Health matters: smoking and quitting in England

Published 15 September 2015

Summary

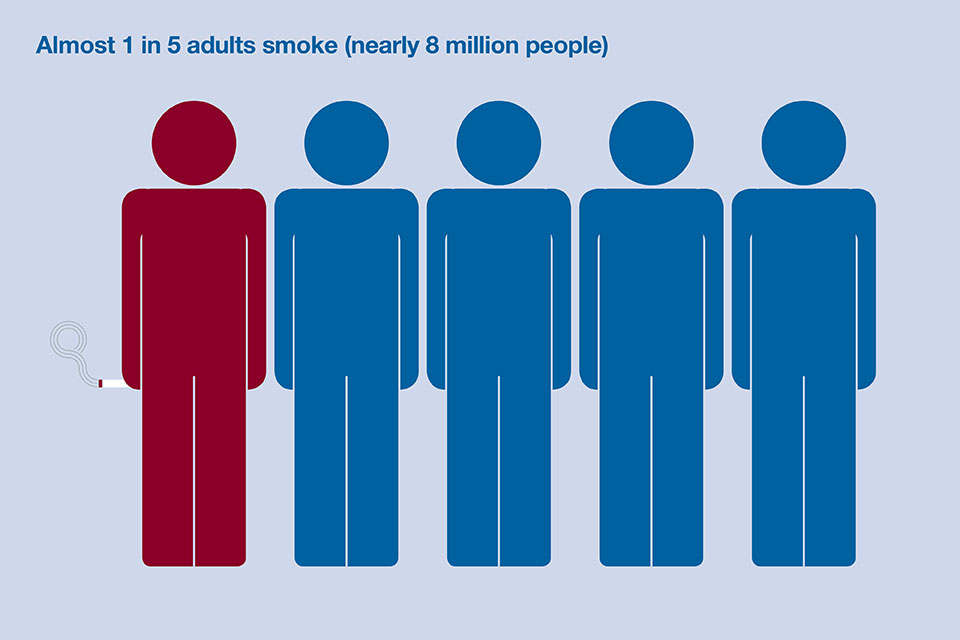

Public Health England (PHE) wants to see a tobacco-free generation by 2025. Despite a continuing decline in smoking rates, nearly 1 in 5 adults still smoke and there are around 90,000 regular smokers aged between 11 and 15. The following shows what we know works to help people stop smoking.

Who smokes

Nearly 1 in 5 adults smoke and there are around 90,000 regular smokers aged between 11 and 15. Smoking causes 17% of all deaths in people aged 35 and over. The following information shows what we know works to help people stop smoking so we can get to a tobacco-free generation by 2025.

Estimates of youth smoking rates for every local authority, ward and local NHS level are available on PHE’s Health Profiles website

Smoking reinforces health inequalities

Smoking and the harm it causes aren’t evenly distributed. People in more deprived areas are more likely to smoke and are less likely to quit. Smoking is increasingly concentrated in more disadvantaged groups and is the main contributor to health inequalities in England. Men and women from the most deprived groups have more than double the death rate from lung cancer compared with those from the least deprived. Smoking is twice as common in people with longstanding mental health problems.

There are relatively high smoking levels among certain demographic groups, including Bangladeshi, Irish and Pakistani men and among Irish and Black Caribbean women. Smoking in pregnancy increases the risks of miscarriage, stillbirth or having a sick baby, and is a major cause of child health inequalities. At the time of their babies’ birth, over 1 in 4 pregnant women are recorded as smokers in Blackpool, but fewer than 2 in 100 in the London Borough of Westminster.

The Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England provide a snapshot of the extent of tobacco use, tobacco-related harm and measures being taken to reduce this harm at local level.

There are encouraging trends, but some groups don’t benefit as much as others. The number of smokers has fallen by roughly 30% over the past 20 years, but it’s barely changed among people with mental health problems.

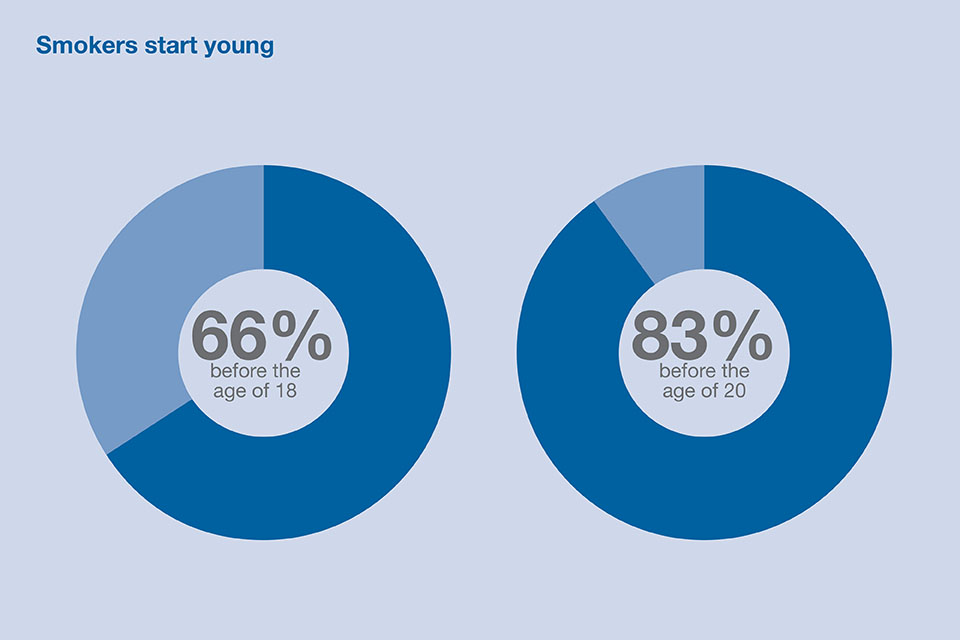

Starting young

Most smokers start as teenagers: two-thirds before the age of 18. The reasons they start are complex, ranging from peer pressure to behavioural problems. Children are more likely to take up smoking if they live with people who smoke. The best way to reduce smoking among young people is to reduce it in the world around them.

Reducing tobacco use

Helping smokers to quit is one strand of the government’s tobacco control plan for England. The other elements are:

- making tobacco less affordable

- preventing the promotion of tobacco

- effective regulation of tobacco products

- improving awareness of the harm

- reducing exposure to secondhand smoke

These actions need to take account of the wider issues people face in their lives. Many factors, from lack of opportunity to social isolation, can increase the risks of unhealthy behaviours.

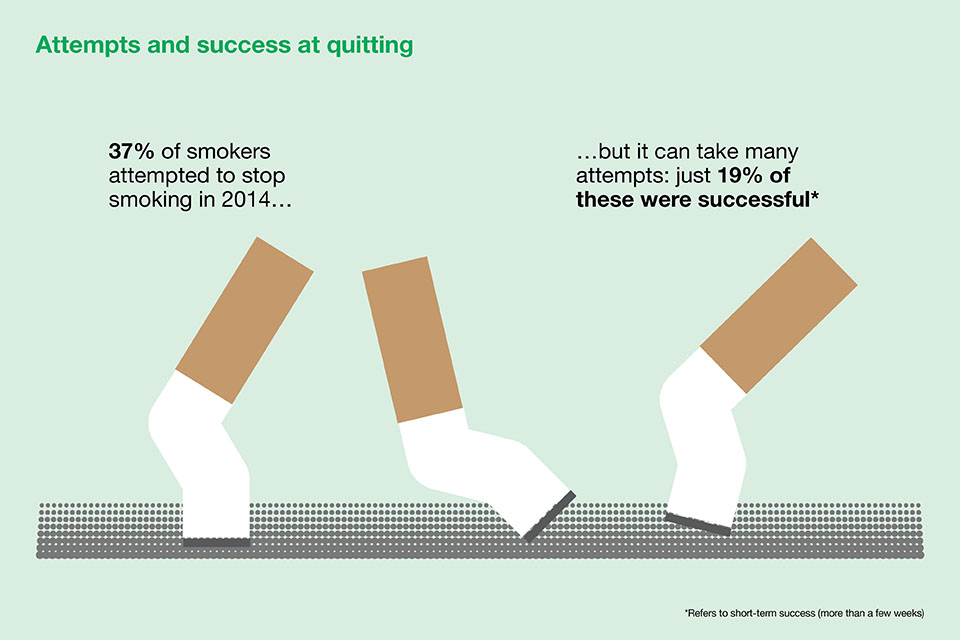

Who is trying to quit and how

Most smokers want to stop but quitting is hard. Many people make several attempts before they succeed. It’s even harder when people are dealing with stress in their lives.

To improve their chances of quitting, all smokers need:

- effective services and therapies

- supportive social networks

- smokefree environments

Local stop smoking services offer the best chance of success. They are up to 4 times more effective than no help or over the counter nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). However, the number of people using these services is falling. Around 450,000 people set a quit date through stop smoking services from April 2014 to March 2015. Instead, most smokers use the quitting methods with the least evidence of effectiveness.

Stop smoking services need good referral routes. Health professionals, such as GPs, midwives, pharmacists, dental teams and mental health staff are often well placed to refer smokers to these services. Services also need to be responsive to local needs and targeted to provide the right support to the people who need it most. For example, people with mental health problems may need higher doses of NRT and more intensive behavioural support than the general population.

Many people are choosing to use electronic cigarettes to help them quit smoking, even though they are not licensed as medicines. Regular electronic cigarette use is confined almost entirely to smokers and ex-smokers. Electronic cigarettes are now the most popular quitting aid, according to a survey in the Smoking Toolkit Study, and emerging evidence indicates they can be effective for this purpose.

Smokers who want to use electronic cigarettes to help them quit should seek the expert support of their local stop smoking service. Stop smoking services should provide them with the support they need to stop successfully. PHE encourages all electronic cigarette users to quit tobacco use.

Important facts include:

-

2.6m adults use electronic cigarettes in Great Britain

-

3 in 5 electronic cigarette users are current smokers

-

2 in 5 electronic cigarette users are ex-smokers who have switched to vaping

PHE also provides support through products, such as apps, text and email programmes and packs from Stoptober and Smokefree to help people quit.

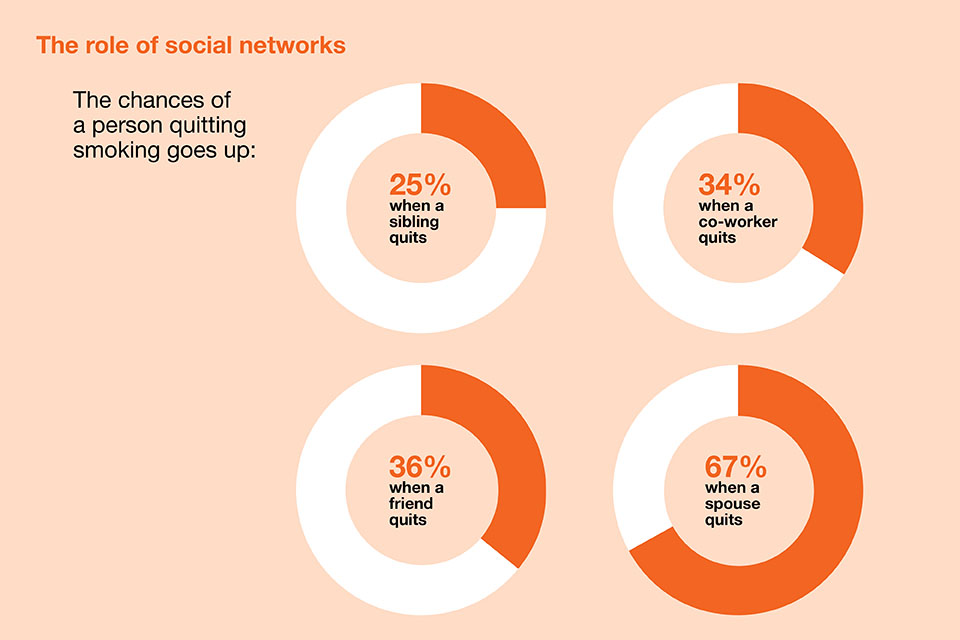

The influence of networks and places

A person’s decision to quit smoking and the ability to stay smokefree is influenced by their social network. Research suggests that smoking cessation spreads through social networks just as smoking does.

The successful (and cost-effective) Stoptober campaign uses the power of social networks in the local community. It does this through employer networks and online, encouraging people to attempt to quit and supporting them through it.

PHE provides a range of resources to enable local areas, other government departments and employers to make the most of the momentum created by Stoptober to encourage quit attempts in their own environment.

The NHS and local government, in particular, have a major contribution to make as employers of 1.3 million people and 1.6 million people respectively.

Smokefree environments

Smoking cessation should be a priority in settings where prevalence is high, such as prisons and mental health units. This can be promoted via smokefree grounds and buildings, and with on site stop smoking services.

PHE has produced guidance to help mental health units implement NICE recommendations and to help prisons manage smoking and nicotine withdrawal.

Throughout the NHS, healthcare professionals should feel confident and competent to ask about smoking and help signpost patients towards effective support to quit smoking. This includes acute trusts, primary care and maternity services.

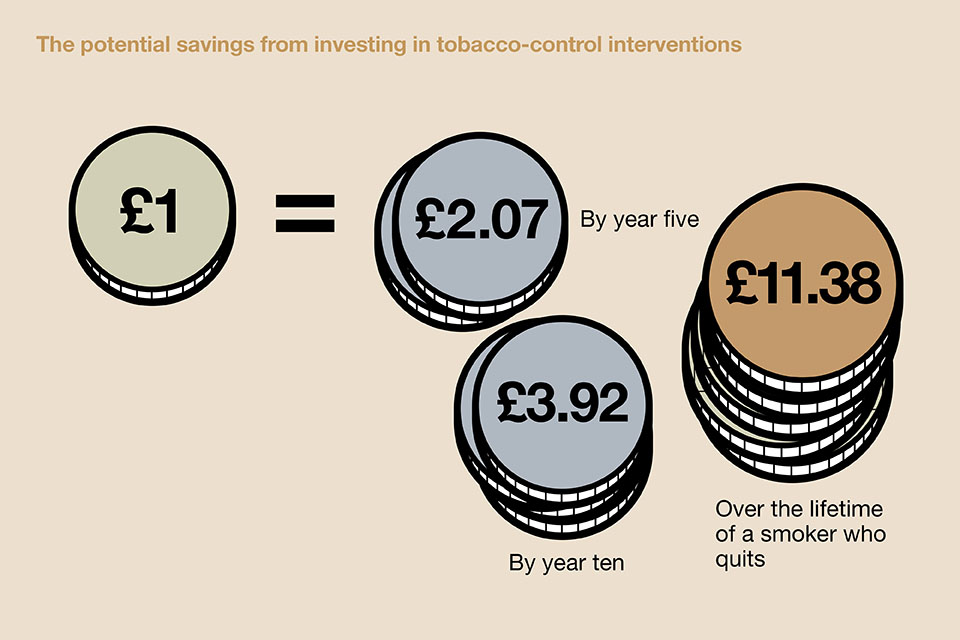

The benefits of investing

Helping people to stop smoking is a good use of scarce resources and can save money for individuals, for the NHS and for society as a whole.

ASH Ready Reckoner estimates the costs of smoking at regional, local authority and ward levels . This includes lost productivity for businesses, health and social care costs from ill health due to smoking and secondhand smoke, and costs due to fire and litter.

A number of other tools can help commissioners, providers and policymakers quantify the costs and savings that different tobacco control measures offer.

The NICE tobacco return on investment (RoI) tool includes 28 local tobacco control interventions.

Different packages of interventions can be compared and analysed for economic impact at local level including:

- net savings

- savings in resources eg number of GP visits or hospital admissions

- wider savings such as productivity gains and costs per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained

NICE and PHE provide resources and user support to help implement the NICE RoI tool at local level (by local authority or Clinical Commissioning Group).

A worked example from Sunderland

NICE guidance also includes tools that show the financial impact of brief interventions and referrals by GPs (PH1), and the cost-effectiveness of workplace interventions to promote smoking cessation (PH5).

The National Social Marketing Centre has a tool to calculate the savings and cost-effectiveness of social marketing projects to reduce smoking.

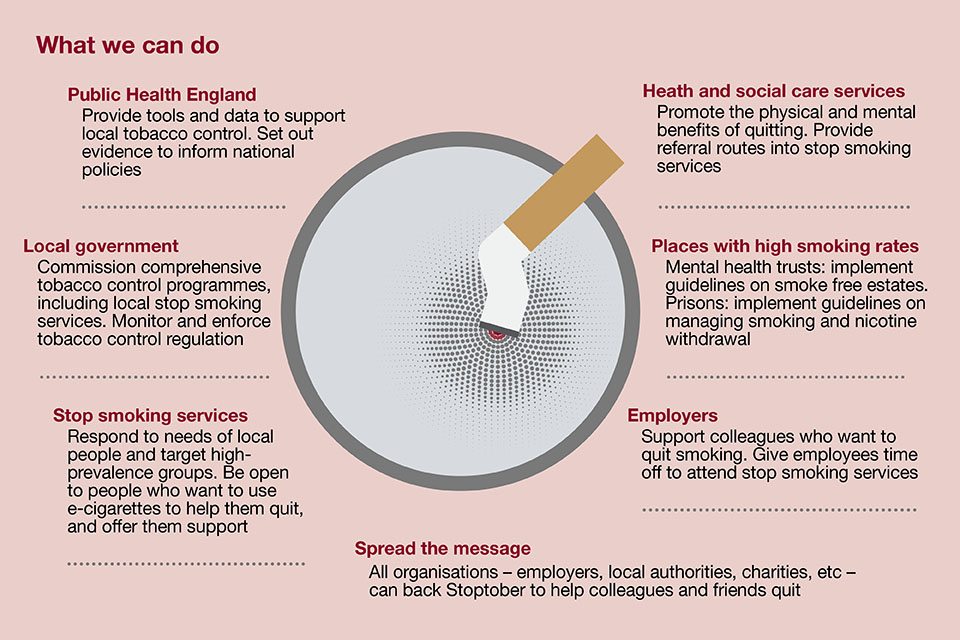

What we can do

We need to step up our efforts to help people quit, especially those groups with the highest smoking rates and lowest quit rates. The prize is huge, both for individuals and the population as a whole.

Quitters will start to see benefits quickly and these increase dramatically the longer they stay smokefree. After just 48 hours of stopping, there’s no nicotine in the body and quitters may start noticing that things smell and taste better. Within 1 to 9 months of quitting, coughing and shortness of breath decrease. After 1 year, the added risk of a heart attack falls to about half of that of a smoker’s.

Stopping can also help to improve symptoms of mental health problems in the longer term. It is also associated with improvements in mental health, including depression, anxiety and stress. This seems to apply both to the general population as well as to people with mental health problems.

Across the population, we’ll do more to tackle health inequalities if we’re able to reduce smoking rates in more disadvantaged groups. We’ll also address the unacceptably high numbers of people dying from smoking related diseases: 78,200 in 2013.

This resource sets out the actions that PHE, together with its stakeholders, can take to boost the numbers of people who try to quit and succeed.

Download a complete set of references for this document.

For any questions on this resource, please e-mail: [email protected].