Report: Qualitative research with working people exploring decisions about work and care

Published 7 October 2024

Crown copyright 2024.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit the National Archives.

or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

or email [email protected]

This document/publication is also available on GOV.UK

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email [email protected]

First published October 2024

Report number 92

ISBN 978-1-78659-676-5

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report presents findings from qualitative research with working people who were making, or had made, decisions about work and care. This project explored:

- their experiences;

- the decisions people faced and their information needs;

- the extent to which these needs were met by information available online.

Research design

Two strands of primary research were conducted.

The first strand consisted of 15 depth interviews and 10 follow-up interviews with working people who had learnt within the past year that a family member would need support, or increased levels of support.

In the second strand, four focus groups were conducted with people who had been providing care for a family member for one year or more. All were in work when they first started to provide care. Participants were recruited via four local carers centres, through which they were receiving support or information at the time of the focus groups.

Together, these two strands provided a combination of real-time and retrospective views and experiences. This report presents findings from both strands.

Experiences of providing care

While each participant’s experience of providing care was unique, a pattern or journey involving a number of common stages emerged:

The caring journey

The experience within each stage:

- Identification of need – Learning that a family member would need support.

- Initiation of care – A focus on the present and meeting immediate needs as opposed to planning for the long term. Providing care was reported to be mentally and physically tiring, leading participants to focus on getting through each day or week.

- Managing – Combining work and care and feeling that this was sustainable.

- Stress – Feeling pressure as a result of combining work and care. This was either because of an increase in intensity of care requirements or the length of time over which they had been providing support. Participants described that providing care over a longer period of time became more tiring and hard to manage.

- Crisis – Feeling unable to combine work and care sustainably.

- Receiving support – Gaining access to support for themselves. This tended to be a reactive measure following the preceding stages, rather than a proactive step. Support could help them to overcome feelings of isolation and social exclusion and encouraged them to consider their own wellbeing, including the role of work in their wellbeing and the potential for returning to the labour market.

Initiation of caring activities

Participants did not actively decide to initiate caring activities. Instead they instinctively reacted to learning that their family member needed support.

At this point, participants’ primary concern was meeting the needs of the care recipient. Secondary consideration was sometimes given to how to combine work and care, the financial implications of the person’s care needs or options for external support. Participants rarely considered their own wellbeing or the longer term implications of their actions at this point. When care needs emerged or increased rapidly, participants had to make decisions about care, work, finances and use of external support quickly. In these circumstances, participants reported that family members recognised that help was needed and offered support. In contrast, when care needs increased more progressively, decisions were made more slowly and this seemed to act as a barrier to receiving support from both external information sources and family members.

Regardless, their actions did have long term consequences which were not always anticipated or considered. This provides some support for the hypothesis that improved access to and use of information may improve decisions in the early stages of providing care and improve peoples’ long-term outcomes.

Although starting to provide care was not seen as an active decision, participants did discuss a number of themes that influenced whether they took up the role, and in what way. These included:

- Family circumstances – for example, whether the recipient of care was a parent or partner, and whether or not participants had siblings who were able to provide care

- Proximity – family members who lived nearer to the care recipient reported they took on day to day caring activities, rather than those who lived further away as this seemed a more practical decision at the time

I feel frustrated. Because she lives close to me, I’m the default carer, seven days a week. There wasn’t a proper discussion about sharing the load – Male, 52, Nottingham

- Perceived duty – participants often felt it was their role as a family member to provide support.

- Focusing on the present – a focus on care recipients’ current needs rather than considering what their care needs may be in a few years’ time and what this might mean for the individual providing care.

I’ve just been putting out each fire as it lights up. I haven’t had time to think that far into the future about help – Female, 54, Nottingham.

- Perceptions of external or ‘formal’ care – lack of awareness of or willingness to use professional care services affected whether or not participants took on care activities themselves.

How participants felt about combining work and care in the early stages of providing care

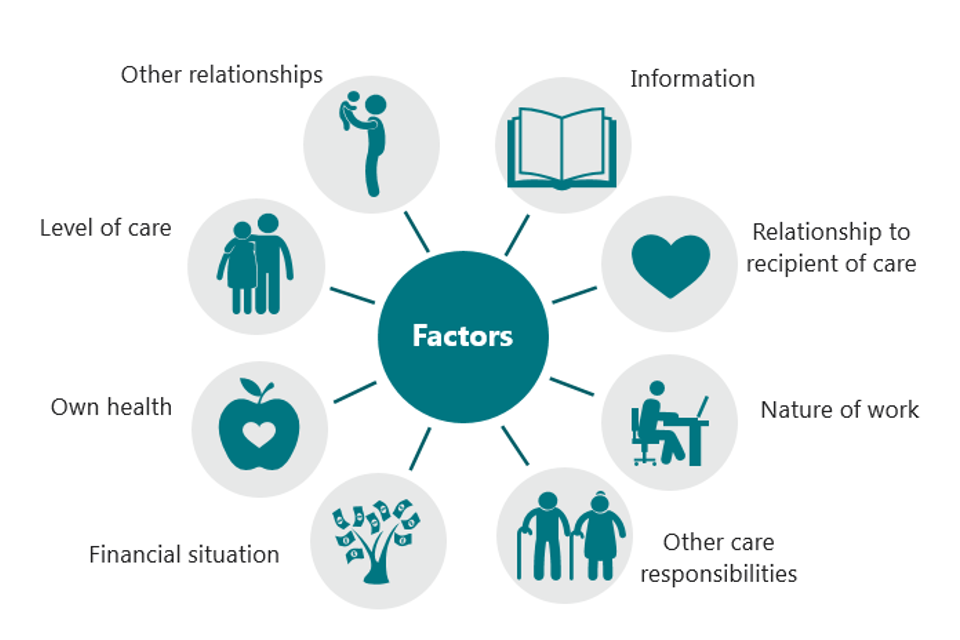

A range of themes were reported as affecting how participants felt about combining work and care. These are shown below:

Themes which affected how participants felt about combining work and care

Themes included:

- Information – Participants who had left work could feel that they had no choice but to do so. Participants could then also reflect on whether they might have stayed in employment with more information about financial support, practical support such as the availability of professional care, and the potential long term consequences of leaving work. Early information about employment rights such as flexible working was reported as being key to helping people to combine work and care

- Relationship to care recipient – the type of relationship the participant had with the person needing care (that is whether they were a parent, child or spouse of that person) affected how they felt about meeting their care needs, now and in the future

- Nature of work – whether participants’ jobs were full or part-time; whether they were self-employed or an employee; access to flexible working; how supportive their workplace was and job satisfaction all affected views on the feasibility of combining work and care. Lack of flexibility limited participants’ ability to accommodate short notice care needs or crises. Self-employment was said to bring advantages and disadvantages as it often allowed more flexible working but sole responsibility for generating income also added greater pressure

- Financial circumstances – participants with savings or a higher income were more able to reduce their working hours if needed. However, financial security was also found to act as a barrier to seeking support which could result in people ending up in a worse financial situation than they might otherwise have been

- Own health – participants who had, or whilst caring developed, mental and/or physical health conditions found being able to combine work and care more challenging

- Level of care and other caring responsibilities – the nature, intensity and unpredictability of care activities all influenced the extent to which participants felt able to combine them with work. Providing care for multiple people or living closer to the recipient of care were associated with spending more time providing care overall and so reducing participants’ capability to continue working

- Other family relationships – participants felt they were ‘spreading themselves too thinly’ by trying to combine work and care, they described feeling stressed and anxious about not having enough time for other family members (such us partners or children) as a result

Experiences of people who had been providing care for a year or more

Participants who had been providing care for longer than a year had either:

- continued with the same working pattern including number of hours

- changed their working patterns by either reducing their hours, becoming part-time or moving to more flexible shift work

- changed their employment

- left employment to provide care full-time

Flexibility at work, employer attitudes and the intensity of caring activities were felt to have strongly influenced which of these options participants took. Those who continued to work the same number of hours said that they did so in part because they could not afford not to, or that sharing of activities among their family or someone else better enabled them to combine work and care.

Those who had left the labour market demonstrated enthusiasm to return and wanted to find a way of combining work with their caring activities. They recognised the positive effect that work could have on their wellbeing.

You don’t realise how important work is [until you leave]. If you’re at work, even for just a few hours, it can boost your self-esteem….and it’s part of who you are – Female, North West Focus Group.

Experiences of accessing information and support

Initial information seeking was focussed on the health condition of the care recipient and finding support available to them. Participants rarely searched for information about support for themselves, or how best to combine work and care, unless pointed towards online sources by other people.

Offline information sources were discussed as being most helpful early on, as participants’ questions at this point were broad. Offline sources that participants wanted to use in the early stages of their caring journey included health professionals, family and friends, local charities and support groups. They thought these offline sources could be used to direct them to online information.

I can remember so many of the conversations [with the GP] were about my mother’s condition. Looking back, there wasn’t nearly enough focus on who was going to be providing the care for her – Female, 50, Nottingham.

Online information searches were used to look for answers to specific questions. Sources which were cited as being particularly helpful included condition-specific charity sites, financial advice sites and social media sites. Participants wanted online sources to be trustworthy, easy to navigate, concise and up-to-date, with a warm tone.

You get a bit overwhelmed sometimes looking [online]. It’s a wall of black text and your brain is tired after work. You want it to be short and snappy, not reading a novel – Male, 51, London.

Recognising themselves as a ‘carer’ had a strong influence on how participants looked for and used information. Until participants saw that the role they were carrying out was experienced by others and recognised by society they could feel isolated and were unaware of the support available. This is because they were unaware of what it was to be a ‘carer’ and that there was support available to this group. Recognition that the term ‘carer’ applied to them helped them look for information for themselves, led them to websites targeted at people providing care, networks of other carers providing support and it helped them identify what types of financial support they were entitled to. There was evidence of this recognition taking a number of years to happen and participants in this position said they would have wanted to understand that the term ‘carer’ applied to them earlier because of the support it unlocked. This raises the question of how information should be positioned to be accessed sooner, regardless of whether people identify as a carer or not.

You just feel like you’re a family member who is looking after someone, so at what point do you realise you’re a carer… if there was just a way of knowing that the support are there that bit earlier, to help give your life more balance – Female, North West Focus Group.

Key implications for the development of future information

The following implications for information providers emerged from the research.

Proactively supply information to support the needs of people providing unpaid care

Those in the early stages of providing care tended not to seek information to support their own wellbeing, or manage their new caring activities alongside work. To improve access to this information, it could be proactively given to people, to reduce the challenges experienced by those providing care, when navigating and accessing information independently.

Make use of offline sources to reach those providing care and signpost to further information online

Participants described more readily accessing offline sources in the early stages of providing care. Leaflets and signs in GP and hospital waiting areas were described as being particularly useful.

Target carers more explicitly through online sources in the care recipients’ journey

Participants reported accessing websites about the care recipients’ condition and needs, for example, those with a defined condition would look to condition specific charity websites or to GOV.UK for the support available for them. These websites could more explicitly reference the individual providing care and help signpost them to information about support for themselves.

Design information for time-poor users and make it easier to process

As a result of being time-poor as well as mentally and physically tired, participants preferred information to be clear, concise and easy to navigate.

Make more use of the most trusted and well known information sources

Participants did not always know what online information to trust. Some websites participants accessed early on, however, were more immediately recognised as authoritative and trusted, for example the NHS website and GOV.UK. Signposting from more well-recognised sites to other useful websites that new carers may be unfamiliar with may help them navigate and assess the legitimacy of online information more quickly.

Use a warm tone when providing information to make it more engaging

This signalled to participants that the author, or organisation, understood their experience. Participants reported they were likely to use and engage with sites which demonstrated greater understanding of their circumstances.

Emphasise the value of proactively considering their own long-term needs and options

Participants felt that they would have benefitted from being encouraged to consider their own needs as early in the journey as possible.

Note on interpretation of research findings

Findings in this report are based on research conducted in 2019. While contextual changes since 2019 may affect how people make choices about work and care and should be considered, many of the findings remain relevant to understanding the experiences of working people facing choices about work and care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the people who gave their time to participate in this research, the Carer’s Trust and the four carers centres who facilitated and hosted the focus groups.

We would also like to thank Dr Carla Groom, Cate Fisher, Lucien Bush and William Downes in the Human-Centred Design Science team, Department for Work and Pensions for their input into the design and support throughout the process.

The Authors

This report was authored by researchers at the Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute. Their roles at the time of the study in 2019 were:

Joanna Crossfield, Associate Director, Ipsos MORI

Yasmin White, Senior Research Executive, Ipsos MORI

Darragh McHenry, Research Executive, Ipsos MORI

Glossary of terms

Attendance Allowance: a benefit for individuals who are over the age of 65 and have care needs due to an illness, disability or mental health condition.

Carer’s Allowance: a benefit payment for those who spend 35 hours or more a week caring for someone who is in receipt of certain disability benefits, and who earn £151 or less per week net of allowable deductions.

Carers centres: independent, local organisations providing a range support services – usually including but not limited to information and advice – to people in the local area who are caring for someone.

Caring activities: supporting someone who needs help with everyday activities due to illness, disability or old age. This included but was not limited to supporting them with grocery shopping, laundry, dressing, cleaning and helping them with their finances or managing professional care.

Professional care: paid-for care provided by professional carers, care homes and day centres.

External support: Where the term external support is used, this refers more broadly to information and help provided both to carers themselves and/or the care recipient.

Personal Independence Payments: a benefit for people aged between 16 and 64 who have an illness, disability or mental health condition to help with some of the extra costs of their condition.

1. Introduction

This report covers findings from two strands of qualitative research. The research was conducted with people who were either currently providing unpaid or ‘informal’ care to a family member or were considering doing so. All participants were in work when they learnt that their family member would need support. Fieldwork took place in January and February 2019. These findings explore experiences of making decisions around caring and working, and information needs in this area.

1.1 Background

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), Government Equalities Office (GEO) and Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) wanted to understand how people approach decisions about meeting care needs for their relatives, combining this with work, and the extent to which the long-term consequences of these decisions are considered. The hypothesis underlying this research was that information deficits can contribute to people who provide unpaid care leaving the labour market, without understanding whether this is the best option for them long term.

The Government aims to help people providing, or considering providing, care to be more aware of the different options available to them, and the implications of the decisions they make.

The overall aim of this project was to explore:

- The experiences of working people who have decided to, or are considering, supporting a family member who needs care

- Key decisions people face and the information they need at those points

- The extent to which their information needs are met by the information available online at the time the research was conducted

The findings will be of particular interest to policy makers, charities and researchers working in this space, and indeed any organisations or professionals providing support to or coming into contact with working people facing decisions about someone else’s care.

1.2 About the research

1.2.1 Aims of this research

This research comprises two strands of primary research. The first explored the experiences of individuals who had learnt within the past year that their family member would need support. The second strand considered the experiences of those who had been providing care for over a year.

The first strand of research, depth interviews with individuals who had learnt their family member would need support or increased support in the past year sought to understand:

- How working people make decisions about how to meet a relative’s care needs, including who is involved and what questions they have

- Working people’s information needs when a family member first has care needs

- Experiences of seeking and using online information to inform decision making

- The key barriers and challenges faced when trying to find or act on information

- Preferences and views around online information tools and resources that meet their needs

The second strand of research; focus groups with people who had provided care for over one year explored:

- The experiences of those further along their caring journey, including their experiences of making decisions and seeking information about providing care

- Where they have sought information and how their information needs have changed over time

- How their employment has been impacted and what role their employer has played.

- What they would have wanted to know earlier in their journey to help them make more informed decisions

- What additional online information would help someone in a similar position to them now

1.2.2 The research design

Strand one: depth interviews with individuals who had learnt their family member would need support or increased support in the past year

Fifteen people took part in face-to-face depth interviews lasting one hour each. Prior to each interview, participants were asked to complete a short diary task. Fieldwork took place in London, York and Nottingham between the 23rd January and 1st February 2019.

Ten participants were selected to take part in 30 minute follow up telephone interviews two weeks after their first interview. The aim of these interviews was to understand if there had been any changes to their experiences and to allow both researchers and participants the opportunity to revisit topics of discussion following a period of reflection[footnote 1].

Sample

Quotas were set to ensure that all participants were currently working and had learnt within the past year that a family member would need support or an increased level of support with day-to-day activities. Participants were either considering or had taken on caring activities. This research did not include those who had decided not to take on caring activities.

Participants were recruited to reflect a range of relationships with the recipient of care; distance lived from the care recipient; their household income and IT literacy.

A full breakdown is shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Depth interviews sample[footnote 2]

| Quota | Subgroup | No. of interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Work status | Full-time | 5 |

| Work status | Part-time | 7 |

| Work status | Self employed | 3 |

| Gender | Female | 10 |

| Gender | Male | 5 |

| Age | 45-54 | 9 |

| Age | 55-63 | 6 |

| Type of condition of care recipient | Mental Health | 12 |

| Type of condition of care recipient | Physical Health | 9 |

| Type of condition of care recipient | Sensory[footnote 3] | 1 |

Strand two: focus groups with people who had been providing care for longer than one year

Four focus groups were held, one each in North West, South West, London and East Midlands. Fieldwork took place between the 14th February and 25th February 2019.

Sample

Each group consisted of between five and seven people. Every participant was in work when they learnt that their family member needed support and had been supporting this individual for over one year.

Recruitment of participants was carried out by The Carers Trust and focus groups took place in a local carers centre. This meant that all participants were receiving support through these centres.

A full breakdown of this sample is shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Focus Group samples

North West Focus Group sample

| North West | 55 to 63 | 63+ |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 3 | 2 |

| North West | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0 | 5 |

| North West | Spouse/Partner | Sibling | Child | Parent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to care recipient | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| North West | Physical Health | Mental Health |

|---|---|---|

| Care recipient condition | 3 | 4 |

| North West | Part Time | Self Employed | Caring Full Time | N/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status at time of research | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

South West Focus Group sample

| South West | Under 35 | 45 to 54 | 55 to 63 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| South West | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 4 | 3 |

| South West | Child | Parent | Daughter in Law |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to care recipient | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| South West | Physical Health | Mental Health | Sensory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care recipient condition | 6 | 6 | 1 |

| South West | PT (16-35hrs) | Self Employed | Retired | Caring Full Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status at time of research | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

London Focus Group sample

| London | 35 to 44 | 45 to 54 | 55 to 63 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| London | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 2 | 6 |

| London | Spouse/Partner | Child | Parent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to care recipient | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| London | Physical Health | Mental Health |

|---|---|---|

| Care recipient condition | 6 | 4 |

| London | PT (7-16hrs) | Caring Full Time | N/A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status at time of research | 1 | 5 | 1 |

East Midlands Focus Group sample

| East Midlands | 35 to 44 | 45 to 54 | 55 to 63 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| East Midlands | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | 6 |

| East Midlands | Spouse/Partner | Parent |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship to care recipient | 4 | 2 |

| East Midlands | Physical Health | Mental Health | Sensory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care recipient condition | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| East Midlands | Full Time | PT (16-35hrs) | Caring Full Time | Retired | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status at time of research | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

1.2.3 Conduct of the research

All fieldwork was conducted by researchers in the Employment, Welfare and Skills team at the Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute. Screening tools were used to allocate participants to quotas. With participants’ consent, interviews were recorded on 256-bit encrypted recording devices and data was handled in line with DWP and GDPR requirements. Reflecting the sensitive nature of this research, participants were offered information sheets with information of organisations they could contact for information or support if required.

1.2.4 Analytical approach

The data collected from these interviews were entered into an analysis grid in Microsoft Excel, used as the basis for analysis to identify common themes. The analysis grid grouped the findings from the interviews into themes, based around the study objectives and those which emerged through analysis. In addition, analysis considered similarities and differences amongst different subgroups such as rural and urban locations, age and gender.

1.2.5 Interpreting the findings in this report

Qualitative research is detailed and exploratory. It offers insights into people’s opinions, feelings and behaviours. All participant data presented should be treated as the opinions and views of the individuals and employers interviewed. Quotations and case studies from the qualitative research have been included to provide rich, detailed accounts, as given by participants.

Qualitative research is not intended to provide quantifiable conclusions from a statistically representative sample. Furthermore, owing to the small sample size and the purposive nature with which it was drawn, qualitative findings cannot be considered to be representative of the views of all people providing care. Instead, this research was designed to explore the breadth of views and experiences, in order to develop a greater understanding of experiences and decisions in regard to providing care and working.

Data in this report are based on self-reported perceptions and views of participants. It is important to note that although such perceptions may not always be factually accurate, and may be subject to the limits of memory, they represent participants’ beliefs and experiences as related during the time of research.

This report is based on findings from those who had taken up caring activities or were considering providing unpaid or informal support to a family member.

2. The Caring Journey

This chapter explores participants’ experiences of the caring journey. It starts by giving an overview of the journey and then focuses on the initiation of care, considerations made and how participants felt about combining work and care.

2.1 The Caring Journey

Participants reported unique caring experiences, with numerous themes influencing the shape of their overall journey. However, there was a pattern of experiences amongst participants in this sample: participants who had left the labour market reported having done so at a time when combining work and care became unsustainable[footnote 4]. This pattern is shown below[footnote 5].

- Identification of need.

- Initiation of care.

- Managing.

- Stress.

- Crisis.

- Receiving support.

The experience within each stage was:

- Identification of need – Learning that a family member would need support.

- Initiation of care – A focus on the present as opposed to planning for the long term.

- Managing – Combining work and care and feeling that this was sustainable.

- Stress – Feeling pressure as a result of combining work and care. This was either because of an increase in intensity of care requirements or the length of time over which they had been providing support. Participants described that providing care over a longer period of time became more tiring and hard to manage.

- Crisis – Feeling unable to combine both work and caring activities sustainably.

- Receiving support – Gaining access to support for themselves. This tended to be a reactive measure following the preceding stages, rather than a proactive step.

Participants in this study accessed support for themselves after recognising themselves as a ‘carer’. There were examples from the focus groups of participants not identifying as a carer until a number of years after they had initiated caring activities. Instead, they initially saw their caring activities as a progression of their relationship with their family member once they required care. Paths to identifying as a carer included:

- picking a leaflet up out of curiosity whilst in hospital with the care recipient and realising that they fitted the description of a carer

- a friend of a neighbour suggesting that a participant was a carer for her mother after seeing them together

- identification by the Jobcentre Plus when applying for benefits and realising they fit the description of a carer as given in the eligibility for Carer’s Allowance when looking for financial benefits

You just feel like you’re a family member who is looking after someone, so at what point do you realise you’re a carer… if there was just a way of knowing that the support are there that bit earlier, to help give your life more balance – Female, North West Focus Group.

Prior to seeing themselves as carers, participants were in need of support but did not know it existed for them. As such, identifying as a carer was reported as being an important part of the caring journey because it showed participants that what they were doing was recognised by society. This opened the door to accessing support for themselves and was reported to give them a sense of identity and unity with others in the same position. Evidence from the focus groups suggests that there was a lack of information aimed at those providing care through the touchpoints and information sources they were using in the course of providing care.

Case Study

One participant had been providing care for their father for the past ten years and only realised they were a carer after providing this support for five years. This realisation happened when their father was seen by a different GP – who suggested that, from what they had described about their activities, they were a carer. Until this point, the participant had explored support for their father, namely what financial support he might be entitled to, but had never looked for support for themselves. After this signposting from the GP they made contact with the local carers centre, which provided help accessing financial support and provided emotional support. It also connected them with other people providing care, helping them feel less isolated.

2.2 Initiation of caring activities

Participants in both strands of research were asked why they decided to take up caring activities to support their family member. Participants responded by clearly stating that taking on caring activities did not feel like a choice or decision. It was their instinctive reaction to the situation.

No, no, no, there was no choice to be made – it’s my mother. Period – Male, 60, London.

At this early stage, individuals were not considering potential effects on themselves, particularly in the long term. This made them less likely to seek information on support available for themselves[footnote 6].

2.2.1 Themes affecting the initiation of caring activities

Although participants emphasised that they did not experience the initiation of caring activities as an explicit choice, a number of themes emerged through discussion that seemed to have influenced their actions:

- Relationship – There were participants who reported that they took on the caring activities as a result of feeling that it was part of their role as a family member. This was the case whether the care recipient was a parent, a child or a spouse. At the initiation of caring activities, participants did not describe experiencing this ‘duty’ or ‘responsibility’ (as they referred to it) in a negative way, it was their response to meeting the needs of their family member. For example, when the care recipient was a spouse or partner, one prominent reason participants took on caring activities was because they saw themselves as the person closest to the care recipient. Participants providing care for adult children reported that this felt like part of their role as a parent

I’d expect that [to provide care], it’s no problem at all – Male, 63, York.

-

Personality – participants in this research who described themselves as having a ‘caring nature’ reported that this contributed to their uptake of caring activities, as doing so fit with their self-image

-

Family dynamics and location – The wider family dynamic influenced the adoption of caring activities, particularly when caring for parents. Participants without siblings took on the caring role for their parent as they had no other immediate family to involve. Within larger families, participants reported that the person who was seen as most able to provide support took responsibility for day to day, physical caring activities such as help with dressing, cooking, cleaning and shopping. This ability seemed to be determined by perceived amount of free time or physical proximity. Those who lived closer or had older families, for example, were more likely to provide day to day caring activities than those who lived further away or had younger children. Participants who lived further away were more likely to take on caring activities such as managing finances

-

Focusing on the present – At the initiation of caring activities, participants seemed to be focused on the present, rather than the future. This was because providing care and meeting the recipients’ needs, along with working, required their full attention, acting as a barrier to taking a long-term view

-

Professional care – Amongst participants who had not used professional care this was due to either lack of awareness or attitudinal barriers. Poor awareness of professional care, either its existence or local availability, affected likelihood of taking up caring activities as participants were unaware of other ways of meeting the care recipients’ needs. Amongst those aware of external support, attitudinal barriers included the participant and/or the person they cared for not wanting a stranger in their home or providing intimate support. This is discussed in more detail within section 2.3.1

The other thing I looked into was finding a carer…. You can find somebody that’s lovely and trustworthy, but there are some horror stories about people that could steal from them, could be nasty. You see these things on TV sometimes. That scared me. I’d rather I do it and know that he’s [father] okay – Female, 58, London.

2.3 Decision making at the start of the caring journey

Soon after their initiation of caring activities participants were thinking about work and care; financial implications for themselves and the care recipient, and use of professional care.

- Work and care – Participants considered how care and work would fit together. At the outset of providing care, participants felt able to continue in their job, however there was a need to be more flexible or take annual leave to attend doctor’s appointments and respond to other emergencies

- Financial implications – Participants reported added financial pressure from taking up caring activities. Examples included higher spending on petrol as a result of travelling more to see the care recipient and reducing working hours to accommodate care activities, resulting in lower pay

- External support to help with care needs – This support ranged from advice from doctors or other healthcare professionals, professional carers, day care centres and care homes. The severity of the recipient of care’s health condition affected the extent to which this was considered

At this point, participants reported that they gave very little consideration to their own needs and wellbeing. From the initiation of caring activities, and onwards, participants prioritised those that they were providing care for over themselves.

I’m always on the back burner… I never spend any money on myself and never look nice – Female, 49, York.

Case Study

One participant had been providing care for her daughter. As part of this she looked after her daughter’s son. In order to do so, she decreased the number of shifts she was working. This had an impact on her household finances.

Effect of the speed of progression of care needs

The extent to which participants reported considering the above themes was influenced by the speed with which the care recipient’s needs became apparent or progressed.

When the recipient of care started to need support rapidly, over a course of a day or up to one month, participants had to respond quickly. They described having to make fast decisions about providing care, work, finances and use of external support. In these circumstances, participants reported that family members recognised that help was needed and offered support.

When care recipients experienced progressive conditions, decisions around meeting care needs were made more slowly as the support required increased incrementally over time. In the early stages of providing care, participants reported feeling able to meet the recipient’s care needs, which acted as a barrier to seeking help at this point. Evidence from the focus groups with those who had been providing care for longer suggested that meeting these needs became more challenging over time, but that there was a time during which participants would have benefitted from support but were not sure how or where to access this.

Participants who experienced this gradual increase in their caring activities reported feeling that the division of caring activities in their family was imbalanced. For example, a participant whose mother moved next door to him over 15 years ago, began helping her with smaller tasks such as shopping. After she had a fall, she required a more intense level of care. This participant felt that he became the default person to provide all care because he lived so close to his mother. This led to frustration and conflict with his siblings.

I feel frustrated. Because she lives close to me, I’m the default carer, seven days a week. There wasn’t a proper discussion about sharing the load – Male, 52, Nottingham.

2.3.1 Themes affecting the use of professional care

Use of formal care[footnote 7] was affected by four themes: awareness of the support available, perceived need, attitudes towards external support, and perceived ability to meet needs.

- Lack of awareness – Participants with low awareness of external care did not know what was available, how much it would cost or whether funded care was available. These individuals felt there was not much public or prominent information about professional care and their lack of awareness acted as a barrier to seeking more information about it. As noted earlier, participants were very time-poor and did not feel they had time or energy to explore potential options

- Perceived need – Those aware of the professional care available to them described assessing their options in terms of the level of care needed and weighing this against their working hours and other responsibilities such as school runs and personal activities

- Attitudes towards professional care – Participants who expressed opposition to using professional care felt this way because they did not want a stranger to provide a family member with intimate care or feared that their family member could experience neglect or even abuse. There were also examples of participants reporting that the care recipient shared these feelings or was too ‘proud’ to accept this help. Participants felt positively towards professional care when it met their needs and enabled them to combine caring activities with work and other family commitments

She’s my wife…what are you supposed to do, put her in a care home!? – Male, East Midlands Focus Group.

My mum wouldn’t have it [professional care]…she’s too proud – Male, 60, London.

- Perceived ability to meet needs – Participants who used professional care reported that it did not consistently meet their needs, meaning they continued to provide high levels of support. For example, professional care was reported not to cover emergencies. There were also accounts of professional care being unreliable and carers not always arriving at the specified time. Participants expressed that this generated more worries or concerns than it alleviated and resulted in them checking on their family member more often. Where the care recipient had more consistent care needs or was less in need of emergency support, participants reported that professional care was better able to meet their needs

We had carers coming in when I was still working. As my mum is in a wheelchair she needed her meals bringing to her, and then the carers wouldn’t turn up or couldn’t make it on time – she has Type 2 diabetes, so she needs meals on time. You need reliable services to make it possible to work – Female, London Focus Group.

Without the carers coming in twice a day, either my wife or I wouldn’t be able to work… it allows us to keep a bit of normality about our routine – Male, 55, Nottingham.

2.4 How people felt about combining work and care in the early stages of the journey

This section is based on interviews with those in the early stages of providing care as well as retrospective views gathered in focus groups.

The themes discussed affected the intensity of participants’ caring journeys and therefore their perceptions of the sustainability of combining work and care.

Themes that influenced how participants felt about combining work and care[footnote 8]

Relationship to care recipient

Participants who cared for a parent recognised that people would need more support as they became older. However, when a partner or child needed care, participants seemed to be less emotionally prepared as it was unforeseen. They expressed concern for both their own future and that of the care recipient. The progression of care needs brought about by old age were experienced more gradually, rather than having a sudden onset. This influenced participant’s ability to combine work and care in the short and longer term.

She’s my mum, she looked after me… I was always going to look after her if something happened – Female, 52, Nottingham.

Nature of work

Nature of work was reported to strongly affect the extent to which participants felt they could sustainably combine work and care. Themes within this included:

- Working patterns – Working part-time and/or flexible hours made working and caring more manageable. Participants who worked full-time found it harder to combine caring activities and work

- Self-employment – Self-employed participants had greater flexibility than those who worked for an employer, which to an extent helped them combine caring activities and work. For example, a hairdresser arranged to see clients on set days of the week so she could see her parents on other days. However, self-employed participants were solely responsible for generating their income and felt that responding to care emergencies could jeopardise this. For example, one participant had to cancel a course she was running due to her father’s care needs. She worried that this made her unreliable, and less likely to be taken on in the future

- Flexible working – Flexible working made responding to emergencies and attending appointments with the care recipient more feasible. Flexibility could vary by sector or type of job: participants in the public sector felt their employers were open to flexible working. Participants in client-facing roles described their commitment to their clients, for example having to attend meetings at particular times meant they had less flexibility

- Work environment – Participants reported feeling that their manager and colleagues were supportive of their care activities to a point. They felt that initially there was understanding that they would need flexibility or time off to support a relative but colleagues and managers did not understand that this would be ongoing. After a certain point participants described feeling guilty about not being able to participate as fully as others at work or for needing time off

- Job satisfaction – Participants with higher job satisfaction stated that they felt work acted as a break from their caring role. Those with more experience of providing care also spoke of work as a positive channel which offered respite from caring activities as it gave them an opportunity to think about something else. In turn, work had a positive impact on wellbeing. This is explored in more detail in section 3.1.2

It [work] gives you sanity – Female, East Midlands Focus Group.

Other caring responsibilities

Providing support to more than one person influenced how participants felt about combining work and care. This was the case for both men and women. For example, one individual cared for to her mother-in-law, her neighbour, her father and mother. She reported that caring for multiple people and combining this with work and other responsibilities made her feel pulled in different directions. She felt she didn’t have time to look after herself which made her question whether she could combine all of these activities.

This [mother in law’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s] tipped us over the edge really. We knew things would never be the same. I was at my wits end trying to juggle everything she did and step up caring for her. My husband buries his head in the sand – Female, 54, York.

Financial circumstances

Those who were struggling financially or did not have savings felt this as an additional pressure. These participants looked to the Government for financial support for either the care recipient or themselves (such as Personal Independence Payments or Carers Allowance) soon after taking up caring activities.

Participants who had savings or a higher income were more comfortable about reducing their working hours to accommodate their caring responsibilities if needed, as they felt less financial pressure to keep working and maintain their standard of living.

However, there were cases in which financial security acted as a barrier to accessing support. One participant who had a well-paid job and savings and left work to care for her parents did not seek financial support for a number of years because she did not need to. This held her back her from identifying as a carer and accessing emotional support for herself, and also meant that she spent her own savings before exploring of the availability of financial support. This can be contrasted to the experiences of less financially secure participants who sought financial support sooner and through doing so, were also able to access support for themselves.

Own health

Participants reported rarely considering their own health and wellbeing. For those participants who developed mental and physical health conditions as time progressed, these added an additional challenge to feeling able to combine work and care. Early stage carers who were providing particularly intensive support quickly became aware that combining work and caring activities was physically demanding which could lead to ill-health.

You cannot think [outside of caring], it’s physically draining. You are living in a constant state of stress every day – Male, London Focus Group.

Level of care

The amount and intensity of support required by the care recipient also affected participants’ ability to work. Working and providing care was more challenging when the family member’s condition was severe and / or there were regular emergencies.

On the other hand, participants who provided non-physical support, such as managing finances, felt this to be less intensive. Working alongside these activities was reported to be more manageable.

Access to both informal and formal support can also impact on the level of care needed. For example, those who shared their caring responsibilities with someone else were better able to combine work and care.

Another factor that affected level of care activities was distance from the recipient of care. Participants who lived with the recipient of care saw their role as a full-time responsibility. In comparison, those who lived further away from their recipient of care and had limited contact did not experience this same level of intensity.

Case Study

A participant had been providing care for her mother for the past five years. In the past 12 months her mother’s care needs had intensified. In response to this, the participant started to share caring activities with her sister. To ensure that one of them is always free the participant works evening shifts, whilst her sister works during the daytime.

Other relationships

Caring activities were described as influencing relationships between participants and other family members, such as school age children and their partner. This influenced how they felt about work and care because they felt they could not meet all of their responsibilities. They felt they were ‘spreading themselves thinly’ and described feeling stressed and anxious. They felt that their family responsibilities were more important than work. This was the case for both men and women providing primary care.

Me and my husband don’t have time together [as I spend time looking for my daughter, care recipient, and her children] … there’s a lot of jealousy from my [younger] children as they get jealous of the time he [grandson, son of care recipient] takes up – Female, 49, York.

2.5 Experiences of people who had been providing care for at least a year

This section of the report provides findings from the focus groups and participants who had been providing care for at least a year. This section explores how their journey had progressed over time, particularly in relation to employment.

As time progressed, the themes outlined above continued to affect the individuals and their employment in the following ways:

-

No change to employment or hours worked – Participants who kept the same number of working hours did so with support from other family members to meet the care recipient’s needs. A key motivation for this was reported to be feeling they could not afford to work fewer hours

-

Adapted employment through changes to working patterns and / or career – Participants who adapted their hours to fit around their caring activities reduced the number of hours worked, moved to part-time employment or took up flexible shift work if the option was available. Participants felt this helped them stay in employment, whilst allowing them time to support their family member. There were also participants who turned down career progression opportunities out of concern about the effect the extra demand of their work would have on their caring responsibilities, or that their caring duties would affect their work performance

I had to drop my hours to care for him [her brother]. There wasn’t much of a choice to be made there – Female, North West Focus Group.

- Changed employment – Participants who had changed employment had moved to a more flexible sector, or a job which offered shorter working hours. For example, one participant had become a taxi driver as this allowed him to choose his hours and work around his caring activities

- Break in employment – Participants who had a temporary break in their employment reported both long-term unpaid leave and shorter-term paid leave. Access to this type of leave largely depended on the flexibility of the organisation participants worked for

I couldn’t get the time off to take my son to his appointments. I didn’t have much of a choice [to leave work] – Female, North West Focus Group.

[Leaving employment is] not the easy way out – you try and juggle, you try to keep drama out of the work place, but eventually it comes to a head – Female, South West Focus Group.

You lose your reliability, so even if you have a choice you don’t take on contracts, you kind of back off. You’re out of the market straightaway – Female, London Focus Group.

The two strongest themes that participants cited as prompting them to leave the labour market were the level of care they provided and their type of employment.

- Level of care – When the level of care required increased, individuals began to feel less able to combine work and caring activities. For example, if the care recipient’s health condition worsened and they required more support this would affect their ability to combine work and care

- Nature of work – Participants in full time work or who had an employer who lacked understanding found it increasingly difficult to combine work and care. There was little knowledge of their employment rights, making it more likely that they would leave the labour market

In addition to making changes to their employment, those with more experience of providing care faced other challenges.

Participants described feeling that, over time, they lost their self-identity and confidence. Their entire focus was on caring for the other person and participants described feeling that the other person’s needs were always greater than theirs. This loss of identity was heightened in those who left the labour market. They reported feeling that being a full-time carer meant they had lower social status as people did not understand what they did. Lack of recognition from society exacerbated their loss of confidence. This had a detrimental effect on their confidence in returning to work.

You don’t realise how important work is [until you leave]. If you’re at work, even for just a few hours, it can boost your self-esteem….and it’s part of who you are – Female, North West Focus Group.

There were also reports of feeling isolated. Those who had left the labour market felt that doing so removed important social ties. Participants also felt that their caring responsibilities meant that they had less time to spend with their friends and that their friends would not understand their experiences as a carer as they were so different to their own lives.

Participants also noted facing financial difficulties. Leaving the labour market, or working fewer hours, reduced their income. As well as day to day challenges meeting living expenses, participants worried that this made it difficult for them to save for the future, specifically their retirement.

Amongst participants who had left the labour market there was enthusiasm to return. Whilst participants providing intensive caring support found it hard to see how they could combine work and caring, they were doing voluntary work where possible as they felt that this would be flexible and reflect their needs. Participants in this position were working with their local carer’s centre to help them prepare to return to the labour market. However, supporting their relative remained their main priority, which led to anxiety about how, and whether, they could combine work and care.

If you’d asked us that question about work when we were in work we’d have had more we disliked. Now it looks like a brilliant place to be! – Female, London Focus Group.

Case Study

A female participant who needed a period of leave approached her employer about taking leave in order to adjust to her new caring responsibilities.

After returning to work after three months, her employer had felt they had met the needs of the participant, believing the caring requirement to have been finite, rather than a continuous process.

The employer was less understanding of the participant’s needs to both stay in her position and care for her father, subsequently she felt she needed to move to another job in order to continue caring activities for her father.

3. Information Seeking

This chapter explores the information and sources that people sought once they began caring activities; how information needs can change over time and what people wished they had known at the start of their journey.

3.1 Questions people had early on

Initial information searches tended to be reactive and focused on supporting the care recipient in the short-term, rather than long term needs or support for the participant. This was because providing care could feel overwhelming, particularly in conjunction with other commitments. Participants reported focusing on getting through each day as it came and managing needs as they arose and not having the time or energy to think beyond these. This seemed to act as a barrier to taking a long-term view.

I’ve just been putting out each fire as it lights up. I haven’t had time to think that far into the future about help – Female, 54, Nottingham.

Upon beginning care activities, participants reported having questions about how to manage their situation. What emerged from this study was that upon beginning care activities, participants were starting from a low knowledge base about what support there was to help them.

Participants’ initial questions were about the health condition of the care recipient. Little was known about this before diagnosis, leading to feelings of fear and uncertainty. Participants wanted to better understand the condition, treatment and prognosis. However, those supporting a child or a partner who felt anxious about the prognosis or potential outcomes reported being reluctant to search for in-depth information about conditions out of fear of bad news, such as if the condition was likely to deteriorate or was untreatable.

I don’t think about it [her daughter’s condition]. I get too upset – Female, 49, York.

Participants also had questions about what financial help might be available to them, or the recipient of care. They sought to establish this when they knew more about the condition and its implications. Participants who reported searching for this information did so as a reaction either to the recipient of care having to stop work or needing more support than they could provide at that time.

People who were supporting someone with a physical health condition looked for information about home modifications, wheelchairs or accessibility aids, including entitlement for disability parking badges. People were often unsure what they might be entitled to and called their local authority to find out.

I called up [name] council. I wasn’t sure what she [his mother] would be entitled to, but I thought I could call and ask – Male, 60, London.

3.2 Sources of information used

The sources used by people in the early stage of their caring journey reflects a reactive approach to information seeking. Rather than proactively searching for specific information, people responded to information given to them. Moreover, participants said that they were not able to search for specific things online as they did not know what they should be searching for. These findings remained true throughout the caring journey for individuals who were providing more intensive care as the time they had to look for information was limited.

Regardless of their point in their caring journey, participants felt that offline sources were better suited to answering broad questions and signposting further information. Online sources were seen as being suited to answering detailed or specific questions. Participants felt that being shown that other people were in the same position as them reduced feelings of isolation and demonstrated that there was support available to them.

I haven’t been looking [online for information], because I didn’t know that I could look for anything – Female, East Midlands Focus Group.

3.2.1 Offline sources

Offline sources, such as healthcare professionals and family or friends with similar experiences, were discussed as being early touchpoints, providing initial information and advice about the diagnosis or condition of the recipient of care.

In particular, participants cited healthcare professionals as a regular point of contact and key source of information. Participants were in regular contact with healthcare professionals such as GPs, nurses and doctors from hospitals, as they supported their family member. However, participants reported that conversations focused on the care recipient and that healthcare professionals were unlikely to have raised the issue of their wellbeing with them.

I can remember so many of the conversations [with the GP] were about my mother’s condition. Looking back, there wasn’t nearly enough focus on who was going to be providing the care for her – Female, 50, Nottingham.

People also reported discussing their experiences with friends and family, particularly those who had similar experiences in the past. As well as a source of informal information, this also acted as a form of emotional support.

Local charities or support groups were also noted by participants. Rather than proactively search for these organisations, people reported finding out about them by chance, for example when walking past, through word of mouth or local advertising.

Case Study

A participant initially looked for emotional support from family members when caring for his mother, but some were distant and frustrated by his mother’s condition, which had worsened in the past year.

He looked to his local authority for professional support, and his GP for information on his mother’s condition, but not for information about supporting himself. He saw an advert for Age UK and called their helpline.

He uses the helpline once a month, both to explore what support is available for his mother and also to talk to someone that he feels understands his situation.

3.2.2 Online sources

As with offline sources, people in the early stage of their journey were pointed towards online information sources by other people, rather than proactively searching for this themselves. Lack of certainty about what they were looking for was another challenge to using online sources. People felt they did not have the time or energy to navigate the vast amounts of information available on the internet. Even when participants knew what they wanted to find, they felt it could be difficult to do so or to assess its legitimacy and accuracy. people defaulted towards sites that were well known or they trusted.

After working all day, it’s hard to motivate yourself [to search for information]. You could be looking for hours and not find what you’re looking for, then find it and second guess yourself as to whether it’s legitimate – Male, 52, Nottingham.

Sites such as the NHS and GOV.UK webpages were reported to be well known and trustworthy and used for information in the early stages of the journey. NHS webpages tended to be the first port of call for information on the recipient of care’s condition, whilst GOV.UK was used for information about financial or other support. People were familiar with the NHS and government. This familiarity, and the perceived legitimacy derived from being government bodies gave people confidence that the information would be accurate.

As with offline sources, people were also directed towards online sources through word of mouth, or through seeing a site advertised.

Participants went to the websites of condition specific charities, for example, Alzheimer’s Society, Age UK, MacMillan, Dementia UK. People reported liking the tailored information for the condition that the care recipient suffered from and clear guidance on what to expect when someone is experiencing that condition. It was also felt that these sites had an empathetic tone. Participants also reported that these sites were likely to offer emotional and practical support for the person providing care, as well as the care recipient. These sites also signposted to other sites offering wider support, such as financial advice.

Financial advice sites such as Money Saving Expert were used to understand what financial support might be available and participants were directed to them by word of mouth. People placed high levels of trust in Money Saving Expert and recognised the website’s founder, Martin Lewis, as a well-respected financial expert. They felt the site was on the side of the individual, providing useful advice in interactions with government and financial institutions. This trust extended to feeling that it is on the side of people providing care, providing information they may otherwise find it difficult to access. Participants were signposted to these sites from other online sources or through word of mouth.

My friend sent me to Martin Lewis Money Saving Expert and it said that ‘you’re living with dementia, you might not have to pay council tax’. How is my father [with dementia] supposed to find that [he doesn’t have to pay council tax] out [otherwise]? There’s a lot of information out there but it can be hard to find – Female, North West Focus Group.

Local Authority websites were seen as a useful way of accessing locally relevant information. This was important as participants reported many support services were provided locally or that provision, for example for professional care, was locally determined. However, participants also reported finding Local Authority websites were hard to navigate and contained outdated information or broken links. Participants also found that these sites adopted a functional tone, which made the content seem less warm and supportive.

People used social media sites such as Facebook to access support and informal information, such as joining groups that shared similar experiences of care activities. This allowed people to share concerns about their care recipient’s condition, as well as express experiences, and potentially frustrations, that they did not feel comfortable sharing with their immediate social circle or family.

The experiences participants relayed of using online and offline information sources shows that one source could not address all user needs, even if it contained all the relevant information. For example, whilst there is trust in Government websites participants also saw value in charities, which could offer specific advice on the condition the care recipient was experiencing and third party organisations perceived to act as advocates for individuals, such as Money Saving Expert.

3.3 How information needs changed over time

Within this sample identifying as a carer strongly influenced how people looked for information. Doing so moved them in to a space where they could look for, and access, support for themselves and this was the key change to information sought over time. Reflecting on this, participants described feeling frustrated that these networks and information had been invisible and inaccessible to them.

I didn’t see myself as a carer, so it’s almost impossible to look for things to help you with your situation – Female, London Focus Group.

It’s taken me three years to get to this point, now. I read this [carer’s] centre’s website in tears [as it made me realise I was not alone and could get support] – Female, London Focus Group.

After identifying as a carer, participants looked for information to support themselves: social networks and financial support. Interacting with other networks of carers helped participants to feel less isolated. These networks also opened them up to options such as volunteering and, with support from someone at the carer’s centre, looking for ways back in to the labour market.

When carers get together and start talking, that is when we learn new things – Female, East Midlands Focus Group.

Beyond enabling access to additional sources of information to support their own wellbeing, the information needs of those who had been providing care for a number of years were consistent with those of people in the earlier stages. They wanted information about the care recipient’s condition, particularly if this was progressive, or the support available could change. They also wanted access to information about external support, for example, childcare.

3.4 What did participants with more experience of providing care feel people should know at the outset?

People who had been providing care for a number of years were asked what advice they would give to working people in a similar position now.

Participants said they would have wanted to understand they were a ‘carer’ sooner because of the support it unlocked. This raises the question of how this information should be positioned so that people can be supported to access it sooner, regardless of whether they identify as a carer or not.

Participants also described wanting information and support to have been given to them proactively by others. They felt they needed someone to reach out and help them, as there were times that they needed help but were not aware or able to articulate their needs because they were so focused on providing support to their family member.

Participants also felt that they needed information on the financial support that they and/or the care recipient might be entitled to as early as possible. Participants reported that this was useful to help mitigate the financial challenges associated with providing care. For example, some participants with savings reported not looking for financial support initially, but in retrospect felt it was unfair that they spent their own savings when support could have been available. In addition, people unable to work due to providing care may be able to get National Insurance credits, which participants recognised as important for protecting their future eligibility for a State Pension.

Participants also felt that they would have wanted information on their employment rights as someone proving care activities, particularly entitlement to leave, or flexible working. This would help people to understand the options for combining work and caring. Participants felt that this knowledge could have opened up more options. As it was, there was a strong feeling amongst those who had left the labour market that at the time they had no choice but to leave their job due to their caring responsibilities. Amongst this group there were those who wondered whether they could have stayed in employment with the right support.

Being a carer can be a minefield… particularly around employment rights, there needs to be clear and concise information – Female, South West Focus Group.

My employer has suggested I cut my hours from 18 to 14 a week… I’m trying to progress my career but you get overlooked for certain tasks, trainings, promotions. I’m not sure what rights are there – Female, North West Focus Group.

Participants also felt it would have been valuable to know that they could access emotional and practical support, such as support networks for carers such as carers centres.

The problem is, when you first start caring, you’re expected to know things that you just don’t know. It needs to be basic where someone sits down with you and talks through everything at the very start [of caring for someone] – Female, North West Focus Group.

3.5 What support people further along the carer journey wanted when interviewed

Those further along the caring journey who were not in employment were keen to find information on how to re-enter the labour market but had low confidence about doing so. These participants worried about having to explain gaps in their work history, as they did not feel that caring was viewed positively or understood by employers. They also worried that their skills had become out of date, particularly those who had worked in sectors which required technical skills such as IT as they felt at risk of their skills becoming outdated quickly.

I’m finding it very difficult to find work. Leaving jobs [to care] and having gaps in employment doesn’t look good on my CV – Female, North West Focus Group.

Those further along their caring journey also reported that they needed more support for their own health. They felt that providing care placed a great physical, mental and emotional strain on them but it was difficult to make sure their own wellbeing was considered. This was even though they recognised that not doing so could cause more problems in the long term as, if they were unable to provide care someone else would need to do so.

I think there needs to be information and support for carers to look after themselves. If the carer’s health suffers, then the person they’re caring for suffers… if the carer can’t work [due to ill health], then you run out of money and more and more problem arise – Female, North West Focus Group.

4. Implications for the improvement of information

This chapter outlines implications emerging from the research about how information for people providing care, particularly those in the early stages of doing so, can be improved.

4.1 Implications

Proactively supply information to support the needs of people providing care

Participants were primarily focused on supporting the care recipient’s needs and did not report proactively seeking information about their own wellbeing or employment either online and offline. However, participants who had been providing care for longer reported that, in hindsight, they wanted to have accessed information to support their wellbeing sooner. To do so, participants felt they would have needed to be either proactively given information or encouraged to consider their own needs by touchpoints in the caring journey, such as nurses and doctors, including GPs.

Make more use of offline sources to reach those providing care and signpost to further information online.

Participants discussed regularly interacting with offline sources such as GPs and hospitals in the course of providing care. Leaflets and posters in GP practice and hospital waiting areas were reported as being particularly helpful sources of information. As participants were there regularly in their role providing care the information would be in the right context for them to engage with it. These forms of communication were seen as a helpful way of raising awareness of the type of support available.

I just happened to see a leaflet at the GP that said, ‘are you a carer’. I thought ‘no’, but then I read it and thought, I do all of what’s being said here – Female, London Focus Group.

One example of this working successfully was carers centres directing people to online resources. Participants felt that they had more trust and certainty in these sources when they had been directed there by the carer’s centre. Ideally, people would experience this signposting earlier on in their experiences of providing care.

Target carers more explicitly through online sources in the care recipients’ journey.

Participants reported accessing websites about the care recipients’ condition and needs, for example, those with a defined condition would look to condition specific charity websites or to GOV.UK for the support available for them.

These websites could more explicitly reference the individual providing care and help signpost them to information about support for themselves.

Design information for time-poor users and make it easier to process.

Participants reported that providing unpaid care affected the time they had to seek out and process information. Ensuring information is clear, concise and easy to navigate may help make information easier to process.