National DNA Database: biennial report, 2018 to 2020 (accessible)

Published 2 September 2020

National DNA Database Strategy Board Biennial Report

2018-2020

Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 63AB(8) of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984

September 2020

© Crown copyright 2020

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]

ISBN 978-1-5286-1916-5

CCS0420503628 09/20

Ministerial Foreword

The Government is committed to ensuring that the National DNA Database (NDNAD) and the National Fingerprint Database are instrumental in supporting policing and that they continue to be an effective tool for the police in helping to solve crimes and also to prove people’s innocence.

In 2018/19 the NDNAD provided 30,551 routine matches, including to 626 homicides and 639 rapes, and 214 urgent matches, including 46 to homicides and 59 to rapes. In 2019/20 the NDNAD provided 22,916 routine matches including 601 to homicides and 555 to rapes and 219 urgent matches, including 58 to homicides and 56 to rapes. The percentage of crime scene profiles which matched a subject profile on load to the NDNAD (referred to as the match rate) was 67% in 2018/19 and 66% in 2019/20. Although there was a decrease in the overall number of matches reported in 2019/20 compared to the previous year, there was only a small decrease in the match rate, so it continues to demonstrate the effectiveness of the NDNAD.

This report includes information on the National Fingerprint Database policing collections and the National DNA Database. Work on the Home Office Biometrics (HOB) DNA Strategic Project has continued over these 2 years covered by this report and it is now nearing completion of the first stage, which will deliver a replacement platform on which the NDNAD sits with enhanced functionality. A further stage is planned for increased international capability, creating better links with similar databases in other countries, and it is of note for the commencement in 2019/20 of Prüm international DNA exchanges between the UK and EU Member States. In addition there has also been continued and significant progress made by HOB on improving fingerprint checking and searching.

Kit Malthouse MP

Minister of State (Minister for Crime and Policing)

Chair of the Strategy Board’s Foreword

I am very pleased to present this report as Chair of the Forensic Information Databases (FIND) Strategy Board; this being my first since taking over as Chair of the Board in August 2018.

During this reporting period we have continued to align the governance and oversight of the Fingerprint and DNA databases in support of the Government’s strategy for forensic science and in providing clearer and more transparent governance.

A significant amount of work has been completed during this two year period to enable Prüm international DNA exchanges between the UK and EU Member States to commence from July 2019. The UK’s connection to Prüm DNA has produced positive results for both the UK and the EU partners connected so far. From searches of historic data held on the UK’s National DNA Database, the UK has received around 13,000 initial ‘hits’ from its Prüm DNA connections. In turn, EU Member States have received approximately 47,000 initial hits from their connections with the UK.

The Home Office Biometrics (HOB) Programme project to deliver a replacement IT system (with enhanced capability) for the National DNA Database has continued over this reporting period, with this significant development now nearing completion. There has also been extensive work carried out by HOB to enhance fingerprint matching and checking services; with this report outlining the key details for the changes and benefits.

Another significant technological development this reporting period has seen the Contamination Elimination Database (CED) project move to a business as usual service. This continues to develop with an expansion of the database including the DNA profile records of staff where there is the potential for the contamination of crime scene DNA samples through the environment within which DNA sampling occurs, or consumables used within the DNA sampling and processing.

The effectiveness of the NDNAD as an important tool for policing has continued to be demonstrated by the overall match rate, remaining at 66% in 19/20, following the loading of a crime scene profile.

Ben Snuggs

Assistant Chief Constable

NPCC Chair of the Forensic Information Databases Strategy Board

The Forensic Information Database Strategy Board

Governance and oversight of the National DNA Database[footnote 1] is provided by the Forensic Information Databases (FIND) Strategy Board, referred to in statute as the NDNAD Strategy Board. Following the publication of the government’s Forensic Science Strategy, the governance role of the Strategy Board was expanded from the NDNAD alone to cover the National Fingerprint Database, during 2016/2017 and the name was changed accordingly. Since 31st October 2013, the Board has operated on a statutory basis.[footnote 2]

The strategic aim of the Strategy Board is to provide governance and oversight for the operation of the National DNA and Fingerprint Databases:

- it must issue guidance about the destruction of DNA profiles and fingerprints retained under the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 (PoFA)[footnote 3];

- it may issue guidance about the circumstances under which applications for retention under PoFA[footnote 4] may be made to the Commissioner for the Use and Retention of Biometric Material (‘The Biometrics Commissioner’)[footnote 5] [footnote 6];

- it must publish governance rules which must be laid before Parliament[footnote 7]; and

- it must make an annual report to the Home Secretary about the exercise of its functions[footnote 8].

The statute still refers to the requirement for the ‘NDNAD Strategy Board’ to publish an annual report, so this report is titled accordingly. However, in line with the wider responsibilities described above, the report covers both the national DNA and fingerprint databases.

The governance rules[footnote 9][footnote 10] set out in more detail the way in which the Board operates, and include its objectives[footnote 11] which are to implement strategy and policy to ensure:

-

the most effective and efficient use of DNA and fingerprint databases to support the purposes laid down in the legislation (and no other), these are;

- the interests of national security;

- terrorist investigations;

- the prevention and detection of crime;

- the investigation of an offence or the conduct of a prosecution; and

- the identification of a deceased person.

-

the public is aware of the governance, capability and limitations of the NDNAD and fingerprint databases so that confidence is maintained in its use across all communities;

-

That the future use of the NDNAD and fingerprint databases takes account of developments in science and technology and delivers improvements in efficiency and effectiveness across the Criminal Justice System.

-

The most proportionate, ethical and transparent use of the NDNAD and fingerprint databases across the Criminal Justice Service.

- The most ethical and effective use of international searching of UK DNA profiles and fingerprints.

The core members of the Board are:

- a representative of the National Police Chiefs’ Council

- a representative of the Home Office;

- a representative of the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners; Additional members[footnote 12] include:

- the Chair of the Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group [footnote 13]

- the Information Commissioner (or representative);

- the Forensic Science Regulator[footnote 14] (or representative);

- the Biometrics Commissioner (or representative);

- representatives from the police and devolved administrations of Scotland and Northern Ireland; and

- such other members as may be invited.

The rules go on to specify:

- the responsibilities of the Board;

- the appointment of the Chair;

- rules around audits;

- the delegation of functions; and

- the proceedings of the Board.

They may be added to, repealed or amended with the agreement in writing of the Home Secretary.

The Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group

The Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group (BFEG)[footnote 15], which replaced the National DNA Database Ethics group in 2017, provides independent expert advice to Home Office ministers on ethical issues related to the use of biometrics, forensics, and large data sets.

The remit of the group includes consideration of the ethical impact on society, groups and individuals, of the capture, retention and use of human samples and biometric identifiers. This includes DNA and fingerprints, as well as facial recognition and other biometric identifiers.

Current work streams for the BFEG include:

- Provision of advice on Home Office projects using explainable data-driven technology such as automated categorisation of data

- Investigation of the ethical issues in the use of live facial recognition technology in collaborations between police forces and private entities

- Provision of ethical advice to the Home Office Biometrics programme and review of their Data Protection Impact Assessments

The group also provides support and advice on ethical matters to other stakeholders such as the Biometrics Commissioner and the Forensic Science Regulator.

In addition, the Chair of BFEG sits on the Forensic Information Databases Strategy Board and provides advice in areas such as:

- Policy regarding the retention of biometrics from convicted individuals;

- Governance and ethical operation of police databases containing biometric information;

- Policy on access to and use of the Forensic Information Databases and other matters relating to the management, operation and use of biometric or forensic data;

- The ethical application and operation of technologies which produce biometric and forensic data and identifiers;

- Ethical issues relating to scientific services provided to the police service and other public bodies within the criminal justice system;

- Review of applications for research involving access to biometric or forensic data;

- Review of the annual report from the FIND Strategy Board and other policy and consultation documents prepared by the Home Office.

1. The National DNA Database (NDNAD)

1.1 About NDNAD

1.1.1 Introduction

NDNAD was established in 1995. It holds electronic records of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), known as profile records, taken from individuals and crime scenes, and provides the police with matches linking an individual to a crime scene or a crime scene to another crime scene. Between April 2001 and March 2020 it produced 731,160[footnote 16] matches to unsolved crimes.

1.1.2 DNA profile records

NDNAD holds two types of DNA profile:

i. Individuals

The police can take a ‘DNA sample’ from every individual that they arrest. This consists of their entire genome (the genetic material that every individual has in each of the cells of their body) and is usually taken by swabbing the inside of the cheek to collect some cells. The sample is then sent to an accredited laboratory, known as a ‘forensic service provider’ (FSP), which looks at discrete areas of the genome (which represent only a tiny fraction of that individual’s DNA) plus the sex chromosomes (XX for women and XY for men[footnote 17]) and use these to produce a ‘subject’ profile consisting of 16 pairs of numbers (which correspond to the 16 areas analysed) and a sex marker derived from the sex chromosomes. The profile is almost unique in unrelated individuals; the chance of two unrelated people having identical profile records is less than one in a billion[footnote 18]. Aside from sex, a DNA profile does not reveal any other characteristics of the individual it is taken from such as their race or physical appearance.

An example profile would be:

X,Y; 14,19; 9.3,9.3; 12,15; 22,23; 28,30; 11,14; 19,20; 9,12; 13,15; 18,18; 15,15; 10,13; 14,16; 18,21; 15,16; 24,29

The DNA profile is loaded to NDNAD where it can be searched against DNA profile records recovered from crime scenes.

ii. Crime scenes

DNA is recovered from crime scenes by police Crime Scene Investigators (CSIs). Nearly every cell in an individual’s body contains a complete copy of their DNA so there are many ways in which an offender may leave their DNA behind at a crime scene (for example, in blood or skin cells left on clothing or surfaces) even just by touching something. CSIs examine places where the perpetrator of the crime is most likely to have left traces of their DNA behind. Items likely to contain traces of DNA are sent to an accredited laboratory for analysis. If the laboratory recovers any DNA, it will produce a crime DNA profile which can be loaded to NDNAD.

1.1.3 Matches

NDNAD searches the DNA profile records from crime scenes against the DNA profile records from individuals or other crime scenes. A full match occurs when the 16 pairs of numbers (and sex marker) representing an individual’s DNA are an exact match to those in the DNA left at the crime scene or when a crime scene profile matches another crime scene profile.

i. Full Match

The diagram below illustrates a match between a subject profile (Top row) and a crime scene profile (Bottom row).

Where a match is made, this indicates that the individual may be a suspect in the police’s investigation of the crime. It may also help to identify a witness or eliminate other people from the police investigation.

ii. Partial Match

Sometimes it is not possible to recover a complete DNA profile from the crime scene; for instance where the perpetrator has tried to remove the evidence or because it has become degraded. In these circumstances, a partial crime profile is obtained, and searched against individuals on NDNAD, producing a partial match.

The diagram below illustrates a partial match between a subject profile (Top row) and a crime scene profile (Bottom row).

Partial matches provide valuable leads for the police but, depending on how much of the information is missing, the result is likely to have lower evidential weight than a full match.

1.1.4 Familial searches

One half of an individual’s DNA profile is inherited from their father and the other half from their mother. As a result, the DNA profile records of a parent and child, or two siblings, will share a significant proportion of the 16 pairs of numbers. This means that, in cases where the police have found the perpetrator’s DNA at the crime scene, but they do not have a profile on NDNAD, a search of the database, known as a ‘familial search’, can be carried out to look for possible close relatives (parents, children, or siblings) of the perpetrator. Such a search may produce a list of possible relatives of the offender. The police use other intelligence, such as age and geography, to narrow down the list before investigating further. The search is computerised and involves only the DNA profile records on NDNAD.

Due to the cost and staffing needed to carry out familial searches, they are used only for the most serious of crimes. All such searches require the approval of the FIND Strategy Board chair or their nominee. A total of 17 familial searches were carried out in 2018/19 and a total of 16 familial searches were carried out in 2019/20.

1.1.5 Identical siblings

The inherited nature of DNA means that identical siblings will share the same DNA profile, and the DNA profiling system currently used for NDNAD purposes cannot differentiate between identical siblings. However, even identical siblings have different fingerprints so these can be used to differentiate them. Fingerprints may be taken by the police electronically from any individual that they arrest. They are then scanned into IDENT1, the national fingerprint database. Unlike DNA (where samples have to be sent to a laboratory for processing) fingerprints can be loaded instantly allowing police to verify a person’s identity at the police station, thereby ensuring that their DNA profile and arrest details are stored against the correct record.

As at 31st March 2019, 9,907 possible sets of identical twins and 14 possible sets of identical triplets have been identified on the NDNAD.

As at 31st March 2020, 10,326 possible sets of identical twins and 15 possible sets of identical triplets have been identified on the NDNAD.

1.1.6 Who runs NDNAD?

Since 1st October 2012, NDNAD has been run by the Home Office on behalf of UK police forces. 36[footnote 19] vetted Home Office staff have access to it. Police forces own the DNA profile records on the database, and receive notification of any matches, but they do not have access to it.

1.2 Who is on NDNAD?

1.2.1 Number of profile records held on and deleted from NDNAD

As at 31st March 2019, NDNAD held 6,387,001 subject profile records and 624,907 crime scene profile records. The number of subject records held on the NDNAD is shown in figure 1. In 2018/19, 258,134 new subject profile records were loaded to NDNAD, together with 38,789 new crime scene profile records. Figures 2a & 2b show the number of profile records loaded to the NDNAD per year. Table 1 shows the breakdown of crime scene records loaded in 2018/19 by offence type.

As at 31st March 2020, NDNAD held 6,568,035 subject profile records and 647,378 crime scene profile records. The number of subject records held on the NDNAD is shown in figure 1. In 2019/20, 268,892 new subject profile records were loaded to NDNAD, together with 31,569 new crime scene profile records. Figures 2a & 2b show the number of profile records loaded to the NDNAD per year. Table 2 shows the breakdown of crime scene records loaded in 2019/20 by offence type.

Some individuals have more than one profile on NDNAD. This can occur where the force chooses to load another record or where they are sampled twice under different names. Approximately 14.7%[footnote 20] of the profile records on NDNAD are duplicates of an individual already sampled. Allowing for these duplicates, the estimated number of individuals on NDNAD as at 31st March 2020 was 5,604,185 (as at 31/03/19 14.0% of records were estimated to be duplicates and the estimated number of individuals was 5,491,832)

In 2018/19 117,430 subject profile records were deleted from NDNAD (including 188 under the ‘Deletion of Records from National Police Systems guidance (‘the Record Deletion Guidance’); see ‘3.3 Early Deletion’). Additionally, 4,846 crime scene profile records were deleted.

In 2019/20 124,492 subject profile records were deleted from NDNAD (including 280 under the ‘Deletion of Records from National Police Systems guidance (‘the Record Deletion Guidance’); see ‘3.3 Early Deletion’). Additionally, 7,597 crime scene profile records were deleted.

Figure 1: Number of subject profile records held on NDNAD (in millions) (2010/11 to 2019/20)[footnote 21] [footnote 22]

| Month | Number (in millions) |

|---|---|

| March 2011 | 6.60 |

| March 2012 | 6.97 |

| March 2013 | 6.74 |

| March 2014 | 5.72 |

| March 2015 | 5.77 |

| March 2016 | 5.86 |

| March 2017 | 6.02 |

| March 2018 | 6.20 |

| March 2019 | 6.39 |

| March 2020 | 6.57 |

Figure 2a: Number of subject profile records loaded onto NDNAD per year (in thousands) (2010/11 – 2019/20) [footnote 23] [footnote 24] [footnote 25]

| Year | Number (in thousands) |

|---|---|

| 2010-11 | 474.4 |

| 2011-12 | 398.9 |

| 2012-13 | 362.4 |

| 2013-14 | 361.9 |

| 2014-15 | 311.7 |

| 2015-16 | 292.3 |

| 2016-17 | 269.5 |

| 2017-18 | 259.1 |

| 2018-19 | 258.1 |

| 2019-20 | 268.9 |

Figure 2b: Number of crime scene profile records loaded onto NDNAD per year (in thousands) (2010/11 – 2019/20) [footnote 26] [footnote 27]

| Year | Number (in thousands) |

|---|---|

| 2010-11 | 40.0 |

| 2011-12 | 38.9 |

| 2012-13 | 33.2 |

| 2013-14 | 35.0 |

| 2014-15 | 36.9 |

| 2015-16 | 39.4 |

| 2016-17 | 40.8 |

| 2017-18 | 40.1 |

| 2018-19 | 38.8 |

| 2019-20 | 31.3 |

Table 1: Number of crime scene profile records loaded by crime type (2018/19)[footnote 28] [footnote 29] [footnote 30]

| Crime type | Number of crime scene profile records loaded | Proportion of total number of crime scene profile records loaded (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 17,826 | 47% |

| Vehicle Crime | 5,842 | 15% |

| Criminal Damage | 2,062 | 5% |

| Violent Crime | 1,919 | 5% |

| Drugs | 2,185 | 6% |

| Robbery | 1,747 | 5% |

| Theft | 624 | 2% |

| Rape | 851 | 2% |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 794 | 2% |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 544 | 1% |

| Firearms | 686 | 2% |

| Other sexual offences27 | 235 | 1% |

| Arson and fire investigations | 231 | 1% |

| Fraud | 127 | 0% |

| Public Order | 140 | 0% |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 170 | 0% |

| Blackmail | 11 | 0% |

| Explosives | 6 | 0% |

| Other | 1,947 | 5% |

| Total | 37,947 | 100% |

Table 2: Number of crime scene profile records loaded by crime type (2019/20)[footnote 31] [footnote 32] [footnote 33]

| Crime type | Number of crime scene profile records loaded | Proportion of total number of crime scene profile records loaded (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 13,071 | 48% |

| Vehicle Crime | 3,701 | 13% |

| Criminal Damage | 1,397 | 5% |

| Violent Crime | 1,388 | 5% |

| Drugs | 2,019 | 7% |

| Robbery | 1,283 | 5% |

| Theft | 452 | 2% |

| Rape | 627 | 2% |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 753 | 3% |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 518 | 2% |

| Firearms | 504 | 2% |

| Other sexual offences [footnote 27] | 176 | 1% |

| Arson and fire investigations | 182 | 1% |

| Fraud | 73 | 0% |

| Public Order | 106 | 0% |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 141 | 1% |

| Blackmail | 7 | 0% |

| Explosives | 3 | 0% |

| Other | 1,078 | 4% |

| Total | 27,479 | 100% |

1.2.2 Geographical origin of subject profile records on NDNAD

NDNAD holds profile records from all UK police forces (as well as the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man) but only profile records belonging to England and Wales forces are subject to PoFA[footnote 34]. Scotland and Northern Ireland also maintain separate DNA databases; however, due to the likelihood of offenders moving between UK nations, profile records loaded to these databases are also loaded to NDNAD.

Table 3: Number of subject and crime scene profile records retained on NDNAD by nation (as at 31st March 2019)[footnote 35] [footnote 36]

| Nation | Subject profile records | Crime scene profile records | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| England[footnote 37] | 5,469,596 | 571,737 | 6,041,333 |

| Scotland | 362,850 | 18,412 | 381,262 |

| Wales | 352,638 | 25,292 | 377,930 |

| Northern Ireland | 160,137 | 6,956 | 167,093 |

| Other[footnote 38] | 41,780 | 2,510 | 44,290 |

| TOTAL | 6,387,001 | 624,907 | 7,011,908 |

Table 4: Number of subject and crime scene profile records retained on NDNAD by nation (as at 31st March 2020)[footnote 35] [footnote 36]

| Nation | Subject profile records | Crime scene profile records | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| England[footnote 37] | 5,615,953 | 592,434 | 6,208,387 |

| Scotland | 371,848 | 18,879 | 397,900 |

| Wales | 365,967 | 26,052 | 384,846 |

| Northern Ireland | 171,037 | 7,370 | 178,407 |

| Other[footnote 38] | 43,230 | 2,643 | 45,873 |

| TOTAL | 6,568,035 | 647,378 | 7,215,413 |

1.2.3 Sex, age and ethnicity of individuals on NDNAD

The subject profile records held on NDNAD all come from people who have been arrested for an offence, so the composition is different from that of the general population. For example, only half the UK population is male but the majority of DNA profile records belong to men, because the majority of those arrested are male.

Figure 3a: Proportion of subject profile records on NDNAD by sex (as at 31st March 2019)[footnote 39]

| Sex | Proportion |

|---|---|

| Male | 80.3% |

| Female | 19.1% |

| Unknown | 0.6% |

Figure 4a: Proportion of subject profile records on NDNAD by sex (as at 31st March 2020)[footnote 40] [footnote 41]

| Sex | Proportion |

|---|---|

| Male | 80.4% |

| Female | 19.1% |

| Unknown | 0.6% |

Figure 3b: Number of subject profile records on NDNAD by ethnicity, as determined by the sampling officer (as at 31st March 2019)[footnote 42] [footnote 43]

| Ethnicity | Number |

|---|---|

| White - North European | 75.5% |

| Black | 7.6% |

| Asian | 5.3% |

| White - South European | 2.2% |

| Middle Eastern | 0.8% |

| Chinese, Japanese or Southeast Asian | 0.6% |

| Unknown | 8.0% |

Figure 4b: Number of subject profile records on NDNAD by ethnicity, as determined by the sampling officer (as at 31st March 2020)[footnote 44]

| Ethnicity | Number |

|---|---|

| White - North European | 75.5% |

| Black | 7.5% |

| Asian | 5.3% |

| White - South European | 2.3% |

| Middle Eastern | 0.8% |

| Chinese, Japanese or Southeast Asian | 0.6% |

| Unknown | 8.0% |

Figure 3c: Number of subject profile records by age at time of loading onto NDNAD (as at 31st March 2019)[footnote 45] [footnote 46] [footnote 47]

| Age | Number |

|---|---|

| 10-15 | 8.0% |

| 16-17 | 6.5% |

| 18-20 | 12.9% |

| 21-24 | 13.3% |

| 25-34 | 25.1% |

| 35-44 | 18.5% |

| 45-54 | 10.2% |

| 55-64 | 4.0% |

| 65 and over | 1.4% |

Figure 4c: Number of subject profile records by age at time of loading onto NDNAD (as at 31st March 2020)[footnote 48] [footnote 49]

| Age | Number |

|---|---|

| 10-15 | 7.8% |

| 16-17 | 6.4% |

| 18-20 | 12.8% |

| 21-24 | 13.3% |

| 25-34 | 25.2% |

| 35-44 | 18.6% |

| 45-54 | 10.3% |

| 55-64 | 4.1% |

| 65 and over | 1.5% |

These data are published quarterly on NDNAD web page on www.gov.uk[footnote 50]. The age of criminal responsibility in England and Wales is 10; there were 9 profiles from children aged under 10 on NDNAD. These were all Scottish Samples which were taken from ‘Vulnerable persons’ (an individual who was believed to have the potential to come to harm and / or go missing) and were loaded with appropriate consent and authorisation for retention and searching on the NDNAD.

1.3 How many crimes does NDNAD help solve?

1.3.1 Introduction

NDNAD matches crime scene profile records against subject profile records and other crime scene profile records, providing the police with invaluable information that helps them to identify possible suspects and solve crimes (albeit that a DNA match in itself is not usually sufficient to secure a conviction so not every match will lead to a crime being solved).

1.3.2 Types of searches

i. Routine loading and searching

As described at paragraph 1.1.2, samples are usually profiled and the profile records are then loaded to NDNAD for routine searching. Routine matches made from profile records loaded to NDNAD are shown in table 5a & 6a below.

ii. Non-Routine and urgent searches

In order for a profile to be uploaded to NDNAD, it must consist of a minimum of four pairs of numbers and a sex marker (for crime scene profile records) and a full profile[footnote 51] (for subject profile records). Where this criterion is not met, for crime scene records, it is nonetheless possible to carry out a non-routine search of NDNAD. For the most serious crimes, NDNAD provides an urgent non-routine search service which is available 24 hours a day.

Matches made following non-routine searches are shown in tables 5&6 b and those made following urgent searches in tables 5&6c.

1.3.3 Match rate

i. Overall match rates

In 2018/19, the chance that a crime scene profile, once loaded onto NDNAD, matched against a subject profile stored on NDNAD was 66.94%[footnote 52]. Figure 5 shows the yearly match rate on loading a crime scene profile to the NDNAD.

In 2019/20, the chance that a crime scene profile, once loaded onto NDNAD, matched against a subject profile stored on NDNAD was 65.52%[footnote 53]. Figure 5 shows the yearly match rate on loading a crime scene profile to the NDNAD.

These do not include crime scenes that match another crime scene on loading, or where a profile was deleted in the same month as it was loaded.

Further matches will occur when a new subject profile is added to NDNAD and matches to a crime scene profile already on it. As at 31st March 2019, there were 207,891[footnote 54] crime scene profile records on NDNAD that had not yet been matched. As at 31st March 2020, there were 213,003[footnote 55] crime scene profile records on NDNAD that had not yet been matched. The crimes relating to these crime scenes might be solved if the perpetrator’s DNA was taken and added to NDNAD. Every individual who is arrested will have their DNA searched against existing crimes on NDNAD, even if their profile is subsequently deleted.

Figure 5: Match rate on loading a crime scene profile (2010/11 to 2019/20)[footnote 56]

| Year | Match rate |

|---|---|

| 2010-11 | 59% |

| 2011-12 | 61% |

| 2012-13 | 61% |

| 2013-14 | 62% |

| 2014-15 | 63% |

| 2015-16 | 63% |

| 2016-17 | 66% |

| 2017-18 | 66% |

| 2018-19 | 67% |

| 2019-20 | 66% |

ii. Number of matches[footnote 57]

In 2018/19, NDNAD produced 214 subject to crime scene matches following on from an urgent search of NDNAD, including to 46 homicides and attempted murders[footnote 58] and [footnote 59] rapes, the offence breakdown of these matches is shown in table 5c. It also produced 30,551 routine subject to crime scene matches, including to 626 homicides and 639 rapes, the offence breakdown of these routine matches is shown in table 5a. It provided 1,377 crime scene to crime scene matches (this information is useful in helping to identify serial offenders). It also provided 3,246 matches following a non- routine search. A large number of the non-routine searches will produce a partial match, although a partial match has less evidential value than a full match, it can nonetheless provide the police with useful intelligence about a crime. The offence breakdown of these non-routine searches can be seen in table 5b.

In 2019/20, NDNAD produced 219 subject to crime scene matches following on from an urgent search of NDNAD, including to 58 homicides and attempted murders59 and 56 rapes, the offence breakdown of these matches is shown in table 6c. It also produced 22,916 routine subject to crime scene matches, including to 601 homicides and 555 rapes, the offence breakdown of these routine matches is shown in table 6a. It provided 921 crime scene to crime scene matches (this information is useful in helping to identify serial offenders). It also provided 2,964 matches following a non- routine search. A large number of the non-routine searches will produce a partial match, although a partial match has less evidential value than a full match, it can nonetheless provide the police with useful intelligence about a crime. The offence breakdown of these non-routine searches can be seen in table 6b.

Table 5a: Number of routine subject to crime scene matches made by crime type (2018/19)[footnote 60] [footnote 61] [footnote 62]

| Crime | Matches |

|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 13,377 |

| Vehicle crime | 5,158 |

| Criminal damage | 1,897 |

| Violent crime | 1,756 |

| Drugs | 1,646 |

| Robbery | 1,447 |

| Theft | 557 |

| Rape | 639 |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 626 |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 522 |

| Firearms | 573 |

| Other sexual offences | 179 |

| Arson and fire investigations | 173 |

| Fraud | 85 |

| Public order | 129 |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 141 |

| Blackmail | 4 |

| Explosives | 5 |

| Other[footnote 63] | 1,637 |

| TOTAL | 30,551 |

Table 6a: Number of routine subject to crime scene matches made by crime type (2019/20)

| Crime | Matches |

|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 10,151 |

| Vehicle crime | 3,468 |

| Criminal damage | 1,377 |

| Violent crime | 1,299 |

| Drugs | 1,483 |

| Robbery | 1,103 |

| Theft | 441 |

| Rape | 555 |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 601 |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 496 |

| Firearms | 416 |

| Other sexual offences | 145 |

| Arson and fire investigations | 164 |

| Fraud | 71 |

| Public order | 84 |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 107 |

| Blackmail | 5 |

| Explosives | 3 |

| Other[footnote 64] | 947 |

| TOTAL | 22,916 |

Table 5b: Number of non-routine search matches made by crime type (2018/19)[footnote 65]

| Crime | Searches | Matches | Matches (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 1,854 | 1,000 | 54% |

| Vehicle crime | 567 | 385 | 68% |

| Criminal damage | 78 | 60 | 77% |

| Violent crime | 230 | 154 | 67% |

| Drugs | 375 | 261 | 70% |

| Robbery | 384 | 222 | 58% |

| Theft | 66 | 46 | 70% |

| Rape | 392 | 215 | 55% |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 210 | 102 | 49% |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 37 | 29 | 78% |

| Firearms | 207 | 139 | 67% |

| Other sexual offences | 109 | 49 | 45% |

| Arson and fire investigations | 37 | 22 | 59% |

| Fraud | 28 | 17 | 61% |

| Public Order | 11 | 8 | 73% |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 40 | 22 | 55% |

| Blackmail | 5 | 1 | 20% |

| Explosives | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Other[footnote 66] | 1,895 | 514 | 27% |

| TOTAL | 6,526 | 3,246 | 50% |

Table 6b: Number of non-routine search matches made by crime type (2019/20)

| Crime | Searches | Matches | Matches (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 1,660 | 900 | 54% |

| Vehicle crime | 366 | 250 | 68% |

| Criminal damage | 50 | 26 | 52% |

| Violent crime | 210 | 125 | 60% |

| Drugs | 406 | 290 | 71% |

| Robbery | 361 | 224 | 62% |

| Theft | 56 | 35 | 63% |

| Rape | 233 | 114 | 49% |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 200 | 100 | 50% |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 44 | 27 | 61% |

| Firearms | 263 | 163 | 62% |

| Other sexual offences | 104 | 53 | 51% |

| Arson and fire investigations | 37 | 21 | 57% |

| Fraud | 12 | 4 | 33% |

| Public Order | 8 | 6 | 75% |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 42 | 22 | 52% |

| Blackmail | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Explosives | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Other[footnote 67] | 2,321 | 604 | 26% |

| TOTAL | 6,374 | 2,964 | 47% |

Table 5c: Number of urgent non-routine search matches by crime type (2018/19)[footnote 68]

| Crime | Searches | Matches | Matches (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 22 | 16 | 73% |

| Vehicle Crime | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Criminal Damage | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Violent Crime | 18 | 11 | 61% |

| Drugs | 13 | 9 | 69% |

| Robbery | 14 | 9 | 64% |

| Theft | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Rape | 119 | 59 | 50% |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 74 | 46 | 62% |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Firearms | 22 | 15 | 68% |

| Other sexual offences | 33 | 19 | 58% |

| Arson and fire investigations | 4 | 3 | 75% |

| Fraud | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Public Order | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 8 | 4 | 50% |

| Blackmail | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Explosives | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Other[footnote 69] | 54 | 23 | 43% |

| TOTAL | 382 | 214 | 56% |

Table 6c: Number of urgent non-routine search matches by crime type (2019/20)[footnote 70]

| Crime | Searches | Matches | Matches (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burglary (including aggravated) | 20 | 15 | 75% |

| Vehicle Crime | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Criminal Damage | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Violent Crime | 20 | 14 | 70% |

| Drugs | 9 | 6 | 67% |

| Robbery | 23 | 16 | 70% |

| Theft | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Rape | 98 | 56 | 57% |

| Homicide (including attempted) and manslaughter | 97 | 58 | 60% |

| Traffic (including fatal) | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Firearms | 22 | 15 | 68% |

| Other sexual offences | 21 | 12 | 57% |

| Arson and fire investigations | 3 | 2 | 67% |

| Fraud | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Public Order | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Abduction and kidnapping | 4 | 3 | 75% |

| Blackmail | 5 | 3 | 60% |

| Explosives | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Other[footnote 71] | 37 | 17 | 46% |

| TOTAL | 363 | 219 | 60% |

1.3.4 Outcomes

The number of offenders convicted with the help of DNA evidence is not recorded. However, DNA evidence is instrumental[footnote 72] in the conviction of the perpetrators of many serious crimes. For example:-

1. West Yorkshire Police ‘Cold Case’ Murder of Amy Shepherd

86 year old Amy Shepherd was found dead in her ground floor flat in Wibsey, Bradford in August 1994. Raymond Kay, aged 70 was identified as part of a ‘Cold Case Review’ carried out by West Yorkshire Police, which involved the application of new, specialist forensic techniques on exhibits seized as part of the original enquiry 25 years earlier. Raymond Kay’s name was first put forward as a result of a DNA match on the National DNA Database when a small hair recovered from Amy’s neck was subjected to very sensitive DNA profiling. Raymond Kay was given a mandatory life sentence and will serve a minimum of 17 years before he can be considered for release.

2. Murder of Jill Hibberd - South Yorkshire Police

The body of 73 year old Jill Hibberd was found in the living room of her home in Barnsley, South Yorkshire, on the 31st May 2018, having been brutally attacked. She was found by neighbours, concealed behind the sofa; a post mortem revealed that she had died as a result of sustaining in excess of 68 stab wounds. Following targeted cellular recovery from Jill’s body and fast-track DNA analysis, a match to Lee Fuelop was released by the National DNA Database within 48 hours of Jill’s body being discovered. Lee Fuelop then became the focus of the enquiry and several other persons of interest were exonerated. 40 year old Lee Fuelop was found guilty at Sheffield Crown Court and given a mandatory life sentence.

3. West Yorkshire Police Rape

In the early hours of the 1st September 2018, a 67 year old woman was subjected to a terrifying sexual assault by an unknown intruder who forced entry into the assisted- living retirement complex where she lived. The victim managed to fight off her attacker, and thought she had scratched his face during the struggle. A male matching the description given by the victim was arrested a few streets away and remanded into custody. The victim’s nail scrapings were fast-tracked and a male DNA profile was derived which did not match the suspect. This unknown profile was immediately searched against the National DNA Database, and a name was returned. The male was located, arrested and his clothing recovered; he was found to have cuts/marks to his face consistent with being scratched. This demonstrates the power of the National DNA Database in both exonerating innocent individuals at an early stage in serious crime investigations, and identifying potential suspects quickly, to allow further forensic evidence to be secured. The male was found guilty and sentenced to a minimum of 12 years in prison.

1.4 Missing and Vulnerable Persons Databases

NDNAD holds DNA profile records generated from DNA samples taken from arrested individuals and crime scenes. Previously, it also held profile records relating to missing persons, and from individuals at risk of harm, for the purposes of identifying a body should one be found. In order to separate DNA profile records for individuals who have been arrested, from records for missing people and vulnerable people (which are given with consent), there are now separate databases for missing and vulnerable persons.

1.4.1 Missing Persons DNA Database (MPDD)

The MPDD holds DNA profile records obtained from the belongings of people who have gone missing or from their close relatives (who will have similar DNA). If an unidentified body is found that matches the description of a missing person, DNA can be taken from the body and compared to the relevant record on the MPDD to see if there is a match. This assists with police investigations and helps to bring closure for the family of the missing person. Profile records on the MPDD are not held on NDNAD.

As at 31st March 2019, there were 1,759 records on the MPDD. In 2018/19, the MPDD produced 36 matches[footnote 73].

As at 31st March 2020, there were 1,879 records on the MPDD. In 2019/20, the MPDD produced 22 matches[footnote 74].

1.4.2 MPDD Cases

Below are some examples of cases involving the MPDD.

Case 1

On the 13th April 2018, a dog walker discovered the body of a deceased male. The man was of muscular build and wearing a fleece and dark trousers but had no other distinguishing features from which to identify him. A DNA profile was taken by the police force and checked against the MPDD. A match was obtained instantly to a low risk missing man who had been reported missing three weeks previously. It is believed he had committed suicide. Obtaining such a quick and DNA match allowed family and friends to be notified promptly and support provided by the police force.

Case 2

In February 2018, a local resident was walking along the shoreline in Dorset and discovered a human skull. Carbon dating work performed on the skull informed Police that the individual died after 1957 and he was male in gender. The DNA was uploaded to the MPDD in May 2018 and a match was obtained with a man who was reported missing in December 2012 by his crew mate. He had been travelling towards Poole in a small boat when it was hit by a freak wave and sadly he had not been seen since. As the skull was the only remains located, there were no other means of identifying this man other than through DNA.

Case 3

In November 2018, partial skeletal remains were found in woodland in Gloucestershire by National Trust workers. There was a ligature hanging from the tree above where the remains were found which implied the gentleman had committed suicide by hanging. The clothing recovered and the geographical location of this incident supported Police’s theory that these were the remains of a high risk missing man who was reported missing in June 2009 by his family. The MPDD team checked the DNA from the remains against the MPDD and a match was obtained to the missing man. Despite the time elapsed since he was reported missing, his family had not given up hope that he might return home. The DNA match gave valuable closure to the family who were then able to bury his remains.

Case 4

In April 2019, the body of a male was found on a stretch of beach in the Isle of Man. It was thought the body had been in the sea for approximately one week and was aged between 60 and 100 years of age. DNA was taken from the body and uploaded to the MPDD in May 2019. A match was immediately identified with a man who had been reported missing from Cumbria in late March 2019. The missing man had mental health issues and it was believed he may have committed suicide. It is thought that he entered the water in Whitehaven Cumbria and his body had travelled across the water to the Isle of Man.

Case 5

In late December 2019, a badly decomposed body was found in the Manchester ship canal. Gender and cause of death could not be established. DNA was taken and uploaded to the MPDD. The DNA proved to be a match to a previously found leg which had been found near to this area previously. The leg had been identified as belonging to a high risk female who was reported missing in December 2017 and in locating and identifying the rest of her remains, much needed closure to family was able to be provided. They could also reconcile her remains at her burial site.

1.4.3 Vulnerable Persons DNA Database (VPDD)

The VPDD holds the DNA profile records of people who are at risk (or who consider themselves at risk) of harm (for instance due to child sexual exploitation or honour based assault) and have asked for their profile to be added. If the person subsequently goes missing, their profile can be checked against NDNAD to see if they match to any biological material (such as blood or an unidentified body found at a crime scene) helping the police to investigate their disappearance. Profile records on the VPDD are not held on NDNAD.

As at 31st March 2019, there were 5,177 records on the VPDD, as at 31st March 2020, there were 5,656 records on the VPDD. In 2018/19 and 2019/20, there were no requests to compare records held on the VPDD with records held on NDNAD.

1. 5Technology and business process developments on the NDNAD in 2018-2020

NDNAD is constantly being adapted to incorporate new developments in technology. This involves significant work in developing and testing these changes to ensure they meet the necessary standards. The Home Office also responds to any developments that could impact on its effectiveness.

1.5.1 Home Office Biometrics Programme

The Home Office Biometrics Programme (HOB) is a programme in the Government Major Projects Portfolio. HOB is delivering biometrics matching and identification services for the UK. HOB’s focus is on three biometric modes: fingerprints, DNA and facial matching. These services enable the capture, authentication, verification, and searching and matching of individuals’ biometrics and forensics for the purposes of solving crime, protecting the border, and preventing terrorism.

The HOB Strategic DNA Project is focused on delivering a replacement (with enhanced capability) IT platform for the current NDNAD, and developing international connectivity to create better links with similar databases in other countries. To make it easier to deliver, the new platform will be delivered in stages.

1.5.2 Contamination Elimination Database

The Police Elimination Database (PED) contains DNA profile records taken from police officers and staff known as “elimination profile records”. Where a police force suspects that a crime scene sample may have been contaminated with DNA from a police officer, or a member of police staff, they can request that a direct comparison is made of DNA obtained from the crime scene against the Police Elimination profile. Each incident must be reported separately; FINDS (DNA) are not permitted to carry out full searches of the PED. In February 2018 changes were made to cease loading new records to the PED.

FINDS (DNA) is leading a project in developing a Contamination Elimination Database (CED). The Forensic Science Regulator recommended that a contamination elimination database be established to identify any contamination events on the NDNAD[footnote 75]; this allows FINDS (DNA) to carry out regular, national, searches of crime stain profile records against elimination profile records enabling easier identification of DNA profile records that are due to contamination[footnote 76].

On load to the CED, a check is made for matches against all newly submitted crime scene profile records added to the NDNAD. Following any necessary quality assurance checks by the FSP which processed the crime scene DNA sample, matches are investigated by police forces and any crime scene DNA profile records shown to originate from contamination by, for example, police officers or staff (rather than from the crime scene from which the DNA samples were obtained) are then deleted from NDNAD. As at 9th April 2020, 2,404 contamination events had been identified for investigation. Forces have been investigating these matches and 1,632 have been concluded. This has resulted in the removal of 1,432 unsolved crime stains from the NDNAD[footnote 77]. As Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) conclude their investigations the number of crime stain records deleted from the NDNAD will increase.

DNA profile records taken from serving police officers and special constables are able to be retained for elimination purposes for up to 12 months after they leave a police force (except where they transfer to another force)[footnote 78]. In line with the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), DNA samples will be destroyed within 6 months of the sample being taken.

From July 2018, the aforementioned standard retention, search, and reporting aspects have been integrated into the FINDS ‘business as usual’ activities. During 2018-20, project activities have continued with expansion of the CED to include the DNA profile records of staff where there is potential for contamination of crime scene DNA samples through the environment within which DNA sampling occurs, or consumables used within the DNA sampling and processing - there is now representation on the CED for manufacturers of products used in the DNA process, with a pilot taking place to consider Sexual Assault Referral Centre staff and Emergency Services personnel inclusion.

1.5.3 DNA mixture profile differentiation on the NDNAD

A NDNAD change was implemented on the 1st March 2018 which made it clearer to police when a clear, complete, major profile from a DNA mixed profile has been matched. The instructions tell police forces to contact the FSP for further clarification for all other DNA mixed profiles.

FINDS are now leading on further work to see if these instructions can be applied to more complicated mixed profiles.

1.6 Security and Quality Control

1.6.1 Access to NDNAD

Day-to-day operation of NDNAD is the responsibility of FINDS (DNA). Data held on NDNAD are kept securely and the laboratories that provide DNA profile records to NDNAD are subject to regular assessment.

FINDS (DNA) is responsible for ensuring that operational activity meets the standards for quality and integrity established by the NDNAD Strategy Board. 36 vetted staff have access to the NDNAD, this is made up of 29 with day to day operational access and 7 with system administrator access[footnote 79]. No police officer or police force has direct access to the data held on NDNAD but they are informed of any matches it produces. Similarly, forensic service providers who undertake DNA profiling under contract to the police service, and submit the resulting crime scene and subject profile records for loading, do not have direct access to NDNAD.

1.6.2 Compliance to international quality standards

The Forensic Science Regulator’s Codes of Practice and Conduct (version 5) states that the NDNAD is to be certificated to the IT standard, TickITplus, that its operation should be certificated to the management standard ISO 9001 and its proficiency testing scheme to the technical standard ISO 17043. The Strategy Board has been informed that the hosting and maintenance of the IT systems do not currently hold the required certification to TickITplus, however FINDS does hold certification to ISO 9001 and accreditation to ISO 17043.

1.6.3 Error rates

Police forces and FSPs have put in place a number of safeguards to minimise the occurrence of errors in the sampling and processing of DNA samples and the interpretation of generated DNA profiles; FINDS (DNA) carry out daily integrity checks for the DNA profile records loaded to the NDNAD. Despite these safeguards, errors do sometimes occur for samples taken from individuals and from crime scenes. The Contamination Elimination Database, which contains the profile records of police officers and staff and people in the wider DNA process, helps to reduce errors by highlighting DNA profiles that are potentially sourced from contamination. FINDS (DNA) continues to lead a project to incorporate the profile records of other professionals who might have come into contact with crime scene DNA (see paragraph 1.5.2).

There are four types of errors which may occur; these are explained below:

i. Force sample or record handling error:

This occurs where the DNA profile is associated with the wrong information, the source of the error in these cases could be either a physical DNA sample swap in the custody suite or the DNA record being attached to the incorrect Police National Computer (PNC) record. For example, if person A and person B are sampled at the same time, and the samples are put in the wrong bags with incorrect forms, person A’s sample would be attached to information (PNC ID number, name etc.) about person B, and vice versa. Similarly, crime scene sample A could have information associated with it which relates to crime scene sample B and vice versa. These are all errors which have occurred during police force process.

ii. Forensic service provider sample or record handling error:

As above, this occurs where the DNA profile is associated with the wrong information during forensic service provider process. Sources of this error include samples being mixed up as described above, or contaminating DNA being introduced during processing.

iii. Forensic service provider interpretation error:

This occurs where the forensic service provider has made an error during the analysis/interpretation of the DNA profile.

iv. FINDS (DNA) transcription or amendment error:

This occurs where FINDS (DNA) has introduced inaccurate information to the record on the NDNAD.

Tables 7 and 8 overleaf shows the error rate for subject and crime scene profile records held on NDNAD for each organisation. No known miscarriage of justice arose from these errors; they were detected by the routine integrity checks in place. However, had they remained undetected, they could have affected the integrity of the NDNAD.

Table 7: Error rates 2018/2019

| Organisation | Error types | Sample Type | April to June 2018 | July to September 2018 | October to December 2018 | January to March 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile records loaded | Subject | 65,741 | 66,216 | 61,039 | 65,138 | |

| Profile records loaded | Crime scene | 10,098 | 9,137 | 9,479 | 10,075 | |

| Police Forces | Sample or record handling | Subject | 43 | 51 | 46 | 49 |

| Police Forces | Sample or record handling | Subject (%) | 0.065% | 0.077% | 0.075% | 0.075% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Subject | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Subject (%) | 0.002% | 0.000% | 0.000% | 0.005% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Crime scene | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Crime scene (%) | 0.008% | 0.009% | 0.005% | 0.005% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation[footnote 80] | Subject | 7 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation[footnote 80] | Subject (%) | 0.011% | 0.000% | 0.002% | 0.009% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation[footnote 80] | Crime scene | 20 | 28 | 15 | 21 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation[footnote 80] | Crime scene (%) | 0.198% | 0.306% | 0.158% | 0.208% |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Subject | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Subject (%) | 0.000% | 0.000% | 0.005% | 0.000% |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Crime scene | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Crime scene (%) | 0.000% | 0.000% | 0.011% | 0.000% |

Table 8: Error rates 2019/2020

| Organisation | Error types | Sample Type | April to June 2019 | July to September 2019 | October to December 2019 | January to March 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile records loaded | Subject | 56,267 | 72,841 | 71,315 | 68,469 | |

| Profile records loaded | Crime scene | 7,318 | 8,305 | 8,044 | 7,632 | |

| Police Forces | Sample or record handling | Subject | 51 | 25 | 38 | 32 |

| Police Forces | Sample or record handling | Subject (%) | 0.091% | 0.034% | 0.053% | 0.047% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Subject | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Subject (%) | 0.002% | 0.000% | 0.003% | 0.000% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Crime scene | 1 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Sample or record handling | Crime scene (%) | 0.002% | 0.005% | 0.004% | 0.092% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation [footnote 81] | Subject | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation [footnote 81] | Subject (%) | 0.002% | 0.003% | 0.001% | 0.010% |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation [footnote 81] | Crime scene | 17 | 16 | 9 | 16 |

| Forensic Service Providers | Interpretation [footnote 81] | Crime scene (%) | 0.232% | 0.193% | 0.112% | 0.210% |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Subject | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Subject (%) | 0.000% | 0.000% | 0.000% | 0.000% |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Crime scene | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FINDS (DNA) | Transcription or amendment | Crime scene (%) | 0.014% | 0.000% | 0.000% | 0.000% |

1.6.4 FSP accreditation

Any FSP carrying out DNA profiling work for loading to NDNAD must be approved by FINDS (DNA) and the FIND Strategy Board and must hold accreditation to ISO17025 as defined in the Forensic Science Regulator’s Codes of Practice and Conduct. This involves regular monitoring of standards. As at 31st March 2019, 15 laboratories were authorised to load profile records to NDNAD from standard processing. There were two new laboratories accredited to load profiles to the NDNAD which commenced loading in 18/19. In addition to the 15 laboratories which were authorised to load profiles from standard processing there were also 4 sites which were authorised to load profiles to the NDNAD which were generated via a new process for a pilot project.

There were no new laboratories accredited to load to the NDNAD during 19/20 and the 4 sites authorised to load profiles to the NDNAD which were generated via the new process were removed from scope due to the pilot study finishing. Therefore as at 31st March 2020 the number of laboratories which were authorised to load profile records to NDNAD from standard processing remained at 15.

1.6.5 Forensic Science Regulator

In 2008, an independent Regulator[footnote 82] was established to set and monitor standards for organisations carrying out scientific analysis for use in the criminal justice system. The current Regulator is Dr Gillian Tully.

The required standards are published in the Regulator’s Codes of Practice and Conduct[footnote 83] and include accreditation of FSPs and FINDS to international standards.

1.7 Finance 2018 - 2020

In 2018/19, the Home Office and policing spent £1.80m[footnote 84] running NDNAD on behalf of the criminal justice system.

In 2019/20, the Home Office and policing spent £2.03m[footnote 85] running NDNAD on behalf of the criminal justice system.

2. National Fingerprint Database

2.1 Introduction

The National Fingerprint Database and National Automated Fingerprint Identification System (NAFIS), now collectively referred to as IDENT1, was established in 1999 and holds fingerprint images obtained from persons and crime scenes by Law enforcement agencies of the United Kingdom. It provides the ability to electronically store and search fingerprint images to manage person identity and compare fingerprints from individuals with fingermarks from unsolved crimes.

2.1.1 Fingerprint records

The skin surface found on the underside of the fingers, palms of the hands and soles of the feet is different to skin on any other part of the body. It is made up of a series of lines known as ridges and furrows and this is called friction ridge detail.

The ridges and furrows are created during foetal development in the womb and even in identical siblings (twins, triplets) the friction ridge development is different for each sibling. It is generally accepted that sufficient friction ridge detail is unique to each individual, although this cannot be definitively proved.

Friction ridge detail persists throughout the life of the individual without change, unless affected by an injury causing permanent damage to the regenerative layer of the skin (dermis) for example, a scar. The high degree of variability between individuals coupled with the persistence of the friction ridge detail throughout life allows for the confirmation of identity and provides a basis for fingerprint comparison as evidence.[footnote 86]

The national fingerprint database holds two types of fingerprint record:

i. Individuals.

UK Law Enforcement Agencies routinely take a set of fingerprints from all persons they arrest.

Fingerprints are usually obtained electronically on a fingerprint scanning device but are occasionally obtained by applying a black ink to the friction ridge skin and an impression recorded on a paper fingerprint form.

A set of fingerprints is known as a Tenprint and comprises:

- Impressions of the fingertips taken by rolling each finger from edge to edge.

- An impression of all 4 fingers taken simultaneously for each hand and both thumbs

- Impressions of the ridge detail present on both palms.

ii. Crime scenes

Sweat pores located along the ridges of friction ridge skin constantly exude sweat which is transferred onto surfaces when friction ridge skin comes into contact with an object. This contact leaves an invisible impression of the friction ridge detail on the surface known as a latent finger mark (or palm or barefoot print). Police Crime Scene Investigators (CSIs) examine surfaces which the perpetrator of the crime is most likely to have touched and use a range of techniques to develop latent fingermarks to make them visible. Fingermarks developed and recovered from crime scenes are searched against the Tenprints obtained from arrested persons to identify who touched the surface the fingermarks were recovered from. Latent marks can also be developed by subjecting items potentially touched by the perpetrator (exhibits) through a series of chemical processes in an accredited laboratory by sufficiently trained and competent laboratory staff.

2.1.2 Fingerprint Matches

i. Fingerprint Examination

The purpose of fingerprint examination is to compare two areas of friction ridge detail to determine whether they were made by the same person or not.[footnote 87]

The comparison process is subjective in nature and the declared outcomes are based on the knowledge, training and experience of the fingerprint practitioner. The qualified practitioner gives an opinion based on their observations, it is not a statement of fact, nor is it dependent upon the number of matching ridge characteristics.[footnote 88]

A process of analysis, comparison and evaluation is undertaken by the fingerprint practitioner, known as ACE this is followed by an independent verification process (ACE-V). The process is described sequentially, but fingerprint practitioners will often go back and repeat parts of the process in order to reach their conclusion.

There are four possible outcomes that will be reported from a fingerprint examination: Insufficient, Identified, Excluded or Inconclusive.[footnote 89]

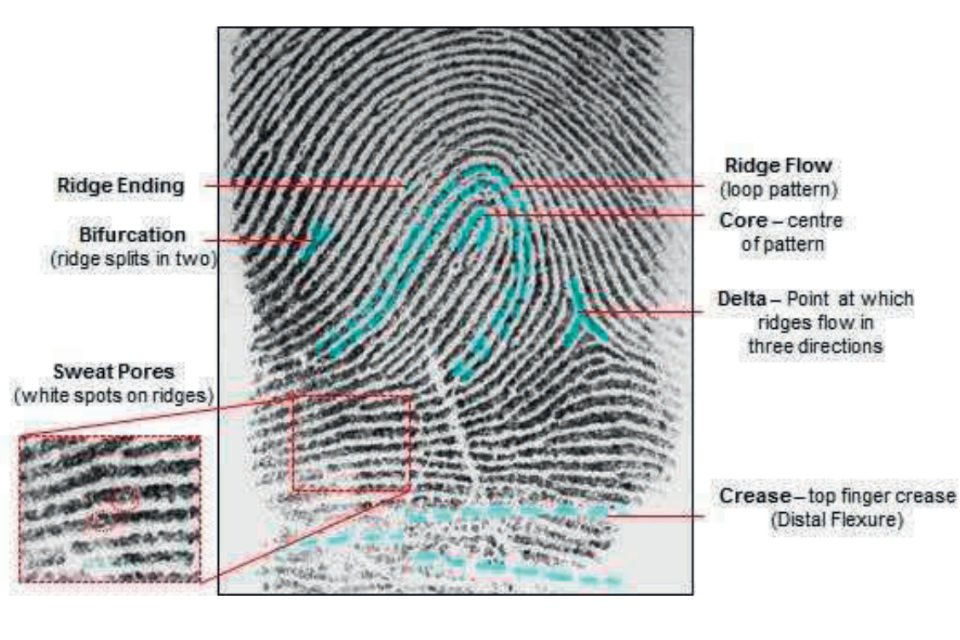

Image courtesy of Lisa J Hall, Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Services; permission to reproduce granted.

Figure 5: Friction ridge detail observable at the top of a finger. The black lines are the ridges and the white spaces are the furrows. The ridges flow to form shapes or patterns. This is an example of a loop pattern exiting to the left. There are natural deviations within the ridge flow known as characteristics such as ridge endings or forks/bifurcation. There are white spots along the tops of the ridges known as pores and there are other features present for example creases, which are normally observed as white lines.

a) Analysis

The practitioner establishes the quality and quantity of detail visible within the mark to determine its suitability for further examination by looking at ridge flow and the way ridges form shapes or patterns and how the ridges naturally deviate from their ridge paths to form characteristics such as ridge endings or forks/bifurcations. The practitioner takes into account a number of variables, for example, the surface on which the mark was left, any apparent distortion, etc.

b) Comparison

The practitioner will systematically compare two areas of friction ridge detail, for example in a print or mark with that of a print. This process consists of a side-by-side comparison to determine whether there is agreement or disagreement based upon features, in particular the sequence of ridge characteristics and spatial relationships within the tolerances of clarity and distortion. The practitioner will establish an opinion as to the level of agreement or disagreement between the sequences of ridge characteristics and features visible in both.

c) Evaluation

The practitioner will review all of their previous observations and come to a final opinion and conclusion about the outcome of the examination process undertaken.

The outcomes determined from the examination will be one of the following:

Identified to an individual: A practitioner term used to describe the mark as being attributed to a particular individual. There is sufficient quality and quantity of ridge flow, ridge characteristics and / or detail in agreement with no unexplainable differences that in the opinion of the practitioner two areas of friction ridge detail were made by the same person.

Excluded for an individual: There are sufficient features in disagreement to conclude that two areas of friction ridge detail did not originate from the same person.

Inconclusive: The practitioner determines that the level of agreement and / or disagreement is such that, it is not possible to conclude that the areas of friction ridge detail originated from the same donor, or exclude that particular individual as a source for the unknown friction ridge detail. The outcome may be inconclusive for a number of reasons; those reasons are documented in the practitioner’s report.

Insufficient: The ridge flow and / or ridge characteristics revealed in the area of friction ridge detail are of such low quantity and/or poor quality that a reliable comparison cannot be made. The area of ridge detail contains insufficient clarity of ridges and characteristics or has been severely compromised by extraneous forces (superimposition, movement etc) to render the detail present as unreliable and not suitable to proffer any other decision.

Verification

Is the process to demonstrate whether the same outcome is obtained by another qualified practitioner or practitioners who conduct an independent analysis, comparison and evaluation, therefore verifying the original outcome.

2.1.4 Outcomes using Fingerprints.

The number of offenders convicted with the help of Fingerprint evidence is not recorded. However here are some examples of cases using fingerprint evidence:-

Case 1:

In July 2019 an 18-year-old man caused criminal damage to his grandfather’s house. As the victim wanted to pursue a complaint, the offender – who had no criminal record at the time – was voluntarily interviewed. A postal charge was sent out and the man appeared at court where he pleaded guilty. He was given a suspended sentence and told to pay his grandfather £1,800 in compensation. Fingerprints were taken from the offender and checked against the IDENT1 database, generating a match to a stolen vehicle from an aggravated burglary a month after the criminal damage offence took place.

Case 2:

Three drug dealers jailed for more than 26 years after conspiring to sell tens of thousands of pounds worth of Class A drugs. Fingerprints recovered from the scene of a multi-million pound drug seizure helped unearth the true scale of their illegal activities.

Case 3:

An 18 year old was investigated for an incident of theft in November 2019. At the time there were no fingerprints for the individual on the IDENT1 database, as part of the investigation fingerprints were taken and checked against the IDENT1 database. His fingerprints were matched to previously unidentified finger-marks recovered from crime scenes relating to a murder investigation, Class A drugs supply and a traffic offence.

Case 4:

A man who raped and strangled a 27-year-old woman has been jailed for life with a key piece of evidence being fingerprints. The victim’s body was found in a burning flat in April 2019, with a bottle of a substance used as an accelerant found at the scene featuring fingerprints. Upon search of the fingerprints recovered from the crime scene against the IDENT1 database, there was a match to the offender, which acted as evidence towards his subsequent conviction for the offences.

2.1.4 Who runs the National Fingerprint Database?

Since 2012 the National Fingerprint Database has been operated by the Home Office. Law enforcement agencies have direct access to the system and they own the data they enrol within it.

The Home Office is responsible for assuring the quality and integrity of policing data held on the National Fingerprint Database (IDENT1) and other Forensic Information Databases as described in the FIND Strategy Board rules. To discharge this function on the National Fingerprint Database, FINDS - National Fingerprint and PNC Office identify and correct data errors and unexpected results on the National Fingerprint Database. The activities of the agencies that provide the inputs to the fingerprint database and its supply chain are monitored by FINDS and included in the FINDS performance monitoring framework and data assurance strategy during 2019-2020. The data assurance strategy aims to identify any errors and to ensure continuous improvement, in line with the requirements of the international standard ISO/IEC 17025[footnote 90] and the FSR’s Codes of Practice and Conduct.

2.1.5 Access to National Fingerprint database

The number of IDENT1 active users is 927. Fingerprints are captured electronically on a device called Livescan and electronically transmitted to the fingerprint database for search and the number of active Livescan accounts is 2,800 as at 27/04/2020

The FIND Strategy Board has been considering the legality and governance of a non-law enforcement agency accessing the policing collections held within IDENT1 in order to perform their national security responsibilities. This has been reported separately in the 2019 Biometrics Commissioners Report, paragraphs 96-101.

2.2 Who is on IDENT1?

2.2.1 Number of profile records held on IDENT1 System [footnote 91]

As at 31st March 2019, IDENT1 held 25,477,499 fingerprint forms relating to 8,240,881 individuals. Figure 6 shows the yearly number of individuals on IDENT 1. Figure 6 shows the yearly number of individuals retained on IDENT 1.

As at 31st March 2019, IDENT1 held 2,240,580 unidentified crime scene marks. Figure 8 shows the yearly number of unique unidentified mark submissions held on IDENT 1.

As at 31st March 2020, IDENT1 held 26,298,205 fingerprint forms relating to 8,397,761 individuals. Figure 6 shows the yearly number of individuals on IDENT 1. Figure 6 shows the yearly number of individuals retained on IDENT 1.

As at 31st March 2020, IDENT1 held 2,203,279 unidentified crime scene marks. Figure 8 shows the yearly number of unique unidentified mark submissions held on IDENT 1.

Table 9. Records held on IDENT 1

| Month End and Year | Number of Individuals on IDENT1 | Number of Fingerprint Identification Forms held on IDENT 1 | Number of unidentified crime scene marks held on IDENT1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 2011 | 8,471,960 | 19,906,978 | 1,896,885 |

| March 2012 | 8,759,820 | 21,303,201 | 1,971,938 |

| March 2013 | 9,006,957 | 22,508,260 | 2,029,028 |

| March 2014 | 7,578,717 | 21,702,050 | 2,110,962 |

| March 2015 | 7,695,129 | 22,571,529 | 2,303,565 |

| March 2016 | 7,814,041 | 23,364,390 | 2,318,576 |

| March 2017 | 7,905,419 | 24,059,907 | 2,285,669 |

| March 2018 | 8,012,521 | 24,822,939 | 2,259,139 |

| March 2019 | 8,240,881 | 25,477,499 | 2,240,580 |

| March 2020 | 8,397,761 | 26,298,205 | 2,203,279 |

Figure 6: Number of individuals on IDENT 1 (in millions) (March 2011 to March 2020) [footnote 92] [footnote 93]

| Month | Number (in millions) |

|---|---|

| March 2011 | 8.47 |

| March 2012 | 8.76 |

| March 2013 | 9.01 |

| March 2014 | 7.58 |

| March 2015 | 7.70 |

| March 2016 | 7.81 |

| March 2017 | 7.91 |

| March 2018 | 8.00 |

| March 2019 | 8.24 |

| March 2020 | 8.40 |

Figure 7: Number of Fingerprint Forms Held for all Subjects on IDENT1 (in millions) (March 2011 to March 2020) [footnote 94]

| Month | Number (in millions) |

|---|---|

| March 2011 | 19.91 |

| March 2012 | 21.30 |

| March 2013 | 22.51 |

| March 2014 | 21.70 |

| March 2015 | 22.57 |

| March 2016 | 23.36 |

| March 2017 | 24.06 |

| March 2018 | 24.82 |

| March 2019 | 25.48 |

| March 2020 | 26.30 |

Figure 8: Number of unique unidentified mark submissions held on IDENT 1 (in millions) (March 2010 to March 2019) [footnote 95]

| Month | Number (in millions) |

|---|---|

| March 2011 | 1.90 |

| March 2012 | 1.97 |

| March 2013 | 2.03 |

| March 2014 | 2.11 |

| March 2015 | 2.30 |

| March 2016 | 2.32 |

| March 2017 | 2.29 |

| March 2018 | 2.26 |

| March 2019 | 2.24 |

| March 2020 | 2.20 |

2.3 Vulnerable persons

The National Fingerprint Database contains fingerprints obtained with consent from vulnerable persons, specifically those defined at risk of honour based assault, forced marriage or female genital mutilation. The taking of fingerprints and DNA samples is a key protective measure advised by the NPCC guidance to practitioners. This is a two-fold measure, aimed at addressing identification issues in potential investigations and to protect potential victims from serious acts of violence, abduction and homicide.[footnote 96] Fingerprints donated by vulnerable persons are stored on the national fingerprint database and as such provide means to identify a vulnerable person when they come to police notice.

There were 6,386[footnote 97] sets of fingerprints relating to vulnerable people held on the database as at 31st March 2019.

There were 7,156[footnote 98] sets of fingerprints relating to vulnerable people held on the database as at 31st March 2020.

2.4 Missing persons

Fingerprints relating to unidentified bodies, and unidentified or missing persons investigations are searched on the National Fingerprint Database in an attempt to establish identity or locate a missing person. Where the investigation allows the fingerprints obtained are stored in the Missing Persons Fingerprint Collection and as such are only searchable by request. Fingerprints obtained from the belongings of a missing person are also searched against both the National Fingerprint Collection and the Missing Persons Fingerprint Collection to assist with police investigations and to help to bring closure for the family of the missing person.

There were 102 print sets relating to missing persons held on the database as at 31st March 2019. There were four Fingerprint identifications for Missing Persons Unit (MPU) cases during 18/19

There were 199 print sets relating to missing persons held on the database as at 31st March 2020. There were 5 Fingerprint identifications for MPU cases during 19/20

Case 1.

This case relates to an individual who went missing from Derby in 1991. He told family he was going away for two weeks in April 1991 and had not been seen since. He took few clothes or belongings with him. In August/ September 2018, a male deceased body was found in a house in Ireland. A passport was found at the address, which indicated who the person might be. In September 2018, an Interpol request from Interpol Dublin was received with the fingerprints of the unidentified male body and a scanned copy of a passport found on his person. A direct comparison was made between these prints and the prints stored for the individual on IDENT1 and it established that they were a match. Family were consequently notified.

Case 2.