Balance sheet analysis and farming performance, England 2022/23 - statistics notice

Updated 20 December 2024

Applies to England

This release presents the main results from an analysis of the profitability and resilience of farms in England using data from the Farm Business Survey. Six measures have been examined; liabilities, net worth, gearing ratio, liquidity ratio, net interest payments as a proportion of Farm Business Income (FBI), and Return on Capital Employed (ROCE). The results cover the survey period from March 2022 to the end of February 2023.

Key results

-

In 2022/23, the average (mean) level of liabilities, also known as debt, across all farms was £294,600, an increase of 8% from 2021/22.

-

The average net worth across all farms was £2.2 million in 2022/23 and 49% of farms had a net worth of at least £1.5 million.

-

The average gearing ratio across all farms was 12% in 2022/23, which is a figure largely unchanged over the last decade.

-

The average liquidity ratio was 321% in 2022/23, marking the fifth year of consecutive increases.

-

Net interest payments were, on average, 8% of Farm Business Income (FBI) in 2022/23, a rise of 2 percentage points from 2021/22.

-

The average (median) ROCE was 0.5% in 2022/23, a fall of 0.5 percentage points compared to 2021/22.

Points which apply throughout

-

The Farm Business Survey is the source for all data presented in tables and charts unless otherwise stated.

-

All figures relate to England, unless otherwise stated, and cover a March to February fiscal year, with the most recent year shown ending in February 2023. Fiscal years are shown in YYYY/YY format, for example, the period of 1 March 2022 to 28 February 2023 is shown as 2022/23. To ensure consistency in harvest/crop year and commonality of subsidies within any one Farm Business Survey year, only farms which have accounting years ending between 31 December and 30 April are included in the survey. Aggregate results are presented in terms of an accounting year ending on the last day of February, which is the approximate average of all farms in the Farm Business Survey.

-

Unless otherwise stated, values are expressed in current rather than real terms: - current (or nominal) values are the values expressed in historical monetary terms - real terms values are the current values adjusted to take inflation into account using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) deflator data, published 22 December 2023 at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/timeseries/ybgb

-

Due to the small sample sizes, pig and poultry farms have been combined into one farm type.

-

Per hectare results are calculated per hectare of farmed area, where farmed area is Utilised Agricultural Area plus the net area of land hired in (i.e., the area of land hired in minus the area of land hired out).

-

The acronym ‘LFA’ refers to Less Favoured Area. These areas were established in 1975 to provide support to mountainous and hill farming areas. They are areas where the natural characteristics (geology, altitude, climate, short growing season, low soil fertility, or remoteness) make it difficult for farmers to compete.

-

Various breakdowns are shown in each sector which are generally ordered by the significance of the predictive variables, as determined by generalised linear models. For more information on the methods used, see section 8.4.

1 Liabilities

This section examines the indebtedness of farm businesses, as measured by their total liabilities. Liabilities are the total debt (short-term and long-term) that the farm business holds, including mortgages, long-term loans and monies owed for hire purchases, leasing and overdrafts. A farm with high levels of liabilities will require consistent income flows to ensure that interest payments can be met.

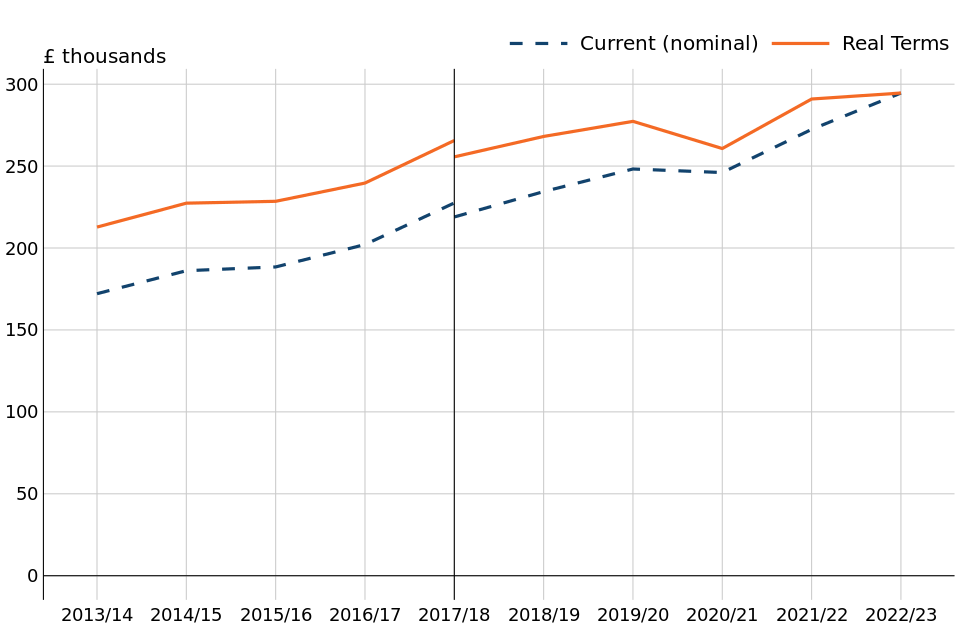

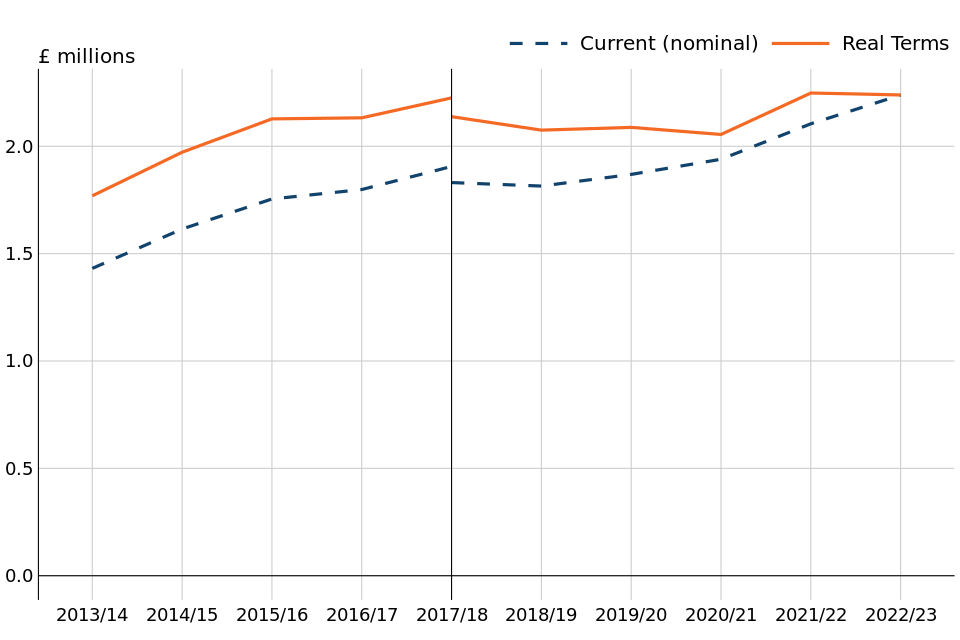

Figure 1.1 Average liabilities in current (nominal) values and real terms (2022/23 prices) in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. Real terms prices use the latest GDP deflator data, published 22 December 2023 at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/timeseries/ybgb.

2. The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average liabilities have been calculated using both methods for comparability.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 1.1 shows a ten-year time series of average liabilities per farm in both current and real terms. The average level of debt across all farms has been on a general upward trend since 2013/14, with a brief dip in 2020/21. In 2022/23, the average farm had liabilities of £294,600, an increase of 8% compared to the nominal value from 2021/22. However, in real terms, the 2022/23 value was only a rise of 1% compared to the previous year.

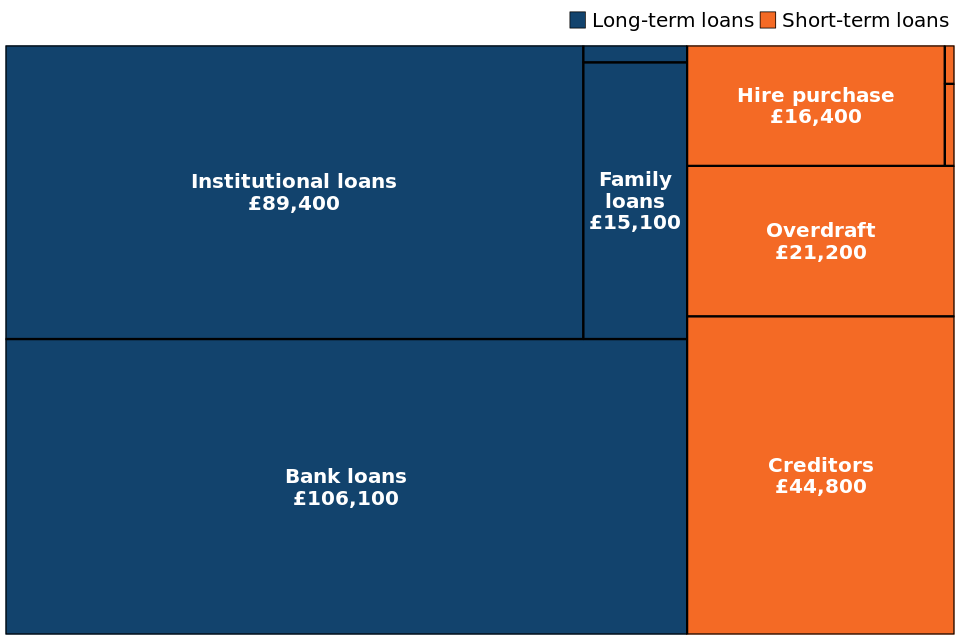

Figure 1.2 The composition of liabilities (£ per farm) for the average farm in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The size of the box for each category is proportional to its contribution to the overall average liabilities per farm.

2. In the long-term loans, the ‘Other loans’ (£900) category is too small to be labelled in the plot.

3. In the short-term loans, the ‘Other short-term loans’ (£400) and ‘Leasing’ (£200) categories are too small to be labelled in the plot.

Figure 1.2 shows the composition of liabilities for the average farm. The largest components of liabilities were bank loans (£106,100, or 36% of total liabilities) and institutional loans (£89,400, 30%).

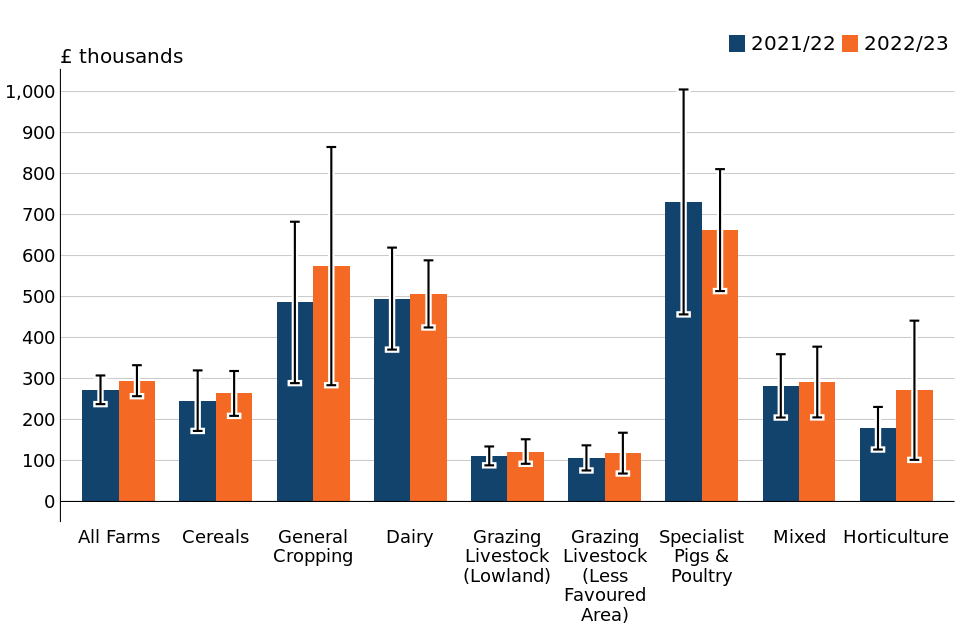

Figure 1.3 Average liabilities by farm type in England, 2021/22 and 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart includes a full time series, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 1.3 shows average liabilities by farm type in 2021/22 and 2022/23. In 2022/23, most farm types saw an increase in their levels of liabilities compared to 2021/22. The highest level of average liabilities in 2022/23 was seen in specialist pig and poultry farms, however, this was the only farm type whose average liabilities fell compared to the previous year, decreasing by 9% to £662,000. The largest rise in average levels of debt was seen in horticulture farms, which increased by 52% to £271,300 per farm in 2022/23. The lowest levels of debt of 2022/23 continued to be in grazing livestock farms, with average liabilities at £121,800 and £117,900 for lowland and LFA farms respectively.

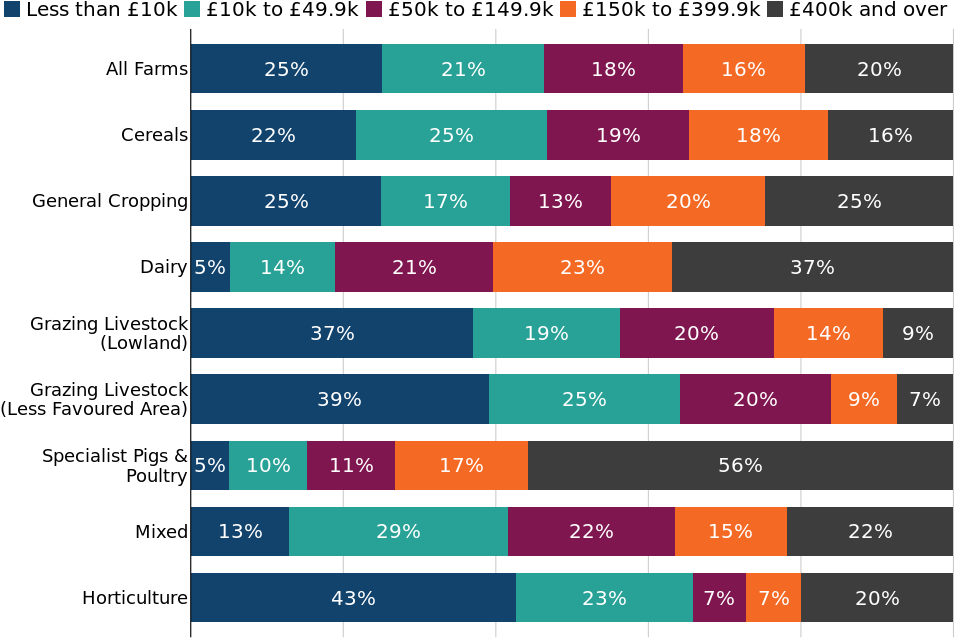

Figure 1.4 Distribution of farms by liabilities held and farm type in England, 2022/23

Figure note: The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 1.4 shows the distribution of liabilities within farm types in 2022/23. In general across all farms, there was little change from 2021/22 in the distribution of liabilities, with some variation within individual farm types (see Figure 1.5 of the 2021/22 publication for comparison). At the all farm level, a quarter of farms owed less than £10 thousand in 2022/23, while 20% had liabilities of £400 thousand and over. LFA grazing livestock farms had the lowest proportion owing at least £150 thousand, at 16%. Specialist pig and poultry and dairy farms had the most farms with liabilities of at least £150 thousand, at 73% and 60% respectively. These farm types also had the lowest proportion owing less than £10 thousand, at 5% each. Horticulture farms had the highest proportion owing less than £10 thousand, 43%.

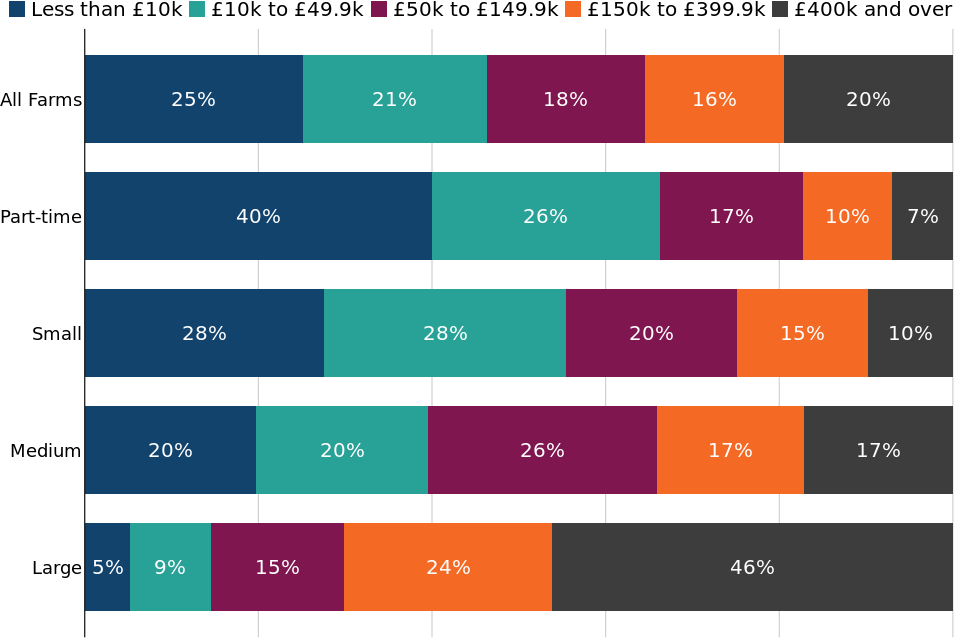

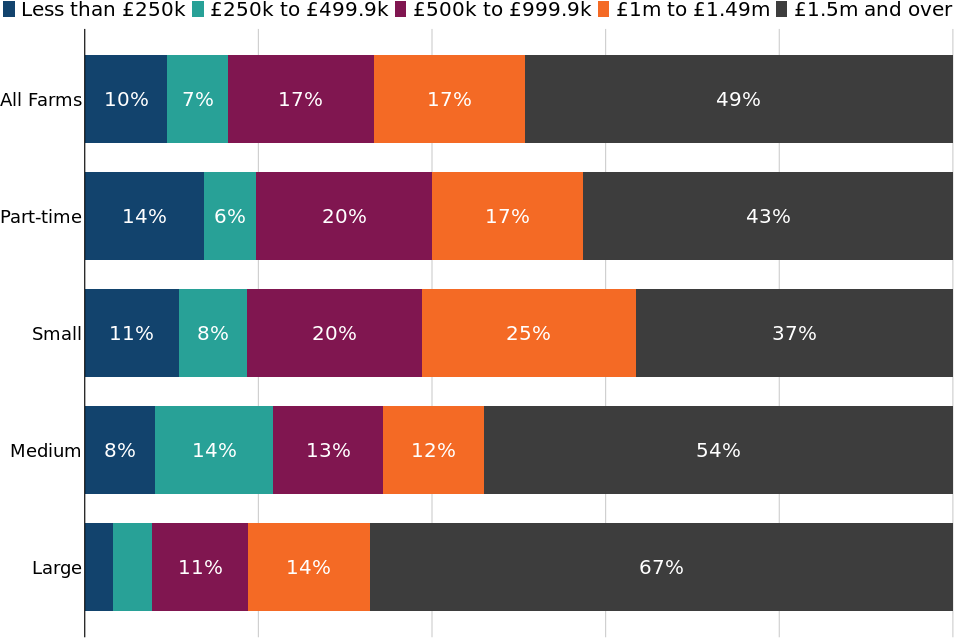

Farm business sizes are based on the estimated Standard Labour Requirement (SLR) for the business, rather than its land area. For more detail see Table 8.1. Last year we included ‘Very large’ farms as a size category, however, due to small sample sizes, this group has been merged with ‘Large’ farms for this publication.

Figure 1.5 Distribution of farms by liabilities held and farm business size (based on SLR) in England, 2022/23

Figure note: The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

While the average level of debt ranged from £123,200 to £190,900 for part-time to medium farm businesses, the value for large farm businesses was substantially higher, at £716,100. This pattern can be seen in figure 1.5, which compares liabilities by farm business size and shows that the proportion of farms falling into the higher bands increases with the size of the farm business.

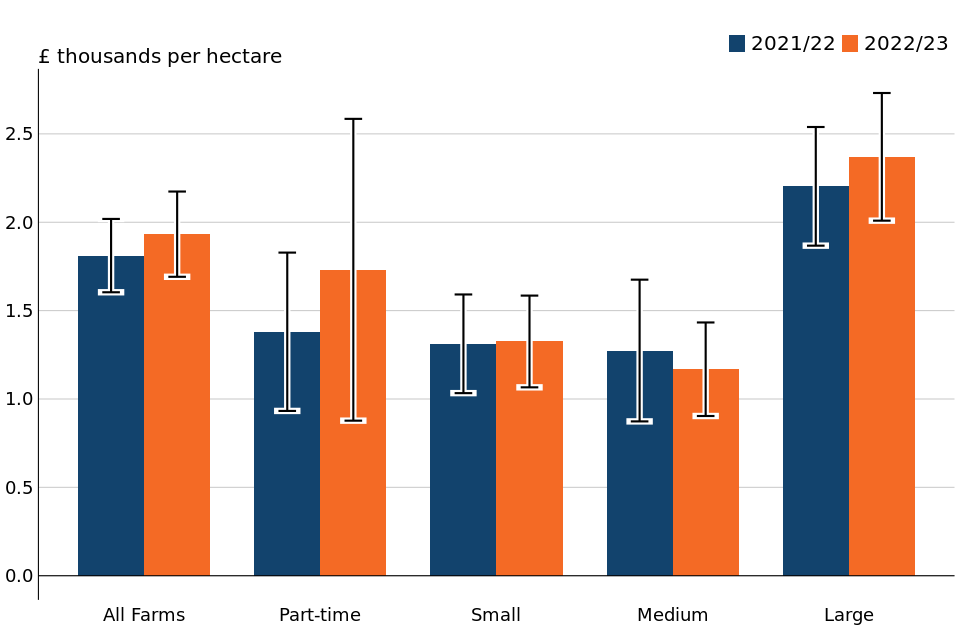

Figure 1.6 Average liabilities held by farms per hectare of farmed land by farm business size (based on SLR) in England, 2021/22 and 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart includes a full time series, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 1.6 shows the average liabilities per hectare by farm business size (based on SLR) in 2021/22 and 2022/23. With the farm area taken into account, the average amount owed decreases as the business size increases from part-time to medium, with medium farm businesses owing the least on average, £1,170 per hectare. However, the trend then reverses, with large farms owing the most on average, £2,370 per hectare. It is important to note, however, that the per hectare results for large farms may be distorted by the method used to classify farms into their sizes. Farm business size is categorised by labour requirements rather than farmed area and, except for crops in glasshouses, buildings are not included as part of the farmed area. This means that farms which keep animals housed will have a smaller farmed area, so can have much higher per hectare results than farms with the same labour requirements but which keep animals outside. Certain farm types are more likely to keep animals housed, such as pig and poultry farms. In addition, farms which require highly labour-intensive work over a small area, such as horticulture, will also be affected by this distortion.

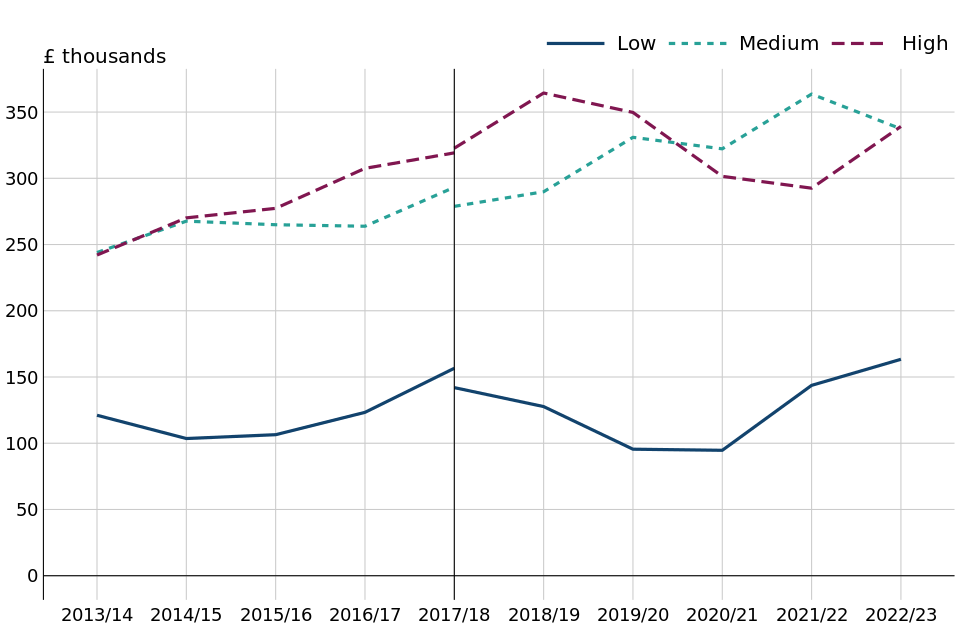

Figure 1.7 Average liabilities in real terms (2022/23 prices) by farm economic performance band in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure note: The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average liabilities have been calculated using both methods for comparability.

The data for this chart also includes current (nominal) terms values and breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 1.7 shows the real terms time series of average liabilities, split by economic performance band into the bottom 25%, middle 50% and top 25% of performers; these bands are labelled as ‘Low’, ‘Medium’ and ‘High’ respectively. Farms in the highest economic performance band saw liabilities rise sharply in 2022/23, increasing by 16% to £339,100, after a dip between 2018/19 and 2021/22. Average liabilities for medium performing farms have had a general trend of increasing, however, in 2022/23 they fell by 7% to £337,300. The average liabilities of farms in the bottom 25% of economic performers continued to be well below that of medium and high-performing farms, although the average did rise for the second consecutive year, increasing by 14% to £163,400.

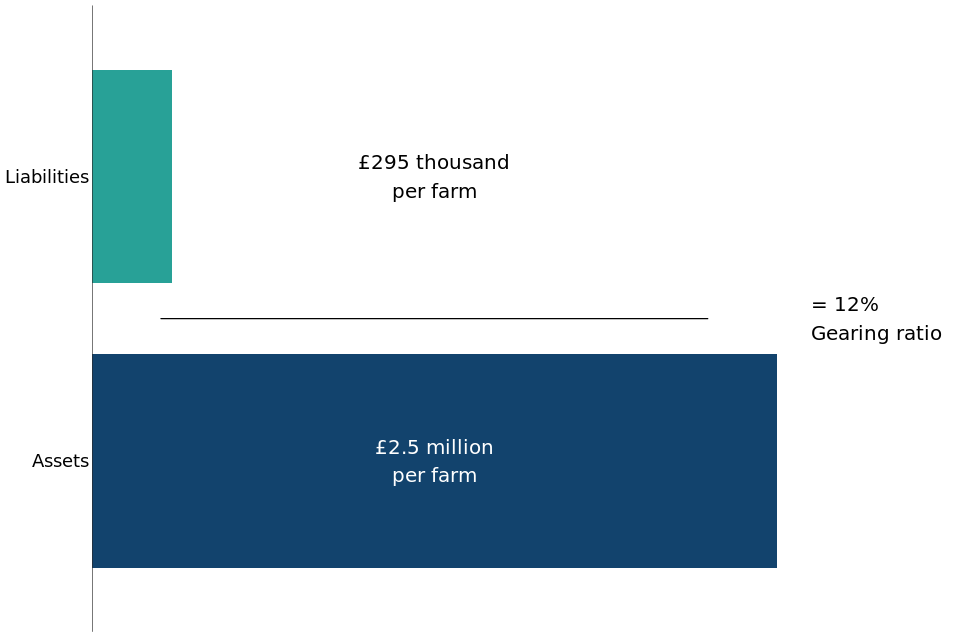

2 Net Worth

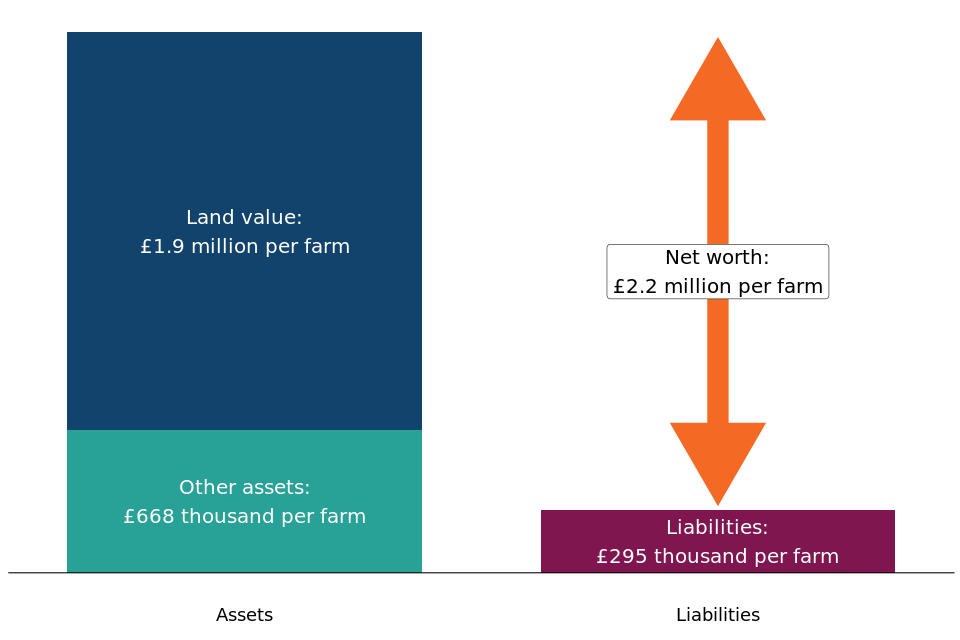

This section examines the net worth of farm businesses in England. Net worth represents the wealth of a farm if all of their liabilities were called in. It is measured by subtracting the value of the total liabilities from total assets, which includes tenant-type capital and land. Farms with a high net worth are more likely to be resilient to changes in their income in the short-term because they can draw on their reserves to support the business if the financial position of the farm deteriorates.

Figure 2.1 Net worth calculation for farms in England, 2022/23

Figure 2.1 shows how net worth is calculated, along with the associated figures at the all farm level for 2022/23. The average net worth across all farms in England was £2.2 million in 2022/23. Figure 2.1 of the 2021/22 publication shows the figures from the previous survey year. Compared with 2021/22, in 2022/23 the number of farms with a net worth of at least £1.5 million increased by 6 percentage points to 49%.

Figure 2.2 Average net worth in current (nominal) values and real terms (2022/23 prices) in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. Real terms prices use the latest GDP deflator data, published 22 December 2023 at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/timeseries/ybgb.

2. The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average liabilities have been calculated using both methods for comparability.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 2.2 shows a time series of average net worth per farm in both current and real terms. There has been a general increase in both current prices and real terms since 2009/10, with a slight dip in the real terms values between 2018/19 and 2020/21. While the nominal value rose by 6% to £2.2 million in 2022/23, in real terms, average net worth marginally fell.

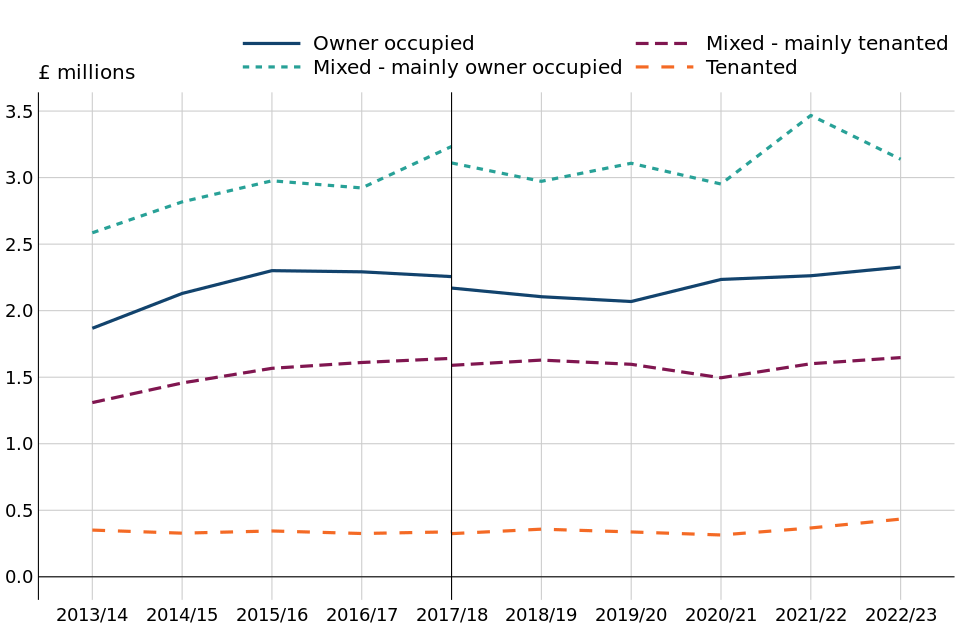

Figure 2.3 Average net worth in real terms (2022/23 prices) by farm tenure in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure note: The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average net worth has been calculated using both methods for comparability.

The data for this chart also includes current (nominal) terms values and breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 2.3 shows a time series of average net worth in real terms by tenure type. In general, farms with greater land ownership tend to have a greater net worth, demonstrating the important contribution of land value to net worth. The average net worth for all tenure types increased by at least 20% overall between 2013/14 and 2022/23.

Farms that were mixed but mainly owner occupied had the highest average net worth in 2022/23, £3.1 million. However, these farms were the only tenure type to see their average net worth fall compared to 2021/22; it fell by 9%. The lowest average net worth was in tenanted farms at £434 thousand, but these farms also saw the largest percentage increase, 18%, between 2021/22 and 2022/23.

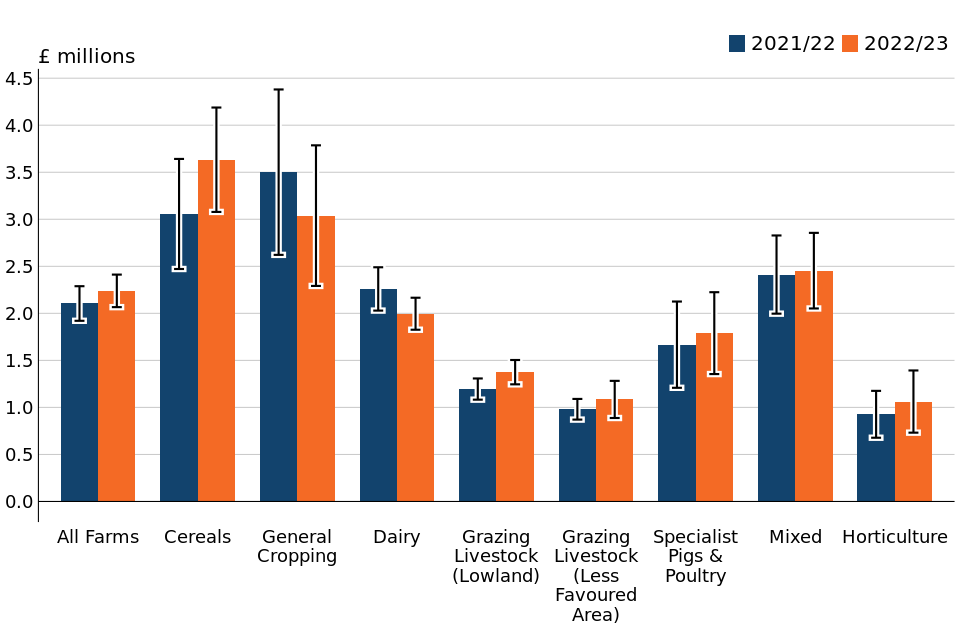

Figure 2.4 Average net worth by farm type in England, 2021/22 and 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart includes a full time series, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 2.4 shows average net worth per farm, by farm type in, 2021/22 and 2022/23. Continuing a trend over several years, cereal and general cropping farms had the highest average net worth of all farm types, at £3.6 million and £3.0 million respectively. The lowest net worth was seen in horticulture farms, with an average net worth of £1.1 million.

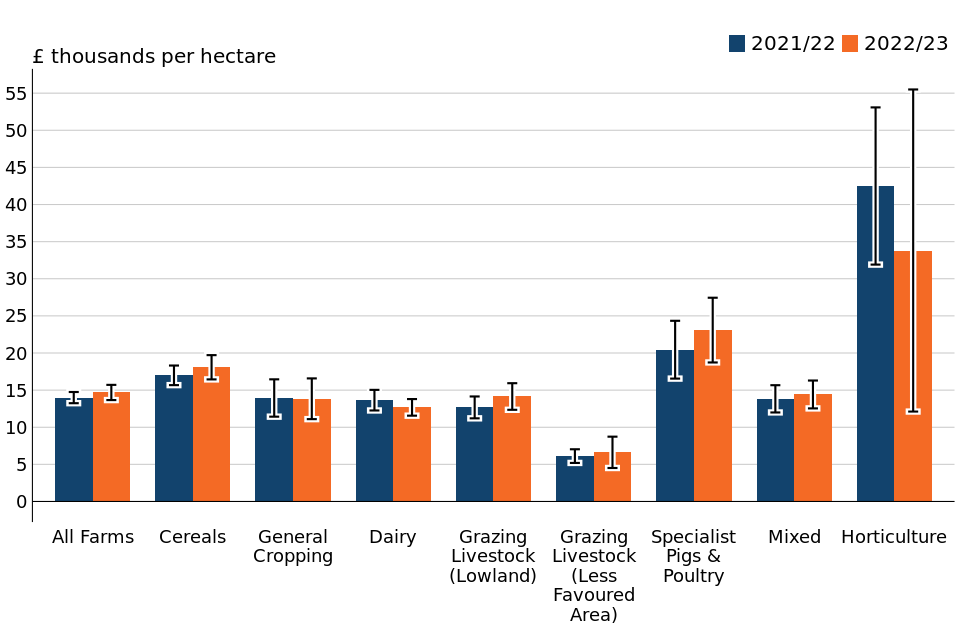

Figure 2.5 Average net worth per hectare of farmed land by farm type in England, 2021/22 and 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart includes a full time series, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 2.5 shows average net worth per hectare by farm type in 2021/22 and 2022/23. While they had the highest average net worth overall, cereal farms had an average net worth per hectare of £18 thousand. Conversely, the net worth per hectare of horticulture farms was the highest by far, at £34 thousand per hectare. This is largely because, in general, horticulture farms farm on a much smaller area than other farm types but are growing higher value crops such as salad vegetables or mushrooms. The second highest net worth per hectare value was in specialist pig and poultry farms, at £23 thousand per hectare. This is likely because buildings which house animals are not included as part of the farmed area; pig and poultry farms are more likely to keep animals housed, resulting in a higher per hectare value. The farm type with the lowest average net worth per hectare was LFA grazing livestock farms, at £7 thousand per hectare.

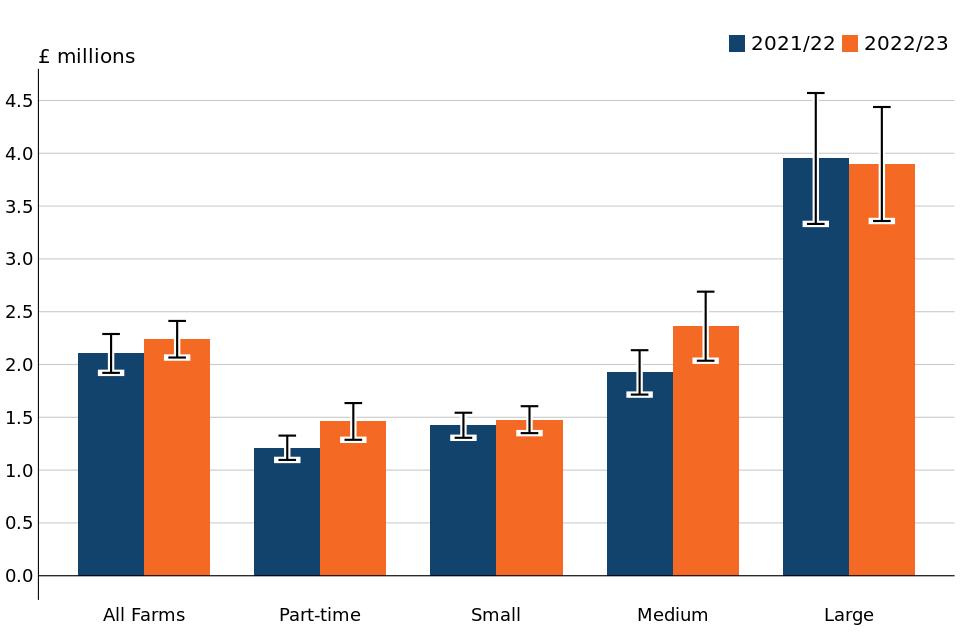

Figure 2.6 Average net worth by farm business size (based on SLR) in England, 2021/22 and 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart includes a full time series, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 2.6 shows average net worth per farm, by farm business size, in 2021/22 and 2022/23. The average net worth of farms increases with farm business size; in 2022/23, the lowest average net worth was in part-time farm businesses, at £1.5 million, and the highest average net worth was in large farm businesses, at £3.9 million.

Figure 2.7 Distribution of farms by net worth and farm business size (based on SLR) in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

The proportion of farms with a net worth of at least £1.5 million generally increases with the size of the farm business, from 37% in small farm businesses to 67% in large farm businesses. Conversely, as the farm businesses increase in size, the proportion of farms with a net worth of less than £250 thousand decreases, with large farm businesses at 3% and part-time farm businesses at 14%.

3 Gearing ratio

In order to get a deeper understanding of the indebtedness of a farm, we can compare what the farm business owes (its liabilities) to the assets that the owners have tied up in the business. An accounting measure is used which expresses a farm’s liabilities as a proportion of its assets, sometimes referred to as the gearing ratio. Figure 3.1 illustrates how gearing ratio is calculated.

Figure 3.1 Gearing ratio calculation for farms in England, 2022/23

If a farm has assets equal to its liabilities, this will give a gearing ratio value of 100%, whereas if their assets are twice as large as its liabilities then the gearing ratio will be 50%. This provides a measure of the long-term financial viability of a farm. A lower ratio is generally seen as more acceptable because this suggests that the farm business is more likely to be able to meet its investment needs from earnings. A higher ratio may be seen as a greater risk because interest costs will be higher, and the farm will have lower funds to borrow against. However, being highly geared does not necessarily imply an unsuccessful business. Investment can increase profitability, so increasing the gearing ratio can lead to better performance. In 2022/23, the average gearing ratio for farms in England was 12%, meaning that, generally speaking, farms in England have large assets relative to their liabilities.

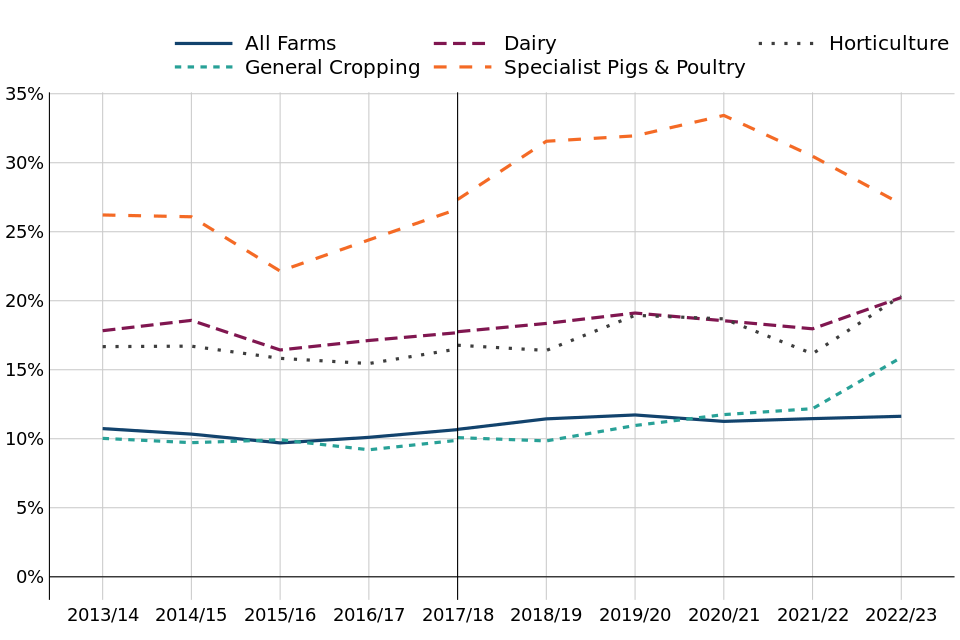

Figure 3.2 Average gearing ratio by farm type (all farms and selected types) in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average gearing ratio has been calculated using both methods for comparability.

2. Farm types are included in the graph if their average gearing ratio changed by at least 2 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 3.2 shows a time series of average gearing ratio for all farms, as well as any farm types which saw a change to their average gearing ratio of at least 2 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23. The average gearing ratio for all farms has had very little variation over the years, fluctuating between 10% and 12%.

In 2022/23, the farm type with the highest average gearing ratio continued to be specialist pig and poultry farms, with a ratio of 27%. The specialist pig and poultry farms also had the biggest change compared to the previous year, a fall of 3 percentage points. The second highest average gearing ratio was 20%, seen in both horticulture and dairy farms. For the third consecutive year, cereal farms had the lowest average gearing ratio in 2022/23, at 7%.

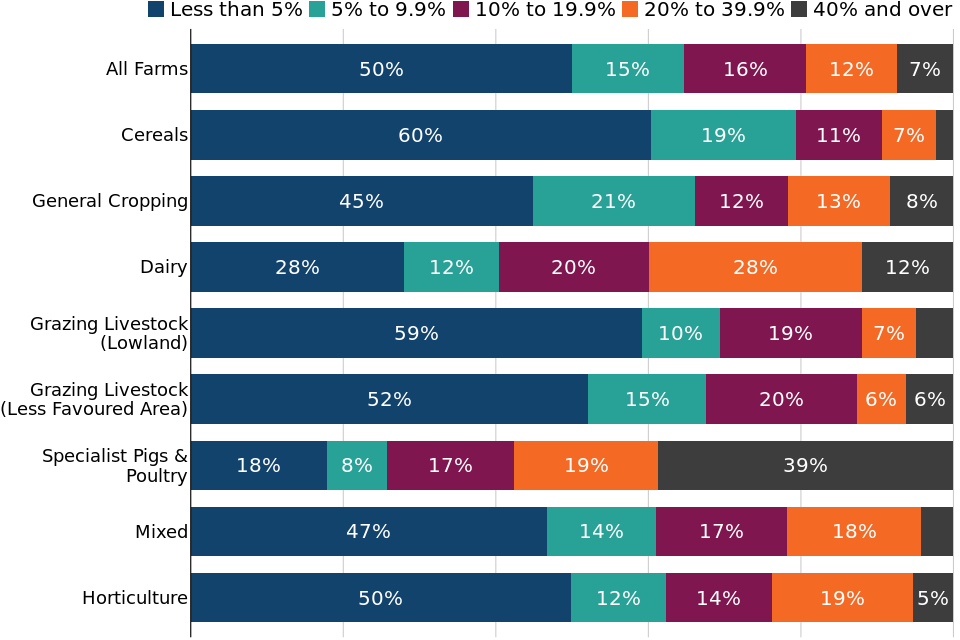

Figure 3.3 Distribution of farms by gearing ratio and farm type in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 3.3 compares the distribution of gearing ratio within farm types in 2022/23. Most farms had a relatively low value, with half of all farms having a gearing ratio of less than 5%. Just 7% of farms had a gearing ratio of at least 40%.

Between farm types, the percentage of farms with a gearing ratio of less than 5% ranged from 18% of specialist pig and poultry farms to 60% of cereal farms. The percentage of farms with a gearing ratio of 40% or over ranged from 2% of cereal farms to 39% of specialist pig and poultry farms.

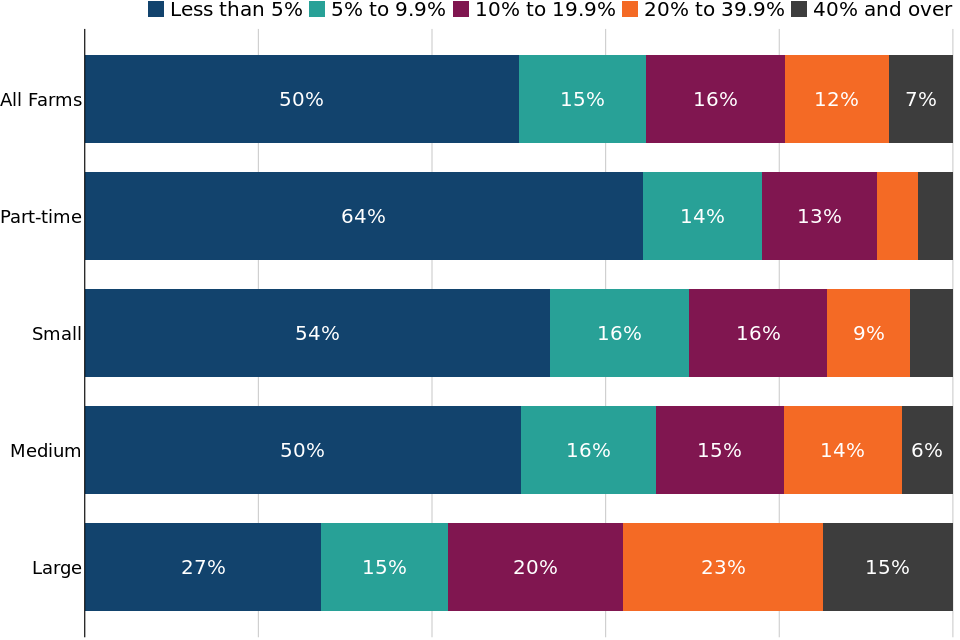

Figure 3.4 Distribution of farms by gearing ratio and farm business size (based on SLR) in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Average gearing ratio increased with farm business size, ranging from 7% of medium farms to 16% of large farms. For all farm business sizes, average gearing ratio was similar to the 2021/22 figures.

Figure 3.4 shows the distributions of gearing ratio for farms of different sizes (based on SLR) in 2022/23. Around two thirds of part-time farms had a gearing ratio of less than 5%, and 4% of them had a gearing ratio of at least 40%. Conversely, 27% of large farms had a gearing ratio of less than 5%, and 15% had a gearing ratio of 40% or more. This was driven by larger farms having more liabilities (Figure 1.6) rather than them having fewer assets.

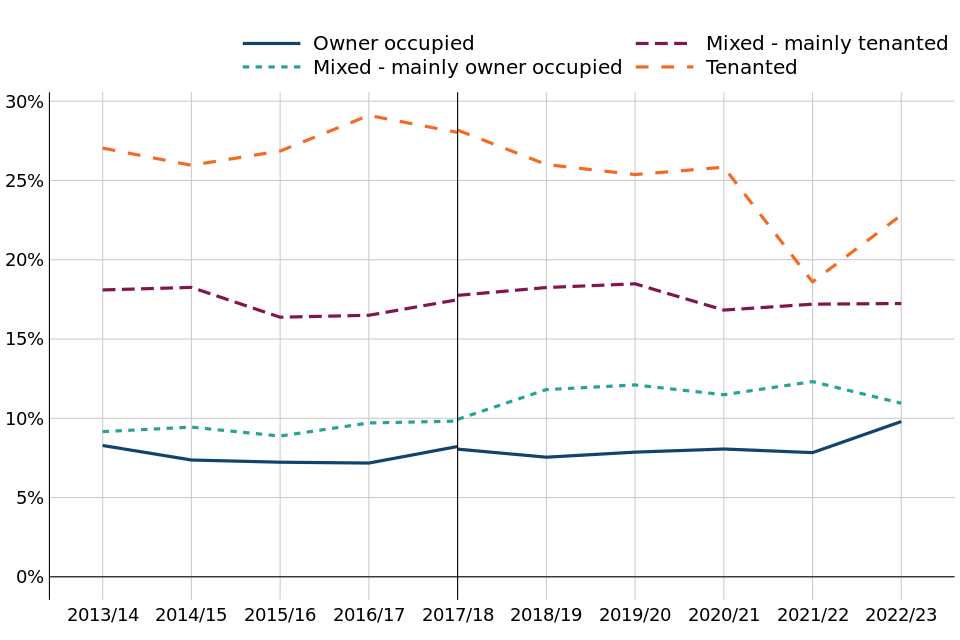

Figure 3.5 Average gearing ratio by farm tenure in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure note: The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average gearing ratio has been calculated using both methods for comparability.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 3.5 shows the average gearing ratio per farm, by tenure type, over the last ten years. The gearing ratio consistently reduces as the level of land ownership increases, with the average gearing ratio of tenanted farms at 23% and the average for owner occupied farms at 10% in 2022/23.

3.1 Gearing ratio by liabilities and net worth

Farms with lower liabilities also tended to have a lower gearing ratio; of farms with less than £10 thousand in liabilities, almost all had a gearing ratio of less than 5%. This indicates that these farms were in a favourable situation, because they had very low liabilities compared to their assets. On the other hand, 29% of farms with at least £400 thousand of liabilities had a gearing ratio of over 40%. However, as previously mentioned, a high gearing ratio alone is not necessarily a marker of a less successful business.

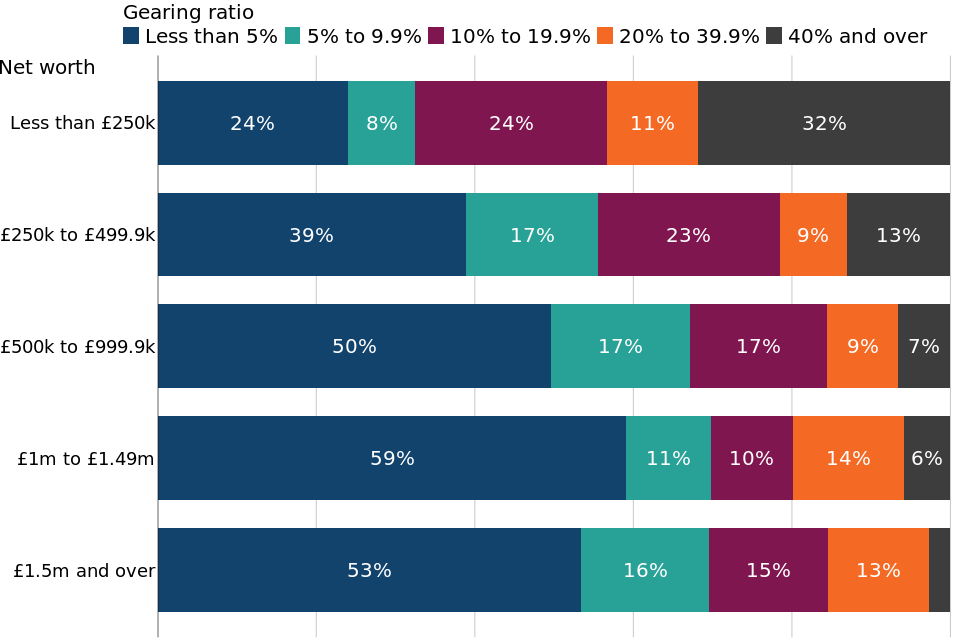

Figure 3.6 Distribution of farms by gearing ratio and net worth in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 3.6 shows the distribution of farms by gearing ratio and net worth. Farms with a higher net worth also tended to have a lower gearing ratio. Of farms with a net worth of less than £250 thousand, around a quarter had a gearing ratio of less than 5%, while around a third had a gearing ratio of 40% or more. In comparison, just over half of farms with a net worth of at least £1.5 million had a gearing ratio of less than 5%, and 3% had a gearing ratio of 40% or more.

4 Liquidity

Liquidity is a measure of the short-term financial viability of farms. A large proportion of the assets of a farm, such as land or machinery, will typically have a monetary value that is difficult or costly to realise in the short term. The liquidity ratio provides an indication of the ability of a farm to finance its immediate financial demands, known as ‘current liabilities’, from its assets that can be realised easily, such as cash, savings or stock, known as ‘current assets’. If the liquidity ratio is equal to or above 100%, then a farm is able to meet its current liabilities using current assets. If the ratio is less than 100%, then a farm is unable to meet its immediate financial demands using current assets. Figure 4.1 illustrates how liquidity ratio is calculated.

Figure 4.1 Liquidity ratio calculation for farms in England, 2022/23

In 2022/23, the average liquidity ratio was 321%, meaning that, in general, farms in England were able to meet their current liabilities.

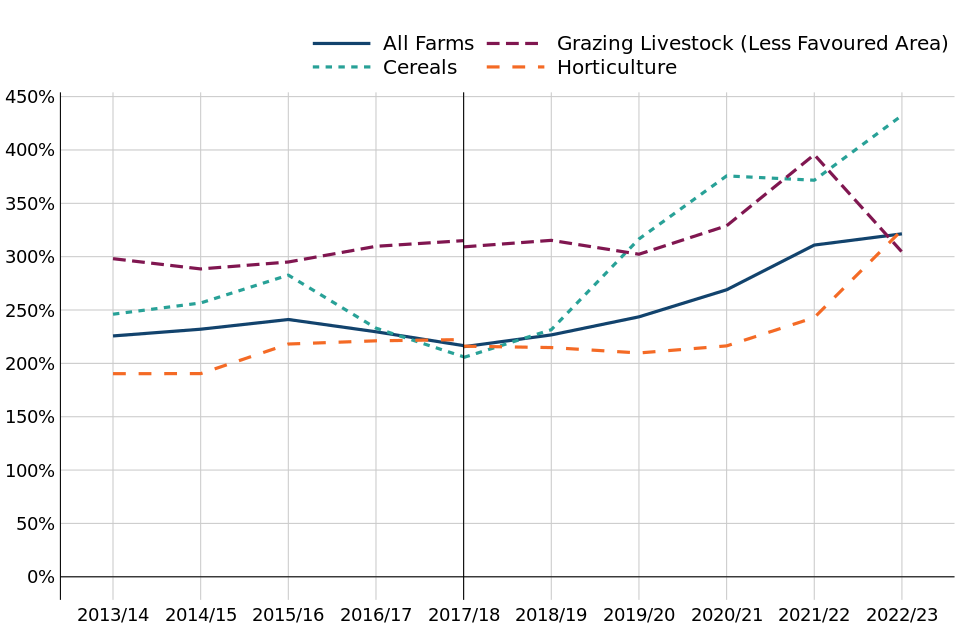

Figure 4.2 Average liquidity ratio of selected farm types in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average liquidity ratio has been calculated using both methods for comparability.

2. Farm types are included in the graph if their average liquidity ratio changed by at least 50 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 4.2 shows the average liquidity ratio for all farms between 2013/14 and 2022/23, as well as any farm types whose average liquidity ratio changed by at least 50 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23. The average liquidity ratio of farm businesses in England increased for the fifth consecutive year in 2022/23.

In 2022/23, cereal farms had the highest average liquidity ratio, at 432%, whereas dairy has the lowest, 195%.

The largest increase compared to the previous year was seen in horticulture farms, which rose by 82 percentage points, and the smallest increase was in mixed farms, which rose by 27 percentage points. Other farm types saw their average liquidity ratio fall, with the biggest decrease seen in LFA grazing livestock farms, which fell by 91 percentage points.

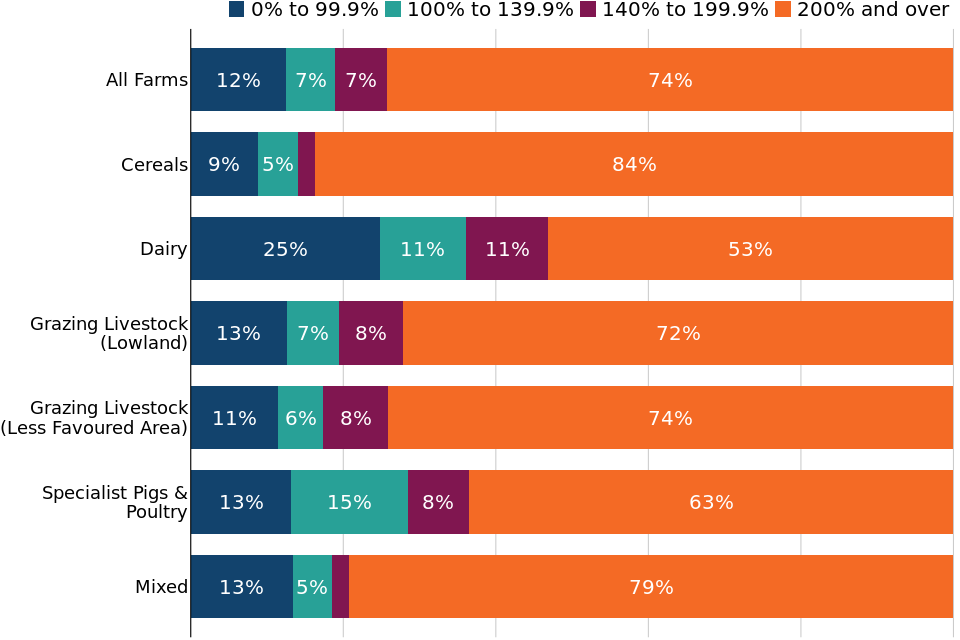

Figure 4.3 Distribution of farms by liquidity ratio and farm type in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

3. Due to small sample sizes, the distributions for horticulture and general cropping farms are not included in this chart.

The data for this chart includes a more detailed breakdown, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 4.3 compares the distribution of liquidity ratio within farm types in 2022/23. The majority of farms had a strong liquidity ratio; around three quarters had a ratio of at least 200%, suggesting that they could easily cover their immediate financial demands with their current assets. Overall, 12% of farms had a liquidity ratio below 100%; this is the point at which current assets do not cover liabilities. When broken down by farm type, dairy farms were most likely to be in this situation, with a quarter of these farms having a liquidity ratio of less than 100%.

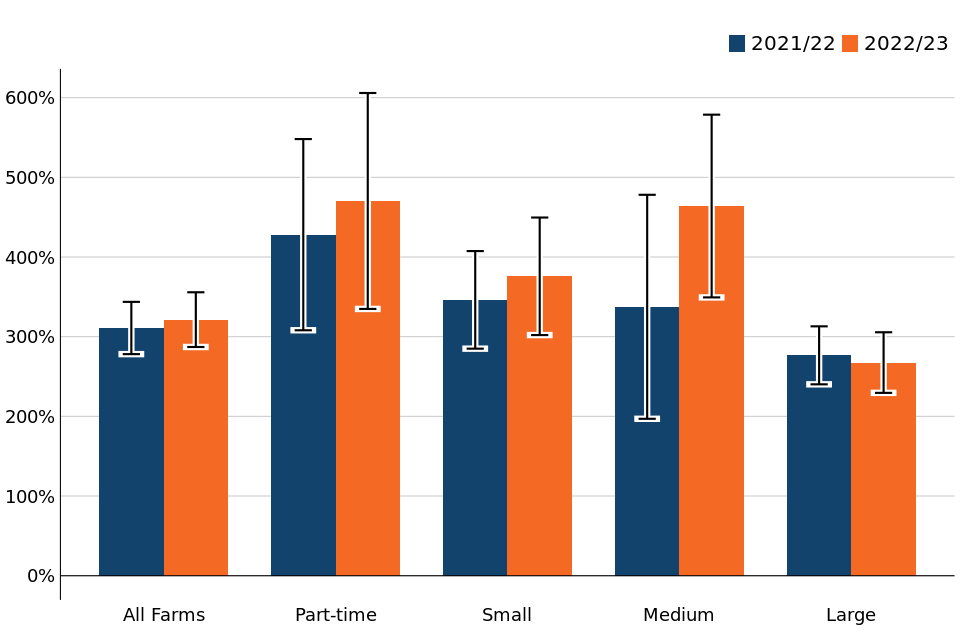

Figure 4.4 Average liquidity ratio by farm business size (based on SLR) in England, 2021/22 and 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 4.4 shows the average liquidity ratio of farms in England by farm business size, based on SLR, in 2021/22 and 2022/23. Large farm businesses had the lowest average ratio, 268%, while part-time farm businesses had the highest average ratio, 470%. Medium farm businesses were a very close second and also increased the most compared to the previous year, increasing by 126 percentage points to 464%.

The highest percentage of farms with a liquidity ratio under 100% was seen in large farm businesses; 17% of these farms did not have enough in current assets to cover their liabilities. The smallest percentage was in part-time farm businesses, at 8%.

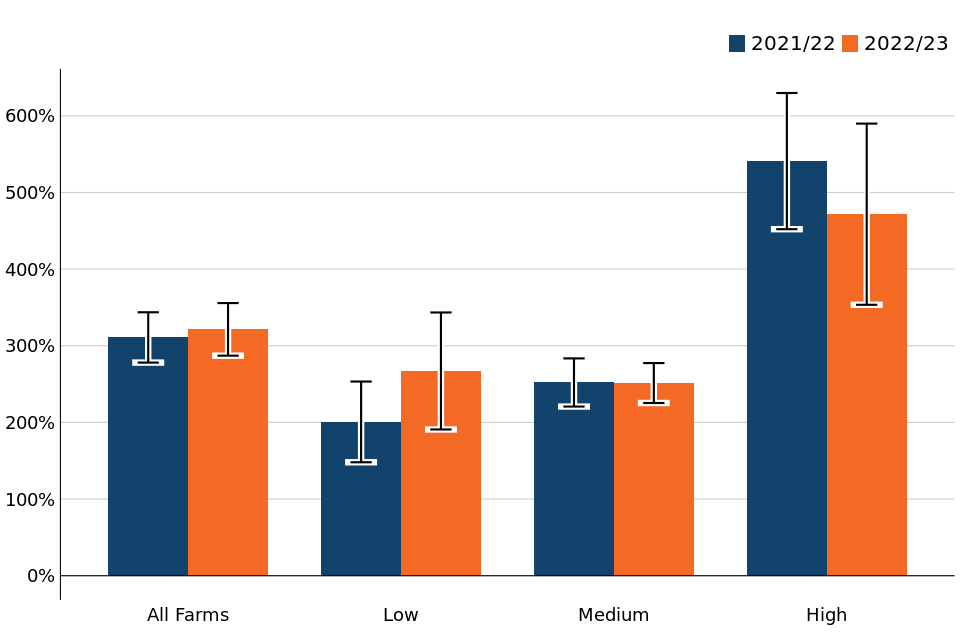

Figure 4.5 Average liquidity ratio by economic performance in England, 2021/22 and 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 4.5 shows the average liquidity ratio for farms in England, split by economic performance band into the bottom 25%, middle 50% and top 25% of performers; these bands are labelled as ‘Low’, ‘Medium’ and ‘High’ respectively. Farms who were in the top 25% of economic performers had the highest average liquidity ratio in 2022/23, at 472%, which was 69 percentage points lower than the 2021/22 value. In contrast, the average liquidity ratio of farms in the bottom 25% of economic performers rose by 66 percentage points to 267% over the same period.

When comparing the distribution of liquidity ratio by economic performance band, 15% of medium performing farms had a liquidity ratio below 100% in 2022/23, while just 5% of high performing farms did.

5 Net Interest payments as a proportion of Farm Business Income (FBI)

This section examines net interest payments as a proportion of FBI. This measure provides an indication of whether farms can afford to pay the interest on their debts. The usual measure of FBI includes net interest payments as a cost, therefore, the value for FBI used in the calculation of this measure has not had net interest deducted from it.

Figure 5.1 Net interest as a proportion of FBI calculation for farms in England, 2022/23

In 2022/23, net interest payments were 8% of the average farm’s FBI. This was a rise of 2 percentage points compared with 2021/22.

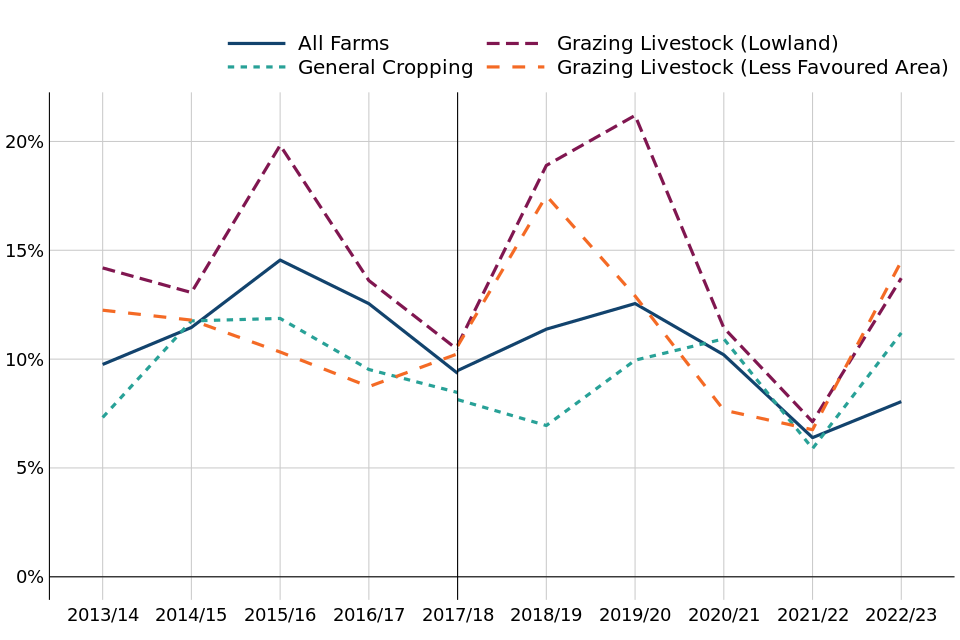

Figure 5.2 Average net interest payments as a proportion of Farm Business Income of selected farm types in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average liquidity ratio has been calculated using both methods for comparability.

2. Farm types are included in the graph if their average net interest proportion changed by at least 5 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 5.2 shows the average net interest payments as a proportion of FBI for all farms between 2013/14 and 2022/23, as well as any farm types whose net interest payments changed by at least 5 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23. All sectors except for dairy saw increase in their average proportion of net interest payments.

In 2022/23, specialist pig and poultry had the highest net interest proportion, at 17%. The lowest proportion was 4%, seen in cereal farms.

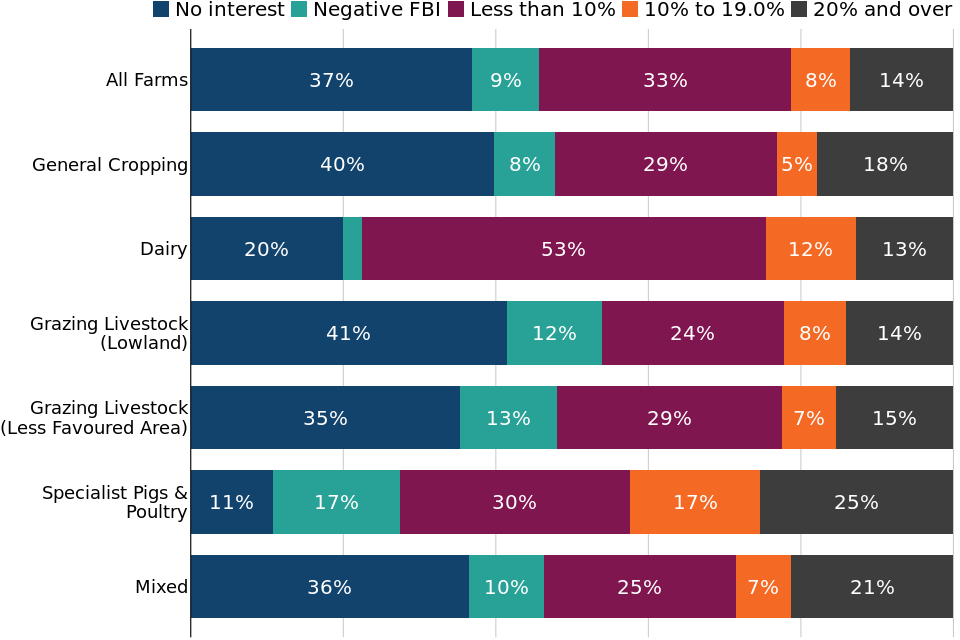

Figure 5.3 Distribution of farms by net interest payments as a proportion of Farm Business Income and farm type in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

3. Due to small sample sizes, the distributions for horticulture and cereal farms are not included in this chart.

The data for this chart includes a more detailed breakdown, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 5.3 compares the distribution of net interest payment proportions within farm types in 2022/23. Overall, 37% of farm businesses either paid no interest (in other words, they had no loans) or the interest they received on their savings or investments was greater than the interest paid on loans. The horticulture sector had just over half of farms in this group, compared to just 11% of specialist pig and poultry farms. The farm type which had the highest percentage of farms which already had a negative FBI (before interest payments) was specialist pig and poultry farms, at 17%; these farms would have been unable to pay some or all of the interest on their debts without further borrowing or drawing on their assets. Specialist pig and poultry farms also had the highest proportion or farms, 25%, paying net interest equivalent to 20% or more of their FBI.

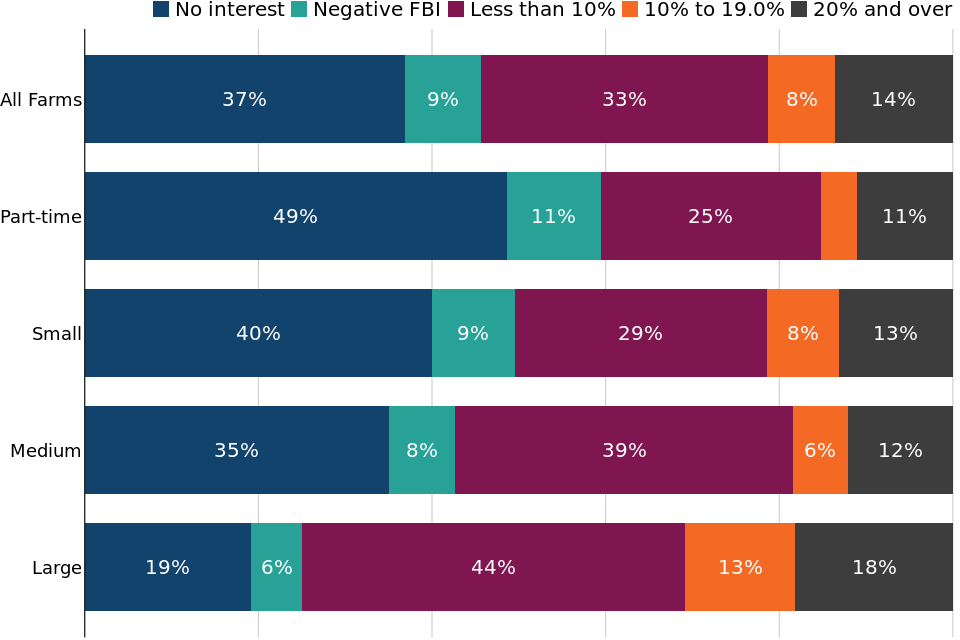

Figure 5.4 Distribution of farms by net interest payments as a proportion of Farm Business Income and farm business size (based on SLR) in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

The data for this chart includes a more detailed breakdown, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 5.4 shows the distributions of net interest proportions for farms in England by farm business size (based on SLR) in 2022/23. As the size of the farm business increased, the percentage of farms who either paid no interest or received more in interest than they paid decreased. For part-time farms, just under half of farm businesses were in this situation, whereas 19% of large farms were. The differences between farm business sizes in the percentage of farms paying net interest equivalent to more than 20% of their FBI was less pronounced, with values ranging from 11% of part-time farms to 18% of large farms.

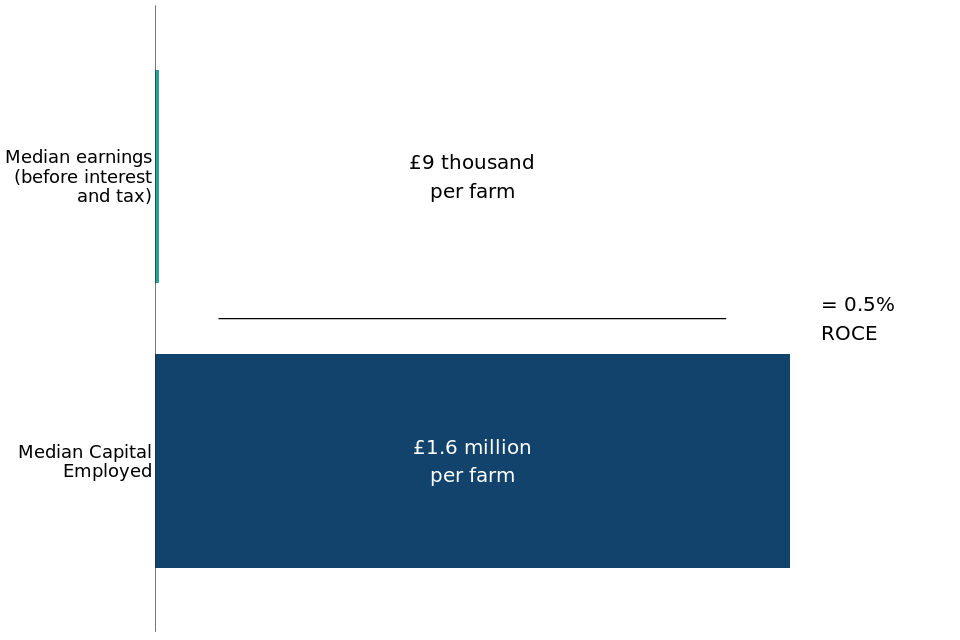

6 Return on Capital Employed

Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) is a measure of the return that a business makes from its available capital. ROCE provides a more holistic view than profit margins, focusing on efficient use of capital and low costs, allowing an equal comparison across farms of differing sizes. A positive ROCE value indicates that a farm is achieving an economic return on the capital used, while a negative ROCE value indicates that a farm is not achieving an economic return on the capital employed.

The ROCE calculation uses earnings (before interest and tax) and Capital Employed. Earnings are calculated by subtracting the imputed cost of all unpaid labour from Farm Business Income (FBI). Capital Employed is the available amount that each farm could use to earn profit in the upcoming financial year, and is calculated by subtracting current (short-term) liabilities from total assets. ROCE is calculated as earnings (before interest and tax) divided by Capital Employed.

Given the importance of land as an asset base for farming, an additional measure of ROCE has been included which excludes the value of land from assets.

All of the previous measures discussed in this release describes average values using the mean. However, the distribution of the ROCE values is highly skewed and as a result, the average of the ROCE is most appropriately described using the median.

Figure 6.1 Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) calculation for farms in England, 2022/23

In 2022/23, the median ROCE per farm in England was 0.5%.

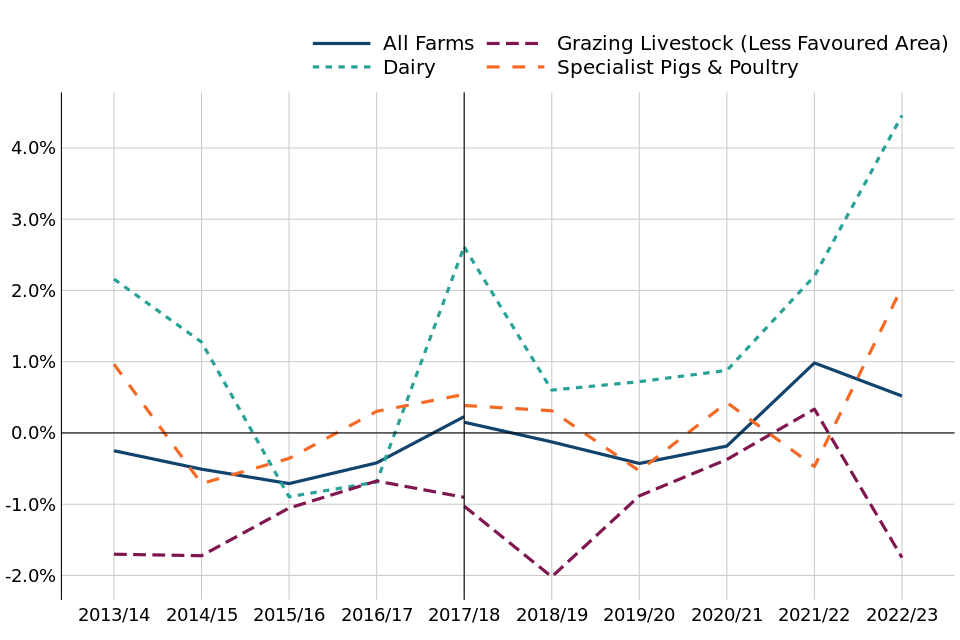

Figure 6.2 Average (median) Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) of selected farm types in England, 2013/14 to 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The break in the series shown in 2017/18 represents changes in the method used to assign farms to a specific farm type. Where breaks occur, average liquidity ratio has been calculated using both methods for comparability.

2. Farm types are included in the graph if their average ROCE changed by at least 2 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23.

The data for this chart also includes breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 6.2 shows the time series of average (median) ROCE for all farms in England, as well as any farms whose ROCE changed by at least 2 percentage points between 2021/22 and 2022/23. In 2022/23, average ROCE experienced a fall of 0.5 percentage points to 0.5%, which was driven by a reduction in earnings along with an increase in Capital Employed. The highest ROCE was seen in dairy farms, with a return of 4.5%. The average ROCE values of mixed, lowland grazing livestock, LFA grazing livestock and horticulture farms were negative (-0.6%, -1.4%, -1.7% and -2.2% respectively), indicating that these businesses were not achieving an economic return from their available capital.

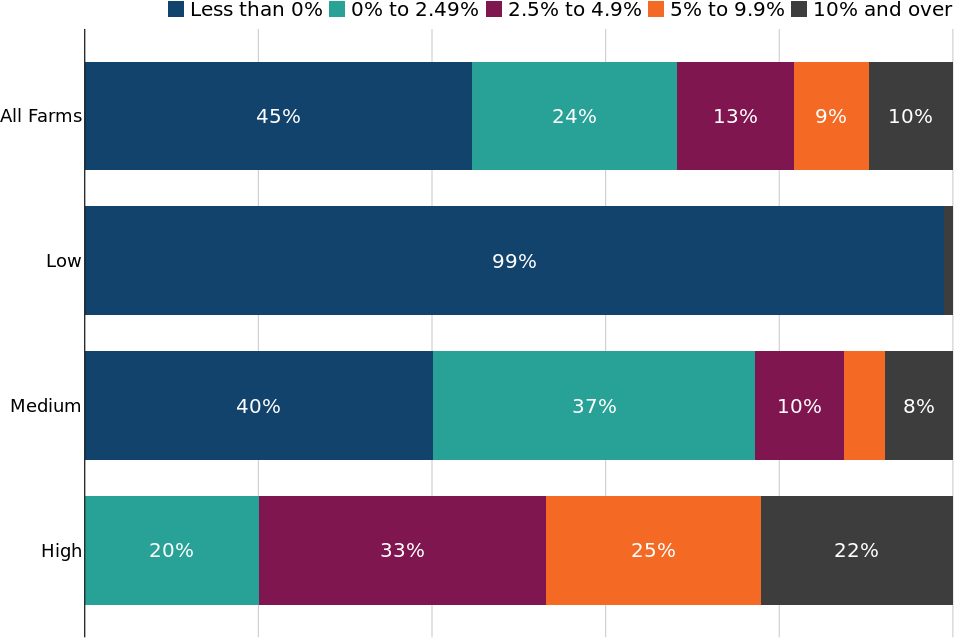

Figure 6.3 Distribution of farms by Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) and economic performance in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Text is not displayed where proportions are below 5%.

The data for this chart includes a more detailed breakdown, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 6.3 shows the distributions of net interest proportions for farms in England by economic performance in 2022/23. Economic performance bands split farms into the bottom 25%, middle 50% and top 25% of performers; these bands are labelled as ‘Low’, ‘Medium’ and ‘High’ respectively.

Overall, 45% of farms had a negative ROCE in 2022/23, and 10% had a ROCE of over 10%. As in previous years, no high performing farms had negative ROCE, which was in stark contrast with low performing farms where almost all of the farms sampled by the Farm Business Survey had a negative ROCE. For the top 25% of economic performers, 22% of the farms had a ROCE of over 10%.

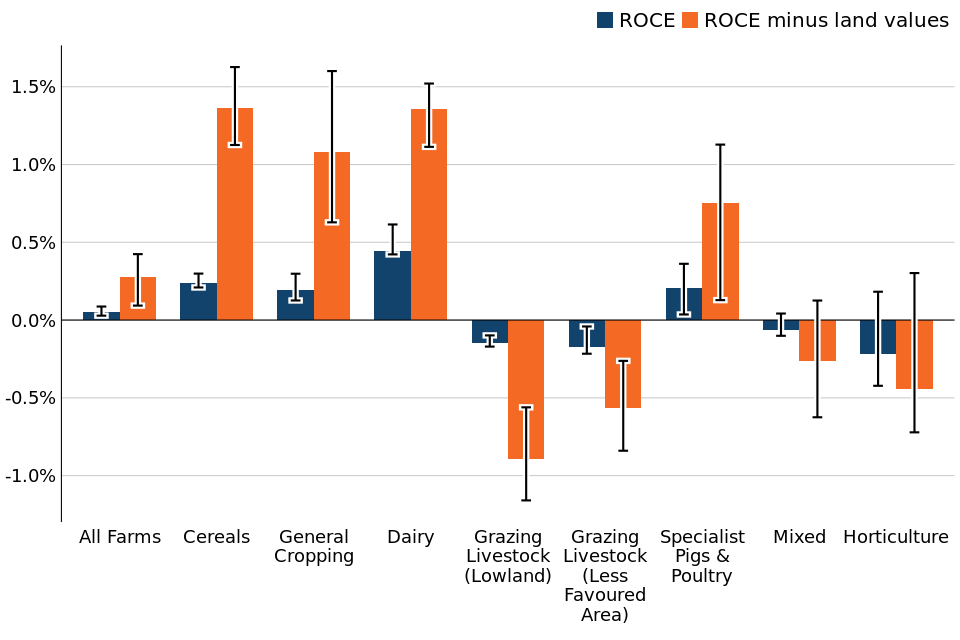

Figure 6.4 Average (median) Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) and ROCE minus land values by farm type in England, 2022/23

Figure notes:

1. The legend is presented in the same order as the bars.

2. Values are shown here with 95% confidence intervals, which give an indication of the degree of uncertainty around an estimate; the lower and upper limits show the possible range around the published averages.

The data for this chart includes a full time series, as well as breakdowns by other factors:

View the data for this chart

Download the data for this chart

Figure 6.4 compares the 2022/23 averages (median) of ROCE and average ROCE minus land values for each farm type. The ROCE averages were consistently closer to zero than the ROCE minus land values averages, demonstrating the importance of land as an asset base for farming.

7 What you need to know about this release

7.1 Contact details

Responsible statistician: Cat Hand

Public enquiries: [email protected]

For media queries between 9am and 6pm on weekdays:

Telephone: 0330 041 6560

Email: [email protected]

7.2 National Statistics Status

Accredited official statistics are called National Statistics in the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007. An explanation can be found on the Office for Statistics Regulation website. Our statistical practice is regulated by the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR). OSR sets the standards of trustworthiness, quality and value in the Code of Practice for Statistics that all producers of official statistics should adhere to.

These accredited official statistics were independently reviewed by the Office for Statistics Regulation in January 2014. They comply with the standards of trustworthiness, quality and value in the Code of Practice for Statistics and should be labelled ‘accredited official statistics’.

You are welcome to contact us directly with any comments about how we meet these standards (see contact details above). Alternatively, you can contact OSR by emailing [email protected] or via the OSR website.

Since the latest review by the Office for Statistics Regulation, we have continued to comply with the Code of Practice for Statistics, and have made the following improvements:

-

Reviewed and improved data presentation to better meet accessibility guidelines

-

Automated production of the statistics using Reproducible Analytical Pipelines (RAP)

-

Reviewed and improved accompanying commentary.

7.3 User engagement

As part of our ongoing commitment to compliance with the Code of Practice for Official Statistics we wish to strengthen our engagement with users of these statistics and better understand the use made of them and the types of decisions that they inform.

We invite users to make contact to advise us of the use they do, or might, make of these statistics, and what their wishes are in terms of engagement. Feedback on this statistical release and enquiries about these statistics are also welcome.

7.4 Survey content, methodology and data uses

The Farm Business Survey is an annual survey providing information on the financial position, physical characteristics, and economic performance of farm businesses in England. The sample of farm businesses covers all regions of England and all types of farming.

Data for the Farm Business Survey are collected through face-to-face interviews with farmers, conducted by highly trained research officers.

The data are widely used by the industry for benchmarking and inform wider research into the economic performance of the agricultural industry, as well as for evaluating and monitoring current policies. The data will also help to monitor farm businesses throughout the Agricultural Transition period.

7.5 Availability of results

All Defra statistical notices can be viewed on the Statistics at Defra page.

More publications and results from the Farm Business Survey are available on the Farm Business Survey Collection page.

8 Technical note

8.1 Survey coverage and weighting

The Farm Business Survey only includes farm businesses with a Standard Output of at least 25 thousand Euros, based on activity recorded in the previous June Survey of Agriculture and Horticulture. In 2022/23, the sample of 1,359 farms represented approximately 52,500 farm businesses in England.

Initial weights are applied to the Farm Business Survey records based on the inverse sampling fraction for each design stratum (farm type and farm size). Dataset table 16 from the Farm Accounts in England publication shows the distribution of the sample compared with the distribution of businesses from the 2022 June Survey of Agriculture. These initial weights are then adjusted, using calibration weighting, so that they can produce unbiased estimates of a number of different target variables. More detailed information about the Farm Business Survey can be found on the technical notes and guidance page. This includes information on the data collected, information on calibration weighting and definitions used within the Farm Business Survey.

The data used for this analysis is from those farms present in the Farm Business Survey that have complete returns on their assets and liabilities. In 2022/23 this subsample consisted of 1,344 farms (99% of the full sample). This subsample has been reweighted using a method that preserves marginal totals for populations according to farm type and farm size groups. As such, values shown in this publication may not exactly match results calculated using the main FBS weights.

8.2 Accuracy and reliability of the results

It is not logistically feasible to survey the entire population of farms, therefore, the published figures from the Farm Business Survey are subject to sampling error. This is a fundamental premise of conducting statistical surveys, which by design aim to capture a representative sample of the underlying population through various sampling techniques.

The representation of data in this publication attempts to account for this sampling error by providing 95% confidence intervals as a measure of uncertainty for the estimated mean. This is provided through error bars in the bar plots.

Narrower confidence intervals generally reflect larger sample sizes and greater homogeneity within the group and are thus ‘more precise’ of an indicator for where the true population mean may reside. Conversely, wider confidence intervals are generally characterised by smaller sample sizes and greater sample standard deviations, which are thus ‘less precise’. These estimates should be treated with caution.

A confidence interval is therefore a plausible range of values wherein the true underlying population mean lies within, based on the sample data it draws from. A 95% confidence interval hence refers to the interval in which there is a 95% probability that our true population mean resides.

For the Farm Business Survey, the confidence intervals shown are appropriate for comparing groups within the same year only; they should not be used for comparing with previous years, since they do not allow for the fact that many of the same farms will have contributed to the Farm Business Survey in multiple years. Confidence intervals only give an indication of the sampling error; they do not reflect any other sources of survey errors, such as non-response bias.

8.3 Statistical methods

For each of the sections in this publication, various breakdowns are shown in each sector. In order to determine which breakdowns to include, generalised linear models were fitted to examine which of five predictive variables (farm type, size, tenure type, region and economic performance) were related to each of the response variables of interest (liability, gearing ratio, liquidity ratio, interest payments as a proportion of FBI, and ROCE). In each case the distribution of the response variable was examined and, if necessary, transformed to conform to assumptions of normality. Where a binomial response variable was used (for example, farms having a liquidity ratio of either less than 100% or 100% and over) a binomial-based generalised linear model was fitted using a binomial error distribution and a logit link. The significance of each of the predictive variable were examined and used to inform the breakdowns displayed in this publication. All breakdowns of each variable are available in the underlying data.

8.4 Definitions

Mean

The mean is found by adding up the weighted variable of interest (for example, total liabilities) for each individual farm in the sample for analysis and dividing the result by the corresponding weighted number of farms. In this report, average is usually taken to refer to the mean, except for Return on Capital Employed averages.

Median

The median divides the population, when ranked by an output variable, into two equal sized groups. The median of the whole population is the middle value. In this report, the Return on Capital Employed averages are represented with medians.

Farm type

Where reference is made to the type of farm in this document, this refers to the ‘robust type’, which is a standardised farm classification system. For this publication, pigs and poultry have been merged into a single farm type category.

Farm business size

Farm business sizes are based on the estimated labour requirements for the business, rather than its land area. The farm business size bands used within the detailed results tables which accompany this publication are shown in the table below. Standard Labour Requirement (SLR) is defined as the theoretical number of workers required each year to run a business, based on its cropping and livestock activities.

Table 8.1: Farm business size by Standard Labour Requirement (SLR)

| Farm business size | Definition |

|---|---|

| Part-time | Less than 1 SLR |

| Small | 1 to less than 2 SLR |

| Medium | 2 to less than 3 SLR |

| Large | 3 or more SLR |

Farm economic performance

Economic performance for each farm is measured as the ratio between economic output (mainly sales revenue) and inputs (costs). The inputs for this calculation include an adjustment for unpaid manual labour. The higher the ratio, the higher the economic efficiency and performance. The farms are then ranked and allocated to performance bands based on economic performance percentiles:

Table 8.2: Allocation of economic performance bands

| Performance Band | Definition |

|---|---|

| Low | The bottom 25% of economic performers |

| Medium | The middle 50% of performers |

| High | The top 25% of performers |

Assets

Assets include milk and livestock quotas, as well as land, buildings (including the farmhouse), breeding livestock, and machinery and equipment. For tenanted farmers, assets can include farm buildings, cottages, quotas, etcetera, where these are owned by the occupier. Personal possessions (for example, jewellery, furniture, and possibly private cash) are not included.

Net worth

Net worth represents the residual claim or interest of the owner in the business. It is the balance sheet value of assets available to the owner of the business after all other claims against these assets have been met. Net worth takes total liabilities from total assets, including tenant type capital and land. This describes the wealth of a farm if all of their liabilities were called in.

Liabilities

Liabilities are the total debt (short- and long-term) of the farm business including monies owed. It includes mortgages, long-term loans and monies owed for hire purchase, leasing and overdrafts.

Tenant type capital

Tenant type capital comprises assets normally provided by tenants and includes livestock, machinery, crops and produce in store, stocks of bought and home-grown feeding stuffs and fodder, seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, medicines, fuel and other purchased materials, work in progress (tillages or cultivations), cash and other assets needed to run the business. Orchards, other permanent crops, such as soft fruit and hop gardens and glasshouses, are also generally considered to be tenant-type capital.

Return on Capital Employed (ROCE)

Return on capital employed (ROCE) is a measure of the return that a business makes from the available capital. ROCE provides a more holistic view than profit margins, focusing on efficient use of capital and low costs and allowing an equal comparison across farms of differing sizes. It is calculated as economic profit divided by capital employed.

Liquidity ratio

The liquidity ratio shows the ability of a farm to finance its immediate financial demands from its current assets, such as cash, savings or stock. It is calculated as current assets divided by the current liabilities of the farms.

Gearing ratio

The gearing ratio gives a farm’s liabilities as a proportion of its assets.

Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA)

Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA) is the crop area, including fodder, set-aside land, temporary and permanent grass and rough grazing in sole occupation (but not shared rough grazing). In other words, it is the agricultural area of the farm. It includes bare land and forage let out for less than one year.

Farm Business Income (FBI)

Farm Business Income (FBI) for sole traders and partnerships represents the financial return to all unpaid labour (farmers and spouses, non-principal partners and directors and their spouses and family workers) and on all their capital invested in the farm business, including land and buildings. For corporate businesses it represents the financial return on the shareholders capital invested in the farm business. Note that prior to 2008/09 directors remuneration was not deducted in the calculation of farm business income.

Farm Business Income is used when assessing the impact of new policies or regulations on the individual farm business. Although Farm Business Income is equivalent to financial Net Profit, in practice the measures are likely to differ because Net Profit is derived from financial accounting principles whereas Farm Business Income is derived from management accounting principles. For example, in financial accounting output stocks are usually valued at cost of production, whereas in management accounting they are usually valued at market price. In financial accounting depreciation is usually calculated at historic cost whereas in management accounting it is often calculated at replacement cost.