Part B: Absolute grounds for refusal

Includes chapters on definition of a design, novelty and individual character, technical function, morality and emblems.

2.01

Section 1 of the RDA provides a definition of what constitutes a design:-

| Section 1 states: |

| (1) A design may, subject to the following provisions of this Act, be registered under this Act on the making of an application for registration. (2) In this Act “design” means the appearance of the whole or a part of a product resulting from the features of, in particular, the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture or materials of the product or its ornamentation. |

In the context of Section 1, the following paragraphs provide standard information on various elements of design which may be suitable for protection under the RDA, and which are specifically listed in the aforementioned provisions.

2.02

‘Appearance’ essentially means that protection is given to the way a product looks, and may result from a combination of elements such as shape, colour and material. The law does not require a design to be aesthetically pleasing in order to meet the requirements for registration, for guidance (see recital 10 of Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 (PDF, 150 KB)). Therefore a design can still be afforded protection even if it is considered to be ‘ugly’.

2.03

As set out in the RDA, it is possible to protect the appearance of the whole product, for example, the design of a kitchen table. However, it is also possible to protect just part of a product. Continuing with the table example, one can protect the design of a table leg without protecting per se the design of the whole table to which it is attached.

2.04

Section 1(2) lists colour as being a feature of design which can be protected. For example, a design can be filed either in pure black-and-white, in greyscale, or in colour. Where a design is filed in colour, the colouration will form part of the protection conferred; where a design is filed in greyscale, the tonal contrast may form part of the design. It should be noted that the Registrar does not consider single colours per se to fall under the definition of a design as set out in the RDA, and so applications seeking to protect colour per se will attract an objection. For more information on the effect and impact of colour used in design representations, please see paragraph 11.08 ‘Representations: Colours’.

2.05

It is also important that the applicant clearly states the nature of their design by completing the relevant section of the application form (that is the section entitled ‘About the design - What product is your design going to be used on or incorporated onto?’, where one should indicate the product to which the ornamentation is to be applied or to which it is to be incorporated).

2.06

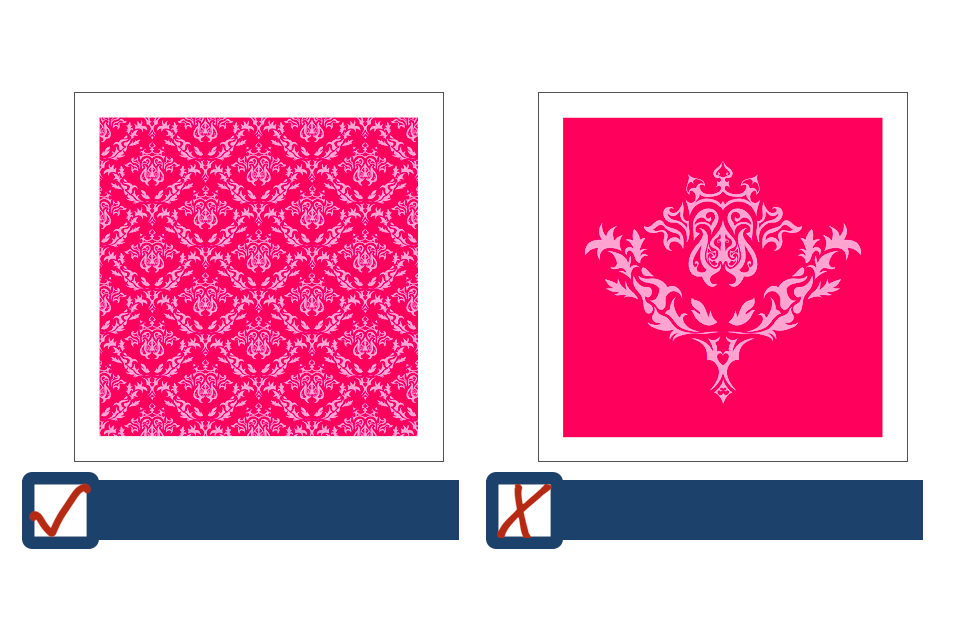

In line with Rule 4(7), where protection is required for a repeating surface pattern such as, for example, a pattern applied to wallpaper or textiles, the applicant must ensure that, as well as being described as such on the application form, the representations used present enough of the pattern to show that it can be infinitely repeated. Of the two representations shown below, the image on the left is an example of an acceptable repeating surface pattern. In contrast, the example on the right is a self-contained two-dimensional design. Although acceptable in its own right, it is not an example of a repeating surface pattern.

2.07

In relation to designs consisting of, or incorporating, so-called ‘complex products’:-

| Section 1(3) states: |

| (3) In this Act- “complex product” means a product which is composed of at least two replaceable component parts permitting disassembly and reassembly of the product; and “product” means any industrial or handicraft item other than a computer program; and, in particular, includes packaging, get-up, graphic symbols, typographic type-faces and parts intended to be assembled into a complex product. |

2.08

Designs consisting of complex products (a petrol lawnmower, for example) are acceptable as a whole. However, individual component parts which are non-visible in the course of normal use of the product cannot benefit from protection because they fail to meet the requirements of Section 1B(8) (see paragraphs 3.09 to 3.10).

2.09

Section 1(2) of the RDA only provides protection to designs for ‘products’ (or parts of products). Section 1(3) defines the term ‘product’ to mean ‘any industrial or handicraft item’ (a definition which is taken to include two-dimensional images and/or logos alongside three-dimensional shapes). To enjoy protection as a registered design, such an item must have either gone through an industrial process, or have been crafted in some way. It is clear, therefore, that any naturally occurring item such as a fruit, vegetables, person or animal will not conform to this definition, and so cannot be afforded protection. See, for example, the following (unacceptable) representation of a naturally-occurring fruit:

2.10

An objection will not be raised if information provided on the application form discloses that the object shown is artificial, meaning that, for example, the shape of an artificial fruit or vegetable could qualify for protection as a registered design.

2.11

As per the text of Section 1(3) RDA (presented at para 2.07 above), computer programs are specifically excluded from protection. However, this does not mean that the physical appearance and layout of certain forms of digital media cannot be protected as registered designs. For example, the visual appearance of computer icons and screen saver graphics, and the visual layout of software interfaces (often referred to as ‘Graphical User Interfaces’ or ‘GUIs’) and web pages are not precluded from protection per se. The appearance of such forms of digital content can be accepted for registration provided they meet all other requirements of the RDA.

2.12

By its inherent nature, the appearance of digital media can be both static (for example, web page and GUI layouts) and non-static (for example animated screensavers and ‘dynamic’ icons). In the case of the former, designs can be represented via the use of actual screenshots or line drawings showing the configuration of graphic elements visible within a web page, GUI or other form of digital platform. In the case of the latter, whilst it may be possible to protect the appearance of dynamic/animated digital content, applicants should be careful to ensure that the representations used accurately capture the design intended for protection. Further information on the capture of animated/dynamic designs is provided at paragraph 11.34.

2.13

The suitability for registration of an animated/dynamic design will always be considered according to the facts of each individual case. Applicants should also note that design protection corresponds to a product’s appearance only. Therefore, registering the visual characteristics of an animated/dynamic web page, graphical user interface, icon or other form of digital content will not protect any aspect of functionality

2.14

An application for a registered design protects the appearance of a product. Whilst section 1(2) RDA refers to a product, or a part of a product, in the singular, that does not preclude the registration of a product which consists of multiple components. A product that consists of multiple components can be considered as a product in its own right, and can be represented in a single design application, if the components together are considered to be a unitary product. This approach has been confirmed in the Appointed Person (AP) decision number BL O/374/21. However, in paragraphs 21 and 22 of that decision, the AP rejected the submission that any two, or more, unrelated items can be protected as part of a single design application. However, the AP went on to accept that a product need not always consist of just one physical object, for example, a canteen of cutlery may contain more than one item but still be considered a single design.

Factors which may be taken into consideration when assessing if a number of articles make up a single unitary product may be where the appearance or function are complementary to each other and they are, in normal circumstances, sold together as one single product. If the articles also stay together for the normal life of the product, this would be a further indicator that they comprise a single unitary product. Examples would include a chess set consisting of a board, pieces and a box, or a canteen of cutlery consisting of various knives, forks and spoons, which are specifically adapted to store and display its contents. However, where an element is removed and thrown away after use, for example, disposable gloves within its packaging or a food item removed from a box, in such cases an objection may be raised.

Equally, a bag which has both handles and a detachable body strap is considered a unitary product.

2.15

However, an objection will be raised against applications which contain multiple elements that are not considered to be a unitary product, for example, a physical product and the box in which it is contained at a point of sale. In decision BL O/374/21, the AP gave an example of when certain articles shown together would not be considered as a single product:

23. By contrast, eggs are very commonly sold in boxes of half a dozen. In my view it does not follow that 6 eggs, or an egg box together with the 6 eggs it contains, are to be regarded as a single product. This is simply a convenient number of eggs to handle, distribute and buy, and the eggs will be consumed one by one as needed and the box will then be thrown away.

The example given is clear that a product (albeit that eggs are a natural product and would not be accepted for registration under section 1(2) of the Act) and its packaging would not be considered a unitary product. This is consistent with the decision set out in BL O/260/18 in which the inter partes hearing officer stated, at paragraph 23:

“….no one would say that the cardboard box in which (say) a keyboard is sold is part of the product. It is just packaging for the product inside and will usually be thrown away (or hopefully recycled) once the keyboard has been unpacked. In these circumstances, the packaging and the keyboard cannot be regarded as a ‘unitary object’ (to borrow a term from the case law of the General Court in Ball Beverage Packaging Europe Ltd v EUIPO)”.

Therefore, the examples shown below would face an objection under section 1(2) RDA.

A further example, which would not be considered acceptable, would be a gift set consisting of different toiletries, for example a hand lotion, a perfume bottle and soap sold together in a basket, or gift box.

2.16

Amongst the twelve views permitted in respect of applications filed electronically (there is no limit to the number of representations allowed via the filing of a paper form), applicants must submit at least one view showing the set of articles in its entirety, as shown in the acceptable examples above, of the canteen of cutlery and chess set.

2.17

The Registrar will accept fonts and typefaces providing they are stylised. Plain written text will be refused under Section 1(2) RDA on the basis that it is not considered to be a product.

2.18

Concepts or ideas cannot be protected via design registration. Therefore, where an applicant seeks to register a design which is intended for alteration, adaptation, and/or customisation (for example, a personalised item such as an article of clothing intended to carry the name of the wearer) but does not intend for the protection conferred to be limited to any one particular form, the examiner will, prior to registration, inform the applicant that protection is given only to the design as shown.

3.01

Section 1B of RDA sets out the requirements for assessing novelty and individual character:-

| Section 1B states: |

| (1) A design shall be protected by a right in a registered design to the extent that the design is new and has individual character. (2) A design is new if no identical design or no design whose features differ only in immaterial details has been made available to the public before the relevant date. |

3.02

It should be noted that whilst the RDA confirms that a design’s validity is dependent upon its novelty, a ‘novelty search’ for the purposes of identifying prior designs is not conducted as part of the examination process. This means that on receipt of a design application, the examiner will not undertake a search for prior designs, and will therefore set aside any consideration of a refusal based on grounds of novelty or individual character.

3.03

Because novelty and individual character are a requirement for protection, the applicant has a responsibility to consider and identify such characteristics in a design before seeking to register it. The absence of an examination-stage novelty search means that some designs which do not meet the requirements for registration may still be listed in the Designs Register. However, any registered design can be challenged by one or more third parties alleging that it is not new and/or lacks individual character. Such a challenge can be launched through either the IPO’s Trade Marks & Designs Tribunal or through the Courts, which may then result in the design being declared invalid.

3.04

If an applicant is in any doubt about the validity of a design, they can ask the Registrar to carry out a search of designs already registered in the UK. The search can only be requested via submission of a Form DF21, which must be accompanied by a copy of the design to be searched, and a written indication of the type of product to which the design relates. It should be noted that where such a request is made, the examiner will only carry out a search of the UK and Hague registers.

3.05

Section 1B(3) of the RDA sets out the criteria for assessing individual character:-

| Section 1B(3) states: |

| For the purposes of subsection (1) above, a design has individual character if the overall impression it produces on the informed user differs from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design which has been made available to the public before the relevant date. |

3.06

The identity of the so-called ‘informed user’ has previously been assessed by the Courts. In Case T-9/07 Grupo Promer Mon Graphic SA v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market [2010] ECR II-0000, the General Court of the European Union held, at paragraph 62, that:

the informed user is neither a manufacturer nor a seller of the product in which the designs at issue are intended to be incorporated or to which they are intended to be applied. The informed user is particularly observant and has some awareness of the state of the prior art, that is to say the previous design relating to the product in question that had been disclosed on the date of filing of the contested design, or, as the case may be, on the date of priority claimed.

3.07

The relevant date is the date that the application is made, or is treated as having been made (section 1B (7) RDA refers).

3.08

There is a twelve month grace period before the relevant date, during which time the designer can disclose their design without it being open to invalidation on the grounds of lack of novelty (Section 1B(6)(c) RDA refers).

3.09

Sections 1B(8) and (9) of the RDA sets out the novelty requirements of component parts of a complex product:-

| Section 1B(8) and (9) states: |

| (8) For the purposes of this section, a design applied to or incorporated in a product which constitutes a component part of a complex product shall only be considered to be new and to have individual character- (a) If the component part, once it has been incorporated into the complex product, remains visible during normal use of the complex product; and (b) To the extent that those visible features of the component part are in themselves new and have individual character. (9) In subsection (8) above “normal use” means use by the end user; but does not include any maintenance, servicing or repair work in relation to the product. |

3.10

The examination procedure does not include any consideration of this section of the RDA, meaning that an examiner will not assess the likelihood of a component part being visible during the normal course of use and will not raise an objection under these grounds. The implications, however, remain the same as those for novelty and individual character - being that a third party can apply to invalidate the design based on the provision.

4.01

Section 1C of the RDA prohibits the protection of certain types of technical designs. The provision is split into three sections as explained below, and the examination of a design will assess suitability and compliance in respect of all three (Designs Practice Notice 05/03 refers).

4.02

This provision is not intended to exclude from protection those designs which possess no aesthetic quality, but instead seeks to avoid hampering technological innovation. A technological design may, in fact, be more suited to the protection afforded by a patent as opposed to a registered design.

4.03

The word ‘solely’ plays a significant role in the examiner’s consideration as to whether a design application is acceptable under this provision. Advocate General Ruiz-Jarabo Colomer gave some guidance as to how Section 1C(1) should be interpreted in relation to designs in [Philips Electronics NV v Remington Consumer Products Limited C-299/99 where, at paragraph 34, he stated that:

the level of functionality must be greater in order to be able to assess the ground for refusal in the context of designs; the feature concerned must not only be necessary but essential in order to achieve a particular technical result: form follows function…

The subject of 1C(1) has also been looked at in Doceram GmbH v CeramTec GmbH (C-395/16). In reaching its decision the CJEU considered the wording of Article 8(1) of the regulation (equivalent to S.1C(1) of the RDA), and found in paragraph 22:

…it must be held that in the absence of any definition of that expression that regulation does not lay down any criteria for determining whether the relevant features of appearance of a product are solely dictated by its technical function. Therefore, it does not follow from that article or any other provision of that regulation that the existence of alternative designs (multiplicity of forms theory) which fulfil the same technical function as that of the product concerned is the only criterion for determining the application of that article.

The CJEU in Doceram ruled that:

Article 8(1) of Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs must be interpreted as meaning that in order to determine whether the features of appearance of a product are exclusively dictated by its technical function, it must be established that the technical function is the only factor which determined those features, the existence of alternative designs not being decisive in that regard…

4.04

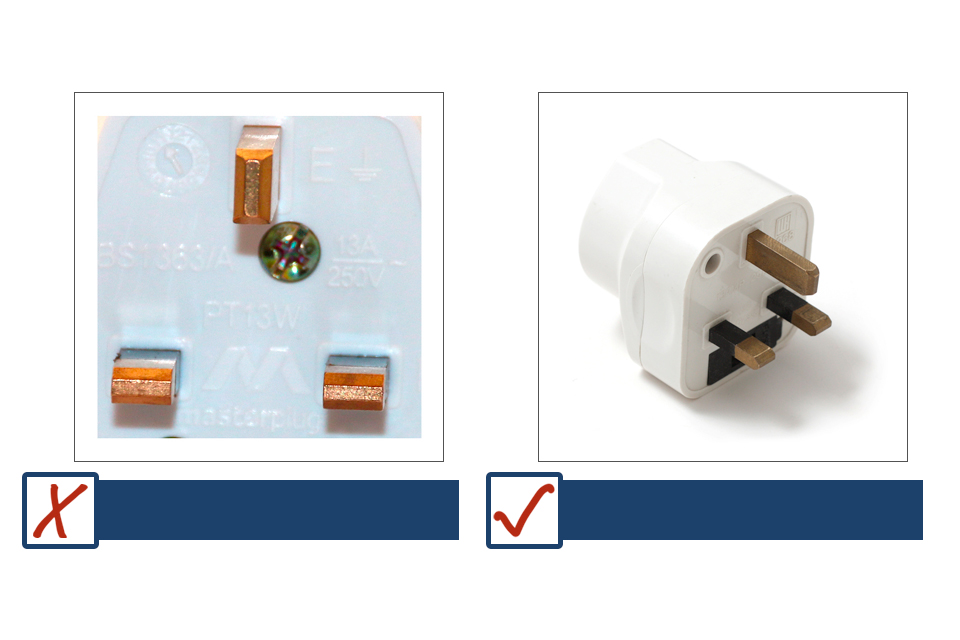

Therefore, if a designer has some degree of choice or ‘design freedom’ in creating their design, it should be considered eligible for protection. In the case of the design of an electrical plug, it should be noted that the prongs of the plug would not themselves be protectable as they fail to comply with Section 1C(1). This is because they are designed in such a way as to perform a technical function, that is to distribute electricity by connecting the plug to the socket and electrical mains. However, the plug as a whole is acceptable as long as there is design freedom in the plug casing. Illustrating this point, the example on the left would attract an objection under Section 1C(1), whilst the example on the right would be accepted for registration:

4.05

The fact that the technical result may be achievable by another means will not necessarily render a design acceptable for registration. If all of the features are dictated by technical function and it appears to the examiner that the designer had no design freedom (or, at best, only negligible levels of design freedom), then an objection under Section 1C(1) will still be taken.

4.06

An applicant may successfully overcome a Section 1C(1) objection if they are able to demonstrate that there is sufficient design freedom in the product, and that it therefore need not appear to the exact form as shown in the application. In such cases, the onus will be on the applicant to prove that the design is acceptable for registration, not on the examiner to prove it is unacceptable.

4.07

Section 1C(2) RDA is referred to as the ‘must-fit’ provision:-

| Section 1C(2) states: |

| A right in a registered design shall not subsist in features of appearance of a product which must necessarily be reproduced in their exact form and dimensions so as to permit the product in which the design is incorporated or to which it is applied to be mechanically connected to, or placed in, around or against, another product so that either product may perform its function. |

4.08

This section of the Act prohibits the registration of those designs which have been created merely for the purposes of fitting to another product so that the resulting item can fulfil its intended function. By their very nature, such designs will have little to no design freedom, meaning that the designer will have a limited scope when determining the product’s overall appearance. To place into context, it is helpful to think of this provision as being a means for preventing the protection of what are informally referred to as ‘must fit’ features see paragraph 27 of Dyson Ltd v Qualtex (UK) Ltd [2006] RPC 31.

4.09

Given the limited design freedom in relation to ‘must fit’ parts, the examiner must determine whether there is any part of the design which is not required in order for it to perform its function. Where a degree of design freedom is identified, however limited, then the application will be acceptable. For example, a generic car spotlight design will avoid being caught by the ‘must fit’ provisions where the representation submitted confirms that it is suitable for fitting to any make or model of vehicle.

4.10

However, if the examiner cannot identify any aspect of the design which is not necessary in order to perform the desired technical function, then the application will be subject to an objection. For example, a car body panel requiring reproduction to an exact form and dimension in order to enable connection to its corresponding vehicle (and thereby perform its function) would be subject to an objection under s.1C(2).

4.11

It should be noted that if a part is considered acceptable under Section 1C of the RDA, it does not automatically follow that it will pass the requirements of Section 1B (8). The design may be open to invalidation if it is found that the product in question refers to a component part of a complex product which is not seen in normal use (an oil filter, for example).

4.12

Section 1C(3) of the RDA relates to the protection of the multiple assembly or connections of mutually interchangeable parts:-

| Section 1C(3) states: |

| Subsection (2) above does not prevent a right in a registered design subsisting in a design serving the purpose of allowing multiple assembly or connection of mutually interchangeable products within a modular system. |

This provision makes it clear that modular products should be differentiated from standalone products by being afforded design protection, and is supported by Recital 15 of the European Directive 98/71/EC which reads:

Whereas the mechanical fittings of modular products may nevertheless constitute an important element of the innovative characteristics of modular products and present a major marketing asset and therefore should be eligible for protection.

4.13

Section 1C(3) of the Act ensures that Section 1C(2) does not prevent protection being afforded to those features which allow the interconnection of items. So, for example, concert-venue seating will commonly have an interlocking feature which allows the seats to fit together and be dissembled for storage. Such a feature would not fail to meet the requirements of Section 1C(2) notwithstanding the fact that the shape and dimensions etc. would need to be exactly reproduced in order for one such item to fit to another.

5.01

Section 1D of the RDA sets out the legislation relating to public policy and morality:-

| Section 1D states: |

| A right in a registered design shall not subsist in a design which is contrary to public policy or to accepted principles of morality. |

5.02

When assessing an application under Section 1D, the examiner will consider whether a design falls within the accepted parameters of public policy and/or morality. The term ‘public policy’ applies to those designs which are likely to induce public disorder, or increase the likelihood of criminal or other offensive behaviour. Caution will always be exercised where designs appear to have criminal connotations, for example, where they are associated with inter alia counterfeiting, illegal drugs or violence, where they exhibit racial, religious or discriminatory characteristics, or where they appear to trivialise criminal activity. Examiners must decide whether such designs should benefit from, or be denied, the advantages of protection conferred by registration. In the context of Section 1D, it is useful to refer to comments made by Geoffrey Hobbs QC, sitting as the Appointed Person in the Jesus case (BL-O-021-05(PDF,47.3 KB)). Although Mr Hobbs was addressing the equivalent provision in trade mark law, his comments are equally applicable to designs:

The right to freedom of expression must always be taken into account without discrimination under section 3(3)(a) and any real doubt as to the applicability of the objection must be resolved by upholding the right to freedom of expression, hence acceptability for registration.

5.03

Reflecting the reasonable and liberal approach as described by Mr Hobbs QC above, it is rare for the Registrar to raise an objection on public policy grounds. Nevertheless, examiners should take care, especially where a design appears to relate to an unlawful act (for example, a tee-shirt with a logo and/or phrase which explicitly promotes the use of illegal substances). Other areas to note include designs which contain racist messages and/or make detrimental references as to a person’s sexual orientation. Such designs would be likely to invoke upset and anger amongst a significant majority of the public, and so would be subject to an objection under Section 1D.

5.04

When assessing a design’s suitability for acceptance and registration under this provision, the examiner must take into account the public perception at the time of filing. The possibility of a design being viewed as offensive by some elements of society is not a sufficient basis for raising an objection under Section 1D (for this reason, and by way of example, a design which presents mild sexual connotations is likely to be acceptable). In relation to the Registrar’s role in determining where exactly the line sits between a design which is likely to result in mere distaste and one which is likely to invoke an objection under Section 1D, the Courts have stated the following in the HALLELUJAH trade mark decision ([1976] RPC 605) at paragraph 1 of page 608:

(The Registrar) must certainly not act as a sensor or arbiter of morals, nor yet as a trendsetter. He must not lag so far behind the climate of the time that he appears to be out of touch with reality, but he must at the same time not be so insensitive to public opinion that he accepts for registration a mark which many people would consider offensive.

5.05

The Courts have provided further guidance in Masterman ([1991] RPC 89) where, in respect of the design of a small toy displaying male genitalia, Mr Justice Aldous stated the following:

Each design has to be considered individually and in the context of what reasonable use would be made of it, and it must be judged against the background of public opinion at the date of application. It is also necessary to consider the attitudes of Parliament as reflected by legislation and also weigh up any conflicting opinions that various sections of the public may have. For instance, the design for which registration is sought would be thought by many members of the public to be a clever and humorous design, giving no offence, whereas others might find it a distasteful joke. The extent of that latter view must be weighed against the legitimate views of others and a decision reached as to whether there are real grounds for preventing the designer from having the proprietary right given by the Act to protect his work.

5.06

Mr Justice Aldous concluded that evidence of mere distaste amongst a section of the public is not a valid reason to refuse registration. However, as with all design applications, each case will be assessed on its own merits.

5.07

Unauthorised use of the Red Cross and related symbols, by anyone and in any manner, is expressly restricted by the Geneva Convention Act 1957. As a consequence, the registration of any such symbol (or corresponding word/name) is contrary to public policy under Section 1D of the Registered Designs Act. Examples of symbols protected under the Geneva Convention are shown below:

5.08

Objections under Section 1D will also be taken against applications containing the terms ‘Red Cross’, ‘Geneva Cross’, ‘Red Crescent’ and/or ‘Red Lion and Sun’ and ‘Red Crystal’. Imitations of the symbols or phonetic equivalents of the words (such as, for example, ‘Redd Kross’, ‘Red Kresent’, ‘Red Lyon and Son’ and ‘Red Krystal’) and/or figurative combinations of words and symbols (such as ‘Red +’ and ‘Red X’), would also face objection.

5.09

Given the special significance of these symbols, use of the above within the UK must be authorised. Where the design contains or consists of an exact replica of the protected signs with no other matter, consent must be sought from the Ministry of Defence. If the design contains or consists of a sign similar to a protected sign, or is applied for together with other matter, then consent must be sought from the Secretary of State, via the Intellectual Property Office. In both of these cases the MoD or the Secretary of State will also consult with the Special Counsel, International Law of the British Red Cross before any consent may be given.

5.10

From 12 December 2017, it is an offence to use the cultural emblem or a design that so nearly resembles it that it could be mistaken for it, otherwise than as authorised by the Cultural Property (Armed Conflicts) Act 2017. The 1954 Hague Convention establishes the cultural emblem (known as ‘the blue shield’) as the distinctive emblem to be used to identify cultural property which is protected by the Convention and its Protocols. The emblem is also used to identify protected transport of cultural property and to identify designated individuals with responsibilities relating to the protection of cultural property during armed conflicts.

If an application is received for a design which includes a representation of the emblem, or a design which so nearly resembles it that it could be mistaken for it, an objection will be raised under section 1(D).

6.01

Section 1(1) of Schedule A1 of the RDA sets out the grounds for refusal for designs containing certain emblems:-

| Section 1 (1) of Schedule A1 states: |

| (1) 1 A design shall be refused registration under this Act if it involves the use of- (a) The Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it; (b) A representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags; (c) A representation of Her Majesty or any member of the Royal family, or any colourable imitation thereof; (d) Words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation unless it appears to the registrar that consent for such use has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or (as the case may be) the relevant member of the Royal Family. |

Note

Section 10 of the Interpretation Act 1978 states:

10 References to the Sovereign

In any Act a reference to the Sovereign reigning at the time of the passing of the Act is to be construed, unless the contrary intention appears, as a reference to the Sovereign for the time being. In view of the above, any reference to Her Majesty in the RDA, will be construed as a reference to His Majesty and therefore any objection under S.1(1) of Schedule A1 of the RDA will make reference to His Majesty.

6.02

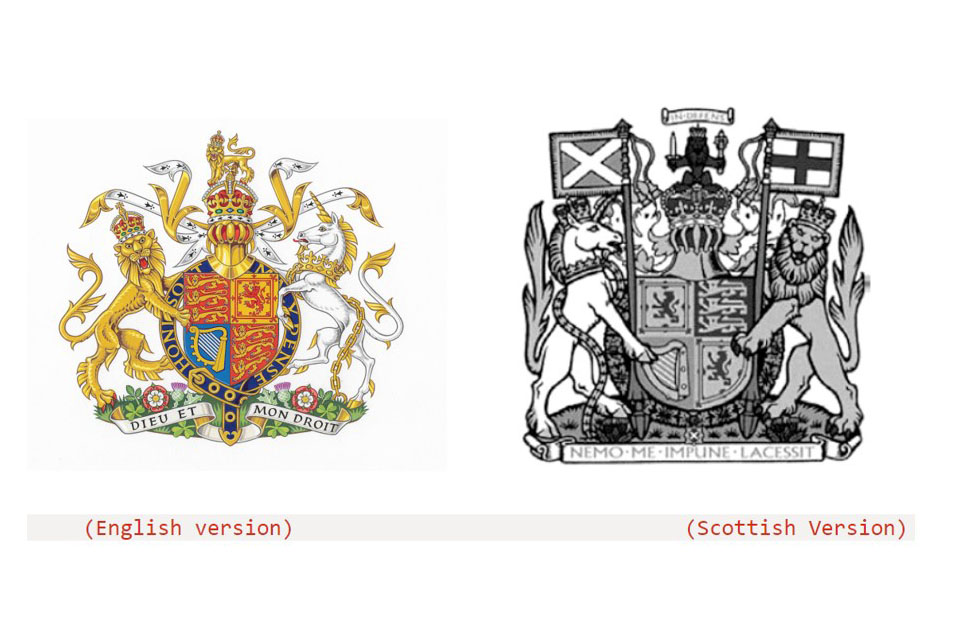

An objection shall be raised where an application consists of, or contains, a representation of Royal arms, or where a design contains something which is very similar to such arms. Two ‘conventional’ representations of Royal Arms are shown below:

6.03

The prohibition also covers the ‘principal armorial bearings’ of the Royal Arms. This is considered to mean the shield, motto, supporters and crest, both individually and separately. For example, a design containing a unicorn supporter with other distinctive elements which have no royal connection, would be open to an objection under Schedule A1. However, minor elements within the principal armorial bearings, for example the Tudor rose on the base, would not be considered to consist of ‘principle armorial bearings’ for the purposes of the Act.

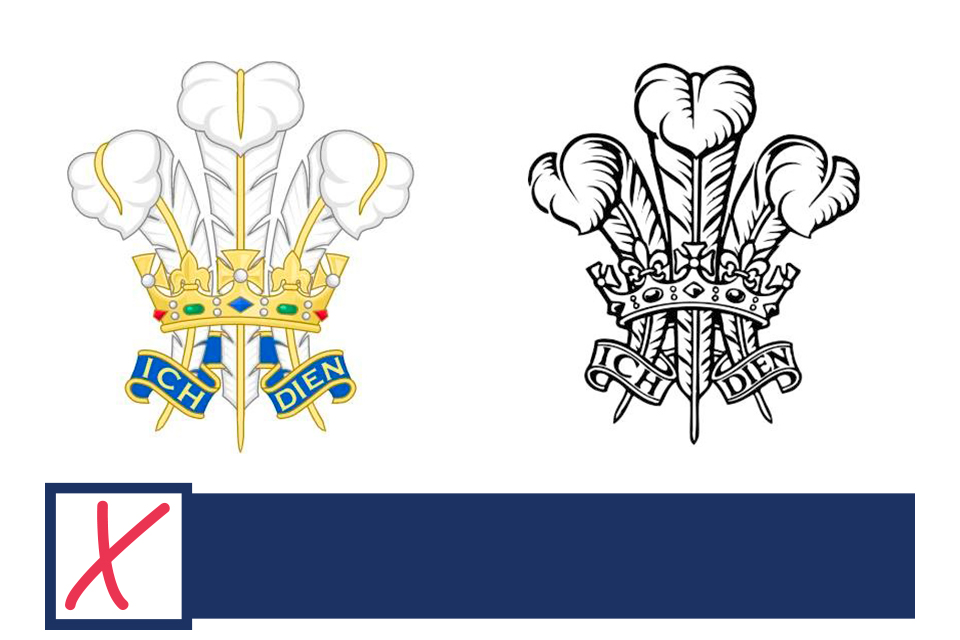

Some elements of Royal Arms are protected as separate elements in their own right, for example the three lions and the harp. Similarly, The Prince of Wales’ Three Ostrich Feather Badge and authorised versions of the badge are also protected under Schedule A1. Conventional representations of The Prince of Wales’ Three Ostrich Feather Badge are:

6.04

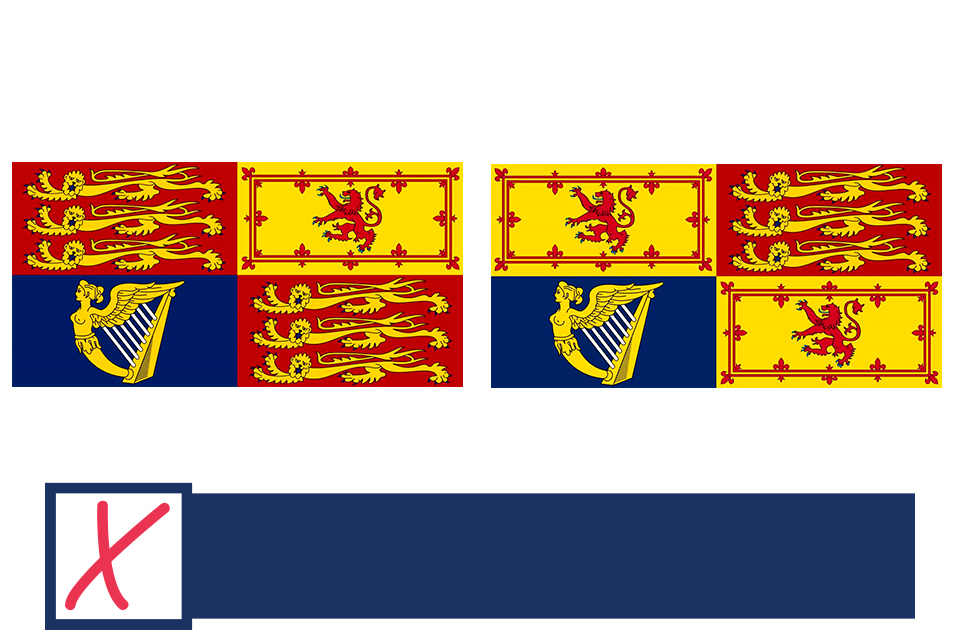

If a design includes a representation of one of the Royal Flags an objection is appropriate under Schedule A1.

Conventional representations of the Royal Flags are shown below:

6.05

Images of the Royal crown, Royal Coronets, and Royal flags will also be subject to an objection on the same grounds. Examples of Royal Crowns and Coronets are presented below:

6.06

In respect of those illustrations of crowns and coronets which will not attract an objection under Schedule A1 RDA, the Royal Warrant Holders Association has already advised the Registrar that crowns similar to those shown below may be used for business purposes without infringement of the Royal Crown:

6.07

Any design which contains an image of His Majesty the King, or any member of the Royal family, (such as, for example, a tea towel design intended for sale as a London souvenir) will be open to objection under Section 1(1) of Schedule A1

6.08

In relation to personal names and titles, the Lord Chamberlain’s Office has provided the Registrar with the following list of Royal Family members. Examiners will consult this list when determining whether or not an objection under Schedule A1 should be raised. Examiners will also be aware of the need to check any subsidiary titles in addition to the titles shown below, to consider whether or not an objection under Schedule A1 is relevant:

| The King |

| The Queen |

| The Prince and Princess of Wales |

| Prince George of Wales |

| Princess Charlotte of Wales |

| Prince Louis of Wales |

| The Duke and Duchess of Sussex |

| Prince Archie of Sussex |

| Princess Lilibet of Sussex |

| The Duke of York |

| Princess Beatrice, Mrs. Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi and Mr. Edoardo Mapelli |

| Miss Sienna Mapelli Mozzi |

| Princess Eugenie, Mrs. Jack Brooksbank and Mr. Jack Brooksbank |

| Master August Brooksbank |

| Master Ernest Brooksbank |

| The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh |

| Earl of Wessex |

| The Lady Louise Mountbatten-Windsor |

| The Princess Royal and Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence |

| Mr. Peter Phillips |

| Miss Savannah Phillips |

| Miss Isla Phillips |

| Mr. and Mrs. Michael Tindall |

| Miss Mia Tindall |

| Miss Lena Tindall |

| Master Lucas Tindall |

| The Earl of Snowdon |

| Viscount Linley |

| The Lady Margarita Armstrong-Jones |

| The Lady Sarah Chatto and Mr. Daniel Chatto |

| Mr. Samuel Chatto |

| Mr. Arthur Chatto |

| The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester |

| The Duke and Duchess of Kent |

| Prince and Princess Michael of Kent |

| Princess Alexandra, the Honourable Lady Ogilvy |

| Sarah, Duchess of York |

6.09

The names and pictorial illustrations of Royal places of residence will be subject to an initial objection under Schedule A1 only where they are presented in such a way as to lead the public into expecting that their use has been approved via official Royal patronage and/or authorisation. Where such an objection is raised, it may be overcome by the applicant through obtaining (and providing the Registrar with proof of) consent to use from His Majesty the King, or the relevant member of the Royal family. In the first instance, approaches for consent should be directed towards the Lord Chamberlain’s office, at Buckingham Palace, London, SW1A 1AA.

6.10

The Registrar holds a list of Royal Residences as supplied by the Lord Chamberlain which, like the list of Royal Family members, will be used by Examiners in the context of Schedule A1. Although not an exhaustive list, the following are all recognised as being official Royal residences:

| Buckingham Palace, London |

| Clarence House, London |

| Kensington Palace, London |

| Wren House, Kensington Palace, London |

| St. James’s Palace, London |

| Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire |

| Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh |

| Hillsborough Castle, County Down, Northern Ireland |

| The Royal Lodge, Windsor, Berkshire |

| Bagshot Park, Surrey |

| Thatched House Lodge, Richmond, |

| Barnwell Manor, Barnwell, |

| Northamptonshire Gatcombe Park, Minchinhampton, Gloucestershire |

| Sandringham House, Norfolk |

| Balmoral Castle, Aberdeenshire |

| Craigowan Lodge, Balmoral, Aberdeenshire |

| Delnadamph Lodge, Balmoral, Aberdeenshire |

| Birkhall House, Balmoral, Aberdeenshire |

| Highgrove House, Gloucestershire |

| Llwynywormwood, Myddfai, Llandovery, Carmarthenshire |

| Tamarisk, Isles of Scilly |

| Castle of Mey, Thurso, Caithness |

6.11

Designs which suggest Royal patronage may include a pictorial representation of a Royal residence or an indication of a Royal Warrant, i.e. the portcullis and crown as shown below:

6.12

In all cases, an objection raised under section 1 (1) can be overcome if the applicant can demonstrate that consent has been given by, or on behalf of, His Majesty or (as the case may be) the relevant member of the Royal family. Such consent must be presented to the Registrar, in writing, before any objection is waived.

6.13

Section 1(2) of Schedule A1 of the RDA sets out the grounds for refusing designs containing national flags:-

| Section 1(2) of Schedule A1 states: |

| (2) A design shall be refused registration under this Act if it involves the use of- (a) The national flag of the United Kingdom (commonly known as the Union Jack); or (b) The flag of England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland or the Isle of Man, and it appears to the registrar that the use would be misleading or grossly offensive. |

6.14

Composite designs which contain representations of the UK national flag, the St George Cross, the Welsh Flag and the Scottish Saltire etc. (in combination with other elements) must be considered in their totality and will most likely to be considered acceptable. An objection will be appropriate only if, by virtue of the presence of a national flag contained within it, the design is deemed misleading or grossly offensive.

6.15

A design incorporating one of the UK national flags will be misleading if it suggests, implies or explicitly indicates that products to which the design is incorporated are made in the UK when they are not. However, unlike trade mark law, the protection conferred onto a registered design is not bound by law to any specific product - a factor which makes it difficult for an examiner to make a judgement as to whether a design could be considered misleading. It therefore follows that most applications containing national flags will not be subject to an objection under this provision. However, each case will be considered on its own merits, and an objection will be taken if the examiner identifies a genuine capacity for deception.

6.16

In terms of offensiveness, a design containing, for example, a Union Flag accompanied by a racist slogan, may be subject to objection under Section 1(2) of Schedule A1 (as well as section 1 D - paragraphs 5.02 to 5.06 refer.

6.17

Section 1(3) of Schedule A1 of the RDA sets out the grounds under which designs containing certain arms and insignia can be refused:-

| Section 1(3) of Schedule A1 states: |

| (3) A design shall be refused registration under this Act if it involves the use of- (a) Arms to which a person is entitled by virtue of a grant of arms by the Crown; or (b) Insignia so nearly resembling such arms as to be likely to be mistaken for them: unless it appears to the registrar that consent for such use has been given by or on behalf of the person concerned and the use is not in any way contrary to the law of arms. |

6.18

Therefore, an objection shall be raised wherever a design consists of, or contains, an armorial bearing, heraldic device, or a coat of arms which is protected in the UK.

The onus is firmly on the registrar to refuse any design application which includes elements listed in Section 1(3) Schedule A1 (and which has not been supported by evidence of consent from the appropriate person). In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the right to grant arms lies with the present-day Officers of the College of Arms (under the Garter King) and can be granted to individuals and corporate and public bodies amongst others. The right to bear arms is granted indefinitely.

6.19

The legal regime in Scotland differs from that of the rest of the UK. In Scotland, the Lord Lyon advises that arms, as protected by Scottish law, are regarded as incorporeal heritage or property and are rights in rem maintainable against anyone within Scotland. Therefore, it appears that the use of arms in Scotland by a person whose right is not on record in the statutory Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland constitutes a statutory offence, and offenders may be prosecuted at the instance of the Procurator Fiscal of Lyon Court.

6.20

Where a design application consists of, or contains, a heraldic device, and so may be affected by the laws of Arms in Scotland and England, the applicant will need to contact the Lord Lyon (in Scotland) and Garter King (in England) to obtain guidance as to the registrability of the design. Following guidance from either of the aforementioned, the Registrar may waive any objection raised.

6.21

Where the design is found to consist of, or contain, what appear to be arms, or insignia which resemble arms, the following text will be included in the Examination Report:

Your design appears to [consist of/contain] arms, and may therefore be found to be objectionable under Schedule A1 of the Registered Designs Act 1949. The right to bear arms falls under the jurisdiction of the Kings of Arms for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the Lord Lyon in Scotland, who you will need to contact for a decision as to whether or not your application can be accepted. Once we have received confirmation from the Garter King of Arms and Lord Lyon that your design is acceptable, we will forward it to registration. However, if it appears that the design is not acceptable we will notify you accordingly.

For further information on these matters you may contact the following:

Garter King of Arms

The College of Arms

Queen Victoria Street

London

EC4V 4BT

www.college-of-arms.gov.uk

The Court of the Lord Lyon

HM New Register House

Edinburgh

EH1 3YT

www.lyon-court.com

6.22

Section 1(4) of Schedule A1 of the RDA sets out the grounds under which designs containing the Olympic Symbols will be refused:-

| Section 1 (4) of Schedule A1 states: |

| (4) A design shall be refused registration under this Act if it involves the use of a controlled representation within the meaning of the Olympic Symbol etc (Protection) Act 1995 unless it appears to the registrar that- (a) The application is made by the person for the time being appointed under section 1(2) of the Olympic Symbol etc (Protection) Act 1995 (power of Secretary of State to appoint a person as the proprietor of the Olympics association right); or (b) Consent for such use has been given by or on behalf of the person mentioned in paragraph (a) above. |

6.23

Under the provision, an objection shall be taken against any design containing the Olympic and/or Paralympic symbols shown below:

6.24

The Olympic motto (‘Citius, Altius, Fortius’ which means ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’), the Paralympic motto (‘Spirit in Motion’), and the words ‘Olympic(s)’, ‘Paralympic(s)’, ‘Olympian(s)’, ‘Paralympian(s)’, ‘Olympiad(s)’ and ‘Paralympiad(s)’ are also all protected under the Olympic Symbol etc (Protection) Act 1995 (as amended by the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Act 2006), as are those signs deemed sufficiently similar to the Olympic/Paralympic Symbol, the Olympic/ Paralympic motto and the words ‘Olympic(s)’, ‘Paralympic(s)’, ‘Olympian(s)’, ‘Paralympian(s)’, ‘Olympiad(s)’ and ‘Paralympiad(s)’ to the extent that they are likely to create an association with those protected signs in the mind of the public. Where an application is made consisting of, or containing, any of the aforementioned Olympic/Paralympic symbols or words (or those which are deemed to be similar in accordance with the law), examiners will object under Section 1(4) of Schedule A1 of the RDA.

6.25

Section 2 of the Schedule A1 of the RDA sets out the grounds under which designs containing the flags of Paris Convention countries will be refused:-

| Section 2 of Schedule A1 states: |

| (1) A design shall be refused registration under this Act if it involves the use of the flag of a Paris Convention country unless- (a) The authorisation of the competent authorities of that country has been given for the registration; or (b) It appears to the registrar that the use of the flag in the manner proposed is permitted without such authorisation. (2) A design shall be refused registration under this Act if it involves the use of the armorial bearings or any other state emblem of a Paris Convention country which is protected under the Paris Convention unless the authorisation of the competent authorities of that country has been given for the registration. (3) A design shall be refused registration under this Act if- (a) The design involves the use of an official sign or hallmark adopted by a Paris Convention country and indicating control and warranty; (b) The sign or hallmark is protected under the Paris Convention; and (c) The design could be applied to or incorporated in goods of the same, or a similar, kind as those in relation to which the sign or hallmark indicates control and warranty; unless the authorisation of the competent authorities of that country has been given for the registration. (4) The provisions of this paragraph as to national flags and other state emblems, and official signs or hallmarks, apply equally to anything which from a heraldic point of view imitates any such flag or other emblem, or sign or hallmark. (5) Nothing in this paragraph prevents the registration of a design on the application of a national of a country who is authorised to make use of a state emblem, or official sign or hallmark, of that country, notwithstanding that it is similar to that of another country. |

6.26

An objection under Section 2, Schedule A1 will be taken wherever a design consists of, or contains, an unmodified representation of the national flag of a Paris Convention country. Such flags are afforded automatic protection without any requirement of notification to the World Intellectual Property Organisation (‘WIPO’), and without any need for them to be listed in WIPO’s Article 6ter database. A list of those countries which are signatories to the Paris Convention, and the Article 6ter database are available.

6.27

Sections 2.2 and 2.3 of Schedule A1 address the protected status given to those armorial bearings, other state emblems, official signs, and hallmarks which have been notified to WIPO and which are included in the Article 6ter database of protected armorial bearings, flags and other State emblems. Unlike national flags, it should be noted that armorial bearings, other State emblems and ‘other’ flags (that is those which are not national flags) will only be open to objection in instances where they have been previously notified to WIPO.

6.28

Section 2.4 of Schedule A1 addresses imitations of flags, emblems, signs and hallmarks, and confirms that where the imitation so closely resembles the original protected emblem, an objection must be raised. The following are contrasting examples of designs which would be considered both acceptable and unacceptable under this provision. The first example is a reproduction of the Flag of the United States of America - a design which is clearly objectionable under Section 2(1). In contrast, the second example borrows elements and has an overall configuration which might bring the US flag to mind, but is not intended to be a replica or imitation. As a result, it would be deemed acceptable under Sections 2(1) and 2(4):

6.29

The same logic applies to the following two examples. The first example contains a reproduction of the ‘Maple Leaf’ emblem as found in the Canadian flag, and may therefore attract an objection. In contrast, the second example is also a maple leaf, but is presented in more naturalistic style, and is clearly not intended to be an imitation of the Canadian national emblem.

6.30

Authentic representations of protected national emblems will face objection regardless of the presence of additional elements. In the following examples, which relate to two different reproductions of the Irish Shamrock (an emblem which is protected under Article 6ter), the public is unlikely to perceive any difference between the two versions shown. In the first example, the design consists solely of a shamrock, and so will attract an objection on account of that particular emblem’s protection granted under 6ter. In the second example, one is likely to perceive both the phrase ‘My Lucky Star’ and the shamrock device, with the word element doing little to lessen the impact or presence of the figurative shamrock element. As a result, an objection is as valid against the composite design as it is against the design consisting solely of a protected emblem. Both of the following examples would therefore attract an objection under Section 2, Schedule A1 RDA:

6.31

In all of the above scenarios, the objections taken may be overcome by obtaining consent from the relevant authorities (that is the national Governments responsible for protecting each emblem under Article 6ter).

6.32

Sections 3(1) and 3(2) of Schedule A1 of the RDA set out the grounds under which designs containing the armorial bearings, flags, emblems and names of international organisations can be refused:-

| Sections 3 (1) and 3 (2) of Schedule A1 state: |

| (1) This paragraph applies to- (a) the armorial bearings, flags or other emblems; and (b) the abbreviation and names, of international intergovernmental organisations of which one or more Paris Convention countries are members (2) A design shall be refused registration under this Act if it involves the use of any such emblem, abbreviation or name which is protected under the Paris Convention unless- (a) The authorisation of the international organisation concerned has been given for the registration; or (b) It appears to the registrar that the use of the emblem, abbreviation or name in the manner proposed- (i) Is not such as to suggest to the public that a connection exists between the organisation and the design; or (ii) Is not likely to mislead the public as to the existence of a connection between the user and the organisation. |

6.33

An objection will be raised if a design consists of, or contains, an emblem, abbreviation or name of a recognised international intergovernmental organisation which is also protected under Article 6ter as a result of it having been notified to WIPO. Two such examples are the flag of the Council of Europe and the symbol of the International Civil Defence Organisation, as shown below:

6.34

Unlike old design law, which only afforded protection to designs which were applied to a specific article of manufacture, design protection is no longer limited to a specific product. As a result, a broad (so-called ‘blanket’) objection will be taken in any and all cases where a national flag, emblem, armorial bearing, or emblem of an international organisation appears within a design. The applicant may be able to overcome such an objection by providing information on how the design is to be used, but each case will be considered on its own merits. If consent is obtained from the relevant body, then the objection will be waived.

6.35

As is the case with designs which incorporate elements deemed to imitate national flags, an objection will be raised against any design consisting of, or containing, elements found to be imitations of protected symbols of international intergovernmental organisations.