Theory based evaluation: Health-led Employment Trial Evaluation

Updated 8 April 2024

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

August 2022

DWP research report no.1037

A report of research carried out by the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit nationalarchives

or write to

The Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

or email [email protected]

This document/publication is also available on our website at: www.gov.uk

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email [email protected]

First published July 2023

ISBN 978-1-78659-549-2

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report is part of a series covering the implementation and outcomes of the Health-led Employment Trials (HLT). It explores how far the planned outcomes for the treatment group, health system and employers were achieved and the mechanisms and contexts which enabled or prevented these. The Theories of Change (ToCs) (Appendices 6.2 to 6.7) which were developed in the design phase of the trials to underpin delivery and evaluation form the basis for this exploration.

The analysis is based on interviews with recruits, trial staff, employers, partners and stakeholders.[footnote 1] It includes sections on the outcomes of the treatment group, health system, and employers achieved by Working Win (WW) in Sheffield City Region (SCR) [footnote 2] and Thrive into Work (TIW) in West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA). Each section identifies which major and intermediate outcomes were achieved suggests the contexts and mechanisms that enabled or prevented outcomes, and summarises the causal pathways based on qualitative research evidence. An analysis of management information (MI) covering the profile of recruits to the treatment group, the support, and outcomes is included in appendices 6.8 to 6.9.

The qualitative research showed some outcomes for the treatment group were achieved but there was little or no evidence of major outcomes for employers or health systems.

Evidence of major outcomes achieved for employment and health

The findings suggest that the assumptions outlined in the ToC for the treatment group broadly held true for the following outcomes:

- returning to work or getting a new job

- experiencing improved health and wellbeing

There was evidence that the treatment group, and the employment specialists leading their support, achieved major outcomes such as new jobs or improved wellbeing and attributed these to the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) services. Where major outcomes were not evidenced for individuals, the qualitative data suggested this could be due to them not being ready to work, having serious or multiple health conditions affecting their ability to work, or external factors such as lack of suitable jobs or difficult family circumstances. The form of IPS delivered in the trials could not overcome these barriers for all in the treatment group.

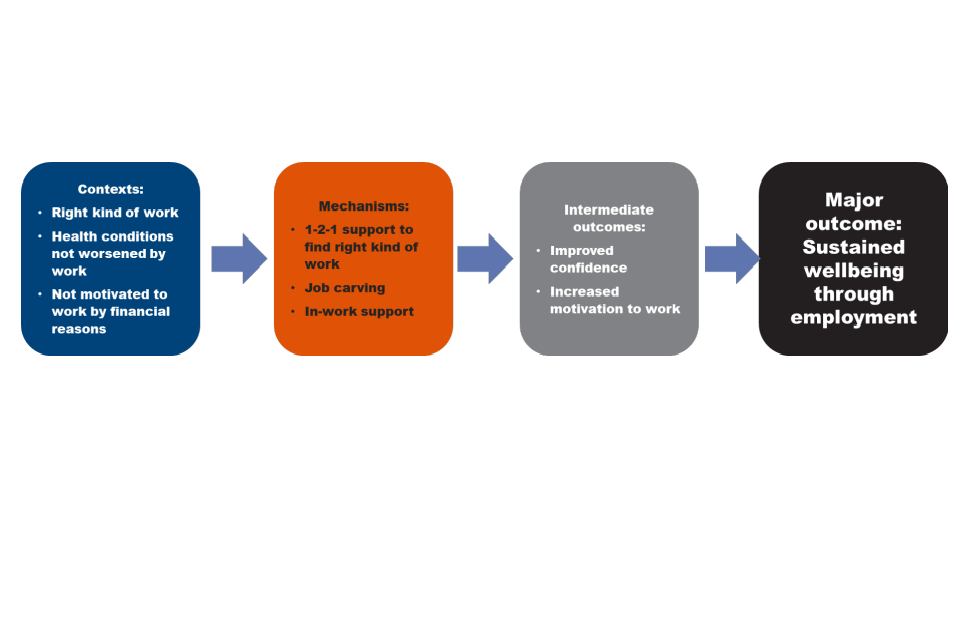

Limited evidence of major outcomes on work supporting health, and earnings

In contrast, findings suggest that the assumptions outlined in the ToC for the treatment group did not hold true for the following outcomes:

- experiencing work as a therapeutic outcome

- improved income

In order for the treatment group to experience work as a therapeutic outcome, three contexts needed to be in place. They needed to have the right kind of work, a health condition that was not exacerbated by working, and not be motivated to work purely by financial reasons. These contexts were not consistently observed in the qualitative research. Qualitative evidence on why the treatment group did not experience improved income was limited, but might be explained by some only being able to access lower quality work, or conversely, by some preferring to take part-time or lower paid work as this was better for their wellbeing.

Employer and health systems: Limited evidence of major outcomes

The findings suggest that the assumptions outlined in the ToCs for employers and health systems did not hold true for the following major outcomes:

-

Employers more willing and confident to take on and support disabled people and those with long-term health conditions, and to make use of external health-related support for employees.

-

Health partners would view conversations about employment with patients as a key part of their role, have a better understanding of the relationship between work and health, and see it as part of their role to make wider referrals including to employment services.

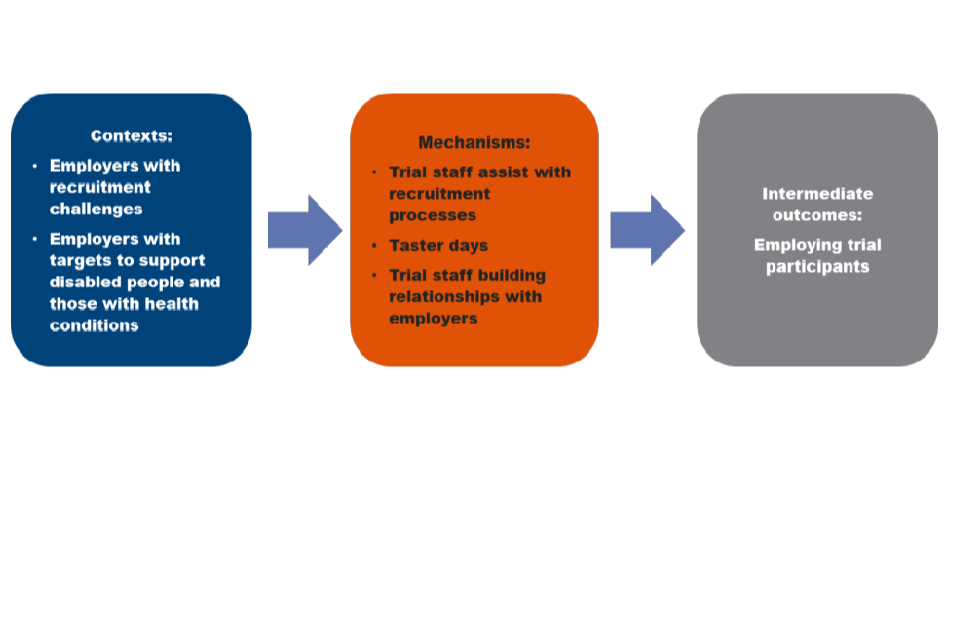

Health system and employer intermediate outcomes such as greater awareness of the trials were not consistently in place which in turn meant that major outcomes for these groups could not be achieved. There was evidence of individual trial staff engaging effectively with individual employers and health partners, but this was not systematically in place. If there had been more strategic engagement with employers and health partners it seems likely this would have led to greater change. These outcomes may also have needed more time than the trial allowed to be realised.

The limited success in employer and health systems engagement may also have affected the outcomes of some in the treatment group with more substantial needs, as well as the achievement of improved income and experiencing work as a therapeutic outcome.

The final report series for the trials covers:

-

Synthesis report: a high-level, strategic assessment of the achievements of the trial, drawing together the range of analyses from the evaluation.

-

4 month outcomes report covering: an analysis of implementation, a descriptive analysis of the survey findings 4 months post-randomisation, and an assessment of impact at 4 months following randomisation.

-

12 month survey report providing a descriptive analysis of the final survey, based on the theory of change for those in the treatment group.

-

Context mechanism outcome (CMO) report, reporting evidence on outcomes from the trials and relating these to its theories of change.

-

12 month impact report covering the net effect on employment, health and wellbeing resulting from the trials 12 months after randomisation drawing on administrative and survey data.

-

Economic evaluation report exploring the costs and benefits arising from trial delivery, drawing on the administrative and survey data.

-

The pandemic and the trial: an analysis of how the trial outcomes may have been affected by the onset of COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

Please see the synthesis report

Authors’ credits

Jess Elmore is a Research Manager at Learning and Work Institute (L&W). She managed part of the process evaluation. She is a qualitative researcher who has worked across a range of projects with a focus on disadvantaged or hard to reach groups and their access to education and employment.

Rosie Gloster is a Principal Research Fellow at IES. She supported the management of the evaluation consortium and contributed to the process evaluation. She is a mixed-methods researcher specialising in employment, and careers. She has authored several reports for the DWP, including the evaluation of Fit for Work.

Naomi Clayton is Deputy Director of Research and Development at L&W. She provided quality assurance for L&W’s contributions to the evaluation. She has specialisms in employment, skills and labour market disadvantage issues, and has worked with partners across the UK on multiple evaluations.

Becci Newton is Director of Public Policy and Research at IES and specialises in research on unemployment, inactivity, health, skills and labour market transitions. Becci has managed the evaluation since its design and contributed to the process evaluation. She has led multiple evaluations for DWP including of the 2015 ESA Reform Trials and the Work Programme.

Rebecca Duffy and Zoe Gallagher are Project Support Officers at IES and proofread and formatted the report.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Area | A defined, geographic area within a trial site |

| Baseline data collection | Data from the baseline assessment completed by provider staff who recruited people to the trial |

| Casual link | The connection between a cause and an effect |

| Casual pathway | A way to explore and understand the journey to outcomes, including the role of intermediates outcomes in the achievement of final outcomes |

| Clinical commissioning groups | Clinically-led statutory NHS bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of health care services for their local area |

| Deep dive | Thematic case studies used in the process and theory of change evaluation with methods varying depending on the selected themes for investigation |

| Descriptive analysis | Producing statistics that summarise and describe features of a dataset such as the mean, range and distribution of values for variables |

| Employment specialists | Staff employed by the trials to undertake randomisation appointments, provide IPS support to the treatment group, and undertake employer engagement |

| Final survey | The survey completed by recruits 12 months after randomisation |

| 4 month survey | The survey completed by trial recruits 4 months after starting the trial |

| Health-led employment trials | Two trials, funded by the Work and Health Unit, to test a new model of employment support for people with long term health conditions |

| Individual placement and support (IPS) | IPS is a voluntary employment programme that is well evidenced for supporting people with severe and enduring mental health needs in secondary care settings to find paid employment |

| IPS fidelity scale | A scale developed to measure the degree to which IPS interventions follow IPS principles and implement evidence-based practice |

| Provider staff | Those working in provider organisations including employment specialists delivering IPS support, as well as managers and administrators |

| Randomised controlled trial | A study to test the efficacy of a new intervention, in which recruits are randomly assigned to two groups: the intervention group receives the treatment, while the control group receives either nothing or the standard current treatment |

| Recruits | People who agreed to take part in the trials and who were randomised to either the treatment or control group |

| Refer / referral | A recommendation that an individual should be considered for the trial, facilitated by a means to directly connect them to a trial provider |

| Self refer / self referral | Individual applies for more information about the trial via the trial website or helpline and uses information there (phone number, web form, email) to make contact with the trial provider and request support |

| Signpost | Recommendation to an individual from a support organisation that they consider joining the trial, by providing them with information (leaflets, reference to website or helpline) leading potentially to the individual self-referring into the trial |

| Site | The trials were delivered in two combined authorities, which are termed sites |

| Survey | A research instrument used to collect data by asking scripted questions or using lists or other items to prompt responses. Can be conducted in person face-to-face, by telephone, or by postal or web-based questionnaire |

| Sustainability and transformation partnerships | A partnership of local NHS organisations and Councils which develop proposals for improved healthcare |

| Theory of change (ToC) | A description and illustration of how and why a desired change is expected to happen in a particular context. It sets out the planned major and intermediate outcomes and how these relate to one another causally |

| Thrive into work | The name given to the trial in WMCA |

| Trial Group(s) | Three trial groups are referred to in the report: two out-of-work (OOW) groups (one in each combined authority), an in-work (IW) group in Sheffield City Region (SCR). These groups are pooled as All OOW and All SCR in different elements of the analysis |

| Working win | The name given to the trial in SCR |

1. Introduction

The report presents the theory-based analysis of the outcomes and causal pathways from the evaluation of the HLTs in SCR and WMCA based on interviews with recruits, staff, employers, stakeholders, and partners. It considers how far intended outcomes were achieved for recruits, health systems, and employers, and interrogates the contexts and mechanisms that enabled these outcomes.

The analysis in this report is based on data collected as part of qualitative interviews with different groups, shown in Table 1.1 and deep dives shown in Table 1.2. The interviews were conducted at 3 points between September 2018 and March 2020, with additional employer, partner and system level interviews held later in 2020 and into 2021. The deep dives were conducted between December 2018 and March 2020, and each explored an aspect of the trials in detail.

Table 1.1 Completed interviews by site

| Respondent type | SCR interviews | WMCA interviews | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals: treatment group | 48 | 48 | 96 |

| Individuals: control group | 17 | 18 | 35 |

| Individuals: longitudinal | 34 | 32 | 66 |

| Staff | 34 | 36 | 70 |

| Stakeholders and partners | 17 | 15 | 32 |

| Employers | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Total interviews | 157 | 156 | 313 |

Source: Evaluation records

Table 1.2 Deep dives

| Theme of deep dive | SCR | WMCA |

|---|---|---|

| Employer engagement | Staff focus group and document review | Staff focus group and document review |

| Delivery of employment support | Treatment group, focus group and document review | 6 interviews with treatment group members and document review |

| Delivery of job development activities | 5 interviews with treatment group members and MI analysis | 5 interviews with treatment group members and MI analysis |

| Engagement of primary and community care | 3 interviews with partners and document review | Focus group with partners and document review |

Source: Evaluation records

The report uses the ToCs (Appendices 6.2 to 6.7) that underpinned the evaluation of the HLTs to explore how far the trial outcomes were achieved. It includes sections on the treatment group, health system, and employer outcomes as achieved by WW in the SCR and TIW in the WMCA. An analysis of management information, including the profile of the treatment group attached to each trial, the support delivered, and the outcomes achieved, is included in appendices 6.8 and 6.9. Each section identifies which major and intermediate outcomes were achieved from the evidence collected in the qualitative research, the contexts and mechanisms that enabled or prevented these outcomes and summarises the causal pathways.[footnote 3] The report indicates where there are apparent differences between the sites in terms of how effectively mechanisms worked to achieve outcomes. These comparisons are necessarily tentative due to the significant differences in context, implementation and reporting between the sites.

Further details about the implementation and delivery of the trials based on the process evaluation data are available in the implementation and 4 month outcomes report. It contains information about the providers, the trial sites, and the recruits to treatment and control groups. It also highlights lessons learned from delivery. Quantitative data covering outcomes is available in the 12 month impact report which covers the net effect of the trials on employment, health and wellbeing 12 months after randomisation. The experience and outcomes of recruits to the treatment and control groups is covered by the 12 month survey report which provides a descriptive analysis of the final survey.

2. Outcomes in the treatment group

2.1 Introduction

This section explores the major outcomes experienced by the treatment group. These were reported during the interviews with individuals and trial staff, and are mapped to those predicted in the ToCs (Appendices 6.2 and 6.3).

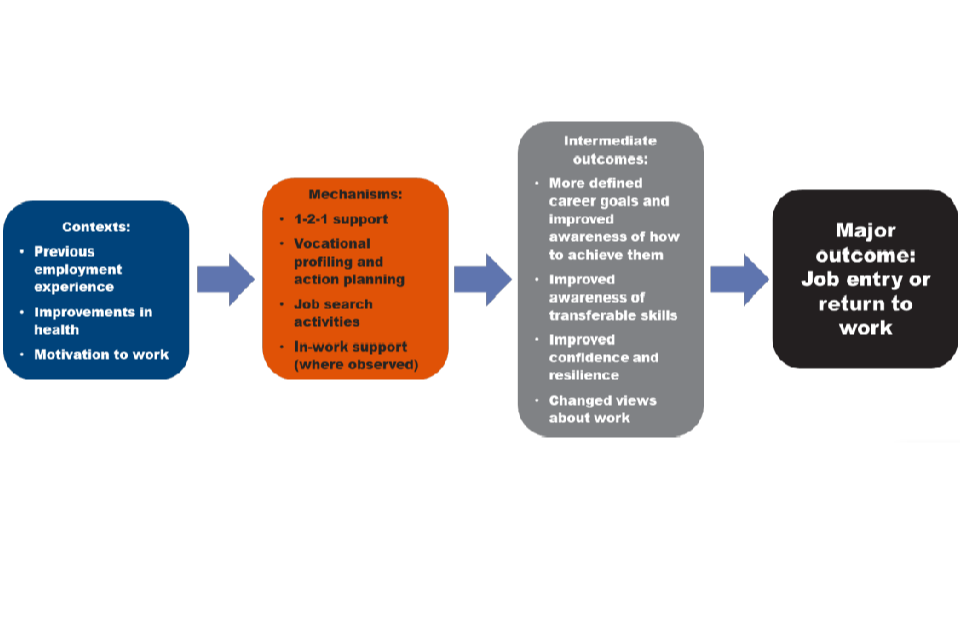

The section considers the following causal pathways[footnote 4] through which the HLTs were designed influence outcomes as predicted by the ToC. Causal pathways 1,2 and 3 are relevant to all recruits to the treatment group, namely: WMCA OOW group, SCR OOW group and SCR IW group, while causal pathway 2a is relevant only to the SCR IW group.

-

Causal pathway 1: The trial will increase or sustain the income of the treatment group, through them entering and sustaining employment. This will be supported through the employment specialist achieving the best possible job match for the individual based on their skills and interests, which in turn will result in satisfaction in work and thus support work sustainment. Achieving and sustaining employment will also lead to reduced benefit receipt.

-

Causal pathway 2: Through being in work, and as a result of the receipt of the IPS services members of the treatment group will improve their health (physical and mental) and make more effective use of health services, thereby reducing the costs on health services in the long run.

-

Causal pathway 2a (SCR in-work): Those in work will also be more productive in work, leading to less time off due to ill health (than the control group), with less reliance on statutory and employer sickness support.

-

Causal pathway 3: As a consequence of improved health, income and good quality employment, the treatment group will also see their wellbeing improved. The analysis focuses on the contextual factors and mechanisms that contribute to outcomes in relation to: returning to work or getting a new job, experiencing improved health and wellbeing, and experiencing work as a therapeutic outcome.

2.2 New job and return to work

Contexts

At the time of the final survey (12 months after recruits were randomised into the trial), 35% of the treatment group were either in full or part-time work. This section first identifies the contexts that enabled or prevented this major outcome and then considers how these interact with mechanisms and intermediate outcomes.

Contextual factors enabled and prevented the treatment group from starting or returning to work.

For those interviewees in the treatment group who successfully found or returned to work the enabling factors included their previous experience of employment (in some cases within specific sectors of interest), improvements in health since randomisation, and increased motivation to find work for financial and personal reasons. Contextual factors which created barriers to entry into work included ongoing health and wellbeing factors, employer attitudes, individual employment objectives, the availability of suitable opportunities, levels of confidence and motivation, and external factors such as travel and childcare issues.

Previous recent experience of employment was a key contextual factor influencing the treatment group’s entry into new jobs.

OOW interviewees who entered new jobs were more likely to have been in stable employment prior to the onset of their health conditions, although others had been out of work for a number of years. Trial staff also noted that it could be easier to place those who had a recent employment history. Where the treatment group had experience in the particular sector they wanted to find work in, they had a better understanding of their skills and preferences, and this helped to focus their job search activities on areas of interest to them. By contrast, some with high level skills or specialist training reported that they had been unable to find work in their specialist area, or no longer felt able to work in these areas due to their health. These interviewees from the treatment group were more likely to be dissatisfied with the job advice and support offered by their employment specialists, which they said was too generic and overly focused on basic skills to be useful to them.

Across both sites, improvement in health for the treatment group was seen as a key contextual factor in supporting entry to work.

This could include improved management and understanding of health conditions as well as improvements in overall health. In the qualitative research, recruits in the treatment group and employment specialists believed improvements in health meant the treatment group were: better able to focus on applying for work, more confident they would be successful, and more able to work in their new role without exacerbating their health conditions. These improvements were sometimes attributed to support received within the trials, to support from the NHS and other organisations or changes in medication. However, improvement in health is a major trial outcome as well as a context, and this is discussed in section 1.2.2.

Improvement in health was particularly discussed as a key factor in supporting entry into a new job or a return to work for the SCR IW group. For example, a member of the treatment group who entered work reported they had improved the management of their condition as a result of support from their employment specialist, including health support to get on effective medications. The change in medication meant they were more comfortable going back to work. This suggests that health was a greater focus of support received for the IW group and may in part explain the findings from the impact report that the IW group experienced the most significant improvements in their health and wellbeing.

Severe health conditions or difficult personal circumstances were contexts that prevented the treatment group entering employment.

As detailed in the implementation and 4 month outcomes report (section 2.2,3 and 3.2.1), some interviewees in the treatment group had been told by other health professionals that they were not ready to work, and this context meant employment outcomes could not be achieved. In this way, employment specialists identified cases where they were not able to follow IPS principles and progress the treatment group rapidly towards employment. The longitudinal interviews with the treatment group gave an insight into health over time. Where their health was already improving as they entered the trials they could move towards employment, but those with degenerative or relapsing conditions were less able to benefit from support to find work. There could also be setbacks. For example, one of the treatment group interviewees described in the first interview how support from their employment specialist had led to them increasing their working hours. However, at the time of the second interview their worsening health had led them to reduce their working hours again.

A few taking part in the treatment group interviews had been unable to find work due to their personal circumstances, for example, needing a job with specific hours due to family and caring responsibilities, or needing a job which was close to their home to enable an accessible and affordable commute. Others had wider issues to address that they felt were more immediately important than employment, such as finding housing after experiences of eviction and homelessness. When employment specialists were engaged in resolving issues such as homelessness, they were not able to rapidly progress the treatment group to employment. If job brokerage and carving[footnote 5] had been more in evidence, then individuals with personal circumstances such as requiring reduced hours may have been more likely to progress to employment.

It was important that the treatment group was motivated to enter work, a key principle of IPS.

This was often connected with a feeling that it was the right time as their health condition was no longer preventing them working. Employment specialists also discussed the importance of motivation, and felt that the treatment group needed to be motivated to look for work to achieve positive employment outcomes. Motivation is a context as well as an intermediate outcome of the intervention. It is important to note that motivation fluctuated over time although the support delivered nonetheless was expected to improve the treatment group’s motivation overall. Employment specialists generally felt that engagement with the IPS services meant that motivation to work increased and this is reflected in the survey findings (section 7.4 of the 12 month survey report).

Where members of the treatment group taking part in the qualitative research did not know what job role they wanted to do, they appeared less likely to enter employment.

This could include individuals who had experienced lengthy periods of unemployment, had previously held a number of low-skilled jobs or a combination of both. Employment specialists also reported that some in the treatment group had unrealistic ideas about the work they could do, and this made it less likely for them to find work. However, this was a less significant context. In the qualitative research, interviewees in the treatment group who had not entered work as a result of the trials were relatively clear about their future aspirations, and were still in the process of making applications and identifying opportunities.

Employment specialists found that ongoing low levels of confidence in the treatment group prevented entry to work.

This context was not observed frequently within the qualitative research. It generally occurred where a treatment group member had been out of work for a long time, had a severe health condition, or had a lack of awareness of their skills and was also dissatisfied with the support they received. For these, support from their employment specialist did not improve their confidence. Potential factors included the rapid progression to job search which increased anxiety levels for some, communication problems with their employment specialist, or the time-limited nature of the support which meant there was not time to address their barriers.

A lack of skills, qualifications or experience were contexts that prevented the treatment group from entering work.

Employment specialists, particularly in WMCA, framed this in terms of recruits’ starting point on their employment journey at the outset of the trial. They indicated that those in the treatment group with longer durations of unemployment were more challenging to place.

For some in the treatment group there were specific issues, for example a criminal record, not holding a driving licence, or needing a particular vocational qualification for a sector such as childcare that prevented them finding work. In other instances, these barriers were removed. For example, an employment specialist supported an individual in the treatment group to reapply for their driving licence. However, this depended on the eligibility of the individual for funding for additional qualifications.

Skills development was not included as a mechanism or outcome within the ToCs, and there was little evidence of ‘place then train’ in the qualitative research.

The availability of suitable work was an important context that had several dimensions.

Firstly, whether jobs were available in the sectors that the treatment group were interested in, secondly, whether the jobs had good pay and conditions, and finally whether jobs were available to the treatment group given their health conditions and circumstances. Employer engagement activities should have helped to ensure that suitable jobs were available but, as discussed in section 1.4, their effectiveness appeared limited. It is, however, important to recognise that the availability of suitable work is an outcome as well as a context.

Employment specialists discussed the importance of opportunity in local areas to support people into the jobs they were interested in. This was particularly important as they wanted to work in accordance with the IPS Fidelity Scale.

But if they’re genuinely just interested in one thing and I’m trying to widen it because I can’t find anything that’s specific to what they actually want, I feel a bit barred and like I’m not doing IPS.

SCR employment specialist

Employment specialists noted a lack of suitable opportunities available, due to fluctuations in the labour market. In SCR particularly employment specialists felt that many roles were low quality, seasonal, zero-hour, or temporary contracts which might exacerbate health issues and prevent treatment group members from seeking other opportunities. Similarly, WMCA employment specialists discussed the need for employment opportunities to be of good quality and affordable for people wanting to leave the benefits system.

Interviewees from the treatment group also noted that competitiveness in the job market and a lack of suitable opportunities was a barrier to entering work, either due to their sector of interest, the preferred location of work, or contract types. In addition, when discussing the limited availability of jobs which offered preferable contractual arrangements, some indicated it was not sufficiently financially beneficial to move into work if this was on a part-time or temporary basis. There were also some who felt that they were unable to find an employer who would accommodate their health conditions. Those with more severe or degenerative health conditions were more likely to see this as a barrier to them finding employment.

Other interviewees in the treatment group felt their age limited their employment opportunities. They believed that they were getting to an age where employers would not consider them, or that their age might prevent them from accessing opportunities they would like such as apprenticeships, or opportunities to set up their own business. This may indicate that receiving treatment did not overcome them seeing their age as a barrier.

Those treatment group members who described in interviews that age or their health conditions prevented them finding work often experienced other barriers. One with a visual impairment needed more support to make applications as well as feeling that employers did not want to accommodate their needs. Another who felt their age and weight prevented them finding employment also did not have a clear idea about what job they wanted to do. This may indicate that those in the treatment group with multiple barriers were less able to benefit from support mechanisms.

Intermediate outcomes

The major outcome of a new job or a return to work was supported by a series of intermediate outcomes.

These in turn were facilitated by the mechanisms of different features of IPS. The IPS service was intended to lead to a series of intermediate outcomes such as increased confidence and motivation to work, and better understanding of skills and career goals which in some cases then led to work.[footnote 6] The relationship between features of support and outcomes was not always clearly defined. Some in the treatment group were not able to distinguish different aspects of support and attributed change more generally to having a good relationship with their employment specialist. Where employment outcomes were not achieved, a number of intermediate outcomes were still observed for those within the qualitative research, most notably improved confidence and motivation, or a change in their views about work and their condition as a result of the support they had received from their employment specialist. Section 4.8 of the implementation and 4 month outcome report includes a discussion of intermediate outcomes as reported in the survey findings.

Interviewees in the treatment group who had not yet found work were mostly still motivated to keep looking, although some still had concerns about the attitudes of employers to people with health issues as well as a lack of appropriate jobs in their local areas. Some in WMCA were demotivated as they did not think the support from the employment specialist had met their needs, which accords with the survey findings (section 7.1 in the 12 month survey report) where overall the treatment group in WMCA was slightly less satisfied than that in SCR with the support received by their employment specialist, and slightly less likely to feel that their employment specialist understood their needs.

Mechanisms

Mechanisms identified as leading to intermediate outcomes were vocational profiling and action planning, job seeking, a positive one-to-one relationship with their employment specialist, and in-work support. However, not all interviewees in the treatment group who achieved intermediate outcomes also achieved the major outcome of finding work.

Vocational profiling and action planning (planned mechanisms) contributed to intermediate outcomes of more defined career goals, an improved awareness of how to achieve them, and an improved awareness of transferable skills.

This was due to the treatment group having the opportunity to discuss possible options, their concerns, and preferences with their employment specialist. These discussions helped to identify what work was available and realistic, as well options that were of interest to them and would not exacerbate any health conditions. Employment specialists identified that observing the IPS principle that client preferences for employment should be understood and honoured meant they were more likely to be able to support individuals into work due to using these mechanisms.

You’re starting off with a much better understanding of what the individual wants and you’re being driven by what you’ve learnt from them, about them.

WMCA employment specialist

One interviewee in the treatment group reported increased awareness of their transferable skills as a result of updating their CV with their employment specialist, who had asked pertinent questions to help draw out the wider skills they possessed. This process led to a discussion of a wider range of job options and to the interviewee choosing work based on this new understanding of their skills. They noted that support from their employment specialist enabled them to identify and apply for different roles they had not thought of previously which were suited to them and their health condition. These mechanisms effected job outcomes for interviewees with a range of different health conditions, different employment histories and different ages. However, those with more severe health conditions or challenging personal circumstances, such as homelessness or problems with alcohol, were less likely to experience both these intermediate outcomes and major outcomes. As discussed in section 2.3.2 of the implementation and 4 month outcomes report the rapid move to action planning for employment was challenging for these latter groups and may have meant support was less effective for them.

The importance of specific job seeking activities (planned mechanism) varied for interviewees in the treatment group.

Activities such as CV writing, job searches, interview skills, and employment specialists contacting employers on behalf of the treatment group were pathways to employment in some cases. Others in the treatment group found work through their own contacts, after being prompted by employment specialists to use these. As detailed in sections 2.3.2 and 3.3.5 in the implementation and 4 month outcomes report job seeking activities tended to be more focused on basic activities such as internet searches rather than the employment specialist accessing hidden jobs or job carving. Interviewees in the treatment group with a higher level of skills (for example a degree) or a more professional work history (for example they had previously worked in a job which had specific vocational entry criteria) were less likely to report this mechanism leading to employment. Support with job seeking activities did not provide any additionality for these as they already had these skills.

One-to-one support from an employment specialist was a key planned mechanism for achieving employment outcomes as it helped to build resilience and confidence in the treatment group, increasing their motivation to work, and changing their views about work.

This was an effective mechanism for treatment group members with varying work histories and skill levels. However, those with more severe health conditions were less likely to report changes in their views about work while those with low level mental health needs were particularly likely to report changes in confidence. Interviewees in the treatment group reported a change in their views about work brought about by their interactions with their employment specialists. Those in the SCR IW noted that their employment specialist had helped them change their perceptions about what was possible for them in terms of work. They felt without these intermediate outcomes they would not have been as motivated or able to identify, apply for, and be successful with their new roles. One WMCA treatment group member who had entered a new job found that the support from their employment specialist had changed their attitudes to work by encouraging them to think about what jobs were suitable for their needs. This support was particularly helpful for those who had previously thought they would not be able to work again or felt employers may prefer to hire people who did not have health conditions.

That’s something that I really work on because I think that is the difference, a massive difference between people that go out there and really try and that can be resilient… and there’s other people that would say, “Well, there’s no point” if they didn’t get it, or didn’t get the last two “so I’m not going to try again, it’s too painful.

SCR employment specialist

Trial staff identified a causal pathway where mentoring led to improved confidence and motivation followed by further steps towards employment. For example, making more applications, and the treatment group presenting themselves effectively at job interviews. It should be noted though that the extent to which interviewees in the treatment group felt increased confidence had directly led to their entry into work was mixed. Some were unclear about the exact impact it had, and others believed improvements in their health had been more influential than increased confidence.

In-work support was an important planned mechanism for sustaining employment, where it was observed.

There was limited evidence of this mechanism within the qualitative research, and it was mentioned predominantly by interviewees in the SCR IW treatment group. Employment specialists reported that they encouraged disclosure of health conditions, and advised the treatment group about their employment rights and the financial support that they could access as well helping with form-filling. This included an employment specialist directly engaging with an employer to help on disclosure and negotiate improved working arrangements. Few interviewees however reported this. One had experienced a relapse in their physical health issues while employed, and their employment specialist set up a meeting with their line manager to negotiate adjustments which were then taken forward. This support was possible as the interviewee was comfortable discussing their health condition with their employer. Another interviewee found having the employment specialist contact and support them in their workplace helped them to stay in work and consider other options and support available depending on their goals.

MI data from SCR suggests that this mechanism was not in place for the majority of the treatment group who were in or entered work. Employment specialists recorded discussing reasonable adjustments and job brokerage with 19% and 15% of the treatment group, respectively.[footnote 7] However, while the MI data is suggestive of limited in work support, it is important to note that this data does not capture all instances of support. In this way it can be assumed that informal in work support was included in regular catch ups with treatment group members but not formally recorded.

The mechanisms discussed above did not work in all contexts.

Limitations in support (discussed in more detail in sections 2.3 and 3.3 of the implementation and 4 month outcome report) interacted with context. These limitations included:

-

Communication barriers between employment specialists and the treatment group:

In SCR this meant, in a few instances, interviewees had a lack of clarity about the nature of the IPS service and what its purpose was. In WMCA a few had not heard from their employment specialist as frequently as they felt they needed or did not think they understood their needs sufficiently. These were typically interviewees with more severe health conditions or health conditions which affected memory or cognition, as well as an individuals with English as an additional language.

-

Limitations in the support that was received:

In SCR, a small number of interviewees noted that they had difficulties completing forms and applications, and may have benefited from more frequent support, rather than weekly or fortnightly appointments. In WMCA a small number felt the employment specialist had not engaged sufficiently with prospective employers on their behalf, and others would have liked additional help with their CVs. More highly qualified interviewees could find activities such as CV writing of limited use, and some were disappointed that employment specialists were not giving them access to ‘hidden jobs’. This may suggest that the IPS service could have been more tailored to individual needs.

For interviewees in the treatment group with more severe health conditions, time limited support was a factor in preventing intermediate outcomes leading to work. Anxiety about the support ending emerged amongst those who had not secured an employment outcome. There were also instances where interviewees who had found employment at the time of their first research interview had not sustained this in subsequent research interviews and had used up their entitlement to IPS. This meant that they had experienced difficulties either after their entitlement to 4 months in work support had ended (OOW group) or after their 12 months of support had ended (IW group). Some of these interviewees felt their lack of access to further support meant they were less likely to secure new employment.

The limitations to employer engagement discussed in sections 2.3.5 and 3.4.5 of the implementation and 4 month outcome report also prevented progression towards employment. In this way the context of a lack of suitable vacancies can be attributed at least in part to employment specialists not being successful in finding hidden jobs and job carving.

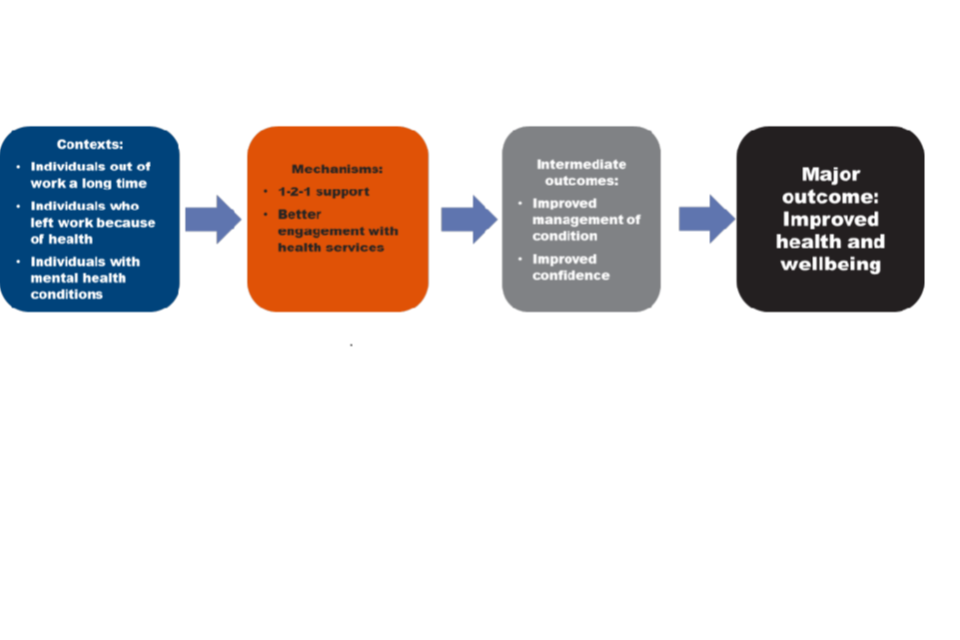

2.3 Improved health and wellbeing

Interviewees from the treatment group discussed improvements in their health and wellbeing as a result of the support they had received. Improved wellbeing was variously described in terms of being more active, having a more positive attitude both generally and towards work, engaging better with health services, and growing more resilient emotionally.

Contexts

The qualitative research showed that interviewees in the treatment group who experienced improved wellbeing had typically either spent a significant amount of time out of work, had been in a variety of short-term roles, had left their previous role due to their health condition, or for SCR IW group, had been unhappy in their current job. Most had depression, stress, anxiety, or other mental health issues.

Interviewees in the treatment group attributed improved health and wellbeing to the trials, although support received elsewhere was also a significant factor. This included counselling, therapy, online mindfulness videos, going to the doctor to receive medication, and better management of their health conditions. Section 7.1 of the final survey report suggests 67% of the treatment group found the support they received beneficial for their health, with SCR IW group most likely to find the support helpful and the WMCA group least likely.

Intermediate outcomes

Improved management of health conditions and improved confidence and motivation were the most common intermediate outcomes for improved wellbeing.

One interviewee felt their employment specialist had given them the skills, confidence, and ability to ‘turn my mental wellbeing around and head it off in a much more positive direction’. In turn, the job they found had enabled them to develop their skills and confidence further. Where interviewees reported improved management of their condition, but that this had not led to improved wellbeing, they were typically still adjusting to changes in confidence as a result of their improved condition management and any changes in work. Where interviewees reported improved confidence and motivation, but it had not led to improved wellbeing or other outcomes, this was typically because they: reported a less positive experience with their employment specialist, had not been able to find suitable work, or their health condition was having an impact on their quality of life.

Mechanisms

The key mechanism to the treatment group’s improved wellbeing was the one-to-one support from their employment specialist, leading to increased confidence and motivation (planned mechanism).

Some interviewees said this was because their employment specialist was a trustworthy person they could talk to about their problems. Those in SCR also described wider factors which contributed to their improved wellbeing, including support to improve their financial management and debt situations, and learning how to balance work-related activity with their health condition. When employment specialists discussed the treatment group achieving health outcomes, they reported building confidence and self esteem as crucial to improving wellbeing.

Better engagement with health services was another mechanism that the treatment group felt had improved their wellbeing (planned mechanism).

The employment specialists’ encouragement to engage with health professionals and follow medical advice meant the treatment group were better able to manage their health conditions. For example, one employment specialist had referred an individual to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services to support their in-work wellbeing as well as worked with them to disclose information to their employer.

That has been really successful in just getting them some basic support with the anxiety the depression the panic attack and that’s actually meant that they are stayed in work they’re feeling a lot happier at work and it’s also resulted me going in and speaking to the employers as well with the customer’s sort of consent and explaining about the services that we can offer and so the employer realises that the customer is getting the support and actually its very beneficial and that they’re actually doing a better job and they’re more content to stay there and that’s obviously giving sort of a service a really good reputation as well

SCR employment specialist

The importance of making new links with GPs and other NHS services to understand the treatment group’s needs and provide support for them was also identified as an important mechanism for improving wellbeing by employment specialists. However, the limited evidence of case conferencing[footnote 8] as a mechanism meant that not all in the treatment group benefited from these links. Interviewees in the treatment group with more serious health conditions or multi-morbidities talked about the support they received from different agencies although their employment specialists did not have a role in coordinating this support.

Finally, some interviewees in the treatment group identified that entering work or starting volunteering had improved their wellbeing (planned mechanism).

This is discussed in the following section.

2.4 Work as therapeutic outcome

The exploration of work as a therapeutic outcome was limited to those interviewees in the treatment group who reported finding new jobs, returning to work, or increasing participation in work, as well as discussions of what enabled work as a therapeutic outcome with employment specialists. There were three dimensions to work being seen as a therapeutic outcome. Firstly, the treatment group experienced improvements in their health and wellbeing as a direct result of being in work. This typically meant improved confidence and mental wellbeing. Second, the financial benefits of work led to improved health and reductions in stress and anxiety. Finally, the right kind of work meant the treatment group experienced improved wellbeing because they had new opportunities to use their skills and progress in their careers.

Contexts

In combination, the qualitative findings indicated that for the treatment group to experience work as a therapeutic outcome, they needed to have a job that was right for them, a health condition that was not exacerbated by working, and not be motivated to work only for financial reasons.

Work could not be a therapeutic outcome without these contexts. Some in the treatment group, particularly those with more serious or degenerative health conditions, found that work had negative impacts on their health. It was particularly common for the SCR IW group interviewees to report that their health difficulties had been exacerbated by their previous work roles, or that they were unhappy in their work. This was often linked to feeling they had to work for financial reasons even if the work was not suitable for their health. Some interviewees discussed feeling pressured to return to work as a result of reduction in their sick pay, which meant they could not cover their living costs.

Where the treatment group could not find the right kind of work, they were less likely to experience improved wellbeing. This could be because they had entered work that might not have been in their preferred sector or factors such as a long commute or unsuitable hours also made working more difficult. Conversely, when the right kind of work was available, and their health allowed them to experience the benefits of work, there were several key mechanisms and intermediate outcomes that meant the treatment group experienced the therapeutic benefits of work.

Mechanisms

The planned mechanism of one-to-one support leading to increased confidence was important if the treatment group were to find working a positive experience.

Employment specialists emphasised the importance of improved confidence and increased motivation and aspiration to work as this helped change attitudes and meant that the treatment group viewed work as something they could both do and benefit from.

Interviewees discussed their entry into work or improved working conditions as helping to maintain their improved confidence following their engagement with the trial.

Support to find the right kind of work which could then benefit their health and wellbeing (planned mechanism).

Interviewees in the treatment group described how taking part in the trials had enabled them to find jobs they were interested in and passionate about, and that would also support their health needs. One described how their employment specialist had facilitated them getting a job in an organisation which they knew was supportive of wellbeing and where they could take professional qualifications to advance in their career. Another was supported to retrain as a teaching assistant. This came with a loss of income but with a rise in job satisfaction and an increase in wellbeing.

Job carving and ongoing in-work support were important planned mechanisms when observed, although there was limited evidence of them within the qualitative research.

Employment specialists discussed the importance of ongoing in-work support for mental and physical health to enable the treatment group to maintain the benefits of being in work. However, they noted their ability to offer this support was limited where individuals were not willing for their health conditions to be disclosed and as such had worked with them to help them understand and feel comfortable to do this. A few employment specialists also discussed the importance of job carving to help make the experience of work more manageable in relation to individuals’ health. An SCR IW treatment group interviewee described how their employment specialist had helped them negotiate their return to work with reduced management responsibilities leading to improved health and reduced stress. In contrast, another reported their increased confidence had resulted from discussions with their employment specialist that meant they had taken on additional management responsibilities at work.

Employment specialists were still able to provide beneficial in-work support in cases where the treatment group did not want to disclose their health conditions or needs. This was primarily because the treatment group were better equipped to understand the working conditions that would best suit them and manage their conditions at work through more general conversations with their employment specialist about work. This meant that some in the treatment group who found entry into work came with risks for their health (for example, additional stress) had found ways to manage and balance it with the benefits of being in work. In one example, an interviewee found the long commute to their workplace did not support their wellbeing, but felt better to be working in general. Another discussed the importance of entering an agency role which the found less stressful than a permanent contract because they were better able to control when they were working and were able to protect their health this way.

Engagement with employers and healthcare organisations were not consistently observed as mechanisms leading to work as a therapeutic outcome (planned mechanisms).

Some SCR employment specialists felt that more work could have been done in terms of employer engagement and marketing the service to employers so that they may better understand the benefits of improved health to their workforce, and the impact this could have on their business. Nonetheless, one SCR employment specialist described helping reduce attrition in some large companies by working with them on their approach to the health of their employees. In contrast, employment specialists in WMCA felt that GP engagement was more important, to tackle traditional ideas of the role of work in patient recovery, which limited their engagement and referrals to the trial. The limitations of engagement with employers and healthcare organisations are discussed in sections 1.3 and 1.4.

2.5 Summary of causal pathways

Overall, the main outcomes achieved by the treatment group as captured within the qualitative research were related to employment, either through entering or sustaining work, with one-to-one support as the key mechanism. This meant that the treatment group gained the confidence and motivation to find work which emerged through vocational profiling and needs assessment, and activities to find and prepare for entering work. Entry to work was, in some cases, further supported through improvements in individuals’ health.

Where SCR treatment group interviewees reported no intermediate outcomes, the qualitative research indicated an interrelationship with combinations of the severity of health issues and some limitations in the support. Where WMCA interviewees saw limited or no intermediate outcomes there was an interrelationship with significant breakdowns in communication with their employment specialist. However, some of the interviewees who reported limitations in the IPS support also had significant barriers, either communication or health difficulties that had an impact on their ability to engage with support. Findings from the survey (section 7.4 of the 12 month outcomes survey report) show that those with better health and higher mental wellbeing were more likely to have more positive views of the support, and to perceive it had helped them find employment.

In the qualitative research, health and wellbeing benefits emerged for the treatment group a result of encouragement from their employment specialists and others to improve management of their condition, increase their motivation and confidence, and support the sustainment of work through the discussion of reasonable adjustments. These were more evident within the SCR IW group. There was very limited evidence within the qualitative research of the treatment group experiencing increased income as a result of a new job or a return to work. This is consistent with the findings of the 12 month impact report where the trials were not found to have any impact on earnings.

In some instances, initial challenges in engaging with employers and health organisations (as observed in the implementation and 4 month outcomes report, sections 2.2.1, 2.2.5, 3.2.1 and 3.2.5) may have limited improvements in health and wellbeing in the treatment group, and had implications in respect of the limited evidence for therapeutic benefits of sustained work.

Health systems outcomes

3.1 Introduction

This section considers the health systems causal pathway which includes the following major outcomes:

-

that health professionals view conversations about employment with patients as a key part of their role

-

that health professionals have a better understanding of the relationship between work and health and recognise the therapeutic value of work

-

that health professionals see it as part of their role to make wider referrals outside of the NHS, including to employment services.

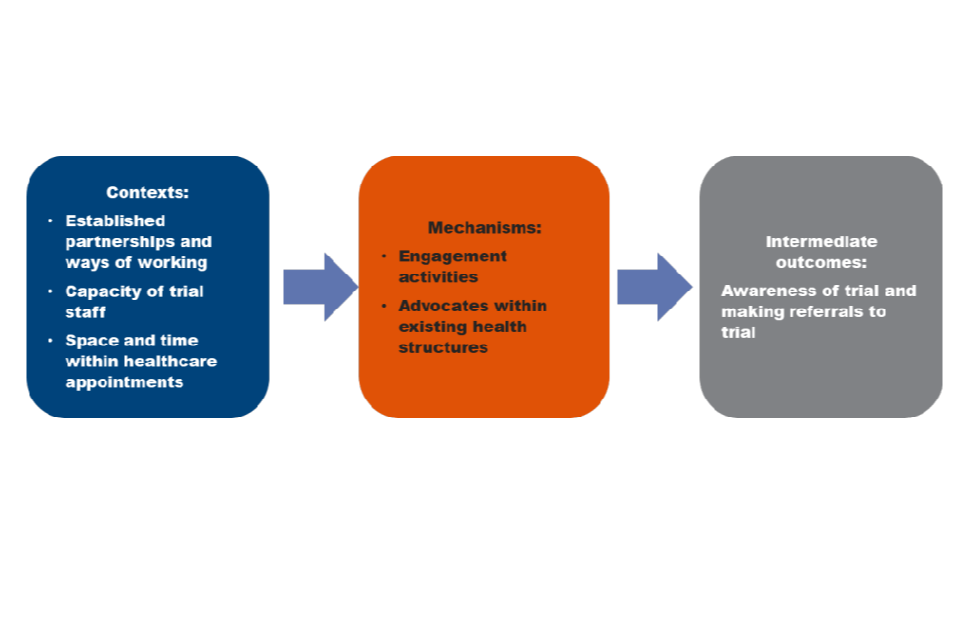

The trials were designed to effect change within health systems and on health professionals’ behaviour to better integrate work and health services and support for patients (Appendices 6.4 and 6.5). Health system change was anticipated to support outcomes, and to be a valuable outcome for the local areas. The health systems ToC predicted that the trials would achieve change by first creating awareness amongst healthcare services and generating referrals to the IPS services, and then promoting effective partnership working between health teams. This would then lead to major outcomes: that healthcare professionals would value IPS and discuss employment options with patients, conversations about employment between health professional and patients would be normalised, and appropriate referrals to support would be made.

Beyond the lifetime of the trials, it was anticipated that this change would lead to longer term outcomes: more effective use of Fit Notes among GPs, and health professionals referring to non-NHS services alongside any health referrals, with the continued integration of work and health prioritised through the Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships.

During the trials’ design and delivery, some contextual factors affected ways of working, delivery mechanisms and ultimately their ability to realise the ambition to contribute to widespread health system change. Health systems are complex, with several layers. The trials’ development coincided with wholesale changes to health system structures to support integration and public sector reform. Primary Care Networks (PCNs) were being established and new legal entities created. The trial in SCR was commissioned via the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), and representatives from the CCGs and Integrated Care System (ICS) sat on the steering group. This supported South Yorkshire Housing Associations (SYHA) (the IPS provider) to build links and access healthcare settings, and the strategic level engagement and integration was complemented by direct communications to healthcare staff. In WMCA, a CCG also led the commissioning process. While awareness raising activity to encourage health referrals was led by the primary care engagement lead, supported by ongoing engagement undertaken by the providers, there was less health system involvement in management and governance structures in WMCA (as detailed in section 1.3.1 of the synthesis) report. In WMCA, , the health sector was not as systematically or routinely engaged in the trial design and set-up. This was led by a contracted organisation (Social Finance) rather than local partners as in SCR. Structural issues also affected ease of health sector engagement in WMCA as health services were not part of the remit of the Combined Authority (see the synthesis report).This may help to explain the evidence from the impact report that the SCR trial had a positive impact on health and well-being while the WMCA trial did not.

The following section is based on interviews with staff, stakeholders, and partner organisations. Each planned mechanism of the health system ToC is tested against the evidence gathered in the evaluation to understand how far it operated within the trials and the context which supported or inhibited the planned change to occur.

Awareness of the trials and referrals made

The engagement of health practitioners in referring patients to trials in SCR and WMCA underpinned health system change (planned mechanism).

It was anticipated this mechanism would build health practitioners’ understanding of the influence of employment on health. To enable this change, primary care and community healthcare services were intended to be the main referral sources to the trials. However, in practice, this was not fully or consistently realised. Self-referrals and referrals from other sources were most common, accounting for more than half the referrals in both trial sites. Nevertheless, SCR recorded more direct referrals from health settings (42%, with 18% from a GP, and 24% from specialist care service), than WMCA where 20% of referrals came directly from health service providers (16% from a GP, and 4% from a specialist care service). Local factors help to explain these differences and shed light on the contexts and factors that enabled this change mechanism in healthcare settings.

In both sites it was challenging to get agreement and commitment to refer patients across layers and parts of the healthcare system within the trial design timescales.

In SCR, engagement with health partners during the design phase was more wide-ranging and comprehensive than in WMCA. It was enabled by more established partnership working between employment and health services, good links with social prescribing and IAPT services, and involvement from senior managers in the health system. These structures meant trial staff were better able to undertake successful initial engagement with referral agencies, and to negotiate with gatekeeping organisations. For example, in SCR, an employment specialist noted they first met senior managers within an Orthopaedics Outpatient department, before then being able to engage with all healthcare staff in that setting. Other employment specialists in SCR discussed regularly attending IAPT team meetings.

The design stage underestimated the amount of time required to systematically engage GPs and other parts of the health system and to consider their varying capacity and motivation to engage.

Staff reported there was insufficient activity with health providers and GPs to build initial awareness and engagement and believed more intensive relationship building and contact over a longer lead-in time was needed to gain the number of referrals originally anticipated from GPs (see implementation and four-month outcome report section 2.2.1 and 3.2.1). Delay to the anticipated trial start date, pending approval by the Health Research Authority (HRA), was also reported to have made engaging with health services more challenging.

Advocates within existing health structures were important to encourage referrals (unplanned mechanism).

Leaders such as public health champions or GP leads were noted as being influential advocates for the trials and supported engagement from other health professionals. The existing effectiveness and maturity of health partnerships, and support they could offer the trials, enabled engagement. However, the range of other programmes targeting work and health in both sites sometimes meant some professionals were less keen to get involved.

I think whether or not the local implementation boards, whether they were functioning well, whether there’s a public health lead champion as well I think makes a difference to get that engagement across systems and system partners. Then I suppose it’s the history of what else has happened before in those areas around employment and what the organisational memory is for frontline clinicians.

SCR health systems stakeholder

While there was central co-ordination, trial providers also needed to establish health sector relationships locally.

The organisational context supported the ease of this engagement. It is notable that the NHS Trust provider in WMCA received 28% of their referrals from GPs, 15 percentage points higher than any other WMCA provider. This provider had a different context as an NHS organisation. As such, the employment specialists who were also seen as NHS staff had greater traction and were better able to engage health sector colleagues with the narrative that the trials might reduce demand for wider health services. Being employed by an NHS organisation had other advantages. These employment specialists could send communications to health sector staff which were perceived as internal to the NHS rather than arriving from an external contractor. This built trust, quicker engagement and attracted more referrals. This provider was also able to draw on support from organisational experts about the benefits of good quality employment for individuals’ mental health and wellbeing. In contrast, employment specialists in the WMCA providers specialising in employment services spoke of difficulties in becoming familiar with NHS systems and processes, and differences in the language used. In SCR, the context of collaboration during design with health systems was a key factor that enabled easier engagement.

Neither engagement leads within the programme team, nor employment specialists had capacity to undertake detailed engagement with the full number of potential referral agencies, including successfully negotiating with gatekeeping organisations (for example, CCGs, local medical committees) (a planned mechanism).

When the WMCA programme team tried to incentivise the engagement of GPs (by setting a target number of referrals based on patient populations) (see section 4.2.1 of the implementation and 4 month outcomes report), the proportion of referrals from the healthcare sector increased. This strategy focused on specific settings rather than the whole trial geography. Overall, the number of referrals from GPs was similar between the two sites. The presence of strong and active GP leads who fully engaged with the trials was a useful mechanism to promote referrals. As discussed in the implementation and 4 month outcomes report (sections 2.2.1 and 3.2.1), the operation as a randomised controlled trial (RCT) created reluctance among some healthcare staff to refer patients as some would be allocated to the control group where they would not receive employment support unless they sought it from other services.

Different resources and contexts led to inconsistent engagement with the trial both within and between healthcare settings.

While healthcare settings were able to make referrals, time constraints, and the existing purpose of their patient interaction meant that they did not all have the same motivation or natural opportunity to refer. The capacity of health professionals to discuss employment and refer varied depending on the nature of the appointment and the length of time during which the patient was engaged with their service. Furthermore, the data captured on systems did not always enable health staff to review records or send communications based on a patient’s work situation. These barriers were especially acute for GPs.

I think they’d [GPs] all see the value, but if you’ve got a queue of patients outside your door you can’t maybe give them long enough individually to make this kind of referral.

SCR health systems administrator

As noted in the implementation and 4 month outcomes report sections 2.2.1 and 3.2.1, the large number of self-referrals recorded will include some recruits who heard about the trials from within healthcare settings.

Longer appointment times and ongoing engagement enabled referrals (in smaller GP practices, or as standard for some types of health appointment).

For example, staff and wider stakeholders viewed IAPT services as effective referrers because they regularly engaged with the same patient over several weeks or months. Additionally, the nature of the support meant that these health staff felt it was reasonable to discuss work with patients. It was also mentioned that IAPT staff were more likely to be aware of and supportive of IPS services, which also led to positive engagement. Other health partnerships were felt to be more reactive and less consistent referral sources. For example, they might mention the service if employment came up in a conversation with a patient a GP knew well.

We found IAPT were good at getting people in and then knew who needed to go in, they were particularly good, but GPs were pretty good at it, it varied between practice to practice. I think some of our smaller practices were probably more effective than the really big ones, probably because you see the same GP on a regular basis.

SCR health systems administrator

Referrals from MSK services were not particularly prevalent in either site.

Referrals were only felt to be appropriate from these settings if a patient was engaging because of an issue that affected their work or ability to work. The nature of the interaction and likelihood of fewer consecutive appointments did not support referrals either. This underlines the importance of the relationship between the healthcare professional and patient, and the context and purpose of their appointment. Employment was easier to raise in some situations than others.

Trial stakeholders felt there was a degree of over optimism about uniform primary and secondary healthcare engagement in referrals.

While all settings had access to referral systems, the varied time spent with patients, and the focus of patient interaction, meant that some health settings were more willing to refer patients than others. Locally, different structure and commitment from senior leaders also created a mechanism for engagement:

In our area if you were to highlight the areas where we have got it embedded: a really good GP leader, working in a strong primary care network, that has the ethos behind it, and the leadership to make it happen, all of those four boxes would absolutely be ticked. But it’s not the same everywhere and I think that’s the bit we would probably need to honest about.

WMCA employment and health systems stakeholder

The planned mechanisms to underpin health system change held true in certain contexts.

Different organisational cultures, practices, and barriers the sites experienced show that differentiated and targeted approaches were required to engage the many organisations that form the healthcare system. Health professionals interact with patients for different reasons and over varied timeframes. An understanding of these different contexts is crucial to ensuring the feasibility of the planned mechanisms.

3.3 Partnership working between health teams and trial staff

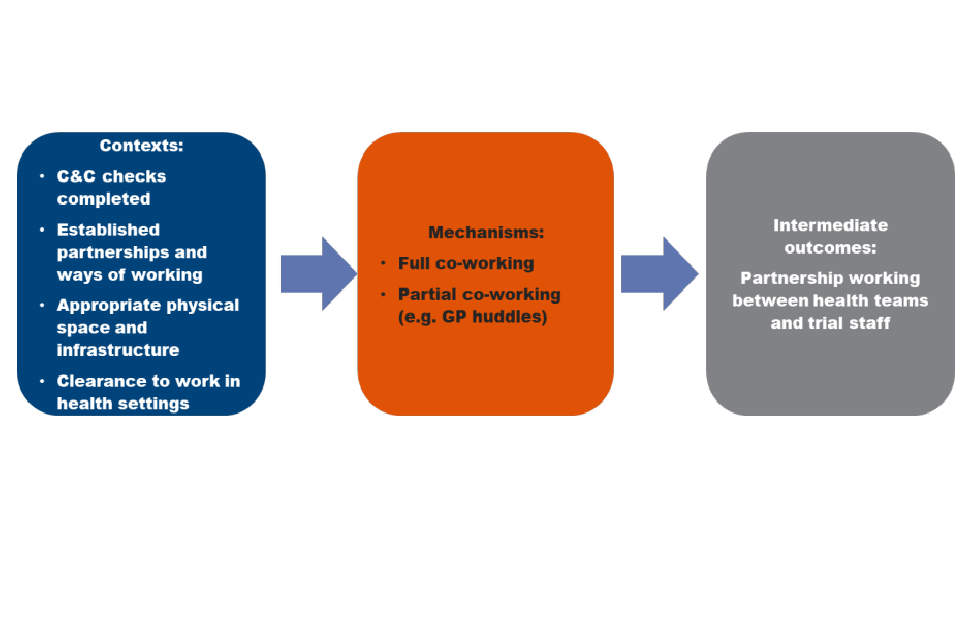

The establishment of co-working between employment specialists and health teams intended to assist the coordination of support for the treatment group and change in health systems (planned mechanism).

Co-working was intended to support the assumption outlined in the intervention-level ToCs that the integration of employment and health support enables complex patient needs to be addressed in a coordinated way, a key principle of the IPS approach. It was recognised that integration could be implemented in several ways, not least because operational constraints meant that full co-location would not be possible in all cases. Envisaged integration options therefore included full-time co-location, part-time co-location and modified co-location (that is, where IPS specialists were based alongside health teams but provided support in the community).

The pace with which capability and capacity (C&C) checks were granted to enable employment services to deliver the trial in health settings varied between and within the trial sites.

Employment specialists needed to be authorised locally by health systems to assess and confirm whether the organisation had the resources, policies and service users required to successfully deliver the trial to time and target. In WMCA, C&C checks were granted from August 2018, but were not all in place until early 2019, 8 months into trial delivery. In SCR, by contrast, all trusts had completed and been granted C&C checks by May 2018 as trial delivery commenced. In WMCA, these delays prevented the aim of co-location.

Co-working was the exception rather than the rule, but where it occurred it supported integration.

Trial providers were not supported to integrate systematically with health services and employment specialists felt that more planning and momentum was needed to set up effective partnerships. There were other barriers such as a lack of suitable physical space and infrastructure. In WMCA, it was notable that the health sector provider found it easier to make such arrangements, seemingly because they were part of the NHS, and had clearance to operate in health settings. Co-working was also enabled where employment specialists had been recruited from NHS roles as they brought health sector networks and relationships. In SCR, co-location was supported by health partners being part of the trial design team, and from ongoing work and resource to develop social prescribing services and non-clinical support services across the trial site. Health settings that made referrals to employment and community services prior to the trial were most receptive to full engagement with trial providers. The result was some examples of health team co-location in settings keen to embrace the employment specialist, including some GP practices and within IAPT.

Where co-location (planned mechanism) occurred, it had several benefits, as envisaged in the ToC.

Physical integration was intended to support co-working practices and encourage referrals. Providers and health partners reported an increased likelihood of referrals from sites where there was co-location, increased trust (both from potential recruits and referring practitioners) and higher attendance at appointments. It also led to increased understanding of the benefits of IPS support amongst health practitioners, and a better level of support through joined up care, cross-referral, and signposting. Where there were closer relationships with healthcare teams, employment specialists were able to speak to them about the trials and individuals they referred (see the implementation and 4 month outcomes report sections 2.2.1, 2.3.4, 3.2.1, 3.3.4). The context made it challenging to implement this mechanism but where it was possible, it supported health system outcomes.

However, full co-location was not always necessary to gain some of its benefits. For example, there were cases of employment specialists attending ‘GP huddles’ where they discussed the trials and provided a named point of contact for health professionals to answer questions and build trust in the service. While these approaches facilitated awareness, and referrals, they did not support other aspects, such as case conferencing.

3.4 Major outcomes

It was anticipated that the intermediate outcomes would lead to the following major outcomes:

-

that health professionals view conversations about employment with patients as a key part of their role

-

that health professionals have a better understanding of the relationship between work and health and recognise the therapeutic value of work

-

that health professionals see it as part of their role to make wider referrals outside of the NHS, including to employment services

However, because the enabling intermediate outcomes relating to referrals and partnership working were achieved only in some locations, and not habitually across the trials, there are some examples where these major outcomes occurred, but they are not consistent. A greater focus on these in implementation would allow this causal pathway to be better interrogated.

The planned mechanism of positive feedback from patients led to greater understanding among some health professionals of the relationship between work and health

This included positive stories from patients about the support they had received and the difference they felt the trial had made. The planned mechanism of having employment specialists embedded in teams enabled them to have conversations about work and health, and for employment specialists to be a source of support and expertise on employment and related issues.

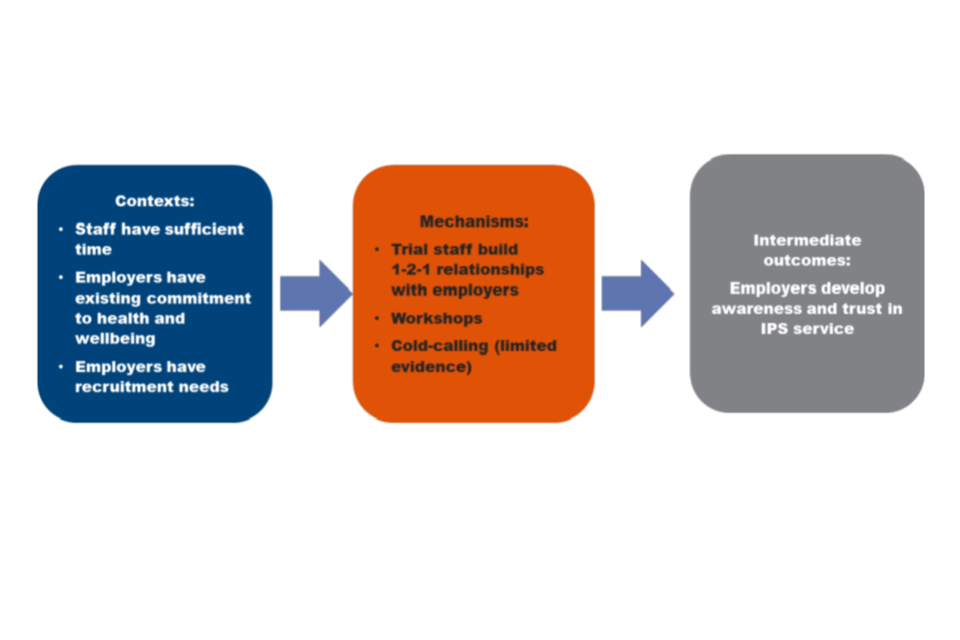

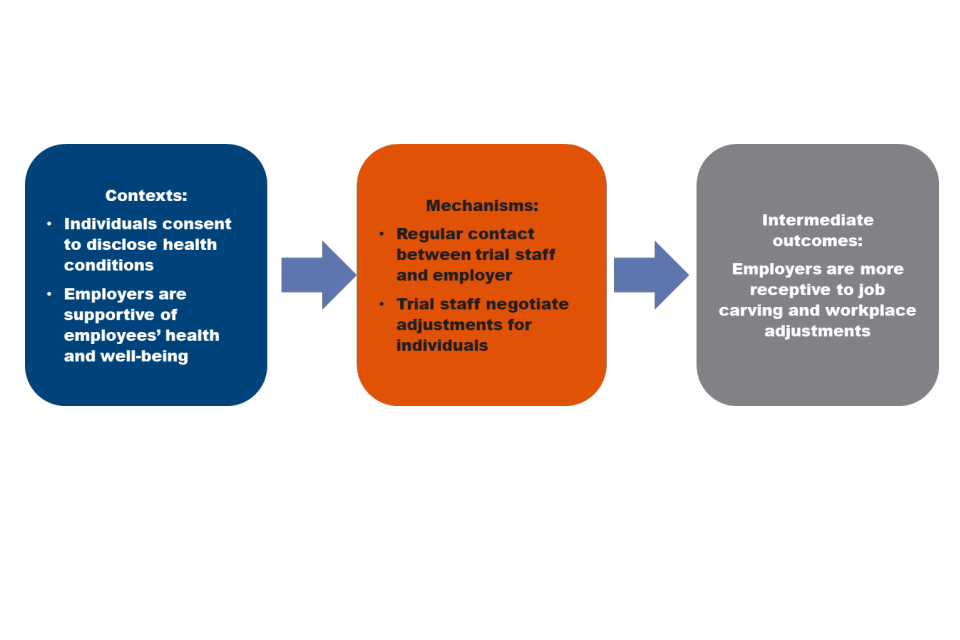

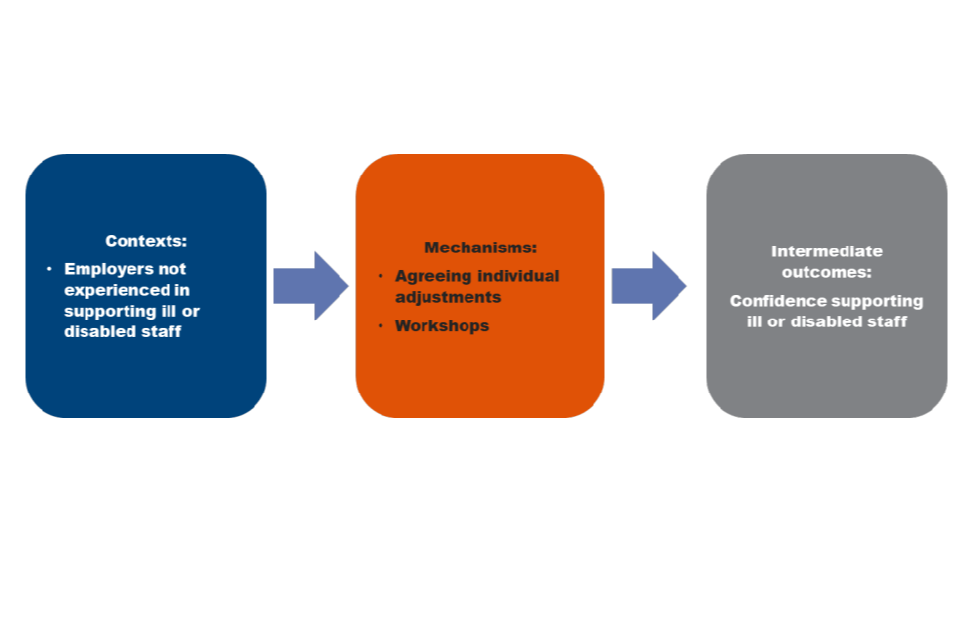

However, most examples of these outcomes were found among health services that reported they recognised and understood the relationship between health and work prior to the trials. Greater consideration at the outset could have been given to how to begin to change behaviour among staff and create a strong presence and co-working in settings where this was not already the case.