Lease-based providers of specialised supported housing

Published 4 April 2019

Applies to England

Addendum to the Sector Risk Profile 2018 - April 2019

Contents

-

Introduction

-

Executive summary

-

What is specialised supported housing?

-

What is the lease-based model for specialised supported housing?

-

Specific concerns of the RSH with regards to meeting Regulatory Standards

-

Annex 1: What can the market expect from the RSH?

1. Introduction

1.1 This note is an addition to the Sector Risk Profile published in October 2018 and supplements the section in that publication on lease structures. It is aimed at anyone with an interest in the recent expansion of the specialised supported housing sub-sector regulated by the Regulator of Social Housing.

1.2 Since the near failure of First Priority Housing Association in early 2018, the RSH has been engaging with providers of this type of accommodation whose business model is predicated on taking long-term leases from property funds, to establish whether the issues at First Priority are replicated elsewhere. As a result of this work, the RSH has published a number of regulatory judgements and notices where it has identified concerns about the governance or financial viability of these providers.

1.3 The series of judgements published by the RSH has raised concerns about its view of the long-term sustainability of the lease-based model. This note is intended to explain its views and ensure that anyone with an interest in this sub-sector understands what they can expect of the RSH in the future.

2. Executive summary

2.1 Following the near failure of First Priority Housing Association in 2018, the RSH has been engaging with a range of registered providers (RPs) of specialised supported housing and has downgraded a number of the organisations to a non-compliant grading for governance and/or financial viability.

2.2 These regulatory judgements and notices have revealed some recurring themes, which include:

-

the concentration risk that comes from having long-term, low-margin inflation-linked leases as a single source of finance;

-

the thin capitalisation of some of the RPs undertaking this model;

-

poor risk management and contingency planning undertaken by some of the RPs;

-

some inappropriate governance practises that have led to poor decision making;

-

a lack of assurance about whether appropriate rents are being charged.

2.3 The five factors above have at times led to poor service delivery and failure to meet health and safety and other statutory requirements. Weak governance at many of these organisations has led them to develop business models that are unsustainable in the longer term and cannot withstand foreseeable downside risk.

2.4 The social housing sector has so far enjoyed strong credit performance, which has sometimes led to a perception that having an RP as a counterparty will mean minimal credit risk. However, the RSH does not guarantee the performance of financial obligations of RPs in general or the viability of any individual RP in particular.

2.5 If an RP is in financial difficulty and tenants are at risk, the regulator can use a range of intervention powers to protect the interests of those tenants and maintain the social housing assets in the regulated sector. The regulator may also facilitate discussions between a failing RP and a financially stronger RP who may be able to help. Nevertheless, any decision to offer or receive financial support is a matter for the boards of the respective RPs.

2.6 Private investment plays an important role in supporting much needed growth and sustainable development of the SSH sector and positively impact lives of very vulnerable people in our society. However, there is also the potential that some of the providers currently delivering SSH are taking on risks without the resources and skills needed to manage those risks. This could ultimately undermine their ability to continue to offer this provision.

3. What is specialised supported housing?

3.1 Social housing helps those whose needs are not served by the commercial housing market and is offered at below-market rents. The majority of social housing is termed general needs and can be occupied by anyone who meets the allocation criteria of the local authority (LA) or housing association. However, many social housing providers also offer supported housing. As the name suggests, supported housing is provided together with support to help people live independently. It plays a key role in enabling some of the most vulnerable people in our society to live independently.

3.2 SSH is a specific type of supported housing defined in the Housing Rents (Exceptions and Miscellaneous Provisions Regulations 2016) [^3] as specifically designed or adapted for people who require specialised services to enable them to live independently as an alternative to a care home, and where the level of ongoing support provided is approximately the same as that provided by a care home. It must be provided by a private registered provider under an agreement with an LA or the NHS, and not receive any public assistance (also defined in the regulations) for its construction or acquisition.

3.3 There is growing demand for this type of accommodation from LAs who need to meet their statutory obligations to house vulnerable adults.

4. What is the lease-based model for specialised supported housing?

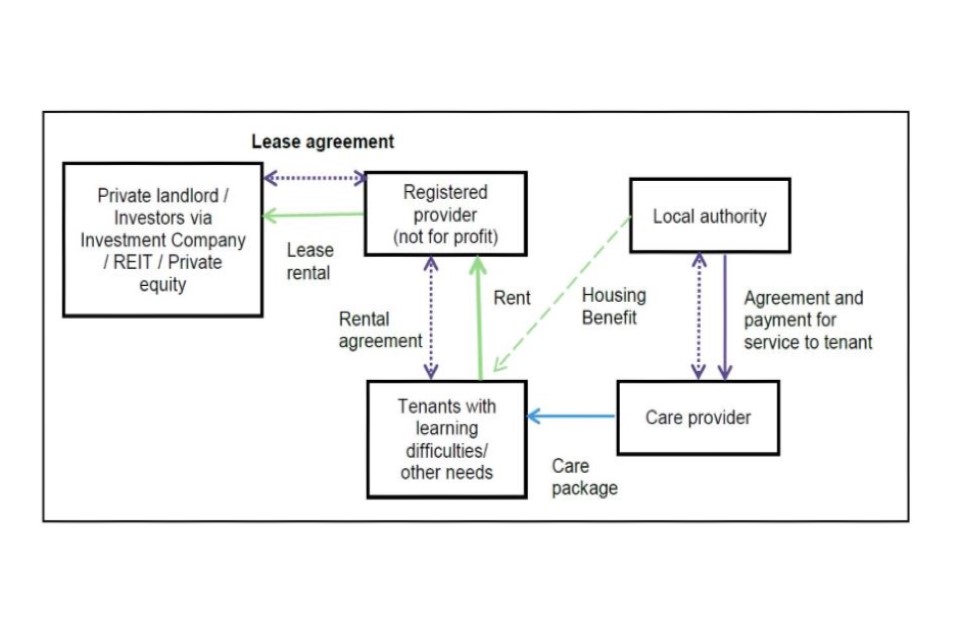

4.1 Over the last few years a new funding model has developed that uses a lease structure to allow a rapid expansion of SSH provision. This model has seen a number of property funds, private equity investors and individuals provide accommodation on long-term leases (typically 20 years and more) to an RP who lets the home to an individual via nomination arrangements with an LA, which also commissions a care package for the tenant alongside the home. Generally this commissioning of the care and the home happens on a three to five-year cycle. We refer to this as the lease-based model of operation.

4.2 Providers using the lease-based model are typically small; although the capital-light nature of the model has allowed some of these organisations to grow very quickly; some of them now have over 1,000 bed spaces.

4.3 The rent for the units is set by the RP and is a charge for the right to occupy the property. In addition, charges for specific property-related services (e.g. maintenance of communal areas, security) can be levied, if provided for in the occupation agreement, and should reflect the actual cost of the services provided. Separately, there will be a care package arranged with a care provider (normally a different organisation to the RP) that provides the support needed by the individual to meet their needs.

4.4 As shown in Figure 1, tenants are responsible for paying the rent and service charges to their landlord RP and are often eligible to receive Housing Benefit to cover the cost of their housing. The LA administers the Housing Benefit payments on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions and will review claims made to ensure that they are not unreasonably high. This means that Housing Benefit is often assumed to underwrite the rental stream and reduce the risk of non-payment. In addition, the LA will normally meet the costs of the care package for the individual, but this transaction is between the LA, the individual and the care provider and does not normally affect the RP.

Figure 1: Specialised supported housing – lease-based model

Specialised supported housing – lease-based model

4.5 Within this structure, leases are typically on full repairing and insuring terms with periodic uplift (normally annually) in lease payments linked to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or sometimes the Retail Price Index (RPI). The RP funds the lease payments from the rental inflows and the business should be run so that there is sufficient cash left after the lease payments to manage and maintain the properties and cover the RP’s overheads.

5. Specific concerns of the RSH with regards to meeting Regulatory Standards

5.1 The review of a range of lease-based providers carried out by the RSH has raised some concerns about the way the model is being used by a number of those providers to fund the provision of SSH. These concerns fall into the following five broad categories.

The risk that comes from only having long-term, low-margin, inflation-linked leases as a source of finance

5.2 The use of a single source of finance for a business is not inherently an issue, but often brings with it particular risks that would not arise if a broader range of financing sources were used. A lack of diversification can exacerbate the risk inherent in the chosen source of finance. Having one bond for example can create a significant refinancing risk that would not arise if a range of debt instruments and maturities were used. Similarly having only long-term, inflation-linked leases increases the exposure of organisations to inflation. A business model that assumes income will be covered by Housing Benefit is exposed to future changes in welfare policy, and a model with tight margins has limited capacity to manage shortfalls in income or increased costs.

5.3 In the SSH sector, lease terms are normally on a full repairing and insuring basis for 20 years and more (though we have also seen examples of 50 years) and in most cases there are no break clauses. Agreements from the LAs to cover the costs of the rent with Housing Benefit are linked to a specific tenant, while nominations agreements with care operators to supply tenants are for between six months and five years. This means that there will be potential points where a break in rental income may occur due to the care operator failing to renew its agreement, a lack of suitable tenants, or Housing Benefit coverage not being agreed. This exposes the RP to a potentially significant void or rental shortfall risk.

5.4 Cash outflows via lease rental payments are generally linked to changes in CPI plus an agreed premium (say CPI+1 %). Cash inflows via rental income for the RP are linked to three variables: the rent charged; the occupancy rate; and the number of units that are available and in a fit condition to let.

5.5 As the Housing Benefit awards and nomination agreement terms are for much shorter periods than the lease term, it is imperative that the properties remain tenanted and the void period between lettings is kept to a minimum. The process needs to be carefully managed with the local authority, care provider and the new tenant, bearing in mind that tenant’s specific needs.

5.6 Finally, only well-maintained properties that meet all the appropriate health and safety standards and those fit for purpose with the necessary adaptations to suit a specific tenant’s needs can be occupied. The RP needs to ensure that this is the case, both at the outset and throughout the lease period. We have identified cases where the tight margin between rental income and lease commitment has led to reduced expenditure on maintenance and statutory health and safety compliance. This can never be acceptable.

5.7 Although the demand for SSH is high, the financial performance of a lease-based RP depends on being able to consistently ensure high levels of occupancy across its specific, specialised portfolio for the duration of the leases. High void rates negatively impact cash inflows. We are aware, in some instances, of void losses as high as 40% due to a combination of unlettable property requiring works (and that do not meet statutory health and safety requirements) short-term voids and long-term under-occupancy.

The thin capitalisation of some of the RPs undertaking this model

5.8 Rapid expansion of any business can lead to risks of overtrading and inadequate working capital. Significant stress on cash flows can lead very quickly to a deteriorating financial position. Although premiums or fees paid at the start of a new lease arrangement can help an RP fund working capital they are not a substitute for effective cash management. Indeed, the payments of the premiums can sometimes incentivise RPs to take on new business and therefore potentially detract from running their existing business effectively.

5.9 Most of the organisations that are undertaking this model have very little balance sheet capacity, cash or other assets that they can call upon if there are any interruptions to their rental cash flows. This can leave their business plans vulnerable to rapid deterioration if any of the core assumptions made by these providers turns out to be erroneous. This is quite a different business model to more established RPs, who will typically be better capitalised, operate with higher margins and have a range of assets and income streams with which to manage any issues in one area of their business.

A lack of assurance about whether appropriate rents are being charged

5.10 There are at least two issues that can affect the rental income for the RP. First there is a risk that changes in Government policy could change the availability of Housing Benefit for SSH tenants. Second, the LA would generally treat the claim made by the tenant as an ‘exempt accommodation’ claim and determine whether the rent can be covered by Housing Benefit. For the claim to be treated in this way, the LA requires the landlord to be a not-for-profit entity, with care and support being provided at the property (though not usually by the landlord). The not-for-profit status of the RP is therefore important if the RP is dependent on a high proportion of the rent being covered by Housing Benefit. For any part of the rent not covered, the RP is exposed to the risk of non-payment by the tenant (or the credit risk of the tenant). All of the providers we have engaged with were reliant on 100% rental coverage from Housing Benefit.

5.11 For properties that the RP reports as part of their SSH provision, the RP boards need to assure themselves that:

-

the rents charged are in fact below-market rents (which is part of the definition of social housing in the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008), and

-

that the letting meets the definition of SSH in the Social Housing Rents (Exceptions and Miscellaneous Provisions) Regulations 2016, as explained in the above section: What is specialised supported housing?.

5.13 In cases where an RP is unable to demonstrate that the homes they let are social housing as defined in the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008, it may be appropriate for the RSH to review the registration of the RP as a social housing provider. On the other hand lowering the rent to below market levels may make the contractual lease payments unaffordable and increase the stress on cash flows.

Poor risk management and contingency planning undertaken by some of the RPs

5.14 Given the thin capitalisation of many of these providers, ensuring continuity of rental income is vital and an ability to manage the risks associated with collecting the appropriate rents is a key governance challenge.

5.15 If for any reason the RP is unable to collect its rents, for example due to void properties, then the RSH will want to know how the board will manage the financial and operational risks that flow from the reduced levels of income. In particular, it will want to ensure that the tenants are not put at any risk and that their services continue to be delivered effectively. Where providers are unable to give those assurances to the RSH then they can expect regulatory action to follow, which will escalate until the provider is able to resolve the issue.

5.16 It is a regulatory expectation that boards of all RPs have a thorough understanding of the risks to the social housing assets, and that they effectively stress test their business plans and have appropriate mitigation strategies in place. When engaging with a number of the SSH providers (as shown through our published regulatory judgements) the RSH has found limited evidence of convincing mitigation plans which could be implemented without relying on third parties, or business models that can withstand foreseeable risks arising from the issues surrounding their lease terms, void risks and exposure to future commissioning cycles or welfare policy.

5.17 As these are RPs that are growing quickly and housing vulnerable people, it is not acceptable for the boards to fail to think through and plan to mitigate these risks. The start-up nature of many providers of SSH does not excuse them from this basic regulatory requirement. One of the key questions for the boards and the RSH is how these risks can be mitigated within the constraints of the current funding model of long-term leases with no break clauses and a CPI link as the only source of finance.

Some inappropriate governance practises that have led to poor decision making

5.18 Good governance is critical for the proper working of any organisation. The regulator expects RP boards to be properly resourced and appropriately skilled to be able to take decisions needed and be fully aware of the risks borne by the business. We have identified cases where boards have paid minimal attention to lease terms and documentation, and consequently have taken on obligations which will be difficult or impossible to meet. In other cases, boards have taken on properties across a wide geographical area, without a coherent approach to managing and maintaining them.

5.20 In the process of the regulatory work we have been undertaking, the regulator has also observed a network of relationships between the various stakeholders that raise questions about the intention and ability of the board of the RP to act independently in the RP’s own interest. For example, board members, shareholders or executives of the RP may also have roles with a developer or aggregator, which may in turn supply property to investors or provide management and care services through related parties or organisations. While conflicts such as these are capable (in principle) of being managed, they can also result in the lack of effective challenge during board discussions when people need to formally step aside to manage a perceived or real conflict of interest. They may also give rise to the potential for probity issues and reputational damage.

5.21 Poor quality governance does not only manifest itself in conflicts of interest, but can also be seen in poor risk management and operational failure. For example, we have seen evidence of boards not sufficiently focussed on ensuring that their homes meet all of the necessary health and safety standards or have been unsure of the types of support needs of their tenants. The speed of growth of some of the SSH providers has meant that in some cases the levels of skills and oversight needed at board level has been missing and this has led to poor outcomes for tenants and the organisations. Where this has happened the regulator has reflected this in its regulatory judgements and notices and is engaging proactively with the boards to try and remedy the situation.

The overall impact of the five common issues

5.22 As a result of the issues discussed above the RSH is concerned that there is a concentration of risk within the SSH sub-sector that needs to be addressed. These issues can lead to poor quality service to tenants, failure to maintain properties to required standards, and organisations that cannot manage their risks effectively.

5.23 The RSH is concerned that weak governance at many of these organisations has led to them to develop business models that are unsustainable in the longer term and cannot withstand foreseeable downside risk. It is currently hard to see how a provider of SSH which is substantially financed by long-term leases and subsequent tight margins can meet the requirements of the Governance and Financial Viability Standard.

5.24 The RSH intends to work with the boards of the RPs, many of which have been strengthened in recent months, to establish whether they can develop a long-term business model that meets regulatory standards, and address the five issues set out in this note. This could involve, for example, introducing capital or amending terms to increase margins and reduce the risks to long-term sustainability.

5.25 However, if the RSH does not believe that it is possible to return an organisation to compliance then it will look to protect the interests of the tenants and seek to achieve the best outcome for tenants. In these circumstances it cannot guarantee that the interest of all stakeholders would be protected, or that creditors and investors would not suffer losses.

Annex 1: What can the market expect from the RSH?

For anyone not familiar with the work of the RSH, this section gives an indication of the types of tools it can use.

Regulatory judgements, notices and grading under review

Regulatory judgements represent the regulator’s view of an RP’s compliance with the governance and the viability requirements in the Governance and Financial Viability Standard. Regulatory notices are issued in response to an event of regulatory importance (for example, a finding of a breach of a consumer standard that has or may cause serious harm) that it needs to make public. Although regulatory judgements are not published for RPs with less than 1,000 units, the RSH may publish a regulatory notice if there is evidence that such a provider is in breach of an economic standard, or it finds serious detriment as a result of a breach of a consumer standard. Where the RSH is investigating a matter and it considers that the investigation might result in a provider (currently judged to be compliant) being re-assessed as non-compliant in relation to the economic standards, the RSH will add it to its ‘Gradings under Review’ list. The purpose of the list is to alert stakeholders to the possibility that the provider may be moving towards non-compliance with a Standard, in line with our obligations to be transparent. Once the investigation concludes, it publishes a new or updated regulatory judgement for the provider and removes it from the ‘Gradings under Review’ list.

Intervention when there are failing governance standards or an RP is in financial difficulties

The sector has a strong track record of performance and where major failures have occurred the RSH has intervened to protect tenants and public money using its regulatory and enforcement powers as appropriate to the presenting issue. However, the RSH does not guarantee the performance of financial obligations of RPs in general or the viability of any individual RP. While past solutions have included stronger providers taking on the obligations of a failed provider this form of rescue cannot be presumed. Effectively managed providers are unlikely to be willing to accept onerous lease commitments or long-term liabilities without receiving an adequate return, both from the leased property and to reflect the risk of acquiring a financially weak or insolvent provider.

Re-designation of profit or not-for-profit status

The regulator is responsible for maintaining the register which must reflect the proper profit or non-profit status of RPs. The RSH must change this designation if it thinks that what was a non-profit making provider has become a profit making provider, and vice versa.

Voluntary or compulsory de-registrations

In certain circumstances the RSH can remove a provider from the register, whether or not the provider applied to de-register. This could include a scenario where there was evidence that the RP did not provide any social housing (as defined in the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008).

OGL © RSH copyright 2019

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us via [email protected]; or call 0300 124 5225 or write to: RSH, Level 2, 7-8 Wellington Place, Leeds, LS1 4AP

RSH regulates registered providers of social housing to promote a viable, efficient and well-governed social housing sector able to deliver homes that meet a range of needs.