responders must be capable of conducting a complete and thorough site specific risk assessment for the site. When undertaking this task, the following points will be among those to be considered:

- Perceived oil spill risks

- Health and safety issues

- Environmental concerns (including interim storage and waste disposal).

- Access routes etc;

- Booming plans developed to protect prioritised environmentally

- Sensitive areas in the region concerned

- Other relevant emergency plans covering OPRC and adjacent areas.

6.5.6 Personnel

The plan should consider the following personnel matters so that:

- Sufficient personnel are available to provide an adequate response and safe operations;

- Staff are familiar with the port environment;

- Staff are mobile;

- A supervisory structure is in place;

- Staff training requirements are met - familiarity with equipment handling, and

- Staff participate in exercise programmes.

6.5.7 Equipment

Regarding the provision of equipment, the plan should ensure:

- The suitability of generic packages or specific packages (inshore / offshore);

- Its ease of deployment;

- That it is fit for purpose, reliable and supported by the manufacturer.

6.5.8 Information to Tier 2 responders

During a response operation additional information should be readily available to the Tier 2 responders who will be in communication with the Harbour Authority or oil handling facility. This information should include:

- Directions to the site

- Key personnel with contact details

- Number of port or harbour personnel who may be able to help

6.5.9 The Implications of not having a tier 2 Response

If a port / harbour or oil handling facility is considered to be included under the OPRC regulations then failure to have a tier 2 response established may result in enforcement action by the MCA that may lead to prosecution.

7. Structure of an OPRC plan

7.1 The four sections of a contingency plan:

-

Preamble – an introduction to the plan as well as providing aids to navigation and understanding of the plan.

-

Strategy section – the scope and statutory requirement for the plan and how it will be implemented. This section should be used for reference and for planning.

-

Action section – the means with which to implement the plan – instructions and emergency procedures which allow for rapid mobilisation of resources such as notification flow charts and individual action cards.

-

Data section – supporting information to enable decisions to be made and subsequent actions to be undertaken. Contact details, maps, charts, environmental data etc.

The following sections suggest the information that should be contained within each section.

7.2 The Preamble

-

Title page

- document title

- address and contact details

- date and version number

-

Table of contents

- Either by section/part or page number

-

List of plan holders

-

Amendment record

-

List of abbreviations

- not mandatory but good practice

7.3 The Strategy section

-

Statutory requirement to maintain a pollution plan

- i) Policy statement

- ii) Environmental statement

- iii) Purpose of the plan

-

Responsibility for upkeep of the plan and its routine review

- i) Person nominated as the plan owner

- ii) Obtaining approval of statutory consultees and MCA validation

- iii) Any other bodies consulted in the production of the plan

- iv) Routine reviews of the plan through its life – following incidents or exercises for example

- v) Five-yearly revalidation process.

-

Geographical boundaries / jurisdiction limits

- These may be taken from the authority’s enabling legislation and should be drawn clearly on a map / chart. (If maps or charts are used a copyright licence must be obtained from the originator.)

-

Interfacing contingency plans

- i) Identify council, emergency and any other relevant existing plans that abut or impact this plan. Plans for oil handling facilities and installations within a port / harbour should dovetail with the port / harbour authority contingency plan

- ii) Tier 2 response may be shared between installation and port / harbour, or be separate. If separate, the Tier 2 response must meet the criteria described on page 30 and all details should clearly reflect the pre-agreed arrangements between the installation, the port / harbour and the Tier 2 responder.

-

Details of the port/harbour or oil handling facility ie a full description of the port/harbour – to include but not exclusively the following:

- i) Approach and entrance

- ii) Hazards – shoals, tides, adverse winds

- iii) Maximum size of vessels that can be accepted – draught, length, beam

- iv) Anchorages, berths and moorings

- v) Repair and harbour facilities

- vi) Cargo handling facilities

- vii) Road and alongside access for vehicles

- viii) Bunkering arrangements and oils encountered.

- ix) Annual vessel movements

- x) Cargoes shipped through the port and quantities

- xi) Any special or other activities.

-

Summary of risk assessment

- i) A risk assessment based on the types of oil likely to be encountered together with the activities carried out within the port/harbour.

- ii) The use of a probability v consequence chart may be useful. Include any land-based sources that may impact harbour waters

-

Other organisation responsibilities

- Details of all authorities and organisations who have a role to play in the event of an oil spill incident should be included within this section

-

Place of Refuge

- An assessment of the port as a place of refuge noting what type of vessels could perceivably be accepted and under what limiting conditions

-

Health and Safety

- i) Responsibility to employees, visitors, contractors and the environment in general

- ii) Note special considerations for employees engaged in clean-up activities, especially prolonged campaigns

-

Categories of incident

- i) Description of the Tier system with local relevance

- ii) Clearly show who has authority to initiate a response and escalate a response from T1 to T2

-

Incident organisation

- i) The responsibility of key personnel at each Tier, describing the role of the Oil Spill Management Team (OMT) and how, when and why this would be established. Also who is to be involved and at which Tier level

- ii) Clear indication of who has responsibility in the harbour master’s absence

-

Tier 1 response (A, B, C & D ports)

- i) Number of trained responders at Level 4/5P and Level 1P

- ii) Guaranteed response and mobilisation time

- iii) Tier 1 equipment – type, quantity and location(s).

-

Tier 2 response

- i) For an A/B port – detail who is providing the service, the response time and capability

- ii) For a C/D port – Arrangements for dealing with a Tier 2 type incident. To include – identification of T2 responders (contact details to be held in the Contacts Directory) and any MoU with an adjoining A/B port to provide mutual support

-

Incident control arrangements

- i) Establishing and identifying a location for a :

- ii) Marine Response Centre (MRC)

- iii) Salvage Control Unit (SCU)

- iv) Environment group,

- These Response Units are described in detail in the NCP Sect 9.10

-

Details of action

- Details of the strategic approach required for any incident i.e. prevention, containment, recovery, dispersal and the waste management principles of waste prevention, waste minimisation, waste segregation, reuse, recovery and disposal

7.4 The action section

-

Introduction

- i) How to use this section of the plan

- ii) Introduction to the roles and responsibilities of those who may be involved in a pollution response incident – First Informant, On-scene co-ordinator, Incident Manager for example.

-

Courses of action

- A flow chart (or similar) detailing the required actions and notifications during any type of pollution incident.

-

Action cards

- The roles, responsibilities, initial and subsequent actions of all personnel likely to be involved (see Section 15.3) (If copied and laminated, these cards can be used as an aide-memoir.)

-

Call out procedures

- Details of mobilisation procedures for internal staff and external contractors (Tier 2 response).

-

Notification of external authorities

- Consideration of other authorities who will/may need to be notified. These may include:

- i) HM Coastguard

- ii) Environmental bodies

- iii) District and County Councils

- iv) Adjoining land owners

- v) Other commercial / recreational activities

- Consideration of other authorities who will/may need to be notified. These may include:

-

Record keeping and reporting

- i) Requirement to maintain strict records and inform the relevant authorities.

- ii) Personal log sheets (See Sect 15.2)

- iii) CG77-POLREP (See Sect 15.1)

- iv) Tier 2 contractor briefing / tasking form

- v) Pollution sampling instructions (STOp 04/2001 - under revision Sept 2020)

-

Response Guidelines

- i) To establish the true extent of situation by investigating the precise type and quantity of released oil and if ongoing.

- ii) Identify immediate response priorities – mobilising or placing resources on standby. Include, identification of environmental, commercial and recreational sensitivities as collated within the relevant data section of the plan. (See Section 9 for Nature Conservation Organisation guidance).

- iii) For each priority site, establish which resources will be utilised and how - this may include recourse to pre-defined booming plans and/or tactical response plans. (Give access routes and grid references (and/or post codes if appropriate) to mobilisation and laydown areas or other key points)

- iv) Philosophy and objectives behind pre-agreed strategies for response at sea, within coastal zones and on shorelines including limiting factors and adverse conditions.

- v) Identification of interim waste storage sites, treatment sites and disposal options. (See section on Waste Management )

- vi) A method for predicting the fate of spilled oil should be provided which may include the results of modelling exercises, where appropriate. If modelling is considered to be a useful predictive tool, ports should identify those with capability to undertake such a task.

- vii) Consideration should be given to places of refuge and beaching areas for the stabilisation of stricken vessels, see paragraph.

-

Dispersant

- If dispersant use is an option to be considered, all relevant details should be included – e.g. locations where dispersant use is appropriate and conditions of use, copy of the standing approval (if applicable). See MMO guidance (Sect 12) and requirements on dispersant spraying.

-

Communications

- i) Detail communications between internal personnel and external bodies including details of communications between harbour/port/oil handling facility personnel and the Tier 2 response contractor whilst on and off site.

- ii) Suggest a diagram with job titles and organisation names, method of communication during working hours and outside working hours, fully detailed.

-

Press details

- Details of media guidelines, including:

- i) routing of media enquiries,

- ii) personnel responsible for talking to the press,

- iii) location where press will be situated,

- iv) communicating with other stakeholders’s press teams

- v) SITREP template

- Draft “holding” statement confirming that an oil pollution incident has occurred.

- Details of media guidelines, including:

-

Health and safety

- i) Details of all health and safety related issues. These should relate to all health and safety issues but particularly, consideration of specific oil spill related hazards.

- ii) If this information already exists, name the documents and refer to their use.

-

Waste management

- i) The plan must fully comply with the requirements of the Environmental Regulator’s policy with regard to the management of wastes in an emergency. A copy of this policy is included in Sect 10 - ‘Guidance from the Environmental Regulator’.

- ii) Any existing waste management plans should be referenced, along with any locations of pre-agreed waste disposal sites (waste disposal and storage sites must be approved by the environmental regulator.)

- iii) The importance of informing the statutory nature conservation bodies of proposals to dispose of or store oily waste material to ensure that local wildlife sites are not affected needs to be stated here. Proposals for waste segregation and minimisation should be addressed.

- iv) The environmental regulator will provide guidance as to routes and methods of waste disposal. Any pre-agreements to be recorded in the plan.

- v) If no waste disposal strategies are in place the following should be agreed in consultation with the Environmental Regulator:

- Sites for the interim storage of waste

- Where could waste be treated or disposed of – locally and regionally?

- What methods of treatment are available?

- What types of waste can be handled?

- Are there any restrictions on the volume of waste that can be handled?

- Is the waste disposal facility privately or publicly owned?

- Are there any permits required to utilise the facility?

- What are the requirements for waste containers?

- How can waste be transported to the facility together with any waste transfer permits that will be required?

7.5 The data section

-

Contact directory

- i) All contact details should be in a tabular format

- ii) Contact details should not contain names of personnel – only organisation names or job titles. This keeps the plan current and amendments will not have to be made every time there is an employment change. Personal contact details should only be included with the owner’s permission and in line with GDPR legislation.

-

Training

- i) Ports / harbours and oil handling facility staff who have or are likely to have any involvement in an oil spill incident require training from a provider accredited by The Nautical Institute. See -

- ii) Full details of training requirements – Section 8

-

Exercises

- Outline the exercise requirement for the category of port and any pertinent information relating to exercises e.g. seasonal suitability, priorities and involvement of other stakeholders.

-

Environmental, commercial and recreational sensitivities

- i) The possible response options outlined above will have to be established with the relevant authorities. Ecological, commercial and recreational concerns should be carefully considered.

- ii) In this section of the plan the consequences of applying or not applying a technique should be fully discussed and understood by all parties.

- iii) In practice an incident could involve the use of a variety of response techniques and a key decision in some instances may be whether or not to use dispersants.

- iv) If dispersant is an available option this should be clearly stated and the restrictions upon its use explained. Reference should be made in the response strategy section of the plan. A copy of any standing approval should be included within the plan.

- v) The effectiveness of any response operation varies with sea and weather conditions. The response strategy section of the plan should reflect this and oil spill movement prediction should take differing environmental and meteorological conditions into consideration. This information can be combined with the resources available and provide a realistic assessment for protection and clean-up strategies applicable to the location.

- vi) This section of the plan should clearly identify areas of environmental, commercial and recreational sensitivity and their importance including:

- vii) Identification of different types of shoreline and habitats to be encountered and the response (clean-up) strategies applicable to each. This information should be as thorough as possible illustrating the reasoning behind pre-agreed strategies and illustrating the impact of season and how this may affect and alter the structure of the environment and the applicable clean-up strategies. Information regarding environmental prioritisation of areas, should be obtained from the Local Authorities in conjunction with environmental groups. This data will enable the assessment of short term economic and amenity value against the longer term ecological value. The use of maps and charts to illustrate these areas is encouraged.

- viii)Relevant details of waste disposal facilities. This information should refer to local and on-scene facilities, all other waste disposal strategies should be contained in the waste disposal section of the plan.

- ix) Access routes – a map would be ideal.

- x) Wildlife interests, details of flora and fauna, seasonal affects and locations within jurisdictional limits.

- xi) Commercial activity details, including fishing, water intakes serving aquariums and fish storage facilities and other mariculture activities.

- xii) Recreational activity - locations, types and number of vessels using the location and seasonal impacts.

- xiii) Environmental sensitivity mapping. Maps should be clear and illustrate any areas discussed within the environmental section of the plan. This should include wildlife habitats, commercial, recreational, fishery activities and seasonal changes.

- xiv) Status of the local Environment Group including key contact points for liaison and advice from local contacts or if not available then the contact point for national Statutory Nature Conservation bodies.

-

Counter pollution resources

- i) Details of available resources.

- ii) Tier 1 – including manpower, and equipment held on site or locally available. Details of key holders should be maintained for locked facilities.

- iii) Tier 2 details should follow the format above (if contractor, state name and generic equipment list, location of response base(s), estimated response time and back up facilities).

-

Appendices

- i) Information to support the plan should be contained in the appendices.

- ii) Material Safety Data Sheets for any product likely to be encountered within the location, or as part of the response.

- iii) Supporting documentation of a Tier 2 response contract, if appropriate. This may be in the form of a contract signed by the relevant harbour/port/oil handling facility and by the contractor. If port/harbour/oil handling facility has an inhouse Tier 2 response capability then the MCA must approve the facility and the equipment stockpile and there must be a document signed by the MCA stating that they are in agreement with this.

- iv) Evidence of consultation. All statutory consultees must produce evidence of agreement with plan content (this letter may state that the consultee is in agreement with plan content subject to amendments being carried out).

8. Exercise and training

8.1 Introduction to exercises and training

The ultimate test of any contingency plan is measured by performance in a real emergency and the effectiveness of the plan should be examined in the light of any actual oil spill emergencies which occur. It may be that activation of the plan to a real event may negate the requirement for a subsequent exercise of the plan. However, notwithstanding such events, the plan must be tested regularly, through a programme of realistic exercises.

8.2 Annual returns

Ports, harbours and oil handling facilities should provide an annual return for the previous period, to the regional CPSO no later than 31 January. The annual return should include brief notes on:

- Notification, mobilisation and tabletop exercises

- Tier 2 Incident Management Exercise, or date of most recent.

- Summary of current level of staff training to MCA 1-5P

- Summary of actual pollution incidents during the period

A template annual return is provided at Appendix 15.5

8.3 Exercises

The following provides guidance on planning and conducting exercises which have been designed to evaluate the contingency plan and include a degree of training for any personnel likely to be involved in an oil spill incident. Each port / harbour / oil handling facility must participate in exercises in accordance with the provisions within their OPRC compliant oil spill contingency plan.

The objectives of any exercise need to be pre-agreed, enabling the exercise planners to tailor the exercise to the needs of the players. For example, it may be desirable for different aspects of the plan to be exercised separately such as notifications or equipment mobilisation/deployment. A larger exercise, encompassing all aspects of the response, may not explore the detail of each of these individual themes but will help promote a wider understanding of the purpose and scope of the whole plan. Whatever the scale or type of exercise, the invited participation by the appropriate environmental and regulatory authorities, and others, will aid the collective understanding of the plan, to the benefit of all involved.

8.4 Types of counter pollution exercise

Notification exercise

Used to test alert and call-out procedures for response teams, test communication systems, availability of personnel, evaluate travel options and arrangements and test the transmission of information. This may be an announced or un-announced exercise and will confirm the validity of contact information within the plan and should be carried out twice per year.

Mobilisation exercise

May be used to test the actual mobilisation times of individuals and contracted resources. Ideally mobilisation should be tested without prior warning, although the requirement for an unannounced callout will need to be balanced against the practical difficulties and financial penalties of doing so. Whilst this important aspect of the response may be exercised in isolation, it may be seen as beneficial to incorporate this as a specific objective within the scope of another of the framework exercises. This exercise should be carried out twice per year.

Table-top exercise

Whilst the degree of complexity can be decided upon by the exercise coordinator, a table-top exercise can be used to test the emergency management knowledge and capability. It provides individual and also team training, enabling personnel to be familiarised with the various roles and responsibilities and identification of resources. A table-top exercise can also explore the interaction between the different parties involved, particularly by testing the principles of the response strategies. These exercises can be used to test co-ordination with local authorities and the emergency services. Some organisations, which have peripheral responsibilities, may be roleplayed.

During this exercise the capability to respond to a Tier 2 type spill and initiate the primary actions in the event of a Tier 3 response can be put to the test. As discussed above, it can be effective to combine this exercise with an equipment mobilisation / deployment exercise, but in any case a table-top exercise of the incident management structure should be incorporated within the exercise programme at least annually.

Incident management exercise

These exercises can test the capability of local teams to respond to Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3 type incidents, providing experience of local conditions and spill scenarios, enhancing individual skills and teamwork, integrating the roles of external bodies and organisations. MCA considers that each Category A&B port, harbour and oil handling facility must hold an Incident Management Exercise, incorporating equipment deployment to a Tier 2 level at least every three years unless a different timescale had been agreed with the Regional CPSO during initial plan approval.

This is likely to incorporate, or be combined with the notification and mobilisation exercises as mentioned above. Such exercises need, so far as possible, to involve actual participation by associated organisations to represent a real emergency. However, if this can not be achieved, role-playing personnel can be used to simulate roles and responsibilities.

8.5 A Balanced programme of exercises