National Child Measurement Programme: operational guidance 2024

Updated 1 October 2024

Applies to England

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Information on the National Child Measurement Programme

The National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) was established in 2006 and involves measuring the height and weight of reception and year 6 children at state-funded schools, including academies, in England. NHS England statistics on the National Child Measurement Programme show that every year, more than one million children are measured. They also show annual participation rates are consistently high (around 95%), with over 99% of eligible schools (approximately 17,000 schools) taking part. The NCMP participation rate for 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 were affected by COVID-19 as a result of school closures and other public health measures.

The purpose of the NCMP is to provide high quality public health surveillance data on children’s weight to understand and monitor obesity prevalence and trends at national and local levels, including the impact on inequalities and child health. The NCMP helps local authorities to plan and commission services to ensure all children have the opportunity to be healthy. It also underpins the Public Health Outcomes Framework indicators on prevalence of overweight (including obesity) in children aged 4 to 5 years and 10 to 11 years.

You can read more about the available indicators on the Public Health Outcomes Framework publication collection page.

This guidance document advises local commissioners and providers of the NCMP on how the programme should be implemented. This helps to maintain the high quality of the programme and supports a cost-effective approach.

The role of local authorities

Local authorities have a statutory function to deliver the surveillance elements of the NCMP by:

- completing the height and weight measurements of children in reception and year 6

- returning all relevant data to NHS England

The NCMP collection is funded through the public health grant for local authorities. The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), in the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), has responsibility for national oversight of the programme.

NCMP data

Each year, NHS England produces a report showing the main findings from the NCMP. OHID also publishes presentations, reports, local profiles and data visualisation tools. This includes small area data at:

- middle super output area (MSOA)

- electoral ward level

- integrated care board (ICB) and sub-ICB geographies

To see a collection of what statistics we collect and publish on public health topics, visit Statistics at OHID.

You can also find a range of other resources to support the wide use of the NCMP data to inform action at all levels to improve child health and promote a healthy weight in children in appendix 1.

NCMP data shows that the prevalence of obesity in children in reception (aged 4 to 5) and year 6 (age 10 to 11) is unacceptably high. The report NCMP: changes in the prevalence of child obesity between 2019 to 2020 and 2021 to 2022 showed that the overall change in prevalence levels has also been relatively small each year, with the exception of the unprecedented rise seen in the 2020 to 2021 NCMP annual report which showed an increase of around 4.5 percentage points. The 2022 to 2023 NCMP annual report showed that the prevalence of obesity in reception children has decreased compared to 2021 to 2022 and is one of the lowest levels since 2006 to 2007. However, for year 6 children, although the prevalence has decreased it still remains higher than pre-pandemic levels in 2019 to 2020.

The data consistently shows that the number of children living with obesity doubles between reception and year 6 (from around 10% to around 20%). Additionally, year-on-year the data has shown that children living with obesity in the most deprived 10% of areas in England is more than twice that in the least deprived 10%. The decrease in the prevalence of obesity in 2022 to 2023 can be seen across children in the least and most deprived areas, however large and persistent disparities remain.

NCMP data is also used to analyse and further understand child weight tracking including obesity. The report Changes in the weight status of children between the first and final years of primary school is a longitudinal cohort analysis of NCMP data. The findings suggest that excess weight is likely to persist or worsen during primary school. It also found that children from the most deprived backgrounds and certain ethnic communities may be at higher risk of retaining or gaining an unhealthy weight.

The NCMP is widely recognised as a world-class source of public health intelligence and the high participation rates of eligible schools and children reflect the continued effort of those implementing the programme at the local level.

1.2 Maintaining the mental wellbeing of pupils in the NCMP

The importance of mental wellbeing during the NCMP

The wellbeing of children and families participating in the NCMP is a priority. We recognise that child weight and growth can be very sensitive for some children and parents. We have highlighted the importance of maintaining the mental and emotional wellbeing of children and families in all NCMP guidance and delivery resources provided to:

- the people that carry out the measurements

- schools

- local authorities

NCMP resources developed for children and families are designed to promote healthy lifestyle behaviours and not focus on weight.

Measuring children in a sensitive way

School nursing teams and NCMP delivery staff measure children in a sensitive way, in private and away from other children. The weight and height information is shared with the parent or carer in a feedback letter (see ‘Deciding whether to provide parents with children’s measurements’ for further details on feedback letters). Where local authorities provide feedback letters, no individual information is shared with the children themselves, the teachers or the school.

It is a parent’s choice if they share the information with their child. If a parent is concerned about their child’s growth, weight, body image or eating patterns, NCMP feedback letters provide national and local information to support parents and advise them on when to seek further support from a school nurse or GP.

Communicating about child weight

Parents react in different ways to receiving their child’s NCMP feedback. So, guidance is available to help school nursing teams and NCMP delivery staff have supportive conversations with parents about the NCMP and their child’s health and growth.

Resources are available for professionals to help them talk to parents about their child’s weight, including the guidance National Child Measurement Programme: conversation framework from OHID. You can also watch the video ‘Parent and practitioner’ from Newcastle University below.

Resources are also available to support parents on how to approach talking about weight with their child, including the guidance Talking to your child about weight from the University of Bath. You can also watch the video ‘Child and parent’ from Newcastle University below.

Use of supportive terminology

The term ‘very overweight’ relates to the clinical weight status ‘obese’. Although the word ‘obese’ is a clinical classification, we recognise the sensitivity and stigma around using this term. We encourage all conversations and correspondence with parents about their child’s weight status to use the more acceptable term ‘very overweight’ instead.

Research on the psychological and emotional impact of the NCMP

The psychological and emotional impact of the NCMP has been researched. Studies show there is insufficient evidence of a direct causal link that body image, self-esteem, weight-related teasing and restrictive eating behaviours change as a direct result of being measured or receiving feedback as part of the NCMP (Viner and others, 2020). More research is needed to understand the impact.

One study on the NCMP (Grimmett and others, 2008) found that most children (96%, 351 children) are indifferent or unconcerned about being weighed or measured. The small number of children (4%, 13 children) that disliked the process were mainly from year 6, children aged 10 to 11 years. This reinforces the need for sensitivity when weighing and measuring, particularly for older children.

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) funds a policy research programme that continues to commission research on this important issue.

1.3 Deciding whether to provide parents with children’s measurements

Local authorities are encouraged to provide parents with their child’s measurements. This is not a mandated component of the NCMP, but local authorities should take account of the following considerations when making this decision.

Giving parents an objective assessment of their child’s weight

Evidence shows that parents and even health and care professionals may struggle to identify if a child is overweight by sight alone. Research shows that just over half (50.7%) of parents underestimate their children’s overweight or obesity status (Lundahl and others, 2014). NCMP feedback letters give parents an objective, professional assessment of their child’s weight status based on measurement. Research on the NCMP has consistently shown that parents want to receive their child’s feedback and 87% find them helpful (Falconer and others, 2014). Dame Fiona Caldicott’s 2013 independent report Information governance in the health and care system highlighted that there is a duty of care to share information with parents that could promote and improve their child’s health.

Giving parents a choice to share their child’s measurement

Feedback communications such as letters are addressed and sent to parents, so it is a parent’s choice if they decide to share this information with their child and take any action based on the feedback given.

Research has also shown that after receiving NCMP feedback most parents (72%) reported an intention to change health-related family behaviours and just over half of parents (55%) reported positive behaviour change for their children (Park and others, 2014). Positive behaviour changes included:

- improved diet

- less screen-time

- health service use

- increased physical activity

The letters provide parents with the opportunity to seek further advice and support if they want to.

Parents’ response to NCMP feedback

Ongoing qualitative research carried out on the programme also shows the judgment and stigma some parents (and children) experience, which directly influences their emotional response to receiving feedback about their child’s weight status. The ‘weight awareness continuum’ included in the guidance NCMP: a conversation framework for talking to parents (on page 12) helps to explain the emotional journey parents encounter when receiving feedback and how recognition is necessary to lead to behaviour change. Consideration of how weight feedback is communicated is a critical factor in how parents and children respond to child weight and height measuring and feedback (Ames and others, 2020; Hawking and others, 2023; Lampe and others, 2020; Dawson and others, 2014; Suire and others, 2020).

Feedback to parents is a low-level intervention to increase parent awareness and understanding of their child’s weight, growth and health and an opportunity to offer and guide them towards seeking support. For more information on feeding back to parents, refer to section 5.6 ‘Proactive follow up’ and section 5.7 ‘Supportive conversations with parents’.

1.4 Parent feedback letter templates

To support sharing of results with parents, OHID has developed editable parent feedback letter templates in which each child’s height, weight and body mass index (BMI) centile classification (underweight, healthy weight, overweight, very overweight) can be incorporated automatically using the NCMP IT system. You can find out how a child’s BMI is calculated, including BMI centiles, on the NHS page Calculate your body mass index (BMI) for children and teenagers.

OHID makes changes to the letter every year following user feedback and consultation with academic and behavioural experts. Some local authorities adapt the letters or produce their own letters to suit local needs, and some also phone parents to discuss the results before or after the letters are sent (see chapter 5).

1.5 NCMP IT system

The NCMP IT system is managed by NHS England. It consists of an online browser-based system, plus an offline Excel spreadsheet-based tool for data entry. The system incorporates validation at the point of data entry and provides a secure environment according to NHS standards in which pupil identifiable records can be processed and stored.

The system allows:

- multiple users to be assigned locally with access to schools and pupil data based on their role in the programme

- direct entry and upload of locally collected data for reception and year 6 children measured each year

- automated calculation of information, including BMI centile and weight category

- data export for the production of the result letters to parents

- progress reporting to assist in monitoring the measurement exercise, for example schools visited, number of pupils measured, children who have been sent feedback letters

- data quality reporting to allow monitoring throughout the collection year to ensure complete and accurate data is submitted

The local authority is responsible for allowing users to access the NCMP IT system and this is controlled at local authority level. Each area assigns an NCMP lead who is responsible for assigning all the other NCMP roles within the NCMP IT system.

Further information on the NCMP IT system, including user guidance, education materials and frequently asked questions, can be found on the NHS England page NCMP IT system.

1.6 Child oral health

Oral health is also part of general health and wellbeing and contributes to the development of a healthy child as well as school readiness. Although improving, OHID’s Oral health survey of 5 year olds in 2022 in England showed that almost a quarter (23.7%) have tooth decay when they start school.

Children who are underweight, overweight and very overweight are more likely to have caries (tooth decay, also called cavities) than those of healthy weight, even when other potential influences such as deprivation are taken into account. This shows an association between children’s BMI and the prevalence and severity of caries.

For more on the evidence between dental caries and obesity in children, see the report Dental caries and obesity: their relationship in children.

Poor oral health affects not just a child’s health but also their wellbeing and that of their family. Children who have tooth decay may have:

- pain

- infections

- difficulties with eating, sleeping and socialising

- time off school for dental treatment

The most common reason for children aged 6 to 10 to be admitted to hospital is for tooth extraction. Tooth decay and obesity are likely to occur together given that excessive intake of sugar is a risk factor for both conditions.

As consumption of free sugars is a risk factor for both dental caries and obesity, interventions that reduce sugar intake have the potential to impact tooth decay and obesity.

2. Overview of NCMP deliverables

This chapter provides an overview of the important steps involved in implementing the NCMP and important delivery dates.

2.1 NCMP deliverables

Local authorities have flexibility during the school year over when they deliver the NCMP measurements, but there are certain times to be aware of as shown in ‘activity and timeline’.

A delivery summary list for local authorities is available in appendix 2.

The annual OHID resources and product updates are expected to be made available.

2.2 NCMP dates - activity and timeline

NCMP IT system

NCMP IT system is pre-loaded with a list of eligible schools for each local authority – in August before school year starts.

The academic year starts, and local areas can measure children throughout the school year - September onwards.

NHS England publishes its national report summarising the main NCMP findings from the previous school year – in November.

Local authorities are able to access their final validated data sets from the previous year’s measurements – in the autumn.

All NCMP data must be submitted to NHS England – in early August after the school year ends. The annual submission date can be viewed on the NHS England page NCMP IT system.

OHID resources and product updates

The timings of some deliverables may vary from year to year, and OHID will communicate any changes and specific dates to local authorities as appropriate. If areas wish to receive NCMP monthly update PowerPoint slides, please contact your OHID NCMP regional lead or email [email protected] for further information.

OHID resources and product updates are as follows.

Fingertips public health data tool Obesity Profile is updated with local authority and integrated care system (ICS) area data subject to submission in November.

NCMP small area level data in Fingertips tool: trend data at small area level (at MSOA and electoral ward level) update published in November.

Local authority, regional and national child obesity slide sets update published in November.

NCMP: data sharing and analysis guidance update published in the spring (subject to change).

NCMP operational guidance, information for schools and letter templates published in the summer.

NCMP school feedback letters issued to local authorities through SharePoint for onward sharing with schools subject to data submissions timing dependent on analytical priorities.

Changes in the weight status of children between the first and final years of primary school, including local authority analysis. Publication dependent on analytical priorities.

3. Planning the measurements

This chapter provides an overview of the planning that needs to take place before measuring children. It:

- identifies the local stakeholders whose assistance can help to improve the delivery of the programme

- the lawful basis for processing NCMP data

- outlining the data that needs to be collected

- the staff training and equipment required

- the information on which schools and children should be included in the programme

You can find a summary list of critical tasks to do to help you plan before measuring children in appendix 2.

3.1 NCMP and data protection regulations

All local authorities in England are required to collect information on the height and weight of reception and year 6 school children.

The data protection regulations that apply to the NCMP are the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018). The DPA 2018 is the UK’s implementation of the GDPR. You can read more information about the DPA 2018 on the GOV.UK Data protection page.

Under the GDPR, all processing of personal data must have a lawful basis. The legal foundation for the NCMP is provided in local authority regulations, which are:

- The Local Authorities (Public Health Functions and Entry to Premises by Local Healthwatch Representatives) Regulations 2013

- The Local Authority (Public Health, Health and Wellbeing Boards and Health Scrutiny) Regulations 2013

This statutory authority means that the lawful basis for processing NCMP data is provided by the articles of the GDPR covering:

- compliance with a legal obligation

- exercise of official authority

- provision of health or social care

- public interest in the area of public health

Parental consent is not the lawful basis for the processing of NCMP data.

You can find further information on the GDPR articles that provide the lawful basis for processing NCMP data in appendix 3.

You can find further information about GDPR at the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) guidance UK GDPR guidance and resources.

3.2 Securing local engagement

Successful local delivery of the NCMP is dependent on multi-disciplinary teamwork and support from partners. This includes ensuring all involved understand the purpose, benefits and outcomes of the programme. Engage with

- local authority staff

- primary care professionals

- providers

- schools

- parents

- children

3.3 Local authority colleagues

Local authority public health teams should ensure council members are familiar with the programme. The NCMP briefing for elected members answers frequently asked questions about the programme. This includes a set of case studies that show how local authorities have used the NCMP to engage further with stakeholders to help prevent and address health inequalities.

It can be helpful to engage with other local authority colleagues. Education officers may be able to assist with obtaining contacts for schools or class-list information. They or others may also be able to help to engage and raise awareness of the programme with head teachers and school staff.

Working with communications teams and children’s services may be useful to identify existing processes used to provide information to schools. Contacting these teams may also offer an opportunity to raise awareness of the programme and share good news stories, such as through:

- local authority and school social media accounts

- school websites

- local press to residents

3.4 Primary care professionals

While not a mandated component of the programme, informing staff groups in primary care about the NCMP and their role within it is important, and is allowed for under the legislation relating to the NCMP. This can be achieved by engaging with GPs, school and practice nurses, health visitors and health trainers to ensure that they:

- are aware of the programme’s details and benefits

- are informed of local prevalence and trends in child obesity

- know how to assess child BMI centiles

- are made aware of plans for sharing the measurements with parents

Alerting these professionals in advance of sharing NCMP feedback with parents is valuable so that they can be aware of children within their practice who have been measured and may be underweight, overweight or very overweight (including those with severe obesity). They will also be able to provide appropriate assessment, advice and signposting should a parent contact them.

You can use editable ‘pre-measurement letter text for primary care practitioners’ to inform these professionals about the NCMP on the NCMP: operational guidance page.

3.5 Providers

In most areas of the country, delivery of the programme is commissioned as part of the school nursing service or to other provider organisations. Making sure school nursing teams and other providers have a good understanding of the programme and their responsibilities will help with effective delivery.

School nursing teams and provider organisations play an important role in leading, co-ordinating and advocating for the programme. They may also help to influence the development of appropriate services that respond to identified need and support the implementation of effective follow-up and referral pathways.

3.6 Engaging schools

Promoting a whole school approach

There is some evidence to suggest that a ‘whole school approach’ can contribute to improvements in helping children to move towards a healthier weight (Langford and others, 2014). A whole school approach goes beyond the learning and teaching in the classroom to incorporate actions throughout the school day. This includes integrating healthy food and physical activity into the life of a school by improving:

- school food

- opportunities to be active

- health education

It also involves partnerships with families, outside agencies and the wider community to promote consistent support for children’s health and wellbeing.

Obesity and poor educational attainment

Research suggests that there may be a relationship between obesity and poor educational attainment (Caird and others, 2011; Brooks, 2014). However, this is likely to be due to a broader picture of inequalities in health and education, with disadvantaged socio-economic groups tending to have poorer health and achieve lower levels of educational attainment.

Promoting the wellbeing of pupils

The Education and Inspections Act 2006 outlines how maintained schools have a statutory duty to promote the wellbeing of pupils in carrying out their functions Ofsted’s Education inspection framework states that:

Inspectors will make a judgement on the personal development of learners by evaluating the extent to which the curriculum and the provider’s wider work support learners to develop their character – including their resilience, confidence and independence – and help them know how to keep physically and mentally healthy.

The statutory guidance for Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education and Health Education includes content on the importance of daily exercise, good nutrition and the risks associated with an inactive lifestyle, including obesity.

Getting schools involved in the NCMP

Although school involvement in the NCMP is voluntary, the benefits of participating may be maximised through schools advocating a whole school approach to promoting health and wellbeing.

Helping boards of governors and head teachers understand the benefits of the NCMP can be a positive first step in getting schools on board, for example by providing an update slot as part of teacher training or a local education conference, or through a local authority newsletter to head teachers.

Resources to support schools

Details of resources to support schools are given in appendices 4 and 5.

Curriculum linked healthy teaching resources are available for:

- head teachers

- reception and year 6 teachers

- school nursing teams

These resources help them teach pupils about leading healthier lifestyles in the years in which they are weighed and measured as part of the NCMP. The resources include ideas for whole school activities and suggestions for engaging parents. The resources are available to download from School Zone where users can subscribe to a newsletter to receive updates on new materials and campaigns. Better Health: healthier families supports families with children aged 3 to 11 to eat well, move more and keep teeth and gums healthy.

We have has published information for schools that explains:

- the purpose of the NCMP

- what schools can do to support delivery

- how schools can encourage physical activity, healthy eating and promote positive emotional health and wellbeing

We have developed text for a pre-measurement letter to head teachers to inform them and their boards of governors about the NCMP programme. This should be sent in advance of the measurements.

The information for schools and pre-measurement letter are available, alongside this operational guidance, in the NCMP operational guidance.

3.7 NCMP school feedback letter

The legislation relating to the NCMP does not make provision for an individual child’s measurements to be given directly to schools. OHID issues a school feedback letter for each school, which local authorities can distribute to head teachers. The letter provides reception and year 6 participation rates as well as average overweight and obesity prevalence from the previous 3 years. This non-identifiable school level information is intended to inform action at a whole school rather than at an individual level. For more information on using NCMP data refer to chapter 7.

3.8 Eligible schools

School types

Every state-funded primary and middle school in a local authority boundary should be included in the NCMP. Changes to the education system mean that various types of state schools exist that are all eligible for inclusion in the NCMP. The most common ones are:

- community schools, run by the local council

- foundation schools and voluntary schools

- academies, run by a governing body independent from the local council

- grammar schools run by the council, foundation body or trust (usually secondary schools so not relevant to the NCMP)

For further information on eligible school types see appendix 7.

Assigning schools to a local authority

At the start of each data collection year the NCMP IT system is pre-loaded with a list of eligible schools for each local authority. This list is updated annually based on the Department for Education (DfE) school-level January census.

A school is assigned to a local authority if it:

- submitted data in the previous collection year

- is new and no data was submitted (based on the postcode falling within the local authority boundary)

Local authorities or the NCMP provider should check at the start of the academic year that all schools are correctly allocated.

During the collection year, schools can be added or removed from this list to take account of local changes, for example where schools have closed, or new schools have opened. From the 2019 to 2020 collection year, it is no longer possible for local authorities to add duplicate schools (for example, when a school becomes an academy). The NCMP IT system only allows the addition of a new school if the old school has been deleted by requesting the DfE number in addition to the unique reference number (URN). Since DfE numbers remain the same when a school changes status, the NCMP IT system will identify and prevent duplicate schools being uploaded.

Get information about schools provides a current register of schools, including their URN and DfE numbers. Further details available from NCMP IT system user guide part 2: setting up schools list.

Special and non-state schools

Where possible, we encourage measurements in special and non-state schools. Data from these schools will be included in the national database and returned to local authorities as part of their enhanced data set. However, since established relations with these schools vary between areas they will not be included when calculating participation rates, nor will they be included in the national report. This is because the low participation rates from privately-funded and special schools mean that the data is unlikely to be representative.

For all schools that do participate, we encourage communicating the measurements to parents.

Home-schooled children

Home-schooled children are excluded from being captured on the national IT system, as NCMP covers children in state-funded schools only. Height and weight measurement and sharing of results with parents of home-schooled children is encouraged outside the NCMP where local resources allow.

3.9 Parents and children

To support the delivery of the NCMP, it is important that parents and the wider public are aware of the importance of children having a healthy weight and understand the purpose of the programme. The media, such as local newspapers and radio, can be used to help achieve this.

By engaging with parents and children in advance of delivering the programme, you can:

- ensure parents are aware that the privacy and dignity of the child will be safeguarded at all times throughout the process

- reassure parents that their child’s measurements will not be revealed to anyone else in the school

- provide an opportunity to contextualise healthy weight and growth as an integral aspect of valuing and promoting child health and wellbeing

- raise the profile of other actions at a local level to reduce childhood obesity

3.10 Maximising delivery through links with school health and nursing services

In planning the delivery of the NCMP, it is helpful to consider how participation can be maximised through positioning the programme as an integral part of the school health and nursing services provided to children in schools.

Some local authorities align the NCMP with priorities recommended in the OHID guidance Healthy child programme: health visitor and school nurse commissioning and ‘School-aged years high impact area 3: supporting healthy lifestyles’ part of the guidance collection Supporting public health: children, young people and families. This includes health assessment at school entry, preventative and screening or other activities with year 6 children.

As having good oral health is also an important aspect of a child’s overall health, an effective way to promote a healthy growth and weight and improve child dental health is to embed them in all children’s services. You can use opportunities for health promotion and a Making Every Contact Count (MECC) approach to support healthier lifestyle choices.

DHSC and NHS England guidance Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention provides dental teams and other health and care professionals with the information they need. Local authorities can also seek advice from NHS dental public health consultants. Refer to appendix 6 for more information on child oral health.

3.11 Information needed before the measurements

Class list and delivery arrangements

Regulations relating to the NCMP require local authorities to arrange with schools to measure children’s height and weight in their area. Before the measurements take place, class list details of all children in reception and year 6 eligible to participate should be obtained.

The class lists can be shared by schools with the local authority or those working on behalf of the local authority to carry out the height and weight measurements. This sharing is lawful under the UK GDPR and DPA 2018.

You can read more about class lists in the information for schools.

As consent is not the lawful basis for processing NCMP data under the UK GDPR and DPA 2018, there is no requirement for schools to obtain the consent of parents to provide class lists to school nursing teams and NCMP providers.

Required information

School nursing or NCMP delivery teams require this information for each child for the following reasons.

Height, weight, age, sex, and date of birth: to calculate weight category (also known as child body mass index).

Ethnicity and address: to monitor differences in child weight between ethnic groups, different parts of the country and different social and economic groups.

Name, date of birth and NHS number: to link the child’s measurements from reception and year 6 and to other information from health and education records held by NHS England, DHSC and DfE, where lawful to do so. This helps government to understand how and why the weight of children is changing, and how this affects children’s health and education. This includes a child’s health data relating to:

- hospital inpatient care

- hospital outpatient care

- hospital emergency care

- maternity

- mental health

- social care

- primary care

- public health

- diagnostic care

- mortality

- cancer

- diabetes

- health, lifestyle and wellbeing surveys that a child has participated in

And a child’s education data relating to:

- educational achievement

- absence

- exclusions

- special educational needs

Parent address: to send parent feedback letters. It is essential to ensure the information is up to date to avoid sending to the wrong address.

Parent contact details including email address and telephone number: if digital communication methods are being used and proactive feedback calls are planned.

It is also useful to include the weight, height and BMI data on a child’s local health record, so it can be viewed by other health and care professionals.

Accessing and requesting information

Class-list information is available from the school census every January, which is a statutory undertaking for all state-funded schools listed in appendix 7. Contact the local education officer to gain access to this information. If the information is required earlier in the academic year, it can be requested directly from schools. If an external organisation is commissioned to deliver the NCMP they will require access to personal child data, and this should be stated in the contract to comply with data protection law.

Children who have moved schools

Children who move schools may be measured more than once. The IT system allows for the child’s measurements to be included in the data set more than once and so the parent could receive more than one feedback letter. Where a child is known to have moved school, local areas may want to check if the child has previously been measured as part of the NCMP, and whether a feedback letter has already been sent to the child’s parents before sending a further letter.

When engaging with a school, it may be helpful to establish a single named contact to liaise with to agree arrangements for the delivery of the programme in the school, including a date, time and use of a room or screened-off area in which to conduct the measurements.

3.12 Providing the opportunity to parents to withdraw their child from the NCMP

Informing parents that their child is participating in the NCMP

Parental consent is not the lawful basis for the processing of NCMP data under the UK GDPR and DPA 2018. However, local authorities must take steps to ensure parents are informed that information about their child will be processed as part of the NCMP and provide parents with an opportunity to withdraw their child from participating in the programme.

Using a pre-measurement letter

We have developed an editable pre-measurement letter to parents which ensures that the information provided to parents on the processing of their children’s height and weight data helps parents know what to expect when their child participates. The letter is available in the NCMP operational guidance

The letter explains to parents how their child’s data is collected and what it will be used for. So, it is essential that it letter explains to parents whether their child’s data will be shared with a GP or health and care professional who can promote and assist the improvement of their child’s health. This should also include text that explains that a referral to a weight management service or proactive follow up may take place, if these are planned locally.

Some of the wording shown in the letter should be used as given and not edited, because it sets out the legal requirements for the programme and the intended use of the data. The necessary wording is indicated in the letter.

Not all the information about data processing needs to be included in the letter. For example, a link directing parents to further information on the local authority or NCMP provider’s webpage could be included in the letter. If you are planning to produce further information to explain data processing and the NCMP to parents, the Wellcome Trust’s understanding patient data resource How is patient data used? may provide additional useful support.

Sending the pre-measurement letter to parents

The pre-measurement letter to parents must be sent to all children eligible to take part in the NCMP. Parents must be sent this letter at least 2 weeks before the measurements are scheduled to take place. The local NCMP provider should work with individual schools to agree the approach for ensuring the letters are circulated within this time.

The names of children who have been withdrawn by their parents in each age group should be collected. The NCMP provider should also check with the school if any other requests to withdraw children from the measurements have been received following the distribution of the pre-measurement letter.

For many schools, the routine method of communication with parents is by email, and as such, it is recommended that the pre-measurement letter is sent to parents by email. This will enable parents to directly use the hyperlinks to obtain further information online about what happens to their child’s data, and to access information from the NHS website Better Health: healthier families.

Providing additional resources to parents

Local authorities can download useful resources from the DHSC campaign resource centre (you will need to sign in or register to get these resources).

When sending out pre-measurement letters, we recommend that you attach the NCMP pre-measurement leaflet and the ‘NCMP process animation’ video below. These resources include information about the programme and why it is important for children to take part. We also recommend that you attach dental health tips leaflets. There are separate leaflets for children aged 0 to 6 and for children over 6.

Where local areas choose to send hard copies of the pre-measurement letter, they can be downloaded from the campaign resource centre for local printing. To request high-resolution versions of the leaflet please contact [email protected].

The school nursing service or other NCMP provider may also choose to communicate directly with parents and year 6 pupils about the programme, to ensure that they have received sufficient information. This can be done through a school’s newsletter, website, assembly or parents evening. School nursing resources on the School Zone are designed to help with this before, during and after measurement day. They include presentation materials for parent and pupil audiences.

3.13 Staffing

It is important there is an appropriate level of staffing resource for the successful delivery of the NCMP. A registered medical practitioner, registered nurse (such as a school nurse) or registered dietitian must manage the arrangements of the programme. This includes:

- co-ordinating and training staff

- engaging with schools

- ensuring the data is submitted to NHS England on time

Although a registered medical practitioner, registered nurse or registered dietitian must oversee the programme, the measuring may be undertaken by a healthcare assistant, children’s nursery nurse or similar grade member of staff with appropriate competencies and support. A description of the roles and responsibilities of those involved in the NCMP are listed within the NCMP cost model tool. You can find this information in ‘Appendix 1: NCMP cost model tool user guide’ of the NIHR policy research programme Evaluating the NCMP.

The NCMP cost model tool has been developed to support cost-efficient delivery of the NCMP, by providing a consistent and automated format to enter costs associated with NCMP delivery. To request a copy of the tool, please contact [email protected].

The successful delivery of the NCMP depends not only on the completion of accurate measurement but also engaging with stakeholders and entering and validating data. So, staff should have a mixture of expertise and skills, including clinical knowledge, communication, administration, IT skills, and data management and analysis.

In keeping with current safeguarding legislation, all staff who measure children as part of the programme must have an enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check. You can find more information about DBS checks on the Disclosure and Barring Service website.

3.14 Staff training

Measuring and recording data

Before starting the measurements, staff should be trained on how to accurately complete the measurements and record and upload the data.

Staff using the NCMP IT system should be competent and confident in doing so. Educational resources and guidance to support use of the NCMP IT system are available on the NHS England website NCMP IT system. Staff using the offline Excel spreadsheet should be familiar with entering and saving data in an Excel spreadsheet.

Taking calls from parents and delivering proactive follow-up

Staff responsible for taking calls from parents following the sending of feedback letters, or for proactively following up children after the measurements, should be competent in their awareness and understanding of child obesity, its impact on children’s health and its management. They should also be skilled in talking to parents about a child’s weight, lifestyle and behaviour change.

Staff should be aware of all local child weight management and physical activity services available to children in their area, and pathways for referral into them. Ideally, they will be trained in motivational interviewing to maximise the opportunity to engage in an effective discussion with a parent about their child’s weight status.

NCMP: a conversation framework for talking to parents is available to support school nurses, their teams and other professionals to hold supportive conversations with a parent about their child’s NCMP feedback.

Training staff is the responsibility of the local area. We recommend local areas cover the topics outlined in this section. See also appendix 1 for additional training and development resources and guidance.

3.15 Equipment

Accurate measurements depend on correctly using good quality equipment.

Scales

You must use class 3 scales for measuring weight and they should be properly calibrated. Scales must be CE marked with the last 2 digits of the year of manufacture (for example, CE09 for a product manufactured in 2009), and be marked with a letter ‘M’ to show it is legal for this use. This will be followed by a 4-digit number identifying the body which approved the scale.

All scales should be checked annually either by recognised UK Weighing Federation members or by electro-biomedical engineering technicians using traceable weights. If the scales display weights within in-service tolerances, they should then be usable throughout the year. If not, they must be taken out of service and returned to an approved body for calibration and verification. If at any time there is reason to believe the weighing equipment may be inaccurate, it should be recalibrated and re-verified.

If using equipment with switchable readings (between metric and imperial), the switching facility should be disabled to ensure that only the metric reading is available. If the equipment cannot be converted to metric reading only, it should be replaced as a priority.

Height measures

Height should be measured with a correctly assembled stand-on height measure that shows height in centimetres and millimetres. Old and new model components of height measurement devices should not be used together as they are often not compatible. If a component breaks, the whole device should be replaced. Wall-mounted, sonic or digital height measures should not be used. Before each measuring session, height measures should be calibrated using a measure of known length, such as a metre ruler to ensure correct assembly.

Trading Standards is a local authority regulatory and consumer protection service which, as part of its statutory weights and measures functions, will provide support to check the accuracy, calibration and suitability of weighing and measuring equipment. You can find the nearest trading standards office from the Chartered Trading Standards Institute website.

Recording children’s measurements

The NCMP IT system should be used to record children’s height and weight at the time of measurement. The NCMP IT system allows data to be recorded in 3 ways:

1. Entered directly through the online browser-based system (this is the preferred option).

This requires internet access at the point of measurement. The system will allow multiple users per local authority area, so it can be used by people measuring in different schools at the same time. It allows for validation of the data at the point of measurement and if an extreme measurement is identified, it is easy to quickly re-measure the child to confirm whether the original measurement is correct.

2. Entered into the Excel spreadsheet-based tool.

Before the school visit, the spreadsheet must be pre-populated with children’s details through the online browser-based system and stored on a secure laptop. After the visit, the laptop can be taken to a location with internet access and submitted through the online browser-based system.

3. Entered onto pre-prepared, paper-based records (as a last resort).

Before the school visit, the paper-based records must be printed with pupil details through the online browser-based tool. After the visit, they can then be inputted through the online browser-based system. This approach is not recommended as it does not allow for validation of the data at the point of measurement and errors may occur in transcribing data from the paper records to the NCMP IT system.

This paper-based approach has been provided for use only in circumstances where the first 2 options are not achievable. When using paper records, errors such as an extreme measurement may only become evident when entering data onto the NCMP IT system and at this point it will be quite difficult to investigate and correct the data.

3.16 Children who should be measured

Local authorities should plan to measure all eligible children in reception and year 6 from state-funded schools. Non-state and special schools should be invited to participate where local resources allow.

However, there are special considerations for some children who are measured.

Children with Down’s syndrome

Children with Down’s syndrome should be included in the NCMP activity on measurement day as appropriate. However, data recorded for children with Down’s syndrome should not be submitted in the NCMP IT system. This is because specialist Down’s syndrome growth charts should be used to assess weight category. To request electronic growth charts, the completion of the online licence allocation questionnaire and a one-off fee (licence charges for categories 1 or 2) sent to the Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group is required. For more information about buying licenses, read about growth charts on the Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group website.

The specialist charts should be used locally, and appropriate information shared with parents. Concerns about a child’s measurements should be followed up in line with local care pathways. The local school nursing team, special educational needs team or other specialist teams may also offer additional support to the family.

Children who may have a growth disorder

The NCMP IT system flags heights and weights that are outside the expected range. While this is done mainly for data quality purposes rather than identifying a child who may have a growth disorder, it can provide an opportunity for health and care professionals to refer or follow up a child if the weight or height is outside the expected range. Concerns about a child’s measurements should be followed up in line with local care pathways.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) provides childhood and puberty close monitoring charts for boys and girls. These charts are used to monitor children with growth or nutritional problems, such as unusually short, underweight or overweight children, and are mostly used in specialist clinics and special schools. For more information about these charts please contact [email protected].

To promote an inclusive approach, any additional physical and mental health needs such as those of children with neurodevelopmental conditions and children with special education needs, should be taken into account when considering whether a child should participate, even if their parent or carer has not withdrawn them. It is important to ensure that the child is content with being measured and is given the chance not to take part if they do not want to, their decision-making capacity and any potential consequences should be considered before a child is measured. They should be reassured about confidentiality.

Where possible it may be helpful to work with schools before the measurements take place, to identify children who might be particularly sensitive about being measured, or where measurement might not be appropriate, for example children with diagnosed eating or growth disorders.

Children absent from school on measurement day

If feasible and if resources allow, local authorities and providers are encouraged to return to measure children who were absent from school on measurement days due to sickness, or any other reason. However, this may not be possible if there are workforce pressures and difficulties with balancing priorities and challenges at the local level.

3.17 Children who should not be measured

The legislation relating to NCMP says that only children able to stand on weighing scales and height measures unaided should be measured. Children who are unable to do so should not be included. They should also be excluded from the total eligible for measurement in that school and recorded as ‘unsuitable for measurement due to physical impairment’ as a reason for non-measurement.

Children withdrawn from being measured

Children who have been withdrawn from the programme by their parents and children who refuse to participate on the day should not be measured. Eligible children who have been withdrawn or refuse to participate on the day must be included in the eligible population count in the NCMP IT system.

Children outside the usual age range

The NCMP IT system will not accept information for children outside the usual age range for reception or year 6, because their date of birth will be outside the accepted range for the programme. However, local authorities may wish to still measure these children, so they do not feel excluded or singled out.

The BMI category for children outside the usual age range can be obtained on the NHS page Calculate your BMI for children and teenagers and fed back to parents in the same way as other children receiving their results. The BMI centiles and weight categories in the NCMP IT system align with those in the NHS BMI healthy weight calculator used on the NHS website.

Children with physical disabilities and special educational needs

Care should be taken to avoid stigmatising any children who are unable to participate in the programme and to deal sensitively with any children who have particular needs. Local authorities should make reasonable adjustments in the way they commission and deliver public health services to children with physical disabilities and special educational needs and should work closely with schools to plan alternative provision.

The small number of children who are unable to take part in the programme due to a disability should be offered alternative arrangements. Their parents or carers can then still benefit from receiving information and lifestyle advice, including specialist advice appropriate to the child’s circumstances. The letter to parents of children unable to be measured unaided can assist with this (this letter is available in the NCMP operational guidance).

3.18 Participation rates

To ensure the information collected provides an accurate picture of the population, local authorities should aim to achieve participation rates by eligible children of at least 90%.

3.19 Data to be collected

NHS England website NCMP IT system has detailed guidance about:

- the mandatory and supplementary data that should be collected as part of the programme

- how to access and use the NCMP IT system

- submitting data to NHS England

3.20 NCMP IT system user set up

The responsibility for finalising the data submission lies with the local authority. This includes:

- signing off data quality

- extracting all data for the local authority area

- giving NHS England permission to delete all data

So, it is expected that the NCMP lead (or ‘super user’) works within the local authority and not for the provider organisation. Further details are available from NHS England guidance NCMP IT system user guide part 1: setting up user accounts.

Children’s personal information

It is advisable to populate some of the NCMP IT system data fields before the measurements. These include every child’s:

- name

- sex

- date of birth

- home address and postcode

- ethnicity

- NHS number

Sourcing a child’s NHS number

There are several ways local authorities report obtaining a child’s NHS number for the NCMP. These include:

- primary care data management systems such as the child health information system through an NHS delivery provider

- national information sharing systems, such as NHS England’s Spine

- local IT clinical systems, such as EMIS, PARIS and System 1

An NCMP NHS number survey report summarises the learnings from local authorities. You can request a copy of this report from [email protected].

Local authorities can use NHS England’s Personal Demographics Service to help get a child’s NHS number. Visit the website Personal Demographics Service for the access form and further support.

School information on the IT system

School names and unique reference numbers are already provided within the NCMP IT system, although any amendments can be made if required, for example if schools have opened, closed or changed name. School nursing and NCMP delivery teams can request the information required to pre-populate records from local authorities, schools, or obtained from the child health information system in advance of the measurements. It should not be obtained by asking pupils or assigned during the measurement process.

Withdrawn children’s data

Before measurement day, you should update the records of all children withdrawn from the programme to ensure these children are not measured.

If the NCMP IT system data fields have already been populated and an eligible child has been withdrawn from the programme, you do not need to remove their data from the NCMP IT system. This includes their NHS number and any other details already on their record. This is because eligible children who have been withdrawn should still be included in the eligible population count. This also meets the requirements outlined in the regulations relating to the NCMP.

You can find more information about managing a child’s record in the NHS England guidance NCMP IT system user guide part 3: pupil data management.

Recording sex of child and gender identity

Sex of child at birth is the information required for calculating BMI centile and weight category as well as for NCMP data analysis. Child gender identity should not be recorded in place of sex at birth in the NCMP IT system.

If a child identifies as a different gender and a local authority or provider is keen to include this information to assist with parent feedback, they must also collect and list ‘child’s sex at birth’ in the NCMP IT system. They should also address any concerns raised by parents about including gender identity accordingly. Local authorities are encouraged to deal sensitively with children for whom this concerns. For matters relating to gender identity, please refer to DfE guidance Equality Act 2010: advice for schools.

4. Doing the measurements

This chapter sets out how to correctly undertake the weight and height measurements.

You can find a summary list of critical tasks to do when taking the measurements in appendix 2.

4.1 Setting up the room

The measurements should take place in a private room where the results are secure and cannot be seen or heard by anyone who is not directly involved in taking the measurements. In the exceptional case that a separate room is not available, a screened-off area of a classroom can be used.

School nursing teams or NCMP providers should ensure that the calibrated weighing scale is placed on a firm, level surface with the read-out display concealed from the participating child and others. They should also ensure the height measure is correctly assembled and is placed on a firm, level surface with its stabilisers resting against a vertical surface (such as a wall or door) to ensure maximum rigidity. It is good practice to confirm that the height measure is correctly assembled by checking with an item of known length, such as a metre ruler.

School nursing teams or NCMP providers should record measurements on an encrypted, password-protected laptop or tablet using the NCMP IT system, either in its online browser-based system or offline Excel spreadsheet.

4.2 Measuring height and weight

Measuring children in a sensitive way

Research has shown that children respond pragmatically and positively to being measured if the measurements are done sensitively. Privacy while being measured is important to children and parents.

School nursing teams or NCMP providers should be aware that children can be sensitive about their height, weight, or both, and should recognise that measuring children could accentuate these sensitivities, particularly for older children.

All anxieties should be appropriately addressed during the measurements and children’s privacy, dignity and cultural needs should be respected at all times. Under no circumstances should a child be coerced into taking part or be measured if their parents have withdrawn their child from the programme.

Refer to sections 3.16 and 3.17 for information on children who should be measured and children who should not be measured as well as alternative arrangements for children who are unable to take part in the programme due to disability.

Individual measurements should not be:

- disclosed to children during or after the measuring

- fed back directly to the school or teachers (see chapter 7)

- given to individual children in the form of the feedback letter or placed in school bags as there is a risk that the child could open the letter in an unsupported environment and the letter may not reach parents

- revealed to other children

If a child wishes to discuss the measurements and has any questions, the practitioner will use their expertise to discuss these with the child and family.

Any concerns about a child’s weight status or height status should be followed up with parents in line with local care pathways.

Measuring weight

When measuring a child’s weight, you should:

- ask the child to remove their shoes and coat (as they should be weighed in normal light, indoor clothing)

- ask the child to stand still with both feet in the centre of the scales and record the weight in kilograms to the first decimal place, that is the nearest 0.1kg (for example 20.6kg) using the NCMP IT system (measurements to 2 decimal places are also acceptable)

- not round measurements to the nearest whole or half kilogram

Measuring height

When measuring a child’s height, you should:

- ask the child to remove their shoes and any heavy outdoor clothing that might interfere with taking an accurate height measurement

- ask the child to stand on the height measure with their feet flat on the floor, heels together and touching the base of the vertical measuring column (the child’s arms should be relaxed, and their bottom and shoulders should touch the vertical measuring column)

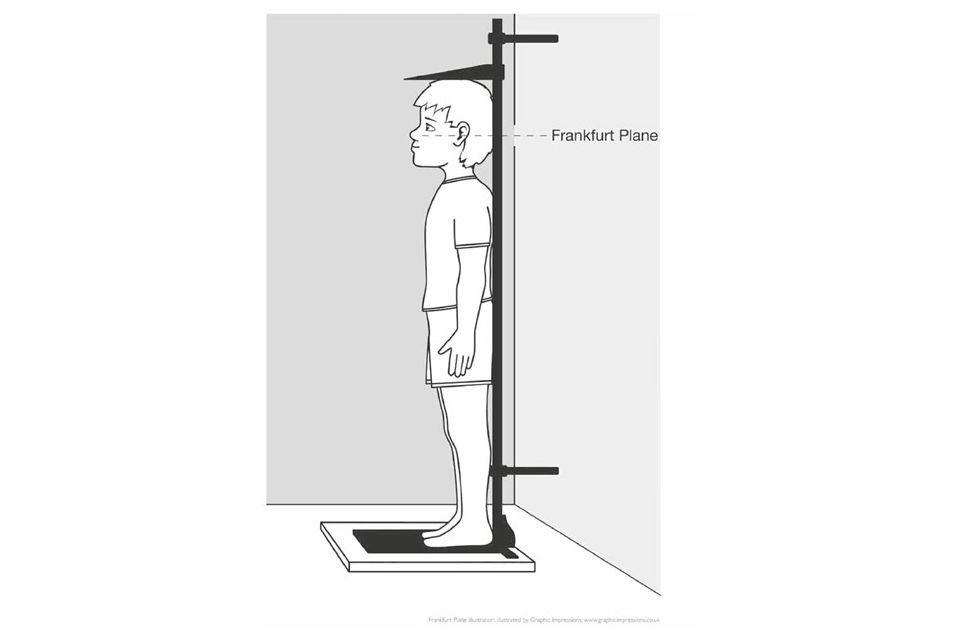

- position the child’s head so that the Frankfurt plane is horizontal (see figure 1) to obtain the most reproducible measurement, and the measuring arm of the height measure should be lowered gently but firmly onto the head, flattening the hair before the measurer positions the child’s head in the Frankfurt plane

- where appropriate, respectfully ask the child to change their hairstyle if it does not allow for an accurate measurement (but if this is not possible, record the most accurate measurement you can and make a note of the circumstances)

- ideally have one practitioner ensure that the child maintains the correct position while the other reads the measurement

- record the height in centimetres to the first decimal place, that is the nearest 0.1cm (for example 120.4cm) using the NCMP IT system

- not round measurements to the nearest whole or half centimetre

- whenever possible, repeat measurements to ensure accuracy

Figure 1: the Frankfurt plane

The figure shows a child standing on the height measure with their feet flat on the floor, heels together and touching the base of the vertical measuring column. The child’s arms are relaxed by their side, and their bottom and shoulders are touching the vertical measuring column.

A broken line drawn on the figure shows where the Frankfurt plane is. The Frankfurt plane is an imaginary horizontal line that passes through the inferior margin of the left orbit and the upper margin of the ear canal. This means that the ear hole should be aligned with the bottom of the eye socket. This position will allow the crown of the head to raise the measuring arm of the height measure to the child’s true height.

Source: Frankfurt plane illustration by Graphic Impressions

5. After the measurements: parent feedback letters and proactive follow-up

This chapter sets out how children’s measurements should be shared with parents and what proactive follow-up should be offered following the measurements.

You can find a summary list of critical tasks to do after taking the measurements in appendix 2.

5.1 Feedback of measurements to parents

While it is not a mandated component of the programme, local authorities will want to consider if and how they share information with parents that could promote and improve a child’s health. Research shows that 87% of parents find the feedback helpful, and nearly 75% reported an intention to make positive lifestyle changes following NCMP feedback (Viner and others, 2020).

Experience from parents, local NCMP teams and behavioural insights work strongly suggests that any information given to parents should be done positively and sensitively, avoiding stigmatising terms such as ‘obese’, ‘fat’ and ‘morbidly obese’. Under no circumstances should the feedback information be given directly to a child as it is a matter for the parent to decide if and how they share this information.

Assigning BMI centiles to children

The NCMP IT system uses the British 1990 child growth reference (UK90) to assign each child a BMI centile, which takes into account their height, weight, sex and age. Clinical BMI centile thresholds are used for the purposes of individual assessment to place each child in 1 of 4 weight categories. This is automatically generated in the NCMP parent feedback letter template. For more information see table 1 and the section on BMI centiles (p-score), standard deviation scores (z-score) and UK90 growth reference below.

This is the approach recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines Obesity: identification, assessment and management and Obesity prevention and the RCPCH Growth charts. Both organisations include information on follow up of children above the 91st and 98th centiles that should be considered by local areas.

Despite factors that can alter the relation between BMI and body fatness, such as fitness, ethnic origin and puberty, NICE and RCPCH recommend that BMI (adjusted for age and sex) be used as a practical estimate of adiposity (measure of fatty tissue) in children and young people. BMI remains the most accurate, practical and non-invasive method for determining body fat in children. The NCMP IT system automatically classifies children using this recommended approach.

Comparing a child’s height and weight centiles in place of calculating BMI centile, to assess whether they are overweight or very overweight is not reliable, and this method should not be used. Children should be assessed using age-specific and sex-specific BMI centiles as described above.

Waist to height ratio measurement

NICE clinical guideline ‘Obesity: identification, assessment and management’ recommends that a waist to height ratio measurement is considered alongside a child’s BMI centile in individual clinical assessments to understand the risk of any potential physical health conditions. This is because the location of where children carry weight on their bodies has an influence on their health. If a child falls into an unhealthy weight category, this will give additional health information.

BMI centiles (p-score), standard deviation scores (z-score) and UK90 growth reference

Growth patterns differ between boys and girls, so both the age and sex of a child is taken into account to calculate their BMI. So, a child’s BMI is given as a centile to show how one child compares with other children of the same age and sex.

To determine whether any individual child’s measurements should be considered too low or too high, the child’s height, weight or BMI is compared to a child growth reference. These growth references describe the expected pattern of growth for children at different ages and by sex and are usually based on a relatively healthy historic population (one with low obesity prevalence).

A child growth reference can be used to convert the height, weight or BMI measurements of individual children into standard deviation scores (z-scores) or centiles (p-scores). BMI thresholds are defined by a specific z-score, or centile, on a child growth reference. The z-scores describe whether the child has a higher or lower value for that measure than would be expected of children of the same age and sex. The p-score describes the BMI centile value, for example a BMI p-score of 0.85 means the child’s BMI is on the 85th centile.

The NCMP uses the British 1990 growth reference (UK90) for child BMI centile thresholds for population monitoring and clinical assessment in children aged 4 years and over (Cole and others, 1995). For more information refer to RCPCH resource Growth charts - information for parents and carers.

Table 1: child clinical BMI centile thresholds and classifications

The table below shows clinical BMI centile thresholds used to classify a child’s weight category. The weight categories are:

- severe obesity

- very overweight (clinical obesity)

- overweight

- healthy weight

- underweight (low BMI)

- very thin

It also shows the weight category generated automatically by the NCMP IT system for the parent feedback letter template and the corresponding BMI standard deviation (z-score), rounded BMI centile (p-score) and approximated BMI centile line on a growth chart.

The table uses symbols to refer to a score ‘less than or equal to’ (≤) and ‘greater than or equal to’ (≥).

| Weight category generated automatically in parent feedback letter template | Clinical BMI centile category [note] | BMI standard deviation (z-score) | Rounded BMI centile (p-score) | Approximated BMI centile line on growth chart |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very overweight (above expected) | Severe obesity | ≥2.6666 | ≥0.996 | ≥99.6th |

| Very overweight (above expected) | Very overweight (clinical obesity) | ≥2 | ≥0.98 | ≥98th |

| Overweight (above expected) | Overweight | ≥1.3333 | ≥0.91 | ≥91st |

| Healthy weight | Healthy weight | >-2 to <1.3333 | >0.02 to <0.91 | >2nd to <91st |

| Underweight (below expected) | Underweight (low BMI) | ≤-2 | ≤0.02 | ≤2nd |

| Underweight (below expected) | Very thin | ≤-2.6666 | ≤0.004 | ≤0.4th |

Note: defined in the RCPCH resource Body mass index (BMI) chart for boys and girls and Cole and Preece (1990) (Cole and others, 1995)

5.2 Children falling on BMI centile thresholds

BMI centile has defined thresholds for determining the results. For a small number of children, who fall right on the threshold boundary of a BMI category, rounding of BMI centiles to whole numbers may result in children with the same BMI clinical classification (z-score) being assigned to different BMI centile (p-score) classifications. For this reason, we do not recommend that BMI centile numbers (p-score) are included in the feedback letters for parents, and instead, only their weight category (see table 1) should be used (as is done automatically for the national parent feedback letter template).

You can find more information about BMI centile thresholds in the document ‘Frequently asked questions’ under the ‘Related information’ section on the NCMP IT system page.

When talking to parents whose children fall close to the thresholds of weight categories, for example the healthy weight and overweight boundary, school nursing teams or NCMP providers should consider explaining this to the parent. They should also advise that a subsequent measurement in a few months’ time may be helpful in checking whether the child is moving towards a healthier weight category. You can signpost parents to the NHS page Calculate your BMI for children and teenagers to monitor their child’s weight status.

5.3 Children identified at extreme BMI centiles

Children who fall on extreme BMI centiles, that is either on or below the 0.4th centile or on or above the 99.6th centile (see table 1) are likely to require specialist healthcare support. For this reason, we recommend that as a minimum duty of care, children who fall on extreme BMI centiles are proactively followed up to ensure they are offered appropriate support and care. Refer to section 5.6 ‘Proactive follow up’ later in this chapter.

Children identified on or above the 99.6th centile are classified as severely obese. The immediate and long term cardiovascular, metabolic and other health consequences of severe paediatric obesity are likely to require specialist treatment (Kelly and others, 2013; Ells and others, 2015; Farpour-Lambert and others, 2015).

Children on or below the 0.4th centile are classified as underweight, and this may indicate under-nutrition. They are likely to have additional health problems and should be referred for further assessment and support.

The parent feedback letter template automatically classifies all children:

- who fall on or above the 99.6th centile as ‘very overweight’

- who fall on or below the 0.4th centile as ‘underweight’

See section ‘Producing feedback letters’ below for further guidance.

Children with extreme BMI centiles will have a flag automatically added to their record in the NCMP IT system. This will allow immediate identification of children measuring at extreme BMI centiles when their data is added to the NCMP IT system. It is also possible to identify children with extreme BMI centiles by looking at the ‘BMI Centile (p-score)’ column in the combined data extract.

For further information and guidance on extreme BMI centiles in the NCMP IT system, viewing the BMI centiles (p-score) to 4 decimal places and downloading the combined data extract, refer to NHS England guidance NCMP IT system user guide part 3: pupil data management

5.4 Producing feedback letters

The NCMP IT system should be used to generate feedback letters for parents using the editable parent feedback letter template. Further details available from NCMP IT system user guide part 4: generating feedback letters.

The letters have been developed following feedback from child health and behavioural insights experts, NCMP practitioners and parents. They are editable so the content can be amended to meet the needs of local areas.

Editing template parent feedback letters or developing local letters

When editing the national template letters, or developing your own local letters, it is important to consider that parents receiving the letters may be sensitive to the information and feel their parenting skills are being criticised. So as far as possible, the letters should be non-judgemental, non-stigmatising, sensitive and positively phrased.

When producing the letters, you should include a child’s NHS number.

BMI centile categories used

While there are 6 clinical BMI centile categories outlined in table 1, NCMP data will show only 4 weight status categories. They are:

- healthy weight

- underweight

- overweight

- very overweight

However, 3 letters are automatically generated in the NCMP parent feedback letter template. They are:

- healthy weight

- underweight

- overweight and very overweight

We strongly advise these same categories are used if developing local letters.

Checking information is correct

It is the responsibility of local areas to check at least one out of every 10 letters printed against the information entered into the NCMP IT system to ensure the information has come through as expected. For example, you should check that the child’s weight, height and assigned weight status category are correct, and the correct date of birth and address are shown.

How to send feedback letters

It is best practice to post feedback letters to parents and carers, particularly for year 6 pupils, rather than giving letters to children to take home. This is to mitigate the risk of the letters getting into the hands of children’s peers, leading to comparisons of measurement data and potential bullying. Sending feedback letters by electronic means should also be considered where this meets local electronic communication and information governance guidelines as a means of achieving a paperless approach to the NCMP.

To ensure the feedback letters are meaningful, they should be sent to parents and carers as soon as possible and within 6 weeks after the measurements.

As with other health information being sent to a child’s parents, the national NCMP parent feedback letter templates are addressed to the ‘Parent/carer of [child name]’. This is because it is unlikely that the name of the parent or carer will be known, and it is at parents’ discretion as to whether they share the information with their child.

5.5 Resources and support for parents

General resources to share

A link directing parents to the Better Health: healthier families - children’s weight page is included in the parent feedback letter template, providing additional support and information relevant to a child’s weight status.