Country policy and information note: gangs, Honduras, November 2023 (accessible)

Updated 23 August 2024

Version 1.0, November 2023

Executive summary

The main criminal gangs operating in Honduras are Mara Salvatrucha 13 (MS-13) and Barrio 18 (Pandilla 18 or 18th Street gang). They generally operate and exercise control within the 3 main cities of Tegucigalpa and its surrounding area, San Pedro Sula, and La Ceiba.

Gang members are usually youths/young men under 26 years old from poor backgrounds with little formal education or previous employment. Women are also recruited into gangs. Children as young as six can be forcibly recruited into gangs.

Gangs’ main activities and sources of revenue are extortion and drugs smuggling, and exercising control of territory through violence, often influencing entire neighbourhoods. Gangs may also impose invisible borders, curfews and dress codes within areas under their control. Gangs routinely use violence and intimidation in their criminal activities and maintaining control of territory.

A person fearing persecution from MS-13 or Barrio 18 is not likely to fall within the Refugee Convention on the grounds of political opinion. However, women, former gang members, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or intersex (LGBTI) persons are likely to demonstrate a nexus to the RC as members of a particular social group.

A person is likely to face persecution or serious harm if they live in an area controlled by MS-13 or Barrio 18 and

-

are considered to be a threat to the gang and/or

-

have not complied with a gang’s rules or demands and/or

-

belong to a particularly vulnerable group, such as being female or a LGBTI person

The state is likely to be willing but not able to provide protection.

Internal relocation is likely to be viable depending on the facts of the case.

A refused claim is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Assessment

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

-

a person faces a real risk of persecution/serious harm from a gang

-

a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

-

a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

-

a grant of asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave is likely, and

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

This note primarily focusses on the activities of street gangs, or ‘maras’, primarily the 2 dominant groups: Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13 or Mara 13) and Barrio 18 (also Pandilla 18 (or 18th Street Gang)). However, there are a number of other international and domestic organised criminal groups operating the Honduras, primarily involved in drugs trafficking from South America into the USA and Canada.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use only.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use only.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 A person who fears one/both of the 2 dominant gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18, or a smaller gang is not likely to be able to demonstrate a link to the Refugee Convention on grounds of political opinion.

2.1.2 However, a person who fears a gang may belong to a particular social group (PSG) under the Refugee Convention where they have

-

an immutable characteristic/common background/belief or characteristic so fundamental that a person cannot be expected to renounce this and

-

a distinct identity within Honduran society.

2.1.3 The following groups are likely to form a PSG:

-

women/girls

-

lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intesex (LGBTI) persons

-

former gang members (see Targets of gang violence)

2.1.4 In the country guidance case of EMAP (Gang violence, Convention Reason), heard on 27 April and 9 June 2022 and promulgated on 16 November 2022, the Upper Tribunal (UT) considered whether persons who fear a gang in El Salvador fall within the scope of the Refugee Convention on the grounds of political opinion and membership of a PSG.

2.1.5 The UT in EMAP held that the main gangs operating in El Salvador, MS-13 and Barrio 18, are ‘political actors’ and that:

‘… (ii) Individuals who hold an opinion, thought or belief relating to the gangs, their policies or methods hold a political opinion about them.

‘(iii) Whether such an individual faces persecution for reasons of that political opinion will always be a question of fact. In the context of El Salvador it is an enquiry that should be informed by the following:

‘(a) The major gangs of El Salvador must now be regarded as political actors;

(b) Their criminal and political activities heavily overlap;

(c) The less immediately financial in nature the action, the more likely it is to be for reasons of the victim’s perceived opposition to the gangs.’ (Headnote, paragraphs (ii) and (iii))

2.1.6 The UT in EMAP provided further analysis of the applicability of political opinion in paragraphs 112 to 122 of the determination. It considered that there are a range of reasons why a gang (or gangs) target a person, not all of which will fall within the Refugee Convention.

2.1.7 The UT’s findings in EMAP are specific to El Salvador but the situations in El Salvador and Honduras are similar and merit comparison. Both have high levels of organised crime dominated by the same gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18, which have de facto control over parts of the country and have sought to influence the state (see Risk).

2.1.8 However there are significant differences between the 2 countries:

-

Honduras has a more diverse criminal landscape with a number of organised criminal groups - international drugs cartels as well as smaller local outfits - working and competing with MS-13 and Barrio 18. As a result, MS-13 and Barrio 18 are not as dominant as their counterparts in El Salvador (see Risk).

-

MS-13 and Barrio 18 are reported to be absolutely and relatively smaller in Honduras (upto 40,000, 0.4% of the population) than in El Salvador (60,000 members, 1% of the total population). As a consequence, gangs in Honduras exert less control. While there are no detailed figures on the extent of MS-13’s and Barrio 18’s control / influence in Honduras by taking gang-linked crime as a proxy for control, less than 75% of municipalities had a homicide (more than 25% did not), while 85% extortion is concentrated in just 5% of municipalities. In comparison in El Salvador sources describe gangs having control or exerting influence in over 94% of the country (see EMAP, Risk, Internal relocation and Gangs size and location)

-

MS-13 and Barrio, and gangs generally including international drugs trafficking groups, have sought to influence the state. However, MS-13 and Barrio 18’s influence on political affairs is not as extensive as in El Salvador (see Risk and Gangs in politics).

2.1.9 On the available evidence, the situations are sufficiently different to conclude that gangs are not ‘political actors’ and that the UT’s findings in EMAP do not apply to a fear of gangs in Honduras. Therefore a person who fears a gang in Honduras does not fall within scope of the Refugee Convention on grounds of political opinion. However, the UT’s findings in EMAP with regard to women, LGBTI persons and former gang members forming PSGs are likely to apply to Honduras (see Risk).

2.1.10 Establishing a Convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.11 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1 In general, a person living in an area controlled by MS-13 or Barrio 18 who is considered to be one or more of the following:

-

a threat to the gang and/or

-

has not complied with a gang’s rules or demands and/or

-

belongs to a particularly vulnerable group (for example a woman or LGBTI person)

is likely to face persecution or serious harm in that area.

3.1.2 Each case will need to be considered on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate a risk of persecution or serious harm.

3.1.3 Honduras has a more diverse criminal landscape than the neighbouring ‘Northern Triangle’ countries of El Salvador and Guatemala. There are esimtated to be 40+ organised criminal groups (OCGs) operating. However 2 gangs (or mara) dominate: MS-13 and Barrio 18 (see Organised criminal groups (OCGs), including gangs).

3.1.4 There is limited detailed information about the areas that MS13 and Barrio 18 contol or exert influence over. Sources indicate these gangs are concentrated in the 3 main cities: the capital, Tegucigalpa and its surrounding area, the economic hub of San Pedro Sula, and La Ceiba. One source, the expert Maria Gomez, observed gangs were in predominantly in poor, marginalised urban neighbourhoods (colonias). International Crisis Group stated gangs are expanding into coastal areas and along the borders with El Salvador and Guatemala. Human Rights Watch claimed that while gangs only controlled some areas they are able to extort people throughout the country – however they did not provide detailed evidence of this and other sources do not provide corroboration (see Control of territory, Freedom of movement and Gang size and distribution).

3.1.5 Gangs impose curfews, dress codes, and restrict entry to, and movement within, and access to public services in areas they control (see Control of territory, Freedom of movement and Gang size and distribution).

3.1.6 There are not reliable statistics of the number of gang members, with estimates ranging between 5,000 and 40,000 (0.05 to 0.4% of the total population). The Honduran National Police (HNP) estimate there are 25,000 active members of MS-13 and Barrio 18 but other sources provide lower figures (see Geographical context and Gang size and distribution).

3.1.7 Gang members are usually males aged younger than 26 years old from poor backgrounds with little formal education or previous employment. Gangs recruit and use children to act as look-outs and to collect extortion money. Boys may be targeted from age 6 and girls from age 8. Girls may also be used for sexual exploitation, some being forced to become ‘girlfriends’ of gang members. Gangs sometimes also forcibly recruit members, including from within schools, where pupils are targeted by peers with gang associations. Sources noted that it is possible to leave a gang, usually to join a church or faith group. However this often requires the permission of the gang leader, while those entering the church are tracked to ensure their religious calling is genuine (see Structure and Profile of memebers).

3.1.8 Gangs’ main source of revenue is drug smuggling (particularly MS-13) and extortion of individuals and businesses (particularly Barrio 18). Gangs are involved in other criminal activities including robbery, drug dealing, gun sales, carjacking, kidnapping, prostitution and human trafficking (see Extortion and Gangs’ activities and impact)

3.1.9 Gangs harass, intimidate, use violence, including torture and murder, against persons who they consider to be a threat or who do not comply with their demands and to exert territorial control. Persons targeted include rival gang members and their families, business owners who resist extortion, passengers on public transport, and persons who have, or are perceived to have, collaborated with security forces, such as informants and witnesses. Other vulnerable groups include persons – and their friends and families – who refuse to join a gang, who have left or want to leave a gang or who are perceived to have betrayed a gang (see Gangs’ activities and impact and Targets of gang violence)

3.1.10 Women are also involved with gangs but are unlikely to been seen as equal to male gang members. Gangs may sexually abuse women and girls, and those who refuse sexual involvement with gang members may face violent reprisals. Women and girls who are not linked to gangs but who live in areas controlled by them may be vulnerable to violence and intimidation, including sexual violence and forced prostitution (see Characteristics of gang members, Gangs’ activities and impact and Targets of gang violence)

3.1.11 Gangs are reported to coerce LGBTI persons to assist with criminal activities. LGBTI persons may also be subjected to violence, such as corrective rape, or forced to leave gang-controlled areas (see Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex persons)

3.1.12 Gang activity and the use of initimidation and violence has displaced tens of thousands of Hondurans, both within and outside the country. The International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) in a report from 2019 suggested that returnees may be threatened by gangs because they are perceived to have resources. A couple of sources cited by the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin Asylum Research and Documentation observed some returnees have been killed by gangs after their return, with one expert stating she was aware of over 100 murders at some point following return since 2014. However, detail is absent about these cases, with some deaths occurring months or even a year after return see Displacement and Returning migrants).

3.1.13 Over 500,000 people returned to Honduras in the period January 2015 and July 2023. Other sources consulted do not describe a clear causal link between return and violence from gangs. Taking the scale of returns compared to the small number of returns who mayu have faced problems because of their status as a returnee, and the relatively high levels of violent crime, the evidence does not indicate that returnees are targeted by and are generally are at risk from gangs per se see Displacement and Returning migrants).

3.1.14 Whether a person is at risk from a gang will depend on:

-

their profile, actions and reason(s) for the gang’s interest

-

the area the person usually resides and will return to

-

the gang’s intent, size, reach and capability

3.1.15 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 In general, the state is willing but owing to a lack of resources and competence, and high levels of corruption, is unlikely to be able to provide effective protection. Each case must be considered on its facts, taking into account the nature, capability and intent of the gang and profile of person.

4.1.2 Honduras has introduced various ‘iron fist’ policies, most recently the state of exception in December 2022, to combat gang activity (see Government strategy to combat gangs).

4.1.3 The Honduras National Police (HNP), which has around 17,000 officers, is responsible for maintaining public order. It includes specialised teams such as an anti-gang unit and has a separate oversight body. The army can support police operations targeting arms and drug trafficking, including gang activities. There is a functioning judicial system with first instance and appeals courts established to consider civil and criminal cases. The current government has taken steps to strengthen the rule of law and judicial independence (see Protection).

4.1.4 The government has had some success in dismantling drug-trafficking groups. Over 4,000 gang members were arrested between 2015 and 2019, and the government has claimed to have arrested thousands more since the introduction of the state of exception in December 2022. The US State Department acknowledged that the government has investigated and prosecuted some gang-related crimes (see Police effectiveness).

4.1.5 However, sources consider the HNP to be under-staffed and under-equipped, with high levels of corruption. There are also reports that some police have been involved in criminal activity and collaborated with gangs. Some sources suggest that due to a lack of resources many crimes are not fully investigated, and when investigations do take place they are lengthy and inefficient leading to high levels of impunity. Some people are reluctant to file complaints for fear of reprisal or retaliation from gangs and lack of confidence in state institutions. However a reluctance to seek protection does not in itself mean protection is not available (see Police effectiveness).

4.1.6 A witness protection scheme exists but is underfunded, understaffed and ineffective. If a conviction is secured then witness protection comes to an end, leaving the witness vulnerable to orders issued from prison (see Witness protection)

4.1.7 The judiciary’s effectivessness is hampered by being poorly resourced and subject to intimidation, political influence, and corruption. The USSD observed that criminal groups are able to exercise influence on the outcomes of court proceedings. As a result, there are reportedly high rates of impunity and barriers to accessing justice (see Judiciary).

4.1.8 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 In general, internal relocation is likely to be reasonable depending on the facts of the case. Decision makers must consider the profile of the person, their previous experiences, the reasons why the gang has an interest in them, and the size, capability and intent of the gang they claim to fear.

5.1.2 Honduras is about half the size of the UK. More than 60% of its over 10 million population live in urban areas, mostly in the main cities of Tegucigalpa and its surrounding area, San Pedro Sula, and La Ceiba. Gangs control some parts of the 3 main cities – usually the poor and marginalised neighbourhoods – plus several municipalities in rural areas. However, there are parts of the main cities and some rural areas where gangs do not have control, or exert influence. This is evident by using the distribution of homicides and extortation as proxies for gang control and influence: Infosegura reported that over 25% of municipalites had no reported homicides and that 85% of extortion took place only in 5% of municipalities (see Geographical context and Freedom of movement).

5.1.3 The IDMC report of 2019 stated that people who gangs believe are guilty of betrayal or emnity may be tracked by them. The source also noted the chances of finding safety in another area vary according to economic resources: safer neighbourhoods are generally more expensive and often gated (see Displacement).

5.1.4 Gangs monitor movement in and out of areas they control and reportedly check people moving from one gang-controlled area to another, with reports that residents must request and pay for a permit to travel between neighbourhoods. LGBTI persons, women, girls and youths, without support networks, may be particularly vulnerable to abuse and may find it difficult to support themselves in areas of relocation (see Gangs size and reach, Women and children, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex persons, Displacement and Freedom of movement)

5.1.5 For more on internal relocation and factors to be taken into account, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content of this section follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

Updated to 6 October 2023

7. Geographical context

7.1.1 Honduras is 112,492 sqkm[footnote 1], just under half the size of the United Kingdom (about the size of England)[footnote 2]. The population is estimated to be around 10 million[footnote 3] [footnote 4], with 6 million in urban areas of whom 1.5 million live in the capital, Tegucigalpa[footnote 5], and 1 million in the second city, San Pedro Sula[footnote 6].

7.1.2 The US CIA World Factbook noted ‘most residents live in the mountainous western half of the country… [the] urban population… is distributed between two large centers - the capital of Tegucigalpa and the city of San Pedro Sula; the Rio Ulua valley in the north is the only densely populated lowland area’[footnote 7].

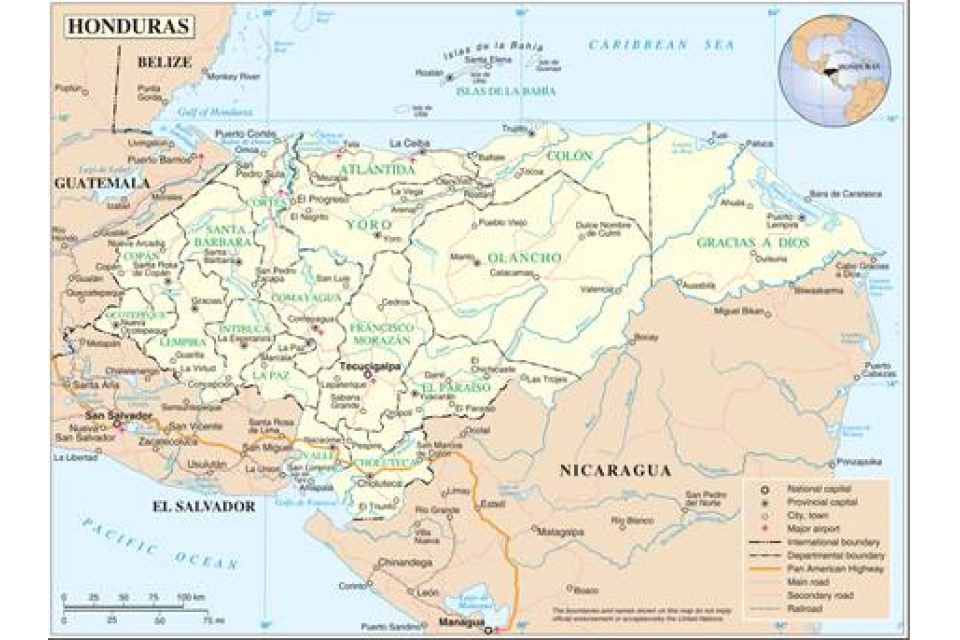

7.1.3 Honduras is comprised of 18 departments (departmentos)[footnote 8], which are subdivided into 298 municipios (munciplaities) then aldeas (villages/hamlets) in rural areas[footnote 9] and colonias (neighbourhoods) in cities[footnote 10] [footnote 11]. The UN map below[footnote 12] describes the capital, main provincial cities/towns and departments:

7.1.4 The WorldPop website, operated by the School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton, Department of Geography and Geosciences, University of Louisville; Departement de Geographie, Universite de Namur) and Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University (2018), produced the map below[footnote 13] described population density and distribution:

7.1.5 Population data by department and municipality based on the Honduras National Institute for Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística Honduras; HNIS) is available on the website citypopulation.de.

7.1.6 Demographic as well as other socio-econonic data is available on the HNIS website but Spanish only.

Updated to 6 October 2023

8. Economic and political context

8.1 Castro government – January 2022 onwards

8.1.1 The UN High Commissioner of Human Rights report on the human rights situation in Honduras in 2022 (UN OHCHR 2023), 28 February 2023, noted

‘The arrival of a new government on 2 January 2022, led by the country’s first female president, with political will in the area of human rights and the fight against corruption, sets a new stage for human rights work in Honduras. The administration assumed its functions in a context of pre-existing structural challenges underlying human rights violations: poverty and inequality, land conflicts, violence, insecurity, impunity, institutional weakness and patriarchal culture, among others. Such challenges require short, medium and long-term measures to be resolved.’[footnote 14]

8.1.2 An International Crisis Group (ICG) report, ‘New Dawn or Old Habits? Resolving Honduras’ Security Dilemmas’, 10 July 2023, based on interviews with a range of interlocutors between September 2022 and June 2023 informed about the political and security situation, (ICG report 2023), noted

‘… left-leaning Xiomara Castro won the Honduran presidency by a large margin in November 2021. Her victory raised hopes for change in a country that, since a coup in 2009, has suffered soaring rates of violent crime and poverty, along with flare-ups of political unrest, all of which have helped drive an exodus of migrants and asylum seekers…

‘… [Previous] governments used heavy-handed tactics to fight crime, expanding the military’s role in public safety and working to break up drug trafficking organisations. The murder rate fell from a peak of 93 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011 to 38 per 100,000 in 2021. But even this lower rate makes Honduras one of the world’s most violent countries, and hundreds of city neighbourhoods remain under the control of criminal gangs.

‘… [Previous] governments’ collective record when it came to the economy and internal accountability were also a source of frustration among many Hondurans… Hondurans fleeing the country’s high crime rates and weak economy were apprehended more than a million times at the U.S. southern border between 2010 and 2021, while over 107,000 filed for asylum in Mexico… At the same time, a string of corruption scandals tainted politicians and high-level officials, including during the pandemic… Of these, the case that most tarnished the National Party’s image, and that of Hernández, was the former president’s brother Tony’s conviction in U.S. courts on drug trafficking charges…

‘Castro vowed in her electoral manifesto to reduce the army’s role in public safety, give greater powers to the national police, and encourage dialogue between police officers and the people they are charged to protect… But a quarrelsome start with Congress, high-profile violent crimes, an apparent surge in extortion and a desire to maintain public support have diverted her attention.’[footnote 15]

8.2 Economic situation

8.2.1 The World Bank in overview of Honduras, updated 4 October 2023 noted:

‘Annual real [Gross Domestic Product] GDP expanded by 4 percent in 2022, driven by remittance-fueled household consumption and increased private investment, despite global headwinds and the impact of Hurricane Julia (1.2 percent of 2021 GDP). Honduras’ economic growth is expected to slow to 3.2 percent in 2023. This is explained by slower growth of exports and especially of remittances, as they normalize following the exceptionally high 2022 inflows, in addition to low private investment and weak budget execution.

‘The inflation rate in 2022 rose to 9.1%, the highest since 2008, impacted by high global commodity prices, while monetary authorities did not hike the key policy interest rate. However, since February 2023, the inflation rate has been declining and is currently at 5.7% in August, helped by the decrease in international food inflation.

‘Honduras remains one of the poorest and most unequal countries in the region. In 2020, as a result of the pandemic and Hurricanes Eta and Iota, the share of the population living under poverty (US$6.85 per person per day at 2017 PPP) reached 57.7 percent, an increase from 49.5 percent in 2019. Since then, the recovery of the economy and the labor market, as well as the inflow of remittances, have contributed to reducing poverty. In 2022, the poverty level is estimated to have decreased to 52.4 percent, although this is still above pre-COVID levels. Extreme poverty (measured under the US$2.15, 2017 PPP line) is estimated at 13.3 percent for the same year, and the Gini Index, which measures inequality, is at 47.5.’[footnote 16]

8.3 Gangs and politics

8.3.1 The InSight Crime profile of February 2021, considering the situation before the current government came to power, noted:

‘Honduras is one of the most important drug trafficking operation centers between South America and Mexico. With all of its branches of government and its armed forces plagued by corruption, Honduras has evolved into a transit nation in which criminal groups, protected by the political system, have developed the capacity to produce cocaine hydrochloride in local laboratories.

‘Since the end of the last decade, political protection has allowed the traditional drug trafficking groups to flourish. Testimony provided by drug traffickers and Honduran politicians on trial in the United States have revealed the deep-seated connection between organized crime and the governing National Party [the National Party lost power following elections in November 2021].

‘Control of illegal activities in Honduras lies in the hands of local criminal groups connected with the country’s political and economic elite…’[footnote 17]

8.3.2 The InSight Crime Honduras profile updated February 2021 stated:

‘The former leader of the Cachiros Cartel, Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga, alleged in his testimony that he operated with the assistance or complicity of various political and economic elites. He even alleged bribing Tony Hernández [the brother of the former president, who was found guilty on cocaine and arms trafficking charges in a US court in October 2019].. . [Further] Tony Hernández acted as a link between the government and various drug trafficking groups, like Los Valle, Los Cachiros and the Atlantic Cartel.’[footnote 18]

8.3.3 The Honduras profile continued:

‘The Atlantic Cartel was another important group at the beginning of the century. The group is presumed to have operated under the protection of military agents, police and judges. Its leader, Wilter Neptalí Blanco, was arrested in Costa Rica in November 2016. As of July 2017, he has agreed to collaborate with the US criminal justice system.

‘On the other hand, several politicians on the local level – primarily associated with the National Party – have been linked to these structures, and it is presumed that they may have inherited the drug trade once the traditional kingpins were extradited. In El Paraíso, Copán, for example, former mayor Alexander Ardón controlled the drug trade from his municipality to Guatemala. In the remote region of La Mosquitia, a political clan formed by the Paisano Wood brothers operated a drug trafficking network in order to receive cocaine shipments and send them to the border with Guatemala. These types of examples of collusion between politicians and criminal actors, are repeated in various regions around the country, such as in Yoro, Lempira and Olancho.’ [footnote 19]

8.3.4 HRW’s world report, covering events in 2021, noted: ‘There have been repeated allegations of collusion between security forces and criminal organizations.’ [footnote 20]

8.3.5 Freedom House in its report covering events in 2022 observed ‘Gangs, many with ties to drug trafficking, also sway decisions at the subnational level.’[footnote 21]

8.3.6 The ICG report 2023 noted: ‘Street gangs, such as MS-13 and the 18th Street gang, at times partner with or work for drug trafficking groups that have penetrated the highest echelons of state. U.S. prosecutors believe that former President Hernández maintained mutually beneficial relations with various drug traffickers, even while supposedly leading an unstinting assault against them.’[footnote 22]

Updated to 6 October 2023

9. Organised criminal groups (OCGs), including gangs

9.1.1 The Global Organised Crime Index 2023, covering events in 2022, produced by the NGO, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GIATC), released 26 September 2023, stated:

‘Mafia-style groups operating in Honduras are involved in a range of criminal activities, such as drug trafficking, car theft, and extortion. The revenue generated from drug trafficking has contributed to the growth and sophistication of these groups. There are two main mafia groups in Honduras, both of which employ extreme violence and extortion to control the [MS-13 and Barrio 18] they operate in. Despite a recent decrease in domestic homicide rates, Honduras remains one of the most violent countries globally. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mafia groups in Honduras refrained from extortion, which allowed them to enter the political sphere by funding allies’ campaigns for municipal positions. Additionally, transportista groups, comprising family-based networks, assist mafia groups in criminal activities, such as transport logistics, cargo security, and money laundering.

‘Bribery and corruption play a significant role in organized crime groups’ operations, with deep political ties to local law enforcement and public officials facilitating their activities. Corrupt officials at different levels of government create opportunities for organized crime, and even construct infrastructure and transportation necessities for criminal entities. State security forces are involved in the arms and drug trafficking markets. In April 2022, a former president was extradited to the US for his involvement in drug and arms trafficking, as well as for using drug-related revenue for political campaign funding.

‘Foreign criminal entities, particularly Colombian and Mexican drug trafficking networks, operate in Honduras through small emissary groups located in large cities and border regions. These groups engage in drug production activities such as poppy cultivation and laboratory cocaine processing within Honduras, and subcontract Honduran transportista groups to facilitate the illicit transport of drugs northbound to the US via Guatemala. Central American and Chinese criminal networks are involved in local illicit activities such as human smuggling.

‘Private sector actors such as banks, insurance companies, and remittance companies play a considerable role in illicit activities, especially corruption, in Honduras, facilitating the flow of illicit revenue. Criminal entities often own or exploit the bank accounts of private sector businesses, such as hotels, to launder drug-related and other criminally sourced revenue. Additionally, business elites in Honduras have notable influence over the state judicial system, exacerbating corruption by manipulating legal processes to avoid the consequences of their actions.

‘Honduras-based criminal networks collaborate with other criminal groups, including state-embedded actors and foreign counterparts, to facilitate various organized criminal markets, such as drug trafficking, human trafficking, and arms trafficking. These networks diversify their activities by targeting transportista groups and stealing drug shipments along smuggling routes.’[footnote 23]

9.1.2 Dr J M Cruz and colleagues at the American Institutes for Research (AIR) & Florida International University (FIU) published a report on gang disengagement in Honduras in November 2020 (AIR/FIU) report 2020). The research is based on a survey with a sample of 1,021 respondents with a record of gang membership, and 38 in-depth interviews with former gang members and community members. Respondents were interviewed in prisons, juvenile detention centres, parole programes, rehabilitation centres and at faith based organisations between October and December 2019[footnote 24].

9.1.3 The AIR/FIU report 2020 noted: ‘MS-13 and Barrio 18 [also known as Pandilla 18 (or 18th Street Gang)[footnote 25]] are the dominant street gangs in Honduras, with MS-13 as the largest one.’ [footnote 26] Similarly, InSight Crime, a US think tank specialising in crime in Latin America, in its ‘Honduras profile’ updated February 2021, stated ‘… the primary gangs present in Honduras are MS13 and Barrio 18…’[footnote 27] The US State Department’s Overseas Security Advisory Council Honduras security report of July 2023 (OSAC CSR 2023) stated: ‘The MS-13 and Calle 18 gangs [Barrio 18] are the most active and powerful gangs present in Honduras.’[footnote 28]

9.1.4 The AIR/FIU report 2020 also noted ‘There are other, smaller gang groups … such as Vatos Locos, Los Chirizos, and El Combo que no se deja.’ [footnote 29] While the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) in a December 2022 report (ACCORD response 2022), citing various sources, stated:

‘According to a 2020 report by the United Nations Development Programme on the situation of maras and pandillas in Honduras in the year 2019, there is much more gang diversity in Honduras than in the other two countries in the Northern Triangle, El Salvador and Guatemala… Pamela Ruiz notes that the Honduran National Anti-Extortion Force (Fuerza Nacional Anti-Extorsión) identified 48 different gangs/criminal bands guilty of extortion, but the number includes “independent actors” … The following minor gangs are mentioned by several sources: Chirizos, El Combo que no se Deja, Los Benjamins… Los Tercereños, Vatos Locos, Olanchanos … Sources further mentioned other small gangs such as Los Ponce and Parqueños, however, virtually no information could be found on them. ’[footnote 30]

9.1.5 The ICG report 2023 noted: ‘Competition between [MS-13 and Barrio 18]… and other minor groups is fierce… Many of the smaller organisations are composed of just a handful of criminals, united by family ties, who alternately work for, ally with and fight the main outfits…’[footnote 31]

Updated to 6 October 2023

10. Structure and organisation of Mara Salvatrucha 13 and Barrio 18

10.1.1 The AIR/FIU report 2020 stated:

‘The two main Honduran gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18, have a clearly defined structure and organization, with specific roles and norms which regulate the activities and behavior of their members. Although gangs in Honduras do not seem to have a national leadership who would be recognized by all the groups, they have regional structures which are controlled from prisons. They organize their neighborhood cliques in sectores (sectors), which are overseen by regional leaders inside and outside prison. The MS-13 gang seems to be the largest and most organized of the gangs… both MS-13 and Barrio 18 are composed of regionally fragmented structures which operate in an autonomous fashion. Neither MS-13 nor Barrio 18 acknowledges a single national leadership council or individual leader in Honduras.’ [footnote 32]

10.1.2 The AIR/FIU report 2020 also noted: ‘The two main gangs in Honduras are composed of a collection of neighborhood groups, called cliques, with a close link to the territory in which they operate and orchestrate their criminal activities. These cliques are the basic gang unit and are made up of several members… [comprising of] regular members and collaborators or informants.’ [footnote 33]

10.1.3 According to AIR/FIU:

‘Regular members make up the core and muscle of the gang. They are in charge of carrying out most of the criminal and revenue-generating activities, such as extortions and drug dealing. Depending on the gang organization, they take different titles: soldier, paisa, paisa firme, gatillero, or traqueto. Collaborators or informants are not considered official members of the gang; they have not undergone an initiation rite, and they function as aides to the regular members. Their activities include communications, transportation of drugs and weapons, and surveillance, flagging the presence of strangers and potential rivals in the territory. Collaborators take different titles, which also may reflect a hierarchy within the group of collaborators: bandera, mula, aspirante, puntero, and colaborador…

‘Neighborhood cliques are grouped in sectores, which are the largest grouping level in the gang’s organization. Sectores are composed of several cliques which form a regional cluster, which usually involves a city or a region. Thus, as organizations, gangs in Honduras operate regionally. Each region or sector has a top leader, who usually is imprisoned and operates from any of the penitentiaries in the country. Those leaders are called Palabreros in the MS-13 organization and Toros in Barrio 18. They work in tandem with other leaders, who are outside prison, called Sargentos or Homies. These individuals oversee the activities of the cliques under their command on behalf of the imprisoned leader and themselves. One practice that both gangs observe and have in common is seniority. As explained by a former gang member who now leads rehabilitation programs in Honduras, “Seniority and loyalty to the gang is not only how [you] earn respect within the organization, but it is also how an individual can climb amongst the ranks of the organization.’[footnote 34]

10.1.4 Further detail about structure, organisation and roles with MS-13 and Barrio 18 is available pages 23 to 25 of the AIR/FIU report 2020 and pages 30 and 31 of the ACCORD report 2022.

Updated to 6 October 2023

11. Gang size and distribution

11.1 Size

11.1.1 The ACCORD response of December 2022, citing various sources, stated:

‘Regarding the numbers of gang members in Honduras the most current information that could be found is provided in an April 2016 report by InSight Crime and the ASJ. The authors also discuss that estimates vary widely and estimates of NGOs are considerably lower than official estimates by the Honduran police or the US Agency for International Development (USAID). While according to estimates by two NGOs the number of active gang members of both MS-13 and Barrio 18 together amounts to around 5,000 – 6,000, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) says Mara Salvatrucha has 5,000 and Barrio 18 has 7,000 members. The Honduran police contends that both gangs together have about 25,000 active… and according to a USAID report there are 36,000 active gang members in total …, but this number is of 2006 and it includes members of other Honduran gangs as well. An article by InSight Crime, published in 2012, speaks of some 1,340 MS-13 members in San Pedro Sula and some 410 members in Tegucigalpa …’ [footnote 35]

11.1.2 Human Rights Watch in their World report 2022 (HRW World report 2022) covering events in 2021 estimated that there were between 5,000 and 40,000 active gang members in Honduras although it is not clear where this information originated[footnote 36]. There were no up to date figures for gang members in the HRW World report 2023[footnote 37].

11.2 Location

11.2.1 There is limited accurate and detailed information in the sources consulted about the areas controlled by the 2 main gangs (see Bibliography).

11.2.2 The most recent detailed data is provided by InSight Crime in association with the Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa (ASJ Honduras), a Honduran civil society organisation promoting justice and changes towards a fairer society for the most vulnerable[footnote 38]. This paper publishd in 2016 stated:

‘Broadly speaking, gangs have little presence outside the three largest urban areas: the capital city of Tegucigalpa and its surrounding metropolitan area; the city of La Ceiba, the third largest in the country; and Cortes province. In Cortes, most gangs are concentrated in greater San Pedro Sula, the country’s industrial and economic capital. That is not to say that there is not gang presence in some rural areas. A prime example is the municipality of Tela, between La Ceiba and San Pedro Sula, where the MS13 has established a strong base of operations.

‘… gang presence in these cities gives no clear pattern of why gangs occupy certain territory and not others. According to police intelligence, the Barrio 18 is currently operational in approximately 150 neighborhoods, or “colonias,” in Tegucigalpa. As can be seen in the map below… Barrio 18’s largest extension of territory is in the southern part of the Capital District, including Tegucigalpa’s sister city, Comayaguela. Meanwhile, MS13 is operational in some… colonias in the capital district, while the gang’s largest concentration of forces is believed to be in the western part of the city. There are thought to be just 12 colonias out of 222 in which both gangs are present at the same time, including Tegucigalpa’s city center.

MS13 and Barrio 18 presence in Tegucigalpa

‘In San Pedro Sula,… meanwhile, Barrio 18 is present in 22 colonias. The MS13 is also present in 11 of those, explaining in part why the city sees so much violence, as the gangs jostle for dominance within these contested areas. In addition to those 11 colonias, the MS13 is present in another 58 colonias in San Pedro Sula. It should also be noted that other gangs are interspersed in both San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa…[footnote 39]

MS13 and Barrio 18 presence in San Pedro Sula

11.2.3 InSight Crime in its ‘Honduras profile’ updated February 2021 stated: ‘Gangs are concentrated in the country’s largest urban areas, including the capital Tegucigalpa, the economic hub of San Pedro Sula and the Caribbean coastal city of La Ceiba… or in rural areas close to the border with El Salvador, where they find a safe haven…[footnote 40]

11.2.4 The ACCORD response of December 2022, citing various sources, stated:

‘… maras are, according to the January 2020 publication by María Luisa Pastor Gómez, essentially an urban phenomenon. They are much more predominant in poor and marginalised neighbourhoods, where there is little state control (Pastor Gómez, 29 January 2020, p. 6). However, Elizabeth Kennedy [Central America Monitor Research Director for the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), social scientist and expert in Central American migration and indigenous and Garífuna People] disagrees with this statement and refers to interviews she has conducted with children and families from rural as well as from urban areas in 13 of 18 departments in Honduras, which showed that gangs operate in rural areas as well (Kennedy, 6 December 2022)

‘… The gang territories are marked by specific graffiti that adorns the walls of affected communities. Mostly the graffiti shows the numbers 18 for the Barrio 18 and 13 for the MS-13 (McGrath, 10 February 2021).’[footnote 41]

11.2.5 The Crisis Group report of 10 July 2023, based on 50 interviews with a range of sources, observed: ‘MS-13 and the 18th Street gang are prevalent mostly in suburbs of the capital Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, the country’s second largest city, but they are reportedly expanding into coastal regions and along the borders with Guatemala and El Salvador.’[footnote 42]

11.2.6 The USSD’s Overseas Security Advisory Council in its report on Honduras updated 18 July 2023 (OSAC report 2023) observed: ‘Hondurans continue to be affected by MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and Calle 18 [Barrio 18] gang activity in cities such as Tegucigalpa, Choloma, La Ceiba, Tela, and San Pedro Sula.’[footnote 43]

11.2.7 The HRW World report 2022 covering events in 2021 stated: ‘Gangs exercise territorial control over some neighborhoods and extort residents throughout the country.’[footnote 44] However, HRW do not provide detail or indicate how this information was obtained. HRW make no comment on gang control in their report on events in 2022[footnote 45]. The AIR/FIU report November 2020 noted that the smaller gangs - such as Vatos Locos, Los Chirizos, and El Combo que no se deja - had a limited reach compared to Barrio 18 and MS-13[footnote 46].

Updated to 6 October 2023

12. Profile of members

12.1.1 An AIR/FIU report November 2020 stated: ‘These organizations [Barrio 18 and MS-13] are composed of networks of turf-based groups of youth and adults.’ [footnote 47] The paper further noted:

‘… gangs remain a predominantly male phenomenon, and the average age at which males join a gang is 15. Interviewed females joined the gang at an average age of 13.2. Nearly 46 percent of the subjects interviewed for this study are active members of a gang, while the rest are in different stages of gang membership. Approximately 54 percent of the subjects interviewed in the survey belong—or have belonged—to Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), while 35 percent expressed their loyalty to the 18th Street Gang, also known as Pandilla 18 (or 18th Street Gang). The rest of the interviewees indicated membership in smaller gang groups: Los Chirizos, El Combo que no se deja, Los Olanchanos, Los Vatos Locos, etc.’[footnote 48]

12.1.2 Based upon 1,021 survey respondents, the November 2020 AIR/FIU research paper found that 94% of both current and previous gang members were male and 6% were female; 65% were under 26 years old and 15% were over 40. Women tended to be younger than men, with an average age of around 18 and 25 years respectively[footnote 49].

12.1.3 With regards to education, the AIR/FIU research paper found that a large majority of the survey respondents had not completed high school (90.3%) and 1.4% had never attended school. Gang members on average dropped out of school around 12-13 years old[footnote 50].

12.1.4 As to membership profile according to gender the AIR/FIU research paper stated:

‘The research team interviewed government officials, pastors, and leaders of organizations which work with former gang members. These interviewees said that while women used to play secondary roles in gangs, mostly as partners of gang members, there is no longer a significant gender difference in terms of gang affiliation and participation in gangs. Most former gang members in our sample shared the view that there are few differences between men and women with respect to their participation in gangs; many explicitly said they do not see any difference in terms of gender, noting that women can become more lethal than men because people tend to assume that women are not violent. One former Barrio 18 gang member from San Pedro Sula said, “Now gangs use women as hitmen (sicarias) because most people believe they are harmless, but when you give arms to women, they are lethal”…

‘Moreover, female gang members are often used for tasks traditionally associated with women’s roles, such as cooking for the gang members, attending to those who are injured and visiting them at the hospital, and doing errands, including sometimes transporting drugs from one place to another. Former female gang members whom we interviewed also said that women are used as sex objects to seduce or distract police officers during an operation.

‘Whether or not female gang members end up doing other jobs typically associated with men, data indicate that it is likely that the relationship between males and females in the gang is unequal and is consistent with the patriarchal or “macho” culture already prevalent in Honduras. Even former gang members who believed there were no differences between men and women in the gangs expressed the belief that women are “more passive” than men or that in the end, women are not the “head of the household and always obey the man.”’[footnote 51]

12.1.5 The InSight Crime profile updated February 2021 stated ‘…gangs like the Barrio 18 and MS13… concentrate their criminal activities in urban areas and recruit young people, many of whom are suffering from widespread economic inequality and a lack of opportunity.’[footnote 52]

12.1.6 The ACCORD response December 2022 citing various sources stated:

‘A 2020 analytical paper on Central American maras by María Luisa Pastor Gómez of the Spanish governmental Institute for Strategic Studies, explains that gang members join as young people: mostly boys, who come from broken and low-income families and who usually left school before the age of 16. These children seek an alternative space for socialisation and solidarity in a hostile environment. Some join to protect themselves or because they are forced to… With respect to female gang members, the paper adds that they tend to join around the age of 18, often to escape family problems and in approximately 12 percent of cases, because they are forced to do so… Joining a gang involves harsh and violent rites of passage.’[footnote 53]

Updated to 6 October 2023

13. Recruitment

13.1.1 The International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) in a thematic report ‘A web of violence – Crime, corruption and displacement in Honduras’ from March 2019, by Vickie Knox of London University, (IDMC paper 2019) stated:

‘Young people are particularly vulnerable to forced recruitment, which may start with grooming when children are given small gifts and attention in return for involvement. Boys are targeted from as young as six to act as lookouts, make deliveries and collect extortion money. Girls are targeted from the age of eight for sexual exploitation by the clika, and from 11 or 12 years to be sexually involved with a specific gang member… Forced recruitment in schools has triggered significant displacement. Gangs have infiltrated many education centres, particularly in urban areas, and pupils are targeted by their peers who try to convince them to become involved in gang activities. They must comply with the gang’s demands or leave…’[footnote 54]

13.1.2 The AIR/FIU report 2020 stated: ‘… being out of school may increase the vulnerability of some youths to gang membership, because they have few other alternatives, either for entertainment or for income generation.’ [footnote 55]

13.1.3 The AIR/FIU report described reasons for joining a gang:

‘Most survey respondents provided reasons for joining the gang which reflected the allure of the gang: They did so to be with peers and to be part of the organization. However, in-depth interviews revealed that beyond those reasons, youths were coming from problematic families, inattentive communities, and institutions which do not provide development opportunities to minors. In any case, gangs seem to represent a viable alternative to satisfying the emotional needs of individuals in their adolescent years. Gang leaders take advantage of this vulnerability and quickly push their members to criminal schemes and violence.’ [footnote 56]

13.1.4 The AIR/FIU report 2020 found:

‘… most of the [survey] respondents [of former and current gang members] did not undergo a process of initiation when joining the gang… In Honduras, only 31.8 percent of respondents with a history of gang affiliation said they joined through a process of initiation. Among female gang members, this percentage is even lower: 9.8 percent of the female respondents said they had to go through an initiation rite… rites of initiation were more common among the older respondents than among the younger ones.’ [footnote 57]

13.1.5 The AIR/FIU report added:

‘… although rites of initiation are not very common in Honduras, the largest and more powerful groups practice them much more frequently than the smaller gangs… The most common rite of “jumping into” the gang is for member initiates to take a beating from their own peers and future fellows in the gang… The survey also revealed that nearly 27 percent of the individuals who went through a formal process of initiation had to complete a “mission.” Those missions frequently entailed killing a person—or a few people—designated by the gang. In some instances, those missions involved the participation of more structured criminal schemes, such as setting up an extortion ring in a predetermined community. A comparison between gang organizations shows that although members of the MS-13 gang tend to endure more beatings as a form of initiation than Barrio 18 members, there is no statistically significant differences between the groups. The modes of joining the gang were very similar between the two largest gangs.’ [footnote 58]

13.1.6 With regard to women, the AIR/FIU report 2020 stated:

‘Although men and women allegedly have similar roles in the gangs, most women are sexually abused once they are in a gang. This happens sometimes as part of their initiation ritual, wherein all members of the clique rape the woman before she can be admitted. Often women are abused only because members of the gang want to have sex with them. As one former Barrio 18 gang member from San Pedro Sula said, “If several members of the gang want to have sex with a woman, so long as she is not committed in a relationship to someone in the clique, she cannot refuse” …’ [footnote 59]

Updated to 6 October 2023

14. Leaving a gang

14.1.1 TheAIR/FIU report 2020 stated:

‘Intentions to leave the gang are more frequent in the early stages of membership. Those intentions decline for a while and then increase again with age. Successful disengagement is closely associated with interactions that provide social and instrumental support to reintegration.

-

‘Members of the two major gangs (MS-13 and Barrio 18) express less intention of disengagement than members of the smaller gangs or combos…

-

‘There is a U-shaped curve relationship between the number of years in the gang and intentions to leave. During the first years of gang membership, intentions to leave are stronger; then they subside for a while and start growing again after six years of being in the gang. This pattern suggests that the early months and years of gang life are probably full of doubts about membership. These doubts are later quenched by gratifying experiences as a gang member and then reemerge as the individual matures.

-

‘Religion also plays a critical role in the process of leaving the gang. Belonging to an Evangelical church in Honduras contributes to one’s intention to disengage from the gang and provides safe passage out of the group.

-

‘Non-gang groups and social networks of non-gang members are key to supporting gang members’ intentions to leave the gang. Active members who spent the most time with non-gang individuals (their family and non-gang friends) were more likely to disengage from the gang.’[footnote 60]

14.1.2 The AIR/FIU report added:

‘Respondents said it is easier for a lower ranking gang member to get permission to leave the gang or to disengage from gang activities; respondents said lower ranking members are less likely to pose a threat to the gang or reveal information to rival gangs or the police. In contrast, the path to disengagement is difficult for someone who ranks higher in the gang… As with men, women who ascend to positions of leadership in the gang have a more difficult time disengaging from the gang than those who are not leaders. Having more authority and decisionmaking capacity in the gang gives them greater access to information, which top gang leaders regard as one of the most valuable assets.’ [footnote 61]

14.1.3 With regards deserting a gang, the AIR/FIU paper stated:

‘Deserters are threatened with murder, and anyone who wants to leave the gang needs to obtain special permission from the top leadership. In a case described in a qualitative interview, a female former gang leader said she had to obtain a special permit to leave the gang. She explained that she was granted the permit because she was pregnant, and she said she was committed to God; however, the gang leader made it clear to her that “if it is true that you are attached to God, you have to keep your devotion, because the minute you detach yourself, I will give the order to kill you.”’ [footnote 62]

14.1.4 The AIR/FIU report noted: ‘Pastors and experts indicated that gangs would track former members as they integrated into a community of faith to ensure they did so “with sincerity”; the gang respected one’s decision to leave for religious reasons, but potentially would retaliate against those whom they determined were not following a religious lifestyle…’ [footnote 63]

14.1.5 The AIR/FIU report stated:

‘Despite the difficulties associated with leaving a gang, many people are successful in leaving the gang in Honduras. In fact, nearly half of our survey sample were no longer active in the gang and see themselves as former gang members. In addition, most respondents (62 percent) know someone who has done so… These numbers suggest that in general, cases of disengagement are relatively frequent..’ [footnote 64]

14.1.6 The table below[footnote 65] is based on information from the AIR/FIU paper on what an individual has to do to leave a gang.[footnote 66]

| Mechanisms of leaving the gang | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Impossible to leave | 37% |

| Join church or rehab programme | 28% |

| Talk to leaders | 19.4% |

| Just leave | 11.9% |

| Accomplish a mission (usually understood as killing someone) | 2.7% |

| Other | 0.9% |

14.1.7 The ACCORD response December 2022 citing María Luisa Pastor Gómez of the Spanish governmental Institute for Strategic Studies who spoke about leaving a gang:

‘“Once in [a gang], the new members accept a series of strict rules and values and find themselves forced to develop strong ties of belonging, unity, loyalty and solidarity with the new ‘family’ while simultaneously weakening their links to their own families and to society. In principle, joining a gang is an irreversible process, as the leaders do not allow anybody to leave, unless this is achieved through joining some evangelical church”…

‘“If done without permission [leaving a mara]… implies certain death, and obtaining the leaders’ blessings involves long and arduous negotiations… Many departures take place via religious conversion and integration into an evangelical church, an experience which provides a safe haven that allows aspiring deserters to reestablish links with the community, to build their families and to look for educational or job opportunities without harassment from the gang. However, this way is not easy either, as any members wishing to leave the Mara are subjected to very close monitoring… Other challenges faced when leaving a gang are the total lack of the skills needed for regular work, the lack of training opportunities, the constant threat emanating from old gang rivals, harassment from the police and security forces, and social discrimination on account of their past and their appearance, since one of the most visible features of Mara members until recently were their tattoos, which are almost impossible to get rid of.”…’[footnote 67]

Updated to 6 October 2023

15. Gang activities - control of territory

15.1.1 The IDMC report 2019 stated: ‘Street gangs’ territorial control extends to all people within their area, and particularly women and girls… The territorial control that organised crime groups exert over border areas means that women and girls who live there are also vulnerable to human trafficking and forced prostitution as well as sexual abuse by the groups’ members…’ [footnote 68]

15.1.2 The AIR/FIR report November 2020 stated:

‘Gang activities revolve around the concept of territorial control. All gangs seek to exert control inside the communities in which they operate in order to extract resources and revenues. Both the MS-13 and 18th Street gangs use violence and participate in similar criminal activities… local drug trafficking, extortion, and assassination for hire, among others. However, most testimonies provided during the in-depth interviews coincide with the notion that MS-13 gang members concentrate their criminal activities around the control of drug markets, while Barrio 18 gang members focus more on extortion activities which directly affect the communities in which they operate.’ [footnote 69]

15.1.3 The AIR/FIU report 2020 also noted:

‘… As one former MS-13 gang member explained, Mara Salvatrucha will do everything in their power to keep the police from entering their territories. When a community member has a problem inside MS-13 gang territory, people go to the gang leaders before contacting authorities to solve the problem. These findings are consistent with past research which indicates that MS-13 gang members stopped extorting inside their neighborhoods to leverage support with the people who live in those communities. Regardless, MS-13 gang members are violent and constantly engaging in criminal behavior.’[footnote 70]

15.1.4 The InSight Crime profile updated February 2021 stated: ‘[Barrio 18 and MS13]… often exert influence over entire neighborhoods, imposing their own order, demanding extortion payments from businesses and residents, and running local drug sales and kidnapping rings.’ [footnote 71]

15.1.5 ACCORD in their response of December 2022 gangs report citing a September 2022 publication by the Global Protection Cluster stated:

‘… territorial control by the maras is reflected in the imposition of invisible borders, in curfews and dress codes. All persons living in gang-controlled areas face restrictions in accessing the rights to health, education, work and the use of public spaces. The publication further notes that territorial disputes in areas historically impacted by violence, such as San Pedro Sula, La Lima, Choloma and Tegucigalpa as well as in areas where the level of violent incidents was historically lower, such as Danlí, Choluteca, Olancho, Valle, La Ceiba and Gracias a Dios, have intensified. Controls and restrictions imposed by the maras have increased in recent years, especially in peripheral areas of urban centres, where restrictions on mobility have worsened.

‘France 24, a French state-owned international news television network that also broadcasts in Spanish, in July 2022 publishes an article on such an invisible boundary. The article describes a dirt road that separates the territories of MS-13 and Barrio 18 in the Chamelecón neighbourhood, a hotspot for gang violence in San Pedro Sula… The dirt road is known as “la frontera” and in July 2022 was crossed by members of Barrio 18, who fired machine guns on a street and demanded of locals living on the MS-13 side to vacate the area. Ten families had to leave, and even though the police reinforced their presence, they didn’t return’ [footnote 72]

15.1.6 The ACCORD response of December 2022, in an interview with María Luisa Pastor Gómez of the Spanish governmental Institute for Strategic Studies, stated:

‘“Gangs are groups that create their own rules and membership criteria and that are marked by an obsessive territorial logic. The territorial framework —usually a marginal neighbourhood or a hill— is their place of action which they consider their property. Mara members fight to maintain control over their physical space and defend it to the last. They even impose restrictions on the movement of its inhabitants, often according to the territorial limits established with the rival gang. Maras secure the support of local gang family members and also rely on “falcons” or informers who act as their eyes and ears inside the neighbourhoods and supply them with all information. …The Maras impose tacit codes of conduct on inhabitants, and if the latter reject those, they suffer violence. Refusing to collaborate also means death, as does accidentally trespassing on a rival gang’s territory. Gang members lay down the rules in the communities. People can see and hear, but they must never speak about or report anything or they risk being tortured or, in the worst case, murdered. At night, vehicles trying to enter the neighbourhoods must switch off their lights, otherwise they can come under fire. If a person wants to move between neighbourhoods, they must request a permit and pay 5 dollars. Everyone is asked to produce their ID, and there are even rules regarding clothes. For example, wearing a Tshirt with the number 18 in a neighbourhood controlled by the MS13 Mara can be a reason to die.” …’ [footnote 73]

15.1.7 A UNHCR report from March 2022 stated:

‘Community leaders reported incidents of housing dispossession and occupation by street gangs, resulting in the forceful displacement of families or, in the case of San Pedro Sula, preventing people affected by Eta and Iota hurricanes to return to their place of origin. In San Pedro Sula, communities stressed major loss of income, assets, community spaces, while elders and community leaders expressed unusual fear over crossing “invisible borders”…

‘Chamelecón is one of the largest sectors of San Pedro Sula and is made up of 62 colonies. The sector has historically suffered from the impact of violence and territorial control of two gangs over northern and southern areas of the sector, causing many families to abandon their homes in search of safer communities.

‘Choloma is a municipality in the Department of Cortés, located on the outskirts of San Pedro Sula…. The situation of generalized violence is mainly caused by fragmented street gangs that frequently dispute territories to maintain strategic control over drug trade and the road to the main national port of Omoa. The violence affects disproportionately children, youth, and women, making it one of the municipalities with the highest femicide rate in Honduras.’[footnote 74]

Updated to 6 October 2023

16. Gang activities - drug trafficking

16.1.1 The AIR/FIU report 2020 noted ‘The MS-13 gang… tend to specialize to a larger extent in local drug trafficking and assassinations for hire. They tend to operate with more consideration for the community in which they are based, and they are more effective in penetrating criminal justice institutions for their own advantage.’[footnote 75] The same report stated ‘In the in-depth interviews, former MS-13 gang members explained that their organization focuses on petty drug trafficking and maintains a good relationship with the people within their neighborhoods.’[footnote 76]

16.1.2 The ICG report 2023 noted:

‘… street gangs, such as MS-13 and the 18th Street gang, at times partner with or work for drug trafficking groups that have penetrated the highest echelons of state… The country’s most widespread criminal activities are drug trafficking and extortion… A peculiarity of Honduran gangs compared to those in other Central American countries is their apparent prominence, particularly the MS-13, in drug smuggling… Once controlled by a few cartels, drug trafficking in Honduras is now run by myriad groups, including gangs… Some of these groups reportedly hold a tight grip over remote parts of the country, particularly La Mosquitia, a stretch of land along the eastern coast, and are responsible for some 30 per cent of the country’s violent deaths, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime… They also seem to be trying hard to turn Honduras from a transit country into a cocaine producer. In 2022, authorities eradicated approximately 140 hectares of coca, more than thirteen times the previous year’s total. This area is but a fraction of that under cultivation in Colombia, but the rise suggests an effort to concentrate both production and trafficking in Honduras…‘[footnote 77]

17. Gang activities - violence

17.1 Use of violence

17.1.1 An AIR/FIU research paper from November 2020, citing other sources, stated: ‘Despite the difficulties in pinpointing the precise number of active gang members in Honduras, government officials and experts view street gangs as responsible for an important share of the criminal violence taking place in the country. However, as with the number of gang members, there are no reliable data about the number of murders and crimes committed by gangs in the country.’[footnote 78] The same AIR/FIU report stated: ‘As with the gang-related statistics, scholars and journalists interviewed by the research team maintained that the data [on murder rates] are not completely reliable. More importantly, however, the gang problem in Honduras continues to be severe, even with the reduction in homicide rates.’ [footnote 79]

17.1.2 The OSAC CSR 2023 stated: ‘The MS-13 and Calle 18 gangs [Barrio 18] are the most active and powerful gangs present in Honduras. Gangs are not reluctant to use violence, and specialize in murder-for-hire, carjacking, extortion, and other violent street crime… Drug trafficking and gang activity are the main causes of violent crime in Honduras.’ [footnote 80]

17.1.3 The InSight Crime homicide round-up for 2022, dated February, 2023 stated ‘Many of the violent deaths in Honduras are attributed to gangs known for retail drug trafficking and extortion.’ [footnote 81]

17.1.4 The USSD’s OSAC report 2023 noted: ‘Drug trafficking and gang activity are the main causes of violent crime in Honduras… Major cities (e.g., Tegucigalpa, San Pedro Sula, La Ceiba) have homicide rates higher than the national average, as do several Honduran departments… including Atlántida, Colón, Cortés, and Yoro.’[footnote 82]

17.2 Homicide statistics

17.2.1 The InSight Crime profile updated February 2021 identifies Barrio 18 and MS13 as the primary drivers of homicide[footnote 83].

17.2.2 The table below has been created by CPIT based on data presented by UNODC and InSight Crime but drawn from Honduran government sources. It documents the intentional homicide rate in Honduras between 2010 and 2022:

| Year | Women | Men | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 9.21 | 136.88 | 73.79 |

| 2011 | 11.33 | 151.81 | 82.39 |

| 2012 | 13.95 | 147.65 | 81.57 |

| 2013 | 11.05 | 131.11 | 71.77 |

| 2014 | 10.98 | 116.89 | 64.54 |

| 2015 | 10.41 | 99.37 | 55.39 |

| 2016 | 9.96 | 97.85 | 54.44 |

| 2017 | 8.21 | 71.21 | 40.14 |

| 2018 | 7.64 | 67.45 | 37.87 |

| 2019 | 8.06 | 73.13 | 40.95 |

| 2020 | 6.51 | 64.23 | 35.7 |

| 2021 | 6.47 | 69.3 | 38.25 |

| 2022 | 38.5 |

17.2.3 The InSight Crime homicide round-up for 2022 dated February 2023 stated: ‘Honduras continued its streak as Central America’s deadliest country in 2022, with a homicide rate of 35.8 per 100,000 people, according to government figures. Nonetheless, the country reduced homicides by 12.7% compared to 2021. The government has not registered such a low number of deaths since 2006, according to a statement from the Security Ministry….’ [footnote 86]

17.2.4 The Infosegura, a regional strategic partnership of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) for policymaking and implementation, provided data for 2022 noting

-

‘Homicides decreased by 12.8% in 2022 with regard to the previous year.’

-

‘… a homicide rate of 35.8 per 100,000 population, which is the lowest in the last decade.’

-

‘45% of homicides are associated with social conflict and other causes not attributable to organized crime.’

-

‘40% of homicide victims are between 18 and 30 years old.’

-

‘145 municipalities [out of 298] reduced the number of homicides.

-

‘34 municipalities maintained the same number of homicides…

-

‘44 municipalities [had]… zero homicides.’[footnote 87]

17.2.5 An Infosegura report on citizen security in 2022 provided detail about change in homicide rates and distrubution between 2021 and 2022[footnote 88].

17.2.6 The Infosegura report provided data on violence and citizen security between January and June 2023 (Infosegura report 2023) based on preliminary data from Technical Board on Violent Deaths: National Police, Public Prosecutor’s Office/Directorate of Forensic Medicine, National Registry of Persons, Observatories of Coexistence and Citizen Security, National Institute of Statistics, Undersecretariat of Security in Police Affairs and the Technical Unit for Inter-institutional Coordination (UTECI). The report stated:

-

there were 1,639 homicides in the first half of 2023 – the number of homicides in same period in 2021 was 2,059 in 2021 and in 2022 was 1,900

-

86% of homicide victims were men

-

37.4% homicide victims were aged 18 to 30[footnote 89]

17.2.7 The Infosegura report 2023 provided the graphic and map below[footnote 90] describing the number of homicides by municipality between January and June 2023:

81 municipalities report no homicides.

203 municipalities report between 1 and 20 homicides.

The municipalities with most homicides are Distrito Central y San Pedro Sula.

1,191 homicide cases (72.7%) in the municipalities with OMCSC observatories.

222 municipalities where there are no registered homicides of women.

85 municipalities where there are no registered homicides of men.

NB OMCSC stands for Municipal Observatories of Coexistence and Citizen Security of the Secretariat of Security.

17.2.8 The Infosegura report 2023 also provided the chart below of municipalities with the highest number of homicides:

| Municipality | Number of violent deaths | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Distrito Central | 220 | 14% |

| San Pedro Sula | 124 | 8% |

| Choloma | 70 | 4% |

| Tocoa | 56 | 3% |

| Puerto Cortes | 43 | 3% |

| Comayagua | 43 | 3% |

| Olanchito | 37 | 2% |

| Catacamas | 37 | 2% |

| Danlí | 37 | 2% |

| Juticalpa | 36 | 2% |

17.2.9 The ICG report 2023, however, noted ‘… the growth of extortion may have intensified violence in at least some places, as rival gangs battle for turf… Though authorities report a reduction in homicides nationwide, murder rates increased in six of the country’s eighteen departments… Mass killings – often involving attacks by one gang on another – have continued unabated, with 50 recorded in 2022, taking 185 lives altogether… One recent massacre in a pool hall in Choloma claimed the lives of thirteen people…’

Updated to 6 October 2023

18. Gang activities - extortion

18.1 Prevalence

18.1.1 The AIR/FIU report 2020 observed ‘the Barrio 18 gang seems to be more focused on extorting their own communities [than MS13], and they tend to use violence more frequently to enforce their threats.’ [footnote 92]