SD3 How to be a property and affairs deputy (web version)

Updated 21 March 2023

Applies to England and Wales

1. Getting started

This guide is for deputies appointed by the Court of Protection to make property and finance decisions for people who don’t have mental capacity to make such decisions themselves.

Being a deputy is an important responsibility. The court order sent to you by the Court of Protection says who you are authorised to make decisions for and in exactly which areas.

Please make sure you read and fully understand the court order. If there’s anything you don’t understand, contact the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG).

If this is all new to you and feels a bit daunting, don’t worry, you’re not alone. If you need help making a decision, discuss it with your case manager at OPG, family members or a financial adviser to get their views.

In this guide we use other deputies’ stories to show some things to consider when making decisions. These aren’t final answers but may give you ideas about how to act.

An A-Z jargon buster at the end of this booklet explains terms you might not understand.

Throughout this guide, we refer to ‘the person’ whose property and finance decisions you are making. Elsewhere, you’ll sometimes see them called – more officially – ‘the client’

2. What does OPG do?

OPG is a part of the government that supports you in your role as a deputy and makes sure you’re acting in the person’s best interests.

You’ll have two early stages of contact with OPG:

-

Once you’re appointed as a deputy, you’ll get a short, introductory phone call. In the conversation, a case manager will book a longer, ‘settling-in’ call, which can last up to an hour.

-

During the settling-in call, your case manager will discuss such things as:

-

the terms of your court order

-

the person’s current finances

-

what you should and shouldn’t be spending money on

OPG has lots of useful information about being a deputy, but it can’t give legal or financial advice – for that, speak to a solicitor or accountant.

PO Box 16185

Birmingham B2 2WH

Phone: 0300 456 0300

Email: [email protected]

Monday to Friday 9am to 5pm; Wednesday 10am to 5pm

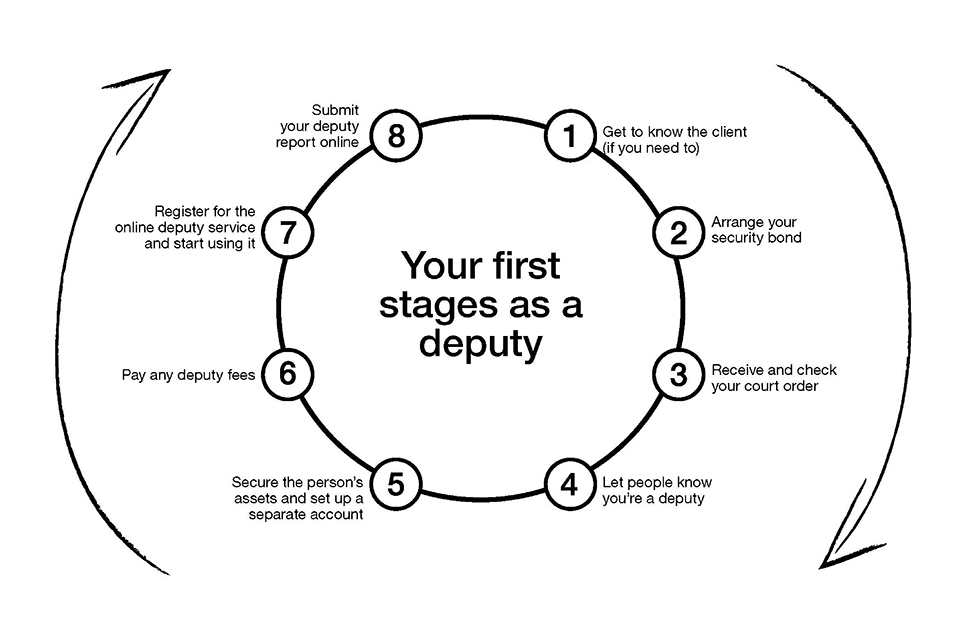

3. Your first stages as a deputy

1. Get to know the person you’re making decisions for

If you didn’t already know the person you’re acting for as a property and affairs deputy, you should start getting to know them now. The main rule in making property and finance decisions for the person is that those decisions must always be in their best interests.

Your decisions must be in keeping with the size of the person’s estate – their property and finances – but there are other things to think about, too. If the person sometimes has mental capacity and sometimes doesn’t (‘fluctuating capacity’), make a note of the sorts of decisions they make when they do have mental capacity.

If the person once had mental capacity but doesn’t now, consider what kinds of financial decisions they made when they did.

Ask other people, such as close friends and relatives, about the person’s likes and dislikes, wishes, beliefs and past decision-making if they once had mental capacity. Use all these sources of information to guide your decision-making as the person’s deputy.

2. Arrange your security bond

Property and affairs deputies may have to pay a security bond before the Court of Protection will send their deputy order.

The purpose of the bond is to protect the estate of the person you’re acting for if you fail to perform your deputyship duties. The court will tell you if you need to pay a bond.

The court sets the amount of the bond based on such things as:

-

the size of the person’s estate

-

the kind of access you have to it

You pay the bond from the person’s funds (or you can pay it and then pay yourself back once you have access to the person’s estate).

If you need to pay a security bond, you can’t start acting for the person until you’ve paid it.

Bond companies

The Court of Protection recommends an approved bond company that is checked regularly to make sure it meets the right standards.

You can choose another bond company but make sure it meets the standards the government sets – call OPG for advice. A letter from the court will tell you how to pay your bond.

You have to apply to the Court of Protection, not OPG, if you think your bond is set at the wrong level.

3. Receive and check your court order

Court orders are different for each deputyship. When the Court of Protection sends your order, make sure you’re familiar with the exact kinds of decisions it says you can make for the person.

Common kinds of decisions that property and affairs orders cover are:

-

paying for care, for example a nursing home

-

buying or selling property

-

making investments

-

giving gifts

-

providing for dependants

Read through the court order carefully to check for errors such as names spelled wrongly. If there are any, contact the Court of Protection immediately to have them fixed.

For more serious errors, you’ll need to fill in and send the court a COP9 form. Send it to the court within 21 days of the date the order was sent to you.

If you haven’t told the court of any errors within 21 days, you may get charged for another application to fix the problem.

You can only make decisions for the person in areas the Court of Protection has authorised. If you want to make other decisions, you need to apply to the court to change your deputy order.

4. Let people know you’re a deputy

You need to let certain individuals and organisations the person is involved with know that you’re the deputy. This is called ‘registering’ the deputyship. Some examples are:

-

Department for Work and Pensions for state pension or benefits the person qualifies for

-

banks/building societies/life assurance companies/National Savings & Investments

-

payer of any private pension(s)

-

solicitor who holds the person’s will and/or property deeds

-

care or nursing home, or hospital

-

local authority – for housing benefit or local authority help with fees

You need to show any financial bodies you deal with for the person:

-

an original, sealed copy of the deputy order (they may not accept photocopies)

-

proof of your, and the person’s, name and address

If you need to send your deputy order somewhere when registering your deputyship, ask for it to be returned or you may run out of copies.

You can get more copies, costing £5 each, from the Court of Protection.

5. Secure the person’s assets and set up a separate deputy account or accounts

Once you have access to the person’s accounts and know their sources of income and assets, you can make a full list of what’s in their estate. Pay any outstanding bills and cancel any payments if they no longer apply.

Separate accounts

Most deputies set up a separate account or accounts to avoid confusing the person’s finances with their own. Once you have a separate deputyship account, you could arrange Direct Debits to make it easier to manage the person’s regular payments.

Sometimes there’s a good reason not to keep the person’s finances separate. For example, you may be your wife or husband’s deputy and have held a joint account for many years. Discuss with your case manager at OPG whether to keep a separate account, if you’re unsure.

6. Pay any deputy fees

You pay OPG’s fees for supervising your deputyship from the person’s funds, not your own. The fees include:

-

a one-off deputy assessment fee of £100

-

a yearly supervision fee of £320

If the person has a low income, you can apply for an ‘exemption’ (paying no fee) or ‘remission’ (paying a lower fee) of the assessment and supervision fees.

Assessment fee

This one-off fee is for assessing the circumstances of each deputyship. OPG asks for payment of the fee early on in your deputyship. If you pay the fee before you have access to the person’s funds, you can pay yourself back later.

Supervision fee

There is also a yearly fee of £320 to cover the cost of supervising your deputyship. This is sometimes reduced – to £35 – after the first year of your deputyship if the person’s assets are worth less than £21,000 and closer supervision isn’t needed.

Supervision fees are billed towards the end of the financial year, in April. In your first year, you only have to pay for the proportion of the year you’ve been deputy.

Find out more about fee exemptions and remissions, along with an application form to pay less.

7. Start recording decisions and transactions

Keeping financial records is one of a deputy’s duties under the law – you include them as part of the deputy report you submit at least once a year.

Using the online reporting service (see below), you should start recording transactions and decisions about the person’s property and finances as soon as you can. Decisions might include:

-

making an investment on the person’s behalf

-

selling some of their assets

-

using the person’s funds to buy someone a gift

If you consulted other people about a financial decision, note that in your online report, too.

Where possible, keep receipts, bank statements and invoices as a record of your spending. OPG may ask you to submit these when it reviews your deputy report.

You don’t need to keep a record of the person’s own spending if they have a small allowance or pocket money.

8. Submit your deputy report online

As your court order states, deputies need to complete a report at the end of every year of their deputyship. Sometimes OPG will ask you to report for a shorter period.

You fill in your deputy report online. The online service lets you record decisions and transactions as you go along, meaning there’s less to do at the end of the year.

You can register for the online service as soon as you have your deputy case number from OPG.

If you have trouble reporting online, you can call OPG’s deputy team on 0300 456 0300.

OPG uses your report to check the person’s funds are being spent in their best interests and to monitor your involvement with the person. Your report should include:

-

significant financial decisions you made on behalf of the person

-

how you involved the person (if possible) in decision-making

-

details of all the money the person has got during the year

-

payments you’ve made on the person’s behalf

-

the current value of the person’s assets and investments

OPG will send you a reminder to submit your deputy report.

If you don’t submit your report when OPG asks for it, or if OPG has other concerns about it, we will review your deputyship. Ultimately this could lead to us applying to the Court of Protection to remove you as a deputy and appoint another deputy instead.

The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 Code of Practice has lots more detail and examples about how deputies can act.

You can order or download a copy

4. Your role as deputy

What does mental capacity mean?

‘Mental capacity’ means the ability to make a specific decision at the time it needs to be made. A person with mental capacity has at least a general understanding of:

-

the decision they need to make

-

why they need to make it

-

any information relevant to the decision

-

the likely consequences of the decision

They should be able to tell other people about their decision through speech, gestures or other ways, such as voice-activated equipment.

People can sometimes make certain kinds of decisions but don’t have the mental capacity to make others. For example, someone may be able to decide what groceries to buy but be unable to understand about making financial investments.

Mental Capacity: five principles

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 – which governs what deputies can do – sets out five rules about mental capacity. The rules affect you as a deputy in these ways:

-

The person should make decisions for themself unless you can show that they’re unable to make them.

-

You need to give the person all the help they need to make a decision before deciding they can’t make that decision.

-

If the person makes what seems to be an unwise or odd decision, that doesn’t mean they lack capacity to make it. (Many people make unwise decisions from time to time.)

-

Any decision you make for the person must be in their best interests – a very important point explained more below.

-

Anything you do on behalf of a person who lacks capacity should restrict their basic rights as little as possible.

Example: Telling when someone has mental capacity*

Khaled has bipolar disorder and in the past has gone on spending sprees that have left him heavily in debt. The Court of Protection has appointed his father, Ali, as his deputy for property and affairs.

Khaled has inherited some money from his uncle, and his father wants to know if he can contribute to decisions about how to spend it. His father thinks the money would be best put towards buying Khaled a flat of his own to live in.

In the past, when asked about big spending decisions, Khaled has wanted to make inappropriate purchases – given the small size of his estate – such as sports cars and luxury holidays. This time, however, Khaled seems to show a good understanding of the pros and cons of buying his own flat.

Ali decides Khaled has mental capacity at this time to contribute to the decision about buying a property. Khaled agrees buying his own flat would be a good way to spend his inheritance.

* The examples in this guide use imaginary characters and situations to help you to make decisions as a deputy

How can I help the person make a decision for themselves?

People may have mental capacity some of the time but not all of the time. If the person is usually liveliest in the evening, for example, that may be the best time to involve them in decision-making.

The person may also be more responsive if you choose the right setting to ask about decisions – perhaps at home, rather than in an unfamiliar environment.

You could also use other ways to communicate. Try using pictures or sign language to explain a decision, for example.

Sometimes the person may just need more time for you to explain a decision.

Example: Helping someone to reach a decision

Luke suffered brain damage after a work accident and now gets confused and frustrated about making many decisions. He lives with his sister Marjorie, who the Court of Protection has appointed as his deputy for property and affairs.

Christmas is approaching and Marjorie wants to get Luke involved in buying presents. She first asks Luke in the evening what gifts he might like to buy each relative. However, he has difficulty in telling one relative from another and gets upset.

Marjorie remembers that Luke sometimes seems more alert after breakfast. She asks him about the presents again then. This time Luke can express his views much more clearly about which gifts to buy each family member.

How do I work out the person’s best interests?

The law says you must always act in the person’s best interests. That means you must make decisions for the benefit of the person and not necessarily you or anyone else.

In working out the person’s best interests, bear in mind:

-

their past and present wishes

-

their beliefs and values

-

the views of family members and carers

-

whether they might regain mental capacity and you could hold the decision off until then

Avoid drawing conclusions about the person’s best interests simply on the basis of their age, ethnic background, general appearance, gender or sexuality.

You also must not discriminate against the person – treat them worse – for any of these reasons. Always consider the person’s best interests as an individual.

Example: Considering beliefs and values

Peter is a young man who was studying at college until he was involved in a road accident and suffered a brain injury. He now lacks capacity to make any significant decisions about managing his money. The Court of Protection has appointed his father as his deputy so he can invest the compensation Peter got after the accident.

Peter’s father knows his son had very strong ethical objections to the actions of certain multinational companies. He therefore picks an ethical investment fund. Even though he disagrees with his son’s views, he takes account of them when considering what’s in Peter’s best interests.

For more about best interests, see chapter 5 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

5. What should I do if…? Some common decisions as a property and affairs deputy

There’s more than one deputy

Sometimes the Court of Protection appoints two or more deputies for the same person.

The court will tell you how to make decisions if you’re not the only deputy. It will be either:

-

together (usually called ‘jointly’), which means all the deputies have to agree on decisions

-

separately or together (usually called ‘jointly and severally’), which means deputies can make decisions on their own or with other deputies

Example: Making decisions together

Brett and Lucy have been appointed joint property and affairs deputies for their father, Donald, who has developed Alzheimer’s disease and is moving into a nursing home.

Brett and Lucy have to decide what to do with Donald’s house. Because they’ve been appointed joint deputies, they must agree on each financial decision they make for their father.

Brett thinks it’s in Donald’s best interests to sell the property and invest the money for Donald’s future care. His daughter thinks it’s in Donald’s best interests to keep the property, because he enjoys visiting and spending time in his old home.

After making every effort to get Donald’s views, the family meet to discuss the issues involved. The deputies listen to other family members’ views before agreeing it would be in their father’s best interests to keep the property for as long as he is able to enjoy visiting it.

I want to claim expenses as a deputy or be paid

You can claim reasonable expenses for things directly associated with fulfilling your role as deputy, such as phone calls, postage and any necessary travel costs.

However, you can’t claim travel costs for purely social visits to the person, as these fall outside your duties as a deputy and under your role as a friend or family member.

You also can’t claim for the time you spend carrying out your duties, unless you’re a professional deputy. ‘Lay’ (non-professional) deputies are unpaid.

Deputies can’t use their position to benefit themselves. The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) may ask you to explain your expenses in your deputy report.

If your expenses are considered unreasonable, you may have to repay them. In extreme cases, you may be discharged as a deputy (have your role as a deputy removed by the Court of Protection).

Record your expenses as you go along using the online deputy reporting service.

Example: Claiming expenses as a deputy

Sophia is a property and affairs deputy for her brother Roberto, who suffered brain damage after a severe epileptic fit. Roberto now has difficulty making day-to-day decisions and lives in a care home.

Roberto owns a flat, which Sophia rents out to help pay his care home fees and other costs. She makes occasional visits to her accountant to discuss this and other aspects of her deputyship. Sophia can claim expenses for these visits, including petrol for the trip and parking costs – otherwise she would be left out of pocket for performing her deputy duties.

However, she can’t claim for family trips to visit Roberto in his care home on his birthday and at Christmas. These count as purely social visits and are not part of Sophia’s duties as a deputy.

I want to make a gift from the person’s funds

Property and affairs orders normally let you make only limited gifts on the person’s behalf, and OPG will ask you to explain any gifts in your deputy report. Most court orders say you can make gifts only on customary occasions, such as birthdays or anniversaries.

Before making a gift, also ask yourself:

-

Would the person have wanted to make a gift like this if they still had mental capacity?

-

Is the value of the gift similar to gifts the person previously gave to this person or people in a similar position?

-

Is the gift of the right size for the person’s estate – or is it too valuable, for example?

-

Has the person’s financial situation changed? For example, they may have moved into a nursing home and can no longer afford gifts they once could

Remember, gifts must serve the person’s best interests, not yours – so it would be wrong to use the person’s funds to buy big gifts for your own close family, for example, if the person would never have done so.

Before you make larger gifts of money or property – for instance, as part of planning for inheritance tax – you must apply to the Court of Protection for permission. If you make such a gift without permission, you may have to pay it back.

Find out more about giving gifts on someone’s behalf

I want to pay professionals to help manage the person’s estate

As deputy, you can employ professionals such as accountants and solicitors to help manage the person’s affairs. For example, it would be reasonable to pay accountants to draft the person’s annual tax return if they had a complex investment portfolio.

However, it might not be appropriate to employ a solicitor to do something straightforward like paying the person’s nursing home fees. Professional services you pay for must be in keeping with the task they’re needed for and the person’s funds.

I need to enter into a transaction for the person – am I liable?

If you enter into a transaction with someone on behalf of the person – for example, hiring a workman to repair the person’s house – you won’t be personally liable for payment.

If you enter into a written contract, you need to state that the contract is between the person – represented by you – and the other person or company. When signing any agreement on behalf of the person, sign it in the name of the person ‘acting by’ you, the deputy. For example:

This agreement is between [the person’s name] acting by [your name] and [the other person or company’s name].

I want to sell the person’s house

Unless your court order says directly that you can sell a house or other property the person owns or has a share in, you should apply to the Court of Protection for permission. If you don’t, you risk acting outside your authority as a deputy.

It costs £371 to apply to the court – paid from the person’s funds – and there may be extra costs if there’s a court hearing. You can also apply to pay less or no fee for an application to the court if the person has a low income.

Find out more about what’s involved in selling property.

I want to make a loan from the person’s funds

Loans are rarely allowed under deputy court orders. To make a loan from the person’s funds, you’d need to apply to the Court of Protection.

If a loan is allowed, you’re likely to have to draw up a loan agreement, including interest payments.

The law says you must manage the person’s finances with even more care than your own.

I want to buy things to help the person feel better – not just manage their finances

Managing the person’s finances in their best interests is about more than just paying regular bills. You should also consider spending on things that will maintain or improve the person’s quality of life.

Some examples are:

-

new clothes and hairdressing

-

items for their home or room in the care home

-

paying for extra support so the person can go out more, for example to visit friends or relatives or to go on holiday

As with gifts, your purchases must be in the best interests of the person and in keeping with the value of their assets.

I want to hand over my deputy duties to someone else

Although you can seek advice from others – including experts – about the person’s property and finances, the law says you can’t normally delegate (hand over) your decision-making to someone else.

Someone else can take over your deputy duties only if your court order says they can in certain areas.

Otherwise, you as deputy ultimately have to make the decisions and are responsible for them.

There’s a dispute about my role as a deputy

Sometimes disputes and disagreements occur over the way a deputy handles the person’s property and finances. Disputes can occur between the deputy and the person or with others who have an interest in the person, such as family members.

If you’re open and involve others in decision-making, problems are less likely to occur.

Deputies or others involved in a dispute should first try to come to an agreement between themselves. If that doesn’t work, contact OPG for guidance and advice.

I need to share personal details about the person

Deputies have a ‘duty of confidentiality’ not to reveal details of the person’s affairs unless:

-

the person agreed to it when they had capacity

-

OPG asks for the information

-

there’s another good reason (for example, the person or someone else might come to harm if you didn’t)

You should also still consult others – friends and family of the person, financial or other experts – in carrying out your deputy duties if it’s in the person’s best interests to do so.

Record any sales, purchases and disputes in your online deputy report when they happen – it will make it easier when you submit your report.

6. How am I supervised as a deputy?

The role of the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) is to advise and support deputies and to protect people who lack mental capacity from abuse or exploitation.

OPG tailors its supervision of your deputyship to meet your needs and the person’s.

Supervision includes phone advice from OPG, support from professional visitors and yearly or more frequent deputy reports.

You can call the OPG contact centre on 0300 456 0300 to discuss any of the issues raised in this booklet.

Protecting the person

OPG’s other role is to protect the person you are making decisions for. Abuse of the person is anything that goes against their human and civil rights. It can be deliberate or can happen because a deputy doesn’t know how to act correctly or lacks the right help and support.

Abuse of property and affairs deputyships can include:

-

theft or fraud

-

misuse of property, possessions or benefits

-

putting too much pressure on the person

-

neglect

Court of Protection visitors

OPG sometimes arranges for Court of Protection visitors to meet the person and their deputy(s) to see how a deputyship is going and whether you need more support. On rare occasions, a visitor might also be asked to investigate suspected abuse of the person.

As well as speaking to you and the person, visitors may contact others involved in the deputyship, such as family members or banks.

As a deputy, you must accept a court visitor and give them any information they ask for.

Investigations

If OPG believes you may not be acting in the person’s best interests, we will investigate. Investigations can take some time, depending upon how complicated they are. While an investigation lasts, OPG will work with everyone involved to make sure the person’s best interests are being looked after.

However, if OPG suspects a deputy of theft or fraud, we may report the matter to the police.

Outcomes of an investigation

Following an investigation, OPG may supervise your deputyship more closely and make more regular contact. This is to make sure we’re offering the right level of support and working together in the best interests of the person.

If the investigation finds you’re not acting in the person’s best interests or that you’ve abused your position as a deputy, OPG may apply to the Court of Protection to discharge you (remove you from your deputyship).

If deputies misuse a person’s funds, the court will tell the bond company to ‘call in’ the bond. The bond company will pay some money to the person’s estate immediately so the person doesn’t lose out. It will then seek to recover the money from you.

Safeguarding

‘Safeguarding’ means protecting the person from harm. Contact OPG if you have concerns about the person you’re responsible for:

phone

0300 456 0300

textphone

0115 934 2778

We’ll answer your call Monday to Friday, 9am to 5pm; Wednesday, 10am to 5pm.

Call 999 if someone is in immediate danger or your local police if you think someone has committed a crime.

7. Changing your deputyship

You must apply to the Court of Protection if you have to:

-

change your deputyship, for example to make decisions that aren’t in the original order

-

make a one-off decision on something not covered by the order

-

renew your deputyship (if it has an expiry date)

To apply, you need to fill in an application form (COP1) and a witness statement (COP24) with details of the person’s current finances and why you are applying. You then send the forms to the court with a cheque for the £371 application fee, paid from the person’s funds.

You can apply for help paying the fee if the person gets certain benefits or is on a low income.

Find out more about forms and information about changing your deputyship

8. When does a deputyship end?

Your deputyship ends when one of the following things happens:

-

The person regains mental capacity. If this happens, fill in a COP9 form and send it to the Court of Protection with any supporting evidence, for example a doctor’s letter

-

You decide to step down. To do this, apply to the court with a COP1 form. The court will take steps to appoint a new deputy

-

The person dies. Please tell OPG, and we will explain what to do next. You’ll need to provide evidence, such as a death certificate

-

The deputy dies (if it is a sole or joint deputyship). Your solicitor or executor should tell OPG, and a new deputy will need to be appointed

Find out more about forms and other supporting information to end your deputyship. Or call OPG on 0300 456 0300 or the Court of Protection on 0300 456 4600.

9. Deputy checklist

You might want to print off this checklist and keep it somewhere prominent to remind you of your tasks as a deputy.

-

I’ve arranged my Court of Protection bond

-

I understand the terms of my court order and it has no mistakes (if it has mistakes, I’ve told the Court of Protection)

-

I’ve let the right organisations and individuals – banks, the person’s solicitor – know that I’m the person’s deputy

-

I’ve set up a separate deputyship account or accounts (if appropriate)

-

I understand what I should and shouldn’t spend the person’s money on as a deputy

-

I’ve registered for the online deputy reporting service and have started recording my decisions and transactions and keeping receipts

-

I understand what mental capacity means and how to make decisions in the person’s best interests

-

I know about the fees – for deputy assessment and supervision – I need to pay to OPG

-

I know I need to submit a deputy report to OPG when asked showing how I’ve looked after the person’s property and finances

10. Jargon buster

Abuse

Abuse is when someone violates someone else’s human or civil rights. Abuse may be a single act or repeated acts. It can also be neglect or a failure to act. For a property and affairs deputyship, abuse may occur when someone persuades a vulnerable person to enter into a financial transaction that they haven’t, or cannot, agree to.

Best interests

Deputies should always consider what action is in the person’s best interests when making a decision. You should also consider the person’s past and present wishes and think about consulting others. For more on best interests, see the section in this guide ‘How do I work out the person’s best interests?’.

Client

A term sometimes used for the person without mental capacity whose property and affairs decisions the Court of Protection has appointed you to make.

Code of Practice

A guide to the Mental Capacity Act that you can order or download. The code contains much valuable information for attorneys.

Court of Protection visitor

Someone who is appointed to report to the Court of Protection or the Office of the Public Guardian on how deputies are carrying out their duties.

Dementia

Term used for different illnesses that affect the brain and lessen the ability to do everyday tasks. ‘Dementia’ describes symptoms, not the condition itself. Symptoms include:

-

loss of memory

-

difficulty in understanding people and finding the right words

-

difficulty in completing simple tasks and solving minor problems

-

mood changes and emotional upsets

Deputy

Someone appointed by the Court of Protection to make decisions on behalf of another person who lacks mental capacity to make those decisions themself. A deputy may be appointed to make decisions about property and financial affairs, or health and welfare, or both.

Deputies may be lay, such as family members or friends of the person lacking capacity. Or they may be professional, such as solicitors, accountants or local authority employees.

Exemptions and remissions

If the person has a low income, the deputy can apply on their behalf for an exemption (paying no fee) or remission (paying a lower fee) of OPG’s assessment and supervision fees.

Least restrictive care

If a person lacks mental capacity, decisions taken on their behalf must respect the person’s freedom of action and must be the least restrictive option. This means keeping the person safe while limiting their rights and freedoms as little as possible.

Mental capacity

The ability to make a decision about something at the time the decision needs to be made. The legal definition of someone who lacks mental capacity is set out in section 2 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. For more on mental capacity, see the section in this guide ‘What does mental capacity mean?’.

Mental Capacity Act 2005

The act is designed to protect people who can’t make decisions for themselves. This could be due to a mental health condition, a severe learning disability, a brain injury or a stroke. The act’s purpose is to allow adults to make as many decisions as they can for themselves and for a deputy or others to make decisions on their behalf.

Office of the Public Guardian

A part of the Ministry of Justice that protects people in England and Wales who may not have the capacity to make certain decisions for themselves, such as about their finances or health.

Property and affairs

Any possessions owned by a person (such as a house or flat, jewellery or other possessions), the money they have in income, savings or investments or any expenditure.

Wilful neglect

A failure to carry out care by someone who has responsibility for a person who lacks mental capacity to care for themselves. This is an offence under the Mental Capacity Act.