Annual report on the Home Office forensic early warning system (FEWS), 2018 to 2019

Updated 4 April 2023

DSTL/PUB142578

20 August 2022

Dstl

Counter Terrorism and Security

Porton Down

Salisbury

Wilts

SP4 0JQ

Release conditions

© Crown copyright (2022), Dstl.

This material is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3) or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected].

Executive summary

The Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) was tasked by the Drugs Misuse and Firearms Unit (DMFU) of the Home Office to produce a summary of the outputs of the Forensic Early Warning System (FEWS) project during the financial year (FY) 2018 to 2019.

The aim of FEWS is to identify trends in new psychoactive substances (NPS) available in the United Kingdom (UK). The NPS trends identified by FEWS may be used as evidence to support future drug legislation. Any new substances which are not controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) 1971 can be commissioned for in-vitro testing (to determine whether a substance is capable of causing a psychoactive effect) in order to support the Psychoactive Substances Act (PSA) 2016. FEWS reports any newly identified NPS to the UK Focal Point who creates a watch list of substances within the UK.

During FY 2018 to 2019, Dstl coordinated collections to identify NPS from UK Border Force, UK prisons and from vulnerable groups. The findings of these collections have been collated and are summarised in this report. The control status of the drugs identified were correct at the time of collection.

In the Border Force collection, there was a slight increase in the variety of different NPS identified compared to the previous 2 years. Cathinones were the most prevalent type of NPS identified and it was the first reported UK occurrence of 2 of the cathinones identified; isohexylone and N-butylpentylone. It was also the first report of the novel synthetic opioid (NSO) furanyl UF-17 in the UK and EU. Seven of the NPS detected in the Border Force collections (DMAA, 3F‑phenmetrazine, mitragynine, furanyl UF‑17, harmaline, harmine and ostarine) were not controlled under the MDA at the time of collection.

Across the prison and vulnerable group collections, the predominant type of NPS detected were synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRA), and 5F-MDMB-PINACA was the most prevalent. Three SCRA were detected for the first time in the UK; 5C-PB22, 4F-MDMB-BINACA and CUMYL-4CN-BINACA and these were already controlled under existing legislation. The trend across the FEWS prison data showed that drug impregnated paper samples had doubled since the previous FEWS prison collection and this was the first year a drug had been identified in vape paraphernalia.

This was the second year that FEWS coordinated the analysis of samples seized from individuals within the homeless community and from immigration removal centres (IRC) and although the sample numbers were low, impregnated papers were also a common form of drug sample in this collection.

1. Introduction

1.1 Scope

During the financial year 2018 to 2019, the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) coordinated a collection to identify new psychoactive substances (NPS) at Border Force postal hubs, in prisons and in vulnerable groups across the UK, for the Forensic Early Warning System (FEWS) project.

1.2 New psychoactive substances

The term new psychoactive substances (NPS, sometimes referred to as a novel psychoactive substances) is used to describe substances that are produced to mimic the effects of traditional illicit drugs. These substances might not be recent innovations, but are considered new in that they are now being used recreationally as a drug or are newly available as a recreational drug in the UK. Other definitions of similar substances such as ‘legal highs’ are not fit for purpose as many NPS are now controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971[footnote 1] (hereafter referred to as the MDA), and therefore NPS can refer to both controlled and non-controlled substances.

The term NPS in this summary encapsulates all substances that have emerged in the UK recreational drug market since 2008. The addition of a drug to the MDA after 2008 does not exclude it from being referred to as an NPS. Therefore, an NPS has been defined throughout this summary as either a compound controlled by the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016[footnote 2] (hereafter referred to as the PSA) or a compound controlled by the MDA post-2008.

1.3 The Forensic Early Warning System

The aim of FEWS is to examine trends in the seizures of NPS in the UK such as prisons and border locations and to identify if any new substances emerge in the recreational drugs market. FEWS provides support to the PSA by determining if substances are capable of producing a psychoactive effect. Additionally, the data acquired by FEWS can be shared with the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) who may advise the government to control such substances under the MDA.

2. UK Border Force collections

2.1 Sampling

Dstl worked with Border Force to collect and identify NPS arriving in the UK at 5 fast parcel and postal hubs for the FEWS project.

The collection targeted seizures of suspected NPS samples sent via fast parcels and post. Samples seized by Border Force between April 2018 and February 2019 were submitted. Parcels and post are usually screened using a range of techniques including x-ray imaging, raman spectroscopy and colorimetric drug testing kits. Following an initial screening of consignments by Border Force employees, the FEWS team was notified of suspected NPS at the targeted hubs. These consignments were then submitted to forensic service providers (FSPs) within the FEWS NPS network for analysis.

2.2 Analysis

All the samples obtained for this collection were submitted to FSPs and were analysed using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). A total of 149 samples were submitted for analysis by these methods, with a further 5 samples that required further analysis involving nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and/or high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

2.3 Results

The summary of the results are detailed in Table 1. Border Force officers were requested to focus the sample collection on possible NPS samples, while the Joint Border Intelligence Unit (JBIU) shared lists of suspected NPS seizures at various postal hubs, which were subsequently sampled. As a result, the data obtained is not representative of all compounds seen at the borders. It is also outside the scope of this work to compare the number of NPS to the number of traditional drugs of abuse detected.

Table 1: NPS detected in samples from the Border Force collection

Controlled NPS

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| 5F-MDMB-PINACA | 4 | Class B |

| Methylmethcathinone | 3 | Class B |

| 4-Methylpentedrone | 2 | Class B |

| Methylethcathinone | 2 | Class B |

| N-Ethylhexedrone | 2 | Class B |

| N-Ethylnorpentedrone | 2 | Class B |

| Ephylone | 2 | Class B |

| Isohexylone | 1 | Class B |

| 5F-MDMB-PICA | 1 | Class B |

| ADB-FUBINACA | 1 | Class B |

| Alpha-PHP | 1 | Class B |

| Aminopropyl benzofuran | 1 | Class B |

| Chloromethcathinone | 1 | Class B |

| Chloroethcathinone | 1 | Class B |

| CUMYL-5F-PINACA | 1 | Class B |

| Dipentylone | 1 | Class B |

| N-Butylpentylone | 1 | Class B |

| MDPHP | 1 | Class B |

| Etizolam | 4 | Class B |

Non-controlled NPS

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| 3F-Phenmetrazine | 5 | Not controlled |

| Mitragynine | 5 | Not controlled |

| DMAA | 2 | Not controlled |

| Harmaline | 2 | Not controlled |

| Harmine | 2 | Not controlled |

| Furanyl UF-17 | 2 | Not controlled |

| Ostarine | 1 | Not controlled |

Controlled traditional drugs of abuse

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| Diamorphine | 1 | Class A |

| Ketamine | 2 | Class B |

| Amphetamine | 1 | Class B |

| THC | 1 | Class B |

| CBN | 1 | Class B |

| Alprazolam | 2 | Class C |

| Pregabalin | 2 | Class C |

| Androstendione | 1 | Class C |

| Methyltestosterone | 1 | Class C |

| Testosterone | 1 | Class C |

The number of occurrences in Table 1 is the total number of times a particular substance was encountered as either a single component or as a mixture with other drug substances. The total occurrence of a drug or a class of drug may therefore not match the number of samples analysed.

2.3.1 NPS occurrences

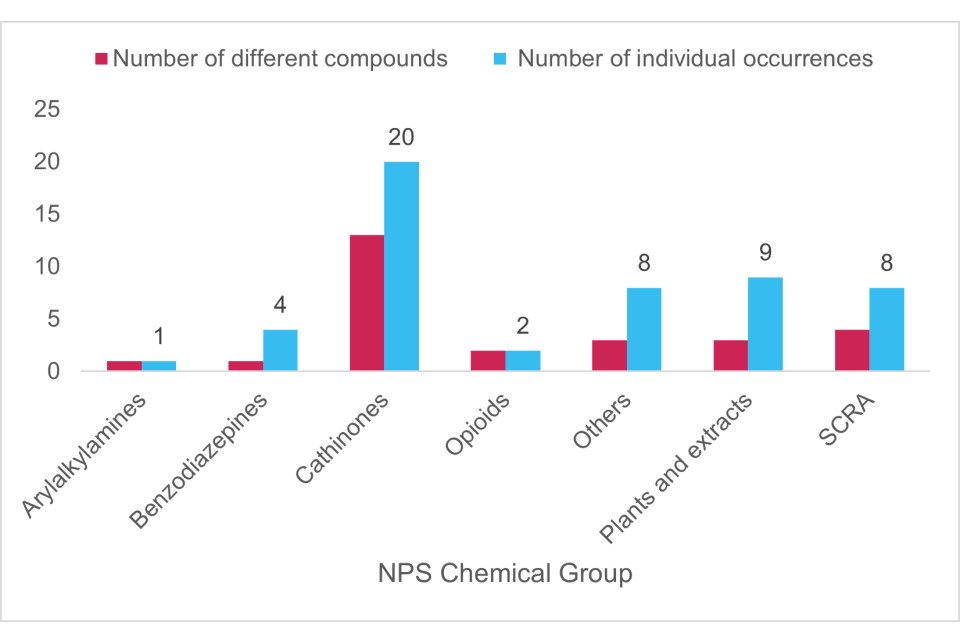

Out of the 149 samples analysed, 50 (34%) contained an NPS. There were 26 different NPS detected in total, 19 of which were controlled under the MDA at the time of collection. 50% of the NPS detected were cathinones; there were 13 different compounds in this category, while there were four (15% of NPS detected) SCRAs. The proportion of SCRA identified is smaller compared to the other FEWS NPS collections (those from vulnerable groups and prisons), where the majority of NPS detected were SCRA.

The most prevalent NPS seen in this collection were 3F-phenmetrazine and mitragynine, which were not controlled under the MDA at the time of collection, however they are covered under the PSA 2016. Both were seen on 5 occasions. Of the controlled NPS seen, 5F-MDMB-PINACA, a Class B SCRA, was the most prevalent. It was seen on four occasions and was also the most prevalent SCRA identified in the prison collection in 2018 to 2019.

Figure 1: Classes of NPS detected in samples from UK Border Force hubs. Graph shows the number of different compounds in each class (red), and the total number of individual NPS occurrences (blue).

Only 2 of the 50 samples with an NPS contained a mixture of 2 compounds (N‑ethylnorpentedrone and 4-methylpentedrone); the rest were single substance samples. 4-Methylpentedrone was also seen on its own in one other seizure. In total, 82% of the samples submitted contained only one compound whereas approximately 8% were mixtures of 2 or more compounds (Table 2).

Table 2: The number of compounds identified per sample

| Number of compounds per sample | Number of samples | Percentage of samples submitted (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16 | 11 |

| 1 | 122 | 82 |

| 2 | 10 | 7 |

| 3 | 1 | <1 |

Seven of the NPS identified were not controlled under the MDA at the time of collection (Table 1); these include DMAA, 3F-phenmetrazine and ostarine (classified as ‘others’ in Figure 1) and 3 plant extracts: mitragynine, harmanine and harmine, and furanyl UF-17.

At the time of collection, DMMA was being sold in dietary supplements online[footnote 3][footnote 4] and was reported to have stimulant properties. The Medicine and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued a warning about the potential danger of using the substance in early 2017.[footnote 5]

Furanyl UF-17, is an NSO with similarities to the controlled U-type drug U-47700 (Class A) and fentanyl. This was the first report of a seizure of this drug in the UK.

Harmaline and harmine were both identified as a mixture on 2 occasions in white powdered samples. The compounds are reported to be ‘hallucinogenic alkaloids’ found in a number of different plants including the ‘Ayahuasca’ plant found in South America[footnote 6][footnote 7]. This was the first report of both compounds identified in the FEWS project, however, police first reported harmine in the UK in 2004 following a raid of an illicit drug laboratory where the synthesis of harmine was being attempted. There were further reports of both compounds in 2005, 2008 and again in 2009 where they were detected in a brown tablet and a seed pod, vegetable matter and a powdered sample, respectively.[footnote 8]

Ostarine, a steroid hormone with anabolic activities, was detected in a package with capsules filled with white powder. The compound is classified as an NPS on the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addition (EMCDDA) NPS database.[footnote 9] At the time of collection, it was being sold on-line for weight training purposes and included in the World Anti-Doping Agency prohibited list.[footnote 10]

2.3.2 Other substances

Ten traditional drugs of abuse (Table 1) were identified in this collection plan with a combined total of 13 occurrences. These included diamorphine which was detected on its own without any adulterant, and ketamine, seen twice as a mixture with dextromethorphan, a known cough suppressant. Pregabalin, controlled as a Class C drug on 1 April 2019, was also identified, however the reported samples were seized prior to the change in legislation.

The controlled cannabinoids tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabinol (CBN), (Class B) were identified in a mixture with CBD (a non-controlled compound present in the cannabis plant). They were detected in a capsule filled with a ‘wet green substance’.

The other controlled compounds identified included three steroids, alprazolam, and amphetamine, which was seen in combination with caffeine. With the exception of the capsule containing THC, the other substances were identified in powdered or crystalline solid samples.

The non-controlled compounds are listed in Appendix A (Table 8). Six of the non-controlled substances identified are known precursors or starting materials to precursors, which are used in the production of other controlled compounds; these were:

-

Benzyl methyl ketone (BMK)

-

Piperonal

-

2-Phenylacetoacetamide (APAA)

-

Methyl α-acetylphenylacetate (MAPA, also referred to as Methyl 3-oxo-2-phenyl-butanoate)

-

Phenyl-2-nitropropene (P2NP)

-

N-methylnorfentanyl

BMK is subject to international control under the UN Convention against Illicit Traffic in narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 1988.[footnote 11] APAA was first seen in the 2017 to 2018 FEWS Border Force collection where it was identified in 6 separate consignments. APAA was first reported in the EU in 2015. APAA was voted for international scheduling under 1988 convention, during the UNODC’s 62nd Commission on Narcotic Drugs in March 2018[footnote 12], but was not yet subject to international control at the time of writing.

Sixteen of the samples submitted tested negative for any drug compound. A further 38 samples which did not contain any known drug compound by GC-MS were confirmed to be the dye henna by FTIR. Other non-controlled substances identified included voriconazole, an anti-fungal medicine reportedly used for life-threatening fungal infections; octacosanol, reported to be used as a sports performance enhancer [footnote 13]; 2,4-dinitrophenol, a fat-burning supplement which is classified as an explosive and a poison; caffeine and 4 other known cutting agents (Table 8).

2.3.3 Sample types

The majority of the samples submitted (66%) were described as powder, crystalline or rocky material. The remaining samples were herbal materials (27%), capsules (3%) and liquids (3%).

The majority (37) of the samples that contained NPS were in powder or crystalline material form, whereas the rest were capsules, liquids and herbal material. CUMYL-5F-PINACA was detected in 2 separate colourless liquid samples (in dropper bottles), labelled as ‘Kronic juice vape additive’. One brown liquid was found to contain mitragynine, while the remaining 4 samples in which mitragynine was identified were powders (1 brown and 3 green). ADB-FUBINACA and 5F‑MDMB-PINACA were identified in green herbal materials. The latter was also seen in lumpy powdered samples on 2 separate occasions.

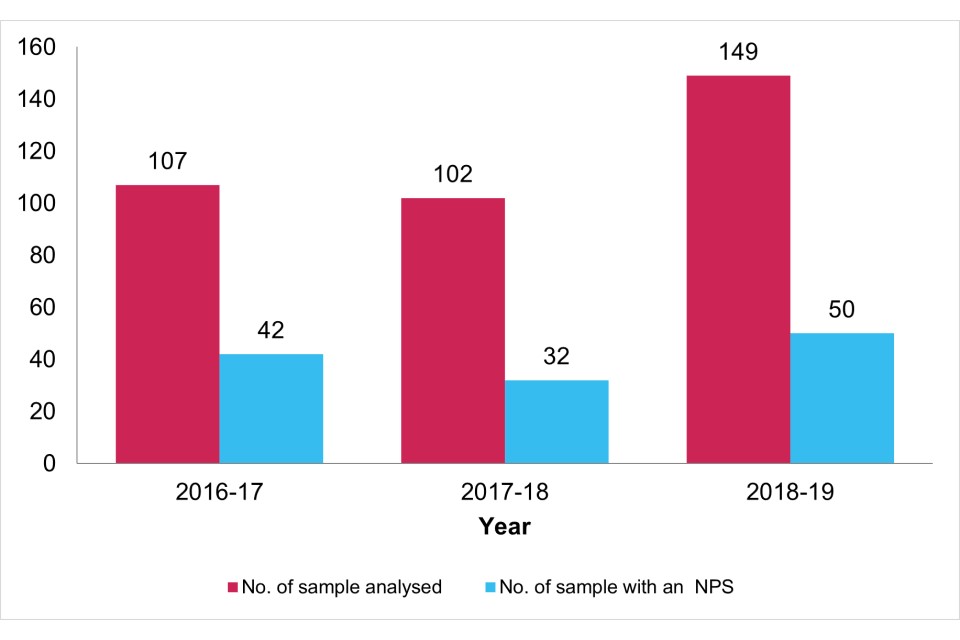

2.3.4 Previous collection trends

Although the overall number of samples analysed was relatively small, there was a 46% increase in the number of samples analysed compared to the 2017 to 2018 collection when 102 samples were submitted. However, a similar number of NPS were detected relative to the total number of samples analysed. Out of the 149 samples analysed this year, 34% contained an NPS, while in 2017 to 2018, 31% of the 102 samples analysed contained an NPS. There was a slight reduction when compared to the 2016 to 2017 collection where 39% of the samples analysed contained an NPS (Figure 2).

There was a slight increase in the variety of different NPS identified in 2018 to 2019 compared with the previous 2 years; 26 different NPS were identified in this collection, compared to 12 in 2017 to 2018 and 20 in the 2016 to 2017.

Figure 2: Number of samples submitted and number of NPS identified from 2016 to 2017 to 2018 to 2019.

In particular, the number of different cathinone compounds identified in the 2018 to 2019 collection is higher than in the previous 2 years; 14 cathinones were identified compared to 3 in 2017 to 2018 and 8 in 2016 to 2017. The other commonly encountered NPS group is SCRA, which has remained relatively low; there were 4 in 2016 to 2017, 5 in 2017 to 2018, and 4 again in this collection.

The most prevalent NPS in 2017 to 2018 was AMB-FUBINACA, which was identified in 10 seizures, this compound was only seen once in 2016 to 2017, but was not encountered this year.

2.4 Summary

Dstl facilitated the collection and analysis of suspected NPS samples seized by Border Force officials at 5 fast parcel and postal hubs. The samples were analysed as part of the FEWS project in order to determine which NPS were being sent via Fast Parcels into the UK. Border Force officers submitted samples seized between April 2018 and February 2019.

A total of 149 samples were analysed. 50 (34%) of the samples analysed contained an NPS. 26 different NPS were identified with a combined total of 51 occurrences. These include 19 compounds which were controlled under the MDA and 7 which were not controlled at the time of collection, however, these samples would likely be covered by the PSA 2016 pending in-vitro testing, thereby making the sale, import, and export of these substances illegal in the UK.

Cathinones were the most prevalent type of NPS identified, accounting for 50% of the total number of NPS identified. However, the most prevalent NPS detected were 3F-phenmetrazine and mitragynine; both compounds were not controlled under the MDA at the time of collection. Only one of the 50 samples with an NPS contained a mixture of two substances, the remaining contained a single compound. Furanyl UF-17 was seen in two separate seizures along with methylnorfentanyl. This was the first report of furanyl UF-17 and Isohexylone in the UK.

3. UK prison collections

3.1 Sampling

Samples were recovered from items found within prison grounds from March 2018 to February 2019. 14 different prisons participated from around the UK and 13 of these prisons participated in last year’s FEWS collection, so this has enabled comparisons to be drawn to previous data. The samples were classed as non-attributable samples as they cannot be linked to a person and, therefore, no legal charges can be raised for those samples.

An attributable sample is a seized sample where there is a suspect involved and therefore the sample can be attributed to a person or persons. Typically, attributable samples are seized and adopted by police for prosecution whereas non-attributable samples are usually marked for destruction. Data on attributable samples seized between March 2018 and February 2019 were provided to FEWS by a FSP. These samples were found on individuals within 18 different prison estates and were submitted for forensic analysis as part of casework.

3.2 Analysis

432 non-attributable samples were collected from 14 prisons across the UK. Samples were submitted to FSPs and were analysed using FTIR and GC-MS. Prison staff and coordinators were requested to focus sample collection on possible NPS samples; however, since it is not possible to visually identify a substance as a suspected controlled drug or NPS without subjecting it to some form of analysis, it was expected that a number of traditional drugs of abuse would be seen. Analysis of these traditional drugs of abuse was not the focus of this report; however, results of these identifications can be found in Appendix B.

3.3 Results

Table 3 shows a summary of results of analysis for NPS. In total, 432 samples were collected, of which 168 contained NPS. 48 different compounds were identified in this collection and 34 of these (71%) were controlled at the time of collection. 56% of the samples submitted contained only one compound whereas approximately 15% were a mixture of different compounds (Table 4). In 29% of the samples submitted, no substance was detected. This 29% consists of a large number of paper/card and tissue samples (69%). 14 different NPS were detected in total in the collection.

Table 3: NPS detected in non-attributable samples from the prison collection

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| 5F-MDMB-PINACA | 127 | Class B |

| AMB-FUBINACA | 59 | Class B |

| 5F-MDMB-PICA | 12 | Class B |

| 5F-AKB48 | 5 | Class B |

| MDMB-CHMICA | 4 | Class B |

| 5F-PB-22 | 3 | Class B |

| AMB-CHMICA | 3 | Class B |

| CUMYL-4CN-BINACA | 2 | Class B |

| 5F-PB-22 indazole analogue | 2 | Class B |

| AB-FUBINACA | 2 | Class B |

| AM-2201 indazole analogue | 1 | Class B |

| 4F-MDMB-BINACA | 1 | Class B |

| 4F-alpha-PHP | 1 | Class B |

| ADB-CHMINACA | 1 | Class B |

| Total | 223 | - |

The number of occurrences in Table 3 is the total number of times a particular substance was encountered as either a single component or as a mixture with other drug substances. The total occurrence of a drug or a class of drug will therefore not match the number of samples analysed as samples often contained more than one drug or no drugs.

Table 4: Number of compounds detected in each sample from the prison collection

| Number of compounds per sample | Number of samples | Percentage of samples submitted (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 127 | 29 |

| 1 | 240 | 56 |

| 2 | 44 | 10 |

| 3 | 18 | 4 |

| 4 | 1 | <1 |

| 5 | 2 | <1 |

3.3.1 NPS occurrences

All 14 NPS identified in this collection were controlled under the MDA at the time of seizure (Table 3). SCRA account for 99% of the NPS detected and all of the NPS samples contained at least one type of SCRA. NPS were detected in 95 herbal samples, 66 paper/card samples, 4 vape pens, 2 liquids and 1 brown substance sample.

5F-MDMB-PINACA and AMB-FUBINACA were the most prevalent NPS compounds detected and account for 83% of the NPS occurrences. Out of 168 SCRA samples, 42 (25%) contained a mixture of more than one SCRA. 4F-alpha-PHP is the only cathinone type NPS identified and this was detected on paper in a mixture with 2 SCRA; AMB-FUBINACA and AB-FUBINACA. SCRA were also detected as mixtures with tobacco, cocaine residues, and cannabinol (CBN).

4F-MDMB-BINACA and CUMYL-4CN-BINACA were detected in this collection and are both SCRA which are new to the FEWS project. These drugs have only recently been detected in UK police casework. 4F-MDMB-BINACA and CUMYL-4CN-BINACA were reported to the UK Focal Point for the first time in December 2018[footnote 14] and March 2019[footnote 15] respectively.

Data on attributable casework samples seized between March 2018 and February 2019 (Table 5) was provided to FEWS by a FSP. Four NPS were detected in these casework samples, and all of these were also present in the non-attributable samples. The prevalence of the NPS in attributable samples is similar to that in non-attributable data as 5F-MDMB-PINACA and AMB-FUBINACA were the most frequently occurring NPS. The range of NPS detected was less in the attributable casework samples but this may be due to the lower number of NPS occurrences in total; 67 compared to 223 (Table 3). This finding may reflect that the FEWS drug collection was focussed on suspected NPS whereas the attributable casework samples are representative of all laboratory submissions from the prisons. The abundance was similar for both years for the total number of other substances (shown in Appendix A: Table 9 and Table 10); 280 occurrences in 2017 to 2018 compared to 301 in this collection.

Table 5: NPS detected in attributable samples from the prison collection

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| 5F-MDMB-PINACA | 53 | Class B |

| AMB-FUBINACA | 11 | Class B |

| MDMB-CHMICA | 2 | Class B |

| 5F-MDMB-PICA | 1 | Class B |

| Total | 67 | - |

3.3.2 Other substances

19 different traditional drugs of abuse were detected in the non-attributable samples and the most prevalent drug was cannabis, equating to 44 occurrences from a total of 102. Other compounds included Class A drugs such as cocaine and diamorphine, and eight different Class C steroids. No substance was detected in 127 samples. The remaining 72 non-controlled occurrences comprised of tobacco, cutting agents and medicines (Appendix B: Table 10).

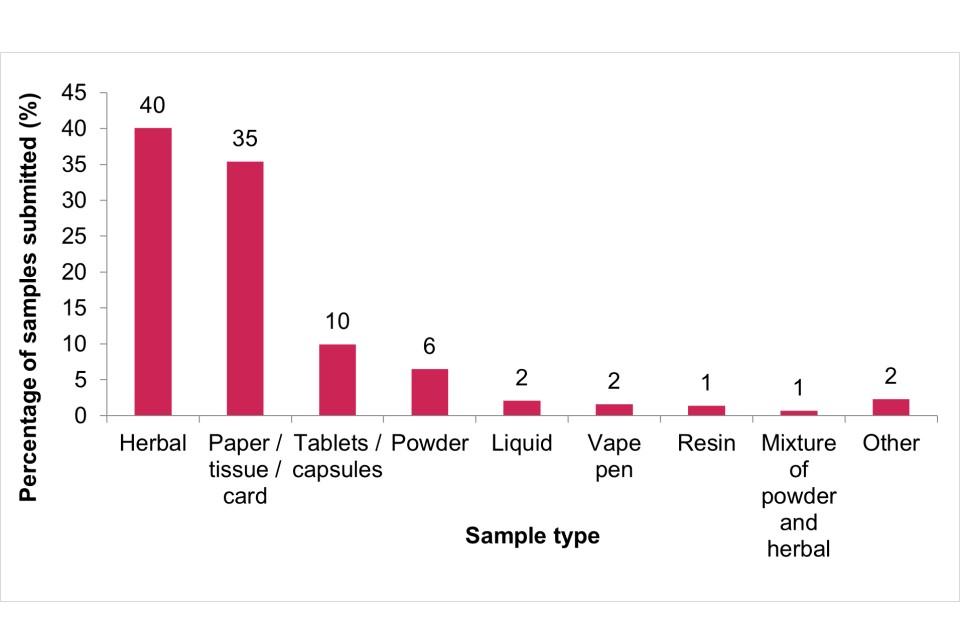

3.3.3 Sample types

A variety of sample types were seized (Figure 3) and the majority of the samples were herbal material (40%). The samples attributed to the “other” category included brown substances, a plastic bag and foil and these equated to approximately 2% of the samples seized.

Of the 153 paper, tissue and card samples, 66 (43%) samples were impregnated with at least one drug substance. Seven samples (2%) of the collection were vape pens. Five were found to contain controlled drugs; four of which were NPS (SCRA) and one was THC. One of the vape pens contained a mixture of 3 components: cannabinol, 5F-MDMB-PINACA and nicotine. Three samples (1%) consisted of a mixture of powder and herbal material. These were not found to contain controlled drugs and were identified as containing nicotine and caffeine.

Figure 3: Types of samples submitted for analysis for the prison collection.

3.3.4 Previous collection trends

13 of the prisons which participated in the 2017 to 2018 NPS collection were also part of this FEWS collection study. The findings of the collection show that the number of paper samples impregnated with drugs (66) has doubled since the previous collection (29), and has rapidly increased from only four samples detected in 2015 to 2016. This doubling, however, aligns with the increased number of paper samples submitted as part of the collection, and the percentage of paper samples which tested positive was the same as in 2017 to 2018 (43%). Last year, 66% of the samples were herbal and only 14% were paper whereas this year there were 40% herbal and 35% paper samples.

Vape pens are another method of drug concealment and five samples tested positive this year. No vape pens were submitted in last year’s FEWS collection plan so it is possible this method of concealment may be increasing in prisons. The phased introduction of smoke-free prisons began in Wales in March 2016[footnote 16] and was implemented in all prisons by the end of 2018[footnote 17][footnote 18]. Due to the smoking ban, vape pens have been made available to the prison population since an introductory pilot scheme in Wales in April 2016.[footnote 19]

There has been a year on year increase in the number of samples which tested negative; 127 in this collection compared to 82 last year and 28 in 2016 to 2017. 84 of the 127 samples were paper (66%); therefore the rise in negative samples may reflect the increased quantity of paper samples that were suspected to have been impregnated.

There were 14 different NPS in this year’s collection which is the lowest variation detected across all of the previous collection plans. The highest level of variation was detected in 2015 to 2016 with 23 different NPS found, and lowest prior to this year was in 2014 to 2015 with 15 different NPS. The most prevalent NPS in 2018 to 2019 was 5F-MDMB-PINACA, followed by AMB-FUBINACA. These 2 compounds were also the most frequent identified in 2017 to 2018, but variation in the prevalence has been seen across the years previously (Figure 4). Based on these results, 5F-MDMB-PICA prevalence could be considered to be increasing in prisons as it was not detected in FEWS collections before 2017 to 2018.

Figure 4: Order of prevalence since 2015 to 2016 for the top 7 NPS detected in the prison collection in 2018 to 2019.

There is variation in the NPS detected year to year as seen in Table 6. This table has been updated since the previous report – ‘Summary of the Forensic Early Warning System (FEWS) during 2017 to 2018’. In 2018 to 2019, only 3 compounds were unique to the collection plan that had not been seen in previous FEWS prison collections.

Table 6: NPS unique to each prison collection since 2014 to 2015

| 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB-22 | FUB-PB-22 | FUB-AKB48 | 5Cl-AB-PINACA | CUMYL-4CN-BINACA |

| AKB-48 | AB-PINACA | Diclazepam | Chloroethcathinone | 4F-MDMB-BINACA |

| ADB-PINACA | MDMB-CHMCZCA | 4F-alpha-PHP | ||

| MAM-2201 | Bk-MDEA | |||

| UR-144 | CUMYL-5F-PINACA | |||

| JWH-018 indazole analogue |

3.4 Summary

Dstl facilitated the collection of samples from 14 prisons across the UK from March 2018 to February 2019. 168 samples of NPS were detected from the 432 samples analysed. 14 different NPS were identified and all of these were controlled under the MDA. 99% of NPS occurrences were SCRA and 4F-alpha-PHP (a cathinone) was the only other NPS identified.

5F-MDMB-PINACA and AMB-FUBINACA were the most prevalent NPS in the collection and account for 83% of the NPS occurrences.

The number of papers impregnated with a drug has doubled since last year’s FEWS NPS collection and vape pens appear to be increasingly utilised as a method of drug concealment.

The non-attributable FEWS data was compared to attributable casework data supplied by a forensic service provider. The data did not show any other NPS which was not captured in the attributable data and the order of prevalence of NPS was similar.

Analysis of the FEWS prison data collected since 2014/15 shows that the order of prevalence of specific SCRA varies year to year. However, there are common preferences, and this year, the two most prevalent NPS were also the most prevalent last year. Three of the NPS seen in 2018 to 2019, 4F-MDMB-BINACA, CUMYL-4CN-BINACA and 4F-alpha-PHP, had not been reported in previous FEWS prison collection plans. Of these, the two SCRA are new to the UK; 4F-MDMB-BINACA was reported in December 2018 and CUMYL-4CN-BINACA was reported in March 2019.

4. Vulnerable group collections

4.1 Sampling and analysis

Dstl facilitated the analysis of samples suspected to contain NPS seized from within two vulnerable group communities between April 2018 and February 2019. The FEWS team coordinated the analysis of samples seized by the police as part of routine patrols from individuals within the homeless community. A second route of collection was carried out in partnership with 3 immigration removal centres (IRC) collecting non-attributable samples. The samples were submitted to FSPs within the FEWS NPS network and were analysed using GC-MS.

4.2 Results

In total, 109 samples were received for analysis, which included 2 samples from the homeless community and 107 samples from IRC. A further 9 samples submitted from IRC were not analysed as they were cannabis which was visually identified.

NPS occurrences

Out of the 109 samples analysed, 41 (38%) were found to contain an NPS; this included the 2 samples provided by the police and 39 of the samples submitted by IRC. Seven different NPS were identified; these included 5 SCRA (which accounts for 50 (96%) of total NPS occurrences), a cathinone and one benzodiazepine; see Table 7. All 6 compounds were controlled under the MDA at the time of collection.

5F-MDMB-PINACA was the most prevalent compound detected in this collection. It was detected in 35 samples and accounted for 69% of total NPS occurrences. It was seen as a single substance (26 occurrences) and as a 2 or 3 component mixture with other SCRA, namely a combination of AMB-FUBINACA, 5C-PB22 and 5F-MDMB-PICA (6 occurrences). It was also detected with trace amounts of 4-chloroethcathinone as well as nicotine, in 1 and 2 samples respectively. Diclazepam, a controlled (Class C) benzodiazepine, was detected on one occasion in white tablet fragments. AMB-FUBINACA was also seen on its own and as a mixture with 5F-MDMB-PICA.

This collection identified 5C-PB22, which was the first reported occurrence in FEWS and in the UK. The compound was identified on printed paper along with 2 other compounds highlighted above.

APP-BINACA, a Class B SCRA, was identified on white lined paper submitted by one of the IRC. This was the first report of this compound through the FEWS project, however it was first reported in the UK in December 2018 as part of a police casework sample.[footnote 20] According to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction’s NPS notification database, the compound had not been reported by any other European countries, but had been reported in the United States.[footnote 21] 5F‑MDMB‑PICA was also relatively new to the UK at the time of collection; it was seen in the FEWS 2017 to 2018 Prison collection and was first reported to the UK Focal point in June 2018. The other 2 SCRA identified have been seen in the UK since 2016. All the NPS identified in this collection were controlled under the MDA at the time of collection.

Table 7: Results obtained from the vulnerable group collection

NPS

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| 5F-MDMB-PINACA | 35 | Class B |

| AMB-FUBINACA | 8 | Class B |

| 5F-MDMB-PICA | 5 | Class B |

| 4-Chloroethcathinone | 1 | Class B |

| 5C-PB22 | 1 | Class B |

| APP-BINACA | 1 | Class B |

| Diclazepam | 1 | Class C |

Controlled traditional drugs of abuse

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | 1 | Class A |

| Diamorphine | 1 | Class A |

| Cannabis | 28 | Class B |

| Ketamine | 1 | Class B |

| Methandienone | 1 | Class C |

| Tramadol | 1 | Class C |

Other

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| Mirtazapine | 3 | Prescription only medicine |

| Nicotine | 17 | Not controlled |

| Negative | 16 | Not controlled |

| Paracetamol | 3 | Not controlled |

| Promethazine | 3 | Not controlled |

| Caffeine | 1 | Not controlled |

| Dicyclomine | 1 | Not controlled |

| Dihydrocodeine | 1 | Not controlled |

| Unidentified material | 1 | N/A |

The number of occurrences in Table 7 is the total number of times a particular substance was encountered as either a single component or as a mixture with other drug substances. The total occurrence of a drug or a class of drug will therefore not match the number of samples analysed as samples often contained more than one drug or no drugs.

4.2.2 Sample types

The majority of the samples from IRC were green herbal material or paper that appeared to have been impregnated. Out of the 41 samples which contained an NPS, 14 were paper samples, 26 were green herbal material, and one was a white tablet.

The 2 samples submitted by the police were green herbal material. One contained a mixture of AMB-FUBINACA and 5F-MDMB-PICA, whilst the second contained 3 different SCRA; AMB-FUBINACA, 5F-MDMB-PICA and 5F‑MDMB-PINACA.

4.2.3 Other substances

Six traditional drugs of abuse were detected in the samples analysed. 28 of the 107 samples submitted by the IRC contained THC, including cannabis resin and herbal cannabis samples. The other controlled drugs detected were cocaine, diamorphine, ketamine, methandienone and tramadol. Apart from the tramadol sample, which contained paracetamol and dicyclomine, the other 4 compounds were detected as single components.

Mirtazapine, a prescription only anti-depressant, was seen on 3 separate occasions in tablet form (1 orange tablet and 2 yellow tablets).

Seventeen samples did not contain a drug compound. These samples included loose seeds, paper (including a letter), tablets, resinous materials, cigarette papers, and green herbal materials. The remaining samples contained promethazine (an antihistamine), nicotine, paracetamol and caffeine (Table 7).

4.3 Summary

Dstl analysed suspected NPS samples seized from the homeless community and non-attributable samples found on the premises at 3 IRC between March 2018 and February 2019.

A total of 109 samples were submitted for analysis. The majority of these were submitted by the IRC (107 samples), whereas the police submitted 2 samples seized from individuals. From the samples analysed, 41 (38%) contained one or more NPS. Seven different NPS were identified with a combined total of 52 occurrences. These include five SCRA (5C‑PB22, 5F-MDMB-PINACA, 5F-MDMB-PICA, AMB‑PINACA, APP‑BINACA), 4‑chloroethcathinone and diclazepam. All the NPS identified were controlled under the MDA.

From the NPS occurrences, 50 (96%) were of SCRA and 5F‑MDMB‑PINACA was the most prevalent NPS detected. The majority of the samples with an NPS were green herbal materials (26 samples), while there were 14 paper samples impregnated with an NPS. Diclazepam was identified in a white tablet. 5C-PB22 was identified along with 5F-MDMB-PINACA and 5F-MDMB-PICA on an impregnated printed paper sample. This was the first report of 5C-PB22 in FEWS and in the UK.

The aim of this collection was to gather data on the prevalence of NPS within two vulnerable groups; IRC and the homeless community and to determine whether new NPS were being encountered in the UK in these settings. While the sample numbers were relatively small, the results show that NPS were being used within these communities and that the majority of the NPS encountered were SCRA. The latter is similar to what had been seen in the FEWS prison collections over the previous 5 years.

List of chemical names

AB-FUBINACA

Chemical name

N-(1-Amino-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

AB-PINACA

Chemical name

N-(1-Amino-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-pentyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

ADB-CHMINACA

Synonyms

MAB-CHMINACA

Chemical name

N-(1-Amino-3,3-dimethyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

ADB-FUBINACA

Chemical name

N-(1-amino-3,3-dimethyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

ADB-PINACA

Chemical name

N-(1-Amino-3,3-dimethyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-pentyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

AKB48

Synonyms

APINACA

Chemical name

N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-1-pentyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

Alpha-PHP

Synonyms

alpha-Pyrrolidinohexanophenone

Chemical name

1-Phenyl-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)hexan-1-one

AM-2201 indazole analogue

Synonyms

5F-JWH-018-N, 5F-THJ-018 and THJ-2201

Chemical name

(1-(5-Fluoropentyl)-1H-indazol-3-yl)(naphthalen-1-yl)methanone

AMB-CHMICA

Chemical name

Methyl (1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indole-3-carbonyl)-L-valinate

AMB-FUBINACA

Synonyms

FUB-AMB and MMB-FUBINACA

Chemical name

Methyl (1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carbonyl)-L-valinate

APAA

Chemical name

3-Oxo-2-phenylbutanamide

APAAN

Chemical name

3-Oxo-2-phenylbutanenitrile

APP-BINACA

Synonyms

APP-BUTINACA

Chemical name

N-(1-Amino-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl)-1-butyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

Bk-MDEA

Synonyms

Ethylone

Chemical name

1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-(ethylamino)propan-1-one

BMK

Synonyms

Benzyl methyl ketone

Chemical name

1-Phenylpropan-2-one

CBD

Synonyms

Cannabidiol

Chemical name

5’-Methyl-4-pentyl-2’-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-1’,2’,3’,4’-tetrahydro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2,6-diol

CBN

Synonyms

Cannabinol

Chemical name

6,6,9-Trimethyl-3-pentyl-6H-benzo[c]chromen-1-ol

5C-PB22

Chemical name

Quinolin-8-yl 1-(5-chloropentyl)-1H-indole-3-carboxylate

5Cl-AB-PINACA

Chemical name

N-(1-Amino-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-(5-chloropentyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

CUMYL-4CN-BINACA

Synonyms

4-CN-BINACA-ADB, 4-CN-CUMYL-BINACA, 4-CN-CUMYL-BUTINACA, CUMYL-CB-PINACA, CUMYL-CYBINACA, SGT-78

Chemical name

1-(4-Cyanobutyl)-N-(2-phenylpropan-2-yl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

CUMYL-5F-PINACA

Chemical name

1-(5-Fluoropentyl)-N-(2-phenylpropan-2-yl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

DMAA

Synonyms

1,3-Dimethylamylamine

Chemical name

4-Methylhexan-2-amine

5F-AKB48

Synonyms

5F-APINACA

Chemical name

N-((3s,5s,7s)-Adamantan-1-yl)-1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

4F-Alpha-PHP

Chemical name

1-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)hexan-1-one

4F-MDMB-BINACA

Synonyms

4F-MDMB-BUTINACA

Chemical name

Methyl 2-(1-(4-fluorobutyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamido)-3,3-dimethylbutanoate

5F-MDMB-PICA

Synonyms

5F-MDMB-2201 and MDMB-2201

Chemical name

Methyl 2-[[1-(5-fluoropentyl)indole-3-carbonyl]amino]-3,3-dimethyl-butanoate

5F-MDMB-PINACA

Synonyms

5F-ADB

Chemical name

Methyl 2-[1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamido]-3,3-dimethylbutanoate

5F-PB-22

Chemical name

Quinolin-8-yl 1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indole-3-carboxylate

5F-PB-22 indazole analogue

Synonyms

5F-NPB-22 and QCBL(N)2201

Chemical name

Quinolin-8-yl 1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylate

FUB-AKB48

Chemical name

N-((3s,5s,7s)-Adamantan-1-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide

FUB-PB-22

Synonyms

QCBL-Bz-F and MN-27

Chemical name

Quinolin-8-yl 1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indole-3-carboxylate

JWH-018 indazole analogue

Chemical name

1-Naphthalenyl(1-pentyl-1H-indazol-3-yl)-methanone

MAM-2201

Chemical name

(1-(5-Fluoropentyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)(4-methylnaphthalen-1-yl)methanone

MAPA

Chemical name

Methyl 3-oxo-2-phenylbutanoate

MDMB-CHMCZCA

Chemical name

Methyl 2-(9-(cyclohexylmethyl)-9H-carbazole-3-carboxamido)-3,3-dimethylbutanoate

MDMB-CHMICA

Synonyms

MMB-CHMINACA

Chemical name

Methyl 2-(1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indole-3-carboxamido)-3,3-dimethylbutanoate

MDPHP

Chemical name

1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)hexan-1-one

P2NP

Chemical name

(E)-(2-Nitroprop-1-en-1-yl)benzene

PB-22

Chemical name

Quinolin-8-yl 1-pentyl-1H-indole-3-carboxylate (also known as QUPIC)

PMK methyl glycidate

Chemical name

Methyl 3-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-methyloxirane-2-carboxylate

THC

Chemical name

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol

U-47700

Chemical name

3,4-Dichloro-N-((1R,2R)-2-(dimethylamino)cyclohexyl)-N-methylbenzamide

UR-144

Chemical name

(1-Pentyl-1H-indol-3-yl)(2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropyl)methanone

List of abbreviations

ACMD

Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs

DMFU

Drugs Misuse and Firearms Unit

Dstl

Defence Science and Technology Laboratory

EMCDDA

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

FEWS

Forensic early warning system

FSP

Forensic service provider

FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

FY

Financial year

GC-MS

Gas chromatography mass spectrometry

IRC

Immigration removal centres

JBIU

Joint Border Intelligence Unit

LC-MS

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

MDA

Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

MHRA

Medicine and Healthcare Regulatory Agency

NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

NPS

New psychoactive substances

PSA

Psychoactive Substances Act 2016

SCRA

Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists

UNODC

United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime

UK

United Kingdom

Appendix A: Summary of other substances detected in the Border Force collection

Table 8: Other substances detected in samples from the Border Force collection

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| APAA | 2 | Not controlled |

| BMK | 2 | Not controlled |

| Furanylnorfentanyl | 2 | Not controlled |

| N-Methylnorfentanyl | 2 | Not controlled |

| Phenyl-2-nitropropene | 1 | Not controlled |

| Piperonal | 1 | Not controlled |

| PMK methyl glycidate | 1 | Not controlled |

| Benzocaine | 12 | Not controlled |

| Phenacetin | 3 | Not controlled |

| Caffeine | 2 | Not controlled |

| Lignocaine | 2 | Not controlled |

| Levamisole | 1 | Not controlled |

| Henna | 38 | Not controlled |

| Negative | 16 | N/A |

| Dextromethorphan | 2 | Not controlled |

| Methyl 3-oxo-2-phenyl-butanoate | 2 | Not controlled |

| 6-hydroxy-4-methyl-2-oxo-1-propyl-1,2-dihydropyridine-3-carbonitrile | 1 | Not controlled |

| Arabic Gum | 1 | Not controlled |

| 2,4-Dinitrophenol | 1 | Not controlled |

| IDRA-21 | 1 | Not controlled |

| Mitronidazole | 1 | Not controlled |

| Octacosanol | 1 | Not controlled |

| Voriconazole | 1 | Not controlled |

Appendix B: Summary of other substances detected in the prison collection

Table 9: Traditional drugs of abuse detected in non-attributable samples from the prison collection

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| Diamorphine | 8 | Class A |

| Cocaine | 6 | Class A |

| 6-monoacetylmorphine | 2 | Class A |

| MDMA | 2 | Class A |

| Cannabis / THC / resin | 44 | Class B |

| Codeine | 2 | Class B |

| Cannabinol | 1 | Class B |

| Oxymetholone | 12 | Class C |

| Methandienone | 4 | Class C |

| Testosterone | 4 | Class C |

| Nandrolone | 3 | Class C |

| Trenbolone | 3 | Class C |

| Buprenorphine | 2 | Class C |

| Gabapentin | 2 | Class C |

| Methyltestosterone | 2 | Class C |

| Stanozolol | 2 | Class C |

| Dihydrocodeine | 1 | Class C |

| Oxandrolone | 1 | Class C |

| Zopiclone | 1 | Class C |

| Total | 102 | - |

Table 10: Other substances detected in non-attributable samples from the prison collection

| Substances | Occurrences | Classification under MDA |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 127 | Not controlled |

| Nicotine / Tobacco | 36 | Not controlled |

| Caffeine | 18 | Not controlled |

| Paracetamol | 4 | Not controlled |

| Mirtazapine | 3 | Not controlled |

| Quetiapine | 2 | Not controlled |

| Duloxetine | 1 | Not controlled |

| Flucloxacillin | 1 | Not controlled |

| Phenacetin | 1 | Not controlled |

| Promethazine | 1 | Not controlled |

| Sertraline | 1 | Not controlled |

| Sildenafil | 1 | Not controlled |

| Sofosbuvir | 1 | Not controlled |

| Velpatasvir | 1 | Not controlled |

| Vitamin B12 | 1 | Not controlled |

| Total | 199 | - |

-

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drugs Addiction. Accessed 09/04/2019. ↩

-

J.S. Li, Z.C. Li and M. Chen Analytical Chemistry Insight, 2012 7(7):47-58. ↩

-

MHRA warns athletes to avoid potentially dangerous DMAA. Accessed 10/04/2019. ↩

-

J.A. Morales-Garcia et al Scientific Reports: Nature (PDF, 7.06MB) (2017), 7:(5309). ↩

-

Q. Chen et al Int. J. Cancer (2004) 114 675-682. ↩

-

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drugs Addiction. Accessed 09/04/2019. ↩

-

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drugs Addiction. Accessed 09/04/2019. ↩

-

The World Anti-Doping Code International Standard: Prohibited List, January 2019 (PDF, 3.82MB). Accessed 11/04/2019. ↩

-

UN United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 1988. ↩

-

L. Rapport and B. Lockwood, The Pharmaceutical Journals (2000), 265. Accessed 10/04/2019. ↩

-

EDND - European Information System and Database on New Drugs. Accessed 12/04/2019. ↩

-

EDND - European Information System and Database on New Drugs. Accessed 12/04/2019. ↩

-

Annual Report of the Independent Monitoring Board at HMP Cardiff; for reporting Year 1 September 2016 – 31 August 2017, Published January 2018. Accessed 12/04/2019. ↩

-

Scottish Police Service News; Creating a Smoke Free Prison Environment. Accessed 12/04/2019. ↩

-

National Offender Management Service Annual Report and Accounts, 2016-2017. Accessed 12/04/2019. ↩

-

PHE North West Bulletin Issue 10, October 2017 (PDF, 964KB). Accessed 12/04/2019. ↩

-

Forensic Science Education, BINACA 030619 CFSRE report. Accessed 30/04/2019. ↩

-

EDND - European Information System and Database on New Drugs Accessed 15/03/2019. ↩