SD4 How to be a health and welfare deputy (web version)

Updated 21 March 2023

Applies to England and Wales

1. Getting started

This guide is for deputies appointed by the Court of Protection to make health and welfare decisions for people who don’t have mental capacity to make such decisions themselves.

Being a deputy is an important responsibility. The court order sent to you by the Court of Protection says who you are authorised to make decisions for and in exactly which areas.

Please make sure you read and fully understand the court order. If there’s anything you don’t understand, contact the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG).

If this is all new to you and feels a bit daunting, don’t worry, you’re not alone. If you need help making a decision, discuss it with your case manager at OPG or the care worker or family member of the person you’re making decisions for.

In this guide we use other deputies’ stories to show some things to consider when making decisions. These aren’t final answers but may give you ideas about how to act.

An A-Z jargon buster at the end of this booklet explains terms you might not understand.

Throughout this guide, we refer to ‘the person’ whose property and finance decisions you are making. Elsewhere, you’ll sometimes seem them called – more officially – ‘the client’

2. What does OPG do?

OPG is a part of the government that supports you in your role as a deputy and makes sure you’re acting in the person’s best interests.

You’ll have two early stages of contact with OPG:

-

A letter we send you once you’re appointed as a deputy, suggesting a time for our introductory ‘settling in’ call about the deputy role.

-

The settling-in call itself, lasting up to an hour, when your case manager will discuss such things as:

-

the terms of your court order

-

the person’s health and care needs

-

how to make decisions as a deputy

OPG has lots of useful information about being a deputy but it can’t give medical or legal advice – for that, speak to an appropriate medical professional or a solicitor.

PO Box 16185

Birmingham B2 2WH

Phone: 0300 456 0300

Email: [email protected]

Monday to Friday 9am to 5pm; Wednesday 10am to 5pm

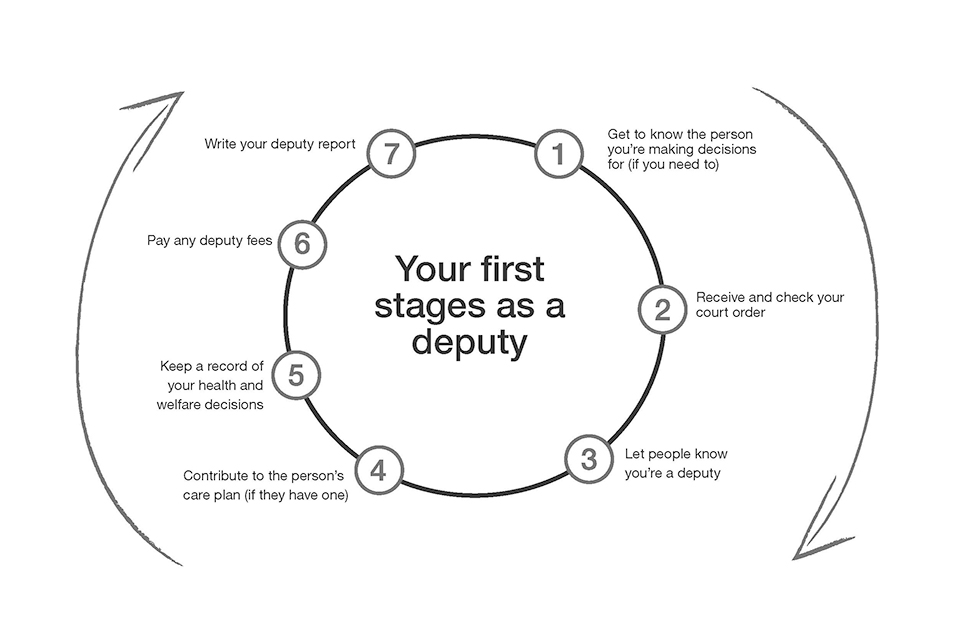

3. Your first stages as a deputy

1. Get to know the person you’re making decisions for

If you didn’t already know the person you’re acting for as a personal welfare deputy, you should start getting to know them now. The main rule in making health and welfare decisions for the person is that those decisions must always be in their best interests.

If the person once had mental capacity but doesn’t now, think about the kinds of decisions they used to make – about the food and clothes they liked, about the surroundings in their home or about leisure or social activities, for example.

If the person sometimes has mental capacity and sometimes doesn’t (‘fluctuating capacity’), make a note of the sorts of decisions they make when they do have mental capacity.

Ask other people, such as close friends and relatives, about the person’s likes and dislikes, wishes and beliefs and past decision-making if they once had mental capacity. Use all these sources of information to guide your decision-making as the person’s deputy.

2. Receive and check your court order

Court orders are different for each deputyship. When the Court of Protection sends your order, make sure you’re familiar with the exact kinds of decisions it says you can make for the person.

Common kinds of decisions that health and welfare orders cover are:

-

where the person lives

-

who they live with

-

their day-to-day care, including diet and dress

-

consenting to medical and dental treatment for the person

-

the person’s care arrangements

-

leisure or social activities they should take part in

-

complaints about the person’s care or treatment

Read through your court order carefully to check for errors such as names spelled wrongly. If there are any, contact the Court of Protection immediately to have them fixed.

For more serious errors, you’ll need to complete a COP9 form. Send it to the court within 21 days of the date the order was sent to you.

If you haven’t told the court about errors within 21 days, you may get charged for another application to correct the problem.

You can only make decisions for the person in areas that the Court of Protection has authorised. If you want to make other decisions, you need to apply to the court to change your deputy order.

3. Let people know you’re a deputy

You need to let certain people and organisations the person is involved with know that you’re the deputy. This is called ‘registering’ the deputyship. Some examples are:

-

health professionals such as doctors and nurses

-

social workers

-

care providers

-

education providers

If you need to send your deputy order somewhere when registering your deputyship, ask for it to be returned or you may run out of copies. You can get more copies, costing £5 each, from the Court of Protection.

4. Contribute to the person’s care plan (if they have one)

A care plan is an agreement between the person – helped by you – and health or social services outlining the person’s needs and the support and care they should get. Most, but not all, people with health and welfare deputyships have a care plan. Care plans can be brief or very detailed, depending on the person’s circumstances.

You and the person should be involved when the plan is being written. If the person doesn’t have the mental capacity to agree to the care plan, it’s up to you to sign it on their behalf.

As a deputy, you can:

-

discuss the plan and suggest any changes

-

ask for your comments, based on your knowledge of the person, to be included in the care plan

-

ask for a copy of the care plan – it may help you to make decisions for the person

But you shouldn’t:

-

change the care plan – you don’t have the authority

-

repeatedly ask care staff for copies of documents such as daily record sheets, logs and risk assessments – make sure that your demands are reasonable and give staff time to respond

If you have concerns about the care plan, discuss them with a care home manager, a social worker or a doctor.

Example: Working with a care plan*

Margaret is a young woman with severe mental health problems. Her mother, Sheila, is her deputy and helps to make many of the health and welfare decisions Margaret can’t make herself.

A team of doctors, care staff and social workers has prepared a care plan to help Margaret’s carers act in her best interests.

The care plan covers the medication Margaret has been prescribed, help with her personal care and other activities including art therapy.

The team tried their best to involve Margaret in planning her care but her doctor has assessed her and stated she lacks capacity to agree to many aspects of her care plan. As her deputy, her mother can agree or disagree to those parts of the plan that Margaret can’t.

———

* The examples in this guide use imaginary characters and situations to help you to make decisions as a deputy

5. Keep a record of your decisions for the person

It’s part of your duty as a deputy to keep a record of the important health and welfare decisions you make on the person’s behalf. You need to include these records when you submit your deputy report.

Begin keeping a written record as soon as you can of decisions you make about the person’s care.

Decisions might include:

-

moving the person into a care home to live

-

a change to the person’s diet, discussed with care home staff

-

consenting to medical treatment for the person, such as a scan or operation

-

agreeing to a new leisure activity – say, country walks or a dance night

If you consulted other people about a health and welfare decision, make a note of that, too.

You don’t need to record every day-to-day decision you make, such as meals you prepared for the person on a particular day or every outing you choose for the person. If in doubt about whether to record a decision, include it just in case.

6. Pay any deputy fees

You pay OPG’s fees for supervising your deputyship from the person’s funds, not your own. The fees include:

-

a one-off deputy assessment fee of £100

-

a yearly supervision fee of £320

If the person has a low income, you can apply for an ‘exemption’ (paying no fee) or ‘remission’ (paying a lower fee) of the assessment and supervision fees.

Assessment fee

This one-off fee is for assessing the circumstances of each deputyship. OPG asks for payment of the fee early on in your deputyship. You can reclaim the fee from the person’s funds if you paid it yourself.

Supervision fee

There is also a yearly fee to cover the cost of supervising your deputyship. Supervision fees are billed towards the end of the financial year, in April. In your first year, you only have to pay for the proportion of the year you’ve been deputy.

Find out more about fee exemptions and remissions, along with an application form to pay less.

7. Write your deputy report

As your court order states, deputies need to complete a report at the end of every year of their deputyship. Sometimes OPG will ask you to report more often.

OPG uses the report to work out how much support you might need as a deputy and to make sure you are acting in the person’s best interests. Your report should include:

-

significant health and welfare decisions you made for the person throughout the year – for example, arranging flu jabs or major dental work

-

how you involved the person (if possible) in decision-making

-

who else you consulted about making decisions

OPG will send you a report form to ll in before it’s due. If you don’t send your report when OPG asks for it, or if OPG has other concerns about it, we will review your deputyship.

Ultimately this could lead to us applying to the Court of Protection to remove you as a deputy and appoint another deputy instead.

If you’re also the person’s deputy for property and financial decisions, you can now submit that report online. Personal welfare deputies will soon also be able to report online – we’ll let you know when.

The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 Code of Practice has lots more detail and examples about how deputies can act.

You can order or download a copy

4. Your role as a deputy

What does mental capacity mean?

‘Mental capacity’ means the ability to make a specific decision at the time it needs to be made. A person with mental capacity has at least a general understanding of:

-

the decision they need to make

-

why they need to make it

-

any information relevant to the decision

-

the likely consequences of the decision

They should be able to tell other people about their decision through speech, gestures or other ways such as voice-activated equipment.

People can sometimes make certain kinds of decisions but don’t have the mental capacity to make others. For example, someone may be able to decide what they’d like for dinner but be unable to understand whether they should have a particular medical treatment.

Mental Capacity: five principles

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 – which governs what deputies can do – sets out five rules about mental capacity. The rules affect you as a deputy in these ways:

-

The person should make decisions for themself unless you can show that they’re unable to make them.

-

You need to give the person all the help they need to make a decision before deciding they can’t make that decision.

-

If the person makes what seems to be an unwise or odd decision, that doesn’t mean they lack capacity to make it. (Many people make unwise decisions from time to time.)

-

Any decision you make for the person must be in their best interests – a very important point explained more below.

-

Anything you do on behalf of a person who lacks capacity should restrict their basic rights as little as possible.

How can I help the person make a decision for themselves?

People may have mental capacity some of the time but not all of the time. If the person is usually liveliest in the evening, for example, that may be the best time to involve them in decision-making.

The person may also be more responsive if you choose the right setting to ask about decisions – perhaps at home, rather than in an unfamiliar environment.

You could also use other ways to communicate. Try using pictures or sign language to explain a decision, for example.

Sometimes the person may just need more time for you to explain a decision.

Example: Helping someone to reach a decision

Michael suffered severe brain damage after a work accident and now gets confused and frustrated about making many decisions. He lives with his sister Sally, who the Court of Protection has appointed as his personal welfare deputy.

Before he had his accident, Michael used to be interested in fashion and has a large collection of clothes. Sally thinks it would be good for Michael to help decide what he should wear each day – she thinks it might make him feel better. However, when she asks him about this in the morning as he is getting dressed, he finds the choices confusing and gets upset.

Sally remembers that Michael sometimes seems more alert and capable later in the day. She tries asking him in the evening what clothes he would like to wear the next day. Now Michael can express much more clearly what he would like to wear.

How do I work out the person’s best interests?

The law says you must always act in the person’s best interests. That means you must make decisions for the benefit of the person and not necessarily you or anyone else.

In working out the person’s best interests, bear in mind:

-

their past and present wishes

-

their beliefs and values

-

the views of family members and carers

-

whether they might regain mental capacity and you could hold the decision off until then

Best interests meetings

If a decision is within your area of responsibility, and it’s complicated or on a topic you don’t know much about, you can call a ‘best interests meeting’.

As part of these meetings, a group of people involved in the care of the person gather to share views on the best course of action. This process may help you make a decision in the person’s best interests.

Other decision-makers

You don’t decide everything for the person – you can only make decisions in areas the court order says you can.

The law gives other people decision-making power for the person, too. For example, a doctor may need to decide whether a treatment is in the person’s best interests or a relative may make day-to-day care decisions.

For decisions that don’t fall to you, the decision-maker may consult you. If you disagree with a doctor’s decision, for example, you can ask the Court of Protection to consider it.

Avoid drawing conclusions about the ’s best interests simply on the basis of their age, ethnic background, general appearance, gender or sexuality.

You also must not discriminate against the person – treat them worse – for any of these reasons. Always consider the ’s best interests as an individual.

For more about best interests, see chapter 5 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

Decisions no one can make for the person

There are some very personal decisions that no one can make for the person. You can’t:

-

stop treatment aimed at keeping the person alive (‘life-sustaining treatment’)

-

decide who the person marries or divorces

-

prevent the person from having contact with people

-

decide who the person votes for in a public election

5. What should I do if…? Some common decisions as a personal welfare deputy

There’s more than one deputy

Sometimes the Court of Protection appoints two or more deputies for the same person.

The court will tell you how to make decisions if you’re not the only deputy. It will be either:

-

together (usually called ‘jointly’), which means all the deputies have to agree on decisions

-

separately or together (usually called ‘jointly and severally’), which means deputies can make decisions on their own or with other deputies

I need to decide where the person lives

Your court order may state that you, as deputy, can decide where the person lives. You should decide this by working with family, friends and other care providers.

You should:

-

research accommodation that is right for the person, if they pay for their own care

-

if the person doesn’t pay for their care, work closely with the local authority to make sure their accommodation best suits their needs; if there’s a problem, discuss it with social services and care staff

-

sign the necessary documents on behalf of the person

But you shouldn’t:

- move the person to a different place without consulting others such as family members, health professionals, care staff and social services

If there’s a disagreement, a best interests meeting may help to resolve it. If that doesn’t help, you may need to ask the Court of Protection to decide.

Example: Making decisions together about living arrangements

Stephanie and Simon have been appointed joint personal welfare deputies for their brother, Anthony, who has severe learning difficulties. Anthony used to live with his parents, but they have died.

One of Stephanie and Simon’s rst tasks is to decide where Anthony should live. Because they’ve been appointed joint deputies, they must agree on every health and welfare decision they make for their brother.

Simon thinks Anthony’s difficulties with caring for himself are serious enough that he should move into a care home. Stephanie says living with strangers might make Anthony distressed and thinks he’d be better off living with Simon or her – if they could manage it.

After making every effort to get Anthony’s view, the family meet to discuss the issues involved. The deputies listen to other family members before agreeing it would be in Anthony’s best interests to move into a care home, where he can get the care he needs.

The family agree to visit Anthony often in his new home.

I need to work regularly with care providers

Care providers who are likely to have regular contact with you and the person include:

-

support workers

-

residential workers

-

home helps

-

personal assistants

-

nursing staff

Registered care providers have a duty to provide care for the person, following the care plan.

The person may already be in residential care when the court order begins. If so, care home professionals will already have responsibility for the person’s day-to-day care.

You should:

-

tell staff about the person’s past and recent wishes about their care to help them to tailor their support

-

if possible, involve the person in discussions about their own care

-

raise any questions or concerns you have about the care plan promptly; don’t let them fester

But you shouldn’t:

- tell staff to carry out care that’s not been agreed. Care plans can be changed – but this must be agreed by all the relevant people

Example: Working with care providers

Emily is an elderly woman with Alzheimer’s disease who lives in a residential care home. Her brother, Bert, is her personal welfare deputy.

Emily suffers a minor injury when wandering about the home in the early hours of the morning. Bert is worried about this happening again. He asks a nurse if Emily can be supervised more closely.

The nurse says they can install motion sensors and door alarms in Emily’s room to alert staff if she wanders at night. That way, she wouldn’t be locked in but staff would be able to act if she left her room.

Emily, Bert, the care home manager and Emily’s doctor discuss which way of responding will restrict Emily’s freedoms and rights the least. They weigh up the advantages and disadvantages and agree that sensors and alarms are in Emily’s best interests.

Creating a story book

One way to help care providers look after the person in a more personal way is to prepare a ‘life story book’ with photos and information about the person’s background. It can include:

-

jobs they’ve had and achievements

-

their likes and dislikes

-

their favourite food and music

-

important people in their life

I need to make decisions about the person’s diet and dress

Decisions about day-to-day care should support the person and not be used as a way of controlling their behaviour, even if it’s dif cult. Remember that the Court of Protection gave you these powers to respect the person’s preferences.

You should:

-

talk to the person about their food and clothing preferences (if possible)

-

tell staff or care providers about the person’s preferences and any religious requirements about diet and dress

-

buy brands of clothing that the person liked and discuss this in care planning or review meetings; if there’s a problem with the clothes care home staff are dressing the person in, discuss this with the staff and manager

But you shouldn’t:

-

take the person to their room and change their clothing on each visit

-

with hold food or drink given to the person by care providers without consultation

Example: Making decisions about diet

Jakub has dementia and lives in a nursing home. Before losing capacity, he never ate puddings after a meal. However, he has noticed other people in the care home enjoying puddings and tells staff he wishes to start eating puddings.

Jakub’s son Karol is his personal welfare deputy. Karol is worried about his father putting on weight, because he has a heart condition. Karol asks the nursing home manager to stop giving his father puddings.

The manager suggests a meeting with Jakub and Jakub’s GP. The four of them sit down and agree that Jakub can be offered fruit and a small pudding at the end of the dinner. This means that Jakub can enjoy his food without making his heart condition worse.

I need to make decisions about the person’s leisure and social activities

When making such decisions, think about the person’s past preferences and how they respond now during activities.

You should:

-

if possible, include the person in discussions about leisure activities and outings they’d like

-

arrange activities that the person used to do, such as a trip to the theatre, cinema, zoo, bingo, park or a concert

-

let care home staff know if there are things the person disliked doing

But you shouldn’t:

-

exclude the person from discussions about their leisure and social activities, even if it’s difficult to involve them

-

prevent them from taking part in leisure or social activities they’d enjoy

Example: Deciding on social activities

Isabella, a young woman with severe learning difficulties, lives at home with her parents – who are her deputies – and attends an activity centre several days a week.

The centre staff would like to take some of the people who attend on an excursion. They speak to Isabella’s parents.

Her parents think an excursion would be good for her. However, they are worried because Isabella can get frightened if she is surrounded by strangers.

The staff try to involve Isabella in the decision but she doesn’t respond. Isabella’s parents and the staff then meet and agree that an excursion is in her best interests, as long as a support worker goes with her to help if she becomes too anxious.

I’m asked to agree to medical treatment for the person

Your decisions about the person’s treatment must be in line with the court order, in the person’s best interests and must restrict them as little as possible.

You should:

-

sign ‘consent to treatment’ forms on behalf of the person – taking into account their past wishes

-

share any preferences that the person has said or written down with care staff

-

make sure the staff have copies of any advance decision to refuse treatment (sometimes also called an ‘advance directive’ or ‘living will’) or any written statement of wishes and preferences, such as an advance statement

-

follow the person’s wishes, even if you disagree with them

But you shouldn’t:

-

impose your own medical choices – you must make decisions based on the person’s past preferences and best interests

-

treat the person yourself or change prescribed medication or treatment – you must agree upon changes with health care staff

-

if the person is in a care home, change incontinence pads, give medication or change dressings without asking the manager

Remember: the key to acting in the best interests of the person is to work together with everyone involved in their care.

Example: Deciding about treatment

Peter has severe learning disabilities and can’t communicate well. His parents are his health and welfare deputies.

Peter cuts his leg while outdoors; there’s dirt in the wound. A doctor wants to give him a tetanus jab but Peter seems scared of the needle and struggles against it.

The doctor discusses Peter’s ability to make and understand decisions with his parents. They believe that he doesn’t understand the risk to his health, though they have tried to explain. Peter is unable to make the decision.

The doctor decides that it is in Peter’s best interests to give the vaccination. She asks a nurse to comfort Peter and, if necessary, restrain him by holding his hands, while she gives the injection.

I need to share personal details about the person

Deputies have a ‘duty of confidentiality’ not to reveal details of the person’s affairs unless:

-

the person agreed to it when they had capacity

-

OPG asks for the information

-

there’s another good reason (for example, the person or someone else might come to harm if you didn’t)

You should also still consult others – friends and family of the person, medical or other experts – in carrying out your deputy duties if it’s in the person’s best interests to do so.

I want to hand over my deputy duties to someone else

Although you can seek advice from others, such as doctors and care staff, about the person’s health and care, the law says deputies can’t normally delegate (hand over) decision-making to someone else.

Someone else can take over your deputy duties only if your court order says they can in certain areas.

Otherwise, you as deputy ultimately have to make the decisions and are responsible for them.

I want to claim expenses as a deputy or be paid

Health and welfare deputies can claim reasonable expenses for things directly associated with fulfilling your role as deputy, such as phone calls, postage and any necessary travel costs.

You can’t claim travel costs for purely social visits to the person, as these fall outside your duties as a deputy and under your role as a friend or family member.

You also can’t claim for the time you spend carrying out your duties, unless you’re a professional deputy. ‘Lay’ (non-professional) deputies are unpaid.

You need to claim expenses from whoever is in charge of the person’s money. They may be a deputy for nancial decisions, appointed separately by the Court of Protection, or someone else.

Keep receipts and bank statements as a record of your spending.

Deputies can’t use their position to benefit themselves. The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) may ask you to explain your expenses in your deputy report.

If your expenses are considered unreasonable, you may have to repay them. In extreme cases, you may be discharged as a deputy (have your role as a deputy removed by the Court of Protection).

There’s a dispute about my role as a deputy

Sometimes disputes and disagreements occur over a deputy’s health and welfare decisions. Disputes can occur between the deputy and the person or with others who have an interest in the person, such as family members.

If you’re open and involve others in decision-making, problems are less likely to occur.

Deputies or others involved in a dispute should first try to come to an agreement between themselves.

If that doesn’t work, contact OPG for advice.

You need to record any disputes, and details of how they were resolved, in your deputy report.

6. How am I supervised as a deputy?

The role of the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) is to advise and support deputies and to protect people who lack mental capacity from abuse or exploitation.

OPG tailors its supervision of your deputyship to meet your needs and the person’s. Supervision includes phone advice from OPG, support from professional visitors and yearly or more frequent deputy reports.

You can call the OPG contact centre on 0300 456 0300 to discuss any of the issues raised in this booklet

Protecting the person

OPG’s other role is to protect the person you are making decisions for. Abuse of the person is anything that goes against their human and civil rights. It can be deliberate or can happen because a deputy doesn’t know how to act correctly or lacks the right help and support.

Abuse of health and welfare deputyships can include:

-

violence, such as pushing or slapping the person

-

involving the person in sexual acts without their consent

-

threatening the person

-

imposing your own beliefs on the person

-

punishing the person because they’ve been ‘bad’

-

stopping the person contacting other people

-

neglecting the person, such as not providing medicine or food

Court of Protection visitors

OPG sometimes arranges for Court of Protection visitors to meet the person and their deputy(s) to see how a deputyship is going and whether you need more support. On rare occasions, a visitor might also be asked to investigate suspected abuse of the person.

As well as speaking to you and the person, visitors may contact others involved in the deputyship, such as family members or medical staff.

As a deputy, you must accept a court visitor and give them any information they ask for.

Investigations

If OPG believes you may not be acting in the person’s best interests, we will investigate. Investigations can take some time, depending upon how complicated they are. While an investigation lasts, OPG will work with everyone involved to make sure the person’s best interests are being looked after.

However, if OPG suspects a deputy of theft or fraud, we may report the matter to the police.

Outcomes of an investigation

Following an investigation, OPG may supervise your deputyship more closely and make more regular contact. This is to make sure we’re offering the right level of support and working together in the best interests of the person.

If the investigation finds you’re not acting in the person’s best interests or that you’ve abused your position as a deputy, OPG may apply to the Court of Protection to discharge you (remove you from your deputyship).

Safeguarding

‘Safeguarding’ means protecting the person from harm. Contact OPG if you have concerns about the person you’re responsible for:

phone

0300 456 0300

textphone

0115 934 2778

We’ll answer your call Monday to Friday, 9am to 5pm; Wednesday, 10am to 5pm.

Call 999 if someone is in immediate danger or your local police if you think someone has committed a crime.

7. Changing your deputyship

You must apply to the Court of Protection if you have to:

-

change your deputyship, for example to make decisions that aren’t in the original order

-

make a one-off decision on something not covered by the order

-

renew your deputyship (if it has an expiry date)

To apply, you need to fill in an application form (COP1) and a witness statement (COP24) with details of the person’s current finances and why you are applying. You then send the forms to the court with a cheque for the £371 application fee, paid from the person’s funds.

You can apply for help paying the fee if the person gets certain benefits or is on a low income.

Find out more about forms and information about changing your deputyship

8. When does a deputyship end?

Your deputyship ends when one of the following things happens:

-

The person regains mental capacity. If this happens, fill in a COP9 form and send it to the Court of Protection with any supporting evidence, for example a doctor’s letter

-

You decide to step down. To do this, apply to the court with a COP1 form. The court will take steps to appoint a new deputy

-

The person dies. Please tell OPG, and we will explain what to do next. You’ll need to provide evidence, such as a death certificate

-

The deputy dies (if it is a sole or joint deputyship). Your solicitor or executor should tell OPG, and a new deputy will need to be appointed

Find out more about forms and other supporting information to end your deputyship. Or call OPG on 0300 456 0300 or the Court of Protection on 0300 456 4600.

9. Deputy checklist

You might want to print off this checklist and keep it somewhere prominent to remind you of your tasks as a deputy.

-

I’ve got to know the person, including speaking to their friends and family if necessary

-

I understand the terms of my court order and it has no mistakes. (If it has mistakes, I’ve told the Court of Protection)

-

I’ve let the right individuals and organisations – such as doctors, social workers and care staff – know that I’m the deputy

-

I’m keeping a record of my health and welfare decisions as a deputy

-

I understand how to work with professional care providers

-

I understand what mental capacity means and how to make decisions in the person’s best interests

-

I know about the fees – for deputy assessment and supervision – I need to pay to OPG

-

I know that I need to submit a report to OPG when asked showing the health and welfare decisions I’ve made as a deputy

10. Jargon buster

Abuse

Abuse is when someone violates someone else’s human or civil rights. Abuse may consist of a single act or repeated acts. It can also be neglect or a failure to act.

Best interests

Deputies should always consider what action is in the person’s best interests when making a decision. You should also consider the person’s past and present wishes and think about consulting others. For more on best interests, see the section in this guide ‘How do I work out the person’s best interests?’.

Care home

A home registered with the Care Quality Commission, or Care and Social Services Inspectorate in Wales, that provides accommodation with personal care such as help with washing and dressing. A care home with nursing – also called a ‘nursing home’ – provides both nursing and personal care.

Care plan

A written agreement setting out how to provide care for the person you are making decisions for.

Care worker

Paid workers who support people with everyday tasks who may be elderly or ill, have physical or learning disabilities or emotional or social problems.

Client

A term sometimes used for the person without mental capacity whose property and affairs decisions the Court of Protection has appointed you to make.

Code of Practice

A guide to the Mental Capacity Act that you can order or download. The code contains much valuable information for attorneys.

Court of Protection visitor

Someone who is appointed to report to the Court of Protection or the Office of the Public Guardian on how deputies are carrying out their duties.

Dementia

Term used for different illnesses that affect the brain and lessen the ability to do everyday tasks. ‘Dementia’ describes symptoms, not the condition itself. Symptoms include:

-

loss of memory

-

difficulty in understanding people and nding the right words

-

difficulty in completing simple tasks and solving minor problems

-

mood changes and emotional upsets

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

Safeguards to prevent people without mental capacity from being unnecessarily restricted when in hospital, a care home or a supported living arrangement.

Deputy

Someone appointed by the Court of Protection to make decisions on behalf of another person who lacks mental capacity to make those decisions themself. A deputy may be appointed to make decisions about property and financial affairs, or health and welfare, or both.

Deputies may be lay, such as family members or friends of the person lacking capacity. Or they may be professional, such as solicitors, accountants or local authority employees.

Domiciliary care

Care at home that helps people cope with disability or illness and allows them to maintain independence.

Exemptions and remissions

If the person has a low income, the deputy can apply on their behalf for an exemption (paying no fee) or remission (paying a lower fee) of OPG’s assessment and supervision fees.

Least restrictive care

If a person lacks mental capacity, decisions taken on their behalf must respect the person’s freedom of action and must be the least restrictive option. This means keeping the person safe while limiting their rights and freedoms as little as possible.

Mental capacity

The ability to make a decision about something at the time the decision needs to be made. The legal definition of someone who lacks mental capacity is set out in section 2 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. For more on mental capacity, see the section in this guide ‘What does mental capacity mean?’.

Mental Capacity Act 2005

The act is designed to protect people who can’t make decisions for themselves. This could be due to a mental health condition, a severe learning disability, a brain injury or a stroke. The act’s purpose is to allow adults to make as many decisions as they can for themselves and for a deputy or others to make decisions on their behalf.

Nursing home

A care home that provides nursing care (with, generally, at least one registered nurse on duty). Also called a ‘care home with nursing’.

Office of the Public Guardian

A part of the Ministry of Justice that protects people in England and Wales who may not have the capacity to make certain decisions for themselves, such as about their finances or health.

Protection plan

Agencies, including social services, draw up a plan to safeguard a person without mental capacity who they believe is at risk of harm.

Safeguarding adults board

Each local authority must have a safeguarding adults board. Safeguarding boards review cases where it’s suspected that someone is being abused or neglected.

Wilful neglect

A failure to carry out care by someone who has responsibility for a person who lacks mental capacity to care for themselves. This is an offence under the Mental Capacity Act.