Work Coach provision of employment support

Published 25 May 2023

DWP ad hoc research report no. 84

A report of research carried out by Ipsos and the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2023.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence or write to the

Information Policy Team

The National Archives,

Kew,

London

TW9 4DU

Email [email protected]

This document/publication is also available on our website at Research at DWP.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email [email protected]

First published May 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-530-0

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

1. Executive summary

The Institute for Employment Studies (IES) and Ipsos were asked by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to produce a report in response to a series of recommendations made by the Public Accounts Committee. The Committee recommended that:

a) The Department should commit to undertaking and publishing a full evaluation by the end of 2022 of how well its Work Coaches provide employment support and how consistently they apply their judgement

b) The Department should gather and use systematic feedback on claimants’ satisfaction with their Work Coaches, the service at the Jobcentre, and how the Jobcentre could be improved

Starting in summer 2021, IES and Ipsos undertook a wider research project for DWP, from which relevant findings could be drawn. The time period covered by this project was January 2021 [footnote 1] -October 2022. The research involved a nationally representative survey of 8,325 Universal Credit customers, 60 follow-up interviews with survey participants, and a series of case studies in 10 Local Authority areas.

The survey research included customers who started in the Intensive Work Search regime [footnote 2] who had participated in Plan for Jobs provision [footnote 3] and those who had not participated or had left the provision early. The follow-up qualitative interviews with survey participants included equal numbers of customers who were either employed, unemployed (and looking for work) or unemployed (and not looking for work) at the time of the interview. The case studies included in-depth qualitative interviews with Jobcentre staff and DWP operational staff (including local leaders), provider staff delivering local employment support provision, and UC customers who had participated in Plan for Jobs employment support programmes. A summary of these findings is presented below.

Overall, the findings from a nationally representative survey of Universal Credit customers showed that satisfaction with their regular Work Coach and the support they offered was generally high. Specifically, the majority of customers participating in Plan for Jobs provision agreed that they were receiving an adequate level of support from their Work Coach to move into work; that the discussions they were having were personalised to their own career aspirations; that their needs were listened to; and that they felt confident in asking for employment-related support.

Where satisfaction rates were slightly lower, this was among groups of Universal Credit customers not participating in Plan for Jobs provision who were more likely to face additional barriers to employment (e.g. on the grounds of their health or caring responsibilities). Taken together these findings suggest that, in broad terms, Work Coaches’ approach to providing employment support was working for many customers, particularly those who were closer to the labour market.

The survey and in-depth qualitative research linked customer satisfaction to:

- Personalised discussions taking place about customers’ skills and career aspirations;

- Work Coaches demonstrating an understanding of customers’ personal situations and listening to their needs;

- Work Coaches suggesting employment support provision, training courses or job roles that were appropriate to customers’ capabilities and needs.

The in-depth qualitative work with Jobcentre staff showed that, on balance, Work Coaches felt they took a person-centred approach in how they work with customers. However, with the survey research showing slightly lower rates of satisfaction among customers who, proportionally, tended to face more barriers to employment, it may be that the degree of personalisation Work Coaches were able to provide for these groups was limited on occasions.

The findings from the in-depth qualitative research provided more details on the experience of those customers who had an unsatisfactory experience of support and identified some of the structural issues that affect the level of personalisation Work Coaches were able to provide. Bringing together the findings from the Jobcentre staff, provider and customer interviews, it appeared that in some case study areas where Work Coaches lacked clarity about the nature of employment support provision, this was impacting on the referral experience of customers. Providers and customers highlighted cases where, following a referral, the customer was unclear on what the provision entailed and how it was relevant to their personal circumstances.

In the view of Jobcentre and provider staff, these issues were particularly pronounced following the introduction of the government’s Plan for Jobs measures in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Interviewees noted that the introduction of several new employment support programmes alongside an expansion in the number of Work Coaches made it more difficult, at least during the early stages of their rollout, for staff to feel confident in their knowledge of the local employment support offer. New Work Coaches were trained relatively quickly to help process the large number of benefit claims that occurred during the pandemic, which was a priority for DWP during this time.

Some measures were identified as helpful to addressing these challenges, however. This included:

- Having one Work Coach act as a single point of contact for each national employment support programme to help promote the provision, answer queries and share success stories within the Jobcentre

- The regular co-location of provider staff in Jobcentre offices to promote and share information on their programmes among Work Coaches and customers and facilitate warm handovers on occasions, although this was not possible during times when stricter Covid-19 restrictions were in place

Another view expressed among some customers who participated in the qualitative research was that interactions with their Work Coach could feel very one-sided and that the Work Coach was ‘going through the motions’, following their standard processes and procedures without tailoring the support offer to the needs of the customer. This was evident in the types of job vacancies that were suggested, which some customers judged were not relevant to their circumstances; this included interviewees with health conditions and caring responsibilities.

Again, linking this evidence to provider and Jobcentre staff feedback, these experiences could be related to the requirement for Work Coaches at the time of the research to meet their office profiles for Plan for Jobs provision. Staff felt that this requirement could lead to referrals being made that were not necessarily in the customer’s best interests but were based on their eligibility for a specific programme. Among customers, these experiences might result in a lack of trust in their Work Coach and a view that they are not taking their personal circumstances into account. Customers were more likely to say that the support they received was not personalised where they did not regularly see the same Work Coach.

The claimant interview findings highlighted that these experiences could negatively affect a customer’s relationship with their Work Coach and their initial level of engagement and buy-in for any employment support programme they were referred to. According to provider staff, this could have knock-on implications for the likelihood of customers starting on a programme.

Reflecting on these experiences, the customers interviewed generally wanted better communication from their Work Coach about the support available to them and an increased level of personalisation in terms of the types of job opportunities presented. An increased amount of privacy within Jobcentre offices when customers were meeting with their Work Coach was also put forward as a way of supporting open two-way conversations and personal disclosures that were relevant to a customer’s job-search.

However, while these measures could result in a more positive referral experience for a customer, the time pressures Work Coaches face day-to-day, and the fast pace interviewees reported working at, did make it more challenging to consistently deliver a more personalised support experience for customers.

2. Introduction

In 2022, the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) and Ipsos were asked by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to produce a report in response to a series of recommendations made by the Public Accounts Committee. The Committee recommended that:

a) The Department should commit to undertaking and publishing a full evaluation by the end of 2022 of how well its Work Coaches provide employment support and how consistently they apply their judgement.

b) The Department should gather and use systematic feedback on claimants’ satisfaction with their Work Coaches, the service at the Jobcentre, and how the Jobcentre could be improved.

At the time of the recommendations, IES and Ipsos were undertaking a wider research project for DWP, from which relevant findings could be drawn. This report presents findings for the time period January 2021-October 2022, although fieldwork for this wider project finished in April 2023. The research completed during this period involved a nationally representative survey of Universal Credit customers within the Intensive Work Search regime, follow-up qualitative interviews, and a series of case studies in 10 Local Authorities. The case studies included in-depth qualitative interviews with Jobcentre staff, provider staff delivering local employment support provision, and customers within the Intensive Work Search regime. Further details on the approach taken are set out below.

2.1 Methods

The survey research comprised of 8,325 interviews with Universal Credit customers in early 2022. This included customers that had participated in Plan for Jobs provision and those who had not participated [footnote 4] or had left the provision early. A representative sample was drawn in autumn/winter 2021/22 for each of these groups to facilitate the interviews. Customers participating in each Plan for Jobs strand were weighted to their respective participant profile (excluding the Youth Offer), and non-participants were weighted to the profile of all eligible customers not engaging with Plan for Jobs. All data were weighted by gender, length of claim, and region. Early leavers data was unweighted.

A series of qualitative interviews was also completed with 60 customers who took part in the survey research and agreed to be recontacted. The interviews took place between September and October 2022. It included both participants and non-participants in the government’s Plan for Jobs provision. Equal numbers of interviews were achieved with customers who were either employed, unemployed (and looking for work) or unemployed (and not looking for work) at the time of the interview.

The case study research took place in 10 Local Authorities. The selected areas were places with the most need for employment support and the highest barriers to achieving job outcomes. In making the case-study selection, areas included rural and urban locations; areas across England, Wales, and Scotland; as well as geographies with regional governments given their different funding structures and political contexts. Each case-study included qualitative interviews with several stakeholders; Jobcentre staff and DWP operational staff (including local leaders); provider staff involved in delivering employment support provision locally; customers; and wider partners. Over 300 interviews were completed with stakeholders and customers between October 2021 and August 2022. The content of this report draws more heavily on the interviews completed with Jobcentre staff, DWP operational staff and customers in order to address the Public Accounts Committee recommendations.

2.2 Limitations

In terms of the survey research and in-depth follow-up interviews, while the design of the survey is reliable, there are several factors and caveats to consider when discussing the results and implications:

- Self-reported measures: All results are self-reported and have not been verified. For instance, whether a customer has been referred to another employment-support programme, organisation or accessed further support has not been verified. Evidence suggests that customers were often confused/not confident about who was delivering the support (DWP or other organisation) and might be unable to differentiate between the various types of organisations or types of support. The data presented in this report is based on their stated answers.

- Customer recall: There is a gap between the sampling period (April-October 2021) and the survey fieldwork period (February – March 2022) which might have affected respondent’s recollection. However, this was necessary to ensure enough time had elapsed for sampled customers to start an employment-support programme so they could be surveyed on their experiences.

- Generalising findings: The sample of participants taking part in Plan for Jobs provision are not representative of all participants in these strands to date. They were selected from a specific cohort of people who started on this provision from mid-2021 to the end of October 2021. As such, the sample is representative of customers receiving support during this period.

For the case study research, as noted, the 10 case study areas focused on locations where, across different economic activity and population measures, job outcomes may have been more difficult to secure. As such, these cases are not necessarily representative of the experiences of Jobcentre staff, employment-support providers and customers more widely.

In addition, the case studies were focused on how the government’s Plan for Jobs employment support strands were integrated into existing support systems and processes. The interviews with stakeholders sought to gather information on the entire local support landscape, but were designed to focus more heavily on how the Plan for Jobs strands were working in practice given the aims of the research. This will have affected the balance of evidence and depth of information collected on these topics.

Finally, given the focus of the case study research, customers were sampled for interviews from across the Plan for Jobs strands. Efforts were made to interview a diverse sample of customers to capture a range of different experiences. However, given the qualitative nature of this element of the study, this sample is not representative of customers engaged in this provision more widely.

3. Provision of employment support by Work Coaches

This section of the report summarises evidence on how well Work Coaches provide access to employment support and how consistently they apply their judgement when deciding which support option will be most appropriate for a customer. It draws on the in-depth interviews completed with Jobcentre staff and providers during the case study research and covers: Work Coaches’ level of awareness of the local employment support landscape; the factors that influence their decision making about which programmes to refer customers to; their practical experiences of the referral process and with providing customers with timely access to support.

3.1 Work Coaches’ level of awareness of the local employment support landscape

The interviews completed with Jobcentre staff demonstrated a good overall awareness of the local employment support landscape. Interviewees were able to describe various programmes they could refer customers to covering basic skills (specifically, maths and English), employability, and work-related skills via short vocational courses. Specialist provision was also discussed in many case study areas for individuals with disabilities or learning differences, mental health issues, or for Armed Forces veterans and prison leavers. Knowledge of this specialist provision often came from staff that occupied specialist roles within the Jobcentre, such as Youth Employability Coaches. Longer term work and training opportunities, such as Traineeships and Apprenticeships, were not mentioned during these interviews and did not appear to be a referral option that was often considered by Work Coaches or the Jobcentre more widely across case study areas.

While staff interviewed demonstrated a good level of awareness of the local provision landscape across case study areas, some Work Coaches commented that the scale and variety of provision they could access in their office at times felt overwhelming and was confusing to navigate. Work Coaches were clear that time pressures and the fast pace at which they needed to work created challenges in absorbing and sharing updates and information on local provision among staff. These issues were highlighted several months after various employment-support programmes had been introduced as part of the government’s Plan for Jobs, which sought to respond to the Covid-19 economic downturn and added greater complexity to the local support landscape.

The introduction of new, DWP-contracted provision would often be accompanied by a training session for Work Coaches, delivered by the local provider. This would outline the support available, the programme’s eligibility criteria, which customers would be suited to the provision and any success stories from customers who had previously taken part. Some Work Coaches interviewed stated that this was a useful starting point in building their understanding of any new programme. However, often interviewees felt that their confidence in making use of new provision developed gradually over time, as they brought these programmes into their day-to-day conversations with customers.

In our job it becomes a bit like muscle memory when you’re working throughout the day because you’re working so fast and then they bring in something new and suddenly it’s trying to incorporate that into your day as well. As they drop it into every other meeting or bring people in to talk about the good news stories or how they can be supported by other colleagues from that provision it makes it less scary and adds in that bit of “I can do this”. You sort of incorporate it into your day and it gets a bit easier.

Work Coach

Across many of the Jobcentre offices that participated in the research, Single Points of Contact (SPOCs) were nominated for the main DWP funded provisions available for customers. These staff members were allocated to a specific programme and were the main point of contact for Work Coaches in that office if they had any queries about the programme. These points of contact would also disseminate success stories amongst staff and try and keep their allocated programme at the forefront of Work Coaches’ minds. This aimed to support referrals and help offices to meet the referral profiles they had been allotted for this provision. In some offices, SPOCs also played a role in reviewing the referrals that had been made to their provision, to ensure that these were appropriate and in line with the specified eligibility criteria.

Despite these measures to build and maintain Work Coach awareness of DWP contracted provision, both providers and customers that participated in the case study research highlighted instances where they felt that Work Coaches lacked clarity on the nature of the support customers would receive once they started a particular programme. This led to some confusion among customers and provider staff about why certain referral decisions had been taken, the relevance of the selected provision to customer circumstances and what support needs the programme could help the customer address (and what they could not help with).

Some provider staff helping to deliver Plan for Jobs provision felt that this issue was particularly pronounced in 2021 as several employment support programmes were introduced around the same time. While this was happening, Jobcentres were also increasing their capacity and hiring new Work Coaches. New Work Coaches were trained relatively quickly to help process the large number of benefit claims that occurred during the pandemic, which was a priority for DWP during this time. Taken together, provider staff felt that these factors may have made it more challenging for Work Coaches to absorb information about both new and existing provisions and accurately reflect this in their daily practice.

As Covid-19 restrictions eased over the course of 2021/22, providers of local employment support provision (including nationally commissioned programmes) began to have more of a physical presence in Jobcentres and co-locate on set days of the week where possible. This practice was commonplace prior to the pandemic and viewed positively by both provider and Jobcentre staff. Providers noted that having a presence within Jobcentres helped in building relationships with Jobcentre staff, continually reminded Work Coaches of their support offer, and ultimately encouraged more referrals to their provision over time. Interviewees also commented that co-location enabled Work Coaches to hand over customers to providers for a more detailed discussion about the customer’s circumstances and how the support offer could help them. This saved Work Coaches time in their appointments with customers and helped ensure that customers received more accurate and up-to-date information about what the programme would entail, how it could help them and the reason for their referral.

3.2 Work Coach referral decision-making

Across the case study research, Work Coaches were asked to describe during interviews what influenced their decisions on which employment support programmes to refer customers to.

Work Coaches felt, on balance, that their referrals were based on customers’ level of work readiness and the nature of the barriers they faced to labour market participation. However, Work Coaches also described several other factors that could influence their referral decision making. These varied between offices and over time, across the course of the case study fieldwork. This included:

- The requirement to meet office profiles for Plan for Jobs provision

- Some Plan for Jobs provision being viewed as low quality by some Work Coaches following early customer feedback, with local/regional referral options being preferred instead

- Turnover among Work Coaches, leading to less consistent knowledge about the available provision

- A lack of clarity about which parts of the Plan for Jobs offer customers can access following participation in an initial strand

3.3 Requirement to meet office profiles

Working through each of these points in turn, the requirement to meet office-level referral profiles for Plan for Jobs provision came up consistently as an influence on Work Coach decision-making at the time of this research. These unofficial targets, set at the Jobcentre district and office-level, are based on levels of anticipated need among customers. They help ensure that commissioned providers across the country receive enough customer referrals to meet their agreed KPIs with DWP.

Work Coach Team Leaders commented that they were held accountable for trying to increase referrals to meet these profiles. Where profiles were not being met, the Team Leaders would be questioned on this by their managers and could be asked to put improvement plans in place if this continued over time. It should be noted that the need to meet these profiles was not strictly enforced and there were no obvious, direct penalties for offices or staff that did not meet their allotted profiles over a protracted period. Instead, Work Coach Team Leaders described how they would seek to understand from Work Coaches why they were not referring to certain programmes and would encourage them to look at how they could try and increase this by identifying eligible customers and bringing the provision into more of their daily conversations.

If someone hasn’t referred to any provision then it would be my role to sit with that person and understand why. It may just be they had a particularly bad day and found they were overwhelmed and didn’t have time, or it may be genuinely that they did ask the claimants and it wasn’t suitable or the right time for them.

Work Coach Team Leader

While the need to meet referral profiles was not strictly enforced, from the Jobcentre staff interviews it was clear that the organisational requirement to meet these profiles still existed and could run counter to a customer-centred approach. For example, some staff described situations in which they felt there were better referral options available for a customer locally. However, for some staff, the requirement to meet profiles for certain provisions swayed their decision and led them to suggest a support programme that may not be the best fit for the customer’s needs.

Examples of this practice were cited in relation to the Restart programme, especially during the early stages of its implementation when the provision had tighter eligibility criteria. When the provision was rolled-out, the labour market was beginning to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic with employment rising. This changed the make-up of the claimant population by enabling more job-ready customers to move into work. As such, those that were eligible for the programme (individuals that had been out of work for 12 to 18 months) generally presented with more significant barriers to labour market participation. Some of the Restart providers interviewed highlighted that their contract was not adequately resourced to support people with complex needs who either may not be able to work or required more intensive support to move closer to employment. However, the need to meet profiles for this provision from a smaller pool of suitable customers led to some of these customers being referred. In the view of providers, this was inappropriate in meeting customer needs:

I think what we’ve seen as well is inappropriate referrals coming onto the programme because the Jobcentre have targets to achieve, they have to get those referrals on so they do refer the people that probably aren’t ready for Restart, people that are on fit notes, people that they may be in the intensive work search regime but then they’re not able to work at this time. Is a mandatory provision the best route for that individual at this time? Probably not, it probably should be more Work and Health, something more voluntary to build them up to then lead them to Restart. But I think Jobcentres are under a lot of pressure. Work Coaches have a very hard job, they’re under a lot of pressure to be referring to the programme

Provider staff

It should be noted that following these early delivery experiences, the eligibility criteria for the Restart programme were widened and the number of referrals Jobcentres were required to make were adjusted down in accordance with need.

Even providers of Plan for Jobs provision noted that referrals to their programmes declined as new provision was rolled out. Job-Entry Targeted Support (JETS) providers in several case study areas, for example, saw their referrals decline temporarily following the introduction of Restart, despite these programmes having different eligibility criteria. In the view of these providers, this demonstrated the influence that profiles have on Work Coach referrals, and the limited pool of customers that Work Coaches could refer from during this period.

3.4 Plan for Jobs provision in some areas being viewed as low quality and duplicating existing local support

The case study research also surfaced a countervailing influence on some Work Coach referral decisions. This related to the perceived quality of some Plan for Jobs provision and the availability of other local support options. In some areas, early customer feedback on some of these programmes was poor. This dissuaded some Work Coaches from referring to this provision. Instead, these Work Coaches referred customers to providers who they had a history of working with and had an established reputation in the area for this type of support.

However, these services were seen to gradually improve over time in the affected case study areas after these experiences were fed back by Work Coach Team Leaders to DWP operational staff within their district, who in turn passed this feedback on to the providers concerned. This improvement, coupled with the office-level profiles allocated to this provision, encouraged Work Coaches in the affected areas to make greater use and refer more customers to these programmes over the course of their delivery.

3.5 Turnover among Work Coaches

As noted, the introduction of several Plan for Jobs measures and the hiring of new Work Coaches over the course of 2020-2021 was seen to affect Work Coaches’ level of awareness of the employment support system and what each programme involved, at least on a short-term basis. This in turn could affect the quality and appropriateness of referral decisions, from a provider and customer perspective.

Jobcentre staff also highlighted that turnover among Work Coaches more generally could have a similar effect on collective knowledge and confidence in the best referral routes for customers. This could vary between offices and was linked to the other employment opportunities available locally. Interviewees reflected that staff in offices with high levels of turnover and lots of new starters had more limited opportunities to draw on experienced colleagues for advice and support. In some areas Customer Service Leaders believed this affected the number of referrals Work Coaches made, with those offices with higher staff turnover seeing fewer referrals to Plan for Jobs provision compared to offices with lower turnover rates. In one case study area, for example, turnover was seen to affect customer referrals to Kickstart vacancies, which required a degree of coordination and occasional case conferencing between staff.

From the interviews with some new Work Coaches, there also appeared to be a lack of consistent training on long-established employment support programmes, which also affected their knowledge of the local provision landscape and ability to make informed referrals:

I still don’t really know what a SWAP is, but I know what it stands for but when I started everyone was talking about SWAPs and there was never anything put in place to tell you what a SWAP was.

Work Coach

3.6 Questions over customer eligibility

Across the case study research, some Jobcentre staff were unsure about customer eligibility for Plan for Jobs provision where customers had taken part in other DWP-funded employment support programmes recently. This seemed to be a specific issue for the Plan for Jobs strands, with a lack of clarity among Work Coaches about whether customers could access a second programme following participation in an initial programme. This in turn was seen to affect Work Coaches’ ability to make confident decisions on referral pathways for a customer. To address this, staff felt that information about Plan for Jobs provision and how each specific programme complemented and worked within the wider employment support system should be provided.

4. Referral processes and customer access to timely support

4.1 Work Coach referral processes

For longer term provision, such as Restart, the referral process was seen as time-consuming for Work Coaches, as they had to arrange a three-way call between themselves, the customer and the provider. These ‘warm handovers’ were generally viewed as beneficial in supporting customer engagement with the programme as Work Coaches were on hand to clarify anything and support them through the process. This was felt to be particularly helpful for customers with anxiety or other mental health problems who could be nervous about engaging with an external provider. Work Coaches, however, noted that it took time to arrange these three-way calls as they needed to find a slot that was suitable for all three parties. Some interviewees highlighted that the time allocated for individual customer appointments and subsequent administration was not sufficient to complete a Restart referral in a single appointment, which led to delays in customers’ engagement with the programme.

Where Work Coaches felt that Restart might not be the best support option for eligible customers (for example, because they had significant, complex needs that needed to be addressed before they could consider entering employment), interviewees said they were required to have a case conference with their Work Coach Team Leader to discuss this decision and reason for referring to an alternative programme. For some experienced Work Coaches, this introduced an unnecessary layer to the referral process: they felt that they should not have to justify their referral decisions and were confident in identifying the provision best suited to their customer’s needs.

5. Claimant satisfaction with Work Coaches and the service at the Jobcentre

This chapter presents findings that give an insight into claimant satisfaction with Work Coaches and the service provided at the Jobcentre. It draws on the customer survey and the in-depth interviews completed with customers as part of the case study research, which were designed to explore customer perceptions of Plan for Jobs provision.

The survey findings are presented first, detailing customers’ level of satisfaction with the frequency of contact with their Work Coach and the level of support they provide. The survey research comprised of 8,325 interviews with Universal Credit customers in the Intensive Work Search Regime between 3rd March and 10th April 2022. In keeping with how the survey findings were collected, these results are presented for those customers engaged in DWP-funded Plan for Jobs provision [footnote 5] (46% of the sample) [footnote 6], as well as non-participants in these programmes (42% of the sample) and customers who left this support early (9% of the sample) [footnote 7]. It should be noted that in terms of characteristics, slightly higher proportions of non-participants and those that left the support early had either physical or mental health issues and/or some form of caring responsibilities compared to the rest of the sample.

The findings from the follow-up qualitative interviews completed with 60 survey participants and interviews with customers completed as part of the case study research are then set out covering three key themes: customers’ views and experiences of the support they have received from their Work Coach, their experiences of the referral and handover process to employment support providers, and any gaps and improvements in support identified by customers.

5.1 Survey findings: customer satisfaction with their Work Coach and the level of support provided

The survey findings showed that customers engaged in Plan for Jobs provision met with their Work Coach, on average, every two to three weeks. Across the various programmes, between 76 and 82 per cent of these customers said they were satisfied with this level of contact. Customers not engaged in this provision and those who left the support early reported meeting with their Work Coach, on average, every two weeks. For these latter groups, satisfaction was slightly lower, with 64 per cent of non-participants and 72 per cent of customers who left provision early stating that they were happy with this frequency.

Customers were also asked a series of questions on their satisfaction with the level of support Work Coaches provide. Rates of satisfaction were again high for those customers engaged in Plan for Jobs employment support programmes. Among non-participants and early leavers, satisfaction was again slightly lower, suggesting that some Work Coaches may find it more difficult to offer personalised support to individuals who are more likely to face additional barriers to employment (perhaps due to their health or caring responsibilities).

For example, across the different programmes, between 73 and 79 per cent of participating customers agreed that their Work Coach provided the support they needed to help them back into work. This compared with 56 per cent of non-participants and 66 per cent of people who left their programme early. Survey results also showed that between 74 and 80 per cent of customers engaged in Plan for Jobs provision felt the discussions they had with their Work Coaches were relevant to their career aspirations, compared with 57 per cent of non-participants and 67 per cent of early leavers.

In addition, customers engaged in Plan for Jobs provision were more likely to agree that their needs were listened to by their Work Coach than those not engaged in these programmes. Between 77 and 81 per cent of customers participating in Plan for Jobs programmes agreed their needs were listened to, compared with 62 per cent of non-participants and 71 per cent of early leavers. Further, between 80 and 83 per cent of participants in Plan for Jobs provision agreed that they feel comfortable asking their Work Coach for employment-related support. This was again lower amongst non-participants and early leavers at 64 and 76 per cent, respectively.

5.2 Customers’ views and experiences of support

In-depth interviews completed with survey participants and as part of the case-study research captured more varied and nuanced customer experiences of Work Coach support and the service at the Jobcentre.

The interview findings frequently highlighted the influence a positive Work Coach relationship can have on a customer’s progression toward work. A more positive relationship was often reported to secure a higher level of customer engagement in regular appointments. With this, both Work Coaches and customers felt they were able to have more productive conversations on the progress of the customer’s job-search, which ultimately was seen to lead to better outcomes. Where a less positive relationship was reported however, customers would discuss feeling inadequately supported throughout their time at the Jobcentre.

In-depth interviews with customers outlined the common features that support an effective Work Coach relationship. This included: personalised discussion of skills and career aspirations, empathy for their personal situations, and encouragement to apply for courses and job roles relevant to these needs. Each of these is discussed below.

5.3 Personalisation of support

Personalised support was highlighted as important in ensuring customer engagement with the services of both the Jobcentre and external employment support providers. Where customers felt their support was more personalised, they were able to discuss their career and skill aspirations more openly and in greater detail, as well as any additional barriers facing their entry into employment. Through conversations about their interests, capabilities and circumstances, Work Coaches and customers were able to explore available support options together and secure the most informed and potentially useful referral. An example of this experience from the case study research was shared by an individual seeking a role in the creative sector. They described discussing their creative passion with their Work Coach and was subsequently introduced and referred to Restart, where they were able to receive more tailored career guidance.

In contrast, other customers taking part in the case study interviews discussed not experiencing this same level of personalised support. Rather, several reported feeling that the support they were referred to by their Work Coaches was not beneficial in their journey towards employment. For example, some customers interviewed felt that their career and skills aspirations were not fully taken into consideration when discussing opportunities available within their local area with their Work Coach. Instead, they discussed frequently being sent standardised vacancy lists through their journal with roles not relevant to those discussed with their Work Coach or set out in their claimant commitments.

I said [to my Work Coach] you keep offering me jobs that I’m not happy in. Unless I’m happy in a job I’m not going to stay there and I’m not going to work.

Customer

Some customers experiencing physical and mental health conditions that limit the types of work they can do also discussed their experiences of being encouraged to apply for roles they had already said were not suitable. One individual that participated in the case study research discussed leaving the hotel industry due to the impact this work was having on their mental health. They expressed discomfort about the prospect of returning to the industry but felt pressurised by their Work Coach to do so. Another customer discussed an ongoing medical investigation into their chronic back pain with their Work Coach, but felt they were continually encouraged to apply for roles that required long periods of standing. The follow-up interviews with survey participants supported these findings, with customers with high levels of need describing their frustration at the short amount of time they had during their appointments to discuss these needs with their Work Coach.

I appreciate they’re under pressure and they’ve got to [get us into work], but there didn’t seem to be any care at all, not one bit for the jobseeker.

Customer

Some of the customers interviewed as part of the case study research were able to reflect on the support they had received throughout Covid-19 lockdown periods and compared this with more recent experiences. Customers felt the support throughout lockdown periods when there was no work search requirement was much more focused on addressing skills gaps and additional barriers to employment, which they preferred as it felt more productive. In contrast, their reflections on more recent experiences of support (i.e. autumn 2021 to summer 2022) described a less holistic, more work-first focus.

5.4 Taking an empathetic approach

Some customers interviewed reported a high level of satisfaction with the support their Work Coach was able to provide around personal circumstances. Customers indicated that in cases where a Work Coach had an empathetic approach, they felt able to disclose more information about their personal situation. Having this increased level of disclosure further allowed the Work Coach and customer to discuss relevant support options and the opportunities available to them. Through this, customers highlighted an increased focus on support tailored to address their personal needs, rather than support being primarily work-focused.

My wife’s pregnant and has health issues, so it’s a bit of a struggle… At one point it was really difficult for me to get to the Jobcentre myself… they did help us quite a bit during that time.

Customer

In contrast, some customers participating in the case study research said that their Work Coach did not take their personal situation into consideration when discussing their work search and possible support options. These customers indicated that their interactions with their Work Coach felt procedural and transactional. This was highlighted by groups including parents of young children, who felt their need for work or training opportunities that could fit around care responsibilities was not a primary focus for their Work Coach. Similarly, some individuals taking part in both the case study research and follow-up interviews who were experiencing poorer mental health felt that this was overlooked by their Work Coaches and not appropriately addressed during their conversations. While regular appointments with a Work Coach did help to reduce feelings of isolation and improve the wellbeing of some customers within this group, without openly discussing their mental health needs, these customers did not always feel that appropriate employment or support suggestions were being put forward by their Work Coach. This group of customers wanted Work Coaches to be more willing to have conversations about their mental health, and to be understanding of and accommodate these needs in the support they provided.

5.5 Views on encouragement and advice

Throughout the case study research, Work Coaches and wider partners commonly perceived an overall decrease in confidence amongst customers since the onset of the pandemic [footnote 8]. Several customers added to this, discussing the challenges of identifying employment opportunities and moving into work given the turbulent labour market during this time, and the impacts this had on their confidence around employment. In addressing these issues, the follow-up interviews with survey participants showed that young people in particular found the advice provided by Work Coaches on what to include in their CVs and the language they should use when applying for jobs beneficial.

When discussing what further support they felt could have improved their confidence, some customers noted that they would have benefitted from more encouragement from their Work Coach to apply for roles and courses relevant to their interests. The follow-up interviews with survey participants showed that those interviewees looking to gain further qualifications or retrain to work in a different sector were not aware of what support the Jobcentre were able to provide to facilitate this.

Some customers interviewed as part of the case study research felt increased encouragement could also be facilitated through more detailed discussions around transferrable skills, and the ways in which these can be applied to some of the roles being suggested to them by their Work Coaches. In particular, some young people suggested they could benefit from tailored career counselling, with manageable steps to progress toward their desired career outcome.

Some of the customers that participated in the follow-up interviews who had higher needs and were non-participants in Plan for Jobs provision also reported that low self-confidence was a central issue for them. These interviewees wanted a greater level of personalised support on this issue, did not believe that Jobcentre staff were well positioned to help them address these needs.

6. Customers’ experiences of referrals and handovers to employment support

6.1 Referrals to employment support

Interviews with customers often highlighted the importance of fully informed referrals and efficient handovers to any employment-support provision to secure high levels of satisfaction and early buy-in. Where customers reported having more detailed conversations with their Work Coach about the support options available, they generally expressed higher levels of satisfaction with their referral and support experience. Some explained that entering provision with a good understanding of the help they could receive boosted their confidence about the support offer and any subsequent employment.

[My Work Coach] just said [JETS] were probably a lot more tailored to my skill set and that they’d have a lot more opportunities available… the Jobcentre were very limited in the time they could spend with me. I thought it was a great opportunity.

Customer

Interviews with customers highlighted that the level of trust they had with their Work Coach also influenced their initial level of buy-in and engagement in a support programme, as well as their willingness to access further support if this was required. This was particularly important in circumstances where a customer was experiencing high levels of anxiety about moving into work. The follow-up interviews with survey participants showed that a sustained relationship with the same Work Coach was important in fostering trust with a customer by providing a familiar and consistent point of contact. However, this was not the predominant experience among this group, with several interviewees saying that they spoke to a different Work Coach every time they visited the Jobcentre.

On occasions, customers participating in the case study research stated that they were referred to an employment support programme by a Work Coach who they had seen on a one-off basis and was not their regular coach. This generated a sense of distrust in the referral; customers were sceptical about whether the support would be appropriate and beneficial.

In addition, several customers interviewed as part of the case study research felt that they were provided with little information about the support they were being referred to. Rather, customers often expressed being unsure and, in some instances, feeling misinformed about what the support offer would entail when they were being referred. These customers felt that they only gained this information once they had met with the provider. Customers reporting this discussed feeling that the referral was not tailored to their personal needs, and in many cases did not seem to provide them with any additional support. This could further damage the level of trust they had with their Work Coach, as well as their own confidence.

The way [my Work Coach described the support] it seemed it would be a calm ease into work, and the first time I spoke to the woman at JETS I discovered it was more like a fast paced, get you up and running again thing… it kind of put a damper on my confidence… it did make me a bit anxious.

Customer

Some customers participating in the case studies also discussed being under the impression that once they had spoken to their Work Coach about a particular support programme, they would then be mandated to that support and have to engage with it as part of their claimant commitment. This perception, in some cases, discouraged them from wanting to take part in the provision as they felt they were being pushed toward opportunities that did not align with their desired outcomes [footnote 9]. The follow-up interviews with survey participants who did not participate in Plan for Jobs employment support provision suggested that feelings that Work Coaches were punitive in their approach was the result of inconsistent contact with the same Work Coach or prior experience of sanctions.

6.2 Experiences with the handover process

Throughout the interviews, customers often discussed their experiences of handover processes positively. Several reported that the introduction to their adviser at their respective provision was straightforward and happened quite quickly following their referral, and that they appreciated the more detailed explanation of the support offer provided during this meeting. In some cases, customers highlighted that they entered an employment support programme after just a few days of being introduced to the provision by their Work Coach. Through these examples, it was notable that those who experienced a more efficient handover reported a higher level of satisfaction than those who had to wait longer to receive support.

I saw my Work Coach on the Tuesday, I received the phone call from JETS on the Thursday morning, emails came through Thursday afternoon and I had my first Teams meeting on the Friday… it was a very quick process.

Customer

In contrast, some customers interviewed shared their experiences of slower and incomplete referrals, and on occasion expressed dissatisfaction with their Work Coach’s follow-up with providers to ensure the referral was complete. In these instances, customers reported feeling that they were held in limbo, awaiting calls from providers while receiving little communication about the state of their referral from their Work Coach.

[My Work Coach] said they would call me. They didn’t phone. Then they said another place would phone me. They didn’t phone.

Customer

Several customers interviewed, who were long-term unemployed, were able to discuss their experiences of handover processes to multiple providers. Most commonly from these discussions, customers highlighted that they had to outline their experience, capabilities and desired employment and training outcomes to each provider. Additionally, customers had to repeat their personal circumstances and any barriers preventing them from moving into employment or training. Interviewees highlighted that this process felt increasingly repetitive and made them feel there was little communication between the organisations they were in touch with. This made the support experience feel disjointed. They reflected that these repeated introductions could perhaps be better facilitated by the Jobcentre in future.

Initially [I was] feeling comfortable about being pushed from one organisation to another, but you can only do that so often… there was no communication between different organisations.

Customer

7. Gaps and improvements in support identified by customers

7.1 Communication and transparency

Throughout the case study research, customers were asked to identify ways in which they felt the service and support they received at the Jobcentre could be improved. Customers repeated that the communication between themselves and their Work Coach could be better. Specifically, customers wanted greater openness and transparency about the range of support options available to them, and the processes and procedures involved in accessing this support.

Customers often felt that they were following Jobcentre processes without a full understanding of what the process entailed, and the outcome these processes would achieve. This was felt particularly acutely among customers who were referred to external support organisations without a detailed introduction to the support. In some cases, this presented a barrier to forming a Work Coach-customer relationship built on trust. In the interviews, customers expressed that they would like to have a better understanding of the processes being followed so they had a better line of sight of the next steps in their journey at the Jobcentre. This added level of transparency from the Work Coach would facilitate a more trusting relationship with the customer, increasing their engagement in appointments.

In addition, some customers discussed feeling that their relationship with their Work Coach was very one-sided. Often, customers commented that after their Work Coach sent work opportunities to them via their online Universal Credit account, they would receive several messages and calls asking about their progress with applications and their job-search. When, however, these customers reached out to their Work Coach through their Universal Credit account, they indicated that they would have to wait extended periods of time to receive a response. While these customers highlighted that they appreciated the workload pressures Work Coaches are under, they felt that they would benefit from a more reciprocal, supportive relationship in which communication was open and accessible.

Another communication challenge identified by customers during interviews regarded the additional support available through the Jobcentre. Customers often highlighted that they were unaware of the Jobcentre’s discretionary ability to fund transport, childcare and formalwear for interviews, and workwear for new employment, which is subject to an assessment of customer need. Customers indicated that they would have liked this information to have been made available early in their claim to provide a more informative introduction to Jobcentre processes and build their awareness of what additional support they could access.

I’m not sure what support there is out there… I’m not quite sure on how the benefit system works. I’m not sure how much childcare is covered, what they cover it for.

Customer

7.2 The Jobcentre environment

Another common area for improvement suggested by customers participating in the case study research was the Jobcentre environment. Customers interviewed felt that the open plan layout of Jobcentre offices offered no privacy during appointments, which was particularly important for individuals discussing their personal circumstances. Rather, customers were often discussing their circumstances in front of other Work Coaches and customers, which caused them to feel uncomfortable and, in some cases, less likely to disclose information that could have implications for their work search. Findings from the follow-up interviews with survey participants suggested that these changes, together with reducing the visible presence of security guards, would also support customers who have had poor experiences with the Jobcentre in the past by creating a more welcoming environment.

While customers appreciated the need for the public health measures in place due to the pandemic, Covid screens were identified as another contributing factor towards a lack of privacy within the Jobcentre. Customers discussed having to raise their voice so their Work Coach could hear them. To eliminate this discomfort, some customers felt the Jobcentre could provide more flexibility in terms of the mode of their appointments, saying that discussing personal circumstances over the phone would make them feel more comfortable and would support a greater degree of openness on their part.

Every person is sat a foot away from you at the next appointment, they can hear everything.

Customer

7.3 Increased personalisation of support

The final area for improvement suggested by several customers in the case studies was an increase in the level of personalised support provided by Work Coaches. As set out, customers often stated that they were being sent employment and training opportunities that did not align with the job goals set out in their claimant commitments, and which they had not expressed any interest in working in. In some instances, customers recalled being sent employment opportunities for jobs requiring experience they did not possess. In others, they would receive a blanket list of jobs from a range of sectors and skill levels. This caused customers to feel that the content of their discussions with Work Coaches was not being fully considered and that their Work Coach was pushing them into any available employment outcome.

In instances where customers felt that their desired outcomes and personal circumstances had been taken into account by their Work Coach, they reported a much higher degree of satisfaction with their service and their subsequent outcomes. For example, single parents who were sent work opportunities that were suited to their childcare responsibilities displayed a high degree of satisfaction with their outcomes.

I did tell [my Work Coach] specifically that the jobs I was looking for were around the health sector, but that they had to be flexible hours [due to childcare]. She recommended about four… I applied for all, they seemed really interesting, and I chose the one I’m in at the moment.

Customer

The follow-up interviews with survey participants also indicated that high levels of customer satisfaction were achieved in cases where customers regularly saw the same Work Coach, which enabled a relationship of trust to be established and supported Work Coaches to understand a customer’s circumstances more fully. This approach was seen to be particularly beneficial for more vulnerable groups of customers, such as young people with mental health issues. However, this was not the predominant experience among interviewees.

8. Conclusions

The findings presented in this report aim to provide an insight into how well Work Coaches provide employment support and how consistently they apply their judgement. They also put forward evidence of claimant satisfaction with their Work Coaches and the service at the Jobcentre.

Overall, the findings from a survey of Universal Credit customers showed that satisfaction with their regular Work Coach and the support they offer was generally high. Where satisfaction rates were slightly lower, this was among groups of customers not participating in Plan for Jobs employment support provision who were more likely to face additional barriers to employment (e.g. on the grounds of their health or caring responsibilities). These findings suggest that, in broad terms, Work Coaches’ approach to providing employment support was working for many customers, particularly those who were closer to the labour market.

The survey and in-depth qualitative research linked customer satisfaction to:

- Personalised discussions taking place about customers’ skills and career aspirations;

- Work Coaches demonstrating an understanding of customers’ personal situations and listening to their needs;

- Work Coaches suggesting employment support provision, training courses or job roles that were appropriate to customers’ capabilities and needs.

The in-depth qualitative work with Jobcentre staff showed that, on balance, Work Coaches felt they took a person-centred approach in how they work with customers. However, with the survey research showing slightly lower rates of satisfaction among customers who, proportionally, tended to face more barriers to employment, it may be that the degree of personalisation Work Coaches were able to provide for these groups was limited on occasions.

The findings from the in-depth qualitative research provided more details on the experience of those customers that had an unsatisfactory experience of support, and identified some of the structural issues that affect the level of personalisation Work Coaches were able to provide. Bringing together the findings from the Jobcentre staff, provider and customer interviews, it appeared that in some case study areas where Work Coaches lacked clarity about the nature of employment support provision, this was impacting on the referral experience of customers. Providers and customers highlighted cases where, following a referral, the customer was unclear on what the provision entailed and how it was relevant to their personal circumstances.

There was also a view among some customers who participated in the case study research that interactions with their Work Coach could feel very one-sided and that the Work Coach was ‘going through the motions’, following their standard processes and procedures without tailoring the support offer to the needs of the customer. Again, linking this evidence to provider and Jobcentre staff feedback, these experiences could be related to the requirement for Work Coaches to meet their office profiles for Plan for Jobs provision. Interviewees felt that this requirement could lead to referrals being made that were not necessarily in the customer’s best interests but were based on their eligibility for a specific programme. Among customers, these experiences could result in a lack of trust in their Work Coach and a feeling that they are not taking their personal circumstances into account. These feelings were also more likely to be reported where customers did not regularly see the same Work Coach.

The interview findings highlighted that these experiences could negatively affect a customer’s relationship with Work Coaches and their initial level of engagement and buy-in for any employment support programme they were referred to. According to provider staff, this could have knock-on implications for the likelihood of customers starting on a programme.

The case study research highlighted ways in which these issues could be mitigated by providing customers with more information and a greater sense of how the employment support offer was relevant to their needs. This included:

- Having single points of contact (SPOCs) for each national employment support programme in Jobcentre offices to help promote the provision, answer queries and share success stories;

- The regular co-location of provider staff in Jobcentre offices to help promote and share information on the programme among staff and customers;

- Co-location could also facilitate warm handovers between the provider, customer and Work Coach. This could ensure that relevant information was communicated about the customer and that they felt supported throughout the process.

While these measures could result in a more positive referral experience for a customer, the time pressures Work Coaches face day-to-day and the fast pace interviewees reported working at, alongside the turnover of Work Coaches and the impacts this has on their collective knowledge of the local support offer, do make it more challenging to consistently deliver a more personalised support experience for customers.

9. Annex

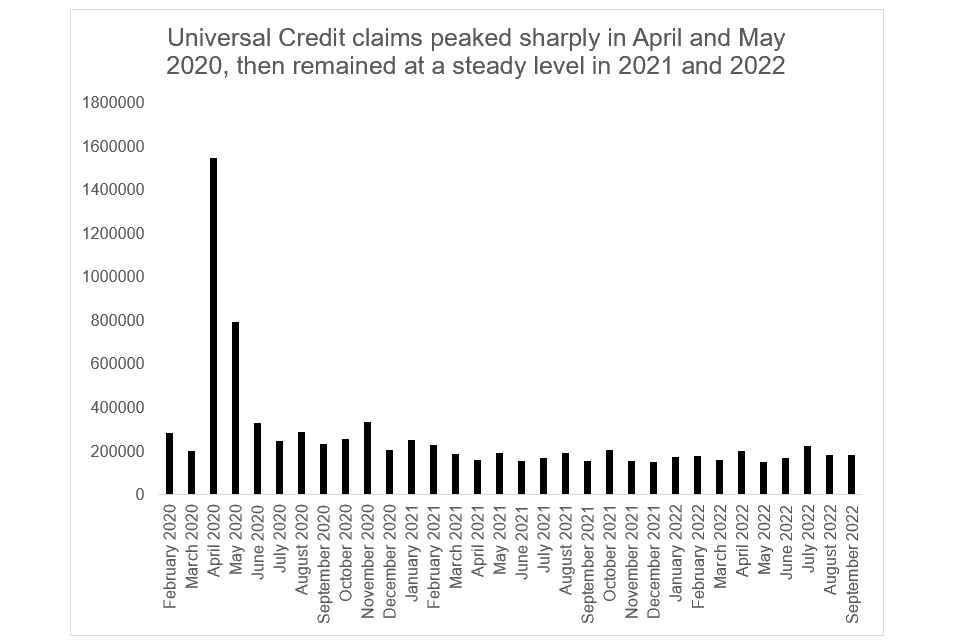

Claims to Universal Credit: February 2020 to September 2022

| Time period | Claims |

|---|---|

| February 2020 | 283,459 |

| March 2020 | 202,468 |

| April 2020 | 1,547,017 |

| May 2020 | 793,065 |

| June 2020 | 327,016 |

| July 2020 | 244,291 |

| August 2020 | 286,453 |

| September 2020 | 232,757 |

| October 2020 | 253,396 |

| November 2020 | 332,325 |

| December 2020 | 203,027 |

| January 2021 | 249,394 |

| February 2021 | 229,706 |

| March 2021 | 188,294 |

| April 2021 | 157,637 |

| May 2021 | 188,905 |

| June 2021 | 154,069 |

| July 2021 | 167,486 |

| August 2021 | 191,240 |

| September 2021 | 152,642 |

| October 2021 | 203,125 |

| November 2021 | 152,530 |

| December 2021 | 149,776 |

| January 2022 | 171,674 |

| February 2022 | 175,288 |

| March 2022 | 158,141 |

| April 2022 | 201,415 |

| May 2022 | 151,097 |

| June 2022 | 166,631 |

| July 2022 | 225,356 |

| August 2022 | 180,580 |

| September 2022 | 183,156 |

Source: Universal Credit Official Statistics from DWP Stat-xplore, April 2023

( https://stat-xplore.dwp.gov.uk/ )

-

In the earlier phases of the research project, respondents were asked to retrospectively discuss their experiences from the start of 2021 onwards ↩

-

This refers to customers who are not working, or who are working but earning very low amounts. These customers are generally expected to take intensive action to secure work or more work unless their conditionality has been altered for reasons such as having a work-limiting health condition. ↩

-

This comprised of the introduction and expansion of several employment support programmes including: Job-Entry Targeted Support (JETS), Job Finding Support (JFS), Sector-based Work Academies (SWAPs), Kickstart and the Youth Offer. ↩

-

Non-participants were Universal Credit customers in the Intensive Work Search group that were not participating in one of the Plan for Jobs strands ↩

-

At the time of the research, these were the DWP’s Plan for Jobs employment support programmes. ↩

-

Restart participants were excluded from the sample as they were used for a separate study. However, 273 customers told us they were or have taken part in Restart when interviews. This data has been excluded from the findings presented here as it is not representative of all Restart participants. ↩

-

Customers who left the support early were those participants that stated they dropped out and did not complete one of the government’s Plan for Jobs employment support programmes. Customers will have left the programme for a variety of reasons including finding work or because the supported offered was not right for them. ↩

-

It should be noted that fieldwork for the case study research and follow-up interviews took place from autumn 2021 to autumn 2022. These findings do not reflect confidence levels among customers since that time. ↩

-

The interview findings are self-reported, so it is not possible to verify whether customers were being mandated to engage in a support programme in these instances. ↩