Guide to Insolvency Statistics

Updated 30 April 2024

1. Introduction

This document provides a guide to insolvency, focusing on concepts and definitions used in statistics published by the Insolvency Service.

The areas covered in this guide are:

-

high-level descriptions of the types of insolvency which apply to companies and people;

-

the data recorded and any associated data quality issues; and

-

legislation coming into effect in the period covered by the statistics, which may affect comparisons over time.

Further information on statistics published by the Insolvency Service can be found in:

- the Publication Schedule, which provides information on the upcoming releases of Official Statistics

- the Methodology and Quality documents published alongside each Official Statistics release, which describe how the statistics were produced, note any limitations or caveats, and assess the quality of the statistics,

- the Revisions Policy, which sets out the Insolvency Service’s policy for planned and unplanned revisions to the data; and

- the Data Quality Assurance and Audit Arrangements, which documents the data quality procedures for each stage of the production of the statistics.

The Insolvency Service welcomes feedback on this guide. Please send comments to [email protected].

2. Insolvency Service statistics publications

The Insolvency Service produces Official Statistics as described below.

2.1 Monthly insolvency statistics

Monthly company and individual insolvency statistics are published approximately two to three weeks in arrears of month end. Numbers are provided for England & Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The company statistics include information about numbers of insolvency by type of insolvency procedure, as well as the rate of insolvency (i.e. what proportion of companies on the effective Companies House register entered insolvency in a given 12-month period). A long-run CSV file is provided with information back to 2000 (where available). For some insolvency types, information back to 1960 is available in the Insolvency Statistics Archive. Breakdowns of numbers of insolvency by industry are also provided. Additional detail on industry breakdowns by insolvency procedure are provided on a quarterly basis only. The underlying record-level data is also published, providing a list of all company insolvencies over the past eleven years. The numbers in the publication tables can be derived from this record-level data.

The individual statistics include information about numbers of insolvency by type, as well as the rate of individual insolvency (i.e. what proportion of adults in England & Wales became insolvent in a given 12-month period). Breakdowns of bankruptcy by petition type and employment status (self-employed or other) and numbers of income payment orders and agreements are also included. A long-run CSV file is provided with monthly information back to 2000 (where available). A file with quarterly information back to 1984 is also available. For some insolvency types, information back to 1960 is available in the Insolvency Statistics Archive. Breakdowns of numbers of trader bankruptcy by industry are provided in separate Excel tables.

Underlying data for these monthly statistics for England and Wales were adjusted using an ARIMA model where there was evidence of seasonality. This removal of systematic calendar-related variation enables comparisons to be made between months and the underlying trend in insolvency numbers to be determined. Details can be found in the annual Seasonal Adjustment Review.

This official statistics publication is a successor to the previously published quarterly insolvency statistics, which were accredited official statistics. As of April 2024, the Office for Statistics Regulation was assessing this new publication for compliance with the standards of trustworthiness, quality and value in the Code of Practice for Statistics. Because the review is ongoing, this edition of the publication is labelled as ‘official statistics’ instead of ‘accredited official statistics’.

2.2 Individual insolvency by location, age and gender statistics

Individual insolvency statistics by location, age and gender are published annually. They provide the annual number of bankruptcies, debt relief orders (DROs) and individual voluntary arrangements (IVAs) in each country, region, county, local authority, electoral ward and parliamentary constituency in England & Wales for each of the past ten years. For the latest year, breakdowns are also provided by age and gender down to local authority and parliamentary constituency level.

Location, age and gender statistics are only provided for individual insolvency. The Insolvency Service does not hold accurate information on the location of companies. This is because the address often reflects the location of an insolvency practitioner handling the case, rather than the location where the company traded before it became insolvent. Even where this is not the case, the registered office address with Companies House may not reflect the primary trading location of the company.

2.3 Individual voluntary arrangements outcomes and providers statistics

Statistics on the outcomes and providers of IVAs in England & Wales are published annually.

These include:

-

The number of IVAs registered in each year since 1990, broken down by whether they are ongoing, completed or terminated

-

The percentage of IVAs registered in each year that terminated, broken down by the length of time between approval and termination

-

The number of IVAs registered by provider

IVA termination rates by firm are not currently published because of complexities relating to the transfer of IVAs between firms, particularly where an IVA provider ceases trading and their ongoing IVAs are transferred to another firm. This creates a bias, as a firm receives a number of IVAs which have been ongoing for many years and are therefore more likely to complete successfully. The Insolvency Service statistics team is currently working through these issues with a view to publishing this information in the future.

3. Company insolvency in the United Kingdom

This section relates to the United Kingdom. Company insolvency is mostly the same across the United Kingdom, but differences in Scotland and Northern Ireland have been identified where appropriate.

Company insolvency applies to incorporated companies (including limited liability partnerships) – a specific legal form of business that is registered at Companies House. Company insolvency (being unable to pay creditors the money they are owed) can be dealt with through a variety of legal processes, including liquidation (which results in the company ceasing to exist); or through company rescue procedures such as administration.

The Insolvency Statistics cover five formal company insolvency procedures: compulsory liquidation; creditors’ voluntary liquidation; administration; company voluntary arrangement; and receivership. The numbers of moratoriums and restructuring plans, which are rescue procedures used by companies facing financial difficulties, are included in the commentary, but not in the data tables.

Non-insolvent companies can also close through dissolution or through members’ voluntary liquidation (MVLs). These are counted in Companies House statistics, which showed that in the 2023/24 financial year, there were 9,240 MVLs and 663,345 companies were dissolved. There were 23,263 insolvent liquidations in the same period, which is 3.5% of the number of dissolutions.

Data on compulsory liquidations in England and Wales are sourced from administrative records of the Insolvency Service, which manages the case administration process, though responsibility sometimes passes to licensed insolvency practitioners. Data on compulsory liquidations in Northern Ireland are sourced from administrative records of the Department for the Economy in Northern Ireland. Data on all other company insolvencies are sourced from Companies House, which is required by law to be notified of all company insolvencies.

3.1 Types of company insolvency

Liquidation is a legal process in which a liquidator is appointed to ‘wind up’ the affairs of a limited company. The purpose of liquidation is to sell the company’s assets and distribute the proceeds to its creditors. At the end of the process, the company is dissolved – it ceases to exist. There are two main types of liquidation procedure:

- Compulsory liquidation – the court makes a winding-up order on the application of a creditor, shareholder or director.

- Creditors’ voluntary liquidation (CVL) – shareholders of a company can themselves pass a resolution that the company be wound up voluntarily.

In either case they are said to have been wound up. A third type of winding up, members’ voluntary liquidation (MVL), is not included in Insolvency Service statistics because it does not involve insolvency – all debts are paid in full. Companies House produces statistics on MVLs.

Administration is when a licensed insolvency practitioner, ‘the administrator’, is appointed to manage a company’s affairs with a view towards achieving certain statutory objectives. The primary objective of administration is the rescue of the company as a going concern, or if this is not possible the administrator will try to achieve a better result for creditors than would be likely if the company were to be wound up. Finally, if neither of these can be achieved, the administrator will seek to realise company property in order to make payments to one or more secured (and in some cases preferential) creditors.

Company voluntary arrangements (CVAs) are also designed as a mechanism for business rescue. They are a voluntary means of repaying creditors some or all of what they are owed. Once approved by 75% or more of creditors, the arrangement is binding on all creditors (although secured creditors retain their security rights). CVAs are supervised by licensed insolvency practitioners.

Administrative receivership is where a creditor with a floating charge (often a bank) appoints a licensed insolvency practitioner to recover the money it is owed. There are other types of (non-insolvency) receivership appointments, for example under the Law of Property Act 1925. Administrative receiverships are now rare, because the use of this procedure is restricted to certain types of company, or to floating charges, created before September 2003. The methodology for counting receiverships has changed – before 2000, all types of receivership were included in the statistics as it was not possible to distinguish between insolvent and non-insolvent receivership appointments, so these figures should be treated with caution. Currently, the vast majority of receivership appointments are of the non-insolvency type, but only insolvent receiverships are counted in the statistics.

Companies can be in more than one type of insolvency at the same time (for example receivership and CVA), or can move from one form to another (for example administration to CVL).

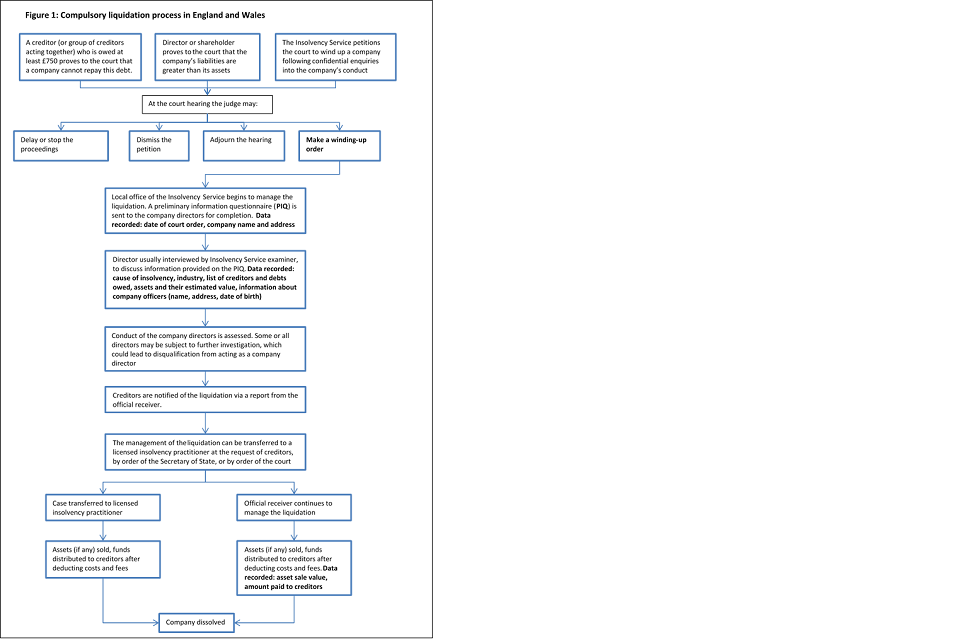

3.2 Compulsory Liquidation

Compulsory liquidation commences on the making of a compulsory winding-up order by the court. Its purpose is to collect the company’s assets and distribute them to its creditors. Winding-up orders are usually made on the petition of a creditor, shareholder or director, but a petition can also be presented by the Secretary of State for the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), or by the Financial Conduct Authority, on the grounds of public interest.

Once a winding-up order is made, a liquidator will manage the case – either the official receiver (an officer of the court) or a licensed insolvency practitioner (IP). The company’s assets are sold by the liquidator, who distributes the proceeds to creditors after the fees and costs of the liquidation are deducted. Once this is completed, the company is dissolved (ceases to exist).

A simplified summary of the compulsory liquidation process in England and Wales is summarised in Figure 1 below.

Source: Insolvency Service

Key data recorded by the Insolvency Service about compulsory liquidations

The event of liquidation: The Insolvency Service receives information from the court when the winding-up petition is first presented, and when the court order is made. The Insolvency Service is notified of all compulsory liquidations in England and Wales, so numbers of these cases recorded in insolvency statistics should be complete. The date of the court order is used in compiling the statistics, as opposed to the date the information is received from the court or entered onto ISCIS (the Insolvency Service’s electronic case management system). On occasion, information is received from the court after the cut-off period for extracting data for the monthly publication. Numbers for previous periods are revised in the statistics when late information is captured.

Industry Sector: The preliminary information questionnaire (PIQ) records the type of work carried out by the company. The examiner selects an industry code based on the 2003 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codings. While the harmonised standard for industry classifications is currently the 2007 SIC, the Insolvency Service’s administrative systems do not currently support this standard.

This information is used in the Insolvency Statistics, but is not complete. In some cases, industry is recorded as “unknown”. In 2023, approximately half of companies entering compulsory liquidation had their industry classified as “unknown”, and the quality of data which is recorded relies on information being correctly entered into ISCIS.

Changes to the industry classification used on ISCIS were made between Q3 and Q4 of 2006. As a result of this change, industry breakdowns published in the current statistical tables are not consistent with previously published editions that cover 2006 and earlier.

Cause of insolvency: The official receiver has a statutory duty to investigate the cause of failure of a company in compulsory liquidation. The PIQ asks for the reason why the company became insolvent, in the director’s own words. Based on this information and/or the interview (if held), the examiner records the cause of insolvency, using a coding frame (for example, ‘excessive borrowing’, ‘failure to deal with tax affairs’, ‘loss of market’, ‘bad debts’). This information is not currently considered suitable for use in Official Statistics.

Assets: All assets (the liquidation estate) vest in (become the responsibility of) the liquidator in order that they can be realised (sold); the director is required to disclose all assets. The director makes an estimate of the value of each of their assets, which is recorded on ISCIS. Separately, the examiner records estimates of the realisable value (likely sale price) of each asset. Both of these estimates are subjective, and are often recorded to the nearest round number, or as zero.

When assets are sold, the realised amount (actual sale price) is recorded. In most cases, there are little or no assets in the estate, but for those cases with substantial assets (such as property) it can take a long time – sometimes several years – to complete the sale of assets. Where an IP (rather than the official receiver) is the liquidator, information on realised amounts is not recorded against individual assets on ISCIS. Information on the value of assets in compulsory liquidation is not currently considered suitable for use in Official Statistics.

Debts and creditors: The director lists the company’s known creditors and the estimated amount owed to each in the PIQ. If an interview takes place, this is discussed with the examiner. The official receiver sends a report to creditors which lists the debts owed, often grouped by type of debt. Creditors are asked if they wish to make a claim on the estate (wish to share in the money recovered from selling assets). To do this, creditors send a proof of debt to the liquidator. The amount of debt claimed is recorded for each creditor, which may be different from the amount estimated by the director (who may, for example, have not included any interest payments). However, in most compulsory liquidations, there is no distribution to creditors because there are little or no assets in the estate. It is common, therefore, for creditors not to make a claim.

The value of debts in compulsory liquidation is not currently considered suitable for use in Official Statistics.

Legislative changes

Compulsory liquidation is dealt with under the Insolvency Act 1986. A quarterly time series of compulsory liquidations in England and Wales is available from 1960.

Differences in Scotland and Northern Ireland

The process in Northern Ireland is similar to England and Wales, and is dealt with under the Insolvency (Northern Ireland) Order 1989. Data are sourced from the Department for the Economy.

In Scotland, compulsory liquidation is dealt with under the Insolvency Act 1986. The Accountant in Bankruptcy (AiB) is responsible for recording information about company liquidations in Scotland on the register of insolvencies. It does not itself act as liquidator: all compulsory liquidations are administered by licensed insolvency practitioners. For Insolvency Service statistics, compulsory liquidation data for Scotland are sourced from Companies House.

3.3 Other forms of company insolvency

All other forms of company insolvency are administered by licensed insolvency practitioners. By law, company insolvencies must be reported to Companies House, which maintains the Register of Companies and updates it with information about insolvency. All compulsory liquidations are also reported to Companies House, but the Insolvency Service uses its own administrative data to produce statistics on these cases.

The insolvency practitioner provides Companies House with certain statutory documents, such as:

- The event of insolvency;

- Appointment of insolvency practitioner (including changes or additions);

- A Statement of Affairs (detailing among other things the company’s assets, liabilities and circumstances of the insolvency);

- Regular progress reports;

- The end of the insolvency (for example exit from administration, dissolution, end of a CVA);

Receipt of the documents is recorded by Companies House on its database, and the documents are scanned and stored in their database. The type of form and the date received are recorded on the system, but in most cases the content of the form is not input on the database - one exception is the name and address of the insolvency practitioner(s) administering the insolvency.

This means that much of the data about company insolvency – such as debts, assets and payments to creditors – is not accessible other than by downloading and viewing individual documents.

Legislative changes and other factors

The methodology for producing company insolvency statistics changed following a consultation in 2015. A monthly time series using the current methodology is available back to 2000. Comparisons with numbers in archived statistics from before this date should therefore be treated as approximations rather than exact.

In particular:

- CVLs may have been under-counted under the old methodology, which counted a specific form filed at Companies House which is not always submitted at the beginning of an insolvency;

- Administrations were sometimes counted more than once under the old methodology, because the appointment of additional or replacement administrators was counted as a new insolvency;

- Receiverships were sometimes counted more than once under the old methodology, because the appointment of additional or replacement receivers was counted as a new insolvency; and

- Receivership statistics prior to 2000 included forms of receivership that are not insolvencies.

CVLs are dealt with under the Insolvency Act 1986. A time series of CVLs in England and Wales is available back to 1960.

Administrative Receiverships are dealt with under the Insolvency Act 1986. However, before 2000, the Insolvency Statistics also include other types of receivership appointments, for example under the Law of Property Act 1925. Under the old methodology, because the same statutory documentation was used for all receivership appointments, it is not possible to break them down into different types before 2000. A time series of receivership appointments (inclusive of non-insolvency appointments) in England and Wales is available back to 1987. A time series of administrative receiverships is available back to 2000. A time series of non-insolvent receiverships is not available.

CVAs and Administration Orders are dealt with under the Insolvency Act 1986, and a time series for these cases in England and Wales is available back to 1987.

The Enterprise Act 2002 introduced revisions to the corporate administration procedures, replacing Part II of the Insolvency Act 1986 with Schedule B1. These include the introduction of additional entry routes into administration that do not require the making of an Administration Order and a streamlined process for administrations whereby a company can in some circumstances be dissolved without recourse to liquidation. Following this legislation, Administration Orders quickly became rare. Administrations under the Enterprise Act have been included in the Insolvency Statistics since 2003 Q3,

Since the changes under the Enterprise Act, is has also been possible to identify when companies move from administration into CVL. These are excluded from the headline figure for CVLs in the Insolvency Statistics, as they do not represent a “new” insolvency. They are however included in a separate table for completeness, and are used to calculate the total liquidation rate.

The Enterprise Act also restricted the appointment of administrative receivers to companies where charges were created before September 2003, and to eight types of corporate insolvency. Administrative receiverships are now rare.

3.4 Restructuring plans and moratoriums

The Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 created two new procedures:

- Restructuring plan: An agreement between a company facing financial difficulties affecting its ability to carry on business as a going concern, and its creditors. A court can sanction a restructuring plan if it is fair and equitable, with the agreement becoming binding on all creditors.

- Moratorium: A period during which no creditor can take action against a company without court permission. While moratoriums are overseen by an insolvency practitioner (the monitor), the directors continue to run the company.

Differences in Scotland and Northern Ireland

In Scotland, policy on administrations and CVAs is reserved to the UK Government, and the procedures in Scotland are therefore the same as those in England and Wales, subject to subtle differences stemming from a different legal system in Scotland. The Scottish Government has devolved responsibility for policy and recording information about CVLs and receiverships in the same way as for compulsory liquidations.

In Northern Ireland, administrations, administrative receiverships and CVAs are dealt with under the Insolvency (Northern Ireland) Order 1989, and the Insolvency (Northern Ireland) Order 2005 made similar provisions for administration to those in England and Wales. Data on administrations, administrative receiverships, CVAs and CVLs following administration are only available back to Q4 2009, because the company register for Northern Ireland merged with that for Great Britain in October 2009.

4. Individual insolvency in England and Wales

This section relates to England and Wales only, as there are important differences in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Individual insolvency applies to people, rather than companies, who have had problems with debt and have entered a formal insolvency procedure. There are other ways for individuals to deal with their debts, such as debt management plans or other informal agreements, but no official statistics are currently collected regarding these.

The Insolvency Statistics cover three formal insolvency procedures: bankruptcies and debt relief orders (both of which involve the individual being discharged from their debts, usually 12 months after the start of insolvency), and individual voluntary arrangements (which involve binding agreements whereby creditors are paid some or all of what they are owed, usually over a period of 5-6 years). Insolvency Service statistics also include Breathing Spaces, which provide people with temporary protection from enforcement action and contact from creditors.

Data on individual insolvencies in England and Wales comes from ISCIS, the Insolvency Service’s electronic case management system. Information on breathing spaces comes from the Breathing Space register, which is an IT system owned by the Insolvency Service.

4.1 Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a form of debt relief available to anyone who is unable to pay their debts. A bankruptcy order is made either:

- by the Adjudicator, for people applying for their own bankruptcy

- by the court, for those petitioning to make someone else bankrupt

For petitions presented before 6 April 2016, all bankruptcy orders were made by the court.

Once a bankruptcy order is made, a trustee manages the bankruptcy – either the official receiver (an officer of the court) or a licensed insolvency practitioner (IP). Assets (with some exceptions) owned by the bankrupt at the date of the bankruptcy order are sold by the trustee, who distributes the proceeds to creditors after the fees and costs of the bankruptcy are deducted. Individuals are discharged (released) from debts and bankruptcy restrictions usually 12 months after the bankruptcy order is made.

A simplified summary of the bankruptcy process is in Figure 2 below:

Source: Insolvency Service

Key data recorded by the Insolvency Service about bankruptcy

The event of bankruptcy

For creditor petitions, the Insolvency Service receives information from the court when the bankruptcy petition is first presented, and when the court order is made. For debtor applications, the Insolvency Service receives information when the application is made. It is a legal requirement for the Insolvency Service to be notified of all bankruptcies in England and Wales, so numbers of bankruptcies recorded in the Insolvency Statistics should be complete. The date of the bankruptcy order is used in compiling the statistics, as opposed to the date the information is received from the court or Adjudicator or entered onto ISCIS. On occasion, information is received from the court after the cut-off period for extracting data for the monthly publication. Numbers for previous periods are revised in the statistics when late information is captured.

Personal information about the bankrupt

The electronic bankruptcy application (EBA) or preliminary information questionnaire (PIQ) includes information on: the bankrupt’s name, address, date of birth, gender, national insurance number, marital status, employment status, number and ages of all in the bankrupt’s household (including dependents). The information in the EBA/PIQ is generally assumed to be true, but if the bankrupt is interviewed the examiner has the opportunity to verify this information.

Information about address, gender and date of birth are used for Official Statistics, but are not fully complete. This can be because the bankrupt fails to complete their EBA/PIQ and/or attend interview, or the information is not recorded on ISCIS for other reasons. In 2023, 0.8% of bankrupts had unknown address data; 2.2% had unknown date of birth, and 3.5% had unknown gender. Other personal information is not currently used for Official Statistics, but is likely to have similar issues with completeness.

Employment status and industry

The EBA/PIQ records whether the bankrupt is employed, self-employed or unemployed. This information is recorded differently on ISCIS in an ‘occupation’ field, specifying whether the bankrupt is a company director, housewife/husband, retired, student and so on. This information is not currently used for Official Statistics, and the information is not stored in the data warehousing facility from which data for the official statistics are extracted.

The examiner records separately whether the bankrupt is self-employed, and selects an industry code based on the 2003 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codings. While the harmonised standard for industry classifications is currently the 2007 SIC, the Insolvency Service’s administrative systems do not currently support this standard. This information is entered on a separate part of ISCIS, and there is no validation rule which compares this information with the ‘occupation’ field above. This information is used in the Insolvency Statistics, but is not complete: in some cases, trading status is recorded as ‘non-surrender’ (the bankrupt does not provide the information) or ‘unknown’. In 2023, where bankrupts were identified as being self-employed, 0.2% of self-employed bankrupts had their industry classified as ‘unknown’, so these data are almost complete; however the quality of the data relies on information being correctly entered into ISCIS.

Changes to the industry classification used on ISCIS were made between Q3 and Q4 of 2006. As a result of this change, industry breakdowns published in the current statistical tables are not consistent with previously published editions that cover 2006 and earlier.

Cause of insolvency

The EBA/PIQ asks for the reason why the individual became bankrupt, in the bankrupt’s own words. Based on this information and/or the interview (if held), the examiner records the cause of insolvency, using a coding frame (for example, ‘living beyond means’, ‘failure to deal with tax affairs’, ‘loss of employment’, ‘loss/significant reduction in household income’). This information is not currently considered suitable for use in Official Statistics. Sometimes, the individual does not cooperate with the bankruptcy process, and so the cause of insolvency is recorded as “non-surrender”; in 2023, about 3% of cases were recorded in this way. A further 20% of individuals had an “unknown” cause of insolvency recorded.

Assets

Most assets (the bankruptcy estate) vest in (become the responsibility of) the trustee so that they can be realised (sold). The bankrupt is required to disclose all assets. Some assets, such as household items and clothing, or tools of the bankrupt’s trade, are treated as exempt from the bankruptcy estate. The bankrupt makes an estimate of the value of each of their assets, which is recorded on ISCIS. Separately, the examiner records estimates of the realisable value (likely sale price) of each asset. Both of these estimates are subjective, and are often recorded to the nearest round number, or as zero.

When assets are sold, the realised amount (actual sale price) is recorded. In most cases, there are little or no assets in the bankruptcy estate, but for those cases with substantial assets (such as property) it can take a long time – sometimes several years – to complete the sale of assets. And where an IP (rather than the official receiver) is the trustee in bankruptcy, information on realised amounts is not recorded against individual assets on ISCIS.

The value of assets in bankruptcy is not currently considered suitable for use in Official Statistics.

Debts and creditors

The bankrupt lists their known creditors and the estimated amount owed to each in the EBA/PIQ. If an interview takes place, this is discussed with the examiner. The official receiver sends a report to creditors which lists the debts owed, often grouped by type of debt (for example ‘credit cards’, ‘debts to family’ and so on). Creditors are asked if they wish to make a claim on the bankruptcy estate (wish to share in the money recovered from selling assets). To do this, creditors send a proof of debt to the trustee. The amount of debt claimed is recorded for each creditor, which may be different from the amount estimated by the bankrupt (who may, for example, have not included any interest payments). However, in most bankruptcies, there is no distribution to creditors because there are little or no assets in the bankruptcy estate. It is common, therefore, for creditors not to make a claim and for this information to be left blank.

The value of debts in bankruptcy is not currently considered suitable for use in Official Statistics.

Income payments

Bankrupts who can make reasonable contributions to their debts are required to do so under an income payments agreement (IPA). If they do not agree, the official receiver or trustee in the bankruptcy will apply to court for an income payments order (IPO). IPA or IPO payments come from surplus income – money left over from income after reasonable living expenses have been deducted. An IPA or IPO will normally be payable for 36 months, but can sometimes be agreed for one-off payments. The number of bankruptcies which result in an IPA or IPO is currently included in the Insolvency Statistics, and should be complete. The cash value of IPAs and IPOs is not currently included.

Legislative changes affecting bankruptcies

Bankruptcy is mostly dealt with under the Insolvency Act 1986, which replaced the Bankruptcy Act 1914. A quarterly time series of bankruptcies in England and Wales is available from 1960. Income payment orders were introduced under the 1986 Act.

The Enterprise Act 2002 reduced the bankruptcy discharge period from three years to one, and introduced early discharge (since repealed) for eligible cases. It also introduced Bankruptcy Restriction Orders (BROs) and Bankruptcy Restriction Undertakings (BRUs), which impose certain restrictions on bankrupts for between 2 and 15 years, if they have been reckless or dishonest. Income payment agreements were also introduced under this Act.

The Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 introduced a new route into individual insolvency called the debt relief order (DRO), which came into effect from 6 April 2009. It is likely that some individuals with a DRO would have become bankrupt if DROs had not been introduced, thereby reducing the number of bankruptcies. On 1 October 2015 and 29 June 2021, the Insolvency Proceedings (Monetary Limits) (Amendment) Order 2015 (and the equivalent for 2021) increased the debt, asset and income levels in the eligibility criteria for debt relief orders, making more people eligible for DROs. This was expected to decrease the number of bankruptcies.

The Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 changed the process by which an individual may apply for their own bankruptcy, by using an administrative rather than court process, and using electronic application. Since April 2016, the office of the Adjudicator determines whether or not to make a bankruptcy order on the basis of the application. This Act also repealed early discharge for bankrupts.

On 1 October 2015 the Insolvency Act 1986 (Amendment) Order 2015 introduced changes to the creditor petition limit for bankruptcies. Since this time, creditors (or groups of creditors acting together) must be owed a minimum of £5,000 to petition for bankruptcy, compared to the previous limit of £750.

4.2 Debt Relief Orders (DROs)

Debt relief orders are a form of debt relief currently available to those who have qualifying debts totalling up to £30,000, assets of under £2,000 (excluding a vehicle worth no more than £2,000 and certain personal belongings and household items), and less than £75 in surplus income per month. These limits will be changed to £50,000 debt and £4,000 for a vehicle on 28 June 2024.

A DRO provides 12 months protection from creditor action (the “moratorium period”) unless a creditor gets leave of the court. After this period, the debts are discharged. However, in contrast to bankruptcy, it is only the scheduled qualifying debts that are discharged at the end of the moratorium period. Some debts are excluded from a DRO (such as student loans, child support and maintenance, and criminal fines) and individuals are still liable to pay these after discharge.

DROs are an administrative rather than a court procedure. Individuals enter the web-based DRO application system through an approved intermediary (a trained debt advisor). The intermediary discusses the individual’s financial position, and completes the DRO application on behalf of the individual before submitting it to the Insolvency Service’s DRO team. The official receiver decides whether or not to grant the DRO. A simplified summary of the DRO process is summarised in Figure 3 below. Note that on 6 April 2024, the £90 application fee was abolished.

Source: Insolvency Service

Key data recorded by the Insolvency Service about DROs

The event of the DRO: the outcome of all DRO applications is decided by the official receiver in charge of the Insolvency Service’s DRO Team. The decision whether to grant the DRO, and the date of the DRO, is recorded on ISCIS immediately. The number of DROs recorded in the Insolvency Statistics is a complete record of all DROs in England and Wales.

Personal information about the individual: the approved intermediary records a range of personal information when completing the DRO application.

Information on date of birth, gender, and address is used for Official Statistics. Data on date of birth were complete in 2023, but gender was missing in 1.5% of cases. For 0.5% of individuals granted a DRO in 2023, the postcode recorded could not be matched to the National Statistics Postcode Lookup.

Information on disability, ethnicity, national identity, marital/same sex civil partnership status, number of dependent children and NI number is not currently used for Official Statistics. Harmonised standards are used for ethnicity, national identity and marital/same sex civil partnership status. Harmonised standards are not used to collect information on disability; instead individuals are asked whether they are registered disabled, and one of a number of categories of impairment is recorded.

Employment status: this is not currently used for Official Statistics. Harmonised standards are not used to collect this information; instead individuals are asked whether they are employed, unemployed, self employed, retired, housewife/husband (inc. caring for dependents) and so on.

Assets: this information is collected to assess eligibility for a DRO, but is not currently used for Official Statistics. The approved intermediary records data on any cash or other assets the individual has, including details of any car.

Debts and creditors: this information is collected to assess eligibility for a DRO, but is not currently used for Official Statistics. The approved intermediary records data on debts owed to each creditor. This is verified by the Insolvency Service through checking against an external credit reference agency’s records (though each credit reference agency’s records for a given individual may not be complete); and by writing to all creditors whose debts are included in the DRO (detailing how they may object to the approval of the DRO).

Income and expenditure: this information is collected to assess eligibility for a DRO, but is not currently used for Official Statistics. In the majority of cases the approved intermediary completes the Common Financial Statement, a form which records detailed information on all income and expenditure. ‘Trigger figures’ are used for certain elements of expenditure (such as housekeeping) to check that expenditure is reasonable given the size and composition of the individual’s household. At the end of the form, the amount of surplus income is calculated.

Legislative changes and other factors affecting DROs

The Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 introduced DROs, which came into effect from 6 April 2009. In April 2011 the legislation was changed to allow those who have built up value in a pension scheme to apply for debt relief under these provisions.

The Insolvency Proceedings (Monetary Limits) (Amendment) Order 2015, and the equivalent order in 2021, introduced changes to the eligibility criteria for debt relief orders, effective 1 October 2015 and then 29th June 2021. The upper limit for scheduled qualifying debts increased from £15,000 to £20,000 in 2015 and then to £30,000 in 2021, and the upper limit for assets (excluding a motor vehicle) increased from £300 to £1,000 in 2015, and to £2,000 in 2021. On 28 June 2024, these limits will be changed to £50,000 debt and £4,000 for a vehicle. Additionally, in 2021 the surplus income limit increased from £50 per month to £75 per month and the value of a motor vehicle that can be disregarded from the assets increased from £1,000 to £2,000. These changes resulted in increases to the number of DROs and may have lowered the number of bankruptcies.

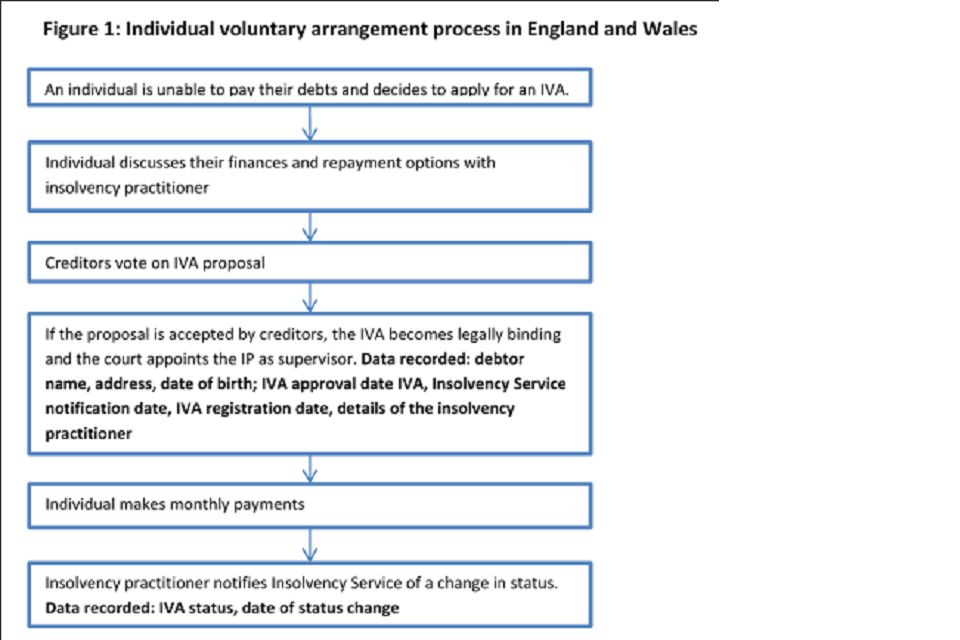

4.3 Individual voluntary arrangements (IVAs)

Individual voluntary arrangements are a means of repaying creditors some or all of what they are owed over a period of time. IVAs are set up by licensed insolvency practitioners, who discuss the individual’s income, expenditure, debts and assets; and make a proposal to the individual’s creditors. If 75% (by value of debts) or more of creditors approve the proposal, the agreement is binding on all. The court is notified of the creditors’ decision and the IVA is supervised by the insolvency practitioner.

Insolvency practitioners are required to notify the Insolvency Service of all new IVAs that have been approved under their supervision, and of certain events as they occur. Insolvency Service Official statistics report IVA numbers based on the date at which they were registered with the Insolvency Service. This is typically 1-2 weeks later than the IVA is approved, although in some cases the registration of IVAs is delayed by a month or more.

A simplified summary of the IVA process is shown in Figure 4 below.

Source: Insolvency Service

Key data recorded by the Insolvency Service about Individual Voluntary Arrangements (IVAs)

The event of the IVA: the Insolvency Service receives information from insolvency practitioners when an IVA has been approved. It is a legal requirement for the Insolvency Service to be notified of all IVAs in England and Wales, so numbers recorded in the Insolvency Statistics should be complete. The date that the IVA was registered is used in compiling the statistics, as opposed to the date the IVA was approved. This is because there can often be a delay of some weeks between approval and registration, so using this method reduces the need for large revisions to the data.

Personal information about the individual: the insolvency practitioner records basic personal information when notifying the Insolvency Service. Information on date of birth, gender, and address is currently used for Official Statistics. In 2023, data on date of birth were complete and gender was only missing in three cases. Address details were either missing or did not match the National Statistics Postcode Lookup in less than 0.1% of cases.

Change of the status of the IVA: the insolvency practitioner notifies the Insolvency Service if the status of the IVA changes, and the date of the change. This information is used for the IVA Outcomes and Providers Official Statistics.

The status can be one of the following:

- current: where the arrangement is continuing;

- completed: where the supervisor has issued a certificate (“the completion certificate”) stating that the debtor has complied with their obligations under the arrangement;

- terminated (failed): where the supervisor has issued a certificate (“Certificate of Termination”) ending the arrangement because of the debtor’s failure to keep to the terms of the arrangement;

- revoked / suspended: where an application has been made to challenge the decision of a meeting approving an IVA, the court may revoke or suspend the approval or call for further meetings to be held. Notification of such action should be forwarded to the Secretary of State within 7 days of the making of the order.

Details of the IVA: other than some limited personal information about the individual and certain key dates about the IVA, insolvency practitioners are not required to provide data. This means the Insolvency Service does not hold information about, for example:

- the amount of debt (total, or amount owed to each creditor);

- the expected length of the IVA;

- the value of monthly repayments;

- the insolvency practitioner’s fees;

- the outcome of annual reviews; and

- whether the IVA was compliant with the IVA Protocol (see below)

Legislative changes and other factors affecting IVAs

IVAs are dealt with under the Insolvency Act 1986, and a time series is available back to 1987. IVAs were originally intended as a means for self-employed individuals to deal with their debts while still being able to run their business, but over time insolvency practitioners have marketed IVAs to consumers as a way to deal with (for example) credit card debt.

There was a rapid increase in the number of IVAs between 2004 and 2006, which coincided with high levels of advertising by IVA providers. In response to concerns raised, the Insolvency Service led the development of a voluntary agreement aimed at encouraging best practice and streamlining the process for straightforward consumer IVAs. This IVA Protocol has been in effect since February 2008.

Numbers of IVAs increased again between 2015 and 2019 and reached a record high annual number in 2022. However, numbers decreased during 2023, which coincided with changes to the wider regulatory landscape. These included the FCA introducing a ban on debt-packagers receiving remuneration for referrals to IVA firms; and Recognised Professional Bodies adopting a new Statement of Insolvency Practice in relation to take-on procedures.

IVAs have effectively replaced Deeds of Arrangement, which are still available but are very rarely used: the last recorded deed was registered in Q2 2004. Deeds of Arrangement are another statutory insolvency procedure involving an agreement with creditors. Only those creditors who vote in favour of the deed are bound by its terms; dissenting creditors can still pursue other enforcement actions to recover their debts.

4.4 Breathing spaces in England and Wales

Insolvency Service statistics also include Breathing Spaces, which provide people with temporary protection from enforcement action and contact from creditors. A breathing space is not a formal insolvency procedure, although some people will enter a formal insolvency procedure after their breathing space ends. Breathing spaces were created by the Debt Respite Scheme (Breathing Space Moratorium and Mental Health Crisis Moratorium) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020, which came into force on 4 May 2021.

There are two types of breathing spaces. A standard breathing space gives a person with problem debt legal protection from creditor action for up to 60 days. During this time, most enforcement action is paused, most contact from creditors is prohibited, and most charges and interest on the debts are frozen. A person can only have one standard breathing space per year. A mental health crisis breathing space is only available to people who are receiving mental health crisis treatment. Mental health breathing spaces have stronger protections and last as long as the person’s mental health crisis treatment, plus 30 days.

The Insolvency Service holds information on the number of breathing spaces, as well as the location and age of people with breathing spaces. This information is provided in official and ad-hoc statistics. It also holds management information on breathing spaces, such as the duration, the number managed by each debt advice group, and reasons for cancellations.

5. Individual insolvency in Scotland and Northern Ireland

Legislation and policy on individual insolvency in Scotland and Northern Ireland is different to that for England and Wales. In Northern Ireland, individual insolvency is broadly comparable to England and Wales, but changes in legislation and policy occurred on different dates. In Scotland, while the policy aims are similar, the individual insolvency framework operates differently and so numbers are not comparable to England and Wales, or to Northern Ireland (particularly if broken down by the type of insolvency).

5.1 Individual insolvency in Scotland

Insolvent individuals in Scotland are dealt with under the Bankruptcy (Scotland) Act 1985, as amended by the Bankruptcy (Scotland) Act 1993 and the Bankruptcy and Diligence etc. (Scotland) Act 2007. There are two types of individual insolvency in Scotland:

- bankruptcy, also known as sequestration, which is similar to bankruptcy in England and Wales

- protected trust deeds (PTDs), which are voluntary arrangements fulfilling a similar role to IVAs in England and Wales.

These forms of insolvency are set up and administered differently to their analogues in England and Wales – there are different entry criteria, fees and lengths of repayment. Further information about individual insolvency in Scotland can be found on the Accountant in Bankruptcy website.

Legislative changes affecting individual insolvency in Scotland

In April 2008, a new route into bankruptcy was created for individuals with low income and low assets (LILA). The numbers of bankruptcies increased immediately as a result of this change, so comparison of data after Q2 2008 with that before should bear this change in mind.

In November 2013, the Protected Trust Deeds (Scotland) Regulations 2013 introduced a number of changes to PTDs, including a requirement to pay 48 monthly contributions, rather than 36. Prior to these regulations, both bankruptcies and PTDs involved a 36 month contribution period. This meant that between 28 November 2013 (when these regulations came into force) and 1 April 2015, a debtor may have chosen bankruptcy over a PTD as this would have resulted in having to pay fewer contributions. This may have been a factor in the decline in the number of PTDs in 2014.

The Bankruptcy and Debt Advice (Scotland) Act 2014 introduced a new ‘Minimal Asset Procedure’ (MAP) route into sequestration, replacing the previous LILA route from 1 April 2015. MAP is only available to individuals who meet certain criteria, for example, that they have been receiving income-related benefits for at least 6 months or have been assessed, using the Common Financial Tool, as being unable to pay a contribution towards their bankruptcy. The individual’s debt must be between £1,500 and £17,000 to qualify for MAP.

The 2014 Act also changed the contribution period for sequestration, increasing it from 36 months to 48 months, bringing it into line with the change introduced in 2013 for PTDs. The Scottish Government has promoted the use of debt payment programmes under the Debt Arrangement Scheme. These are not formal insolvencies, but are binding agreements with creditors to repay debts in full over an agreed period.

5.2 Individual insolvency in Northern Ireland

Individual insolvency in Northern Ireland operates in much the same way as in England and Wales, but under different legislation:

- The Insolvency (Northern Ireland) Order 1989

- The Insolvency (Northern Ireland) Order 2005 (which implemented similar changes to bankruptcy procedures as the Enterprise Act 2002 introduced in England and Wales)

- The Debt Relief Act (Northern Ireland) 2010, which introduced DROs in Northern Ireland from 30 June 2011. The eligibility limits were increased in 2016 in line with the changes in England & Wales made in 2015. However as of September 2022, the eligibility criteria differed from England & Wales, because the debt, income and asset thresholds were increased in England & Wales in 2021, but not in Northern Ireland.

Further Information about individual insolvency in Northern Ireland can be found at the Department for the Economy website.