Diversity of the judiciary: Legal professions, new appointments and current post-holders - 2023 Statistics

Updated 8 September 2023

Applies to England and Wales

1. Main Points

1.1 Sex

| Women remain generally well represented in the legal professions and judiciary. | Women constitute 40% of barristers, 53% of solicitors, 77% of Chartered Legal Executives, and 42% of all judges. |

| There is no disparity between women and men in their selection to judicial posts. | Women accounted for 50% of the eligible pool and 51% of recommendations in legal judicial selection exercises. |

1.2 Ethnicity

| There has been a gradual increase in the representation of ethnic minorities in the legal professions and judiciary. | In the last decade, the ethnic minority proportion of barristers increased from 13% to 16%, of solicitors from 15% to 19%, of Chartered Legal Executives from 5% to 11%, and from 7% to 11% for all judges. |

| There is no evidence of disparity for ethnic minority candidates in legal judicial selection exercises. | Across all legal exercises in 2022-2023, ethnic minority candidates accounted for 16% of the eligible pool and 16% of recommendations. |

1.3 Professional background

| There is evidence of disparity for solicitors in legal judicial selection exercises compared to barristers. | For all legal exercises in 2022-2023, solicitors (48%) made up more applications than barristers (35%) - but constituted a smaller percentage of the recommendations (35% compared to 50%). |

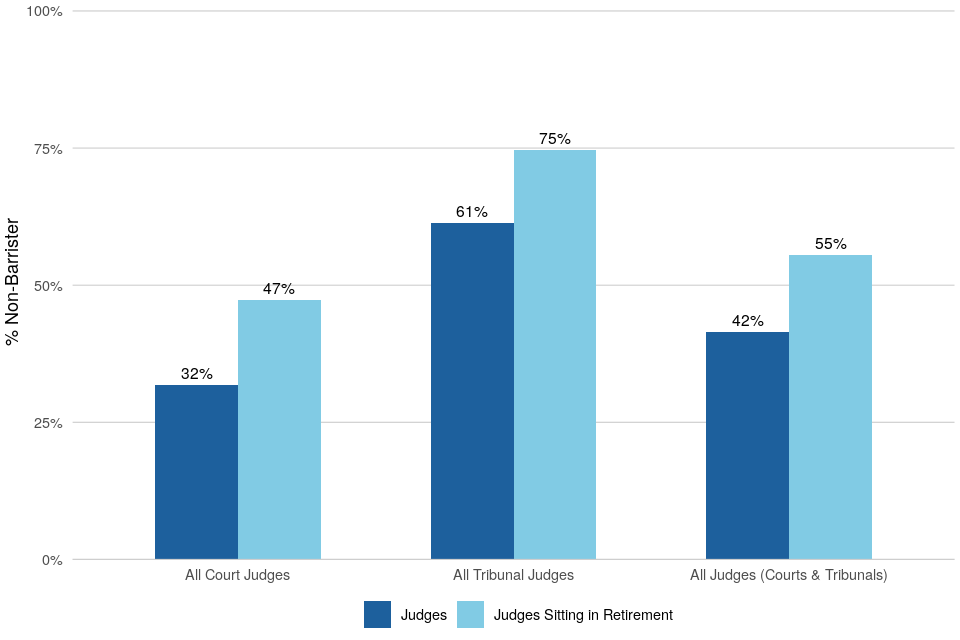

| Tribunal judges are twice as likely to have a non-barrister background than court judges | Overall, 32% of court judges and 61% of tribunal judges were from non-barrister backgrounds (mostly solicitors). |

1.4 Judges sitting in retirement

| In comparison to judges, a lower proportion of judges sitting in retirement are women or from an ethnic minority background, but a higher proportion have a non-barrister background. | Women constituted about a quarter (26%) of all judges sitting in retirement. Ethnic minorities made up about 6%. Non-barristers made up over half (55%) of judges sitting in retirement, compared to 42% for all current judges. |

1.5 Non-legal Members of Tribunals

| Compared with judges, a higher proportion of non-legal members are women, or from an ethnic minority background. | Of all non-legal tribunal members, women made up over a half (56%) and those with an ethnic minority background constituted 18%, compared to 42% and 11% for all judges respectively. |

1.6 Magistrates

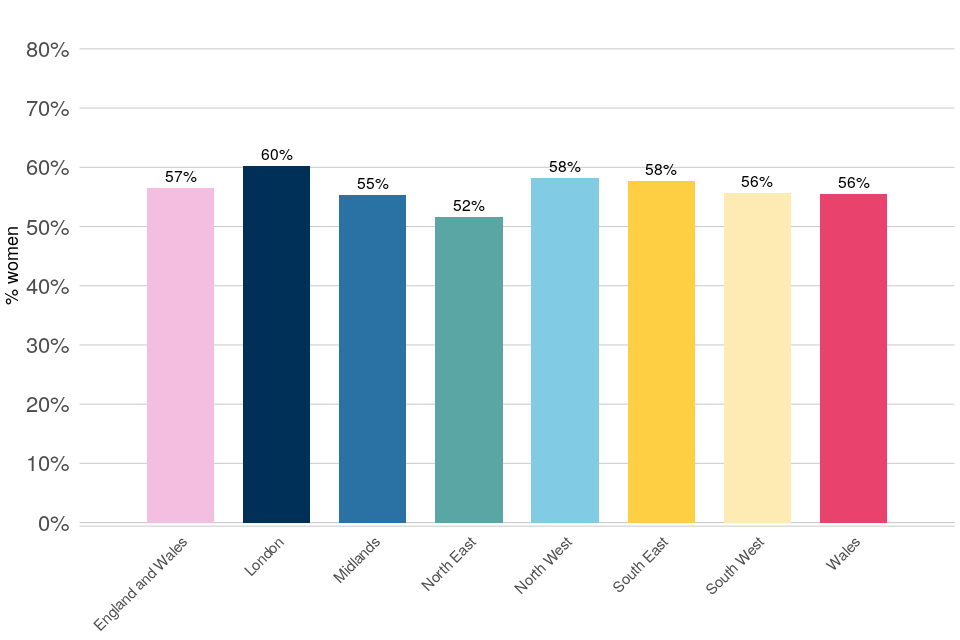

| The proportions of women and ethnic minority individuals was higher amongst the magistracy than in the judiciary. | Women represented 57% of all magistrates. Ethnic minorities made up 13%. |

| For women, the proportion applying to join the magistracy is comparable to those in post, but for ethnic minority individuals it is considerably higher. | Women constituted 56% of the applicants to become a magistrate. Ethnic minority individuals made up nearly a quarter (24%). |

2. Statistician’s Comment

Women are generally well represented throughout the judicial career path, from the legal professions who make up the eligible pool of future candidates, through the judicial appointments process, to the current judges in post. The main exception to this is seen in the more senior roles of the court judiciary where women tend to be under-represented.

When looking at the ethnic minority groups, there is a slightly different picture where representation amongst the legal professions is in line with the general population but is lower within the judiciary. There is no evidence of disparity in the judicial appointments process from eligible pool to recommendation between ethnic minorities overall and white candidates in legal exercises over the last three years. However, looking at the specific ethnic minority groups, individuals from an Asian/Asian British or black/black British background were less likely to be recommended for appointment relative to white candidates.

There are about ten times as many solicitors as barristers, but there are six former barristers to every four former solicitors in the judiciary. This reflects the significantly lower recommendation rates for solicitor compared to barrister candidates during the judicial appointments process, although solicitor-background candidates applying for more senior roles, requiring previous judicial experience, were recommended at very similar rates to barristers.

More robust statistical methodology used this year has also shown that there is no evidence of intersectional disparity with respect to sex, ethnicity and professional background from application to recommendation in the judicial selection exercises completed in the last three years. Instead, there are significant main effects of each – where women are appointed at higher rates, but ethnic minorities and solicitors are recommended at lower rates. For ethnic minorities this is a different result than the one described above for recommendation from the eligible pool, which reflects the higher proportion of ethnic minorities who apply from the eligible pool compared to white individuals.

Representation of women and those from an ethnic minority background was higher in those posts which do not require a legal background (magistrates and non-legal tribunal members), compared to judges currently in post.

3. Things you need to know

This is the fourth combined report bringing together diversity data on the legal professions, judicial appointments, and sitting judges and other post holders.

In this latest, edition covering 2022/23, some new information has been included for the first time. These are as follows:

- Time series data for the legal professions

- Magistrates recruitment data

- Intersection data for Magistrates in post

- Judges sitting in retirement

In addition, following an internal review of the report, a more robust approach to the methodology used for the analysis of intersectional effects of sex, ethnicity and professional background on judicial selection has been implemented. The results of this statistical analysis have now been combined with the intersectional figures for the legal professions and judicial office holders into a single separate chapter.

For the analysis of the data from the selection exercises, there are a number of terms used in the commentary that you may wish to know more about - such as ‘recommendation rate’, ‘relative rate index (RRI)’, ‘practical significance’, ‘statistical significance’ and ‘eligible pool’. A more detailed description and explanation of these terms can be found in the accompanying User’s Guide. We strongly suggest anyone who is new to these statistics read the user guide before this report.

Previous editions of this report have reported on gender and sex interchangeably. As of this year, to ensure a more accurate reflection of how most organisations collect data, the report will refer to the respondent’s sex rather than gender but noting the practices of any organisation where reporting differs.

In order to most appropriately assess the figures and trends in judicial diversity, comparisons in this publication are made against the relevant population in England and Wales, from which the legal professions and ultimately judges are derived. Here, the relevant population is defined to be those aged 25-74 in the 2021 Census general population. We also make comparisons to the Annual Population Survey’s (APS) economically active population, in order to recognise that not all members of particular demographic groups within the 25-74 age range are employed or actively looking for work.

4. Overview of the legal professions, selection exercises and judiciary

4.1 Legal professions

The legal professions form the pool from which the candidates who wish to become judges come. Table 1.1 provides information about the sex, ethnicity and age of these professionals by experience and seniority. As at 1 April 2023, there were 17,463 barristers, 159,574 solicitors and 8,191 Chartered Legal Executives.

The varying size of the professions should be kept in mind when interpreting the figures presented throughout this publication relating to the percentage of those in different professions with various characteristics (typically there will be more solicitors than barristers or Chartered Legal Executives).

4.2 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

During 2022-23 the JAC completed 36 judicial selection exercises[footnote 1] (excluding senior judicial appointments), 26 for legal posts and 10 for non-legal tribunal exercises. There were a total of 7,357 applications, resulting in 1,052 recommendations for immediate appointment (s87)[footnote 2]. Table 2.1 contains a full list of the exercises completed by the JAC between 1 April 2022 and 31 March 2023, and a detailed breakdown of the number of applications and appointments for each type of exercise run by the JAC.

Where two or more applicants are assessed as being of equal merit, the JAC can select an applicant for the purpose of increasing judicial diversity using the Equal Merit Provision (EMP) introduced by the Crime and Courts Act 2013[footnote 3]. EMP can be applied at both the shortlisting and recommendation for appointment stage. For exercises reporting in the 2022/23 period, as a result of using EMP, 184 candidates were advanced to the next stage of the process at the shortlisting stage, and 25 candidates were recommended at the selection day stage[footnote 4].

Levels of experience among applicants

Judicial selection exercises have a minimum statutory level of post qualification experience (PQE). However, the actual levels of applicants’ PQE are often greater than these minimum requirements. For 2022/23, of all applicants for court and tribunal positions requiring at least 5 years’ post-qualification experience, applicants had around 17.5-19 years’ experience on average[footnote 5]. Of those who applied for positions requiring at least 7 years’ of experience, applicants had around 21 years’ experience on average. More specifically:

- Court positions requiring 5 years’ PQE: the average PQE of applicants was around 17-19.5 years

- Court positions requiring 7 years’ PQE: the average PQE of applicants was 21 years

- Tribunal positions requiring 5 years’ PQE: the average PQE of applicants was around 18-19 years

- Tribunal positions requiring 7 years’ PQE: the average PQE of applicants was 20 years

Therefore, where information on the eligible pool for the legal professions are presented in the following chapters, these actual averages are used to allow a more meaningful comparison.

Comparison with previous years

This publication presents data for selection exercises which concluded during 2022-23 and does not draw comparisons with previous years. Historical comparisons can be affected by the number and type of exercises run in any given year, which can vary according to recruitment needs, and by when exercises are formally closed (before or after the report’s cut-off date of 1 April each year).

However, Table 2.5 does present figures on recommendations for appointment in those exercises where data is consistently available across the years.

4.3 Judicial office holders

Table 3.1 shows that as at 1 April 2023, by primary appointment, there were 3,483 court judges and 1,809 tribunal judges, with an additional 3,169 non-legal members of tribunals.

The overall number of court and tribunal judges has fluctuated over time, and there is no consistent pattern of increase or decrease. Since 2012 (the earliest year with data available on both courts and tribunals), the numbers of court judges (3,575 in 2012), and tribunal judges (2,060 in 2012) have both decreased.

Turnover in the judiciary tends to be relatively low, with 327 judges beginning their first appointment in 2022-23 (197 court, 130 tribunal judges) and 230 leaving in the same period (136 court, 94 tribunal).

As at 1 April 2023 there were 244 judges sitting in retirement in England and Wales.

4.4 Magistrates

There were 13,340 magistrates across England and Wales. Although an increase from last year, there has been an overall drop in the number of magistrates in recent years, decreasing by nearly a half from 25,170 since 2012. As a result of both changing workloads and working practices there was an oversupply of magistrates, and the numbers of magistrates were therefore allowed to reduce.

A new magistrates recruitment process was introduced in January 2022, and from then up to 31 March 2023 nearly 6,000 applications had been made to become a magistrate.

5. Sex

5.1 Legal Professions

Women remain generally well represented in the legal professions, with each profession showing a gradual increase in the past decade.

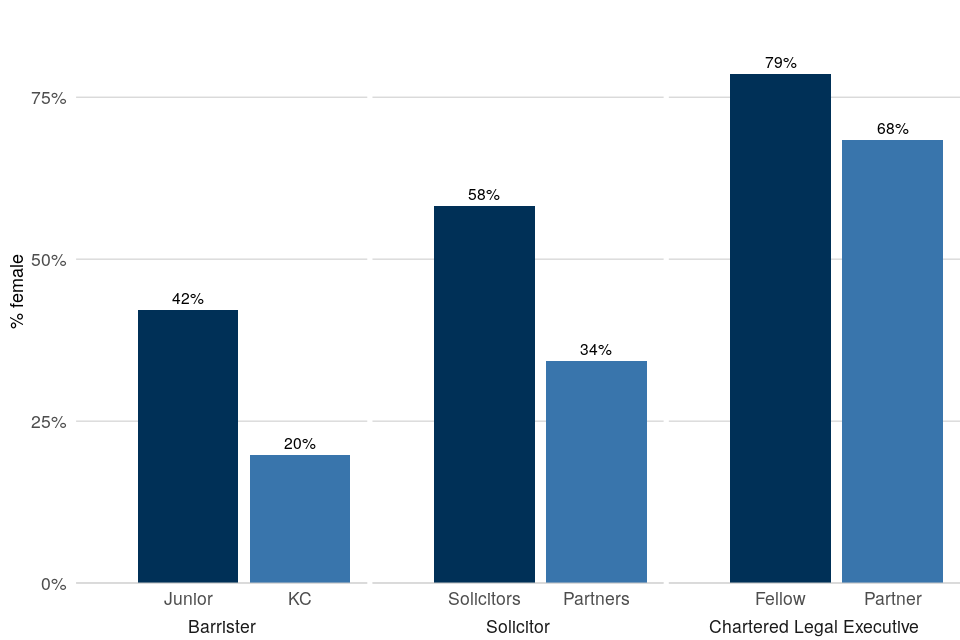

For all three professions, women are less likely to be at a higher seniority level than men.

Although women are generally well represented in the legal professions as a whole, as at April 2023 there was some variation in the proportion female between the three. This ranged from barristers at 40%, to solicitors at 53%, to Chartered Legal Executives at 77%.

Table 1.2 shows that the proportion of women in all three legal profession groups has gradually increased over the last decade, with solicitors increasing five percentage points, and barristers and Chartered Legal Executives increasing four percentage points each.

Post Qualification Experience

Table 1.1 shows that men dominate senior positions across the legal professions despite gains in female representation over the past decade[footnote 6]. Even though more women are entering the professions, men still tend to have greater years of experience.

-

Amongst barristers, half (51%) of men have 20+ years’ experience compared to a third (34%) of women; and, men are nearly three times more likely to be at a higher (King’s Counsel) seniority level than women (15% compared to 6%).

-

Amongst Chartered legal executives, 27% of men have 20+ years experience compared to 18% of women, and men are slightly more likely to be partners than women (19% compared to 12%).

For solicitors there is clearly an association between the rate of declaration for sex and PQE, with the lowest PQE band (0-4) only having a declaration rate of 29%. This means that analysis across the PQE bands by sex would be biased due to non-response and is therefore not included in this bulletin.

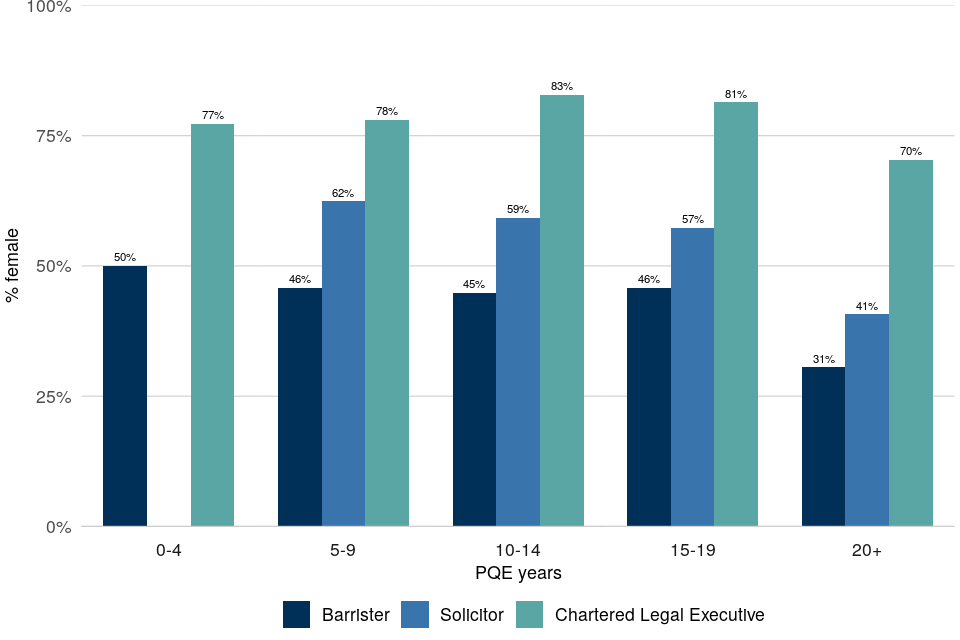

Figure 1: Representation of women in the legal professions by PQE band, April 2023[footnote 7] Across all legal professions, the proportion of women is notably lower for those having 20+ years’ experience.

Figure 2: Representation of women in the legal professions by seniority, April 2023 For all three professions, the proportion of women is lower at more senior compared to less senior levels.

5.2 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

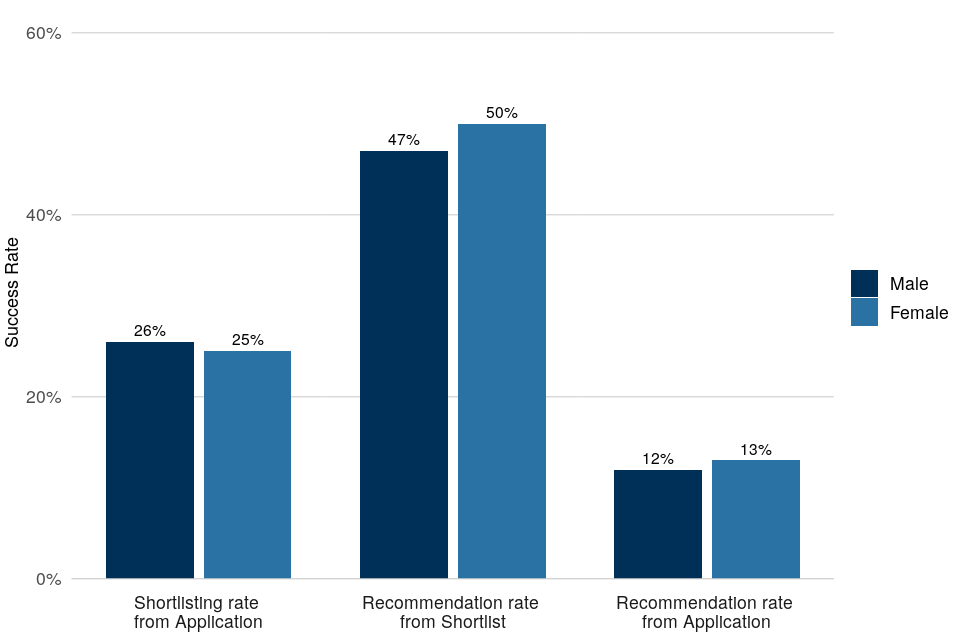

Overall, there is no evidence of any disparity in legal judicial selection in 2022-23 for women relative to men when comparing recommendation rates from the eligible pool.

Overall View

Table 2.2 shows that across all legal JAC exercises in 2022-23, women[footnote 8] accounted for 50% of the applications (3,238), 50% of those shortlisted (815) and 51% of the recommendations for appointment (407)[footnote 9].

These percentages suggest there was no disparity between men and women in these exercises. This is borne out by the estimated[footnote 10] RRI for the eligible pool to recommendation of 1.06, which shows that overall the likelihood of success is about 6% higher for women from the eligible pool compared to men. This difference is not statistically or practically significant[footnote 11]. Similarly there was no disparity between men and women in these exercises from application to recommendation (RRI of 1.04).[footnote 12]

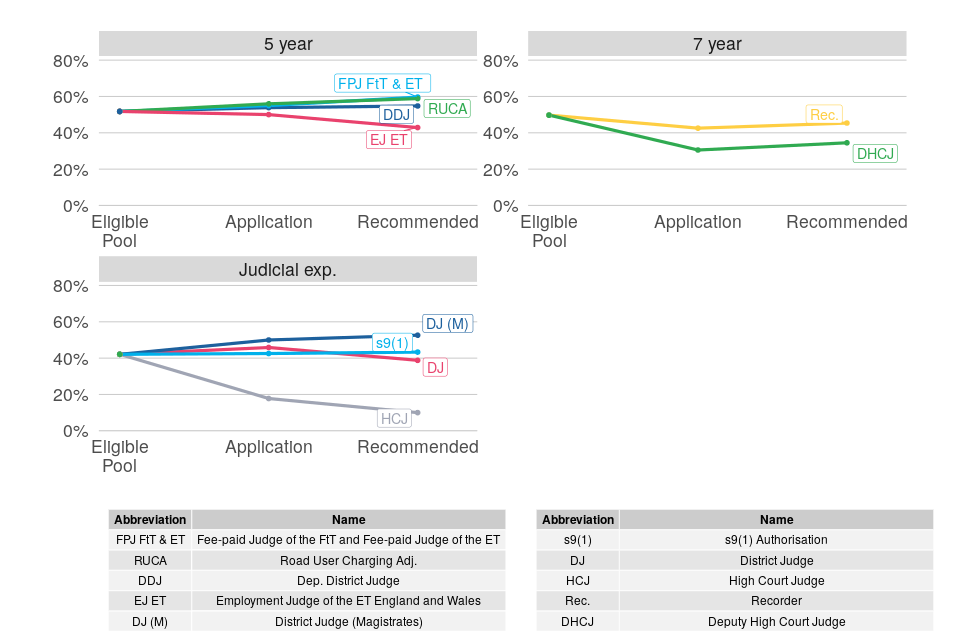

This lack of difference between men and women is also shown by their similar progressions rates in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Progression of applicants through the exercise stages by sex (all legal exercises completed in 2022-23).

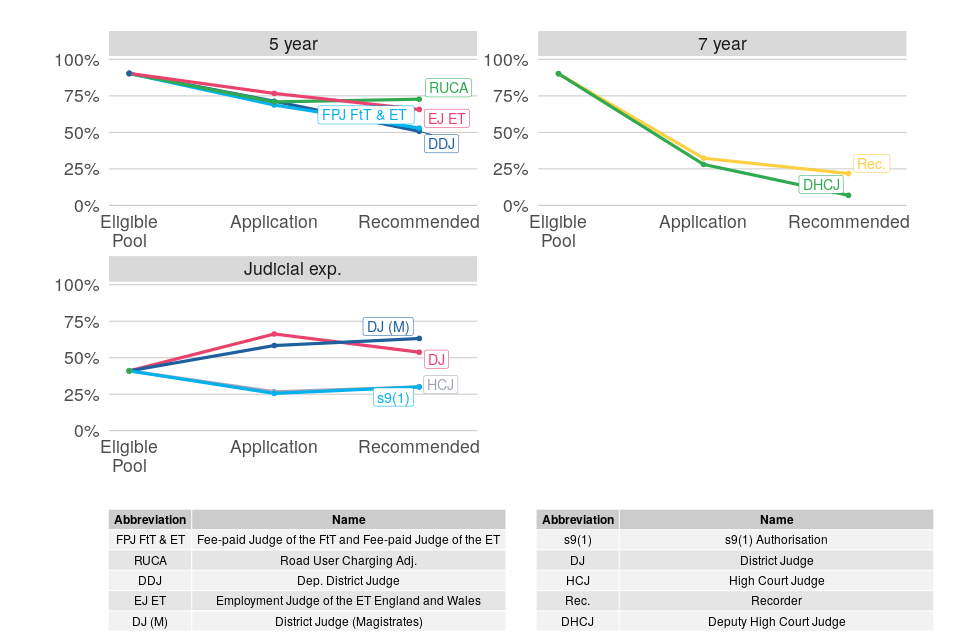

Exercise-specific Analysis

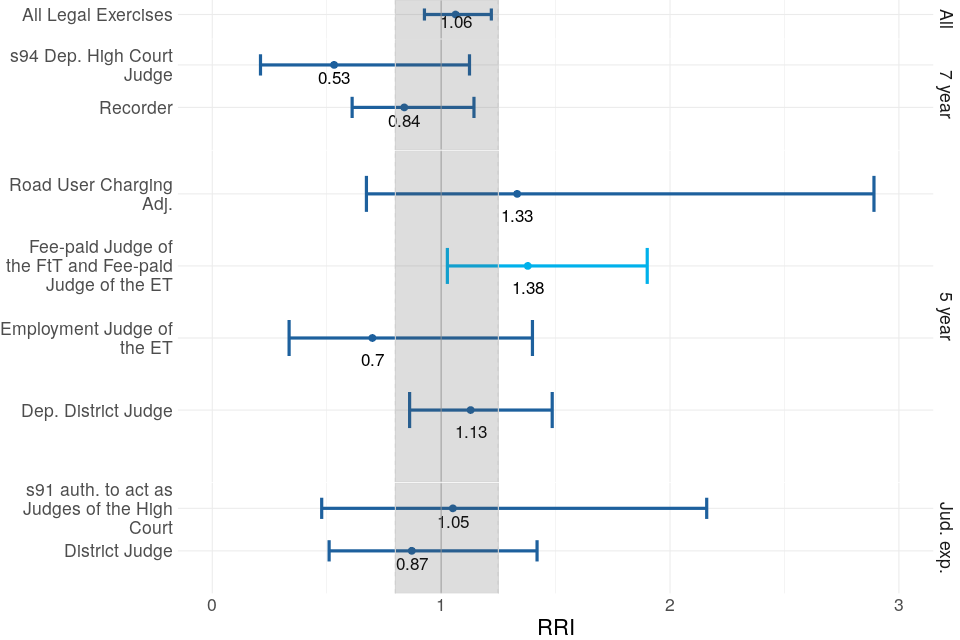

In 2022-23, statistically significant sex disparity only occurs in the Fee-paid Judge of the First-tier Tribunal and Fee-paid Judge of the Employment Tribunal (England and Wales) exercise (Figure 4).

For this exercise the RRI from eligible pool to recommendation of 1.38 indicates that the odds of success for women were 38% higher than for men[footnote 13]. However, the RRI value for application to recommendation was 1.21 and not statistically significant[footnote 14], meaning that that there is no evidence of disparity in success rate between men and women when looking at applicants rather than the eligible pool.

Figure 4: RRI for women compared to men, from eligible pool to recommendation (all legal exercises completed in 2022-23).

For the above figure note that statistically significant results – where the confidence interval (represented by the arms extending from each dot) does not overlap the parity line (1 on the x-axis) - are light blue. The tolerance zone is shaded grey (0.8 to 1.25); results falling within this zone are considered to represent a disparity which is not large enough to be considered practically important (and tend not to be statistically significant).

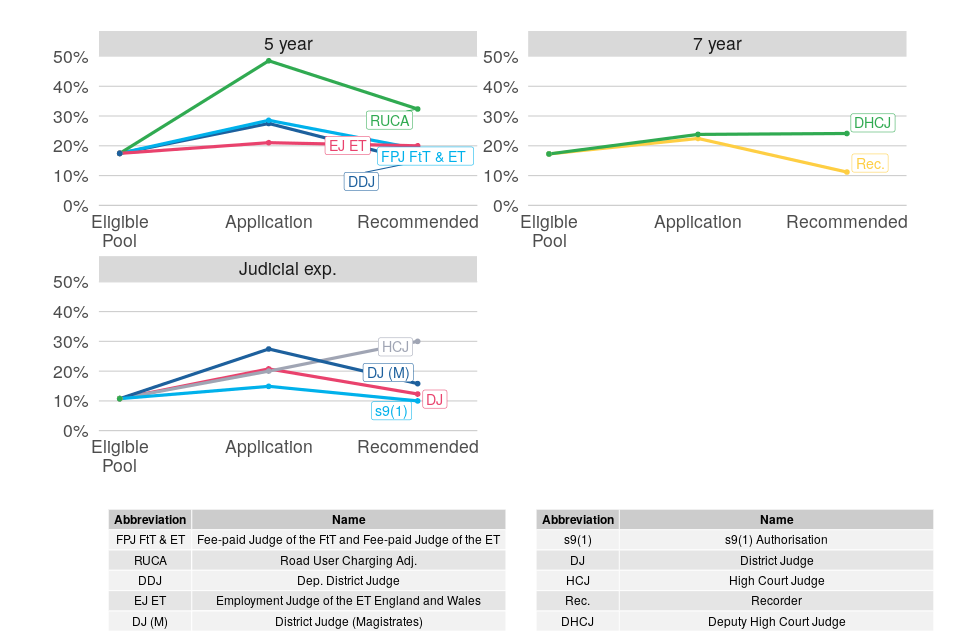

Representation percentages (Figure 5) help to show the progress of women at different stages of the selection process. In comparison to the eligible pool, the representation of women was higher at the recommendation for appointment stage for three of the ten large legal exercises, with one the same.

Please note that the lines for Fee-paid Judge of the First-tier Tribunal and Fee-paid Judge of the Employment Tribunal (FPJ FiT & ET) and Road User Charging Adjudicator (RUCA) are almost identical on the graph.

Figure 5: Representation of women at different exercise stages, by eligible pool type (5 years’ PQE, 7 years’ PQE, and Previous judicial experience) for large legal exercises completed in 2022-23.

5.3 Judicial Office Holders

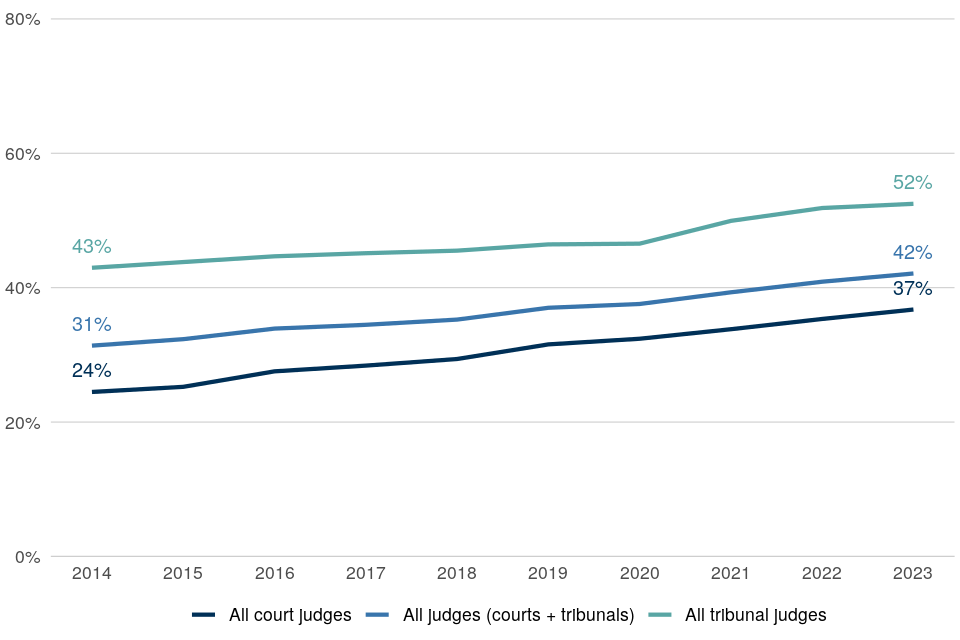

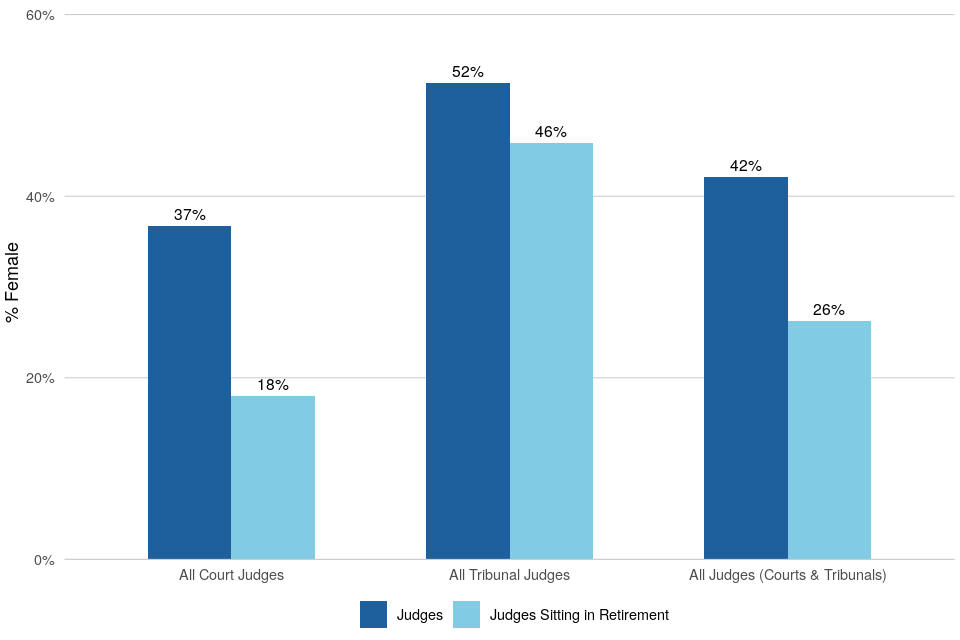

Female representation among judges in post has increased over recent years, for both courts and tribunals judges.

Judges in post

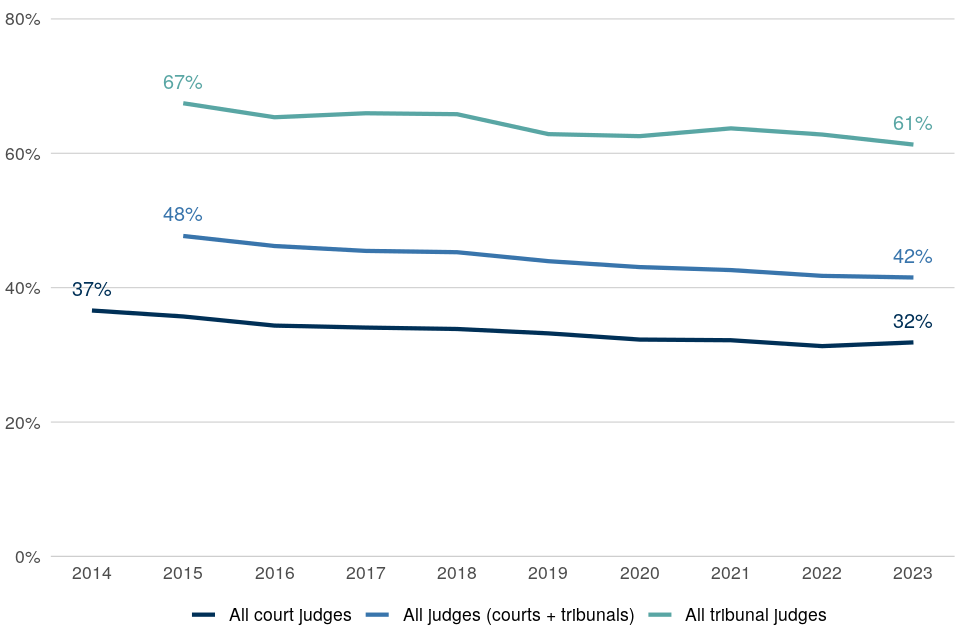

Table 3.4 shows that as at 1 April 2023, women represented 37% of all court judges, 13 percentage points higher than in 2014[footnote 15], and 52% of all tribunal judges, 9 percentage points higher than in 2014 (Figure 6).

Comparing men and women in their distribution across judicial positions in courts, Table 3.1 shows that for the latest year, the distribution of female court judges across the roles above recorder was roughly equivalent to that for male judges – even though there are comparatively fewer at higher levels as a proportion of each role. Men are more likely to be recorders than women, while women are more likely to be a District Judge or Deputy District Judge compared to men.

Overall, the distribution of female tribunal judges across roles is generally similar to that for the men.

Figure 6: Proportion of court and tribunal judges that were women as at 1 April, from 2014.

For context, women account for just over half of the general population aged 25-74[footnote 16] and just under half of the economically active population of England and Wales. However, as judicial roles require substantial legal experience, a direct comparison with the general population does not provide as much insight on progression in the representation of women in the judiciary as considering the makeup of the legal professions (as presented in the earlier section).

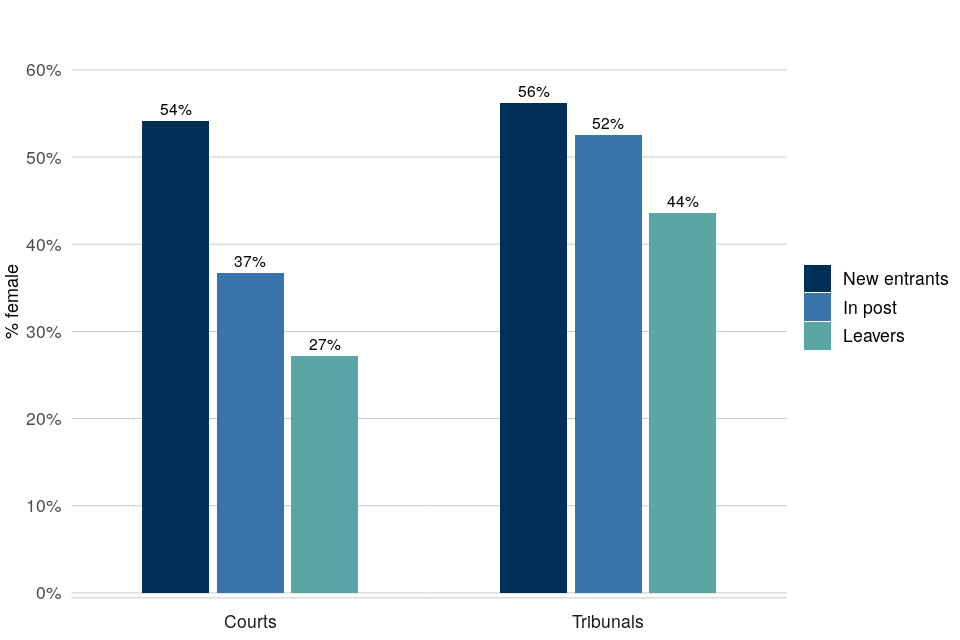

Entrants and leavers

More women entered the judiciary compared to men during 2022-23, and conversely more men left the judiciary compared to women during the same period (Figure 7).

New entrants: Table 3.1 shows that the proportion of female judges in post (8%) who were new entrants to the judiciary – those not previously holding a judicial appointment – was higher than that for males (5%) during 2022-23[footnote 17] (Figure 7).

Promotions: The proportion of female judges in post who were promoted in 2022/23 was the same as that for males (2%) - although the actual numbers are fairly small and can be affected year-on-year by the mix of roles involved.

Leavers: The proportion of female judges in post (4%) who had left the judiciary during 2022/23 was slightly less than that for males (5%).

Figure 7: Representation of women among court and tribunal judges leaving and joining the judiciary, 1 April 2022 – 31 March 2023.

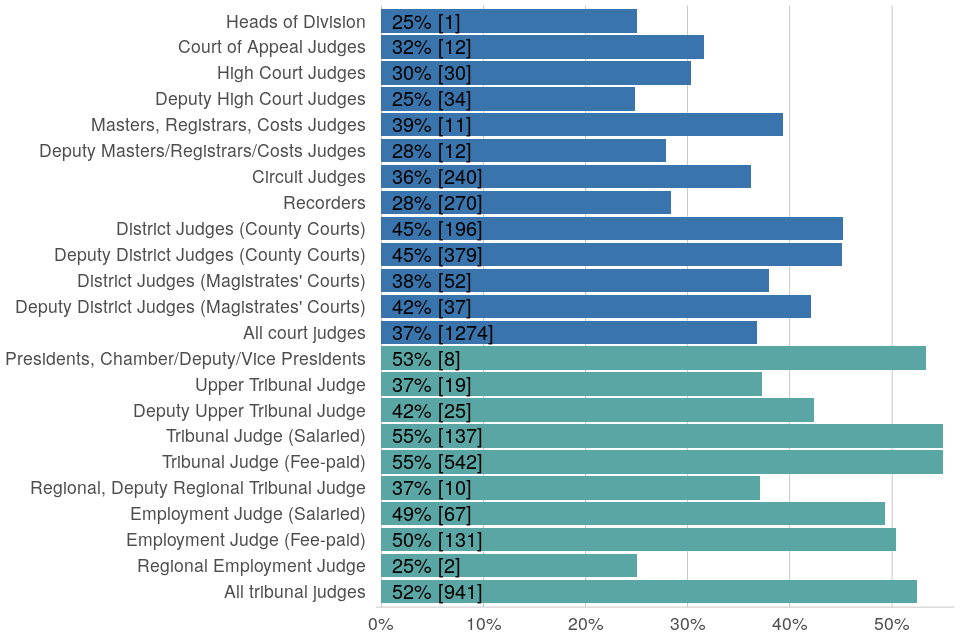

Patterns by type of appointment

The representation of women across the judiciary varied by appointment type and seniority (Figure 8).

In the courts, women made up 30% of judges in more senior posts (High Court and above). The highest level of representation for women was among the County Court judges (District Judges and Deputy District Judges) at 45%.

In tribunals, women accounted for more than half (53%) of the most senior roles (Presidents)[footnote 18].

Figure 8: Representation of women among court and tribunal judges by appointment, 1 April 2023.

Patterns by region

The representation of women across the court judiciary also varies considerably by region, from 31% in Wales, to 43% in the South East. Variations may reflect the nature of the appointments in the different regions, as well as the underlying regional make-up of both the general population and the eligible pool. Further information is available in table 3.2.

6. Ethnicity

6.1 Legal Professions

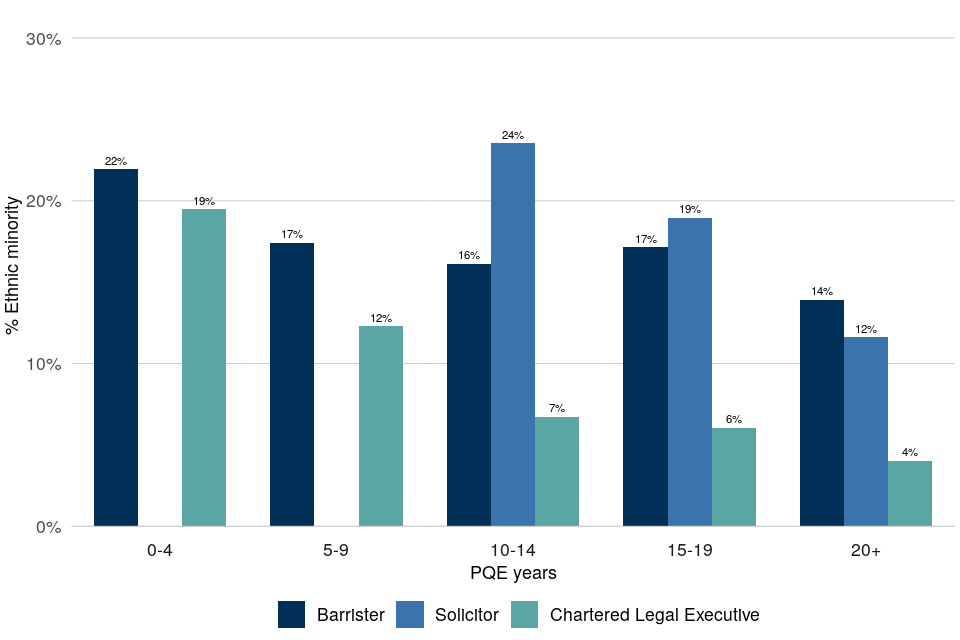

There has been a gradual increase in the representation of ethnic minorities in all three legal professions over the last decade.

Representation of individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds is lower at the more senior levels for each of the legal professions.

Overall Picture in Each Profession

Over the last decade, there has been a gradual increase in the representation of ethnic minorities amongst the three legal professions. For barristers the ethnic minority proportion increased three percentage points to 16%, for solicitors it was four percentage points to 19%, and for Chartered Legal Executives it doubled from 5% to 11%.

For the latest year, as at 1st April 2023, for all three professions the proportion of individuals self-identifying as ethnic minority was broadly in line with those of the relevant working population (25-74) in England and Wales from the 2021 Census.[footnote 19]

The main variation was in the representation of Asian or Asian British ethnicity which was higher for solicitors compared to the working population (12% compared to 9%), and in the representation of individuals of mixed ethnicity which was twice as much in barristers as for the working population (4% compared to 2%).

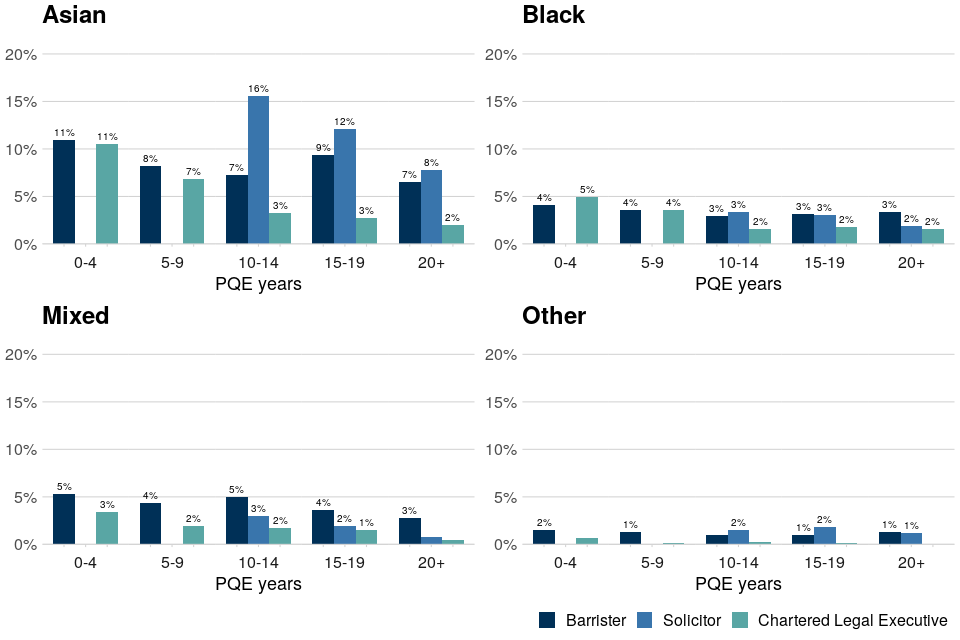

Post Qualification Experience

In practice, most applicants for judicial roles have more than the minimum experience. For court and tribunal posts requiring at least 5 years’ experience, applicants have on average around 17.5 to 19 years’ experience, and for court and tribunal posts requiring 7 or more years of experience, applicants have on average around 21 years’ experience[footnote 20]. Table 1.1 shows that:

- Amongst barristers, 50% of those with an ethnic minority background have 15 or more years’ PQE, with 37% having 20 or more years’ PQE, compared to 57% and 45% respectively for white barristers.

- Amongst Chartered legal executives, 15% of those with an ethnic minority background have 15 or more years’ PQE, with 7% having 20 or more years’ PQE, compared to 38% and 22% respectively for white Chartered legal executives.

For solicitors there is clearly an association between the rate of declaration for ethnicity and PQE, with PQE bands below 10 having declaration rates of below 60%[footnote 21]. This means that analysis across the PQE bands by ethnicity would be biased due to non-response and is therefore not included in this bulletin.

Figure 9: Representation of ethnicity groups in legal professions by PQE band, April 2023[footnote 22]

Figure 10: Representation of ethnic minority in the legal professions by PQE band, April 2023[footnote 22]

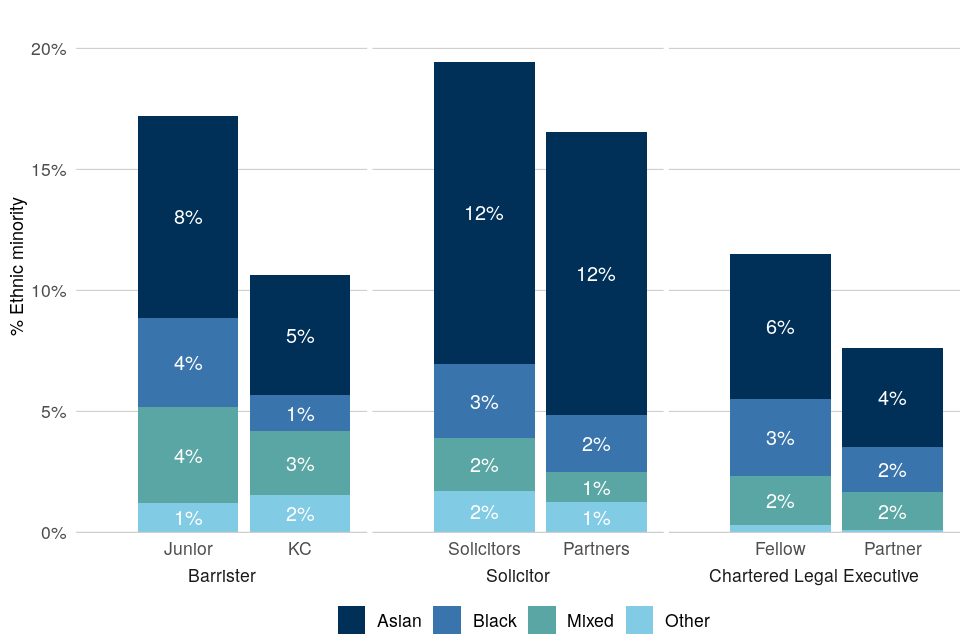

Seniority[footnote 23]

Table 1.1 shows that ethnic minority barristers are slightly less likely to be at a higher level (King’s Counsel) than white barristers (8% compared to 12%). This is also the case for ethnic minority solicitors compared to white solicitors (22% compared to 26%), and for ethnic minority Chartered legal executives compared to their white colleagues (9% compared to 14%).

At a somewhat more granular level, black or black British individuals are less represented in more senior roles compared to junior roles in all three legal professions. This is also the case in two of the three professions for Asian or Asian British individuals and those with mixed ethnicity (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Representation of each ethnic minority group in the legal professions by seniority, April 2023

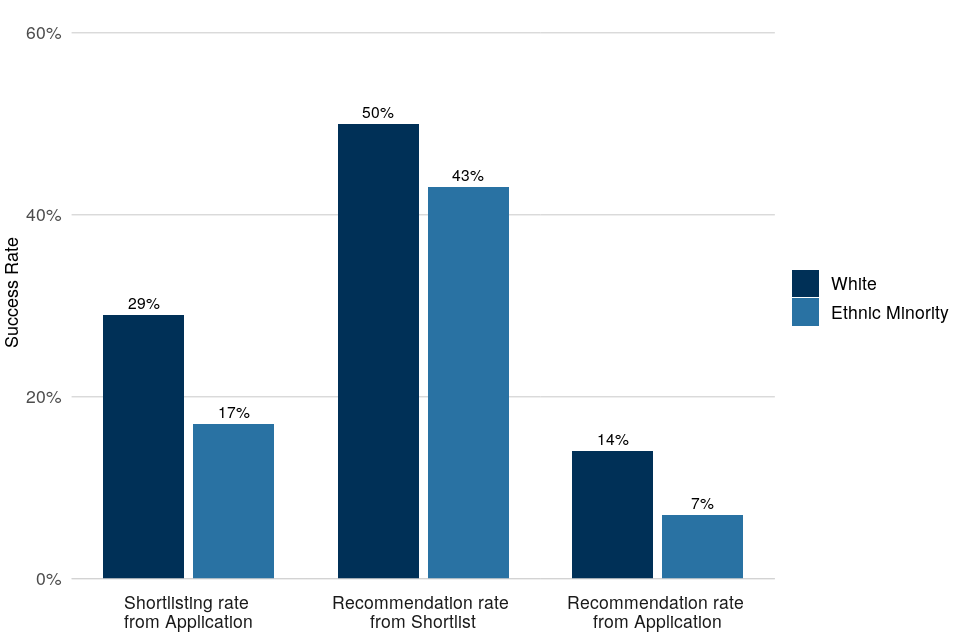

6.2 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

Single-year Analysis: 2022/2023

Ethnic minority candidates were recommended for legal exercises in line with their representation in the eligible pool, suggesting no disparity in judicial appointments relative to white candidates when comparing recommendation rates from the eligible pool.

However, the proportion of ethnic minority candidates decreased between each exercise stage, from application to shortlisting to recommendation for appointment.

For selection exercises that closed in the 2022-2023 financial year, candidate numbers at the application, shortlisting and recommendation for appointment stages were not high enough to produce and publish statistics for the specific ethnic minority groups without risking disclosure of sensitive information. Therefore, for this most recent year of data, we consider candidates from ethnic minority backgrounds together as one group and compare their progression outcomes to white candidates.

Later in this section we have grouped together exercises from 2020 to 2023 in order to generate a sufficient sample of candidates from which we can look in more detail at ethnic minority backgrounds in the judicial appointments process.

Overall View

Across all legal exercises in 2022-23:

- Ethnic minority individuals comprised 16% of the eligible pool, and when comparing eligible pool to recommendation rates it was found to be the same as that for white candidates (shown by the estimated[footnote 24] RRI of 1.00, Figure 13)[footnote 12]. This indicates that for this year there was no disparity between ethnic minority and white candidates when comparing recommendation rates from the eligible pool.

- Ethnic minority individuals accounted for 27% (1,767) of applications, and for 16% (128) of those recommended for appointment[footnote 25]. This is reflected in the progress rates from application which were lower for ethnic minority candidates compared to those for white candidates (Figure 12), although it is notable that the bigger differential in rates is seen from application to shortlisting, rather than shortlisting to recommendation.

Figure 12: Progression of applicants through the exercise stages by ethnicity (all legal exercises completed in 2022-23).

Exercise-specific Analysis

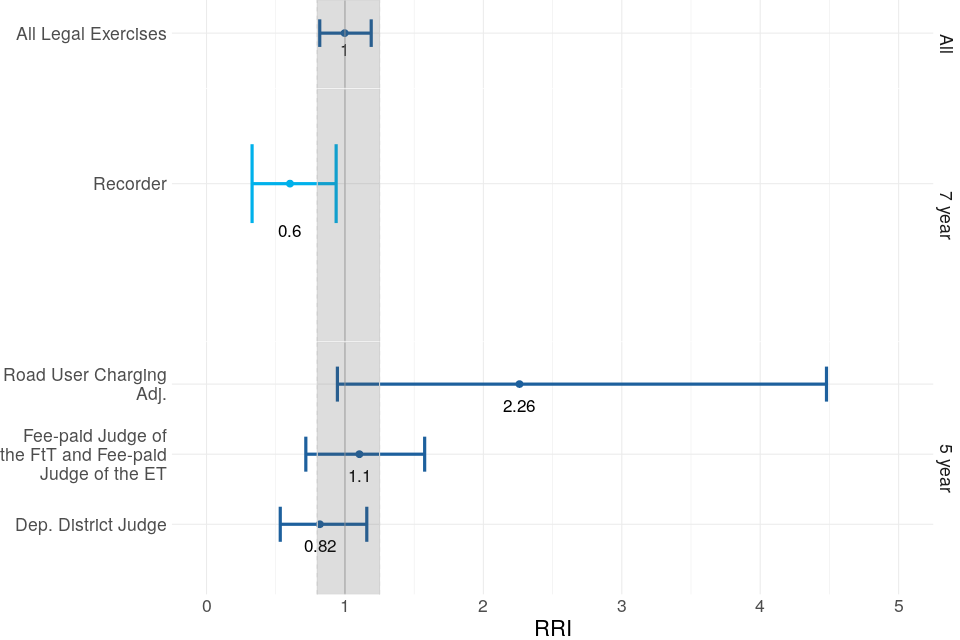

When considering ethnic minority candidates relative to white candidates (Figure 13):

- Of the four exercises for which an RRI could be calculated, only one (Recorder with an RRI value of 0.6) had a practically and statistically significant result from the eligible pool to recommendation. So for that exercise there was evidence of a disparity in favour of white candidates, and for the others there was no evidence of any such disparity.

- Another exercise (Road User Charging Adjudicator) had an RRI value from eligible pool to recommendation of 2.26 but was not statistically significant. However, the RRI value for application to recommendation was a statistically significant 0.51 (Table 2.2). This suggests that there was evidence of disparity in the success between ethnic minority and white candidates when looking at applicants rather than the eligible pool. These two contrasting measures reflect the much higher proportion of applicants from an ethnic minority background (49%) compared to the eligible pool (17%), such that although they dropped off significantly through the process, ethnic minority candidates were still recommended proportionately (32%) higher than the eligible pool (Figure 14).

- For the remaining two exercises large enough to present, the RRI values from eligible pool to recommendation were neither practically nor statistically significant, suggesting no disparity. However, their RRI values from application to recommendation were both practically and statistically significant, suggesting evidence of a disparity in the success between ethnic minority and white candidates when looking at applicants rather than the eligible pool.

Figure 13: RRI for ethnic minority compared to white candidates from eligible pool to recommendation (large legal exercises completed 2022-23).

For the above figure note that statistically significant results – where the confidence interval (represented by the arms extending from each dot) does not overlap the parity line (1 on the x-axis) - are light blue. The tolerance zone is shaded grey (0.8 to 1.25); results falling within this zone are considered to represent a disparity which is not large enough to be considered practically important (and tend not to be statistically significant).

Ethnic minority representation in exercises was higher at the application stage than in the eligible pool, but tended to be lower at recommendation than at the application stage (Figure 14). In all ten of the large legal exercises in 2022/23, ethnic minority representation in applications was higher than in the corresponding eligible pool, but in eight of those ten ethnic minority representation at recommendation was lower than at application. The two exercises where there was no drop-off from application to recommendation were for High Court Judge and s9(4) Deputy High Court Judge.

Of the ten exercises, seven had a higher ethnic minority representation in recommendations compared to the corresponding eligible pool. Of the three exercises that did not have a higher representation at the recommendation stage, the exercise for Recorder had the largest difference, followed by Deputy District Judge.

Figure 14: Representation of ethnic minority candidates at different exercise stages, by eligible pool type (large legal exercises completed in 2022-23).

6.3 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

Three-year Analysis: 2020 to 2023

For the past three years of legal exercises, there was no disparity in judicial appointments for ethnic minority candidates relative to white candidates when comparing recommendation rates from the eligible pool.

There is evidence to suggest disparity in the recommendation rate from eligible pool of Asian and black candidates compared to white candidates.

To present more detailed statistics on the progression of candidates from Asian, black, mixed and other ethnic backgrounds without risking disclosure of sensitive information, we have aggregated data from the three most recent years of judicial appointments. The statistics presented below are produced from data on selection exercises that closed between 1 April 2020 and 31 March 2023.

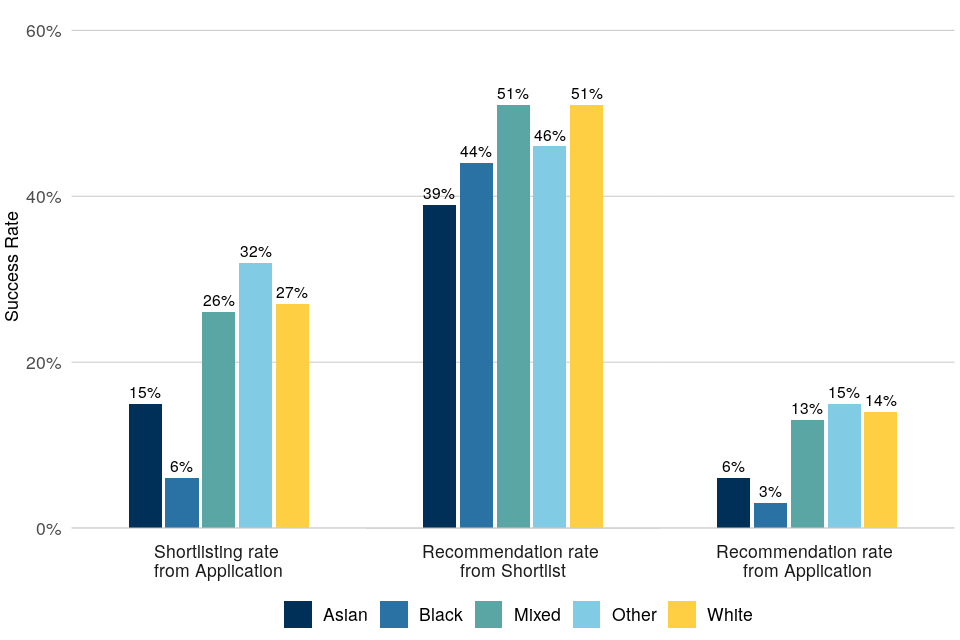

Table 2.7 shows that across all legal exercises in this three-year period, ethnic minority candidates together constituted 25% of applications (3,943) and 14% of recommendations for appointment (266), whilst making up 15% of the average eligible pool. The rate of recommendation from the eligible pool for ethnic minority candidates was an estimated 13% lower than the rate for white candidates (a statistically but not practically significant result) during this period.

Across all legal exercises that closed between 1 April 2020 and 31 March 2023:

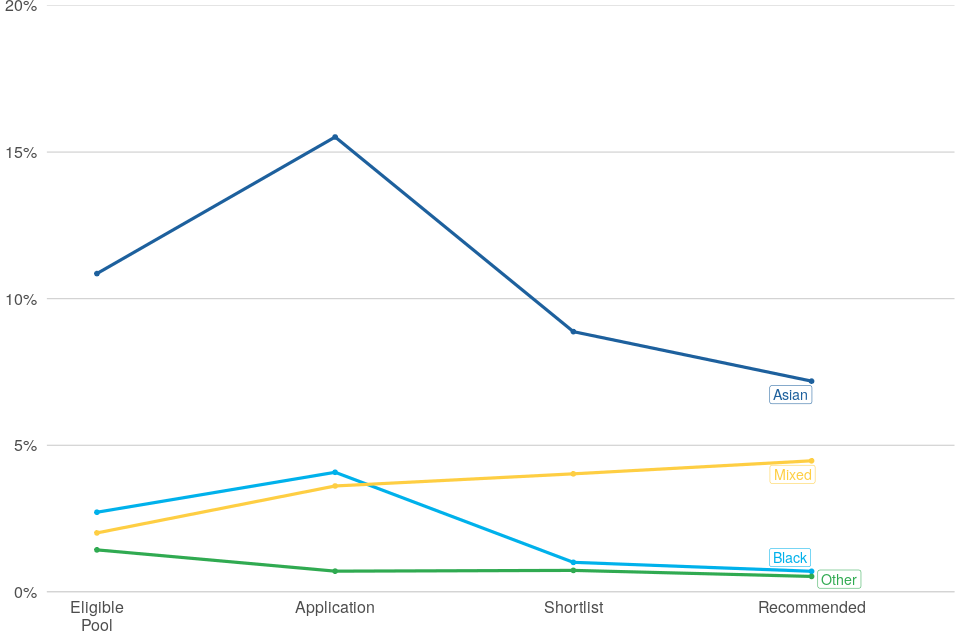

Asian or Asian British

- Asian or Asian British representation among applicants was significantly higher than it was in the eligible pool, but subsequently dropped at the shortlisting and recommendation for appointment stages (Figure 15).

- This is reflected in the progression rates in Figure 16 which show lower rates for Asian candidates compared to white candidates for all stages.

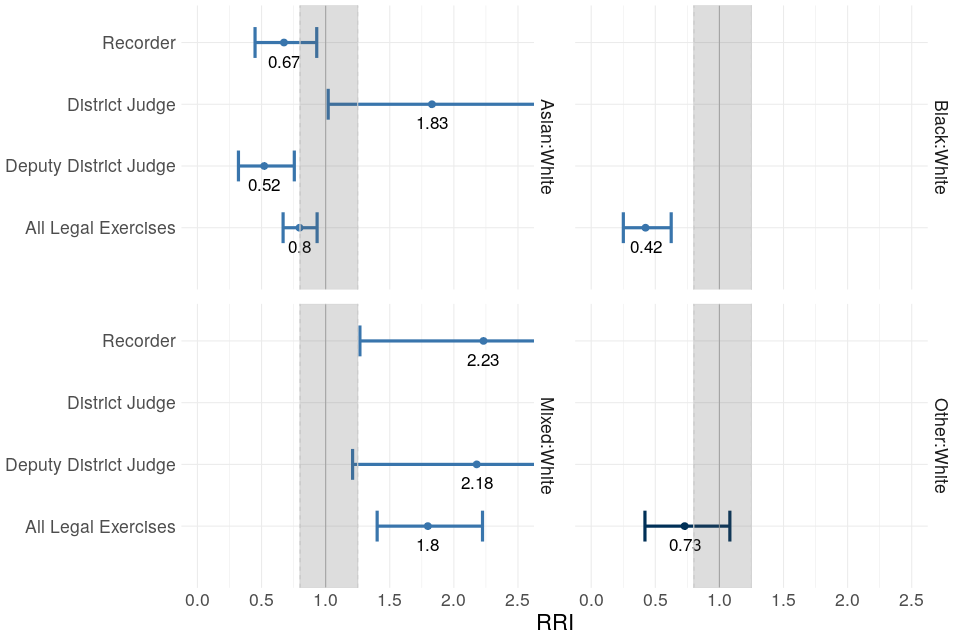

- The likelihood of success from eligible pool to recommendation was 20% lower for Asian candidates than it was for white candidates, shown by the estimated RRI of 0.8 (Figure 17). This estimate is both practically and statistically significant, meaning that we can be confident that the result suggests a real difference in the progression rate for Asian candidates compared with white candidates.

For all those individual exercises for which an RRI could be calculated, Asian candidates had lower eligible pool to recommendation rates relative to white candidates, for the three Recorder and three Deputy District Judge exercises, with RRI values of 0.67 and 0.52 respectively. These were found to be both practically and statistically significant, indicating that there was indeed evidence of a real difference between Asian and white candidates in those exercises. For the five District Judge exercises completed in the period 2020-23, the eligible pool to recommendation rate had a practically and statistically significant RRI of 1.83, again indicating evidence of a real difference, but this time in favour of the Asian candidates.

Black or black British

- Similar to Asian candidates, black or black British representation among applicants was higher than it was in the eligible pool, but dropped subsequently at the shortlisting and recommendation for appointment stages (Figure 15).

- Again, this is reflected in the progression rates in Figure 16 which show lower rates for black candidates compared to white candidates for all stages, particularly from application to shortlisting.

- The likelihood of success from eligible pool to recommendation was 58% lower for black candidates than it was for white candidates, shown by the estimated RRI of 0.42 (Figure 17). This estimate is both practically and statistically significant, meaning that we can be confident that the result suggests a real difference in the progression rate for black candidates compared with white candidates.

There were no individual exercise types which had high enough numbers of black recommended candidates for an RRI covering all stages to be reliably calculated.

Mixed Ethnicity

- The representation of mixed ethnicity candidates among applicants was again higher than it was in the eligible pool, but unlike for Asian and black candidates it remained higher at the shortlisting and recommendation for appointment stages (Figure 15).

- Accordingly, the progression rates for candidates of mixed ethnicity are comparable to those of white candidates (Figure 16).

- In contrast to Asian and black candidates, the likelihood of success from eligible pool to recommendation was 80% higher for mixed ethnicity candidates than it was for white candidates, shown by the estimated RRI of 1.80 (Figure 17). This estimate is both practically and statistically significant, meaning that we can be confident that there is a real difference between mixed and white candidate progression from eligible pool to recommendation.

For all those individual exercises for which an RRI could be calculated, candidates of mixed ethnicity had higher eligible pool to recommendation rates in both the Recorder and Deputy District Judge exercises compared to white candidates (RRIs of 2.23 and 2.18 respectively). These were found to be both practically and statistically significant, indicating that there was indeed evidence of a higher likelihood of success for mixed ethnicity candidates compared to white candidates in those exercises.

Other Ethnicities

- Candidates with an ethnicity other than white, Asian, black, or mixed ethnicity represented 1% of all candidates at every stage from eligible pool to recommendation (Figure 15).

- As with those of mixed ethnicity, the progression rates for these other ethnicity candidates are comparable to those of white candidates (Figure 16).

- The likelihood of success from eligible pool to recommendation was 27% lower for candidates of other ethnicity than it was for white candidates, as suggested by the estimated RRI of 0.73. However, this figure is not statistically significant, suggesting no real difference between white candidates and those from other ethnic backgrounds.

There were no individual exercise types which had high enough numbers of candidates from other ethnic groups for an RRI covering all stages to be reliably calculated.

Figure 15: Representation of ethnic minority candidates at different exercise stages, legal exercises between April 2020 and March 2023

Figure 16: Progression of applicants through the exercise stages by ethnicity (all legal exercises completed between April 2020 and March 2023)

Figure 17: RRIs for ethnic minorities compared to white candidates from eligible pool to recommendation, in legal selection exercises between April 2020 and March 2023.

For the above figure note that statistically significant results – where the confidence interval (represented by the arms extending from each dot) does not overlap the parity line (1 on the x-axis) - are light blue. The tolerance zone is shaded grey (0.8 to 1.25); results falling within this zone are considered to represent a disparity which is not large enough to be considered practically important (and tend not to be statistically significant).

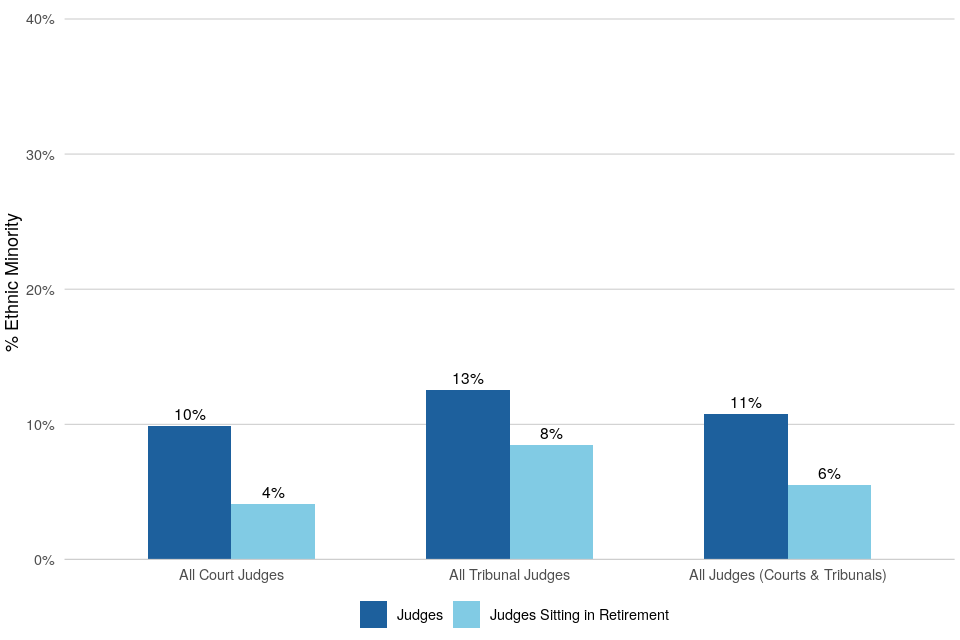

6.4 Judicial Office Holders

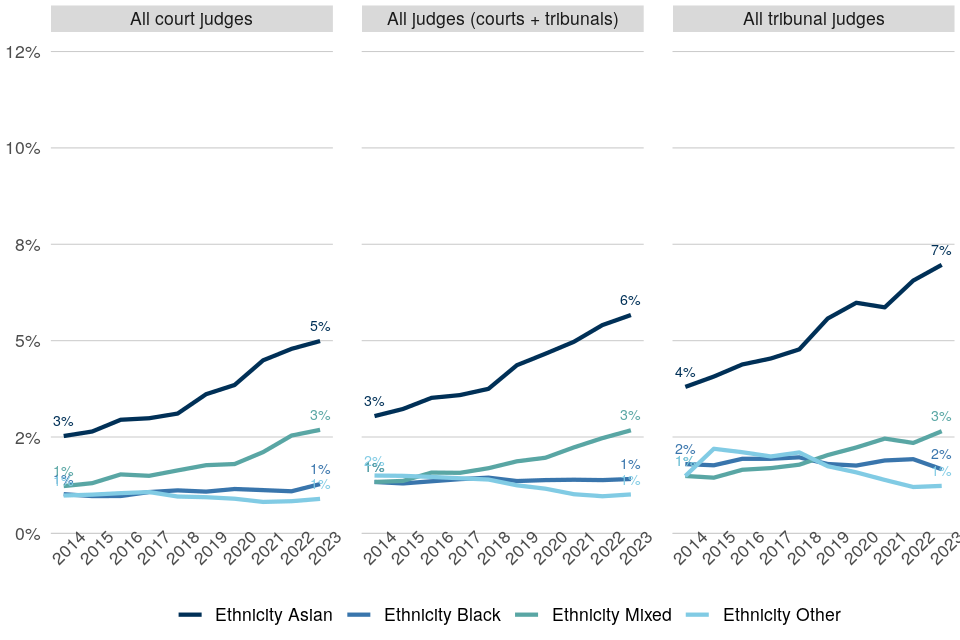

The proportion of Asian and mixed ethnicity individuals in the judiciary has slowly increased since 2014, while the proportion of black and other ethnic minority individuals has stayed the same in that time.

Judges in post

Figure 18 shows that, as at 1 April 2023, ethnic minority individuals representation increased by four percentage points compared to 2014[footnote 15] for both court and tribunal judges.

At a somewhat more granular level, over the same ten-year period, there was a three percentage-point rise in Asian individuals (which is equivalent to an almost doubling in representation), and a one percentage point increase for those of mixed ethnicity. In contrast, for black candidates and those of ethnicity other than Asian, black, mixed or white, there was no overall change in their representation between 2014 and 2023.

Figure 18: Representation of ethnic minority individuals among court and tribunal judges, 2014 to 2023.

As very broad context, comparisons can be made between the ethnic minority representation among judges with that of the general working age (25-74) population of England and Wales, by age group, as determined by the 2021 Census[footnote 26] (Figure 19). However, this may not be an entirely suitable comparator as judges tend to be drawn from the upper end of the age distribution. For this reason, characteristics of the legal professions, presented above, may provide more appropriate context when comparing the ethnic minority proportion among the judiciary - namely 11% of all judges being of ethnic minority compared to 16% of all barristers, 19% of all solicitors and 11% of all Chartered Legal Executives.

Despite limitations in making comparisons, the age of judges should be kept in mind when considering variations in the proportion of ethnic minority, for example by appointment type.

Figure 19: Representation of ethnic minority individuals by age group - court and tribunal judges (2023) compared to general population (2021 Census)[footnote 27]

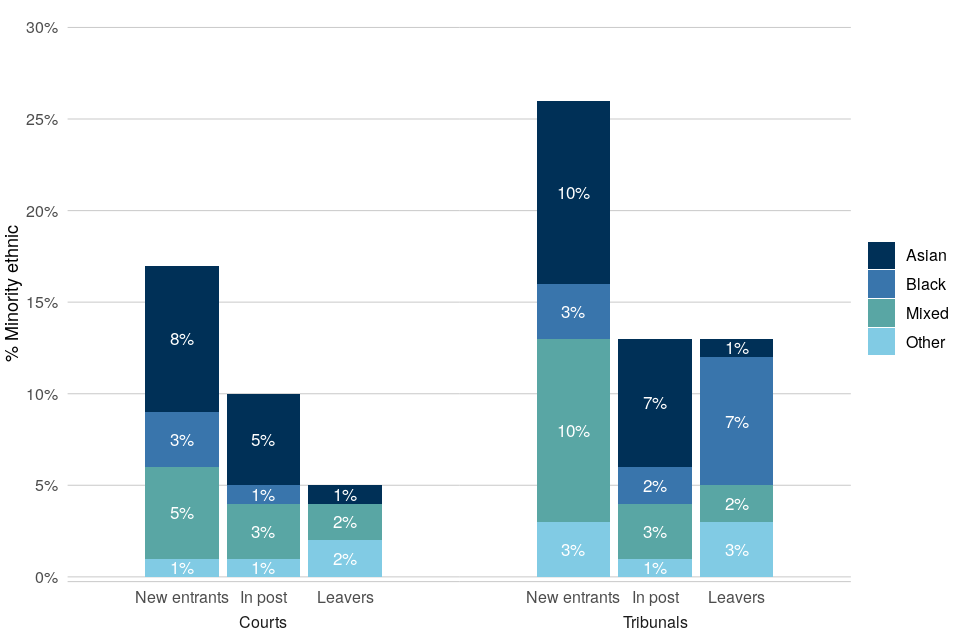

Entrants, Promotions and Leavers

Entrants: during 2022-23, the proportion of ethnic minority individuals entering the judiciary was higher than of those in post as at 1 April 2023 for both courts and tribunals (Figure 20). As with sex, these figures are likely to fluctuate depending on which roles were appointed during the year.

Promotions: Table 3.1 shows that the proportion of ethnic minority judges in post who were promoted in 2022/23 was the same as that for white judges (2%) - although the actual numbers are fairly small and can be affected year-on-year by the mix of roles involved.

Leavers: The proportion of ethnic minority judges in post who left the judiciary during 2022/23 was marginally less than for white judges (3% compared to 4%).

Figure 20: Representation of ethnic minority individuals among court and tribunal judges leaving and joining the judiciary, 1 April 2022 – 31 March 2023

Patterns by type of appointment

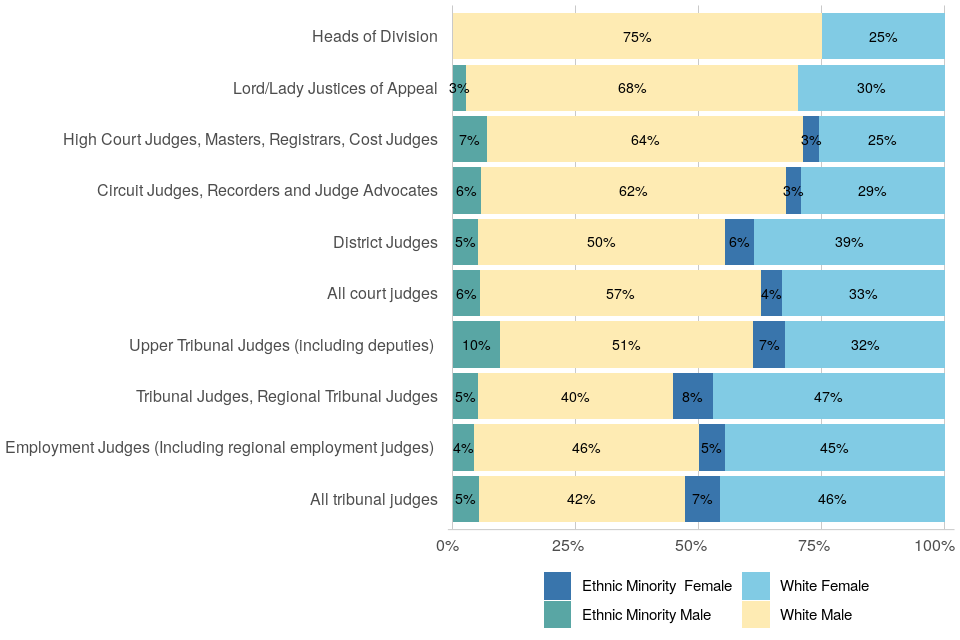

Due to small numbers at a more granular level of ethnic group categorisation, here we only consider the aggregated category overall. The representation of ethnic minority individuals varied with appointment-type, but there was no clear pattern with regards to seniority.

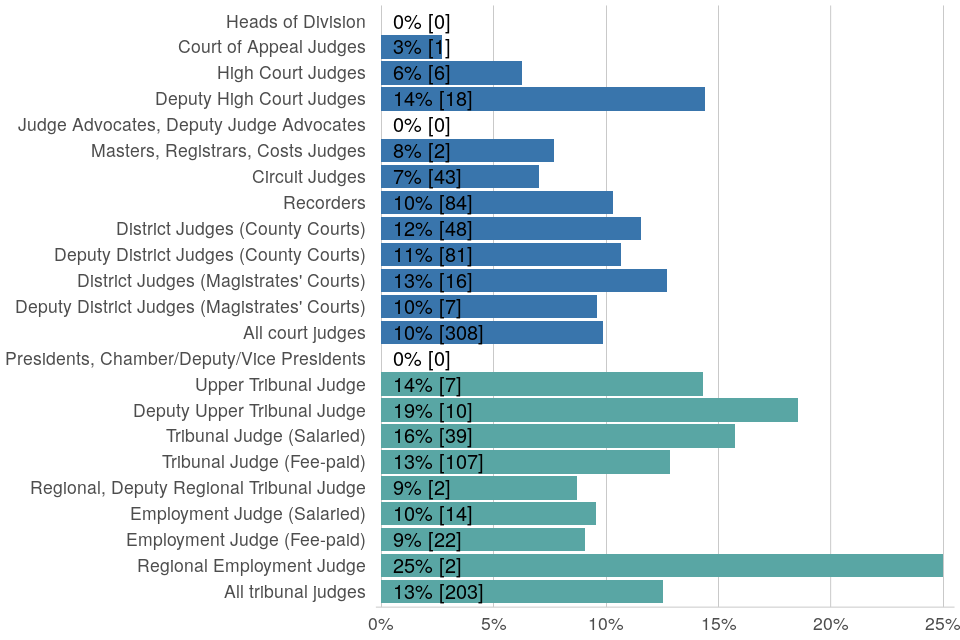

In the courts, the proportion of judges from ethnic minority backgrounds was fairly high for Deputy High Court Judges at 14% (Figure 21) but otherwise generally lower for the more senior appointments.

Ethnic minority representation was generally consistent across tribunal roles, though there were no ethnic minority judges whose primary appointment was in the most senior tribunal positions (Presidents).

Figure 21: Representation of ethnic minority individuals among court and tribunal judges by appointment, 1 April 2023.

Patterns by region

Over half (53%) of all court judges who declared their ethnicity as ethnic minority were based in London, compared to only 2% in Wales and 3% in the South West.

The proportion of ethnic minority court judges also varied by region, from 12% and 13% in London and the Midlands, to 3% in Wales and the South West.

This is likely to reflect, to some extent, variations in the geographic distribution of ethnic minority groups in the general population by region, which is considerably higher in London than other regions.

7. Professional Background

7.1 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

There is evidence of disparity for solicitors compared to barristers in the recommendation rate from application for the legal selection exercises completed during 2022/23.

The professional background of applicants for judicial appointment is analysed using two separate methods:

-

“current legal role” compares applicants who have declared their current legal role as solicitor with those declaring their current legal role as barrister[footnote 28].

-

“ever legal role”[footnote 29] compares those who have ever been a solicitor to those who have ever been a barrister. This includes those who currently hold a legal role of barrister or solicitor and those who have declared holding the role of barrister or solicitor at any stage in their career[footnote 30].

Around 10% more applicants were identified as solicitors using the wider definition of ever legal role, though the same broad patterns are shown for both measures and as a result the focus below is on the “ever legal role”[footnote 31].

Overall 77 applicants (1%) declared holding the role of CILEX professional at application in 2022/23. Eleven of these were shortlisted and four were recommended for immediate appointment. CILEX lawyers are currently eligible to apply for only a limited number of legal exercises and, as such, application numbers are not sufficiently high enough for inclusion in this year’s analysis[footnote 32].

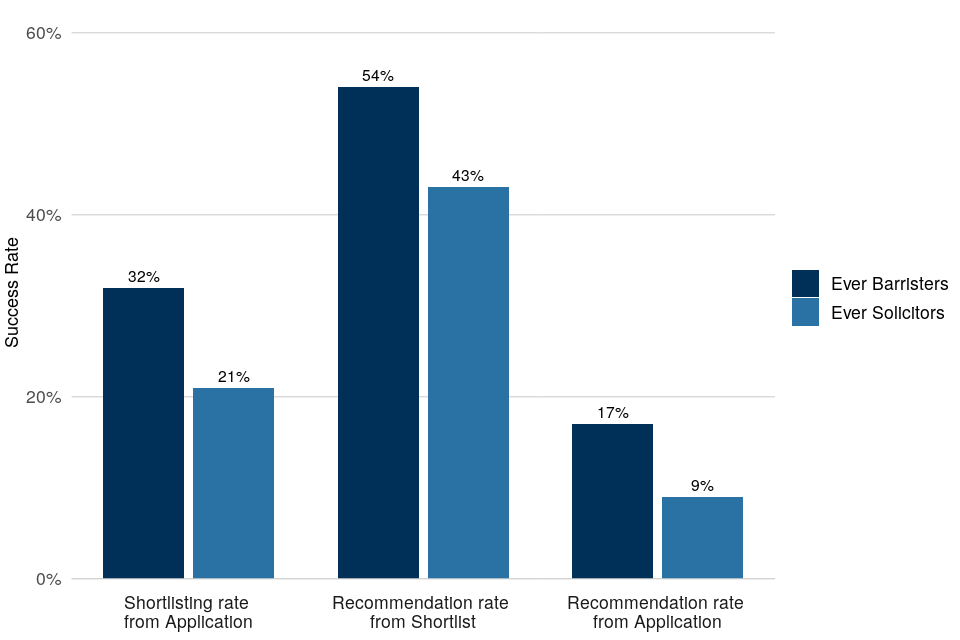

Overall View

Across all legal exercises in 2022-23:

- From application[footnote 33] to recommendation, we can be confident that a disparity of practical significance exists between solicitors and barristers. “Ever” solicitors were 46% less likely to be successful than “ever” barristers (shown by the statistically significant RRI of 0.54; for current solicitors relative to current barristers, the equivalent RRI is 0.51)[footnote 12].

- “Ever” solicitors made up 44% of the recommendations for appointment (compared to 56% for “ever” barristers). For current solicitors, the equivalent figure was 35% (compared to 50% for barristers and 14% for other roles).

- This disparity can be further understood by considering the lower progression rates from application to shortlisting and shortlisting to recommendation for “ever” solicitors compared to those for “ever” barristers (Figure 22). A similar pattern exists for the current legal role measure.

Figure 22: Progression of applicants through the exercise stages by “ever legal role” (all legal exercises completed in 2022-23)[footnote 34].

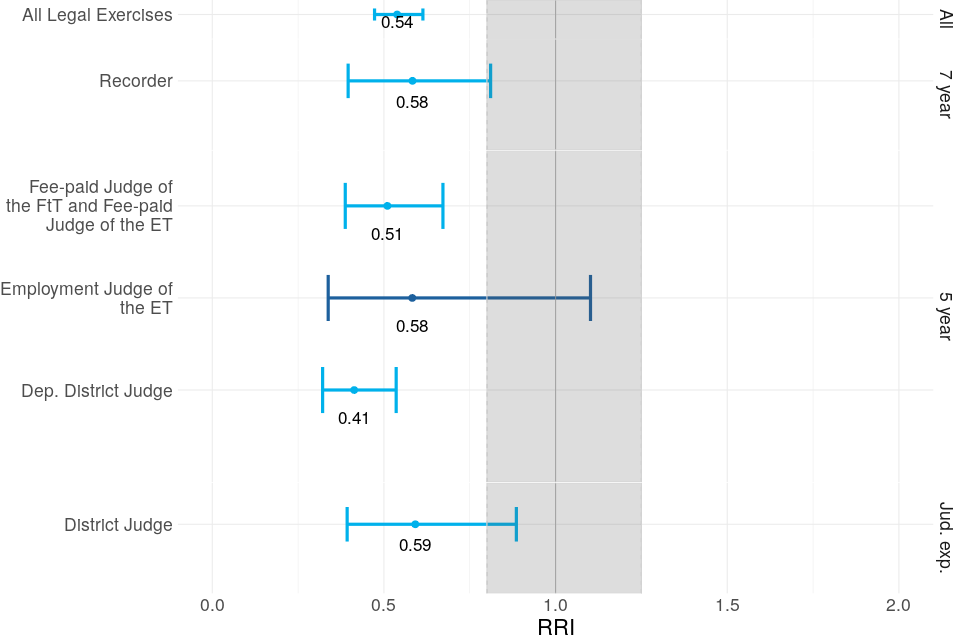

Exercise-specific Analysis

Considering the results for individual exercises:

- For four of the five legal selection exercises large enough to reliably calculate an RRI, there was evidence of a disparity in success rates from application to recommendation for “ever” solicitors compared to “ever” barristers, which were both practically and statistically significant (Figure 23). For the remaining exercise the difference was not statistically significant, which implies no evidence for disparity in the recommendation rate.

- Figure 24 shows that for two of the ten legal exercises completed in 2022/23, District Judge and District Judge (Magistrates’ Court), there was a higher representation of “ever” solicitors at the recommendation for appointment stage compared to the eligible pool stage.

- For three of the four roles requiring previous judicial experience (District Judge Magistrates’ Court, High Court Judge and S9(1) authorisation), solicitors made up a higher percentage of recommendations than applications, indicating strong performances from solicitor background candidates in those more senior exercises.

Figure 23: RRI for “ever” solicitors compared to “ever” barristers, from application to recommendation (large legal exercises completed in 2022-23).

For the above figure note that statistically significant results – where the confidence interval (represented by the arms extending from each dot) does not overlap the parity line (1 on the x-axis) - are light blue. The tolerance zone is shaded grey (0.8 to 1.25); results falling within this zone are considered to represent a disparity which is not large enough to be considered practically important (and tend not to be statistically significant).

Figure 24: Representation of “ever” solicitors at different exercise stages, by eligible pool type (large legal exercises completed in 2022-23).

7.2 Judicial Office Holders

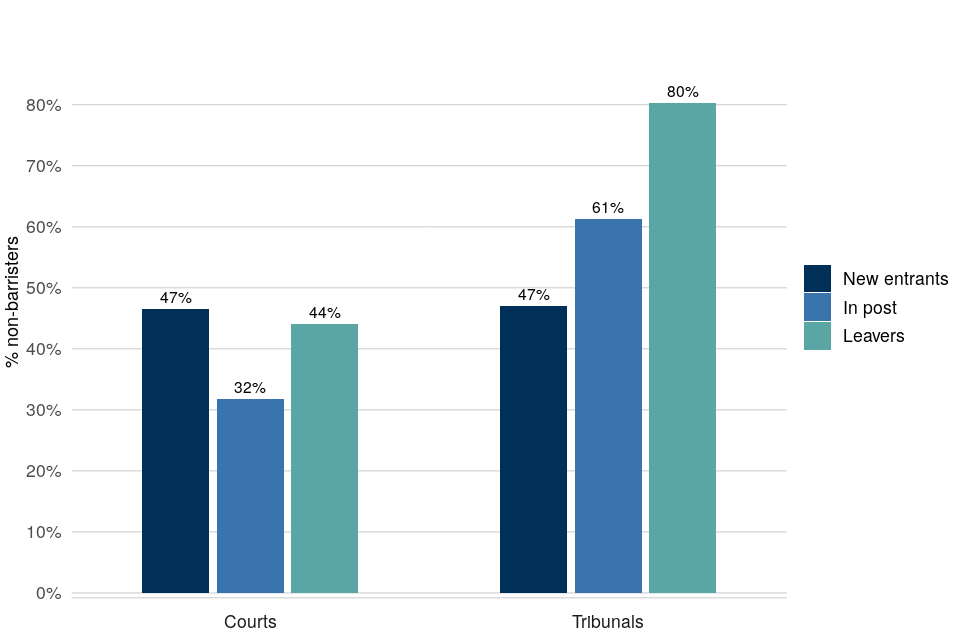

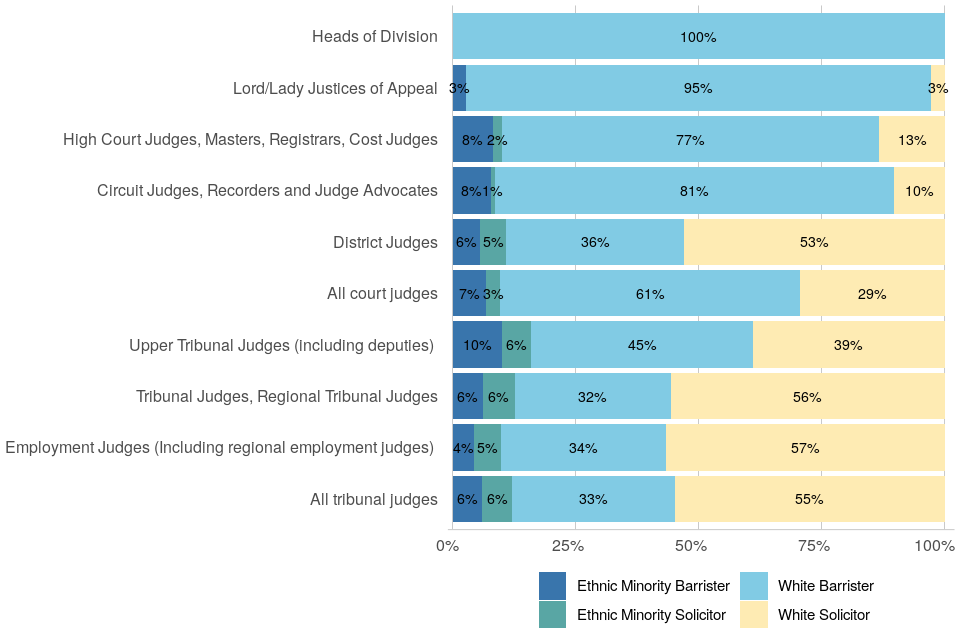

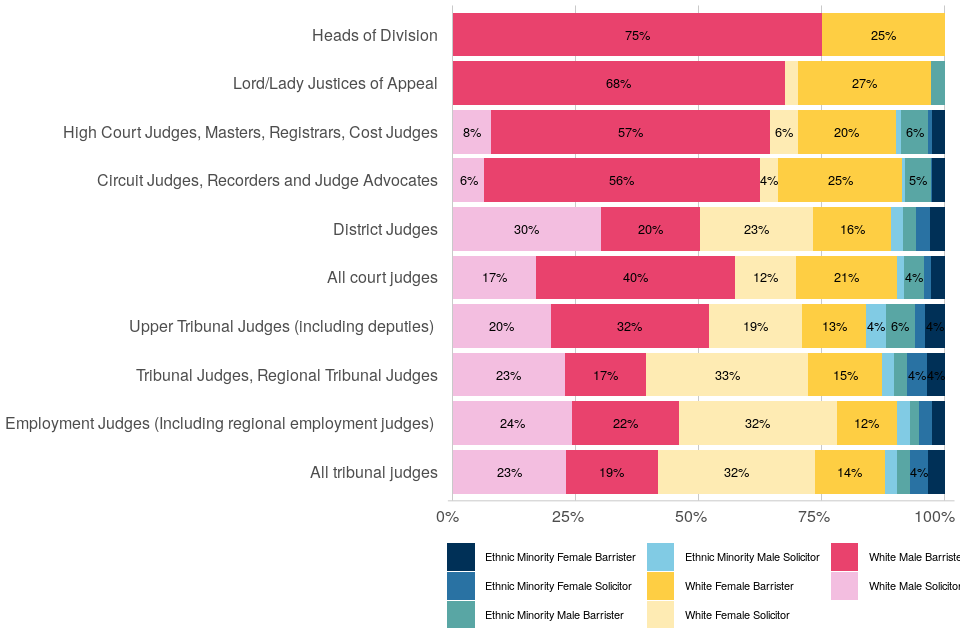

Tribunal judges are twice as likely to have a non-barrister background than court judges.

Judges in post

As at 1 April 2023:

- the vast majority of judges from a non-barrister background were former solicitors (98%) with only 46 judges coming from neither a barrister nor a solicitor background.[footnote 35]

- non-barristers remain better represented among tribunal judges, though non-barrister representation has been reducing gradually over time in both courts and tribunals. Non-barristers represented 32% of all court judges and 61% of all tribunal judges. Compared to 2014, this is a 5 percentage-point decrease among court judges, and compared to 2015 a 6 percentage-point decrease among tribunal judges (Figure 25)[footnote 36]

Figure 25: Representation of non-barristers among court and tribunal judges, 2014 to 2023.

Entrants and leavers

A higher proportion of new entrants to the courts judiciary during 2022/23, compared to leavers, were non-barristers (Figure 26), possibly accounting for the small increase in the proportion of non-barrister court judges as at 1 April 2023 compared to 2022 (see Table 3.4). In contrast, the proportion of new entrant tribunal judges who were non-barristers was much lower compared to that for leavers during 2022/23, adding to the continued drop in the proportion of non-barrister tribunal judges seen in 2023.

Table 3.1 shows that the proportion of non-barrister judges in post who were promoted in 2022/23 was the same as that for judges with a barrister background (2%) - although the actual numbers are fairly small and can be affected year-on-year by the mix of roles involved.

Figure 26: Representation of non-barristers among court and tribunal judges leaving and joining the judiciary, 1 April 2022 – 31 March 2023.

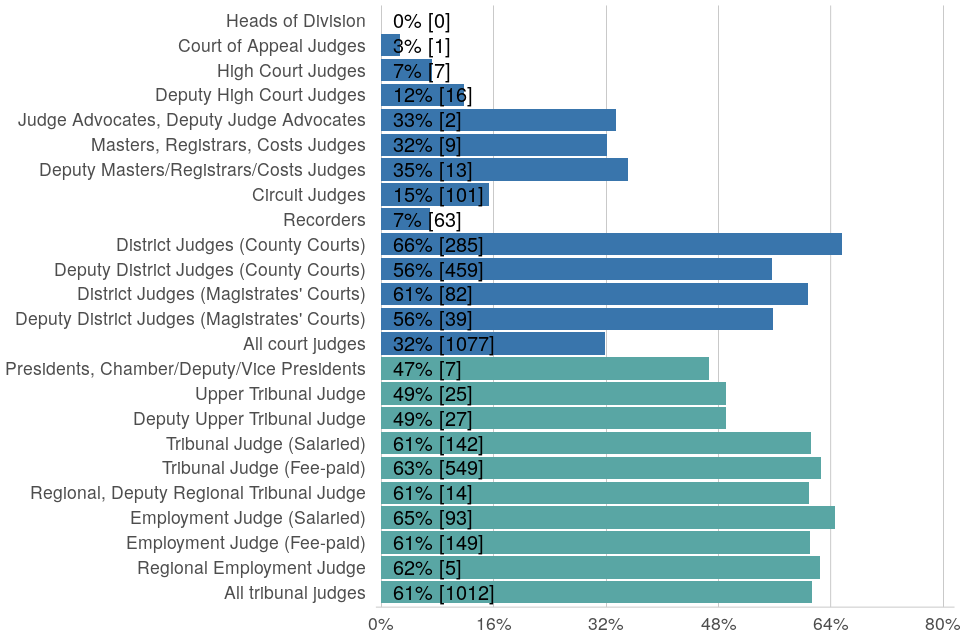

Patterns by type of appointment

Within the courts, non-barristers had a higher representation among the less senior judicial posts. Five percent of all judges in the senior posts (High Court and above) were non-barristers (Figure 27). Conversely, the non-barrister proportion among District Judges and Deputy District Judges was at least 56%.

Within the tribunals, representation of non-barristers was more evenly distributed across the different appointments.

Figure 27: Representation of non-barristers among court and tribunal judges, by appointment, 1 April 2023.

8. Intersectionality

Intersectionality explores the relationship between diversity characteristics. It captures how the combination of multiple characteristics can ‘intersect’ to produce heightened experiences of advantage or disadvantage. Analysis was conducted to explore the role of intersectionality in the legal professions, on judicial appointments, and for judicial office holders.

8.1 Legal Professions

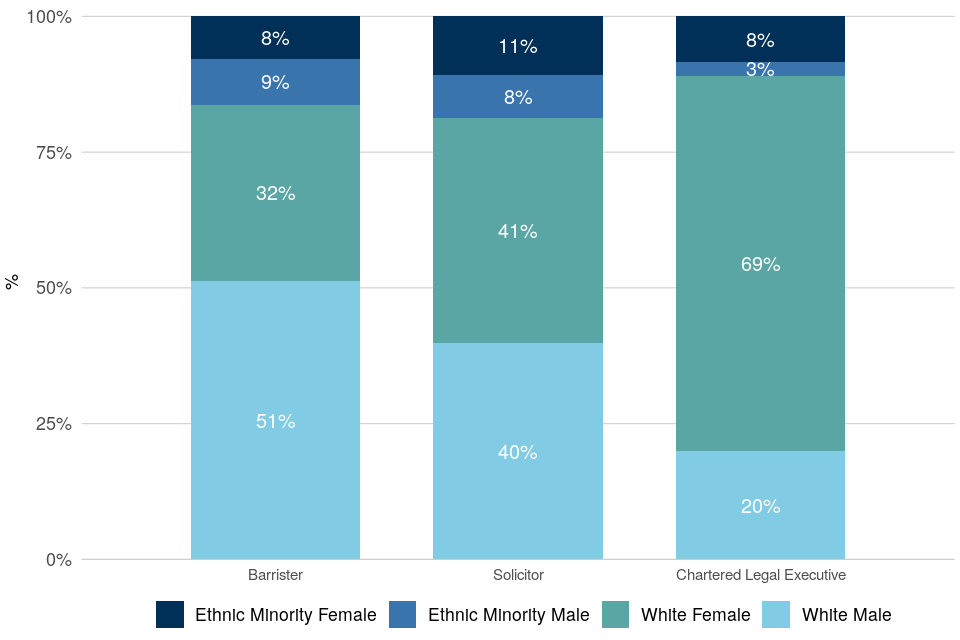

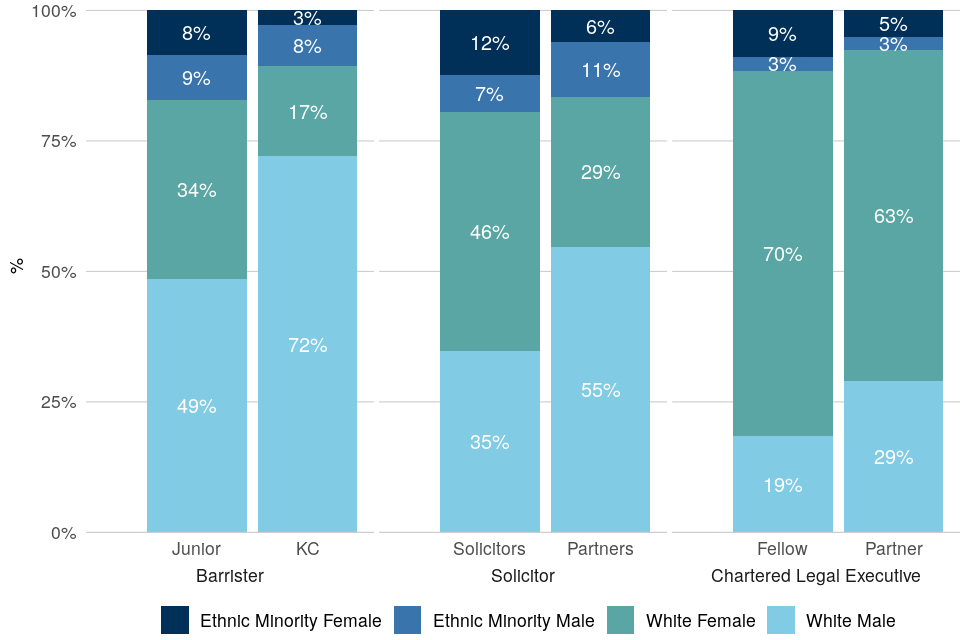

Sex and ethnic group representation varies across the legal professions. For barristers, representation of white men is higher, but white women are more represented among Chartered Legal Executives.

Across each profession overall, Figure 28 shows that as at 1 April 2023, for the four sex-ethnicity intersection groups (white men, white women, ethnic minority men, ethnic minority women):

- White men constituted half of all barristers (51%)

- Of those solicitors who declared, most were equally white men and women (40% and 41% respectively)

- White women made up over two-thirds (69%) of Chartered Legal Executives

When looking specifically at the legal professionals with 15 or more years’ PQE, the distributions are similar, but with slightly higher proportions for white men in all three legal professions.

Figure 28: Representation of sex-ethnicity intersection groups by profession as at 1 April 2023.

Seniority

Both white women and ethnic minority women have lower representation in higher seniority positions in all three legal professions (Figure 29).

White men are the only sex-ethnicity intersection group for which representation is higher in more senior positions in all three legal professions.

Figure 29: Representation of sex-ethnicity intersection groups by profession and seniority as at 1 April 2023

8.2 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

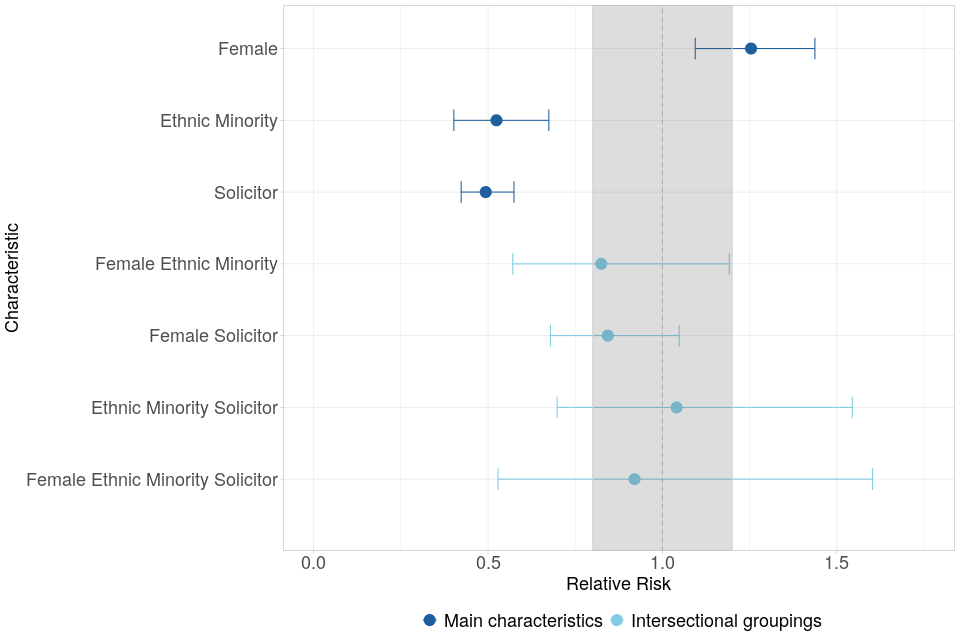

Overall, there is no evidence of intersectional disparity in judicial selection over the period 2020-2023.

Method

The role of intersectionality in judicial appointments was analysed using data from the past three years, that is 2020/21 to 2022/23. The analysis explored the degree to which candidates with multiple minority characteristics faced barriers to recommendation over and above those faced for each individual characteristic on its own. Outcomes for four intersectional groups were considered: female ethnic minority candidates; ethnic minority solicitors; female solicitors; and female ethnic minority solicitors. Each of these groups were compared to white male barristers.

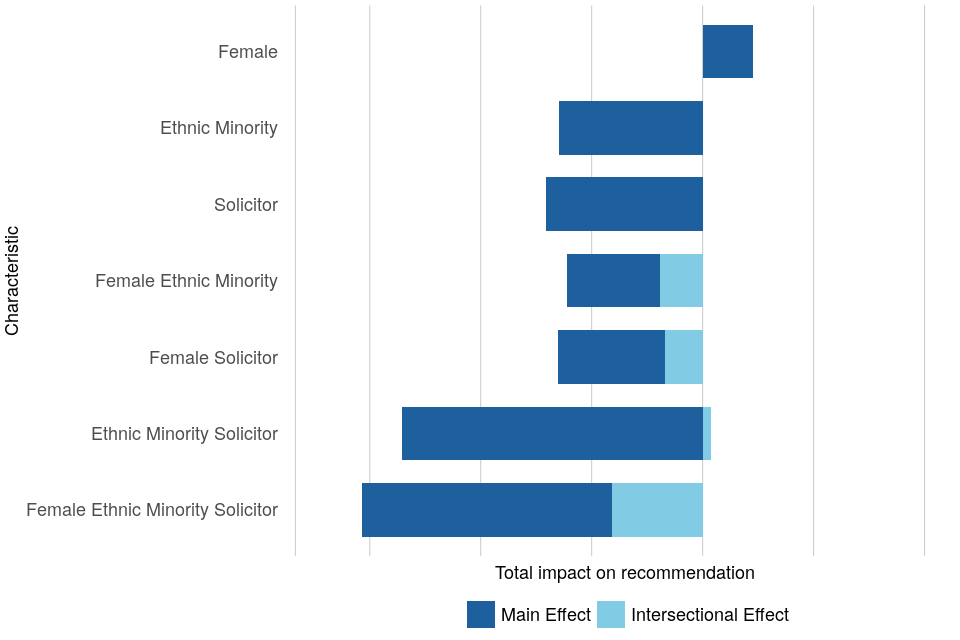

Findings: Main effects

Figure 30 and Table 2.10 show the estimated effect of each main characteristic and intersectional grouping on recommendation. The independent qualities of being female, an ethnic minority, and a solicitor had statistically significant effects on recommendation. In comparison to a white male barrister, being female was associated with a 25% increase in the odds, or risk, of being recommended and being an ethnic minority or a solicitor was associated with a 48% and 51% decrease in the odds of being recommended, respectively. Unlike when RRIs are calculated directly for each characteristic in previous chapters, this analysis isolates the impact of each characteristic once having accounted for the others. The impacts of ethnicity and professional background remain largely in line those produced by RRIs, but the impact of sex increases. In other words, once the negative impacts of being an ethnic minority or a solicitor have been accounted for, being female is associated with a 25% increase in the odds of appointment.

Findings: Intersectional effects

Having accounted for main effects, any additional barriers posed by intersectionality were isolated. Being a female ethnic minority, a female solicitor, or a female ethnic minority solicitor was associated with a small decrease in the odds of being recommended, over and above the main impacts of being female, an ethnic minority, or a solicitor. Contrastingly, being an ethnic minority solicitor was associated with a very small increase in the odds of being recommended. However, none of these effects were statistically significant, meaning that there was no significant evidence of intersectional effects. Put differently, this analysis implies that there is no additional advantage or disadvantage in judicial appointment for having combined characteristics.

Figure 30: Independent impact of main and intersectional characteristics on recommendation (legal exercises completed between 2020 and 2023).

Figure 31 further illustrates this finding by combining main and intersectional effects. The scale used to combine effects differs from relative risk and is not naturally interpretable, and therefore Figure 31 is presented without an x-axis. For each group, the graph captures how much of the total impact on recommendation is driven by main characteristics, and how much is driven by intersectionality. It shows how for candidates with multiple minority attributes, recommendation is largely explained by the effects of each main characteristic, rather than their intersectional effect.

Figure 31: Combined impact of main and intersectional characteristics on recommendation (legal exercises completed between 2020 and 2023).

Significance explanation

Why do we say that there is no significant evidence of intersectionality, despite reporting small associations?

When measuring intersectionality, we calculate the associated effect of each grouping on the likelihood of recommendation, in comparison to white male barristers:

- Female ethnic minorities: 18% decrease in the odds of recommendation.

- Female solicitors: 4% increase in the odds of recommendation.

- Ethnic minority solicitors: 16% decrease in the odds of recommendation.

- Female ethnic minority solicitors: 8% decrease in the odds of recommendation.

We then calculate a confidence interval around each effect to reflect the fact that, if the same exercises were run again, outcomes might vary. The confidence interval gives us a range where we would expect to find the effect of each characteristic, or combination thereof, the next time their impact is assessed.

- Female ethnic minorities: Effect ranges from 43% decrease to 19% increase in the odds of recommendation.

- Female solicitors: Effect ranges from 30% decrease to 54% increase in the odds of recommendation.

- Ethnic minority solicitors: Effect ranges from 32% decrease to 5% increase in the odds of recommendation.

- Female ethnic minority solicitors: Effect ranges from 47% decrease to 60% increase in the odds of recommendation.

For all four groups, the confidence interval crosses the 1.0 line, meaning that 0% is included in the range of possible effects on recommendation. This is shown in Figure 30, where the confidence intervals for the four intersectional effects cross the 1.0 line, but for the main effects do not. Given this, we cannot conclude that there is a statistically significant difference in recommendation rates between intersectional and non-intersectional candidates. For this reason, we conclude that there is no additional advantage or disadvantage in judicial appointment for having combined characteristics.

8.3 Judicial Office Holders

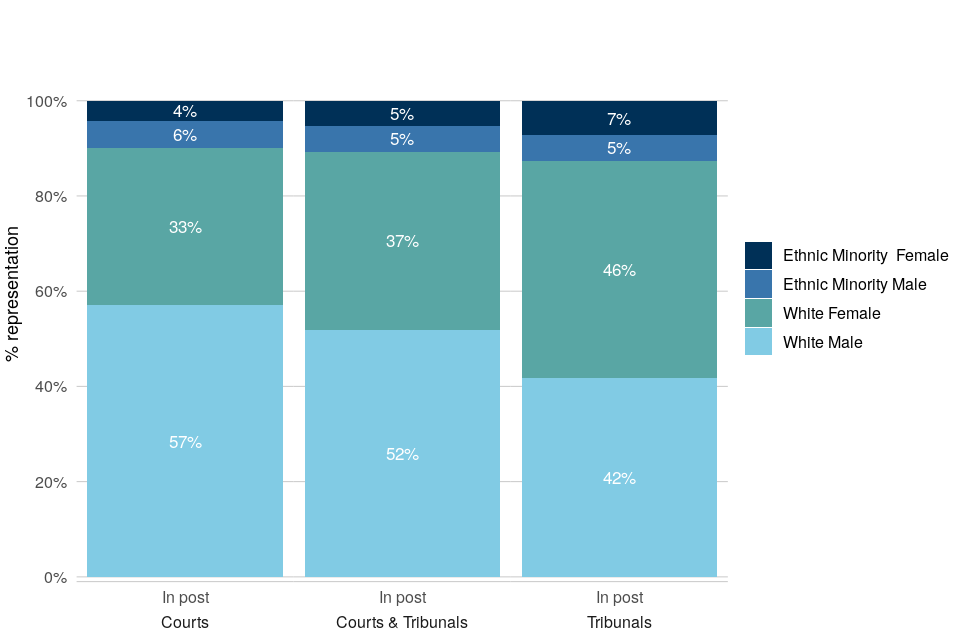

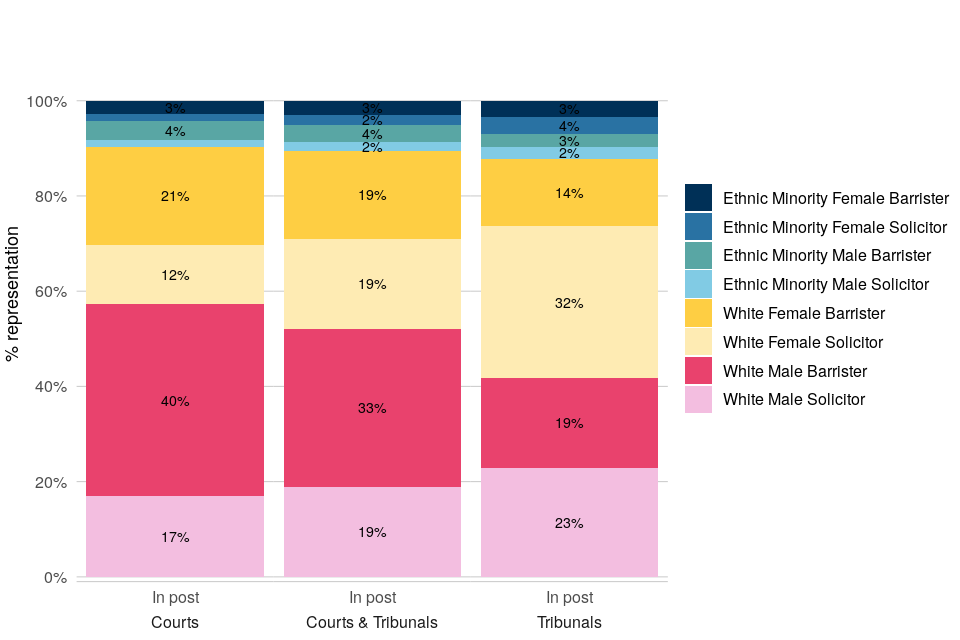

More than half of the judiciary are white men and over a third are white women. Ethnic minority men and women each account for one in twenty judges.

White male barristers are the largest sex-ethnicity-profession group in the judiciary and occupy most of the senior court posts.

Sex and Ethnicity

Judges in post

As at 1 April 2023, white men made up more than half (52%) of all court and tribunal judges (Figure 32).

White and ethnic minority women constituted a higher proportion of tribunal judges (46% and 7%) compared to court judges (33% and 4%).

Figure 32: Representation of different sex-ethnicity groups in judges in post, April 2023

Patterns by type of appointment

A substantial majority of senior court judicial posts (High Court and above) are held by white men (Figure 33). Tribunal posts tend to have higher proportions of white women and ethnic minority women than court posts.

Figure 33: Representation of sex-ethnicity groups by primary appointment, April 2023

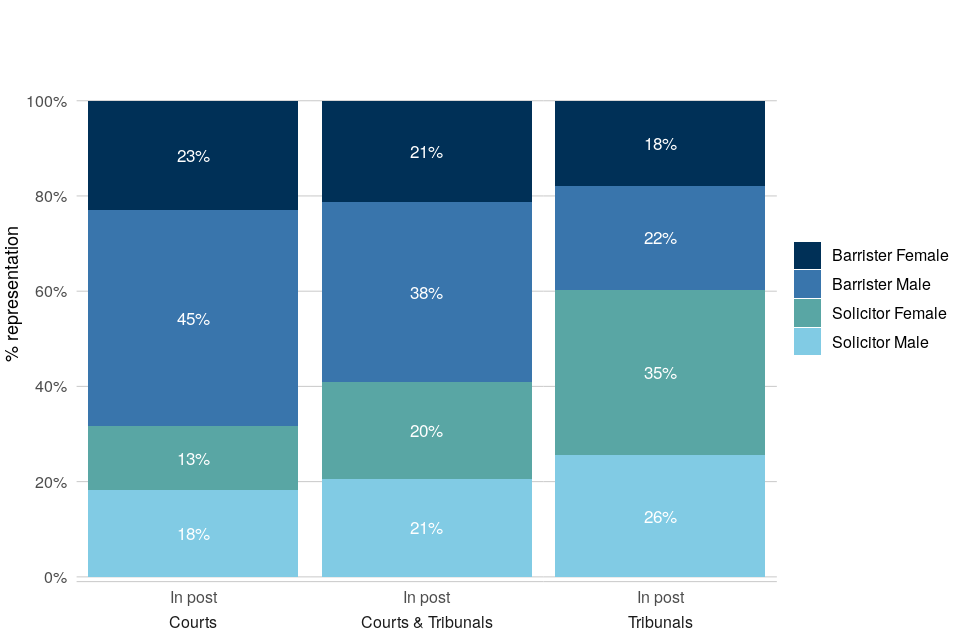

Sex and Professional Background

Judges in post

As at 1 April 2023, men with barrister professional backgrounds constituted 38% of all judges, and nearly half (45%) of all court judges[footnote 37] (Figure 34).

Considerably more tribunal judges were women with solicitor professional backgrounds (35%) compared to court judges (13%)

Figure 34: Representation of different sex-profession groups in judges in post, April 2023

Patterns by type of appointment

The sex split amongst former barristers is more even among tribunal judges (22% male:18% female) compared to court judges (45%:23%). However, the sex split amongst former solicitors is greater among tribunal judges (26% male:35% female) compared to court judges (18%:13%).

Figure 35: Representation of sex-profession groups by primary appointment, April 2023

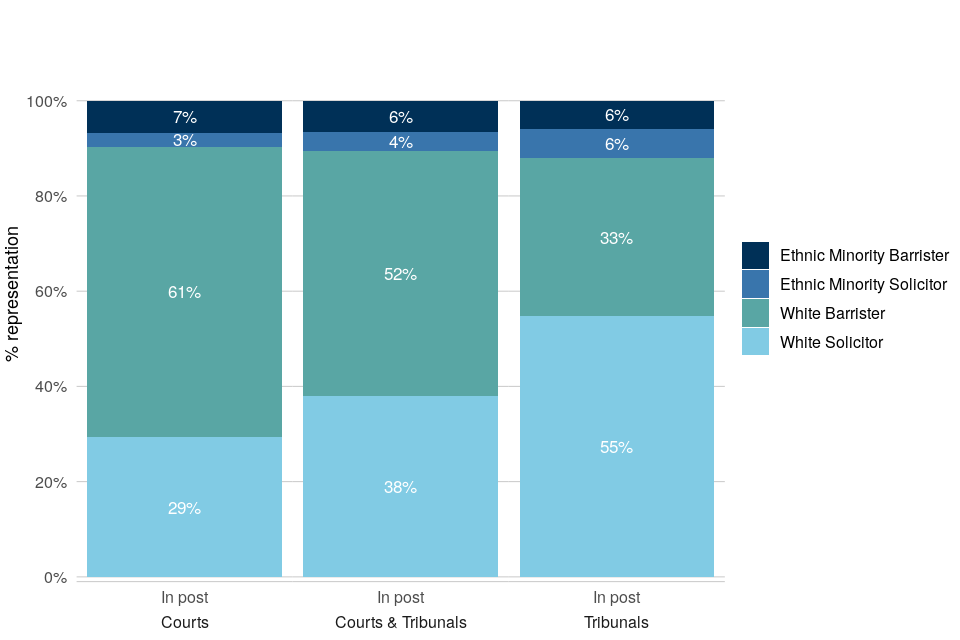

Ethnicity and Professional Background

Judges in post

As at 1 April 2023 white individuals with barrister professional backgrounds made up over half (52%) of all judges (Figure 36).

Ethnic minority and white individuals with solicitor professional backgrounds constituted proportionally nearly twice as many tribunal judges (6% and 55%) as they did court judges (3% and 29% respectively).

Figure 36: Representation of different ethnicity-profession groups in judges in post, April 2023

Patterns by type of appointment

Almost all of the senior court judicial posts (High Court and above) are held by white former barristers. White barristers represented 61% of all court judges but only 33% of all tribunal judges.

Figure 37: Representation of ethnicity-profession groups by primary appointment, April 2023

Sex, Ethnicity and Professional Background

Judges in post

As at 1 April 2023 white men with barrister professional backgrounds constituted a third of all judges overall (Figure 38).

Most of the remainder constituted white men with solicitor professional backgrounds and white women with barrister or solicitor professional backgrounds, who each made up just under a fifth (19%) of all judges.

Figure 38: Representation of different sex-ethnicity-profession groups amongst judges in post, April 2023

Patterns by type of appointment

Four of every ten court judges are white male former barristers, whilst white women with solicitor professional backgrounds make up around a third (32%) of tribunal judicial posts.

Figure 39: Representation of sex-ethnicity-profession groups by primary appointment, April 2023

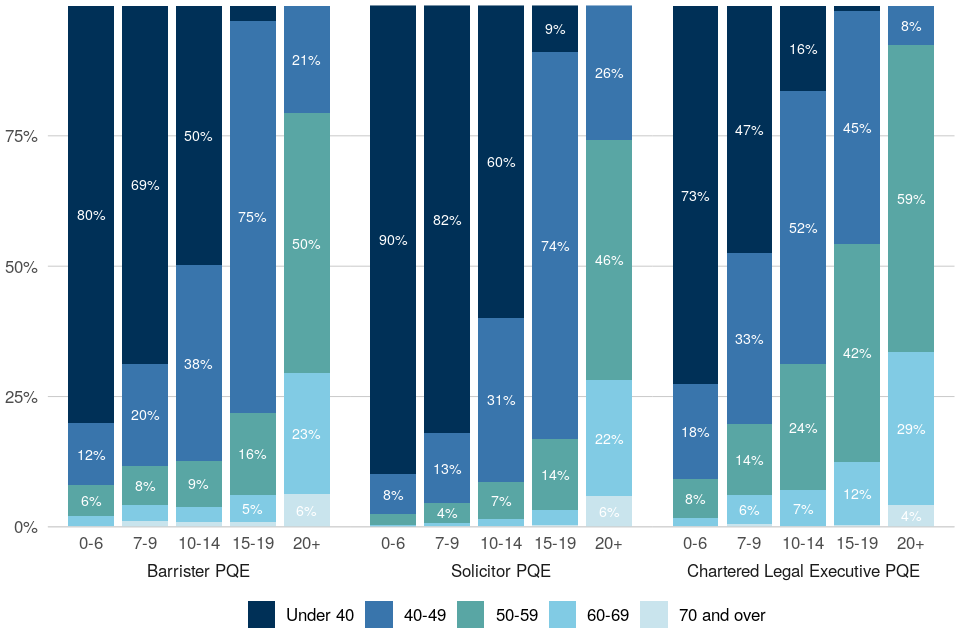

9. Age

9.1 Legal Professions

As at 1 April 2023, 39% of barristers, 30% of solicitors and 39% of Chartered Legal Executives were aged 50 or over.

Post Qualification Experience

Predictably, post qualification experience in legal professionals is strongly associated with age (Figure 40). As at 1 April 2023, of those with 15 or more years’ experience, 65% of barristers, 56% of solicitors and 76% of Chartered Legal Executives were aged 50 and over.

Figure 40: Age group for different levels of post-qualification experience in the legal professions, April 2023.

Seniority

As would be expected a higher proportion of those in more senior roles are aged 50 or over, compared to those in less senior positions:

- for barristers, 79% of KCs, compared with 35% of junior barristers

- for solicitors, 51% of partners compared with 25% of solicitors

- for Chartered Legal Executives, 53% of partners compared with 37% of fellows

9.2 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

Older applicants have lower recommendation rates than younger applicants, with 72% of new appointees aged under 50.

Age is strongly correlated with experience and, as a result, it is less insightful to make comparisons between recommendation rates based on age than for other characteristics. Although figures are broken down by age group, we do not conduct relative comparisons of rates of recommendation.

Overall View

Overall, the representation of candidates aged over 50 in legal exercises completed in 2022/23 at application was 39%. This decreased between application and shortlisting to 34%, and then from shortlisting to recommendation for appointment to 28%, and meant that 72% of new appointees were aged under 50.

Exercise-specific Analysis

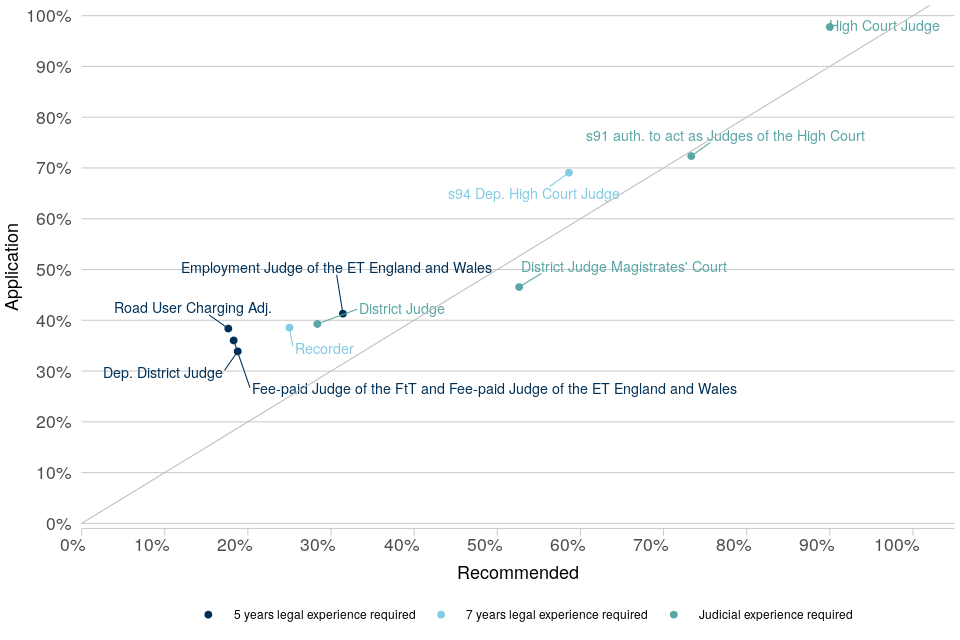

More senior roles typically require greater experience and therefore older age groups are more highly represented at both application and recommendation for appointment stages (Figure 41).

The proportion of individuals aged 50 and over tends to decrease between the application and recommendation for appointment stages, though this was not the case for every exercise. The proportion of applications and recommendations who are aged 50 and over broadly increases with seniority of post. However, exercises where representation of those aged over 50 decreased from application to recommendation are those shown above and to the left of the diagonal line in Figure 41.

Figure 41: Proportion of applications and recommendations aged 50 and over for each large legal exercise in 2022/23, color coded by years of experience required per exercise.

9.3 Judicial Office Holders

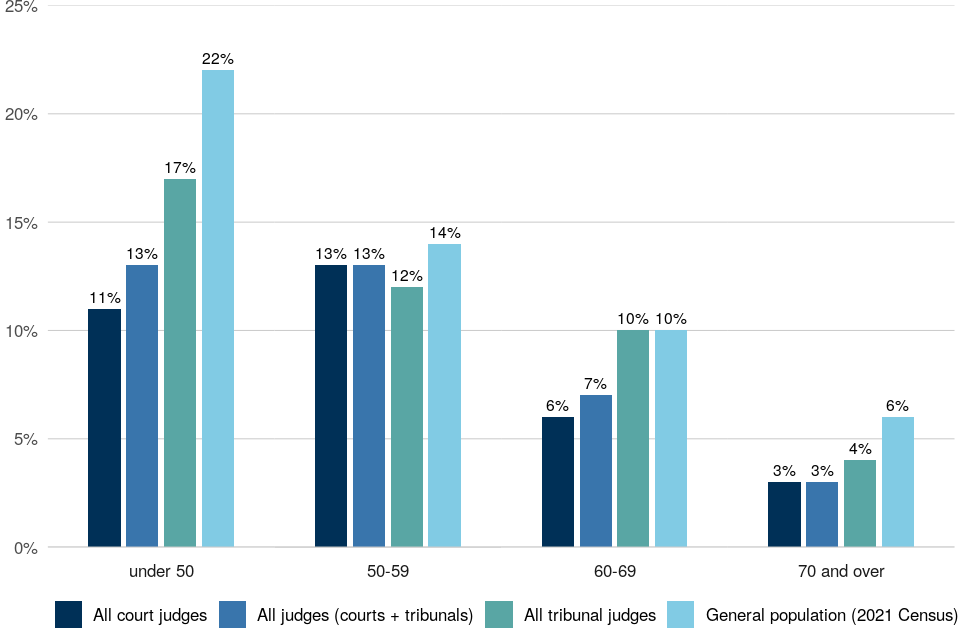

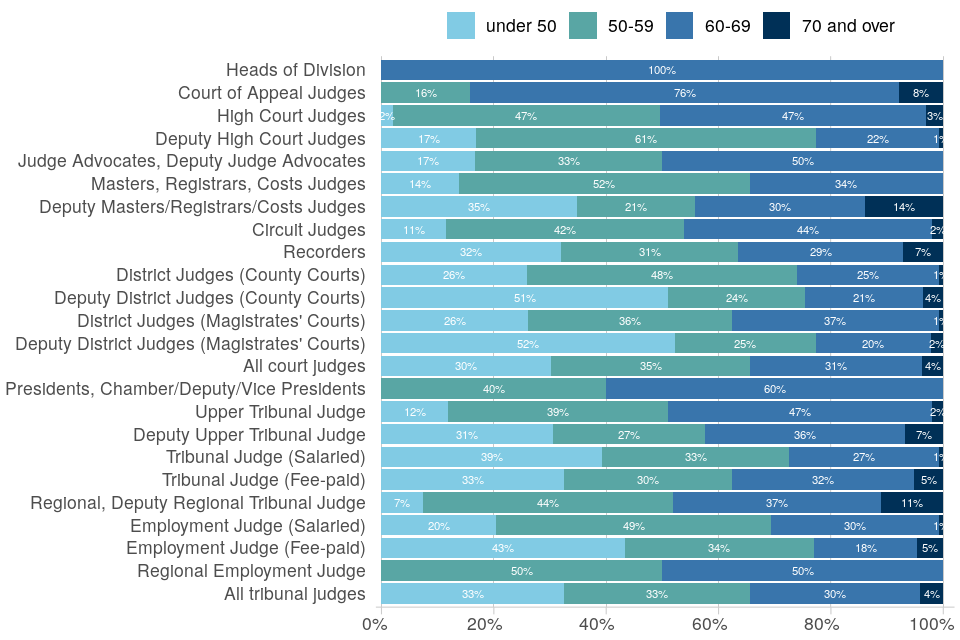

Most court and tribunal judges are aged 50 and over, with 4% aged 70 and over.

Judges in post

As at 1 April 2023, over two-thirds of judges were aged 50 and over - with similar proportions in the courts (70%) and tribunals (67%). In courts and tribunals 4% of judges were aged 70 and over[footnote 38].

Entrants and Leavers

Not unexpectedly, for judges in both courts and tribunals three-quarters of new entrants to the judiciary in 2022-23 were aged under 50, whilst the majority (93%) of those leaving the judiciary were aged 50 and over.

Patterns by type of appointment

Predictably for courts and tribunals, the proportion of those in the older age groups was generally higher among more senior posts (Figure 42).

Figure 42: Representation of ages 50 and over among court and tribunal judges by appointment, 1 April 2023.

10. Other Characteristics

10.1 Judicial Appointments: Applications and Selections

Disability: For legal exercises overall, candidates with a disability had a marginally higher recommendation rate from application than candidates without a disability.

Social mobility: Across all legal exercises, candidates who attended a UK state school had a slightly lower recommendation rate from application compared to those who attended a UK independent or fee-paying school.

Sexual orientation: Across all legal and non-legal exercises combined, candidates who identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual had a slightly higher recommendation rate from application than candidates who were heterosexual.

This section presents available statistics for other diversity characteristics – disability, social mobility, religion, and sexual orientation. Currently these are only collected in a sufficiently robust way for judicial selection, and not for judges in post or the legal professions. This means we cannot provide analysis of recommendation rates compared to the eligible pools, as produced for other characteristics. A summary is presented here, with further details in the accompanying data tables.

Disability

Across all legal exercises in 2022-23, candidates with a disability represented 9% of both applications and all recommendations made, leading to a marginally higher recommendation rate from application (13%) compared to candidates without a disability (12%)[footnote 39].

Social Mobility

For all legal exercises in 2022-23, individuals who attended a UK state school had a slightly lower recommendation rate from application (12%) compared to those who attended a UK independent or fee-paying school (15%). Those who attended a UK state school made up 73% of applications and 71% of recommendations.

Almost all (99%) applicants attended university. Applicants who were the first generation in their family to attend university (i.e. neither of their parents attended university) had a lower recommendation rate from application (11%) compared to candidates who were not the first generation to attend (16%)[footnote 40].

Sexual Orientation[footnote 41]

Across all exercises (legal and non-legal) in 2022-23 combined, candidates who declared themselves to be lesbian, gay, or bisexual represented 6% of applications and 7% of recommendations made, resulting in a slightly higher recommendation rate from application (16%) compared to those who declared themselves to be heterosexual (14%).

Religion or belief[footnote 42]

For all exercises (legal and non-legal) in 2022-23 combined, the religion or belief with the largest representation among both applications and recommendations was Christian (46% and 45% respectively), followed by individuals who declared no religion or as atheist (34% and 42% respectively).

The recommendation rates from application ranged from 7% for Muslim candidates to 21% for those candidates who declared some other religion or belief, with Christian candidates at 14% and no religion/atheist candidates at 18%.

10.2 Legal Professions and Judicial Office Holders

As at 31 March 2023, while there has been an increase, the disability declaration rates for the judiciary was not at the 60% level required for statistical confidence in presenting data on judges with a disability.[footnote 43]

The Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) have reported that 1.4% solicitors have declared a disability on their individual accounts with the SRA, but legacy data issues mean they are unable to confirm with any confidence the overall declaration rate.

CILEX have reported an 95% declaration rate and that 4.3% of their members have reported a disability. The Bar Standards Board have reported a declaration rate of 62% with 7.8% of their members declaring a disability. The Judicial Appointments Commission reported a 96% declaration rate for all exercises with 9% of those recommended for appointment in 2022-23 reporting a disability.

Given the current declaration rates overall and the different approaches used to collect data, it is not possible to publish or analyse disability data for judges and lawyers in this report. The judiciary are taking action to increase their declaration rates and the SRA are addressing their legacy data issues. The position will be reviewed again ahead of the 2024 report.

11. Judges sitting in retirement

In comparison to judges, a lower proportion of court judges and tribunal judges sitting in retirement are women or from an ethnic minority background, but a higher proportion have a non-barrister background.

Sitting in retirement is the policy which permits certain judges to retire, draw their pension, and continue to sit as a fee-paid judge, if there is a business need to do so, up to the mandatory retirement age of 75.[footnote 44]

There were in total 244 judges sitting in retirement (172 in courts and 72 in tribunals) in England and Wales as at 1 April 2023, with an additional one non-legal tribunal member sitting in retirement (Table 3.5).

11.1 Sex

As at 1 April 2023, women constituted about of fifth (18%) of all court judges sitting in retirement, and nearly half (46%) of all tribunal judges sitting in retirement (Figure 43).

Figure 43: Representation of females among court and tribunal judges sitting in retirement, 1 April 2023.

11.2 Ethnicity

Ethnic minority individuals constituted 4% of all court judges sitting in retirement, and 8% of all tribunal judges sitting in retirement (Figure 44).

Figure 44: Representation of ethnic minorities among court and tribunal judges sitting in retirement, 1 April 2023.

11.3 Professional Background

As at 1 April 2023, non-barristers constituted nearly a half (47%) of all court judges sitting in retirement, and three-quarters (75%) of all tribunal judges sitting in retirement (Figure 45).

Figure 45: Representation of non-barristers among court and tribunal judges sitting in retirement, 1 April 2023.

11.4 Age

Overall, just over half (51%) of all the judges sitting in retirement as at 1 April 2023 were aged 70 or over. However, the proportion was nearly three times higher in the courts (63%) than it was for those in tribunals (22%).

12. Non-legal tribunal members

Compared with judges, a higher proportion of non-legal members are women, or from an ethnic minority background.

There is evidence of disparity for ethnic minority candidates in non-legal selection exercises completed in 2022/23.

Sections 12 to 14 cover roles which do not require a legal background, that is magistrates and non-legal members in tribunals. This compares with preceding sections which focus on legal professions, selections for judicial posts requiring legal experience and judges in post. While non-legal posts typically have eligibility criteria (for example, membership of an appropriate professional body), no attempt is currently made to estimate the eligible pool.

12.1 Appointments for Non-Legal Tribunal Members

Sex

Across all non-legal exercises in 2022/23 women represented a two-thirds of applications (66%) and recommendations (69%), such that their overall success rate was on par with that for men (indicated by the RRI estimate of 1.14 not being statistically significant).

Ethnicity - Single-year Analysis (2022/2023)

Ethnic minority individuals constituted 29% of applications and 19% of the recommendations for all non-legal exercises completed in 2022/23. The likelihood of recommendation from application for ethnic minorities was 42% lower than white candidates, suggesting disparity in recommendation (the RRI estimate of 0.58 was practically and statistically significant).

Ethnicity - Three-year Analysis (2020 to 2023)

In contrast to the latest year, Table 2.7 shows that for those non-legal exercises completed in the last three years, the likelihood of recommendation from application for ethnic minorities was only 6% lower than white candidates (RRI=0.94), suggesting no evidence of disparity for the three-year period.

The likelihood of recommendation from application for black or black British candidates was an estimated 28% lower than white candidates (The RRI of 0.72 was both practically and statistically significant). There was no such disparity for the other three ethnic minority groups.

Age

Across all non-legal exercises overall in 2022/2023 those aged 50 or over accounted for 58% of the applications. This dropped slightly to 56% of those recommended for appointment.

Disability

Candidates who declared themselves to have a disability constituted 11% of the applications and 6% of recommendations for all non-legal exercises completed in 2022/23. As with ethnicity, this suggests evidence of a disparity for disabled candidates relative to non-disabled candidates when comparing recommendation rates from application (indicated by the practically and statistically significant RRI estimate of 0.55).

Social Mobility

Across all non-legal exercises in 2022/2023, candidates who attended a UK state school had a very similar recommendation rate from application compared to those who attended a UK independent or fee-paying school.

Only 5% of applicants had not attended university. Of those who had attended university, those who were the first generation to do so had a slightly higher recommendation rate from application (34%) than those candidates who were not first-generation attendees (29%).[footnote 45]

12.2 Non-Legal Tribunal Members in post

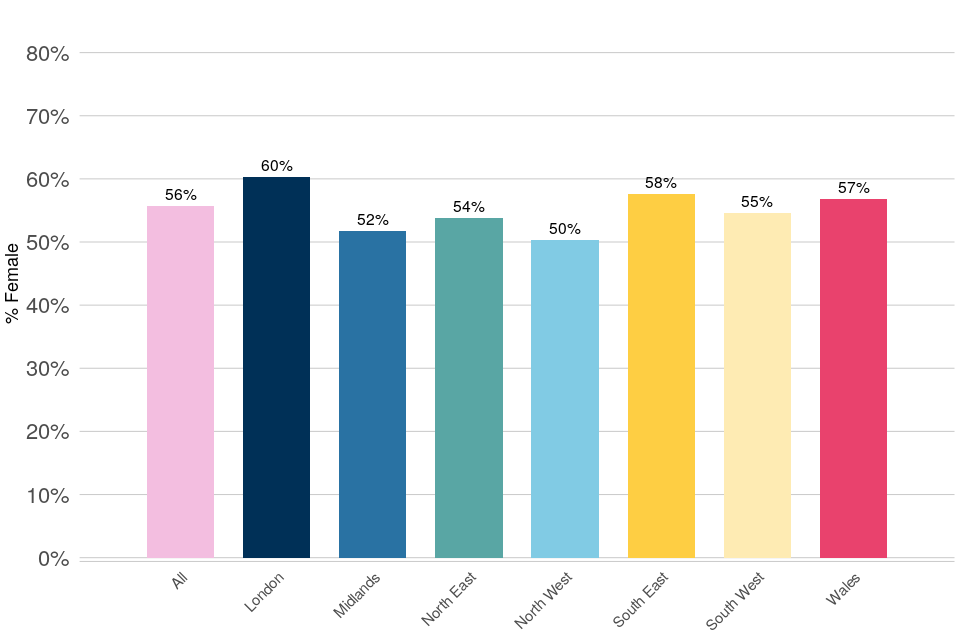

Sex

Women represented over a half (56%) of all non-legal members of tribunals as at 1 April 2023, compared with 42% for all judges. As with the judges, the proportion has been increasing over the past ten years (see Table 3.4).

This is partly reflected in the slightly higher proportion of men non-legal members who left during 2022/23 (7%) compared to women non-legal members (6%).

Ethnicity

As at 1 April 2023 ethnic minority individuals represented a higher proportion (18%) of non-legal tribunal members, compared to that for all judges (11%). Similar to sex, these have been gradually increasing over the last decade.

Again, this is partly reflected in the slightly higher proportion of white non-legal members who left during 2022/23 (6%) compared to ethnic minority non-legal members (5%).

Those of an ethnic minority background were twice as likely to be a medical tribunal member compared to white colleagues, but half as likely to be a disability tribunal member.

Intersection of Sex and Ethnicity

White men constituted a third of all non-legal tribunal members as at 1 April 2023, compared to over half of all judges. Ethnic minority men made up twice as many (10%) non-legal members as they did the judiciary (5%).

The white and ethnic minority women groups also represented a higher proportion of non-legal members than they did of all judges (see Table 3.3).

Age

Non-legal members tended to be older than judges on average, with 84% of those in post being 50 and over, compared to the 69% for all judges.

During 2022/23, for non-legal member posts in tribunals, over half (61%) of new entrants and most leavers (83%) were aged 50 and over.

13. Magistrates

13.1 Magistrates in Post

In comparison to judges, a higher proportion of magistrates are women, or from an ethnic minority background.

Sex

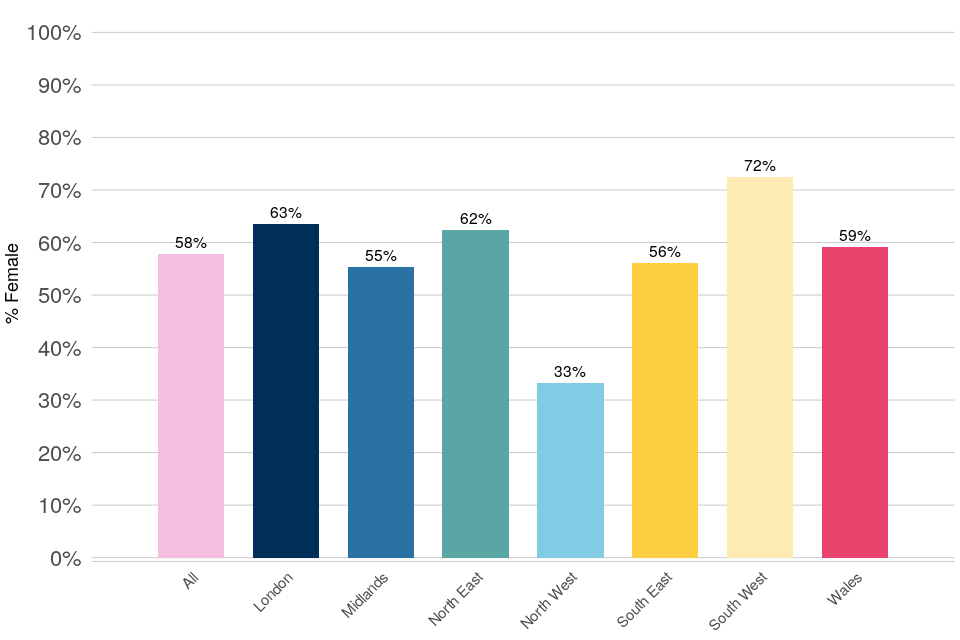

As at 1 April 2023, women represented 57% of all magistrates (five percentage points higher than in 2014). There was no strong variation amongst the regions, ranging from 52% to 60% (Figure 46).

Figure 46: Representation of women among magistrates by region, 1 April 2023

Ethnicity

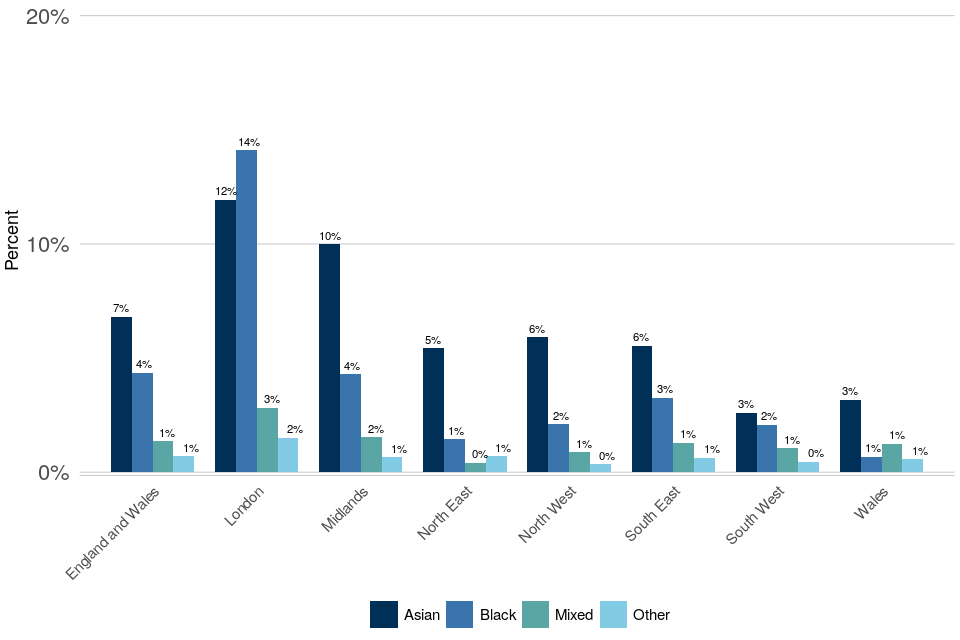

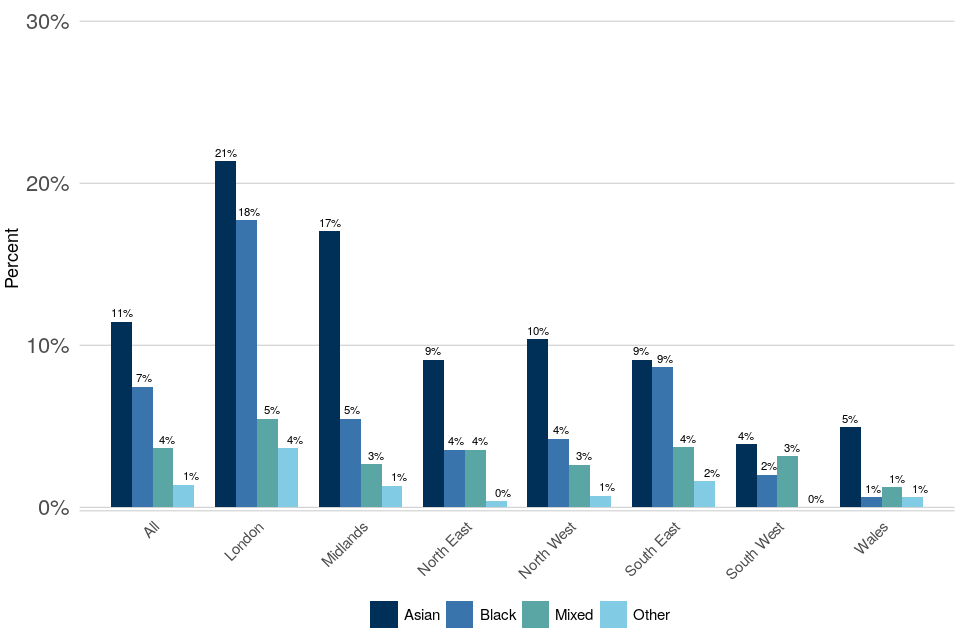

As at 1 April 2023, ethnic minority individuals together constituted 13% of all magistrates (a five percentage-point increase from 2014 when 8% declared themselves as from an ethnic minority). More specifically:

- Asian or Asian British individuals constituted 7% of magistrates.

- Black or black British individuals constituted 4% of magistrates.

- Mixed ethnicity individuals constituted 1% of magistrates.

- Individuals from other ethnicities constituted 1% of magistrates.

These proportions showed some variation at a regional level, where London had at least double the proportion of Asian individuals compared to all but one of the regions, and at least treble the proportion of black individuals compared to all other regions (Figure 47).

Figure 47: Representation of ethnic minorities among magistrates by region, 1 April 2023

Intersection of Sex and Ethnicity

Table 3.7 shows that white women represented just under half (49%) of all magistrates as at 1 April 2023. This was followed by white men with 38%, and then ethnic minority women and ethnic minority men (8% and 6% respectively).

Age

Magistrates tended to be older than judges on average, with 82% of those in post being 50 and over.

13.2 Magistrates - leavers and new entrants

The proportion of magistrates that left during 2022/23 who were female (51%) or of an ethnic minority background (11%) were both lower than the equivalent proportion of new entrants in 2022/23, at 58% and 15% respectively.

14. Magistrates Recruitment[footnote 46]

On 17 January 2022, an updated magistrates’ recruitment process was launched. This update introduced a new applicant tracking system (ATS) which collects information on magistrate recruitment across England and Wales and includes more diversity data on applicants and recommendations for appointment to the magistracy.

Because data from the ATS has not yet been published, this year’s bulletin includes data from 17 January 2022 to 31 March 2023. This ensures that all new ATS data is reported. In future years, ATS data will be published for the previous twelve months only (April to March).

The information in this bulletin is being published in addition to the annual publication of data on new appointments and current post holders.

For women, the proportion applying to join the magistracy is comparable to those already in post, but for ethnic minority individuals it is considerably higher for applicants than for those in post.

14.1 Applications

Table 3.8 shows that between 17 January 2022 and 31 March 2023, there were 5,953 applications made to become a magistrate[footnote 47].

Sex

Women represented 56% of all magistrate applications submitted in 2022-23[footnote 48], with the variation by region (Figure 48) similar to that seen for magistrates in post.

Figure 48: Representation of women among magistrate applications submitted in 2022-23, by region

Ethnicity

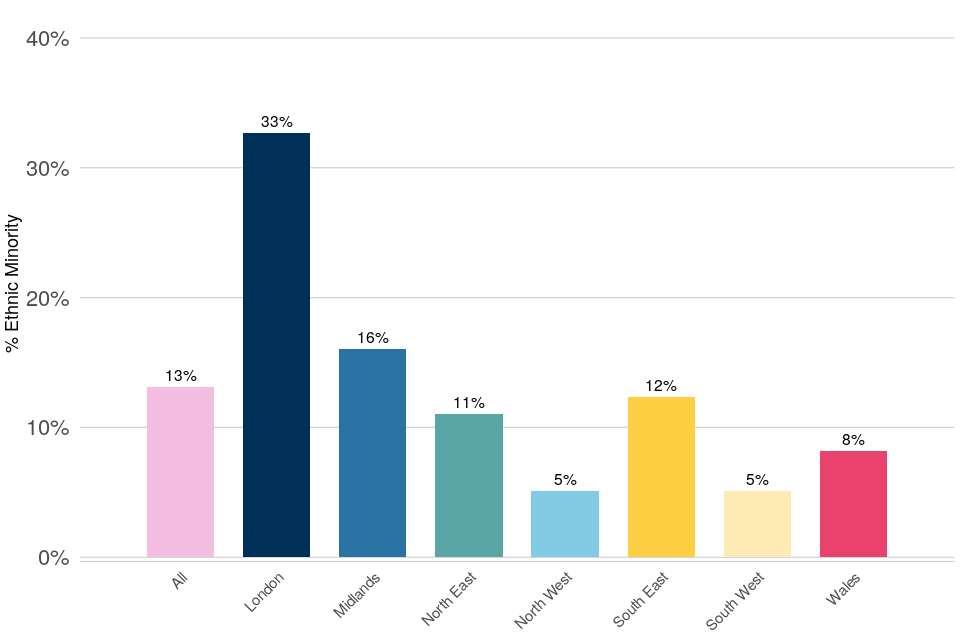

In total, ethnic minority individuals constituted 24% of all magistrate applications submitted in 2022-23. Again, variation by region (Figure 49) was similar to that seen for magistrates in post, except that for applications in London the proportion of Asian individuals was higher than for those with a black ethnic minority background. More specifically:

- Asian or Asian British individuals constituted 12% of applications.

- Black or Black British individuals constituted 7% of applications.