Modern Slavery Innovation Fund: phase 1 end term review (accessible version)

Updated 29 December 2021

Summary of findings

The £11 million Modern Slavery Innovation Fund (MSIF) was launched in October 2016 to support innovative projects tackling modern slavery around the world. The fund aimed to tackle the root causes of modern slavery, strengthen efforts to combat slavery and reduce vulnerability, and build an evidence base to better understand what works in the future.

Projects focused on six objectives agreed by the Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery:

-

Reduce Vulnerability to Exploitation

-

Victim Support and Recovery

-

Improve Global Co-ordination

-

Improve Law, Legislation and Policy

-

Encourage responsible business and slavery-free supply chains

-

Improve the Evidence Base

Ten projects were funded in the first round of the MSIF, accounting for £6m, and running from March 2017 – March 2019. The fund supported 7 intervention projects and 3 research projects.

The authors[footnote 1] of this report were contracted as independent experts, via the Stabilisation Unit, to conduct an end term review (ETR) of the ten projects. The review built on the findings of the mid-term review (MTR) conducted in Spring 2018, and specifically aimed to:

-

Assess the extent to which projects achieved their aims and intended impact;

-

Identify lessons for future programming on modern slavery;

-

Assess the extent to which the MSIF has achieved outcomes related to the six objectives set out above.

The Terms of Reference and methodology for the review are included in annexes I and II. Deep dives were conducted by Sasha Jesperson in Ethiopia (Retrak), Ghana (NSPCC), Nigeria (Salvation Army) and South Africa (Strong Together/ Alliance HR), and by Saskia Marsh in India (Freedom Fund and Goodweave), Philippines (Salvation Army) and Vietnam (NSPCC and Pacific Links). In addition, interviews were conducted either in person or by skype with UK based project teams and with St Mary’s University (Saskia Marsh), University of Bedfordshire and IOM (Sasha Jesperson) and UN University (Saskia Marsh). Projects were evaluated on their outcome indicators, and their contribution to the objectives of the MSIF using the CSSF Annual Review Assessment Tool to complement implementers’ own assessments of their results frameworks. Reviewers have provided broad-brush recommendations on individual projects for consideration by the Home Office.

MSIF programme partners had specialist in-house advice and scrutiny on safeguarding vulnerable adults and children throughout Phase 1. A professional technical safeguarding adviser from the Office of the Children’s Champion (OCC) reviewed the quarterly reports of partners with direct service delivery to children and adults and provided advice and recommendations to strengthen protection. As part of the overall safeguarding quality assurance process, five partners’ field activities were assessed midway through Phase 1 to provide further advice to promote the safety and welfare of vulnerable individuals.

Reviewing safeguarding practices was not a key aspect of this review, but relevant points have been noted where identified.

Key findings and lessons learnt

Key findings and lessons learnt from the review are summarised below, alongside key recommendations. Many of these findings reflect best practice and lessons learnt applicable to a variety of programmatic interventions.

1. The MSIF was genuinely an innovation fund, supporting original thinking on modern slavery. Allowing for a more experimental ‘start-up phase’ (as Phase 1 of the MSIF could be considered) has the potential to generate important insights into new methodologies and allow newer entrants to a thematic area an opportunity to demonstrate their ‘value add’ – whether on modern slavery or other issues. As an example of the former, the MSIF has demonstrated the utility of real-time technology to map supply chains vulnerable to modern slavery. On the latter, while some of the grant recipients such as The Salvation Army are not automatically associated with modern slavery programming, they have subsequently demonstrated their ability to provide effective interventions in this space. Other projects include excellent examples of innovation, elements of which could be replicated in other geographies or indeed in closely related thematic issues.

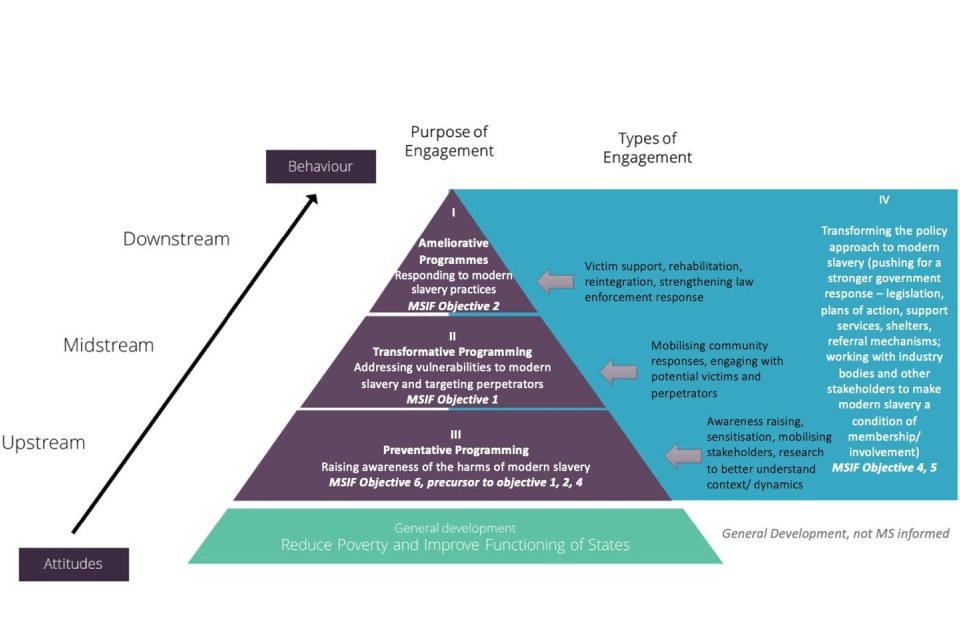

2. Long term, integrated, multi-dimensional approaches are key to tackling complex problems. Most of the programmes funded via MSIF, at their core, are seeking to enact behavioural change. At Annex 3, we introduce a behavioural change framework that explains how some of the projects are already doing exceptionally well at seeking to enact deeper, multifaceted, behavioural change across multiple stakeholders.

3. Evidence from programming on other complex socio-political issues shows that these multi-stakeholder approaches are more likely to be have longer term impact. Modern slavery is just one of the thematic issues high on HMG’s agenda. Increasingly HMG is seeking to target some of its overseas policy and programming on issues which may be transnational in nature, involve multiple drivers and actors, entail complex inter-dependencies between stakeholders, and are underpinned by structural deficiencies (whether political, or socioeconomic). To effectively respond, projects must be embedded in a deep contextual understanding and engage in a variety of activities to institute change. The projects that were the most effective had a clear theory of change and activities that engaged with multiple levers to enact that change. The strongest of these delivered activities across all four categories of the behavioural change pyramid.

4. However, achieving effective and sustainable results when it comes to behavioural change – whether on modern slavery issues, or other thematic areas premised on individual or institutional change in complex environments, takes time: Two years (the lifecycle of Phase 1 funding of the MSIF) is too short a timeframe for most of the projects to generate long term impact. That is not to say that projects under Phase 1 have failed – in fact, several of the implementers should be commended for the impressive results they have achieved so far, while taking a pragmatic, patient approach to generating longer term, deeper, change.

5. Failure to completely achieve some of the desired outcomes and associated indicators is to be expected; given the complexities of addressing modern slavery, and the time it usually takes to achieve sustained behavioural change. However, it is useful for implementers to clearly articulate the overall ‘pathway to change’, even beyond the current funding lifecycle, so that donors can easily understand the desired end state. Conversely, some projects were overly ambitious in what could be achieved in two years. Assessment needs to be made of what is realistic and achievable in the given context, and in line with organisational capabilities, and activities adjusted accordingly.

6. Evidence shows that the most successful behavioural change programmes, whether on modern slavery or other issues, recognise the need to “work politically” in fragile overseas contexts. A sustained, sophisticated capacity building approach – necessary for deeper behavioural change over time – requires a methodological ‘red thread’ and implementers who can navigate these political sensitivities and engage in regular on the ground work to embed and operationalise approaches.

7. Selecting partners with the appropriate mix of skills and experience is thus key; while some of the project implementers that have received funding from the MSIF in Phase 1 meet many of these criteria, others have fallen short. A key criterion for success is for implementing partners to have an on the ground presence, as well as the ability to take UK models or approaches and adapt them to local contexts.

8. Research and evidence-generation is important but needs to be linked to tangible policy or programmatic outcomes. It is promising that many of the MSIF research projects (or research components within projects) sought to use the research generated to influence policy. As such, for all research- focused projects, it is important to build time into project timeframes to sense-check findings with interviewees and engage stakeholders on the final product. Often this process of engagement is just as, if not more, important than the research product itself. Such engagement is sometimes time- consuming but reaps rewards as findings are more likely to resonate with target audiences and thus more likely to lead to follow up actions.

Key recommendations

1. For future phases, the Home Office could consider setting aside additional funding and time for M&E ‘upskilling’ across all the grantees, potentially adding a session on theories of change and results frameworks to the planned grantee workshop in June 2019.We propose the Home Office provides ongoing light- touch M&E guidance and support to all future grantees to ensure a standardised approach to reporting across the MSIF and maximise opportunities to capture results in a compelling and consistent manner.

2. The Home Office may wish to develop more rigorous criteria for assessing implementing partners’ organisational capacities and skillsets, as part of funding criteria, and for ongoing assessment of performance. The projects that included a clear assessment of needs, stakeholder mapping, stakeholder engagement had the strongest foundations. These criteria - alongside an in- country presence and/or strong understanding of in-country dynamics, as well as requisite technical skills - should be a prerequisite for any future grants provided through the MSIF, given that these components align with the evidence on pre-conditions for sustainable impact.

3. Projects’ theories of change could be more explicitly laid out, to include key assumptions and/or underlying evidence, and with clear linkages between activities, outputs and outcomes. Implementers should continue to document any key changes to underlying assumptions as projects progress and include these in the quarterly reports.

4. Methodologies for achieving deeper behavioural change should be clearly articulated and documented, alongside which audience/stakeholders are being targeted (the behavioural change pyramid provides one way of doing so). Overall, documentation should detail the data (or assumptions) upon which certain activities are premised and explain the ‘pathway’ by which activities in key geographical areas of relevance to UK interests will achieve longer term impact.

5. Qualitative as well as quantitative evidence/indicators of behavioural change should be more systematically introduced into results frameworks (some implementing partners are already doing this very well). This could be part of the overall package of M&E support we propose the Home Office provides to all recipients of Phase 2 funding.

6. The Home Office could consider either slightly longer funding cycles for future phases of up to three years, and/or ensure that project partners clearly articulate changes expected in the current funding period versus over the proposed entire lifecycle of the intervention. Proposals for future work could be evaluated against the ‘behavioural change pyramid’ considering how they seek to transform the current situation.

7. Research projects should include time to sensitise stakeholders to findings and build relationships with the policy makers and practitioners responsible for translating research findings into action. Across projects and MSIF grantees, mechanisms could be formed to share lessons more consistently. Suggestions are made throughout the report on mechanisms for doing so, for example the Home Office convening a quarterly/six monthly forum on common issues or thematic areas. Topics include for example, rehabilitation support for victims, as this is a complex issue several projects under the MSIF are engaging with. To contribute to the broader evidence base on ‘what works’, all projects from Phase 1 could be requested to submit an article to the UNU Knowledge Hub on lessons learned from their projects.

Project level assessment

This section provides an assessment of individual projects funded under the MSIF.

Each section includes a score for the extent to which the project, as per the reviewers’ assessment, has achieved the stated outcomes. These assessments draw on data provided by the project grantees as part of their final self-evaluations, and an evaluation of the indicators provided for the outcomes.

The scoring system - drawn from HMG’s guidance on CSSF Annual Reviews – is as follows.

| Outcome description | Scale |

|---|---|

| Outcome exceeded expectation OR likely to exceed, based on good Theory of Change/evidence | A+ |

| Outcome met expectation OR are on course to meet, based on good Theory of Change/evidence | A |

| Outcome partially or unlikely to not meet expectation OR insufficient/unreliable/incomplete Theory of Change/evidence to demonstrate likely contribution to outcome | B |

| Outcome substantially did not meet or unlikely to meet expectation OR no Theory of Change/evidence to demonstrate likely contribution to outcome | C |

Goodweave

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Increased number of UK-linked companies working to end child and bonded labour, who have achieved enhanced transparency across their supply chains | A+ |

| Outcome 2: Reduced prevalence of child and bonded labour in communities/industries with links to UK companies | A |

Achievement of objectives

Upon speaking to project staff and witnessing activities in action it is evident that Goodweave has been able to achieve real impact. There is strong evidence that Goodweave’s methodology can, over time, produce systemic and behavioural change in different stakeholders – ranging from suppliers, to individuals in bonded/child labour, government and middlemen.

It was initially difficult to discern how the different strands worked together/ what the logical chain between activities and outcomes was, as the theory of change was not clearly summarised in the original proposal. While the logical chain did become apparent upon speaking to staff, who can clearly articulate the project’s overall theory of change, this should be more explicitly laid out in future documentation and reports.

Outcome 1: Goodweave has done extremely well in getting new companies in the garment and apparel sectors interested in applying its assurance model and has signed agreements with leading UK brands including Monsoon, with other partnerships e.g. with John Lewis close to formal approval. As such one of the central objectives of the MSIF- funded element of the project has been achieved. As Goodweave itself points out however, this is just the first step of a much more complex endeavour to make sure child or bonded labour issues are identified across a company’s entire supply chain in a certain country, and where appropriate, conflict-sensitive remedial action is taken (simply removing a child or bonded labourer from a factory or place of work on its own is not a solution). Goodweave takes a holistic approach that works preventatively with at risk communities – looping in government counterparts – as well as identifying at risk individuals, and then on remedial actions with individuals who have been in bonded/child labour situations.

Outcome 2: The reviewer took the liberty to begin to rearrange and rewrite this outcome to more clearly demonstrate how Goodweave is contributing to systemic change in communities at risk of bonded/child labour and working on remedial action with those who have already been identified. This is a key strength of Goodweave’s methodology.

Goodweave staff were able to convincingly demonstrate the targeted nature of their educational activities that are operating in communities considered at risk of child/bonded labour, and the strong correlation between access to education and breaking the cycles of child/bonded labour. There are robust systems for identifying, then tracking at risk children’s progress, even if the results of these efforts are not captured as clearly as they could be in reports and the results framework. In future iterations of the project it may be helpful for Goodweave to include qualitative as well as quantitative indicators of behavioural change, and not just in at-risk children but with the other stakeholders it engages with., so as to capture some of the other hugely valuable work that Goodweave does in at risk communities, in collaboration with both businesses and government counterparts.

Broader lessons learnt

Implementing partners must demonstrate excellent understanding of how to identify ‘at risk’ communities and individuals, where these are located, and how to engage effectively with them – evidenced through buy-in from (and change within) affected communities. Those who succeed in doing so – as Goodweave has done – stand a greater chance of generating long term sustainable impact.

Failure to completely achieve some of the desired outcomes and associated indicators is to be expected; given the complexities of addressing modern slavery, and the time it usually takes to achieve sustained behavioural change. However, it is useful for implementers to clearly articulate the overall ‘pathway to change’, even beyond the current funding lifecycle, so that donors can easily understand the desired end state. This also increases the likelihood of donors being willing and able to fund longer-term interventions.

Implementers should look for ways of capturing qualitative as well as quantitative indicators of behavioural change across the various categories of stakeholders they are engaging with.

The Freedom Fund

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Strengthened community structures and empowerment of affected population | A+ |

| Outcome 2: Families are better able to support themselves financially | A+ |

| Outcome 3: Increased civil society capacity for sustained and effective anti-slavery action | A+ |

| Outcome 4: Victims of slavery are liberated (either through one-off rescue event or fundamental changes in relationship with their employer) | A+ |

| Outcome 5: Increased number of arrests and convictions of traffickers and slaveholders | A |

| Outcome 6: Strengthened government safety nets, improved effectiveness of government anti-slavery structures and improved stakeholder coordination | A+ |

| Outcome 7: Heightened public and media attention to the issue (as a necessary catalyst for government action) | A+ |

| Outcome 8: The impact of the program on slavery prevalence is assessed and the most effective and innovative anti-slavery interventions are identified. | A |

| Outcome 9: Programme results, findings on the most effective and innovative interventions, and estimated change in prevalence rates are disseminated to the global anti-slavery community. | A+ |

Achievement of objectives

The project’s overall aims are ambitious, as is reflected by the multiple outcomes that are listed. This is positive; although best practice on theories of change and associated results frameworks would normally advocate for fewer outcomes (3-5 is a rough benchmark for projects of this complexity). Several of the outcomes above would instead be grouped, and those that are arguably outputs rather than outcomes would then feed into those outcomes.

Presentational aspects aside, Freedom Fund and its partners have achieved impressive progress across all the outcomes above. In nearly all cases the project has achieved the results it intended to under the outcome indicators listed. Complete ‘success’ in fully achieving the overarching desired outcomes would, as noted previously, be unrealistic within a two-year project cycle, given the complexity of the issues the project is attempting to tackle.

Freedom Fund’s intervention can be classified as working with broader vulnerable communities, at risk individuals as well as individuals who have already been placed in bonded/child labour or sex trafficking work. As such the project works across the intervention categories in the behavioural pyramid introduced earlier, and looking to tackle modern slavery holistically, which is necessarily a long-term endeavour. Overall, the project represents an excellent combination of leveraging deep contextual knowledge and grassroots engagement (via the local partners) with a strategic lens on how to collectively identify and address key systemic gaps that contribute to or enable modern slavery (provided by the Freedom Fund). For example, the Fund and its partners work closely with government partners to ensure existing legislation and government schemes to address some of the drivers of modern slavery are effectively implemented. There is strong evidence of the project enabling behavioural change in communities, individuals and other key change agents including relevant government counterparts – further examples are provided under the Impact sub-section below.

Broader lessons learnt

A key strength of this project’s methodology is that local partners have been working on community engagement with marginalised, vulnerable populations in India for decades, and already possess productive working with government officials. Freedom Fund provides some of the more technical expertise around modern slavery issues and a ‘big picture’ outlook that helps ensure strategic alignment between different activities, also based on expertise and evidence outside the Indian context.

One of the most innovative elements of the project is the action research methodology the Fund and its partners use. This approach trains local facilitators (sourced from target at risk communities) to help communities themselves identify the issues in their community that have resulted in them being drawn in into bonded/child labour and trafficking.

Communities determine concrete ways of collectively tackling the issues. This focus on at- risk communities empowering themselves is truly transformative. The principles of this approach could be applied to several other complex problems that HMG interventions are seeking to solve.

The Freedom Fund and its partners do not underestimate the challenges in seeking to effect sustainable change. However there is much merit in the ‘hotspot’ approach adopted, which provides intensive support to a handful of at risk communities at a time to allow them to ‘exit’ out of modern slavery, while working with government officials to fulfil their role more effectively and ensure feedback loops between on the ground activities and policy-level engagement.

NSPCC

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Increased capacity of professionals and community to identify forms of child Modern Slavery | B |

| Outcome 2: Involving children and young people in anti-child trafficking work to influence and raise awareness of child modern slavery | C |

Achievement of objectives

The impact of this project is most apparent in the raising of awareness of child modern slavery. As a result, a wide range of professionals are now equipped with the skills to identify victims of trafficking and exploitation. In northern Ghana, the project has also been effective in preventing children from travelling and being at risk of exploitation and abuse. Other elements of the project have not been as successful as hoped for the reasons discussed below.

While the reviewers note that a theory of change wasn’t a requirement of the project, results have been mixed because core assumptions, intermediate steps and components of the overall project design and theory of change have shifted or have not been fully articulated.

NSPCC had to adjust their original project proposals, and as a result the parameters of the project have changed. In the case of Vietnam in particular, there appear to be different views as to the scale of child trafficking concerns vis a vis UK interests and how best to address these. A key lesson here is that HMG and implementers should ideally develop a shared, evidence-based, understanding of the specific problems a project seeks to address early in the implementation process. Any subsequent changes to underlying assumptions should be documented.

Methodologies/activities underpinning outcomes were not fully fledged, or could not be conducted, and as such outcomes have been marked down. For example, ad-hoc training alone is unlikely to achieve more strategic behavioural change outcomes in frontline practitioners – while they may be better placed to identify forms of child modern slavery, transforming this into action to tackle modern slavery requires additional activities. NSPCC’s overseas presence and its reliance on local partners means there were gaps between activities and the overall impact of the project has not been as strong as hoped.

Broader lessons learnt

The project is focused on awareness raising, primarily engaging in activities that fit within Category III of the behavioural change pyramid. This is necessary because of the limited response in both Ghana and Vietnam, which means significant groundwork is required to encourage action. However, more effort is required in Category IV to ensure measures are in place to respond appropriately when cases are identified.

NSPCC engaged in a variety of activities to raise awareness of child trafficking and exploitation. The approach to awareness raising was multifaceted – training professionals to be able to identify forms of child modern slavery, sensitising communities through interactive theatre, targeting children in schools through clubs and through the creation of core groups. Overall the project experimented with different approaches to varying effect.

While the project had some success in raising awareness, challenges arose when turning this awareness into action. In Northern Ghana, where tackling modern slavery means preventing children from travelling there was more scope for success. However, in Accra where children have already been trafficked/ exploited, there are few formal mechanisms to respond, which undermines identification.

While awareness raising is an important component of the response to modern slavery, this type of programming needs to be accompanied by an analysis of the pathways to support when individuals are identified. When none exist, or those that do exist are inadequate, as in the case of Ghana, projects also need to include activities that seek to change this. This could include advocacy to improve the government response, direct service provision, or partnerships with service providers.

Sustainable capacity building requires an ability to embed policies and/or processes and elicit, at multiple levels, behavioural change within local actors or institutions responsible for owning activities. This in turn requires implementing partners to have an on the ground presence, as well as the ability to take UK models or approaches and adapt them to local contexts. Experience (and evidence) from across the international development sector shows that technical expertise alone is not sufficient in generating lasting outcomes in complex environments, and that interventions must be responsive to the political economies of the target countries.

Pacific Links Foundation

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Human trafficking awareness media campaign, educational film and outreach activities raise awareness of human trafficking in Vietnam and UK | B |

| Outcome 2: 70% of 120 recipients graduate from vocational training programs | A+ |

| Outcome 3: Increased skills and improved capability of law enforcement and criminal justice agencies to identify and prevent modern slavery and protect victims | C |

| Outcome 4: Factory workers decrease vulnerability to HT, with training participants reporting improved knowledge on human trafficking definition, risks, how to protect oneself, how to report it, and alternatives to going overseas to seek work | B |

| Outcome 5: Financial literary app decreases vulnerability to trafficking | C |

| Outcome 6: Increase evidence base on trafficking from Vietnam to the UK in English and Vietnamese | A |

| Outcome 7: Strengthened knowledge of key stakeholders on trafficking of Vietnamese children and adult perpetrators/victims and routes including transit countries | A |

Achievement of objectives

Overall this project has had a mixed performance. The youth awareness raising sessions are the strongest element of the Foundation’s activities. These sessions and accompanying footage/campaigns have certainly reached large numbers, and the Foundation has done well to increase coverage through celebrity ‘influencers’.

However, the project would have benefitted from focusing on fewer desired outcome areas, and more closely defining exactly what it wished to achieve, and by what means, in those areas. The intermediate steps, preconditions and assumptions underpinning the project’s theory of change – or put another way, the methodological ‘red thread’ behind different activity strands – need to be further articulated. Both the Home Office and Pacific Links could have made intermediate steps or results (usually referred to as outputs) more clearly defined, and strengthened the indicators.

Broader lessons learnt

Project documentation must articulate the logical thread between the problem or need activities are trying to address, and how and why the activities are best placed to address those problems. Where possible these must be based on evidence, or at minimum clearly defined hypotheses. This helps implementers continually test, and adjust, programming components as a project progresses. It also helps donors and other key stakeholders understand what progress is being achieved.

Modern slavery is a complex phenomenon. It is critical to match ambition in terms of desired outcomes with the necessary resources (human as well as financial) and capabilities, in terms of implementing partner skillsets. While specifics will depend on the context and precise problems a project is trying to address, often the ‘best’ projects in this space are relatively small-scale to begin with and look to pilot and test approaches before seeking to scale up or expand into multiple activity areas.

Retrak

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Increased awareness among children of how to avoid becoming a victim of modern slavery and increased awareness among caregivers and community members of how to protect children from becoming victims | A |

| Outcome 2: Police officers and Prosecutors are engaged in the issue of child exploitation and discuss ways of addressing it | A+ |

| Outcome 3: Victims (children who have migrated and/or are in exploitative domestic work) show improved wellbeing after receiving support services and/or being placed in a family context (family or alternative care) | A |

| Outcome 4: Stakeholders (employers, domestic workers and brokers) demonstrate an improved understanding of modern slavery | A+ |

Achievement of objectives

Outcome 1: The MTR reported that this outcome was partially on track, and in the final year of the project it has been fully achieved. This trajectory is to be expected as it takes time to establish self-help groups and child protection clubs, and they need to be firmly in place before any impact is achieved.

A self-help group in Offa woreda was visited during the evaluation. At the outset, the group was hesitant to form as there has been negative experiences with similar programmes, but they now report that they couldn’t go back. The group visited had been active since November 2017 and members reported that by saving and becoming more economically stable, they were able to keep their children in school. The savings books showed that the amount members had been saving increased over time, and 9 members had taken loans – one to pay her son’s university fees, one to open a shop in the community, and another to buy a goat. Members reported an attitude change – as a group they encourage each other, and where previously they didn’t care if their children left the village, they now encouraged them to stay in school. The self-help groups are evaluated by Retrak by providing stories of the most significant change, which is agreed upon by the group.

Yakima primary school in Offa woreda was also visited, which has a child protection club. The school has recorded a decrease in drop outs – from 5% in 2008 to 1.7% in 2018/19. Mentors for the club have been trained on children’s rights, assessing the needs of children and how to organise the club. The club discusses life on the street and how to teach other children – presenting on assemblies through drama, music and news. There is also engagement with local government leaders, community leaders and parents.

The child protection clubs have had a gender imbalance, highlighted in the achieved target for indicator 1.2. While this doesn’t undermine the objective as a whole, Retrak did identify why girls were less involved and have taken steps to address this, empowering them to become more active. However, the timeframe of the project was too short for the numbers to change significantly.

Outcome 2: Training was provided to prosecutors and other professionals in year 1, but the state of emergency prevented the release of police for training. A 3 day workshop was held in November 2018 with 22 police in attendance. The workshop ended up being a high-level events with the Greater Manchester Police involved, also including the regional police commissioner, Attorney General’s department, the Anti-Trafficking Taskforce and the Better Migration Management programme. The workshop facilitated linkages on trafficking and slavery.

Outcome 3: Girls escaping domestic servitude or commercial sex work are accommodated in Lydia lighthouse and receive holistic care – shelter, food, health care, catch up education, life skills training and psychological support. Stays at Lydia Lighthouse are intended to be short – 2-3 months – before reintegrating the girls back with their families. Accordingly, the programme is intensive, but closely monitored to ensure girls wellbeing is improving. All of the girls have wanted to go home, so the team engages in family tracing, and then conducts parenting training and provides support to families through livelihoods training. Follow ups are conducted every 3 months for 2 years to ensure girls are adapting and remain in school. The support is intense, so can only target a small number of girls, but the outcome is more sustainable as a result.

Because the centre relies on referrals, the process of identifying girls was slow to begin with, as exploitation of girls is not a widely discussed issue. However, the numbers of referrals have steadily increased as other activities were conducted to increase awareness of domestic work and exploitation. It is likely that Retrak will achieve or come close to achieving the target. However, the quality of support provided has been high, with very experienced and committed staff in Lydia Lighthouse. Safeguarding issues have also been thoroughly considered, with policies and procedures put in place.

Delivery of the project has also been hindered by the political situation in Ethiopia. A State of Emergency was in place between February and June 2018 after the Prime Minister resigned, which made several activities difficult, particularly reintegration of girls as Retrak staff couldn’t leave Addis Ababa. The inability to travel also meant Lydia Lighthouse was unable to take new girls.

Outcome 4: Community conversations were held between August and December 2018. Although the numbers suggest the project has exceeded their target dramatically, not all participants attended all of the sessions. However, there is a large number of participants that did, and a joint community conversation was held in December 2018 to bring all of the stakeholders together. During the evaluation visit, a focus group discussion was held with a cross section of employers, domestic workers, brokers and facilitators. Although there may have been some challenges to domestic workers speaking freely in the company of their employers, there were reports that the relationships had improved – from both the employers and domestic workers. Brokers had an increased awareness of the rights of domestic workers, as did employers, and an agreement had been developed as a result of the community conversations to formalise the relationship and set out these rights to minimise the risk of exploitation, the agreement is signed by the employer and domestic worker.

Broader lessons learnt

Drawing on previous experience working with street children, the theory of change deems that the creation of a culture where child rights are acknowledged, making domestic work legal and rights respecting will result in sustainable change where domestic work is managed and young girls are not exploited. This is a softer, long-term approach that cannot be achieved in two years. The balance of individual support and strategies to transform the dynamics of domestic work begins a shift to achieve this, but it will take more time to consolidate the shifts. For example, with the Self-Help Groups, year 1 created social cohesion among group members, year 2 is when the economic benefits began to be realised, but it will take another year or two for these results to be multiplied and cemented. This is not a criticism however, as these types of interventions take time to consolidate as noted earlier, and within the project timeframe significant results have been achieved that fit within category I and II of the behavioural change pyramid – indicating a targeted approach to changing attitudes and behaviours.

There a several lessons to be drawn from Retrak’s project:

-

Implementers that are already working in the country/ area of implementation have a good understanding of the context and dynamics within which they will be operating. In Ethiopia, this ensured the project was able to navigate the political changes that occurred in the country over the implementation period, but also that the activities were based on lessons learned from other projects.

-

Projects with a simple theory of change, with multiple strategies to achieve that theory of change are the most effective. This type of approach allows for strategies that progress at a different pace, and target different levers, but contribute to an overarching aim.

-

Projects that engage with all categories of the behavioural change pyramid to an extent have the most potential for sustainable change. By engaging multiple levers, Retrak didn’t expect to achieve the desired outcome through one avenue, but from several approaches coming together. Targeting different stakeholders also creates a momentum for change.

The Salvation Army

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Increased awareness of and changed attitudes and behaviours towards modern slavery within target communities | A |

| Outcome 2: Reduced re-trafficking of and increased quality of life for victims of modern slavery | A |

| Outcome 3: Improving the evidence base through enhanced understanding of Modern Slavery in-country and sharing best practice responses | A |

Achievement of objectives

Outcome 1: One very positive element to the TSA approach in the Philippines is that they engage closely with government counterparts. For example, awareness raising is done via municipal officials who help select schools. However, as noted under the Relevance section below, targeting (and messaging) could be improved. For schoolchildren/minors, the key issue is the potential for online sexual exploitation rather than being trafficked/ending up in exploitative labour for example. With vulnerable communities where people (largely women) leave to become domestic workers and end up being exploited, there is a sense that some individuals in communities may be more aware. However, that does not stop them taking exploitative jobs again in future, and others in the community are still mostly unaware of the risk of exploitation. Breadth has been achieved in terms of the number of events, but this does not equate to depth or translate to deep behavioural change in the most vulnerable or at-risk communities. While it would be unrealistic to achieve such deeper change in two years, thought should be given as to how this might be factored into future phases, for example through maximising the Anti-Slavery Champions and honing in on more vulnerable communities and galvanise communities to take more action/responsibilities themselves (see later recommendations on this point).

In Nigeria, the process of raising awareness was also slow to start, with the first year focused on building relationships in order to create platforms for awareness raising. This delay however was quite useful, as it gave time for the research to be conducted, which created a better understanding of the dynamics and context and allowed for the approach to become more targeted. This was evident in Ivue, where the emphasis was on young men seeking to travel to Libya. Accordingly, awareness raising focused more strongly on that than sexual exploitation of women and girls in that location. As with the Philippines, a large number of events have been held, but this has not resulted in large scale behaviour change. However, given the previously positive community perception towards trafficking, the shift to understand the risks is a significant step along the behavioural change spectrum and indicates a need to maintain the approach to galvanise community perceptions and behaviours. The result of the awareness raising has resulted in an increased reporting of cases, but this cannot solely be attributed to the project, as other initiatives are also underway.

Outcome 2: The wording of the overall outcome statement, particularly regarding re- trafficking, needs to be reassessed as the MTR noted. However, within the ‘indicators’ set out in the results framework, TSA has achieved good progress. As the host family model was new and innovative, slow take up is to be expected, as these types of models take time to ‘bed in’. Spending time on generating trust is essential to the long-term success of the intervention and as such TSA has built very strong foundations for future success. To mitigate the initial lack of take up for the host family programme, TSA was able to leverage its network of officers, drawing on TSA’s foundation as a membership organisation where members volunteer their services for public good. Even with TSA members there was initially reluctance to be involved, but once the programme was up and running, the feedback from both host families and survivors has been positive. Also, seeing the model in practice has also encouraged other families outside the TSA network to volunteer for the next round of training. As such, it appears that after a slow start, host families are gaining momentum. This will need to be monitored in future, but if successful it presents a low cost and more tailored alternative to direct support.

Outcome 2 also provided recovery support for survivors, including psycho-social support, as well as recovery support through business set up, skills training, education and employment support. The TSA approach differs from other livelihoods approaches in its individualised case management approach that identifies the needs of each individual. There are also 12 months of follow up support, which for businesses that are set up includes a focus on business strategy, marketing etc to increase profits. While only 33% of survivors are self-reliant in 12 months, this is a significant achievement and is more an indicator or over-optimism at the beginning of the project than a failure of the strategy.

Outcome 3: The situational and needs analysis in Nigeria was essential in order to tailor the activities of the project, and its approach has been strengthened as a result. The conferences have been held, but their usefulness is unclear, and in Nigeria the resources for another conference were redirected towards capacity building for students and teachers, as it would have a greater impact. The creation of stakeholder networks is still a work in progress. In Nigeria, the Joint Stakeholder Forum has improved referrals, created a data bank where organisations submit reports, and increased collaboration among organisations under the direction of NAPTIP. In the Philippines, TSA enjoys very good relationships with government officials and structures engaged on anti-trafficking (see e.g. the PIACAT structures referenced in the results framework). It was clear that government counterparts view TSA as adding value to their own efforts to tackle labour exploitation. The grassroots community meetings are an area for future improvement.

Broader lessons learnt

TSA’s approach is based on a theory of change that believes empowered and resilient communities and survivors are protected against human trafficking. The project assumes that guided awareness and advocacy will change the attitude and behaviours of communities to become more protective and supportive; the agency and wellbeing of survivors will improve through engagement with support services and host families; and the response will become more coordinated through partnership. The desired outcomes are ambitious in both Nigeria and the Philippines. In Nigeria, communities have often been supportive of trafficking because of the remittances it brings and disapprove of survivors coming home empty-handed. In this context, the work of TSA has moved communities along a spectrum of attitude change, and sustained engagement will move into behaviour change.

The preventative work mostly engages with category III of the behavioural change pyramid – taking a broad approach to change community perceptions towards trafficking. However, the work with AHT champions and action groups moves in category II as it is more targeted and aims to create action. Direct assistance fits within category I, and work with government and non-government stakeholders engages with category IV. Accordingly, the project is holistic, engaging at each level to the extent possible.

The implementation of TSA’s model in Nigeria provides an example of how to engage with an intractable problem. Particularly as many people view human trafficking positively, it is difficult to find entry points to change perceptions to the extent that trafficking is reduced. The TSA project was based on a granular understanding of the dynamics of the trafficking industry in order to identify how to move communities step by step along a spectrum of behaviour change, starting with perceptions towards trafficking and edging towards behavioural change.

As with Retrak, engaging with multiple levers and target groups across the four categories of the behavioural change pyramid was also effective for creating sustainable change by not relying on one target group. There is potential that each target group will also spur on action among other target groups.

Stronger Together

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: An increase in responsible businesses in the South African fruit and wine sectors that know how to prevent and tackle modern slavery in their supply chains, and enhance their collective responses by sharing best practice | A+ |

| Outcome 2: Increased engagement between international retailers/buyers and suppliers in the South Africa fruit and wine industries leads to changes in business practice that will help to prevent and tackle modern slavery | A |

| Outcome 3: Decrease in vulnerability to becoming a victim of modern slavery of workers in the fruit and wine industry in South Africa | A |

| Outcome 4: Enhanced understanding of prevalence and nature of modern slavery in South African fruit and wine sectors | A |

Achievement of objectives

As with many of the projects, the results framework does not do justice to the achievements of the projects, which can be broken down into three complementarity approaches set out below. The primary challenge in measuring the results of outputs 2, 3 and 4 is on how this is measured. Stronger Together’s project can be organised around three pillars.

1. 1Stakeholder leg, which broadly corresponds with outcome 2. This involved the establishment of three steering groups:

- international retailers and international importers/exporters (e.g. Berryworld) and a South Africa retailer (Woolworths)

- A local business forum meets every six weeks and brings together the key industry bodies (VINPRO, SIZA, WIETA) and South Africa businesses (e.g. Ceres Cascade Farms)

- A Multi-stakeholder forum meets quarterly and was established to bring together remedy partners, Department of Labour, Department of Agriculture, trade unions and academics

- Establishing these networks took longer than anticipated because of the scepticism towards labour exploitation, but their establishment has been essential to develop a collaborative approach that involves all of the different players.

2. Awareness leg, which corresponds to outcomes 1, 3 and 4. This included the 62 workshops for producers and senior managers. As with the stakeholder leg, uptake was initially slow, but demand increased as the project progressed, with the final workshops being oversubscribed.

3. Remedy leg – this was developed throughout the project, arising from the recognition that without recourse the first two components were not as powerful. Stronger Together identified existing mechanisms that could respond to labour exploitation, developing remedy pathways – on farm remedies, industry remedies and provincial/ national remedies that tapped into the human trafficking helpline as well as a special law enforcement unit. Remedy workshops were delivered in 6 provinces. Remedy was also built into the workshops, encouraging participants to identify exploitation and consider how to deal with the case.

Broader lessons learnt

Stronger Together’s approach was based on a holistic theory of change – increase awareness of the topic by using the right stakeholders to get the right people in the room for the right training, give that training sustainability with a remedy and exploitation will decrease.

Because of the starting point, much of what Stronger Together has been able to achieve has been attitudinal change across the wine and fruit industries (category III). However, working through SIZA and WIETA linking modern slavery to the audit process (category II) and providing remedies (category I) begins to create behaviour change. However, moving fully along this spectrum will take longer than the 2 years already implemented.

As with NSPCC, the core focus of Stronger Together’s approach was on awareness raising to get labour exploitation higher on the agenda before pushing for change too fast and too soon. However, the key lesson from Stronger Together’s work is that this needs to be paired with additional activities to create structures to support behaviour change. Primarily this was done by providing straightforward guidance to businesses on the steps they can take to reduce the risk of forced labour in their business and supply chain. The project also developed remedy pathways, also moving towards measures to assess compliance with modern slavery requirements.

Another lesson was how to approach modern slavery in a rigorous way that requires behavioural change in a way that is non-confrontational and brings key partners along. The project delivery partners SIZA and WIETA are associated with auditing, but the project was framed as ‘beyond audit’, with the aim to be supportive of business ensuring their involvement through steering groups that shared learning and best practice.

Research projects

Note that the reviewers did not speak to stakeholders other than the research partners themselves: as such all the comments below are based on phone interviews with relevant project managers and a review of available documentation. Saskia Marsh undertook the reviews of the St Mary’s University and UNU projects, given Sasha Jesperson’s previous involvement with both.

St Mary’s University

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: the report addresses gaps in the existing evidence base on effective law responses to trafficking and slavery | A+ |

| Outcome 2: dissemination of evidence gathered to inform effective law enforcement responses | A |

Achievement of objectives

Overall this project has the markings of a low cost, yet highly relevant research project that provides the Home Office and other interlocutors with useful data on which to base future policy/programming decisions.

As can be seen from the table above and reflecting points made in the MTR, at which point the project was already close to completion, this research project has achieved intended targets under outcome area 1. The research undertaken by St Mary’s was in response to a clearly defined needs/knowledge gaps, and the University has made good use of its Advisory Board (drawn from across HMG, the private sector, victim support organisations and subject matter experts on anti-trafficking) as a means of ensuring the research remained responsive to those needs.

On outcome 2, as the university itself noted, there is more that could be done to ensure the research generated is leveraged to inform/influence law enforcement responses. (Note that additional funding and time/effort to arrange the necessary fora for additional information exchanges would be necessary for this outcome area be met more fully; and for the small amount of money the project has cost the Home Office, it has already performed very well).

St Mary’s stated that it had received very positive feedback from some in-country interlocutors upon presenting its findings, and that there was evidence of the research generating not just new knowledge but the potential for new responses from law enforcement agencies. For example, German law enforcement interviewees stated that because of the research they saw an increased need for collaboration with UK counterparts.

Broader lessons learnt

For all research-focused projects, it is important to build time into project timeframes to sense-check findings with interviewees and engage stakeholders on the final product. Often this process of engagement is just as, if not more, important than the research product itself. Such engagement is sometimes time-consuming but reaps rewards as findings are more likely to resonate with target audiences and thus more likely to lead to follow up actions. This applies across all research projects.

University of Bedfordshire

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Existing knowledge and evidence on vulnerabilities and resilience to human trafficking to human trafficking in Albania, Nigeria and Vietnam is consolidated, synthesised and shared | A+ |

| Outcome 2: The research project builds on and contributes to the existing evidence base on vulnerabilities and resilience to human trafficking in Albania, Nigeria and Vietnam and the support needs of people who have experienced human trafficking are better understood | A+ |

Achievement of objectives

University of Bedfordshire/ IOM’s research was inductive from the outset, seeking to create a rich, nuanced and contextual understanding of human trafficking – exploring, mapping and seeing the big picture. The project used the IOM case work model as a research framework to map individual lived experiences and used a timeline to map the structural changes that have influenced trafficking from the three countries.

The Shared Learning Events sought to engage with the indigenous evidence base, using the knowledge of local researchers and organisations. These events aimed to assess what was already known before data collection enhanced the evidence base.

The ethical approach developed by the research team contributed to the modern slavery response, as there are few guidelines on how to engage in research, particularly with individuals affected by modern slavery. University of Bedfordshire/ IOM developed ethical scenarios and unpacked how to do research and the potential of interpersonal violence with the aim of building a culture of ethics with stakeholders engaged in the project.

United Nations University

| Outcome | Score |

|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Creation of a global knowledge platform for data and policy evidence that is used to support the work of stakeholders, especially policy-level actors, tackling modern slavery | A+ |

| Outcome 2: Growth of understanding of evidence base on ‘what works’ in tackling modern slavery | A+ |

| Outcome 3: Impact of the Platform on policy-level choices | A+ |

Achievement of objectives

This is an ambitious (and relatively expensive) project, but one that has made very good progress in providing a highly visible home for high calibre research connected to the modern slavery agenda.

Built into the theory of change is the notion that the research should lead to influencing how governments and other stakeholders address modern slavery issues. This is positive, and the project has begun to make good progress towards this goal too. As such it is more than ‘just’ a pure research project and it is clear much thought has gone into ensuring the project, over time, achieves more strategic outcomes that seek to achieve behavioural change, in terms of improved decision making, in policymakers and practitioners. The reviewers can only encourage more of these ‘research plus’ style interventions.

The associated results framework for the project and indicators employed are well constructed and robust, and again emphasise that the project does not seek to simply generate research for research’s sake. Across the outcome indicators under outcome areas 1, 2, and 3 the project can be said to have achieved its intended targets in the current phase, while recognising that there is still some way to go until the platform achieves deeper results linked to the outcome areas. This is perfectly understandable: it will take more time than the two-year span of Phase 1 funding for the platform to really impact policy-level choices, especially as there were some delays in getting the platform up and running, for example due to UN procurement rules.

There are potential small areas for improvement in future phases, depending on whether this is feasible and time/cost effective in making some of the indicators even more accurate. For example, measuring clicks and downloads is a good but somewhat general indicator; ideally as many indicators as possible would be able to demonstrate how the more specialised target audience for this platform (policy-makers/practitioners) are accessing and using the platform. The other indicators already do so very well.

Annexes

Annex 1: Terms of Reference

Background and context

1. The Home Office’s Modern Slavery Innovation Fund (£11m from 17/18-20/21) makes grants to NGOs, universities and international agencies to incentivise the development of innovative ways of tackling modern slavery. The objective of the fund is to build the evidence base on tackling modern slavery and identify what works.

2. There are currently 10 projects being funded, accounting for £6m of the Fund and running for two years up to March 2019. These involve seven intervention projects (addressing modern slavery ‘on the ground’ in Africa and Asia) and three research projects (two academic papers and a new UN ‘Knowledge Platform’). The intervention projects include victim support and awareness-raising by the Salvation Army in Nigeria and the Philippines, child protection capacity-building by the NSPCC in Ghana and Vietnam, and supply chain mapping by the NGO Goodweave.

3. To assess the extent to which these projects have achieved their aims and intended impact, and to identify lessons to inform future programming, the Home Office is commissioning an end of project review to be completed in Spring 2019.

4. A mid-term review took place in Spring 2018 which focussed on the performance of the projects in each area of activity and lessons for the second year. This review found that nine out of ten of the projects were on track to deliver planned outcomes.

Purpose

5. The primary purpose of the review is to assess the performance and impact of the MSIF projects against their stated aims and objectives in order to draw out lessons and what works to address modern slavery to inform future HMG and other partners modern slavery programming.

6. The primary audience for the review is the Home Office and its MSIF programme partners. The review will also be shared with other HMG departments, the wider donor community and organisations working to tackle modern slavery.

Scope and objectives

7. The end-line review has the following objective: Provide the Home Office, programme implementers and other relevant stakeholders with an assessment of the performance of the projects funded by the MSIF, and with relevant and actionable recommendations and lessons as to which types of projects, innovations and activities show the most promise for tackling modern slavery.

Timing, expected outputs and indicative work plan

8. The review will be carried out during the final months of the project’s’ delivery in early 2019. It will be split into three phases: initial desk review, country visits and synthesis/report writing. Indicative timelines and deliverables for each phase are outlined below.

9. The primary output for this work will be a completed review document, no longer than 70 pages. This should include an executive summary and prioritised table of recommendations. This is excluding annexes. There may be scope to present findings at a dissemination event(s).

| Timeline | Task | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 21st Jan-1st Feb | Document review | Inception/methodology note (to include detailed review questions, data collection plan/ field visit plan and interview topic guides (to be signed off by Home Office/SU M&E adviser)) |

| 18th Feb-18th March | Project visits: Interviews (likely 7 countries to be visited) | - |

| 29th April-17th May | Synthesis/Write-up | Draft report submitted |

| 20th-31st May | Final drafting | Final report, presentation of findings to key stakeholders (TBC) |

Indicative Review Criteria and Questions

10. The review will assess the Phase 1 interventions against the following criteria. High level sub questions are provided for each, but these will need to be developed further in discussion with the Home Office MSIF team. Each criteria has been given a weight to demonstrate the approximate focus that should be placed on each during the review.

|

Criteria |

Questions |

Weight |

|---|---|---|

|

Relevance |

(Fund level) Did the projects aims and objectives remain consistent with the objectives of the MSIF, and broader HMG objectives on modern slavery? (Project level) Were the interventions selected (and their intended outcomes) relevant and appropriate for the communities/individuals targeted? |

20% |

|

Effectiveness |

(Project level) Have the projects achieved the outputs and outcomes as set out in their results frameworks? (Project level) Which areas of activity have been most effective in achieving their outcomes? (Fund level) To what extent have the projects contributed to the six objectives set out in the Modern Slavery Innovation Fund? (Fund level) How well has the fund performed in its objective to test innovative approaches to tackling modern slavery in order to build the evidence base? |

30% |

| Efficiency (Cost effectiveness/VfM) | (Project level) Do the outcomes of the projects represent value for money? (Project level) Are there any good/best practice examples of efficiency demonstrated by the projects, what can be learned from these? |

10% |

| Impact | (Fund level) What contribution has the investment in these projects made to the evidence base and understanding of what works in tackling modern slavery? (Project level) How impactful has each project been? (Project level) Have there been any unintended outcomes (positive or negative) as a result of the projects? (Project level) What were the particular features of the projects that made a difference? |

20% |

| Scalability/Sustainability | (Project Level) Are the benefits of the projects likely to be sustained after the projects end? (Project level) Are there specific project elements/activities that could be transferred to other countries/contexts? Are there specific project elements/activities that could/could not be delivered at scale? (Fund level) To what extent are lessons from these projects able to inform future modern slavery programming? |

20% |

Cross-cutting issues

11. The review should also consider cross-cutting issues where relevant, particularly in relation to issues of gender, power relations, marginalisation and human rights.

Methodology

12. The review will include a mixture of desk-based document review, with site visits and interviews with project stakeholders (and beneficiaries where possible and ethically viable) to answer the review questions above. The desk-based review will primarily look at results frameworks/project plans and quarterly reporting products and should be used to identify specific themes, outcomes and/or issues to be explored in more depth through interviews with key stakeholders and beneficiaries during project visits. The findings and analysis from the desk-based review will be synthesised with those from the interviews to draw out overall findings and recommendations. Concurrently to this review, some of the projects will be conducting their own end-line reviews/evaluations. The synthesis/write-up phase of this review has been delayed until May to allow this overarching review to draw on the findings of the project level evaluations.

Data

13. The data available is primarily comprised of qualitative narrative reporting, with some basic quantitative management information data. The level of information is variable across the 10 projects. Some of the projects are already planning, or may decide to conduct their own end-line evaluations at project level. It is not clear at this stage if and when this information will be available to the reviewers, though it is most likely to become available after the country visits are completed, during the synthesis and write up phase.

Annex 2: Methodology

The end-line review of the MSIF will engage with projects at two levels. The first assesses the delivery (outputs) of the individual projects, and the second engages with the outcomes.

Outputs

Indicators in the results framework will be used to assess the outputs of the project. In addition, OECD DAC criteria will be used to assess the projects, evaluating relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability. These criteria will be assessed through a review of documentation and a deep dive into the seven implementation projects. Deep dives will involve field visits to project countries. Interviews will be conducted with key personnel at the British High Commission/Embassy that supported the project (where relevant), project teams, project partners or stakeholders, and beneficiaries (more detail of specific interviewees are included for each project below).

For the research projects, interviews will also be conducted with project teams, project partners or stakeholders, and beneficiaries, either in person of via Skype. Projects will be evaluated broadly based on the questions below. Specific questions will be tailored to each project based on their results framework, as well as the person being interviewed.

High-level framework and questions for project reviews

Relevance

Were the interventions selected (and their intended outcomes) relevant and appropriate for the communities/ individuals targeted?

How was the local context in which the project was to be delivered incorporated into project design?

Effectiveness

Have the projects achieved the outputs and outcomes as set out in their results frameworks?

Which areas have been the most effective in achieving their outcomes? How is the target audience defined? What is the right one?

How have the projects responded to the recommendations of the mid-term report?

Efficiency

Do the outcomes of the projects represent value for money?

Do the project’s activities draw on existing evidence and evaluation of good practice?

Are there good/ best practice examples of efficiency demonstrated by the projects, what can be learned from these?

Impact

How impactful has each project been?

Have there been any unintended outcomes (positive or negative) as a result of the projects?

What were the particular features of the projects that made a difference?

What M&E systems have been put in place to measure project performance and impact, including results frameworks? Are these sufficient and robust?

How much has each project changed behaviour and how is that measured/evidenced in the data collection/results frameworks?

Sustainability

Are the benefits of the projects likely to be sustained after the projects end?

Are there specific project elements/ activities that could be transferred to other countries/ contexts?

Are there specific elements/activities that could/ could not be delivered at scale?

How were risk factors identified in a robust manner? To what extent do projects adhere to a ‘do no harm’ policy?

Outcomes

To understand how the projects have contributed to the MSIF objectives and identify lessons that contribute to a better understanding of what constitutes best practice responses to modern slavery, the deep dives will also use outcome harvesting. This methodology offers insights into (i) what results/outcomes a programme has achieved, (ii) why the result was achieved, (iii) what else could have led to the identified results, and (iv) what more we can do to get to our impact. The outcome harvesting methodology is designed to generate insights:

- in the form of verifiable evidence from programmes that deliver ‘softer’ types of outcomes,

- on outcomes that are not easily predictable at the start of a programme (those for which we cannot create hard indicators),

- where outcomes are delivered through multiple influences/activities (some outside the scope of the programme itself, for example), and

- to help map the change pathways used within the logic of the programme to identify where there are gaps between the activities and intended outcomes.

The hybrid methodology we are proposing is qualitative in nature and relies on an appreciative inquiry approach in the way that questions are posed to respondents (both for surveys and interviews). This methodology relies on questions that are open and elicit reflection on broader aims. It offers insights on what has led to results (contribution rather than direct attribution of activities), thereby generating evidence of what works and why.

Annex 3: Defining impact – a potential framework for exploring types of behavioural change

Most of the projects in some way seek to influence behavioural change. Contextual factors dictate the starting point and how much effort is required to achieve that change, who should be targeted and how. In order to the understand the impact of the MSIF it is useful to consider how projects contribute to behavioural change.

The figure below is an intervention pyramid (adapted from the counter terrorism/countering violent extremism space)[footnote 2] which provides a useful means of visualising what sort of behavioural change an intervention is seeking to achieve. There is strong evidence that well-designed interventions that seek to achieve systemic/holistic change, involving multiple stakeholders, are more likely to be successful in the long term.

As explained by the pyramid behavioural change interventions may be viewed along a spectrum, with different target audiences, timeframes and intervening stakeholders. Each context will define what is possible, and where interventions should be focused. For example, in South Africa, labour exploitation has not been viewed as a serious problem, so before any direct interventions were implemented, a significant amount of awareness raising was required to raise labour exploitation as an area of concern.

At one extreme is broad-brush work to deal with underlying factors in the long-term (bottom of pyramid). At the other are very targeted interventions focused on immediate action to interdict behaviour already underway (top of pyramid). A fourth category lies outside the pyramid but overlaps with the other categories within the pyramid, is around engaging with policymakers and other structural power holders or brokers on modern slavery issues. Here it is the behaviours of these policy makers/institutions/relevant government counterparts that an intervention is seeking to change.

- Category III initiatives are preventative. They take a broad-brush approach and target the wider community where there are already indicators of an issue associated with modern slavery occurring. While this is an important category to better understand the dynamics and gain greater traction for modern slavery, this category is a precursor for change in the other categories.

- Category II initiatives are transformative. They aim to target ‘at risk’ individuals who are most vulnerable to being recruited into modern slavery, seeking to prevent exploitation by challenging the permissive environment.

- Category I initiatives are ameliorative, engaging in environments where modern slavery has already taken place. These initiatives engage with and rehabilitate individuals who have already been subjected to modern slavery. Many projects will need to engage with this category, while also seeking to transform the situation by engaging in categories II, III and IV.

- Category IV, which lies outside the pyramid comprises initiatives which, at a macro level, shape and create policy frameworks/processes associated with tackling modern slavery. The primary target audience is state actors and potentially civil society organisations who are invited to take part in policy discussions. Engagement in this category alongside the others is crucial to achieving long-term structural change.

Best practice takeaway: The more impactful projects funded by MSIF work across several categories in the behavioural change pyramid, seeking to engage with multiple levers to transform the dynamics of modern. However, engaging in behavioural change depends on the starting point and the appetite for change. In some contexts, significant broad-brush awareness raising may be needed (i.e. engagements may need to begin in category III) to create an opening for more substantive change or more direct engagement with at-risk individuals (i.e. move ‘up’ the pyramid to categories II and I).

The various categories require distinct methodologies as the type of behavioural change and the primary audience is different. The more sophisticated projects were able to develop tailored methodologies for each category. Again, the potential for this depends on the context. Future projects should be encouraged to engage across the categories to the extent possible.

It is particularly important for projects to address the structural issues that lead to modern slavery. Projects should be encouraged to consider how to move beyond a focus on individuals and communities affected by modern slavery to engage with category IV stakeholders, including government counterparts and other powerbrokers. This has been done in the most impactful projects.

-

The authors were Sasha Jesperson and Saskia Marsh, Deployable Civilian Experts with HMG’s Stabilisation Unit, with specialist expertise in modern slavery and behavioural change interventions. ↩

-

Adapted by Saskia Marsh from methodologies used by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. See Julian Brett, Kristina Bro Eriksen, Anne Kirstine, Rønn Sørensen, Evaluation Study: Lessons learned from Danish and other international efforts on Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) in development contexts (2015), adding in modern slavery specific elements based on Sasha Jesperson and Michael Jones’ 2016 report for DfID on Modern Slavery in Sudan. ↩