Employment advisers in improving access to psychological therapies: client research

Updated 5 May 2022

DWP research report no. 1013

A report of research carried out by IFF and Bryson Purdon Social Research LLP on behalf of the Work and Health Unit.

Crown copyright 2022.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: [email protected]

This document/publication is also available on our GOV.UK website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: [email protected]

First published April 2022.

ISBN 978-1-78659-402-0

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report forms part of an evaluation of the Work and Health Unit (WHU) programme to increase the number and integration of Employment Advisers (EAs) in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services. EA support is intended to help clients struggling with staying in, returning to, or finding work. The primary aim of the evaluation is to robustly determine the additional employment and health outcomes associated with EA support, within an integrated care setting. This report presents findings from the impact strand of the evaluation, drawing on evidence from a longitudinal telephone survey with IAPT clients in areas where EA support had been introduced or increased, five months and twelve months after entering the IAPT service. A further telephone survey was conducted with IAPT clients in areas where EA support had not yet been introduced or increased, twelve months after entering the IAPT service. Statistical matching was used to create a comparison group from the areas where support had not been introduced or increased, to estimate the impact of EA support. This analysis was supported by longitudinal qualitative interviews with clients from eight case study IAPT services that experienced increased EA support, around five months and twelve months after entering the service.

The research found that:

- On entry to the EA service, clients were more likely to be in employment than looking for work and hence – to a large extent – EA support entailed helping them make an existing job work better for them. This included having difficult conversations with employers, such as requesting reasonable adjustments.

- From a client perspective, EA support was well integrated with therapy and delivered effectively. Clients particularly valued the balance between practical, emotional and motivational support.

- Impact estimates suggest that EA support had a positive impact on employment for clients who were out of work on entry to IAPT, and indicative evidence of a positive impact on job search activities. However, there was also some evidence of EA support being linked to lower levels of confidence in finding work amongst those who remained out of work.

- Impact estimates found no positive impact on return to work among those who were off work sick at IAPT entry.

- Longitudinal survey analysis identified indicative positive outcomes for clients who were working on entry to IAPT, in terms of job retention, reduced presenteeism and improved work relationships. However, it was not possible to make impact estimates for this group due to difficulties in establishing a suitable matched comparison group.

Acknowledgements

This report was commissioned by the Work and Health Unit (WHU), a joint unit for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC).

We would like to thank Lyndon Clews, Laura Parkhouse, David Johnson, Owen Davis, Navneet Dalton and Mark Langdon in WHU’s Employment Advisers in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (EA in IAPT) Evaluation Team for their guidance and contributions throughout the project, and to Chris Sutton and Anna Saunders who designed the evaluation. We would also like to thank Kevin Jarman and his delivery team for their input and support when liaising with IAPT providers, and to the members of the IAPT Outcomes and Informatics group for their advice and expertise.

We would like to thank all IAPT providers involved in the evaluation for the time taken to introduce the evaluation to their clients, and thus providing a crucial gateway to invite services users to take part.

We would also like to thank all the participants that gave up their time to take part in the study. Without them, of course, the research would not have been possible.

Authors and researchers

A large team of research partners worked on the study and contributed to the report.

IFF Research, were the lead contractors and led on all quantitative fieldwork and some qualitative interviews with EAs in IAPT clients. Lorna Adams and Rowan Foster, Directors, headed up the IFF team responsible for the research. Gill Stewart, Associate Director and Christabel Downing, Senior Research Manager, were responsible for day-to-day management of the study. Ed Castell, Senior Research Executive, Johanna Lea, Senior Research Executive, Nicky Mitchell, Research Executive and Rachel Keeble, Research Executive worked on the fieldwork, delivery, analysis and reporting.

ICF led on all qualitative fieldwork and analysis with clients. Lucy Loveless, (Managing Consultant) led the ICF team, and managed all aspects of the qualitative research strand. Hayley D’Souza (Research Consultant) carried out client interviews, worked on data analysis, and authored the qualitative findings sections of this report. Jennifer Uddin (Research Consultant) carried out client interviews and worked on data analysis. Aisha Ahmad (Senior Consultant) carried out client interviews.

Caroline Bryson and Susan Purdon of Bryson Purdon Social Research (BPSR) lead on the impact analysis for this report.

Scott Weich from the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) at Sheffield University led the literature review which underpinned the study and provided academic guidance throughout.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Access to Work | A publicly funded employment support programme that provides personalised support to those who are disabled or have a physical or mental health condition to start or stay in work. |

| Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) | Non-departmental public body designed to improve organisations and working life through the promotion and facilitation of strong industrial relations practice. |

| Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) | NHS organisations in England responsible for the planning and commissioning of health care services for their local areas. |

| Clinical Lead | Clinician taking lead responsibility for the clinical aspects of a IAPT service and who bears the responsibility for clinical governance and ensuring high standards of clinical care and service delivery. |

| Constructed counterfactual | A matched comparison group constructed using the available data on baseline characteristics (for example, age, gender, level of qualifications, among others). This gives a matched comparison that is very similar to the treated group on all selected characteristics. |

| Employability partners | Refers here to stakeholders from organisations delivering employment support and advice who work collaboratively with Employment Advisers in IAPT services. |

| Employment Adviser (EA) | Person providing a range of support and advice on issues related to employment to clients who are in and out of work. |

| EQ-5D-3L | A survey instrument for measuring health-related quality of life across the following five dimensions: mobility, self-case, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has three levels. The 3-level version was introduced in 1990 by the EuroQol Group. |

| Health state | A five-digit number that describes the patient’s health state in relation to five dimensions measured by the EQ-5D-3L. |

| IAPTUS | Case management software system for clients receiving psychological therapies in an IAPT service. |

| Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) | Programme that began in 2008 and delivers services that provide evidence-based psychological therapies to people with anxiety disorders and depression. |

| iMTA Productivity Cost | A measure of the number of days lost to workplace presenteeism - the extent to which an individual’s health conditions impact their ability to perform their usual workplace duties. This is calculated using the iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire (iPCQ). |

| Individual Placement and Support (IPS) | An employment support service integrated within community mental health teams for people who experience severe mental health conditions. It provides intensive, individual support to people to help them to move towards and into or stay in employment. |

| Jobcentre Plus (JCP) | Government-funded employment service that aims to help people of working age find employment. JCPs provide resources to enable jobsearchers to find work, offer information about training opportunities, and administer claims for benefits. |

| Logic model | A graphic which represents the theory of how an intervention produces its outcomes. It presents, in a simplified way, the hypothesis or ‘theory of change’ that process evaluations test. |

| ONS4 | A measure of personal well-being (PCB) developed by the Office for National Statistics. Respondents are asked four 11-point survey questions on life satisfaction, happiness, anxiety and feeling life is worthwhile. |

| PCMIS | Case management software system for clients receiving psychological therapies in an IAPT service. |

| Presenteeism | Refers to when individuals are in work but, because of illness or other medical conditions, not fully functioning. In many situations there is a productivity loss as an employee’s focus is not on the work due to illness or related distractions. |

| Productivity loss | A decrease in the effectiveness of productive effort in the workplace. In this reporting, productivity loss is measured in terms of the number of working days lost due to impairments causing inefficient working. |

| Propensity score matching | A statistical method for generating a matched comparison group for an intervention. It is useful in instances where data on a potential comparison group is available, but where there are observable profile or baseline differences between the intervention group and the comparison group. Propensity score matching generates weights for the comparison group which, when applied, reduce any such differences. |

| Reasonable adjustments | Refers to changes made to the work environment to remove barriers or disadvantages that enable people with a disability to work safely and productively. Under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010, ‘disability’ includes: physical, psychological or neurological disease or disorder, illness, whether temporary or permanent. |

| Senior Employment Adviser (SEA) | Manage and support a team of EAs in offering a support service to individuals with common mental health problems to gain, return to or retain employment. |

| Service Lead | Post-holder leading an EA service with overall responsibility for its delivery. |

| Service Provider | Contracted organisation that provides services on behalf of a CCG. |

| Statistical significance | a difference is said to have statistical significance, or be statistically significant, if it is likely not caused by chance for a given statistical significance level. In the current report, statistical significance is reported at a 95 per cent confidence level i.e. 95 per cent confident it did not happen by chance. |

| Time 1 | The time point at which clients were interviewed approximately five months after starting support through IAPT. |

| Time 2 | The time point at which clients were interviewed approximately twelve months after starting support through IAPT. |

| Wave One | Overall, 40 per cent of CCGs were selected for the trial. Wave One refers to those randomly-allocated (within the trial selection) where there was an increase in the number of Employment Advisers embedded in IAPT services from March 2018. CCGs selected for the trial |

| Wave Two | Overall, 40 per cent of CCGs were selected for the trial. Wave Two CCGs refers to those randomly-allocated (within the trial selection) where there was no increase in the number of Employment Advisers embedded in IAPT services from March 2019. |

| WHO-5 | The World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index assesses subjective psychological well-being to measure quality of life using a five-point scale across five statements. This gives a raw score of 0 to 25 where a higher score denotes better well-being. In this report, scores are also grouped into ‘unimpaired well-being’ (13 to 25), ‘impaired well-being’ (9 to 12) and ‘likely depressed’ (0 to 8). |

Summary

Introduction

This report forms part of the evaluation of the Employment Advisers in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (EAs in IAPT) programme. IAPT is a NHS England programme that provides evidence based psychological treatments for people with mental health problems, principally anxiety and depression. The EAs in IAPT delivery model has been designed as an integrated service that brings together employment advice and support with IAPT provision to enable IAPT clients to stay in or take up work. Both IAPT and EAs in IAPT are voluntary interventions.

EAs in IAPT is funded by the cross-government Work and Health Unit (WHU), jointly sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC).

Employment Advisers (EAs) provide employment support within the service, supporting clients typically falling into one of three categories: in work but struggling; employed but off work sick; or looking for work. Since 2008, EAs have been introduced in some IAPT services and findings from a pilot report (DWP, 2013)[footnote 1] suggest that they may be effective in supporting an individual back to work.

The WHU provided funding for approximately 350 additional EAs across IAPT services in 40 per cent of Clinical Commissioning Groups in England (CCGs; clinically-led statutory NHS bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of health care services for their local area), split into two waves. IAPT services in Wave One CCGs recruited their EAs so that they were ready to see clients from 1 March 2018, whilst services in Wave Two CCGs received investment later so that their EAs were in place to start to see clients on 1 March 2019. Allocation to Wave One and Wave Two was at random, and the Wave Two areas acted as a control group for Wave One.

In 2017, the WHU commissioned IFF Research, in partnership with ICF, Bryson Purdon Social Research (BPSR) and the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) at Sheffield University, to undertake a process and impact evaluation of the EAs in IAPT programme. The primary aim of this evaluation was to robustly determine the likely additional employment and health outcomes from receiving Employment Adviser support in an integrated care setting with IAPT services. A process evaluation looking at the implementation of the programme was published in July 2019.[footnote 2]

Methodology

This report draws on evidence from:

- A quantitative telephone survey with 1,609 Wave One IAPT clients – both those who saw an EA and those who did not – around five months after entering the service.

- A follow-up telephone survey with 755 Wave One clients who saw an EA, around 12 months after entering the service, and a corresponding survey with 609 Wave Two IAPT clients (including those who saw an EA and those who did not).

- Longitudinal qualitative interviews with EA clients from eight Wave One case study services, around five months after entering the service (with 55 clients) and a follow-up around six to eight months later (with 36 clients).

All fieldwork was carried out between January 2019 and March 2020. All fieldwork was completed before the national lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

This report explores the profile of EAs in IAPT clients, the experiences and longitudinal outcomes of these clients, and the impact of seeing an EA by comparing Wave One clients to clients who served as a counterfactual from Wave Two. Outcomes explored include work-related, job search activity, well-being and wider health outcomes.

Key considerations when interpreting results

It is important to note that clients included in this evaluation who received support from an EA did so at the start of the programme, when the service model was not yet fully embedded and national training for EAs had not been rolled out. Relatively small sample sizes (a by-product of the consent process outlined in Chapter 1) create limitations in some areas of analysis.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the sample is not representative of the whole EAs in IAPT pilot population; not all sites engaged with the consent process (and, thus, not all sites were included in the sample) and the sample is skewed towards those who took up EA support. This skew is due to EA clients being more likely than therapy-only clients to be asked to take part in the evaluation, although the extent of the bias is unknown as there is no reliable information on the population profile. Additionally, the small sample sizes mean that the impacts have to be very large before reaching statistical significance. Because of this, patterns of non-significant impacts are commented on in this report, even though the evidence they provide is relatively weak. Given these caveats, the estimates of impact should be treated as indicative only.

Such limitations are clearly flagged as and where relevant.

Another consideration when reviewing findings is that a ‘positive’ employment outcome and a ‘positive’ IAPT outcome may not always be aligned. For example, an individual may retain employment (considered a positive employment outcome) but this work could be negatively impacting their mental health and may result in future psychological treatment needs.

Client profile and support needs

The profile of EA clients

For all three key client groups of interest (employed and working, employed off sick and looking for work), the majority of IAPT clients sampled and surveyed in Wave One areas took up the offer of EA support. Those off work sick on entry to IAPT services were the most likely to take up EA support (79 per cent), as did a slightly lower proportion of clients looking for work (73 per cent) and around three-fifths (59 per cent) of clients who were employed and working.

Sampled and surveyed Wave One EA clients had a fairly even split between the three key employment groups: 36 per cent were employed and working, 30 per cent were employed off sick and 31 per cent were looking for work. Compared to those who took up EA support, IAPT clients who declined or were not offered a referral to EA support by their therapist were more likely to be in work (both 47 per cent).

Outside of the three key groups, small minorities of EA clients were employed but off work for other reasons (such as maternity or compassionate leave, one per cent) or retired and not looking to work in the future (two per cent).

Reasons for taking up EA support

For employed EA clients (including those working and off sick or off work for other reasons such as maternity leave), many took the service up because they felt it could help them with difficulties at work. Some of these clients were seeking help in managing their health conditions at work, for example through coping mechanisms or reasonable adjustments. Poor work relationships were also common, with some clients alluding to workplace harassment and bullying.

EA clients who were looking for work on referral mainly wanted help with the practicalities of applying for jobs such as CV writing, interview technique and knowing where to look for jobs. Those who had been out of the job market for a while or had left their previous job under stressful circumstances, often wanted help with confidence building for re-entry into the job market.

Apparent in all situations was the relationship between employment and mental health. Clients commonly described about how the situations they were seeking support with were both exacerbating and exacerbated by poor mental health.

Reasons for declining EA support

Among IAPT clients who declined the EA offer, many (44 per cent) gave reasons implying they had no employment needs. That said, other responses (such as prioritising health, 40 per cent, or already receiving support elsewhere, 17 per cent) imply employment issues were present for a decent proportion of these clients too.

Client experience of the EAs in IAPT service

Views of the EA service

Overall, experiences of the EAs in IAPT service were very positive. Just over threequarters (78 per cent) of EA clients surveyed agreed that the sessions had been useful, and the vast majority felt their adviser was understanding of their needs (92 per cent) and that the support they received was tailored (82 per cent). Clients were less positive when asked about the extent to which support helped them achieve key employment goals (e.g. to stay in work, return to work or find work), although over half (57 per cent) agreed it had.

In interviews with EA clients, EAs were highly commended for their friendly and flexible approach; clients particularly appreciated having a choice of how (i.e. face to face or via telephone) and how often sessions could take place and being able to maintain communication via email between sessions.

Furthermore, many clients commented that they appreciated receiving independent, non-judgmental advice, and that there was a good balance between practical, emotional and motivational support.

Client experiences also point to successful and valued integration between employment advice and therapy support with IAPT provision. Generally, clients felt the two elements of the service enhanced each other and created an effective holistic package.

Common employment activities

More than two-thirds (68 per cent) undertook at least four types of employment support activities with their EA. The most common activity was developing an action plan (77 per cent). Job search activities were common too; around three-quarters (74 per cent) explored how their skills could apply to other jobs and a third (32 per cent) had help with job interview techniques. Although more common among clients looking for work, these types of activities were prevalent among the employed. For example, 71 per cent of employed clients explored how their skills could apply to other jobs, compared to 80 per cent of clients who were out of work. This may reflect that many in work were unhappy with their current employment situation.

As mentioned, practical skills were often well balanced with emotional and motivational support. EAs provided emotional support through positive reinforcement of their abilities, encouraging them to stay with their employer where appropriate and reassuring the client that they would work together to address the difficulties with their employer. They provided advice on how to start difficult conversations with employers, for example, asking for adjustments at work through role play exercise.

Longitudinal outcomes for clients receiving EA support

Overall, more than two-thirds (68 per cent) of EA clients surveyed experienced a positive employment outcome between entry to IAPT and 12 months later; that is, they had either remained employed and in work (31 per cent), moved into employment (16 per cent) or returned to work after being on leave (21 per cent).

Other clients experienced more negative employment outcomes or no change. One in ten (10 per cent) clients had moved out of employment, 18 per cent remained out of work, and very small minorities had either remained employed but off work (three per cent) or moved from working to being on leave (one per cent).

It is important to note that the changes over time observed in this section are not necessarily attributable to the employment support received; some level of change may have resulted from the therapy alone, and some may have occurred without any intervention. That said, clients who saw an EA were asked the extent to which the support helped them to achieve their specific employment aim; these figures are presented in the subsections below.

Outcomes for those working on entry to IAPT services

The vast majority (87 per cent) of EA clients who were employed and working on entry to IAPT services were also working 12 months later – two-thirds (66 per cent) of these clients remained in the same role as on entry to IAPT. Just under two-thirds (63 per cent) of EA clients who stayed in work agreed that support from their EA had helped them do so.

Within this group, 91 per cent had experienced at least one positive in-work outcome during this time, with “softer” outcomes relating to experiences of work, workplace and job role adjustments and relationships most common. For most of these outcomes, the majority of clients felt support received from their EA and IAPT services played a role in the positive outcome. Clients were most likely to state that adjustments to job roles/responsibilities and working hours could be directly attributed to the service (27 and 26 per cent, respectively).

Improvements in presenteeism (an individual’s productivity at work being negatively affected by working whilst sick) were seen among this group, with the average number of days of productivity loss (in a four-week timeframe) decreasing from 6.10 across all working clients at the start of IAPT, to 1.72 days 12 months later.

Outcomes for those off work sick on entry to IAPT services

After twelve months, around seven in ten (69 per cent) clients who were off work sick on entry to IAPT services had returned to work, with fewer than half (44 per cent) returning to their previous job role. More than three-quarters (77 per cent) of clients who had returned to work felt the EA and/or IAPT service had helped them to do so, with more than half (56 per cent) ‘strongly agreeing’.

Presenteeism in this group reduced substantially between entry to IAPT services and approximately 12 months later. On average, these clients had a productivity loss of 7.91 days in the four weeks they were last in work before IAPT treatment; this decreased to an average of 1.21 days by 12 months.

Outcomes for those looking for work on entry to IAPT services

Half of EA clients (50 per cent) who were looking for work on entry to IAPT services had found work 12 months later. Nearly two-thirds (65 per cent) of clients who had found work agreed that IAPT services had helped them do so, with 48 per cent ‘strongly agreeing’.

As well as simply not being successful in finding a suitable job, reasons for being out of work at 12 months included a movement into education, taking on a voluntary role or caring responsibilities (all of which could be seen as positive outcomes), or job searching being affected by health.

The impact of EAs in IAPT support

The impact of EAs in IAPT support was measured by comparing the 12-month outcomes of IAPT clients who saw an EA against those of a matched[footnote 3] comparison group of IAPT clients from Wave Two areas, with similar IAPT baseline characteristics, who had not seen an EA. This report focuses on those looking for work and those off work sick when they began IAPT because it proved infeasible to identify a plausible comparison group for those employed and working when they saw the EA. Information collected on the reasons why people chose to see an EA suggests that two thirds (67 per cent) of those who saw an EA while in work did so because they were experiencing difficulties at work. No similar information was collected from those not seeing an EA, to allow for the identification of a plausibly similar comparison group for those employed and working.

Despite rigorous methods, for the two groups where impact estimates have been made, it is possible that the matched comparison groups may not give an unbiased estimate of the counterfactual. The comparison groups may have started with less acute employment problems and better well-being than the EA groups. If this is the case the impacts reported may be underestimated and some of the negative impacts may be spurious. Conversely, it could be that those in the out of workgroup seeing an EA were very actively engaged in seeking work and the out of work comparison group, on average, less so, in which case impacts on this group might be overestimated.

In addition, it should be noted that the sample sizes, particularly for the matched comparison groups, are small, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. There are 223 EA clients who were looking for work when they started IAPT, but just 68 in the comparison group. The numbers are very similar for the off work sick group, with 227 seeing an EA and just 70 in the comparison group. Given these caveats, the estimates of impact presented should be treated as indicative only.

Relative to their matched comparison group, those who were looking for work on IAPT entry and saw an EA were significantly more likely to be employed and working after 12 months than their matched comparison group. Half (48 per cent) of those who saw an EA were employed and working compared to three in ten (29 per cent) of the matched comparison group. The small samples sizes mean that impacts have to be very large before reaching statistical significance so patterns of non-significant impacts are commented on in this report, even though the evidence they provide is relatively weak. Among those still looking for work after 12 months, there is a consistent positive pattern of non-significant evidence that those who had EA support are both engaging in more job search activity and having a stronger desire to find work than their matched comparison group. For instance, 48 per cent of those who saw an EA reported higher levels of job search activity compared to 38 per cent of those in the comparison group. Similarly, those receiving EA support appear to be more likely to think they could consider entering work than the matched comparison group (85 per cent compared to 77 per cent). However, counter to this, they appear to be less confident that they will find work than the matched comparison group, although, again, the differences are not statistically significant (18 per cent compared to 35 per cent had higher confidence).

There is only one piece of statistically significant evidence for EA support having an impact on the well-being or health of those who were off sick when they started IAPT: those who had seen an EA are statistically significantly less likely to have reported visiting a GP in the previous two weeks (74 per cent versus 59 per cent had not done so). However, there is no statistically significant evidence of EA support having an impact on hospital outpatient or Casualty use or health-related quality of life (according to the EQ-5D measure) among this group.

There is very little statistically significant evidence of EA support having an impact on those who were in work but off sick when they began IAPT. However, there is nonsignificant evidence that they are in fact less likely to be employed and working after 12 months compared to their matched comparison group (72 per cent compared to 81 per cent). One possible explanation of this observed difference is that it may reflect a potential bias in the matched comparison group, with the EA group perhaps starting with more problems at work than the matched comparison group. An alternative hypothesis is that the EA group may be slower to re-enter work because liaison with employers is ongoing. Among the sub-set of those who had re-entered work after 12 months rather than being off sick, there is non-significant evidence that those who had seen an EA are less likely to report that their work is affected by physical or psychological health problems. There is no statistically significant evidence of EA support having an impact on health service use among this group.

Conclusions

A challenge of this evaluation was securing access to a representative sample of clients for the whole EAs in IAPT pilot population for the primary research. The variation in volumes of contact details provided by sites (with some services returning none at all) raises concerns about the consistency with which the process was applied. This, as well as the fact that these tended to be ‘early’ clients, means that the impact findings need to be treated with some caution.

That said, the conclusions that can be drawn from the evaluation to date are that:

- Those engaging with an EA were more likely to be in employment than looking for work and hence – to a large extent – EA support involved addressing difficulties at work.

- A close link between employment and mental health was evident among most patients seeking EA support.

- From a client perspective, EA support seems to have been delivered well.

- Across all client groups, qualitative research indicated that what really seemed to work in delivering EA support was the combination of practical, emotional and motivational support.

- A key intended outcome of the EAs in IAPT programme was to create an integrated service with therapeutic support and this was largely achieved from the clients’ perspective.

- Impact estimates found a positive impact from EA support on entry to work for clients who were looking for work on entry to IAPT. There was also an indicative (but non-significant) evidence of EA support having a positive impact on job search activity for those still looking for work at 12 months.

- Impact estimates did not find a positive impact on the likelihood to have returned to work among those who were off work sick.

- Impact estimates showed a positive impact in one area of healthcare utilisation; those off work sick and who had seen an EA were significantly less likely to have seen a GP in the previous two weeks. There were no other statistically significant health impacts.

1. Introduction

The Employment Advisers (EAs) in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme is funded by the Work and Health Unit (WHU), the crossgovernment unit, jointly sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). The service seeks to provide integrated psychological treatment and employment support to enable people to stay in, return to, or take up work. In 2017, WHU commissioned IFF Research, in partnership with ICF, Bryson Purdon Social Research (BPSR) and the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) at Sheffield University, to undertake a process and impact evaluation of the EAs in IAPT programme.

This report provides findings from the impact components of the evaluation of the EAs in IAPT programme. It draws on evidence from:

- A quantitative telephone survey with Wave One IAPT clients – both those who saw an EA and those who did not – around five months after entering the service.

- A follow-up survey with Wave One clients who saw an EA, around 12 months after entering the service, and a corresponding survey with Wave Two IAPT clients (both those who saw an EA and those who did not).

- Longitudinal qualitative interviews with clients from eight Wave One case study services, around five months after entering the service and a follow-up interview between six and eight months later.

All fieldwork was undertaken between January 2019 and March 2020.

1.1. The EAs in IAPT programme

IAPT, established in 2008, is an NHS England programme that provides evidence based psychological treatments for people with common mental health problems, principally anxiety and depression.

In 2009, an EA pilot pathfinder programme was introduced in 11 areas in IAPT services across England, which set out to test the benefits of offering employment support via Employment Advisers (EAs) to help IAPT clients remain in or return to work. Findings of a DWP evaluation in 2013[footnote 4] suggest that EAs may be effective in supporting an individual back to work. At the time of the 2013 report, the EA service was only available for employed clients, i.e. those working or those employed but off sick. A recommendation of the report was to expand access to include out of work clients. Shortly after its inception in 2015, WHU secured funding to extend the employment advice component of IAPT provision. The key catalyst in renewing the EAs in IAPT pilot was a policy recommendation in the 2014 RAND Europe report on psychological well-being and work,[footnote 5] which specified that vocational support should be embedded in local IAPT or psychological therapy services, based on the principles of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model.[footnote 6]

The programme adds additional capacity to deliver employment support to the target areas, by funding 350 additional EA posts across 40 per cent of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) over a three-year period. The original IAPT business case recommended a 1:8 ratio between EAs and Therapists and the additional funding added sought to bring the EA to therapist ratio closer to 1:8. The programme was rolled out in two waves: Wave One which went live in March 2018 and Wave Two which went live in March 2019. This was designed as a randomised control trial (RCT) between CCGs, with half the CCGs getting immediate funding (Wave One) and the others receiving extra investment a year later and acting as a control group (Wave Two) for the period without additional investment.

Each CCG or service directly recruited their EAs or commissioned a third party to provide them. The service has been designed to be managed and coordinated through the appointment of Senior Employment Advisers (SEAs) with the aim of ensuring that there is one SEA for up to a maximum of six EAs.

The EAs in IAPT delivery model has been designed as an integrated service that brings together employment advice and support with IAPT provision. Therapists and EAs are expected to work collaboratively to deliver a personalised service to clients based on their individual needs. The service is designed to support people with common mental health conditions who are either:

- In work but struggling or facing difficulties in the workplace;

- Employed but off work sick/suspended from work; or

- Looking for work.

Participation in employment support is voluntary and can be accessed at any point in the client journey from referral to discharge. Clients referred to the IAPT service are intended to follow one of four pathways according to their needs, although there is some variation between CCGs. Following assessment by a therapist they will receive:

1. Therapeutic treatment only;

2. Therapeutic treatment and employment support simultaneously;

3. Employment support continued beyond point of discharge/after their

therapeutic treatment has been completed;

4. Employment support while waiting for therapeutic treatment.

The approach is client-led so that if there are no pressing employment concerns during assessment or subsequent therapeutic sessions, only therapeutic treatment will be offered. If employment support is clearly indicated at the outset, pathway two or four (depending on the waitlist for therapy and considered appropriateness of starting employment support first) would be followed and if it only emerges later that employment is an issue, then pathway three would be followed.

As well as delivering an integrated employment advice and therapy service to the target group, the programme aims to contribute towards a wider systemic and cultural change, whereby structural barriers to integrated working around employment and health are challenged. At the local level, the intention was to support change through developing collaborative working relationships between EAs in IAPT providers and local employers, trade unions, Jobcentre Plus (JCP) and support organisations within the local labour market.

1.2. Research aims

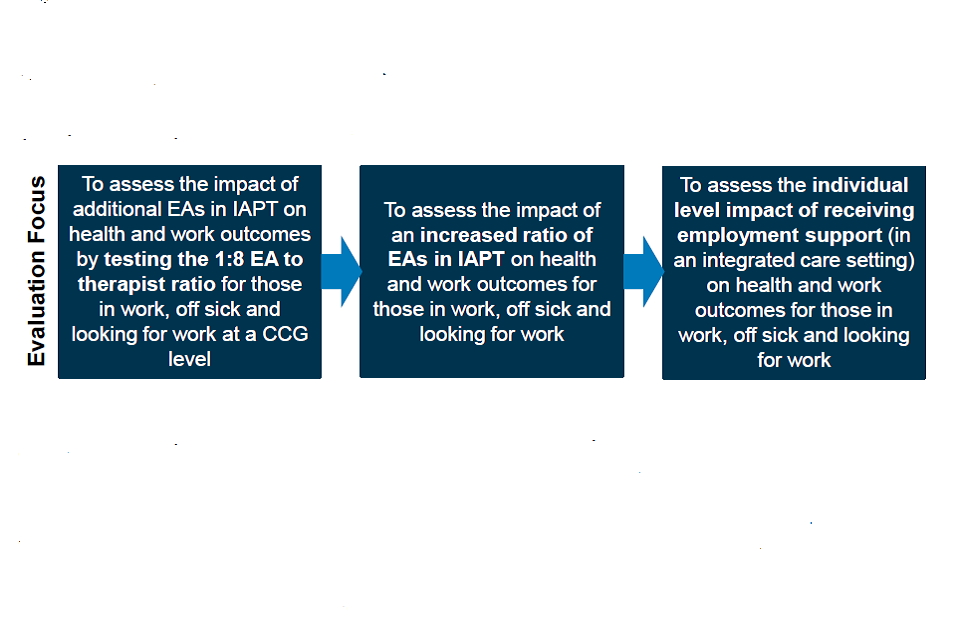

The focus of this evaluation has evolved over time, as shown below.

The original shift in focus from testing the ratio to testing an increased ratio was due to the limited likelihood of the 1:8 ratio being achieved and maintained across all Wave One providers in the evaluation period. It was then later decided that assessing the individual level impact of receiving EA support was a more primary focus than reviewing the impact of “more EAs” in an IAPT service, although analysis of the latter is included in Appendix C.

Ultimately, the primary aim of this evaluation was to robustly assess the likely additional employment and health outcomes from receiving Employment Adviser support in an integrated care setting with IAPT services. The evaluation aims to identify any differences in outcomes and experience for three key groups of clients, those:

- Employed and working – referred to as employed in work or working in this report unless otherwise specified

- Employed but off work due to health reasons – referred to as employed off work sick or off sick unless otherwise specified

- Out of work but looking to work in the future – referred to as looking for work in this report unless otherwise specified

Impact will be evaluated by comparing work and health outcomes for Wave One clients (who received treatment in a setting where the increased in EAs had been rolled out) and Wave Two clients (who did not see an EA and who received therapeutic treatment in a setting where the increased in EAs had not yet been rolled out). Thus, Wave One will be the treatment group and Wave Two will be the counterfactual group.

The results of the evaluation will inform the future design of integrated employment support in IAPT services and any further roll out decisions.

1.3. The evaluation approach

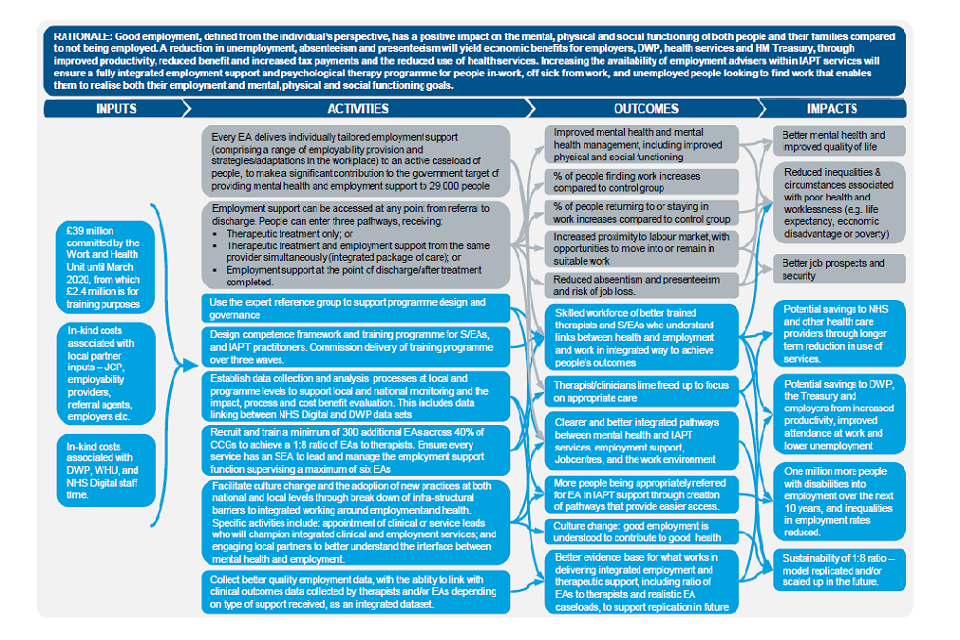

The evaluation began with a scoping phase designed to inform and develop the evaluation team’s understanding of the programme, refine the evaluation approach and develop a programme level theory of change (ToC) logic model. A review of the evidence for integrated work-related advice and support interventions for people with common mental health conditions was also undertaken by ScHARR at Sheffield University. The logic model is shown overleaf (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 EAs in IAPT logic model

Evaluation components were designed to gather process learnings and to test the theory of change by which intended outcomes of EAs in IAPT were met. The evaluation consists of five key components:

1. Case study visits to eight Wave One CCGs in which face to face, in-depth interviews were carried out with EAs, SEAs, therapists, programme coordinators and managers, and employability partners (such as Job Centre Plus), following the increase in EA numbers. These case studies provided process information in terms of what went well and areas for improvement during the process of increasing EA numbers in Wave One sites. In addition, the interviews with therapists and EAs explored some elements of impact, such as what it was about the EA support that helped clients.

2. A ‘Time 1’ survey of 1,609 clients, conducted just in Wave One areas approximately five months after the start of IAPT treatment. The timing of this survey was based on an average expected treatment length of 3-4 months. This survey focussed on the take up and experiences of receiving employment advice and also collected some early outcome data.

3. A ‘Time 2’ survey of 1,364 clients from Wave One (n=755) and Wave Two (n=609) approximately 12 months after the start of IAPT treatment. In Wave One areas only those who have received support from an EA were included. This survey allowed comparison of outcomes for those who received employment support in Wave One areas with ‘those who would have been likely to receive employment advice if the ratio of EAs had made it possible’ in Wave Two areas. This collected information on longer-term outcomes.

4. Client interviews: In-depth telephone interviews were carried out with clients who had experienced EA support within an IAPT service that had increased its EA numbers (i.e. Wave One areas). The interviews approximately five months after entry to IAPT services explored views on the EA support they had received, what benefits they gained from the support, and crucially, what elements of the support had contributed to these benefits, to understand what it was about the support that created any positive impact. Follow-up qualitative interviews were carried out with 36 of these clients around six to eight months after their initial interviews for the purposes of longitudinal analysis, to establish whether any benefits created by the support remained.

5. Further analysis of IAPT data (pending data access) to supplement the impact estimates reported on in Chapter 5 of this report.

This report builds on a previous process report, published in July 2019, which presented evidence from the eight case studies outlined in component 1 above.[footnote 7]

This report presents findings from qualitative and quantitative fieldwork with IAPT clients (evaluation components 2, 3 and 4 above) to explore the outcomes and impacts that can be attributed to the programme. Data collection methodologies for each component are outlined later in this chapter.

1.4 Recruitment and consent process

This study was confirmed by the Health Research Authority (HRA) as a Service Evaluation, meaning no further ethical approval from the HRA or Research Ethics Committee (REC) was required. However, due to the nature of the audience it was considered important to follow a thorough informed consent process before contact details were passed from IAPT providers to the research partners, and again when clients were directly contacted for the research.[footnote 8] An overview of the three-step consent process is provided in Figure 1.2 below, with further details in Appendix A. The process outlined below was followed for both qualitative and quantitative client interviews.

Figure 1.2 Overview of client consent process

As suggested by stakeholders, this consent process was designed primarily to avoid the potential distress for individuals with mental health conditions being contacted for research with no or limited prior knowledge.

It is important, however, to outline the methodological limitations of this approach, namely:

-

Small sample sizes: The process was heavily reliant on EAs and therapists taking time in their sessions to introduce the evaluation and gain consent. Some providers did not engage with the consent process at all (sample was not shared with the evaluation team in these cases) and others mentioned that it was not always deemed appropriate to discuss a research evaluation in their session, or clients did not meet the necessary threshold of appointments for doing so (i.e. they did not see an EA and had fewer than four therapy sessions). Ultimately, this had an impact on the volume of sample available for the research.

-

Bias in the sample: It is highly likely that those consenting differed from those who did not, and those who were asked for consent differed from those who were not (due to reasons outlined above). One by-product of the consent process is that clients in the research sample were more likely to have taken up EA support than those in the general IAPT population. This is because:

- EAs were more engaged and complicit with the consent process – anecdotal evidence from site visits indicated that the evaluation and collecting consent was more ‘top-of-mind’ for EAs than therapists, and therapists were less engaged in the process of introducing the research and collecting consent in their sessions. Driving the relative opposition from therapists were two concerns; many did not want to take treatment time away from clients within their appointment, and many felt it was inappropriate to mention given the content of discussions or the state of their clients.

- Therapy-only clients were required to reach their fourth appointment before consent was collected to avoid impact on treatment, but some clients left the service before reaching a fourth therapy appointment. EA clients, on the other hand, were asked in their first EA appointment.

1.5. Data collection for this report

Time 1 survey

The purpose of the Time 1 survey was to speak to Wave One clients relatively soon after they were likely to have finished receiving support through IAPT. An average length of time receiving IAPT support was identified as around three to four months, so the survey sought to speak to clients around five months after starting IAPT treatment.

The survey, conducted via telephone interview, explored the offer and experience of EAs in IAPT support and collected early outcome data (details on outcomes collected are outlined later in this chapter).

Sample

Sample was received directly from Wave One IAPT providers in monthly batches, between January and July 2019.

In total, useable[footnote 9] contact details were received for 3,268 Wave One IAPT clients for the purpose of the Time 1 survey. On receipt of the opt out letter, a total of 218 clients opted out before their fieldwork period, resulting in a starting sample of 3,050 records.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork took place between January and September 2019. On average, the survey took 22 minutes to complete.

A total of 1,609 telephone interviews were completed, a response rate of 53 per cent of the starting sample. A full breakdown of final sample outcomes is shown in Appendix B.

Within this survey, two-thirds (66 per cent) of clients had taken up EA support. Of these, 961 respondents agreed to re-contact for the Time 2 survey. This equates to a 91 per cent agreement to the follow-up.

Time 2 survey

The purpose of the Time 2 survey was to speak to both Wave One and Wave Two clients around 12 months after they started receiving IAPT treatment, to explore longer-term outcomes (details on these outcomes are explored later in this chapter). Again, this survey was conducted via telephone interview.

Sample

The vast majority of the sample for Wave One clients were those that took part in the Time 1 survey, received EA support, and agreed to re-contact (n=961). This sample was ‘topped up’ by a further 126 records who were not able to be included in the Time 1 survey. The top up sample was screened within the survey to determine whether they received EA support.

For Wave Two, the sample was received directly from IAPT providers. In total, useable[footnote 10] contact details for 1,012 Wave Two IAPT clients were received.

On receipt of the opt out letter,[footnote 11] a total of 51 clients opted out before their fieldwork period, resulting in a total starting sample of 2,048 records.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork took place between August 2019 and March 2020. A total of 1,364 interviews were completed – 755 for Wave One clients and 609 for Wave Two clients - with an overall response rate of 67 per cent of starting sample. On average, the survey took 20 minutes to complete.

The full breakdown for final sample outcomes can be found in Appendix B.

Qualitative interviews with clients

The purpose of the qualitative strand was to explore in greater depth how clients came to use the service, what support they received, whether they had experienced any benefits or impacts from the support received, as well as what specific elements of support they perceived to be the most useful/impactful.

Clients were contacted for depth interviews around five months after they started IAPT treatment and then follow-up around six to eight months later (12 months after starting IAPT treatment).

The interview at the five-month point focused on:

- The client’s experience of employment and the barriers they faced to finding or sustaining work;

- Their experiences of and perspectives on engaging with the EAs in IAPT service; and,

- Early benefits and impacts of the service, any areas for improvement and any future expectations or support needs.

Follow-up interviews (i.e. those at the 12-month point) focused on:

- What had happened since the client was first interviewed;

- Progress towards/into employment, returning to work after sick leave, or employment sustained, and changes in associated behaviours (interest in finding work, change in job search behaviour, etc.);

- A review of their future expectations and ambitions – including their confidence in finding or sustaining work;

- The extent to which the benefits of EA support received have been sustained and any factors that may have enabled or prevented this; and

- With hindsight, a review of their experience of EAs in IAPT to identify what worked well, what less so etc.

Sample

Clients were from one of eight case study areas (aligned with the eight areas selected for the process evaluation). The case study areas, selected from a possible 40 CCGs participating in Wave One of the programme, were as follows:

- Buckinghamshire CCG

- Camden CCG[footnote 12]

- City and Hackney CCG

- Dorset CCG

- East Riding of Yorkshire CCG

- Leicester City CCG

- Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CCG

- St Helen’s CCG

The following sampling approach was taken to maximise the range of contexts, thus ability to explore contextual factors and common enablers and challenges.

CCGs were chosen to include a mix of:

- NHS England regional teams;

- Rural, urban and combined rural/urban areas (as described at local authority level); and,

- Deprivation levels, as defined by the 2015 English Indices of Deprivation.[footnote 13]

The sample was agreed with WHU and where chosen areas did not give consent to participate (n=2), substitute areas with similar characteristics were selected.

A random selection of 348 records from case study areas - ensuring a spread by case study as far as possible – were invited to take part in the qualitative interviews. In total, 348 records were contacted for qualitative interviewing. The sample for the follow-up interviews (at the 12-month point) consisted of participants who agreed to be re-contacted at the end of their five-month interview (n=58). Clients who took part in the qualitative interview did not take part in the Time 1 or Time 2 surveys.

Fieldwork

A total of 55 depth interviews were completed via telephone at the five-month point (between February and March 2019). Follow-up interviews were conducted with 35 EA clients between September and December 2019. Table 1.1 shows the breakdown of interviews by the key employment groups.

Table 1.1 Number of qualitative interviews completed, by employment group

| Employment status on entry to IAPT | Five-month point | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

| Employed in-work | 49 | 23 |

| Employed off work sick | 4 | 3 |

| Looking for work | 14 | 10 |

| Total | 55 | 36 |

Analysis

Interviews were recorded, with participant consent,[footnote 14] and fully transcribed. Transcriptions were coded and analysed thematically using a framework analysis approach. Framework analysis is a systematic approach to analysing qualitative data. The approach enables the identification of common themes, and the differences and relationships between them, in order to draw explanatory conclusions clustered around key areas of interest.[footnote 15] The approach is particularly useful in the analysis of semi-structured interviews and when multiple researchers are working on projects that involve large amounts of qualitative data.

Following framework analysis, the results were written up under thematic headings before being synthesised with the quantitative findings.

1.6 Outcome measures

Drawing on the aims of the trial, the evaluation measured the impact of EAs in IAPT on a range of employment, job search, mental health and well-being outcomes, all collected in the quantitative surveys.

This section provides more detail on each of the outcome measures, including the points at which the data were collected and how it was analysed, divided into:

- Work-related outcomes;

- Job search related outcomes;

- Well-being outcomes; and,

- Wider health outcomes.

Outcome measure data was collected at three time points in reference to:

1. Entry to the IAPT service (baseline) – collected retrospectively for all survey participants. For Wave One clients who completed a Time 1 survey, baseline data was collected retrospectively within this survey, approximately five months after entering IAPT services. For all Wave Two clients, and the few Wave One clients who did not take part in a Time 1 survey, this data was collected retrospectively in the Time 2 survey, approximately 12 months after entering IAPT services.

2. Five months after entry to IAPT service – data for this time point was only collected for Wave One clients who completed the Time 1 survey.

3. 12 months after entry to IAPT services – data for this time point was collected for all Wave One and Two clients who completed a Time 2 survey.

Due to the nature of some outcome measures and the necessary timing of surveys, baseline data was not collected for all measures. Some measures were considered too difficult for clients to accurately recall retrospectively given the time that had passed since the time point, and the nature of the question. A summary of the time points for which we have data on each outcome measure is included in the sections below.

Work-related outcomes

A core aim of EAs in IAPT is to help people with employment-related issues which, are making it difficult to retain return to or find “good” work. As such, the impact of EAs in IAPT against the work-related outcomes was dependent on the client’s journey since entering IAPT. These outcomes and who they were measured for is shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Work-related outcome measures and audience asked

| Work-related issue | Remained employed and working | Returned to work from being off sick or off for other reasons | Moved into employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| More job satisfaction | Yes | No | No |

| More job enjoyment | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Better workplace relationships | Yes | No | No |

| Beneficial adjustments made in work | Yes | No | No |

| Improved career progression, prospects, and security | Yes | No | No |

| Improved presenteeism | Yes | Yes | No |

| Motivation and confidence to stay in work | Yes | Yes | Yes |

How each of these measures were collected and the timing or their collection is summarised below.

- The following questions were based on a ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’ response:

- Clients were asked whether they were getting more job satisfaction and enjoying their job more since they started receiving support through IAPT.

- Clients were asked if any of the following things which indicate better

workplace relationships had happened since receiving support through

IAPT:

- Your relationship with your employer has improved

- Your relationships with colleagues have improved

- Clients were asked if any of the following things which indicate beneficial

adjustments at work had happened since receiving support through IAPT:

- You have adjusted your working hours to suit you better

- You have increased your working hours

- You have changed your roles and responsibilities to suit you better

- Your employer has made adjustments to improve the working environment for you

- Clients were asked if any of the following things which indicate improved

career prospects, progression and security had happened since

receiving support through IAPT:

- Has your pay rate, salary or income increased?

- Have your future pay and promotion prospects improved?

- Do you have better job security?

- Your employer has a better understanding of how to maximise the contribution you can make at work

- A subset of questions from the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment (iMTA) Productivity Cost Questionnaire (PCQ) were used to assess impact of EAs in IAPT on presenteeism, for clients who were employed and working or employed but off sick on entry to the service and at subsequent survey points. Presenteeism relates to the notion that continuing to work despite illness, such as anxiety, can often result in reduced productivity. To ascertain presenteeism, survey respondents were asked in the four weeks before entering IAPT how many days they were bothered by psychological problems at work, and on those days to rate on a 0 to 10 scale how their work was affected by these problems (i.e. the efficiency score).)

To calculate lost productivity due to workplace presenteeism, the number of days worked while impaired is multiplied by ‘one minus the efficiency score divided by 10’ for these days:

Number of workdays impaired X [1 – (efficiency score/10)]

This determines the amount of time lost in the four weeks due to workplace presenteeism.

- Motivation for staying in work was measured with the question: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all and 5 means very, at this moment in time how motivated are you to stay in work?” Motivated was measured as ‘4’ or ‘5 - Very’.

- Confidence in staying in work was measured with the question: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all and 5 means very, at this moment in time how confident are you in staying in work?” Confident was measured as ‘4’ or ‘5 - Very’.

Table 1.3 Timing of data collection for work-related outcomes

| Work-related issue | IAPT start (retrospective) | Five-month point (W1 only) | 12-month point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment situation (in-work, off sick, looking for work) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Improvements in quality of job (i.e. “suitable” work) and relationships in the workplace | No | Yes | Yes |

| iMTA PCQ Presenteeism score | Yes | No | Yes |

| Motivation and confidence for staying in / returning to work | No | Yes | Yes |

| Job enjoyment | No | Yes | Yes |

Job search outcomes

Despite not entering employment as a result of EA support, a positive outcome would be evidence that someone is closer to entering work. The evaluation included a range of measures about people’s job search activity and propensity to look for work:

- Levels of job search activity are measured using the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health (FIOH) Job Seeking Activity Scale (Revised). This seven-item job search activity scale measures the frequency with which individuals undertake key job search activities, for example contacting employers or searching for job vacancies on the internet. The original version of this measure was developed at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health (FIOH)[footnote 16] and subsequently modified for use in the UK labour market.[footnote 17] The modified version has two additional items, to address online job search and CV submissions to internet search sites. Survey respondents are asked whether and how often they had undertaken a range of job search activities in the previous two weeks.:

A rating for each activity from ‘not at all’ to ‘every day’ over the past two weeks is used to create a scale from 1 (no job search) to 4 (scoring ‘every day’ on all seven items). The impact of EA support is measured using both the mean scale score and a binary variable where those scoring 1.0 to 1.6 are coded as doing ‘lower levels of job search activity’ job search and those scoring higher than 1.6 are coded as doing ‘higher levels of job search activity’. This binary was based on the comparison group data to produce roughly equal splits between high and low activity groups.

- Also an element of the JIOH Job Seeking Activity Scale, the number of vacancies applied for and number of CVs submitted in the past two weeks are categorised as two separate outcome variables and reported as a mean.

- Motivation for finding a job was measured with the question: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all and 5 means very, at this moment in time how motivated are you to find work?” Motivated was measured as ‘4 or ‘5 - Very’.

- Confidence in finding a job was measured with the question: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all and 5 means very, at this moment in time how confident are you in finding work?” Confident was measured as ‘4 or ‘5 - Very’.

Table 1.4 Timing of data collection for job search outcomes

| Job search outcomes | IAPT start (retrospective) | Five-month point (W1 only) | 12-month point |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIOH JSA scale (revised) | No | No | Yes |

| Jobs applied for | No | No | Yes |

| CVs submitted | No | No | Yes |

| Motivation for and confidence in finding work | No | Yes | Yes |

Well-being outcomes

In addition to helping clients with their employment goals, EA in IAPT could also improve mental health as measured by the IAPT Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) and the Anxiety Disorder Specific Measures (ADSMs). The evaluation measures the impact of EAs in IAPT on two well-being measures not collected as part of IAPT’s PROMS. This will be captured in the quantitative analysis. The evaluation measured the impact of EAs in IAPT on:

- The ONS4 Subjective Well-being questions ask individuals to rate themselves on a scale of 0 to 10 to four statements related to their well-being and life satisfaction:

“For the next questions, please give me an answer on a scale of zero to ten, where zero is not at all and ten is completely

- Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?

- Overall to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?

- Overall how happy did you feel yesterday?

- Overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?”

We report on the impact on the mean score of each item as well as the proportion scoring as ‘high’ (a score of 7 or more on satisfaction, feeling worthwhile and happiness, and 6 or more for anxiety). For the first three items, ‘high’ is a positive outcome, while for anxiety it is negative.

• The World Health Organisation-Five Well-being Index (WHO-5) is a five-item unidimensional measure of well-being with a good research pedigree. Individuals are asked to consider how often in the previous two weeks they have experienced particular feelings such as being in good spirits, feeling active and vigorous, calm and relaxed. This was asked across five statements. A score of 0 to 25 is derived by looking at responses across all statements. We report on the mean score where a higher score denotes better well-being. We also group scores into ‘unimpaired well-being’ (13 to 25), ‘impaired well-being’ (9 to 12) and ‘likely depressed’[footnote 18] (0 to 8).

Table 1.5 Timing of data collection for well-being outcomes

| Well-being outcomes | IAPT start (retrospective) | Five-month point (W1 only) | 12-month point |

|---|---|---|---|

| ONS4 Subjective Well-being | No | Yes | Yes |

| WHO-5 Well-being index | No | No | Yes |

Wider health outcomes

In addition to the mental health outcomes described above, the evaluation measured the impact of EAs in IAPT on client’s overall health, captured in the quantitative analysis via the EQ-5D[footnote 19] and use of health services during the past three months:

- The EQ-5D-3L[footnote 20] is a standardised measure of health status created by EuroQol. It comprises five questions, each of which asks about a different aspect of health (mobility, self-care, performing usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression). Focusing on how they feel today, people are asked to use a three-point scale to rate themselves as having no problems or issues (1) to it being extreme (3). Responses to the five questions can be aggregated to provide an overall health state score between 0 to 1, where a higher score denotes better health.[footnote 21]

- Self-reported visits to GP and engagement with mental health services (excluding IAPT) in the last two weeks and use of Casualty and Outpatients (excluding straightforward ante- or post-natal visits) services in the past three months are also used as measures of overall health.

Table 1.6 Timing of data collection for wider health outcomes

| Wider health outcomes | IAPT start (retrospective) | Five-month point (W1 only) | 12 month point |

| EQ-5D-3L health state | No | Yes | Yes |

| Engagement with health services | No | Yes | Yes |

1.7. About this report

Statistical differences

T-tests were used for comparing mean scores and z-tests for comparing percentages. The 95 per cent confidence level was used for establishing whether findings are significant or not, meaning we can be 95 per confident that the observed results are real and not an error caused by randomness.

Bold figures in tables indicate statistically significant difference to other subgroups displayed.

We have only reported relationships between data in the text of the report if they are statistically significant and if the relationship was thought to be relevant and/or interesting to the topic being discussed.

Relationships that were not statistically significant are not discussed in the text, except possibly in a few cases where an indicative relationship was thought to be relevant and/or interesting to the topic being discussed. Where this is the case, it has been made clear that the relationship is not significant.

Weighting

Data for this report has not been weighted.

It was not possible to weight the survey respondents to the EAs in IAPT pilot population due to a lack of accurate population data. Likewise, weighting to account for non-response at the five-month survey was not possible due to the following limitations with the sampling frame:

- Lack of demographic data in the sample frame

- There were indications of data inaccuracy in the original sample frame. For example, some individuals who were not marked as taking up EA support in the sample frame stated that they had done so within the survey. Findings from the pilot stage indicated that uptake of EA support is under-estimated in the original sample frame by approximately seven per cent.

- Inconsistency across CCGs for how support (whether EA support taken up; whether sought EA support to retain, return to or find work) and employment data (whether employed and working, employed but off work, or unemployed) were recorded in the sample frame.

The profiles of Wave One clients in the five- and 12-month surveys were compared to test for non-response bias. Owing to the low attrition between surveys, differences between the two profiles across key characteristics (age, gender, education level, employment status on entry and at five months, and subjective well-being) were negligible. As such, weighting was not required.

Key considerations when interpreting results

It is important to note that clients included in this evaluation who received support from an EA did so towards the start of programme roll out. There was good evidence in the Process Evaluation that processes earlier in the programme had not been streamlined, the service model lacked clarity and national training for EAs had not been rolled out. This means some areas identified for improvement by clients may be due to these earlier issues which have since been addressed.

Relatively small sample sizes (a by-product of the recruitment and consent process, as outlined earlier in this chapter) presented limitations in the analysis. For example, the sample sizes used in the estimation of impact are small and, as a result, only very large impacts would reach statistical significance. As a result, patterns of nonsignificant impacts are commented on in this report, even though the evidence they provide is relatively weak. Given these caveats, the estimates of impact should be treated as indicative only.

Limitations as outlined above are clearly flagged as and where relevant. Thoughts on how to address these limitations in the future are explored in the conclusions.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the sample is not representative of the wholeEAs in IAPT pilot population; not all sites engaged with the recruitment and consent process (and, thus, not all sites were included in the sample) and the sample is skewed towards those who took up EA support. This skew is due to EA clients being more likely than therapy-only clients to be asked to take part in the evaluation, although the extent of the bias is unknown as there is no reliable information on the population profile. Furthermore, sufficient population data for weighting against was not available. Reported findings should therefore be interpreted as findings for the research sample.

Another consideration when reviewing findings is that a ‘positive’ employment outcome and a ‘positive’ IAPT outcome may not always be aligned. For example, an individual may retain employment (considered a positive employment outcome) but this work could be negatively impacting their mental health and may result in future psychological treatment needs.

1.8. Structure of the report

Following this introduction, the report is structured into five chapters:

- Chapter 2 provides an overview of IAPT client profiles, including how EA clients differ from those who did not receive this support, and how the service was first introduced to clients;

- Chapter 3 explores the experiences of clients who took up EA support;

- Chapter 4 is a descriptive chapter exploring the longitudinal changes in work and health measures for clients who took up EA support, across the three key employment groups;

- Chapter 5 explores the impact of EA support by comparing Wave One clients to Wave Two counterfactuals; and

- Chapter 6 sets out conclusions and recommendations for future research on EAs in IAPT services.

2. Client profiles and introduction to the Employment Adviser (EA) service

This chapter presents the employment, demographic and health profiles of clients who took up Employment Adviser (EA) support, and how these characteristics compare to clients of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme who either declined this support or were not offered it. It is important to note that, due to the methodological limitations described in the introduction to this report, findings are representative of the research sample only, rather than the wider population. The chapter also explores why individuals decided to take up EA support, with findings drawn from both the survey and qualitative interviews with clients, and, conversely, why this support was declined by some IAPT clients.

Chapter summary

* Referrals into EA support tended to be two-staged; clients self-referred into IAPT (usually following signposting from a GP), then the therapy team

referred them into Employment Adviser (EA) support following an assessment.

* Relative to sampled IAPT clients who did not access the EA service, EA

clients were more likely to be in overtly negative employment situations, such as employed but off work sick or looking for work (thus, less likely to be employed and working).

* Within the survey sample, there were no notable differences in health or

demographic characteristics between clients who took up support and those

who declined it, but individuals who were not offered (or do not recall being

offered) EA support tended to be older, have lower educational qualifications

and were more likely to be White British than those offered employment

support.

* For employed EA clients, many took the service up because they felt it could help them with difficulties at work, such as managing their health conditions (e.g. through reasonable adjustments or coping mechanisms) or poor

workplace relationships (including harassment and bullying).

* EA clients who were looking for work on referral mainly wanted help with the practicalities of applying for jobs, or with confidence building for re-entry into the job market if they had been out of the job market for a while or had left their previous job under stressful circumstances.

* That said, clients generally had low expectations for the extent to which the service would help them with their employment issues.

* Apparent for all clients was the relationship between employment and mental

health. Clients commonly described how the work situations for which they

were seeking EA support were both exacerbating and exacerbated by poor

mental health.

* For IAPT clients who declined the EA offer, reasons pertaining to a lack of

employment support needs were most common, although a large minority

said that they wanted to prioritise health over employment at the time.

2.1. Overview of referral process

Figure 2.1 provides an illustration of the possible pathways a client might follow from referral to the IAPT service and subsequently to an EA through to service exit.[footnote 22]

Possible client pathway through the EA in IAPT service

Step 1. Client referred to IAPT service by GP or self-referral. Go to Step 2.

Step 2. Client offered employment support at assessment. If, offer accepted, go to Step 4. If not, go to Step 3. If the client doesn’t accept support, they can still accept it at a later stage.

Step 3. Client receives therapeutic support.

Step 4. Client referred to EA service. Go to Step 5 to continue assessment.

Step 5. More detailed assessment of support needs is done by phone or face-to-face. Go to Step 6.

Step 6. Either employment support or therapy starts first. Go to Step 7.

Step 7. Support is delivered at the same time. Support provided includes post-therapy.

2.2. Take up of EA support by employment group